Abstract

In recent years, great progress has been made in the field of new therapeutic options for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The new direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) represent a great hope for millions of chronically infected individuals because their use may lead to excellent cure rates with fewer side effects. In Latin America, the high prevalence of HCV genotype 1 infection and the significant association of Native American ancestry with risk predictive single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in IFNL4 and ITPA genes highlight the need to implement new treatment regimens in these populations. However, the universal accessibility to DAAs is still not a reality in the region as their high cost is one of the major, although not the only, limiting factors for their broad implementation. Therefore, under these circumstances, could the assessment of host genetic markers be a useful tool to prioritize DAA treatment until global access to these new drugs can be achieved? This review will summarize the scientific evidences and the potential implications of HCV pharmacogenomics in this rapidly evolving era of anti-HCV drug development.

Introduction

The combination of pegylated IFN-alpha plus ribavirin (PEG-IFN/RBV) has been the standard of care for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection since late last century. The ultimate goal of this dual therapy is to eradicate HCV infection and thereby reduce the risk of progression to HCV-related liver complications. The endpoint of HCV treatment is to achieve a sustained virologic response (SVR), which has been strongly associated with viral clearance and effectively a cure.Citation1

In addition to its limited efficacy with the most prevalent HCV genotype worldwide, the PEG-IFN/RBV combination therapy frequently produces intolerability and substantial adverse effects. Consequently, the assessment of several viral (genotypes, viral load, mutations, etc.) and host (age, gender, degree of liver fibrosis, and alcohol consumption, etc.) factors were promptly incorporated in the treatment decision making in order to satisfy the urgent need of prediction of the PEG-IFN/RBV outcome. However, despite these influencing determinants, the existence of ethnic variability and individual differences observed in the clinical setting could not be thoroughly explained; strongly suggesting that host genetic factors might also play a significant role in HCV treatment response.Citation1

In 2009–2010, several research groups confirmed the significant association of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at IFNL4 and ITPA genes with PEG-IFN/RBV treatment outcome among HCV-infected patients from around the world.Citation2–Citation7 This breakthrough not only impacted the prognosis and treatment of HCV infection, but also allowed to identify patients with unfavorable alleles, in whom the response to PEG-IFN/RBV treatment would be poor, making them ideal candidates for emerging therapies.

Recently, the development of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) represents an outstanding progress in the field of therapeutic options for HCV chronic infection, which have improved the chance of cure and ameliorated the prognosis of the disease. These new antiviral agents offer a range of advantages compared with their predecessors, have multigenotypic activity, shorter schemes, fewer side effects, and higher cure rates, including for those in advanced stages of infection.Citation8,Citation9 In this current scenario, pharmacogenetics seems to have a reduced usefulness. However, the universal availability of these new treatment regimens – with DAAs alone or in combination with other DAAs or PEG-IFN/RBV – is still not a reality, particularly for HCV patients in the public health system of Latin American countries.Citation10–Citation12

In this review, we summarize the scientific evidences and the potential implications of HCV pharmacogenomics in this rapidly evolving era of anti-HCV drug development.

HCV in Latin America: burden of infection and accessibility to treatment

The burden of HCV infection is expected to increase around the world and Latin America is no exception to this scenario.Citation13

In recent years, different studies have addressed the epidemiology of chronic HCV infection in Latin America.Citation14,Citation15 Nonetheless, there is still a paucity of information in the region, since most of the available data come from spontaneous demand studies in specific groups, which do not faithfully represent the prevalence in the general population.Citation16,Citation17

Despite this limitation, it is estimated an average prevalence rate for HCV of 2.0%±0.25% in the adult population, which represents at least 10 million individuals who are anti-HCV positive in Latin America.Citation14,Citation17,Citation18 On the whole, Latin America has the lowest HCV prevalence compared with others regions around the world. However, these rates vary among countries and even in different areas within the same country.

Most of the HCV-infected individuals in Latin America are in Brazil with more than 2.5 million cases, being among the 10 countries with more cases worldwide.Citation17,Citation19,Citation20 The second largest epidemiologic burden due to HCV is found in Mexico with 1.6 million cases. The third and fourth place is held by Colombia and Argentina with ~690,000 and 342,000 cases, respectively.Citation17,Citation21,Citation22

There is a consensus that most cases occur among people aged 55 years and older.Citation23,Citation24 Likewise, it was estimated that the peak incidence occurred in the mid to late 90s and predicted a slow decline in the prevalence for the next decades as a result of prophylactic measures and the effectiveness of current antiviral agents.Citation17,Citation25 However, due to the fact that 75% of HCV infections evolve into chronicity, the consequences of the natural course of the disease are observed decades after the infection; resulting in future high costs of monitoring, hospitalization, or transplantation for health care systems.Citation17,Citation18,Citation20

As regards HCV genotypes, in Latin America >50% of the cases are caused by genotype 1, followed by 2 or 3 depending on the country.Citation26 This poses a drawback, because the overall cure rate of patients infected with genotype 1 treated with PEG-IFN-α/RBV is low, being ~40%–50%,Citation1 which represents high costs to governments without comparable effectiveness.

In addition, <2% of HCV chronically infected individuals have access to treatment.Citation18,Citation24,Citation25 Particularly, access to standard PEG-IFN/RBV therapy is extremely limited in underserved populations without affiliation to health care systems, which are paradoxically the neediest.

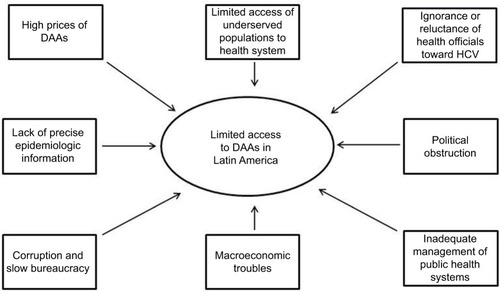

In recent years, several DAAs have been developed. These new antiviral agents represent a great hope for millions of chronically infected individuals because their use may lead to excellent cure rates. Nevertheless, the high cost of these new drugs is one of the major, although not the only, limiting factors for its broad implementation, mainly in low- or lower-middle income countries ().Citation10,Citation11

Figure 1 Limiting factors for the global access to DAAs in Latin America.

In Latin America, the public health care systems often show fragmented schemes mostly concentrated on specific sectors of society. However, in many cases, macroeconomic troubles, political obstruction, and inadequate management led to pay-as-you-go in practice. Although HCV treatment-related costs are mostly responsibility of the public health system, in 50% of cases patients paid treatments from their own pocket, 25% were paid by private insurance, and only 25% treatments were afforded by the public health sector. Moreover, >95% of patients infected with viral hepatitis belong to a low-income population and/or are uninsured, and they cannot afford to pay the current market prices of DAAs ().Citation27

In addition, viral hepatitis is not considered to be a severe health problem by health officials in Latin America, which in turn have manifested ignorance or reluctance toward a state program of detection or treatment of this disease. The lack of precise epidemiologic information about HCV infection is an ongoing difficulty, which translates into the lack of precision of who and how many people are infected and primary risk factors involved.Citation18 Another limiting factor is the corruption and slow bureaucracy to introduce these drugs; even though the pharmaceutical industry has declared a responsibility to create agreements based on the economy of each country for the marketing of the antiviral drugs ().Citation28

At present, the first-wave of NS3/NS4 inhibitors (telaprevir and boceprevir), are the most available DAAs in Latin America.Citation28–Citation30 However, these are no longer used due to their limitations compared with the second-generation inhibitors and those targeted against other HCV genes.Citation31

Therefore, the strategy in the region is to use second-generation DAAs in those countries, where available, and delay patient treatment until arrival in those countries, where they are not.Citation28

In recent years, simeprevir, daclatasvir, and sofosbuvir have been or are being approved and are currently available in Argentina and Brazil.Citation12,Citation28,Citation30 At the moment, the prescription is restricted to older patients with unequivocal signs of liver damage.

In 2014, Gilead announced a voluntary license agreement with several Indian drug manufacturers that allow these companies to produce and sell generic versions of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir. Bolivia is the only country in the region benefited from this measure.

In order to secure some price discounts on these high-cost treatments The Union of South American Nations has proposed the creation of a fund to negotiate centralized purchases of the HCV treatments and began the process of joint purchase of DAAs through the Pan American Health Organization Strategic Fund last year.

HCV pharmacogenomics

In 2009, four independent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) reached the same and definitive conclusion: polymorphisms rs12979860C/T and rs8099917G/T in or near the IL28B gene, also known as IFN lambda 3 (IFN-λ3 or IFNL3) but as the discovery of IFNL4 is now classified as an IFNL4 SNP, significantly affect the spontaneous clearance of acute HCV infection and the response to PEG-IFN/RBV therapy ().Citation2–Citation5 The two GWAS-identified SNPs, rs12979860 and rs8099917 are in low to strong linkage disequilibrium, based on specific populations tested, and both markers were used for predicting response to PEG-IFN and RBV therapy.Citation4,Citation32

Table 1 Genetic factors related to HCV pharmacogenomics

Prokunina-Olsson et al identified a transiently induced region in a new gene member, denoted IFNL4 gene, which shows a dinucleotide variant (rs368234815 or ss469415590 TT/ΔG). This novel interferon is produced only in carriers of ΔG allele carriers and has been related to unsuccessful viral clearance in the presence or absence of treatment ().Citation33 IFNL4 variants rs368234815 and rs12979860 are in high linkage disequilibrium and provide similar predictive information in Asians, and comparable information in Europeans. However, in individuals of African ancestry there is a lower linkage disequilibrium between these markers and rs368234815 is significantly more informative than rs12979860.Citation33–Citation35

Since then, various studies have verified the impact of IFNL4 on HCV infection and treatment outcome across different HCV genotypes,Citation32,Citation36,Citation37 and in individuals coinfected with HIV.Citation38 Although on-treatment predictors are more significantly associated with therapeutic success,Citation39 the viral genotype and the rs368234815 IFNL4 SNP are considered the most powerful pretreatment predictors of response to PEG-IFN/RBV therapy.Citation40

For treatment-naïve patients with genotype 1 infection who are treated with protease inhibitor combinations, IFNL4 genotypes predicts response and also eligible for the shorter durations of therapy.Citation41 Although all IFNL4 genotypes have improved response rates as compared with patients treated with PEG-IFN/RBV only, patients with the favorable IFNL4 genotype still have higher response rates with the protease inhibitor combination in treatment-naïve patients, and these response rates may guide patients and clinicians in their treatment decisions.

Second-wave DAAs, such as sofosbuvir, simeprevir, and daclatasvir, can be administered in combination with PEG-IFN/RBV as triple therapy for patients with HCV genotype 1. In these highly potent regimens, cirrhosis and IFNL4 genotype are still predictors of response.Citation42,Citation43 In contrast, although host genetic factors have a lesser impact on treatment response in IFN- and RBV-free regimens, recent studies have reported that the IFNL4 variants can influence the risk of antiviral resistance.Citation44–Citation46

In addition, recent reports have demonstrated that polymorphisms at other genes could also be related to the risk of PEG-IFN/RBV treatment withdrawal due to drug-related adverse effects.Citation47–Citation49 In this regard, one of the most important treatment-limiting toxicities is RBV-induced hemolytic anemia, which has been linked to two functional polymorphisms in the ITPA gene – a missense variant in exon 2 (rs1127354) and a splice-altering SNP in intron 2 (rs7270101) – and to a nonfunctional one (rs6051702).Citation47,Citation48 These variants induce an inosine triphosphate pyrophosphohydrolase deficiency, a benign red cell enzymopathy associated with a protective effect against RBV-induced hemolytic anemia in HCV-infected patients.Citation47–Citation50

It is important to highlight that ITPA gene polymorphisms are not related to treatment response but to the prediction of RBV-induced hemolytic anemia and thus, the need of dose-reduction or even treatment withdrawal ().Citation49,Citation51

Although new therapies with first-wave protease inhibitors improved SVR, they also increased side effects, such as rash and anemia. Several studies highlighted the ITPA role in predicting anemia in these new regimens.Citation50,Citation52 In the case of second-wave protease (such as simeprevir) and polymerase inhibitors (such as sofosbuvir), effectiveness have been further increased and adverse effects have been considerably reduced. Most of these regimens are RBV-free and they are already approved or undergoing phases II and III studies in different countries.Citation42

Genetic ancestry influences HCV pharmacogenomics in Latin America

Along the end of the Pleistocene (11,700 years ago), a limited number of immigrants arrived to the American continent entering from the eastern edge of Siberia by crossing the Bering Strait. Immigrants explored the territories, some settled, others keep moving south and eastward within the American continent. After a long period of isolation, the continent was explored by Europeans conquerors who – after submitting the aboriginals – started the colonization process. The major transatlantic migratory contribution to Latin America was provided by the Iberians who colonized the major extension of the continent. During the late sixteenth and beginning of the seventeenth century, European colonists introduced West and East Sub-Saharan Africans as working forces. Throughout the Americas, even within the same country, historical differences in pattern of settlement and migration have resulted in a wide range of genetic variation reflecting complex admixed events involving actors of different ancestral background.Citation53

Regarding the maternal lineage, in general, it can be observed a high proportion of Native American maternal ancestry, belonging to haplogroups A–D of the mitochondrial DNA. Certainly, the different proportion found in each country will depend on its own colonization history.Citation54–Citation58

In contrast, the paternal lineage depicts a different scenario. In this case, the European contribution is mainly represented by the R1b haplogroup in the Y-chromosome.Citation55,Citation59 The proportion of the Native American haplogroup Q1a3a, depends on the survival of the Native American males, given their killing carried out by Europeans during the conquest.

Although both male and maternal lineages offer an idea of the different parental populations contributions, autosomal ancestry-informative markers quantify the genetic admixture extent.Citation55 In general, urban towns of Argentina, Mexico, Chile, Colombia, Uruguay, and South of Brazil showed that >55% of the global ancestry belongs to European contribution followed by Native American and <10% of African contribution.Citation55,Citation60,Citation61 Instead, rural Mexico and urban populations in Peru and Bolivia showed the major contribution of Native American ancestry in part due to the high population density of aboriginal in the region at the moment of the conquest.Citation60–Citation63

Latin America experienced one of the largest admixture processes in a reduced span of time of just 20 generations. These circumstances have important implications for the expected relative proportion of ancestral genetic makeup with potential effects on disease susceptibilities, ability to metabolize therapeutic compounds demonstrating the need to genetic ancestry determination in future genetic association studies.

Several epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that the allele frequencies of IFNL4 and ITPA predictive SNPs exhibit variations among worldwide populations with different ancestry background.Citation32,Citation64 However, these data obtained from well-defined ethnic groups cannot be extrapolated to genetically admixed and multiethnic populations, such as those in Latin America.Citation65

Several research groups have confirmed the significant association of IFNL4 and ITPA SNPs with PEG-IFN/RBV treatment outcome among HCV-infected Latin American patients.Citation66–Citation72 Meanwhile, in the general population of the region, these predictive polymorphisms exhibit extremely variable frequencies.Citation73,Citation74 Nevertheless, in order to avoid drawing false conclusions, it is important to highlight that the high heterogeneity of Latin American populations was not taken into consideration by these groups and, therefore, the analysis of genetic ancestry was not carried out in these studies.Citation65

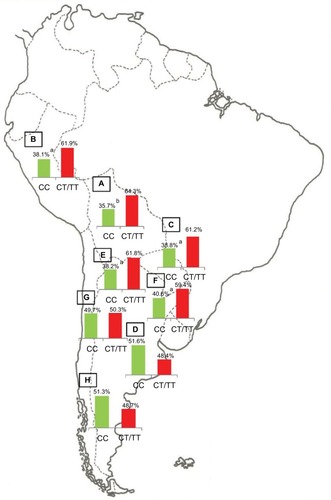

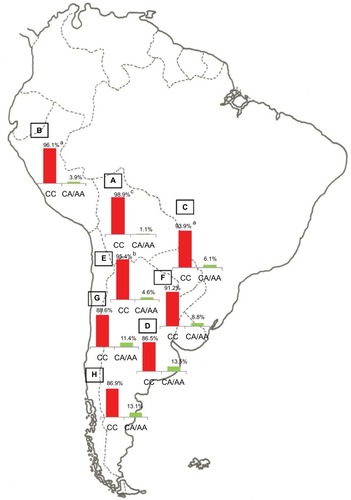

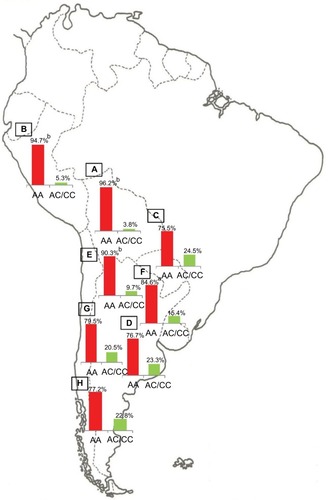

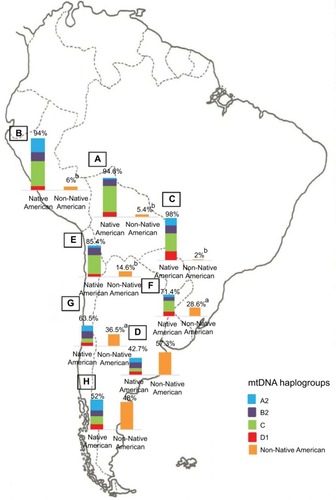

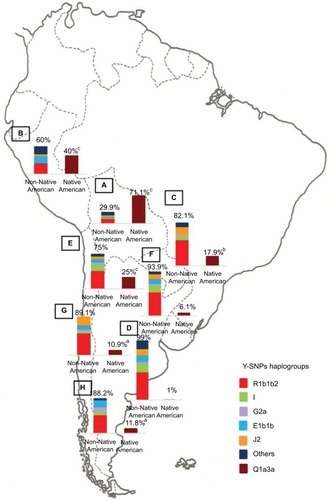

The population diversity in Latin American, with trihybrid ancestral roots and five centuries of admixture, cannot be detected by color/race self-identification and should be described by molecular approaches. In this regard, recent studies have concluded that the distribution of these SNPs is closely related to the genetic ancestry in Latin America.Citation35,Citation75–Citation78 A study carried out among 2150 non-HCV-infected individuals from Argentina, Peru, Bolivia, and Paraguay, showed that the frequency of IFNL4 and ITPA SNPs exhibits a specific geographical pattern of distribution, even within the same country (–), and is closely related to the maternal and paternal ancestry of the population ( and ). In fact, the prevalence of favorable genotypes is significantly higher in populations with European ethnicity, intermediate in admixed individuals, and the lowest in populations with Native American ancestry background.Citation75,Citation76 These findings were confirmed in western Mexico, where the TT/GG/ΔG risk haplotype in the IFNL4 gene predominates in Native Americans when compared with the “Mestizos” (admixed) group.Citation35 With respect to the association of these SNPs with HCV clearance in the presence or absence of PEG-IFN/RBV treatment, the protective alleles were more frequently observed among admixed Mexicans with spontaneous clearance of HCV infection.Citation35 Moreover, studies carried out among HCV chronic patients from Brazil revealed that IFNL4 polymorphisms predict therapy response in patients with admixed ancestry.Citation77,Citation78 Interestingly, this association is influenced by ancestry; being the African genetic contribution higher among the nonresponder patients with the rs12979860 TT genotype, whereas the Native American and European genetic ancestry prevail in the SVR group.Citation77

Figure 2 IFNL4 SNP rs12979860.

Abbreviation: SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Figure 3 ITPA SNP rs1127354.

Abbreviations: ITPA, inosine triphosphatase; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Figure 4 ITPA SNP rs7270101.

Abbreviations: ITPA, inosine triphosphatase; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Figure 5 Maternal ancestry.

Abbreviation: mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA.

Figure 6 Paternal ancestry.

Abbreviation: Y-SNPs, Y-chromosome single-nucleotide polymorphisms.

Implications in the era of DAAs

Several studies carried out in different geographical scenarios have shown that DAAs implementation is cost-effectiveness per person treated, but pent-up demand for treatment will create challenges for financing.Citation10,Citation79,Citation80 Cost-effectiveness studies have not been conducted in Latin America and, therefore, the implication that these new therapies might have in health-related economics is unpredictable and its relevance in HCV control will probably remain negligible as long as access to the therapy cannot be expanded.Citation81

In this region, the high rate of infections with HCV genotype 1 and the high frequency in Native American populations of the TT genotype of IFNL4 SNP rs12979860 – markers associated with poor response to PEG-IFN/RBV therapy in both casesCitation35,Citation75–Citation78 – support the hypothesis that the implementation of IFN-free regimen should be beneficial in terms of cost–benefit. However, before or until global availability to DAAs is achieved, the identification of host predictive markers of antiviral therapy outcome could still be useful, as it will help prioritize DAA access.

Furthermore, it is important to highlight that IFNL4 not only plays an important role on establishing the likelihood of treatment response with PEG-IFN/RBV and to triple (single DAA plus PEG-IFN/RBV) and quadruple (two DAAs plus PEG-IFN/RBV) regimens,Citation41,Citation42 but also exert, an effect on the early viral kinetics in HCV chronic patients receiving the emerging IFN and RBV-free schemes.Citation82,Citation83 In addition, recent studies have reported that the presence of resistance variants, number, and diversity of NS5A quasispecies is strongly associated with favorable IFNL4 genotypes, probably as a consequence of the fact that patients with the beneficial genotypes induce a more efficient antiviral response that results either in viral clearance or selection for viral adaptations. This regulating influence of host genetic factors on the nature of the viral quasispecies could be of clinical interest for consideration of IFN-free treatment options for patients with known IFNL4 status.Citation44–Citation46

In Latin America, pharmacogenomics could still provide an instrument to optimize HCV management, taking into account ethnic differences and explaining the variability in treatment response. As a consequence, HCV pharmacogenetics will still represent an ongoing challenge for Latin American clinicians and hepatologists in the treatment decision making.

Conclusion

In the last 5 years, resonant advances related to infection by hepatitis C have been obtained, making conceivable that HCV chronic infection will soon become an easier-to-treat disease.

Nowadays, HCV treatment varies throughout the world because some regions have access to the new DAAs, whereas other areas have access only to PEG-IFN/RBV. Although the high prevalence of HCV genotype 1 in Latin America and unfavorable predictive SNPs among Native Americans highlight the need to implement new treatment regimens in these populations, the universal accessibility to DAAs is still not a reality in the region. Therefore, the PEG-IFN/RBV treatment will still be the only therapy available until the costs of the new drugs have decreased and their access to HCV patients has globalized.

In this review, the report of several studies concerning pharmacogenetic factors related to HCV treatment in Latin America might help to adjust the regional treatment policies for HCV infection based on greater certainty in studies with populations with such genetic characteristics. They also confirm that, in this vast territory, there are populations with different genotypic characteristics that might, depending on the situation, require different approaches to treatment and research.

In this perspective, the assessment of host genetic markers in all HCV patients to predict response and evaluate the risk–benefit of available therapies might be useful to improve strategies and fight the infection and could be a cost-effective means of risk stratification in the developing countries. In this regard, several scientific societies and studies have declared that, until global access to DAAs is guaranteed, treatment-naïve patients exhibiting favorable clinical, genetic, and virologic profiles could still benefit with the PEG-IFN/RBV regimen; thus restricting the use of newer and expensive treatment schemes for “difficult to treat” patients.Citation22,Citation29,Citation41,Citation70,Citation84–Citation87

In future decades, it is expected that, particularly in the developing countries, the burden of HCV disease increases due to the absence of an effective vaccine, the insufficient amount of public awareness, and preventive measures.Citation13,Citation14,Citation17 Therefore, regardless of the great therapeutic advances, improvements in HCV surveillance, epidemiologic mapping, testing, prevention, and therapy are urgently needed. The challenge now is to overcome barriers to HCV testing and improve access to antiviral treatment in the low- and middle-income countries. Guarantee access to medicines is a joint responsibility of governments, multilateral agencies, and nongovernmental organizations. But also, pharmaceutical companies should be a part of the solution. Eventually, the global HCV control will be achieved with the joint efforts of governments, researchers, and public health workers.

Acknowledgments

This review was partly supported by grants from “Research Council of the Italian Hospital of Buenos Aires”, “Instituto Universitario del Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires”, and PICT 2014-1675.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ConteducaVSansonnoDRussiSPavoneFDammaccoFTherapy of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the era of direct-acting and host-targeting antiviral agentsJ Infect201468112024012819

- SuppiahVMoldovanMAhlenstielGInterleukin 28B is associated with response to Hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapyNat Genet20094111100110419749758

- TanakaYNishidaNSugiyamaMGenome-wide association of Interleukin 28B with response to interferon alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis CNat Genet200941101105110919749757

- GeDFellayJThompsonAJGenetic variation in interleukin 28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearanceNature2009461726239940119684573

- RauchAKutalikZDescombesPGenetic variation in interleukin 28B is associated with chronic hepatitis C and treatment failure: genome-wide association studyGastroenterology201013841338134520060832

- FellayJThompsonAJGeDITPA gene variants protect against anemia in patients treated for chronic hepatitis CNature2010464728740540820173735

- SakamotoNTanakaYNakagawaMITPA gene variant protects against anemia induced by pegylated interferon-α and ribavirin therapy for Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis CHepatol Res201040111063107120977565

- BarrittAS4thFriedMWMaximizing opportunities and avoiding mistakes in triple therapy for hepatitis C virusGastroenterology201214261314132322537438

- SadlerMDLeeSSRevolution in hepatitis C antiviral therapyBr Med Bull20151131314425680808

- ReinDBWittenbornJSSmithBDLiffmannDKWardJWThe cost-effectiveness, health benefits, and financial costs of new antiviral treatments for hepatitis C virusClin Infect Dis201561215716825778747

- Silva-VidalKVMéndez-SánchezNThe good, the bad and the ugly of the new treatments for hepatitis C virusAnn Hepatol201413557457525152995

- OlmedoDBCaderSAPortoLCIFN-λ gene polymorphisms as predictive factors in chronic hepatitis C treatment-naive patients without access to protease inhibitorsJ Med Virol201587101702171525970604

- CookeGSLemoineMThurszMViral hepatitis and the Global Burden of Disease: a need to regroupJ Viral Hepat201320960060123910643

- SzaboSMBibbyMYuanYThe epidemiologic burden of hepatitis C virus infection in Latin AmericaAnn Hepatol201211562363522947522

- Alvarado-MoraMVPinhoJREpidemiological update of hepatitis B, C and delta in Latin AmericaAntivir Ther2013183 Pt B42943323792375

- FlichmanDMBlejerJLLivellaraBIPrevalence and trends of markers of hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and human Immunodefi-ciency virus in Argentine blood donorsBMC Infect Dis20141421824755089

- KershenobichDRazaviHASánchez-AvilaJFTrends and projections of hepatitis C virus epidemiology in Latin AmericaLiver Int201131Suppl 21829

- PanduroARomanSNeed of righteous attitudes towards eradication of hepatitis C virus infection in Latin AmericaWorld J Gastroenterol201622225137514227298556

- PereiraLMMartelliCMMoreiraRCPrevalence and risk factors of Hepatitis C virus infection in Brazil, 2005 through 2009: a cross-sectional studyBMC Infect Dis2013136023374914

- FerreiraPRBrandão-MelloCEEstesCDisease burden of chronic hepatitis C in BrazilBraz J Infect Dis201519436336826051505

- RidruejoEBessoneFDaruichJRHepatitis C virus infection in Argentina: burden of chronic diseaseWorld J Hepatol201681564965827239258

- Lozano-SepulvedaSBryan-MarrugoOMerino-MascorroJRivas-EstillaAMApproachability to the new anti-HCV direct acting antiviral agents in the Latin American contextFuture Virol20161113946

- BruggmannPBergTØvrehusALHistorical epidemiology of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in selected countriesJ Viral Hepat201421Suppl 153324713004

- RazaviHWakedISarrazinCThe present and future disease burden of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection with today’s treatment paradigmJ Viral Hepat201421Suppl 1345924713005

- HatzakisAChulanovVGadanoACThe present and future disease burden of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections with today’s treatment paradigm – volume 2J Viral Hepat201522Suppl 1264525560840

- MessinaJPHumphreysIFlaxmanAGlobal distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypesHepatology2015611778725069599

- SutharABHarriesADA public health approach to hepatitis C control in low- and middle-income countriesPLoS Med2015123e100179525757228

- Méndez-SánchezNParanáRCheinquerHLatin American Association for the Study of the Liver recommendations on treatment of hepatitis CAnn Hepatol201413Suppl 2s4s66

- Sánchez-ÁvilaJFDehesa-ViolanteMMéndez-SánchezNMexican consensus on the diagnosis and management of hepatitis C infectionAnn Hepatol201514Suppl 154825983318

- BoteroRCTagleMNew therapies for hepatitis C: Latin American perspectivesClin Liv Dis201551810

- AASLD/IDSA HCV Guidance PanelHepatitis C guidance: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with hepatitis C virusHepatology201562393295426111063

- ThomasDLThioCLMartinMPGenetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virusNature2009461726579880119759533

- Prokunina-OlssonLMuchmoreBTangWA variant upstream of IFNL3 (IL28B) creating a new interferon gene IFNL4 is associated with impaired clearance of hepatitis C virusNat Genet201345216417123291588

- AkaPVKuniholmMHPfeifferRMAssociation of the IFNL4-ΔG allele with impaired spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virusJ Infect Dis2014209335035423956438

- Gonzalez-AldacoKRebello PinhoJRRomanSAssociation with spontaneous hepatitis C viral clearance and genetic differentiation of IL28B/IFNL4 haplotypes in populations from MexicoPLoS One2016111e014625826741362

- MangiaAThompsonAJSantoroRAn IL28B polymorphism determines treatment response of hepatitis C virus genotype 2 or 3 patients who do not achieve a rapid virologic responseGastroenterology2010139382182720621700

- SarrazinCSusserSDoehringAImportance of IL28B gene polymorphisms in hepatitis C virus genotype 2 and 3 infected patientsJ Hepatol201154341542121112657

- RallonNINaggieSBenitoJMAssociation of a single nucleotide polymorphism near the interleukin-28B gene with response to hepatitis C therapy in HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patientsAIDS2010248F23F2920389235

- MangiaAThompsonAJSantoroRLimited use of interleukin 28B in the setting of response-guided treatment with detailed on-treatment virological monitoringHepatology201154377278021626525

- LiYYangLShaKLiuTZhangLCorrelation of interferon-lambda 4 ss469415590 with the hepatitis C virus treatment response and its comparison with interleukin 28b polymorphisms in predicting a sustained virological response: a meta-analysisInt J Infect Dis201653525827810523

- MuirAJGongLJohnsonSGClinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC)Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines for IFNL3 (IL28B) genotype and PEG interferon-α-based regimensClin Pharmacol Ther201495214114624096968

- SerfatyLHow to optimize current therapy in hepatitis C virus genotype 1 patients. Predictors of response to interferon-based therapy with second wave direct acting antiviralsLiver Int201535Suppl 1182025529083

- MeissnerEGBonDProkunina-OlssonLIFNL4-ΔG genotype is associated with slower viral clearance in hepatitis C, genotype-1 patients treated with sofosbuvir and ribavirinJ Infect Dis2014209111700170424367041

- AkamatsuSHayesCNOchiHAssociation between variants in the interferon lambda 4 locus and substitutions in the hepatitis C virus non-structural protein 5AJ Hepatol201563355456325849245

- ItakuraJKurosakiMTakadaHNaturally occurring, resistance-associated hepatitis C virus NS5A variants are linked to interleukin-28B genotype and are sensitive to interferon-based therapyHepatol Res20154510E115E12125564756

- PeifferKHSommerLSusserSInterferon lambda 4 genotypes and resistance-associated variants in patients infected with hepatitis C virus genotypes 1 and 3Hepatology2016631637326406534

- StättermayerAFScherzerTBeinhardtSRutterKHoferHFerenciPReview article: genetic factors that modify the outcome of viral hepatitisAliment Pharmacol Ther201439101059107024654629

- TanakaYKurosakiMNishidaNGenome-wide association study identified ITPA/DDRGK1 variants reflecting thrombocytopenia in pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis CHum Mol Genet201120173507351621659334

- ThompsonAFellayJPatelKVariants in the ITPA gene protect against ribavirin-induced hemolytic anemia and decrease the need for ribavirin dose reductionGastroenterology201013941181118920547162

- D’AvolioACusatoJDe NicolòAAllegraSDi PerriGPharmacogenetics of ribavirin-induced anemia in HCV patientsPharmacogenomics201617892594127248282

- KurosakiMTanakaYNishidaNModel incorporating the ITPA genotype identifies patients at high risk of anemia and treatment failure with pegylated-interferon plus ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis CJ Med Virol201385344945823297176

- AkamatsuSHayesCNTsugeMRibavirin dose reduction during telaprevir/ribavirin/peg-interferon therapy overcomes the effect of the ITPA gene polymorphismJ Viral Hepat201522216617424930407

- ReichDPattersonNCampbellDReconstructing native American population historyNature2012488741137037422801491

- FridmanCGonzalezRSPereiraACCardenaMMHaplotype diversity in mitochondrial DNA hypervariable region in a population of southeastern BrazilInt J Legal Med2014128458959324846100

- CorachDLaoOBobilloMCInferring continental ancestry of argentineans from autosomal, Y-chromosomal and mitochondrial DNAAnn Hum Genet2010741657620059473

- de Saint PierreMBraviCMMottiJAn alternative model for the early peopling of southern South America revealed by analyses of three mitochondrial DNA haplogroupsPLoS One201279e4348622970129

- HeinzTCárdenasJMÁlvarez-IglesiasVThe genomic legacy of the transatlantic slave trade in the yungas valley of BoliviaPLoS One2015108e013412926263179

- SandovalJRLacerdaDRAcostaOThe genetic history of peruvian quechua-lamistas and chankas: uniparental DNA patterns among autochthonous Amazonian and Andean PopulationsAnn Hum Genet20168028810126879156

- CárdenasJMHeinzTPardo-SecoJThe multiethnic ancestry of Bolivians as revealed by the analysis of Y-chromosome markersForensic Sci Int Genet20151421021825450796

- González-SobrinoBZPintado-CortinaAPSebastián-MedinaLGenetic diversity and differentiation in Urban and Indigenous populations of Mexico: patterns of mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome lineagesBiodemography Soc Biol2016621537227050033

- HomburgerJRMoreno-EstradaAGignouxCRGenomic insights into the ancestry and demographic history of South AmericaPLoS Genet20151112e100560226636962

- HeinzTAlvarez-IglesiasVPardo-SecoJAncestry analysis reveals a predominant Native American component with moderate European admixture in BoliviansForensic Sci Int Genet20137553754223948324

- VulloCGomesVRomaniniCAssociation between Y haplogroups and autosomal AIMs reveals intra-population substructure in Bolivian populationsInt J Legal Med2015129467368024878616

- AltshulerDMGibbsRAPeltonenLInternational HapMap 3 ConsortiumIntegrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populationsNature20104677311525820811451

- Suarez-KurtzGPharmacogenetics in the brazilian populationFront Pharmacol2010111821833165

- DelvauxNCostaVDCostaMMInosine triphosphatase allele frequency and association with ribavirin-induced anaemia in Brazilian patients receiving antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis CMem Inst Oswaldo Cruz2015110563664326154744

- RidruejoESolanoAMarcianoSGenetic variation in interleukin-28B predicts SVR in hepatitis C genotype 1 Argentine patients treated with PEG IFN and ribavirinAnn Hepatol201110445245721911885

- VenegasMVillanuevaRAGonzalezKBrahmJIL28B polymorphisms associated with therapy response in Chilean chronic hepatitis C patientsWorld J Gastroenterol201117313636363921987611

- FerreiraPRSantosCCortesRAssociation between IL28B gene polymorphisms and sustained virological response in patients coinfected with HCV and HIV in BrazilJ Antimicrob Chemother201267250951022146876

- Martinez-GomezLEChavez-TapiaNCBurguete-GarciaAIIL28B polymorphisms predict the response to chronic hepatitis C virus infection treatment in a Mexican populationAnn Hepatol201211687688123109451

- AlvesCFGrottCSLungeVRInterferon lambda 4 (IFNL4) gene polymorphism is associated with spontaneous clearance of HCV in HIV-1 positive patientsGenet Mol Biol201639337437927560987

- Sixtos-AlonsoMSAvalos-MartinezRSandoval-SalasRA genetic variant in the interleukin 28B gene as a major predictor for sustained virologic response in chronic hepatitis C virus infectionArch Med Res201546644845326189761

- GalvanCAElbarchaOCFernandezEJBeltramoDMSoriaNWDistribution of polymorphisms in cytochrome P450 2B6, histocompatibility complex P5, chemokine coreceptor 5, and interleukin 28B genes in inhabitants from the central area of ArgentinaGenet Test Mol Biomarkers201216213013321854194

- SozaALopez-LastraMIL28B Polymorphisms among Latin American HCV patientsCurr Hepatitis Rep2013124276279

- TrinksJHulaniukMLCaputoMDistribution of genetic polymorphisms associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) antiviral response in a multiethnic and admixed populationPharmacogenomics J201414654955424841973

- TrinksJHulaniukMLCaputoMDistribución de polimorfismos de nucleótido simple (SNPs) predictores de la respuesta al tratamiento antiviral en la infección crónica por el virus de la hepatitis C (HCV) en las distintas regiones geográficas de Argentina [Distribution of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) predictive of antiviral treatment response in hepatitis C virus (HCV) chronic infection in different geographic regions in Argentina]Medicina (B Aires)201474Suppl 3S117S118 Spanish

- CavalcanteLNAbe-SandesKAngeloALIL28B polymorphisms are markers of therapy response and are influenced by genetic ancestry in chronic hepatitis C patients from an admixed populationLiver Int201232347648622098416

- de Seixas Santos NastriACde Mello MaltaFDinizMAAssociation of IFNL3 and IFNL4 polymorphisms with hepatitis C virus infection in a population from southeastern BrazilArch Virol201616161477148426973228

- ChidiAPRogalSBryceCLCost-effectiveness of new antiviral regimens for treatment-naïve U.S. veterans with hepatitis CHepatology201663242843626524695

- NajafzadehMAnderssonKShrankWHCost-effectiveness of novel regimens for the treatment of hepatitis C virusAnn Intern Med2015162640751925775313

- EdwardsDJCoppensDGPrasadTLRookLAIyerJKAccess to hepatitis C medicinesBull World Health Organ2015931179980526549908

- ChuTWKulkarniRGaneEJEffect of IL28B genotype on early viral kinetics during interferon-free treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis CGastroenterology2012142479079522248659

- MontoARyanJIs IL28B genotype associated with more than one aspect of viral clearance?Hepatology20125662414241623212777

- European Association for the Study of the LiverEASL Practice Guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infectionJ Hepatol201460239242024331294

- Italian Association for the Study of the Liver (AISF)Triple therapy with first-generation protease inhibitors for patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C: recommendations of the Italian association for the study of the liver (AISF)Dig Liver Dis2014461182424119482

- PearlmanBLEhlebenCHepatitis C genotype 1 virus with low viral load and rapid virologic response to peginterferon/ribavirin obviates a protease inhibitorHepatology2014591717723873583

- AndriulliANardiADi MarcoVAn a priori prediction model of response to peginterferon plus ribavirin dual therapy in naïve patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis CDig Liver Dis201446981882524953209