Abstract

Purpose:

To examine the relation between variant alleles in 3 CYP450 genes (CYP2D6, CYP2C9 and CYP2C19), interacting drugs and akathisia in subjects referred to a forensic psychiatry practice in Sydney, Australia.

Patients and methods:

This paper concerns 10/129 subjects who had been referred to the first author’s practice for expert opinion or treatment. More than 120 subjects were diagnosed with akathisia/serotonin toxicity after taking psychiatric medication that had been prescribed for psychosocial distress. They were tested for variant alleles in CYP450 genes, which play a major role in Phase I metabolism of all antidepressant and many other medications. Eight had committed homicide and many more became extremely violent while on antidepressants. Ten representative case histories involving serious violence are presented in detail.

Results:

Variant CYP450 allele frequencies were higher in akathisia subjects compared with random primary care patients tested at the same facility. Ten subjects described in detail had variant alleles for one or more of their tested CYP450 genes. All but two were also on interacting drugs, herbals or illicit substances, impairing metabolism further. All those described were able to stop taking antidepressants and return to their previously normal personalities.

Conclusion:

The personal, medical, and legal problems arising from overuse of antidepressant medications and resulting toxicity raise the question: how can such toxicity events be understood and prevented? The authors suggest that the key lies in understanding the interplay between the subject’s CYP450 genotype, substrate drugs and doses, co-prescribed inhibitors and inducers and the age of the subject. The results presented here concerning a sample of persons given antidepressants for psychosocial distress demonstrate the extent to which the psychopharmacology industry has expanded its influence beyond its ability to cure. The roles of both regulatory agencies and drug safety “pharmacovigilantes” in ensuring quality and transparency of industry information is highlighted.

Introduction

Many, if not most, medicines used to alter brain chemistry interact with the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) system of enzymes, as substrates, inducers or inhibitors. The activity of this enzyme system is genetically determined and is also affected by other intrinsic factors such as age, gender, and comorbidity as well as extrinsic factors such as nutrition and drug–drug interactions. The CYP450 superfamily of genes is the major pathway of the Phase I oxidative metabolism of many drugs currently marketed. All antidepressants are metabolized by the enzymes CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP3A4, and CYP1A2 to varying degrees, with the first three contributing most to metabolism.Citation1–Citation3 Variability in metabolism and treatment response to antidepressants can be affected by genetic polymorphisms. The general population can be broadly divided by CYP450 genetic testing into poor, intermediate, or extensive (normal or “wild-type”) metabolizers for CYPs 2C9, 2C19 and 2D6, with an additional category of ultrarapid metabolizers for CYP2C19 (due to *17 allele) and CYP2D6 due to duplications of extensive metabolizer alleles.Citation1–Citation3 The Karolinska group, led by Ingelman-Sundberg, maintains a website summarizing the relevant literature on the metabolizing functions of different alleles.Citation4 shows the nomenclature conventions for naming the non-variant and variant alleles, with examples of some of the clinical consequences that may result from having one or more variant alleles for a given CYP450 gene.Citation5

Table 1 Drug metabolizing CYP450 phenotypes and polymorphic CYP450 alleles of importance for drug response

Drug metabolism phenotype can be affected by the medications taken. For example, genetically extensive metabolizers will metabolize drugs like poor metabolizers after taking CYP inhibitors (notably fluoxetine and paroxetine) that reduce or eliminate enzyme activity.Citation6,Citation7 With some drugs and prodrugs such as codeine, ultrarapid metabolism producing an active metabolite was found to be problematic.Citation8 Ultrarapid metabolism at CYP2D6 (due to allele duplications), seems to be strongly associated with a large number of deaths from intoxication and suicide.Citation9–Citation11 The ultrarapid metabolizer allele CYP2C19*17 is likely to cause therapeutic failures in drug treatment with antidepressants, but no reports of serious adversity associated with it have been published to date.Citation12 High or fast-changing levels of psychotropic substances can cause unpredictable toxicity leading to violent behavioral effects, including akathisia.Citation13,Citation14 These effects are listed in product information (PI) or “label”; product information for drugs used in the USA can be found on the website of the US Food and Drug Administration.Citation15 Extrapyramidal side effects (EPSEs), including akathisia, may develop very fast in persons with slower CYP450 metabolism.Citation16 These effects were first identified in children whose cytochrome systems and other metabolic pathways were not yet fully developed or may have not yet been induced.

Further information on CYP450 attribution for the drugs and substances described in this paper is presented in , adapted from Wynn et al, whose Clinical Manual of Drug Interaction Principles for Medical Practice has been the authors’ invaluable tool for understanding drug–gene and drug–drug interpretations.Citation1 It accords with Flockhart’s Cytochrome P450 Drug Interaction Table.Citation17 Information about the therapeutic window comes for Baumann et al.Citation18

Table 2 Drugs involved in these cases, with therapeutic windows and CYP450 attribution as metabolic substrates, inhibitors, and inducers

We present here a summary of findings from a group of subjects who were referred to the forensic psychiatry practice of Yolande Lucire for psychiatric assessment. They were found to be experiencing adverse drug reactions, manifestations of neurotoxicity/akathisia, and were tested for variant alleles in CYP450 genes. We present some essential features, including genotype, drug regime, and outcomes, along with rationales based on the research literature in CYP450 drug metabolism, for a selected group of subjects who represent the extreme violent end of the spectrum for akathisic subjects.

Patients and methods

Study setting and population description

In an ongoing, naturalistic study, 129 people were referred or self-referred to Yolande Lucire’s forensic psychiatry practice for expert opinion and were diagnosed as having medication-induced disorders, serious adverse drug reactions to drugs metabolized by CYP450 enzymes. They were tested for variant alleles for three CYP450 genes (2D6, 2C9, 2C19); nine more were tested because they were first-degree relatives. The total number of persons tested was 138. Four swabs produced incomplete results.

Sources of referral

Of the 129, 92 were referred by lawyers for various issues; 29/92 were being treated for compensable work stress; 9/92 for compensable physical injuries; and a further 30/92 faced criminal charges because they had committed a variety of offences, ranging from trespass, running amok, and malicious damage to violence resulting in homicide; 6/92 had been brought before professional tribunals for behavioral changes; 7/92 had issues with child custody; and the remainder had a variety of problems.

Following akathisic, suicidal, self-mutilating, and/or homicidal behavior on psychiatric drugs, 29/129 persons had self-referred, requesting to be research subjects and they conformed to the study’s criteria for testing. Another 11/129 were friends and neighbors who requested testing, asking if CYP450 genotyping could shed light on their adverse drug reactions.

Reasons for testing

Five of the 129 had experienced lack of response or adversity with nonpsychiatric drugs: metoclopramide (an akathisia inducer) (1), clopidogrel (1), opioids (3). The other 124 were found to be experiencing adverse drug reactions for drugs used in psychiatry and/or zolpidem. They had reported symptoms or shown signs of akathisia-related suicidal and/or homicidal impulses, dysphoria, which overlapped with manic shift with behavioral disturbance and symptoms of serotonin toxicity, in the range described by Breggin.Citation19 Three were investigated after bizarre sleep activities while on zolpidem.

Clinical characteristics of the tested population

Of the tested population, 86 seemed to have been fully functioning workers or students experiencing various degrees of psychosocial stress, who were being treated for compensable injuries and/or stressors. Four had been diagnosed with mental illness before they used substances, medicinal or other: two with schizophrenia and two with bipolar disorder. At least 26 were given psychiatric medications following or during the use of illicit substances such as cannabis, amphetamines, and ecstasy (MDMA), three had taken hypericum before taking antidepressants and had developed similar adversity on that. Three had received attention for anorexia nervosa, three for the effects of sexual abuse, two for brain injuries, one for organophosphate poisoning, and one for epilepsy. The expected array of human problems was disclosed, with overlapping alcohol overuse (2), personality disorders (6), and bereavements (4). The premedication conditions of six could not be reliably assessed.

Outcomes of psychiatric medications in this population

Out of the 129, eight had committed homicide, three had committed suicide and one had sleepwalked to her death. The first author restored 16 to their previously normal personalities by supervising a very slow and safe withdrawal of medications in the correct order. Fifty-six others had stopped taking the drugs, with or without medical support, after intervals varying from one day to several years. Some had stopped taking the drugs after consulting pharmacists or protocols available on the Internet. These reported recovery. Thirty reported back that their treating doctors were unresponsive to genetic information. Some were forced by court orders at the instigation of the prescribing physician to continue taking the same drugs by injection. Those who were not allowed to stop medications included 4 of the 16 who had been imprisoned, while 12 of those who had been imprisoned for akathisia-related events reported recovery. Twelve had manifested neuroleptic-induced deficits, in one case demonstrable on magnetic resonance imaging, and, in two, deterioration involving loss of cognitive function was confirmed by intelligence tests. Two suffered strokes and five had become diabetic when olanzapine was added (without success) in an attempt to quell antidepressant-induced hallucinosis. Those taking zolpidem experienced various unmotivated sleep activities, including a death that occurred while sleepwalking and a homicide.

Twenty-six were known to be taking illicit or herbal psychoactive substances metabolized by CYP450 and had been treated with antidepressants, antipsychotics, atypicals, and enforced zuclopenthixol depot injections (all also metabolized by CYP450) and remained under psychiatric care until they stopped medication or committed suicide. Their treating doctors are among the 30 unresponsive to genetic information. This attitude may be related to a popular but contested belief that cannabis accelerates the onset of mental illness.Citation20 It has not been possible to follow up the fates of 26 of them.

Genetic testing

The CYP450 genetic testing for all but one of the described subjects was carried out at Healthscope Molecular in Melbourne, Australia. Healthscope Molecular tested for CYP2D6: *2 (functional allele), *9, *10, *17, *41 (partial function alleles) and *3, *4, *5, *6, *7, and *8 (non-functional alleles) as well as multiple copies (potential ultrarapid metabolizers); CYP2C9: *2 and *3 (non-functional alleles); CYP2C19: *2 and *3 (partial function alleles) and after 2007, 2C19*17 (ultrarapid metabolizer allele), using the Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA) ABI3130. In the other case (Subject 5 in ), gene testing was carried out by Genelex (Seattle, WA).

Table 3 Information on subjects’ drug regimes, CYP450 genotypes, criminal acts, and outcomes for ten of those suffering violent akathisia

Results

The association among variant alleles, drug metabolism, and severe akathisia

Of 138 persons tested for CYP450 genes, 129 had experienced adversity, mainly akathisia, due to psychiatric drugs, and nine were first-degree relatives of those treated, who also had a history of adversity on other drugs. Forty-nine akathisia subjects were tested for six alleles in three CYP450 genes at Diversity Health Institute of Westmead Hospital, Westmead, New South Wales, Australia. The significantly increased frequency of multiples of diminished activity alleles in akathisia subjects compared with a sample of Western Sydney clinical patients has been previously reported.Citation21

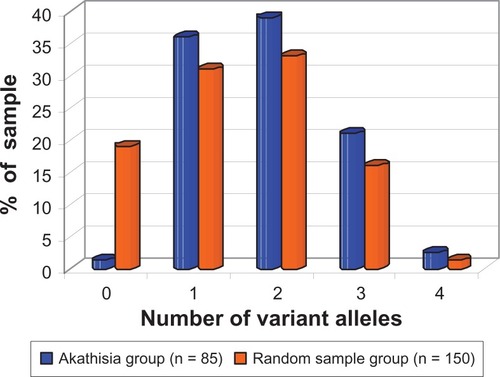

Eighty-five akathisia subjects fully tested (or retested) at Healthscope Molecular (see Patients and methods for allele coverage) were compared with a sample of 150 randomly selected primary care patients referred for other tests and tested for CYP450 genes at the same laboratory in 2007.Citation22 This comparison revealed significantly higher frequencies of variant alleles in akathisia subjects in comparison with the primary care sample, and significantly lower frequencies of subjects with extensive metabolizer alleles (). All but 1/85 (98.8%) of akathisia subjects possessed at least one variant allele for the three CYP450 genes tested (CYPs 2C9, 2C19, and 2D6), while 81% of the randomly selected primary care patients possessed at least one variant allele; 19% of the randomly selected primary care patients had no variant alleles compared with 1.2% of akathisia patients (). The odds ratio for this comparison was 19.3 (95% CI: 2.57–144.5; P = 0.00014; Fisher two-tailed exact probability test), therefore, the null hypothesis that this difference in variant allele frequency between the two samples occurred by chance alone can be safely dismissed. The 2007 randomly selected primary care patient data from Healthscope Molecular identified 2D6*2 as a “variant.” 2C19*17, since it was not tested for at that time, was subsumed into the nonvariant 2C19*1 category; the comparison in was made on this basis. An analysis of CYP450 alleles after 2007 (the case for all akathisia subjects tested at Healthscope and which included 2C19*17) that considered their functionality, as recognised presently, revealed the following: 10/85 had no diminishing (as opposed to variant) mutations, 37/85 had one, 29/85 had two, 8/85 had three, and 1/85 had four diminishing mutations. Among the 10/85 with no diminishing mutations, 2D6*2, which is nominally but not invariably extensive,Citation23 appeared in 4/10 and was the sole variant allele. Four out of ten carried the ultrarapid 2C19*17 in conjunction with 2D6*2. Of the 85, 28 showed 2C19*17; two of these were homozygous (*17/*17) and *17 was combined with diminishing mutations in 21/28. The possible significance of the *17 allele is elaborated further in the Discussion. One subject carried the gene multiplication 2D6*1XN (ultrarapid) as a sole mutation and another carried 2D6*2XN, but not on its own. Only one akathisia subject carried the *1 allele exclusively (homozygous) across all three genes.

Figure 1 Prevalence of individuals with different numbers of variant CYP450 alleles in two groups: akathisia subjects and randomly selected primary care patients.

The 10 subjects described in detail in suffered from severe akathisia, induced by antidepressants prescribed for various forms of psychosocial distress. In 9/10 cases shown in , the individual was on drugs for which genotyping would predict impaired metabolism, as they were intermediate or poor metabolizers for those drugs. Eight of the ten were taking other interacting drugs, substances, or herbal preparations.

The subjects

None of the ten subjects described had any history of mental illness; none had been violent before. All recovered from akathisia after stopping the medication without assistance or supervision and, frequently, against medical advice.

Subject 1 (35-year-old female; genotypes: CYP2D6 *4/*41, CYP2C9 *1/*2, and CYP2C19 *1/*17) was prescribed a low dose of the 2D6-metabolized tricyclic antidepressant nortriptyline (12.5 mg/day) 3 days prior to committing homicide. She was severely impaired in metabolizing this drug owing to the 2D6 combination of *4 (null allele) and *41 (reduced activity allele). This subject also had reduced metabolism through 2C9 (*1/*2) and increased (ultrarapid) metabolism through 2C19 (*1/*17), although the significance of these genotypes for nortriptyline metabolism is unclear.

Subject 1, in her own words:

My husband was drinking. I took small doses of valerian for a month and had weird dreams and premonitions. When I took nortriptyline, I immediately wanted to kill myself, talked myself out of it. I’d never had thoughts like that before. My husband was angry, shouting. I walked outside a lot, with palpitations, trouble breathing, and became more depressed. My smoking went up to 25 a day, no alcohol. I didn’t sleep for two nights, dreamt, then slept maybe three hours, felt awful. I dreamt that my daughter had dark teeth and I saw a black halo around her head, a spear hanging over it. I felt like a zombie. I believed I had to help my daughter, that a bad spirit possessed her. I picked up a knife and stabbed her and woke up. I was not myself. I was looking on from the outside, controlled by dark forces. She said: “Mum, what are you doing here?” I realized what I’d done. I asked my husband to kill me. He called the police. I felt better in the police cells without the pills, but the pills started again and thoughts of killing myself returned.

Nortriptyline is extensively metabolized in the liver, primarily by hydroxylation.Citation24,Citation25 There is a strong correlation between total plasma clearance of nortriptyline and 2D6 enzyme activity.Citation25–Citation28 Reduced clearance resulting from this subject’s 2D6 genotype alone would lead to a build up of serum nortriptyline, which has been shown to be associated with loss of efficacy, toxicity, and increased adversity in several studies.Citation29–Citation31 Nortriptyline is also significantly metabolized through 3A4 as an additional pathway, according to in vitroCitation32 and in vivo data.Citation33–Citation36 In the case of severely reduced metabolism through 2D6, as in this subject, 3A4 would have been the major pathway for metabolism. However, the nortriptyline was superimposed on valerian, which has been shown to be a 3A4 inhibitor in vitro and to significantly increase the maximum serum levels of a 3A4 substrate in vivo.Citation37–Citation39 The addition of a substrate to an inhibitor is one drug–drug interaction scenario (Pattern 2), as described in Armstrong et al.Citation40 The addition of nortriptyline to valerian immediately provoked a toxic delirium in this subject; she became akathisic and suicidal and 3 days later she committed the homicide.

Subjects 2, 3, and 4 were prescribed the SSRIs fluoxetine or paroxetine as monotherapy. Both these drugs are metabolized extensively in the liver by 2D6 and these subjects all had variant alleles for 2D6, being either intermediate or poor metabolizers. Fluoxetine and paroxetine are also both potent inhibitors of 2D6, converting both extensive and intermediate metabolizers into poor metabolizers over time.Citation41

Subject 2 (18-year-old male; genotypes: CYP2D6 *4/*5, CYP2C9 *1/*1, and CYP2C19 *1*17), with no CYP2D6 activity due to his carrying a null activity allele (*4) and a gene deletion (*5), was prescribed half the standard dose of fluoxetine, 10 mg/day, for 14 days as his sister was comatose after a car accident. He had used cannabis, whose active ingredients and metabolites have a long half-life. He had normal metabolizing genes for 2C9, which also metabolizes the psychoactive (R)-enantiomer of fluoxetine.Citation42–Citation45 He was an ultrarapid metabolizer for 2C19 (*1/*17). He killed his father 4 days after he ran out of fluoxetine.

Subject 2, in his own words:

I felt better, energized, then restless, no appetite, no sexual desire; gouged my lip then became aggressive, paranoid, violent, could not sleep, walked around thinking constantly about suicide. Tried to kill myself twice, tying a sheet around my neck, cutting my wrist, became depressed, and cried. I ran out of fluoxetine and felt like a ticking time bomb. I had no thoughts for consequences. Fearless, I challenged strangers to fight, punched out windows, threw a toolbox through windscreen and sped, running over street signs, crashed my truck; stood at the top of a bridge wanting to jump. I wrote messages on the shattered windscreen of my vehicle. Wanting to die, I walked a long way to a friend’s house where I found a pistol, walked eight miles to my father’s house, talked to him for a few minutes. Felt very small, as if watching myself from above. I remember my dad, then the sound of a gun. No argument, no provocation. Don’t remember pulling it out of my backpack or pointing it. Couldn’t understand what had happened. What had I done? I wanted to shoot myself. I confessed immediately.

While (S)-fluoxetine is primarily metabolized by 2D6, (R)-fluoxetine is metabolized preferentially by 2C9 and, to a lesser extent, by 2D6.Citation44 In the absence of 2D6 activity, which was the case in this subject, CYPs 2C9, 2C19, and 3A4 would become important metabolic pathways.Citation42–Citation45 The CYP450 metabolic pathways for tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabinol (the major psychoactive ingredients) include 3A4, 2C9, and cannabis inhibits 3A4.Citation46–Citation49 In this subject, the total lack of 2D6 metabolizing capacity, along with interference with other metabolic pathways through the use of cannabis, would have led to rapid increases in fluoxetine serum levels, triggering an akathisic state. He was 18, in an age group now subject to a black box warning in all antidepressant labels. We consider that his age alone placed this subject into the category of persons at increased risk of the adverse events noted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and this was additional to his impaired metabolism of fluoxetine and the use of cannabis. For poor metabolizers, Eli Lilly, in its product information, recommends Prozac® Weekly (Eli Lilly and Co, Indianapolis, IN) capsules, a delayed-release formulation; containing enteric-coated pellets of fluoxetine hydrochloride equivalent to 90 mg (291 μmoles) of fluoxetine.Citation50

Subject 3 (35-year-old male; genotypes CYP2D6 *2/*4, CYP2C9 *1/*2, and CYP2C19 *1/*2) and Subject 4 (46-year-old male; genotypes CYP2D6 *1/*41, CYP2C9 *1/*1, and CYP2C19 *17*17) were on paroxetine. Both subjects were intermediate metabolizers for 2D6, the major metabolic pathway for paroxetine.Citation51,Citation52 Subject 3 had three diminishing mutations across the three CYP genes tested (intermediate metabolizer each of 2D6, 2C9 and 2C19) and was on single dose (20 mg/day), whereas Subject 4 had one diminishing and two ultrarapid mutations and was taking treble dose (60 mg/day). Paroxetine is also known to be an extremely potent inhibitor of 2D6 and has long been known to convert genotypic extensive and intermediate metabolizers to phenotypic poor metabolizers, at steady state.Citation53–Citation55 Over time, these subjects were thereby converted to phenotypic poor metabolizers through the inhibition of 2D6 activity by paroxetine.

Subject 3, a 35-year-old tradesman with one child (genotypes: CYP2D6 *2/*4, CYP2C9 *1/*2, CYP2C19 *1/*2), had diminished metabolizing capacity in all three genes, and was prescribed 20 mg/day paroxetine for relationship difficulties. In his words:

I couldn’t leave my house, had trouble going to work. Anxiety was like nothing I’ve ever had before. Feelings were strange, peculiar, anger unjustified. I felt bad about it. I tried to punch her boyfriend through the car window. Police said I tried to run him down. I thought death was imminent, had an impulse to commit a violent suicide, hoping someone would kill me. I was irritable with family, clients. I had racing thoughts, like a video on fast-forward. Weird, violent dreams, I drove around a lot, sometimes in her street, visiting three or four people in a day, unable to settle. Thought I was bullet-proof, god-like, a special person. My sex drive increased; I had an extraordinary erection, lasting for hours, then I lost interest in everything, stayed in bed, plummeted, depressed, suicidal.

Drove to the park. I did not expect to find them there. My son ran up to me. His mother said, “He’s not going with a crazy person like you.” Last thing I remember was getting the knife from my toolbox, walking in slow motion. A guy cracked a wet towel at me. I reconstructed what happened from what I was told. I got it wrong, for example, where I stabbed her. I knew I had done it because I had blood all over me.

This person committed homicide in a state of automatism following a psychological blow after 11 weeks of akathisia caused by paroxetine toxicity.

Subject 4, an independent and successful businessman, was prescribed paroxetine because he became anxious about the possibility of not making enough money to support his family; he had lost weight and sleep over this. On paroxetine he experienced suicidal urges and stopped it. Later, he resumed taking paroxetine and soon entered a violent manic-suicidal delirium that was accompanied by akathisia. Thinking the drug was not working, he gradually increased the dose to 60 mg/day. His mental condition deteriorated and, 40 days into a homicidal akathisia delirium-like state and affected by a manic shift, he believed that he had to kill his son (to whom he attributed extraordinary powers) and did so, believing he had committed an altruistic, even heroic, act. Like others on psychoactive substances, more so when mood is elevated and cognitive impairment present, he suffered from medication-induced anosognosia, which is defined as “unawareness or denial of a neurological deficit.”Citation56

Subject 5 (16-year-old male; genotypes: CYP2D6 *1/*6, CYP2C9 *1/*1, and CYP2C19 *1/*1) was living in a group home, struggling at school, and his girlfriend had left him. He was prescribed sertraline (unknown dose) and became agitated, described himself as “restless energetic and anxious.” He felt playful at first, and then became “obsessive, impulsive and self-destructive.” He was hospitalized and became uncharacteristically violent, irrational, and compulsive. He began self-mutilating and writing pages of disorientated escape plans, had unwelcome thoughts of destroying property and designing weapons. He felt like he was “caught in whirlwind of feverish, angry and fearful thoughts, losing track of time and having no will power,” and that he was losing his memory. He reported palpitations and tremors on sertraline and experienced violent impulses to hurt himself and others, eventually making a suicide attempt. Sertraline is metabolized mainly by 2C19.Citation57 This subject’s 2C19 alleles were normal, but sertraline immediately provoked in him a range of akathisic behaviors, and this bears further inquiry, given his age and circumstances. Following the attempted suicide, he was switched to fluoxetine, 20 mg/day, and attempted suicide again. After this, fluoxetine was increased first to 40 then 60 mg/day with no improvement in his akathisia. He became emotional and labile and pitted himself against his family and the therapist. Valproate was added and increased to 1000 mg/day. He became agitated then described himself as restless, energetic, and anxious. After 11 weeks in hospital, he killed his therapist and lit a fire.

Valproate inhibits 2C9 in vivo.Citation58 As previously noted, fluoxetine is metabolized by both CYPs 2D6 and 2C9. In this case fluoxetine would be expected to increasingly inhibit his already genetically impaired 2D6 activity, more so as the dose was increased over time. His 2C9 activity would have been inhibited by valproate prescribed at 1000 mg/day. The combined effect of diminished metabolism, to begin with at 2D6, with the inhibition of 2C9 by valproate, would have been to drastically reduce the metabolism of fluoxetine in this subject. The addition of an inhibitor, valproate, to a substrate, fluoxetine, is also a classic drug-interaction scenario (Pattern 1) as described in Armstrong et al.Citation40 In addition to impaired 2D6 metabolism and the addition of valproate, the authors note here again that this subject’s young age would have placed him in the higher risk category for serious adversity on antidepressants, as cautioned by the FDA advisories. This subject recovered fully upon withdrawal of psychiatric drugs.

In only one case, shown in , was the subject an extensive (or normal) metabolizer for the antidepressant drug in use before committing or attempting homicide, but he had been treated with polypharmacy throughout. Subject 6 (50-year-old male; genotypes: CYP2D6 *1/*2, CYP2C9 *1/*1, and CYP2C19 *1/*2) was employed as an administrator and prescribed variously fluoxetine, amitriptyline, diazepam, occasional metoclopramide, and continuously zolpidem or zopiclone for a year to treat distress from his divorce. Fluoxetine was at no time prescribed on its own. He was then prescribed venlafaxine at 300 mg/day, a dose higher than the maximum recommended by the manufacturer Wyeth (Philadelphia, PA),Citation59 (225 mg/day) for 2 years and became more akathisic over this period. He was also put on valproate 1000 mg/day and continued with zolpidem alternating with zopiclone. He was genetically an extensive metabolizer at 2D6 (genotype *1/*2), which metabolizes venlafaxine.Citation60,Citation61 He carried the “null activity” allele 2C19 *2, which may have slowed the metabolism of venlafaxine.Citation62 3A4 is also considered to be important in venlafaxine metabolism.Citation63,Citation64 Taking a friend’s advice, he stopped taking venlafaxine, exchanging it for a vitamin preparation containing serotonin. At the same time, his doctor prescribed the antibiotic ciprofloxacin, which inhibits CYPs 1A2 and 3A4.Citation65,Citation66 At the time of the homicide, he was taking ciprofloxacin, valproate, and the vitamin mixture containing serotonin, as well as dosing repeatedly with zolpidem. While sleep driving, and after cleaning a friend’s gun, he shot two strangers. As in other cases of aberrant sleep behaviors associated with zolpidem, he remembered none of this time period. While the subject’s venlafaxine, serotonin, or zolpidem levels during the venlafaxine withdrawal and subsequent homicide cannot be known, it has been shown that zolpidem and venlafaxine (along with other serotonin-boosting drugs) interact leading to serotonin syndrome, a myriad of mental state changes and hallucinatory states.Citation67 Ciprofloxacin, which inhibits the major metabolic pathway of zolpidem, 3A4, would further have increased the level of zolpidem as these also interact pharmacokinetically, with an estimated 46% increase in bioavailability of zolpidem.Citation68 The subject suffered the zolpidem side effect of sleep activity, while serotonin toxicity is associated with violence. His treating doctors kept him taking antidepressants for some years. He stopped taking medication in prison, whereupon he returned to his normal personality.

While all the subjects had variant alleles and diminished CYP450 metabolism, subjects 7, 8, 9, and 10 all had variant alleles in the major pathways for the antidepressants they were taking while they were experiencing violent episodes, which, in these cases, involved attempted homicide. Furthermore, they were also using, alone or in combination, either other medications, illicit substances, or herbal remedies that had the combined effect of exacerbating the impaired metabolism caused by their variant alleles.

Subject 7 (25-year-old male; genotypes: CYP2D6 *1/*41, CYP2C9 *1/*2, and CYP2C19 *1/*2) was prescribed 10 mg escitalopram (double the standard dose) for anxiety following the birth of his child and to help him stop illicit substance use (which may have included cannabis). He was also on hypericum 900 mg/day. Escitalopram, the (S)-enantiomer of citalopram, has been shown to be the most selective of the SSRIs and at least 30 fold more potent than its (R)-isomer, based on in vitro studies.Citation69 Escitalopram is demethylated by CYPs 2C19, 3A4, and 2D6 to (S)-desmethylcitalopram and then demethylated further, at a much slower rate, by 2D6 to (S)-didesmethylcitalopram, which are both psychoactive.Citation1,Citation70,Citation71 The relative contributions to net intrinsic clearance of escit-alopram from in vitro data, after correction for relative hepatic abundance, have been estimated as: 2C19 (37%), 3A4 (35%), and 2D6 (28%).Citation72 In keeping with this, escitalopram interacts clinically with both 3A4 and 2D6 substrates. This subject had an inactive 2C19 allele (*2) and a reduced-function allele for 2D6 (*41) and 3A4 is induced by hypericum over time.Citation73 He reported that his personality changed in that he immediately became depressed, suicidal, agitated, paranoid, and very aggressive, he also felt “manic,” impulsive, and despairing and complained of ejaculation failure. Starting on the sixth day after commencing escitalopram, he made several suicide attempts and several assaults on his partner over 40 days, the last causing her near-lethal injuries. The effects of the cumulative dose of a serotonin reuptake blocker, escitalopram, in combination with hypericum at high dose were synergistic on serotonin levels and immediately caused violent serotonin toxicity, which overlaps and coexists with akathisia.Citation74

Subject 8, a mother (26-year-old-female; genotypes: CYP2D6 *2/*4, CYP2C9 *1/*1, CYP2C19 *2/*17), was initially prescribed paroxetine for stress. On paroxetine, she experienced an uncharacteristic episode of rage and attempted suicide by inhalation of carbon monoxide from a car exhaust, so she stopped taking it. Two years later, she was prescribed paroxetine again and reassured about its safety. The second time she experienced intense restlessness, surges of rage and anger, marital troubles, panic attacks, impulsive spending sprees, and constant suicidal ideation. She reasoned that her low self-esteem, insomnia, and suicidal behavior were due to difficulties with her in-laws. She overdosed and was admitted to hospital where paroxetine was increased. She tried to kill herself again and was diagnosed with an “adjustment disorder,” a stress-induced state. She was switched to venlafaxine, 37.5 mg/day and it was increased to 300 mg/day over 3 months. Each upward dose adjustment occasioned a week spent in bed with exhaustion, as she was unable to get up (akinesia). Her mental state deteriorated and violent outbursts and suicidal ideation became frequent and severe. Unable to stay in one place, she drove several hundred miles with her children and tried to kill them and herself by car exhaust. A few days later she tried to kill her children and herself again. There were no interacting drugs in her regimen, however, her genotype for 2D6 (*2/*4) places her in the intermediate metabolizer category, for which there is evidence of at least twofold increases in serum-venlafaxine levels in both single dose and steady-state studies.Citation75–Citation77 Moreover, case reports have documented serious venlafaxine-related adverse events, which are either suspected or confirmed to have resulted from above-therapeutic-range serum-venlafaxine levels; the events ranged from psychosisCitation78,Citation79 to hallucination, psychomotor agitation, and delirium.Citation80–Citation82

The subject pleaded diminished responsibility to four charges of attempted murder and was not required to complete time in prison. She recovered fully on withdrawal.

Wyeth has provided the following information in product information for venlafaxine, Effexor® XR, including homicidal ideation, since 2005.Citation59 (Note: frequent is 1/10; infrequent, 1/100; rare, 1/1000; suicide attempts and homicidal thinking are catastrophic effects, irrespective of frequency.)

Body as a whole – Frequent: chest pain substernal, chills, fever, neck pain; Infrequent: face edema, intentional injury, malaise, moniliasis, neck rigidity, pelvic pain, photosensitivity reaction, suicide attempt, withdrawal syndrome; Rare: appendicitis, bacteremia, carcinoma, cellulitis.

Nervous system – Frequent: amnesia, confusion, depersonalization, hypesthesia, thinking abnormal, trismus, vertigo; Infrequent: akathisia, apathy, ataxia, circumoral paresthesia, CNS stimulation, emotional lability, euphoria, hallucinations, hostility, hyperesthesia, hyperkinesia, hypotonia, incoordination, manic reaction, myoclonus, neuralgia, neuropathy, psychosis, seizure, abnormal speech, stupor, suicidal ideation; Rare: abnormal/changed behavior, adjustment disorder, akinesia, alcohol abuse, aphasia, bradykinesia, buccoglossal syndrome, cerebrovascular accident, feeling drunk, loss of consciousness, delusions, dementia, dystonia, energy increased, facial paralysis, abnormal gait, Guillain-Barre Syndrome, homicidal ideation, hyperchlorhydria, hypokinesia, hysteria, impulse control difficulties, libido increased, motion sickness, neuritis, nystagmus, paranoid reaction, paresis, psychotic depression, reflexes decreased, reflexes increased, torticollis.

Very little of the above-quoted information appears in Australian product information for Efexor®. It contains no black box warning, denies differences in metabolism between poor and extensive metabolizers, and lists only for nervous system:

Common: Abnormal dreams, decreased libido, dizziness, dry mouth, increased muscle tonus, insomnia, nervousness, paraesthesia, sedation, tremor. Uncommon: Apathy, hallucinations, myoclonus. Rare: Convulsion, manic reaction, neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), serotonergic syndrome.Citation83

Subject 9 (52-year-old female; genotypes: CYP2D6 *4/*4, CYP2C9 *1/*1, and CYP2C19 *1/*1), a teacher, was prescribed a series of antidepressants following harassment at work. After 3 years on a series of antidepressants, always superimposed on polypharmacy containing CYP450 substrates and inhibitors and drugs with similar side effects and causative of pharmacodynamic interactions, she tried to kill her two children while taking venlafaxine with other medicines. She suffered from mild chronic bilirubinemia, which may have been Gilbert’s syndrome.

She was suffering from stress at work and paroxetine was prescribed and increased to 60 mg/day. Paroxetine is metabolized by 2D6 and she had no 2D6 activity, with two null alleles (*4/*4). After paroxetine had occasioned a hospital admission for suicidality, she was switched to citalopram and this was titrated up to 60 mg/day, which was three times the standard dose, while her restlessness, aggression, and suicidality continued. Citalopram is metabolized by CYPs 2C19, 2D6, and 3A4.Citation1,Citation84,Citation85 Its major metabolic pathway, 2C19, was inhibited by her treatment for menopause, conjugated estrogens, which also inhibit CYPs 3A4 and 2C19, as do naturally occurring estrogens.Citation1 Citalopram was replaced by venlafaxine, which is metabolized by CYPs 2D6, 2C9, and 2C19, and inhibits 2D6 mildly, but it was prescribed at 300 mg/day, eight times the standard dose. Her body pain, diagnosed as “atypical somatoform disorder” occasioned the use of tramadol, metabolized by 2D6, and celecoxib, which is metabolized by 2C9 and inhibits 2D6.Citation86–Citation88 Her hypertension was treated with irbesartan, metabolized by 2C9.Citation89 Her elevated cholesterol was treated with atorvastatin, metabolized by 3A4 and inhibits 2C9 and 3A4, and this drug is associated with painful muscle degeneration.Citation1,Citation90 Tramadol and celecoxib interact adversely.

Irregular doses of the akathisia-inducing and 2D6-metabolized drugs metoclopramide and tramadol, which can cause serotonin syndrome, made it impossible for her to recall exactly which of these two co-prescribed drugs she had taken prior to attempting to kill her children and herself, first by gas and then by almost jumping with them from a great height, an impulse she resisted at the last minute. She had been hospitalized eleven times over 3 years for suicidal behaviors and for the homicide attempts, but she no longer needed psychiatric attention after she stopped taking medicines.

She came to the first author’s attention a year after the homicide attempts as she had been charged with “entering enclosed lands,” while delirious after missing doses of venlafaxine, which were left at home over a holiday weekend. She returned to work briefly after following withdrawal protocols from the Internet, but further prescriptions of lovastatin, tramadol, and estrogens all induced further bouts of akathisia and she lost her job. She was never “herself ” again or able to work, but hypertension did resolve. She reported this:

I’m more depressed than I’ve ever been in my life. I throw things when someone comes into my room. I had surges of rage with everyone, with the medical people who could not fix me. It was strange to feel like that, with violent thoughts all the time. I drove all day to find a silo I was going to jump. I took the children on a holiday and gassed us all to kill them and myself. I was not charged. The thoughts of suicide are there all the time. I’ve now started a suicide book. The psychiatrist doesn’t understand me. I fidget, cannot keep my legs still, I am apprehensive, irritable, uncomfortable with unstable mood. I’ve got a hit list in my head. It’s listed, one, two, three. I think how to get access to these people. I feel violent. Before all this, I was a big reader. I can’t focus.

Subject 10 (25-year-old female; genotypes: CYP2D6 *2/*4, CYP2C9 *1/*3, and CYP2C19 *1/*1) was in an abusive relationship, using cannabis, and was prescribed citalopram, unknown dose. She immediately became very disturbed, aggressive, and made multiple suicide attempts. She tried to jump in front of a train with her child and lost custody as a result. Her medication was changed to venlafaxine to treat her worsening depression. More of the same disturbed behavior followed and went on for several years. She was prescribed diazepam and other benzodiazepines to counteract her akathisia and it was then alleged that she was addicted to them. Cannabis use continued throughout. She recalled having constant thoughts of self-harm, and was being told she was “attention seeking” when she was arrested for running in front of a car in one of her many suicide attempts. She subsequently made a good recovery after slowly stopping the venlafaxine. In this case, venlafaxine metabolism would have been severely diminished due to her 2D6 genotype (*2/*4) and the alternative pathways, 2C19 and 3A4, would also have been compromised through the combination of 2C19 genotype (*1/*3) and the inhibition of 3A4 by components of cannabis.

Discussion

In all of the cases presented here, the subjects were prescribed antidepressants that failed to mitigate distress emerging from their predicaments, which encompassed psychosocial stressors such as bereavement, marital and relationship difficulties, and work-related stress. Every subject’s emotional reaction worsened while their prescribing physicians continued the “trial and error” approach, increasing from standard to higher dose and/or switching to other antidepressants, with disastrous consequences. In some cases the violence ensued from changes occasioned by withdrawal and polypharmacy. In all of these cases, the subjects were put into a state of drug-induced toxicity manifesting as akathisia, which resolved only upon discontinuation of the antidepressant drugs.

This paper has detailed and substantiated in specific terms how the metabolism of each of the antidepressant drugs used by the subjects would have been seriously impaired both before and at the time they committed or attempted homicide. They were experiencing severe reported side effects, adverse drug reactions due to impaired metabolism complicated by drug–drug interactions against a background of variant CYP450 alleles. It is important to consider that, while the literature often reports on “major” pathways of metabolism based on studies including subjects with known polymorphisms, “minor” pathways can become more important in certain circumstances, such as when major pathways are unavailable due to inhibition or genetic impairment. In addition, in some cases, psychoactive metabolites have different metabolic pathways that warrant investigation. It also bears mentioning here that CYP2C19 *17 occurred in 28/85 akathisia subjects and in four of the more severe cases, including one homozygous *17/*17, which are detailed in . A previous meta-analysis concluded that this particular allele is likely to have limited clinical impact, however, the results reported here point to the possibility of it having a role in some of the severe adversity occasioned by the prescribing regimes, as detailed in .Citation91 Notably, CYP2C19 *17 has been previously cited as potentially being problematic for antidepressant therapy.Citation12 In all the cases in where a 2C19 *17 was present, 2D6 also had genetically impaired metabolic capacity and this combination of ultrarapid for 2C19 and diminished for 2D6 bears further investigation into its impact on metabolism of psychiatric medications.

Healy’s evidence in a series of Daubert hearings concerning antidepressant-induced akathisia homicide cases was substantiated by documents obtained through court-ordered access to drug companies’ archives.Citation92,Citation93 Akathisia suicides and homicides, particularly when they involved children, gave rise to the first antidepressant suicide advisories in 2003, amid a public outcry. Healy published the watershed review in 2003 “Lines of evidence on the risks of suicide with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).” Citation94 This challenged but did not arrest the ongoing denial by their manufacturers in the USA. Healy concluded

[t]he data reviewed here, which indicate a possible doubling of the relative risk of both suicides and suicide attempts on SSRIs compared with older antidepressants or non-treatment, make it difficult to sustain a null hypothesis, ie, that SSRIs do not cause problems in some individuals to whom they are given. Further studies or further access to data are indicated to establish the magnitude of any risk and the characteristics of patients who may be most at risk.Citation94

The FDA was aware of successful litigation based on suicide epidemiology and, having held some public hearings, it further ordered that a black box warning about the effects of SSRIs in children, part of a “class suicidality labelling language for antidepressants,” be incorporated in each drug’s product information.Citation95 The first advisory concerning adults was posted on March 22, 2004. It warned of, among other conditions and side effects, “worsening depression or the emergence of suicidality” and “hostility, aggressiveness, impulsivity, akathisia” in both “adult and pediatric patients being treated with antidepressants for major depressive disorder as well as for other indications, both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric.”Citation96

In June 2005, the FDA conceded “causation” of suicide by antidepressants in that relative risk of suicide vs untreated was doubled or more. The FDA later extended suicide warnings to other medicines. In 2006, it reviewed 273 clinical trials but ignored suicides committed in the withdrawal period, which it still refers to and counts as “placebo suicides.”Citation95 By the criteria used by the FDA, the two homicides committed 2 and 4 days into withdrawal by Subjects 2 and 6 would not be counted as SSRI events, as FDA calculations only count suicides on active substance or 1 day after stopping. These advisories and their history are published on the website of the FDA.Citation96

Deteriorating outcomes in mental illness, deaths, violence, and suicide rates have been documented by epidemiologists and have increased up to 20-fold since 1924.Citation97–Citation101 Some people taking psychiatric drugs develop akathisia and some people who develop akathisia kill themselves or others. Yet the drugs can be effective in persons suffering serious depression, provided their doses are adjusted according to their ability to metabolize them normally and there is informed monitoring.

Australian prescribers and patients have still not been advised of antidepressant suicide or homicide by relevant authorities, including the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). The TGA did not follow or adopt any of the public health advisories produced by the FDA, nor did it demand that drug companies notify users or prescribers of these major changes. Further, drug companies were not forced to include the “class suicidality labelling language for antidepressants” in full or accurately, in Australian prescribing information. Australian institutions; health departments, both state and federal; medical boards; medical students; courts and coroners; and colleges are still being advised that the notion that an antidepressant induces suicide or homicide is a strange idea (Yolande Lucire, personal experience). The result of this lack of knowledge has been a trebling of demand for mental heath services, paralleled by rising costs since 1990, rising numbers of nonrecovering patients and of suicides and homicides by patients under mental health care.Citation102 Failing to make clear that these effects are not related to the psychiatric diagnosis, are not evidence of bipolar mania, schizophrenia, or major depression, the criteria for which stipulate an exclusion that the diagnosis to be made is not caused by a substance, a medication, or other treatmentCitation103 causes some Australian prescribers to believe they are seeing an exacerbation of a psychiatric condition or a new disorder. Akathisia, a toxidrome, is a neurotoxic side effect, sometimes accompanied by a delirium, reported as a disjointed narrative resembling a natural dream. It is entirely different from a functional psychosis that manifests in a clear sensorium, often associated with delusions that rationalize the hallucinations. Census data from 2001 indicated that 4.7% of Australians were on or had recently used antidepressants and a total of 9.6% were similarly using psychotropic medications.Citation104 Olfson and Marcus reported that, in 2005, 1/10 Americans over the age of 6 was on antidepressant medication and these people were more likely be given antipsychotic medications as well.Citation105

The authors believe that they have identified some of the major problems that underpin adversity and akathisia induced by improper dosing of antidepressants. Attending to these through careful consideration of the published evidence on diagnosis and treatment using pharmacogenetic information and consideration of drug interactions can help reverse this public health catastrophe. The authors consider that public health advisories warning of the effects of interactions between illicit substances and medications may also be warranted.

Medication-induced suicide and homicide

Drugs as diverse in structure and function as hypericum (St John’s wort),Citation106 varenicline (Chantix®; Pfizer, New York, NY), oseltamivir (Tamiflu®; Genentech USA, Inc, San Francisco, CA), isotretinoin (Roaccutane®; Hoffman-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland), mefloquine (Lariam®; Hoffman-La Roache), metoclopramide (Maxolon®; Shire plc, St Helier, Jersey, UK; Reglan®; UCB, Brussels, Belgium), zolpidem (Stilnox®; Sanofi-Aventis, Paris, France;) calcium channel blockers, antiepileptic drugs mooted as “mood stabilizers,” reserpine, benzodiazepines, statins, and interferon,Citation107 all induce suicidal and homicidal thinking as an occasional side effect. Moore et al (2010) identified 1527 cases of violence, including homicides, disproportionally reported to the FDA for 31 drugs, including varenicline, eleven antidepressants, six sedative/hypnotics and three drugs for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.Citation108

Akathisia has been known to be associated with suicide since the 1950s and with homicide since 1985.Citation109,Citation110 Shear et al (1983) reported homicides associated with akathisia after treatment with depot fluphenazine.Citation111 Schulte (1985) described cases of suicide and homicide associated with haloperidol.Citation112 Healy et al (2006) described nine cases of murder, suicide, and severe violence in patients who had not been mentally ill before being medicated.Citation113 Meysenburg and Bostock, pharmacovigilantes, have collated information obtained from over 4600 media stories of massacres, homicides, suicides, and school and college shootings dating back to 1966, involving antidepressants old and new, and drugs prescribed for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, detailing the drugs and legal defences in some cases.Citation114

In the cases presented in this paper, concerning subjects with abnormal CYP450 metabolism (ie, ultrarapid and/or diminished), the antidepressant or its metabolites may have reached a toxic level in hours or days correlating with onset of intense dysphoria and akathisia. The symptoms of toxicity were not recognized, or were ignored by patient and/or treating doctor and, in many cases, the dose of the antidepressant was increased while various “antidotes” to side effects, like sleeping pills, nausea, and pain medications, were added. They were prescribed by clinicians educated by drug company representatives, available information, and key opinion leaders who receive substantial benefits from the makers of these drugs, an issue that is coming to light with whistle-blower (qui tam) cases taken by attorneys, state and federal, against the makers for fraudulent promotion.Citation115 Healy (2006) has documented the details of these fraudulent promotions, but they remain outside the purview of regulatory agencies who approve, even subsidise, drugs and sanction ghost-written product information concerning their use.Citation116

Conclusion

A detailed history and mental-state examination in these subjects presented here can exclude functional mental illness (which still has no biological markers) and confirm neurotoxicity. Pharmacogenetic evidence can assist with the rediagnosis of the population that causes the increased demand for mental health services. Restoring them to normality will reduce that demand and associated costs by taking pressure off ambulances, hospitals, prisons, and forensic wards.

Akathisia homicides have been defended as instances of involuntary intoxication both with and without genetic evidence.Citation114,Citation117,Citation118 Some perpetrators (and victims) succeed in receiving damages from the manufacturers for failure to warn.Citation119 The Innocence Project examined evidence from crimes that took place before DNA testing was available.Citation120 Personalized medicine in health care can bring about corresponding personalized justice in clinics, tribunals, courts and morgues.Citation121

The most basic textbook of psychiatry, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, appended with each new edition’s number, provides this Delphic, obscure, and ambiguous guidance about treating akathisia: “Worsening of psychotic symptoms or behavioral dyscontrol may lead to an increase in neuroleptic medication dose, which may exacerbate the problem.” Differentiating akathisia (a toxic psychosis) from schizophrenia would be a crucial differential diagnosis in psychiatry in that the appropriate treatment for one condition can be catastrophic for another. Akathisia can develop very rapidly after initiating or increasing neuroleptic medication.Citation103

However, sudden (as opposed to slow) withdrawal of serotonin-boosting antidepressants (or other substances) in an akathisia sufferer may make the problem worse and staying on them, once akathisia has developed, is equally dangerous. It is the authors’ contention that prescribing antidepressants without knowing about CYP450 genotypes is like giving blood transfusions without matching for ABO groups. Similarly, it is essential that other drugs in a patient’s drug regimen be understood in terms of interacting with CYP450 enzymes as substrates, inducers, or inhibitors.

In 2010, Piggott et al reviewed meta-analyses of efficacy trials and the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study. They found that antidepressants were only marginally (2.7%) more efficacious compared with placebos. The same meta-analyses documented profound publication bias, inflating their apparent efficacy as well as bias in failing to report the negative results. The STAR*D analysis found that the effectiveness of antidepressant therapies was probably even lower than the modest one reported by the study authors with a progressively increasing dropout rate across each study phase. The authors argue for a reappraisal of the current recommended standard of care of depression.Citation122

Acknowledgements

Thanks are extended to Healthscope Molecular in Clayton, Victoria, and Diversity Health Institute, Westmead Hospital, Westmead, New South Wales, Australia, for generosity in providing genetic testing.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WynnGHOesterheldJRCozzaKArmstrongSCClinical Manual of Drug Interaction Principles for Medical PracticeArlington, VAAmerican Psychiatric Publishing2009

- LicinioJWongMLThe pharmacogenomics of depressionPharmacogenomics J200113175177 Review11908753

- BertilssonIDahlM-LTybringGPharmacogenetics of antidepressants: clinical aspectsActa Psychiatr Scand Suppl19973911421 Review9265947

- The Human Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Allele Nomenclature Committee [homepage on the Internet]StockholmKarolinska group [updated 2008 Sep]. Available from: http://www.cypalleles.ki.se. Accessed May 23, 2011

- Ingelman-SundbergMSimSCPharmacogenetic biomarkers as tools for improved drug therapy; emphasis on the cytochrome P450 systemBiochem Biophys Res Commun521201039619094 Review20494117

- de LeonJArmstrongSCCozzaKLClinical guidelines for using pharmacogenetic testing of CYP450 2D6 and CYP450 2C19 in psychiatryPsychosomatics200647758516384813

- ZourkováAHadasováEParoxetine-induced conversion of cytochrome P450 2D6 phenotype and occurence of adverse effectsGen Physiol Biophys20032210311312870705

- GascheYDaaliYFathiMCodeine intoxication associated with ultrarapid CYP2D6 metabolismN Engl J Med20043512827283115625333

- ZackrissonALLindblomBAhlnerJHigh frequency of occurrence of CYP2D6 gene duplication/multiduplication indicating ultrarapid metabolism among suicide casesClin Pharmacol Ther201088335435919907421

- ZackrissonALHolmgrenPGladhABAhlnerJLindblomBFatal intoxication cases: cytochrome P450 2D6 and 2C19 genotype distributionsEur J Clin Pharmacol200460854755215349706

- ZackrissonALHolmgrenPGladhABAhlnerJLindblomBCytochrome P450 2D6 genotyping of fatal intoxications using PyrosequencingProgress in Forensic Genetics 10200412613638

- SimSCRisingerCDahlMLA common novel CYP2C19 gene variant causes ultrarapid drug metabolism relevant for the drug response to proton pump inhibitors andantidepressantsClin Pharmacol Ther200679110311316413245

- SachdevPThe epidemiology of drug-induced akathisia: part I. Acute akathisiaSchizophr Bull1995213431449 Review7481574

- SachdevPThe epidemiology of drug-induced akathisia: part II. Chronic, tardive, and withdrawal akathisiasSchizophr Bull1995213451461 Review7481575

- US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Drugs@FDAFDA approved drug products [webpage on the Internet]Silver Spring, MDFDA [nd]. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm. Accessed April 28, 2011

- VandelPHaffenEVandelSDrug extrapyramidal side effects. CYP2D6 genotypes and phenotypesEur J Clin Pharmacol199955965966510638395

- Indiana University School of Medicine Department of Medicine, Division of Clinical Pharmacology. Drug Interactions: cytochrome P450 drug interaction table [website on the Internet]Indianapolis, INIndiana University School of Medicine2011 [updated April 12, 2011]. Available from: http://medicine.iupui.edu/clinpharm/ddis/table.asp Accessed April 12, 2011

- BaumannPHiemkeCUlrichSThe AGNP-TDM expert group consensus guidelines: therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatryPharmacopsychiatry200437624326515551191

- BregginPRSuicidality, violence and mania caused by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): a review and analysisInt J Risk Saf Med20031613149

- LargeMSharmaSComptonMTSladeTNielssenOCannabis use and earlier onset of psychosis: a systematic meta-analysisArch Gen Psychiatry Epub February 7, 2011

- PiatkovIJonesTRochesterCCytochrome P450 loss-of-function polymorphism genotyping on the Agilent Bioanalyzer and clinical applicationPharmacogenomics200910121987199419958097

- Pers comm; Keith Byron, 2011

- GaedigkASimonSDPearceREBradfordLDKennedyMJLeederJSThe CYP2D6 activity score: translating genotype information into a qualitative measure of phenotypeClin Pharmacol Ther200883223424217971818

- SjöqvistFAlexandersonBAsbergMPharmacokinetics and biological effects of nortriptyline in manActa Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh)197129Suppl 32552805316407

- BertilssonLEichelbaumMMellströmBSäweJSchulzHUSjöqvistFNortriptyline and antipyrine clearance in relation to debrisoquine hydroxylation in manLife Sci19802718167316777442467

- MellströmBBertilssonLSäweJSchulzHUSjöqvistFE- and Z-10-hydroxylation of nortriptyline: relationship to polymorphic debrisoquine hydroxylationClin Pharmacol Ther19813021891937249504

- von BahrCBirgerssonCBlanckAGöranssonMMellströmBNilsellKCorrelation between nortriptyline and debrisoquine hydroxylation in the human liverLife Sci19833376316366410141

- DahlMLNordinCBertilssonLEnantioselective hydroxylation of nortriptyline in human liver microsomes, intestinal homogenate, and patients treated with nortriptylineTher Drug Monit19911331891941926270

- KinNMKlitgaardNNairNPClinical relevance of serum nortriptyline and 10-hydroxy-nortriptyline measurements in the depressed elderly: a multicenter pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studyNeuro Psychopharmacology199615116

- PerryPJZeilmannCArndtSTricyclic antidepressant concentrations in plasma: an estimate of their sensitivity and specificity as a predictor of responseJ Clin Psychopharmacol1994144230240 Review7962678

- SteimerWZöpfKvon AmelunxenSAmitriptyline or not, that is the question: pharmacogenetic testing of CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 identifies patients with low or high risk for side effects in amitriptyline therapyClin Chem200551237638515590749

- VenkatakrishnanKvon MoltkeLLGreenblattDJNortriptyline E-10-hydroxylation in vitro is mediated by human CYP2D6 (high affinity) and CYP3A4 (low affinity): implications for interactions with enzyme-inducing drugsJ Clin Pharmacol1999396567577 Erratum in: J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;39(8):86610354960

- BrøsenKKragh-SørensenPConcomitant intake of nortriptyline and carbamazepineTher Drug Monit19931532582608333008

- KrähenbühlSSmith-GambleVHoppelCLPharmacokinetic interaction between diltiazem and nortriptylineEur J Clin Pharmacol19964954174198866640

- GannonRHAndersonMLFluconazole-nortriptyline drug interactionAnn Pharmacother19922611145614571477454

- BebchukJMStewartDEDrug interaction between rifampin and nortriptyline: a case reportInt J Psychiatry Med19912121831871894457

- ZhouSGaoYJiangWHuangMXuAPaxtonJWInteractions of herbs with cytochrome P450Drug Metab Rev2003351359812635815

- LefebvreTFosterBCDrouinCEKrantisALiveseyJFJordanSAIn vitro activity of commercial valerian root extracts against human cytochrome P450 3A4J Pharm Pharm Sci200412 7(2)26527315367385

- DonovanJLDeVaneCLChavinKDMultiple night-time doses of valerian (Valeriana officinalis) had minimal effects on CYP3A4 activity and no effect on CYP2D6 activity in healthy volunteersDrug Metab Dispos200432121333133615328251

- ArmstrongSCCozzaKLSandsonNBSix Patterns of drug-drug interactionsPsychosomatics200344325525812724509

- SpinaESantoroVD’ArrigoCClinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with second-generation antidepressants: an updateClin Ther200830712061227 Review18691982

- MargolisJMO’DonnellJPMankowskiDCEkinsSObachRS(R)-, (S)-, and racemic fluoxetine N-demethylation by human cytochrome P450 enzymesDrug Metab Dispos200028101187119110997938

- ScordoMGSpinaEDahlMLGattiGPeruccaEInfluence of CYP2C9, 2C19 and 2D6 genetic polymorphisms on the steady-state plasma concentrations of the enantiomers of fluoxetine and norfluoxetineBas Clin Pharmacol Toxicol2005975296301

- RingBJEcksteinJAGillespieJSBinkleySNVandenBrandenMWrightonSAIdentification of the human cytochromes p450 responsible for in vitro formation of R- and S-norfluoxetineJ Pharmacol Exp Ther200129731044105011356927

- FjordsideLJeppesenUEapCBPowellKBaumannPBrøsenKThestereoselective metabolism of fluoxetine in poor and extensive metabolizers of sparteinePharmacogenetics199991556010208643

- YamaoriSEbisawaJOkushimaYYamamotoIWatanabeKPotent inhibition of human cytochrome P450 3A isoforms by cannabidiol: role of phenolic hydroxyl groups in the resorcinol moietyLife Sci201111 88(15–16)730736 Epub February 26, 201121356216

- Sachse-SeebothCPfeilJSehrtDInterindividual variation in the pharmacokinetics of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol as related to genetic polymorphisms in CYP2C9Clin Pharmacol Ther2009853273276 Epub November 12, 200819005461

- WatanabeKYamaoriSFunahashiTKimuraTYamamotoICytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of tetrahydrocannabinols and cannabinol by human hepatic microsomesLife Sci200720801514151419 Epub January 17, 200717303175

- BlandTMHainingRLTracyTSCalleryPSCYP2C-catalyzed delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol metabolism: kinetics, pharmacogenetics and interaction with phenytoinBiochem Pharmacol20051 70(7)1096110316112652

- Eli Lilly and CoProzac Weekly® [product information]IndianapolisEli Lilly and Co2001 Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2001/21-235_Prozac_Prntlbl.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2011

- SawamuraKSuzukiYSomeyaTEffects of dosage and CYP2D6-mutated allele on plasma concentration of paroxetineEur J Clin Pharmacol2004608553557 Epub September 3, 200415349705

- CharlierCBrolyFLhermitteMPintoEAnsseauMPlomteuxGPolymorphisms in the CYP 2D6 gene: association with plasma concentrations of fluoxetine and paroxetineTher Drug Monit200325673874214639062

- SindrupSHBrøsenKGramLFThe relationship between paroxetine and the sparteine oxidation polymorphismClin Pharmacol Ther19925132782871531950

- JeppesenUGramLFVistisenKLoftSPoulsenHEBrøsenKDose-dependent inhibition of CYP1A2, CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 by citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and paroxetineEur J Clin Pharmacol199651173788880055

- SindrupSHBrøsenKGramLFPharmacokinetics of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine: nonlinearity and relation to the sparteine oxidation polymorphismClin Pharmacol Ther19925132882951531951

- BregginPRIntoxication anosognosia: the spellbinding effect of psychiatric drugsEthical Hum Psychol Psychiatry200683201205

- RudbergIHermannMRefsumHMoldenESerum concentrations of sertraline and N-desmethyl sertraline in relation to CYP2C19 genotype in psychiatric patientsEur J Clin Pharmacol2008641211811188 Epub August 3, 200818677622

- GunesABilirEZengilHBabaogluMOBozkurtAYasarUInhibitory effect of valproic acid on cytochrome P450 2C9 activity in epilepsy patientsBas Clin Pharmacol Toxicol20071006383386

- Wyeth Pharmaceuticals IncEffexor XR® [product information]Philadelphia, PAWyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc2005 Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2005/020699s054,057lbl.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2011

- HermannMHendsetMFosaasKHjerpsetMRefsumHSerum concentrations of venlafaxine and its metabolites O-desmethylvenlafaxine and N-desmethylvenlafaxine in heterozygous carriers of the CYP2D6*3, *4 or *5 alleleEur J Clin Pharmacol2008645483487 Epub January 23, 200818214456

- ShamsMEArnethBHiemkeCCYP2D6 polymorphism and clinical effect of the antidepressant venlafaxineJ Clin Pharmacol Ther2006315493502

- FukudaTNishidaYZhouQYamamotoIKondoSAzumaJThe impact of the CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes on venlafaxine pharmacokinetics in a Japanese populationEur J Clin Pharmacol200056217518010877013

- LindhJDAnnasAMeurlingLDahlMLAL-ShurbajiAEffect of ketoconazole on venlafaxine plasma concentrations in extensive and poor metabolisers of debrisoquineEur J Clin Pharmacol2003595–6401406 Epub July 25, 200312898080

- FogelmanSMSchmiderJVenkatakrishnanKO- and N-demethylation of venlafaxine in vitro by human liver microsomes and by microsomes from cDNA-transfected cells: effect of metabolic inhibitors and SSRI antidepressantsNeuro psychopharmacology1999205480490

- SriwiriyajanSSamaengMRidtitidWMahatthanatrakulWWongnawaMPharmacokinetic interactions between ciprofloxacin and itraconazole in healthy male volunteersBiopharm Drug Dis2011323168174 Epub March 1, 2011.

- ShahzadiAJavedIAslamBTherapeutic effects of ciprofloxacin on the pharmacokinetics of carbamazepine in healthy adult male volunteersPak J Pharm Sci2011241636821190921

- ElkoCJBurgessJLRobertsonWOZolpidem-associated hallucinations and serotonin reuptake inhibition: a possible interactionJ Toxicol Clin Toxicol1998363195203 Review9656974

- VlaseLPopaANeagMMunteanDLeucutaSEPharmacokinetic interaction between zolpidem and ciprofloxacin in healthy volunteersEur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet2011353–48387 Epub October 5, 2010.21302033

- OwensMJKnightDLNemeroffCBSecond-generation SSRIs: human monoamine transporter binding profile of escitalopram and R-fluoxetineEur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet2001505345350

- OlesenOVLinnetKStudies on the stereoselective metabolism of citalopram by human liver microsomes and cDNA-expressed cytochrome P450 enzymesPharmacology199959629830910575324

- HerrlinKYasui-FurukoriNTybringGWidénJGustafssonLLBertilssonLMetabolism of citalopram enantiomers in CYP2C19/CYP2D6 phenotyped panels of healthy SwedesBritish J Clin Pharmacol2003564415421

- von MoltkeLLGreenblattDJGiancarloGMGrandaBWHarmatzJSShaderRIEscitalopram (S-citalopram) and its metabolites in vitro: cytochromes mediating biotransformation, inhibitory effects, and comparison to R-citalopramDrug Metab Dispos20012981102110911454728

- MannelMDrug interactions with St John’s wort: mechanisms and clinical implicationsDrug Saf20042711773797 Review15350151

- RobinsonDSSerotonin SyndromePrimary Psychiatry20061383638

- FukudaTYamamotoINishidaYEffect of the CYP2D6*10 genotype on venlafaxine pharmacokinetics in healthy adult volunteersBr J Clin Pharmacol199947445045310233212

- FukudaTNishidaYZhouQYamamotoIKondoSAzumaJThe impact of the CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes on venlafaxine pharmacokinetics in a Japanese populationEur J Clin Pharmacol20005562:1758010877013

- VeefkindAHHaffmansPMHoencampEVenlafaxine serum levels and CYP2D6 genotypeTher Drug Monit200022220220810774634

- SafeekhATPintoDVenlafaxine-induced psychotic symptomsIndian J Psychiatry200951430830920048460

- PfefferFGrubeMAn organic psychosis due to a venlafaxine-propafenone interactionInt J Psychiatry Med200131442743211949740

- GareriPDe FazioPGallelliLVenlafaxine-propafenone interaction resulting in hallucinations and psychomotor agitationAnn Pharmacother3200842343443818303146

- HoweCRavasiaSVenlafaxine-induced deliriumCan J Psychiatry200348212912655917

- AlexanderJNillsenAVenlafaxine-induced deliriumAus NZJ Psychiatry Epub March 24, 2011

- Wyeth Australia Pty LtdEfexor®-XR [product information]Baulkham Hills, NSWWyeth Australia Pty Ltd2010

- RochatBAmeyMGilletMMeyerUABaumannPIdentification of three cytochrome P450 isozymes involved in N-demethylation of citalopram enantiomers in human liver microsomesPharmacogenetics1997711109110356

- YuBNChenGLHeNPharmacokinetics of citalopram in relation to genetic polymorphism of CYP2C19Drug Metab Dispos200331101255125912975335

- PedersenRSDamkierPBrosenKTramadol as a new probe for cytochrome P450 2D6 phenotyping: a population studyClin Pharmacol Ther200577645846715961977

- TangCShouMRushmoreTHIn-vitro metabolism of celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, by allelic variant forms of human liver microsomal cytochrome P450 2C9: correlation with CYP2C9 genotype and in-vivo pharmacokineticsPharmacogenetics200111322323511337938

- WernerUWernerDRauTFrommMFHinzBBruneKCelecoxib inhibits metabolism of cytochrome P450 2D6 substrate metoprolol in humansClin Pharmacol Ther200374213013712891223

- HalbergPKarlssonJKurlandLThe CYP2C9 genotype predicts the blood pressure response to irbesartan: results from the Swedish Irbesartan Left Ventricular Hypertrophy Investigation vs Atenolol (SILVHIA) trialJ Hypertens200220102089209312359989

- ChamSEvansMADenenbergJOGolombBAStatin-associated muscle-related adverse effects: a case series of 354 patientsPharmacotherapy201030654155320500044

- Li-Wan-PoAGirardTFarndonPCooleyCLithgowJPharmacogenetics of CYP2C19: functional and clinical implications of a new variant CYP2C19*17Br J Clin Pharmacol2010693222230 Review20233192

- HealyDLet them eat prozac: the unhealthy relationship between the pharmaceutical industry and depressionNew YorkNew York University Press2004

- HealyDThe trials. Let them eat Prozac [website on the Internet] [Nd.] Available from: http://www.healyprozac.com/Trials/default.htm. Accessed July 1, 2011

- HealyDLines of evidence on the risks of suicide with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitorsPsychother Psychosom20037227179 Review12601224

- LaughrenTPMemorandum: overview for December 13 meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC)Silver Spring, MDUS Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research2006 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/DOCKETS/ac/06/briefing/2006-4272b1-01-FDA.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2011.

- FDAAntidepressant use in children, adolescents, and adultsUS Food and Drug Administration [website on the Internet]Silver Spring, MDFDA [updated Aug 12, 2010]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/informationbydrugclass/ucm096273.htm. Accessed April 12, 2011

- HealyDHarrisRTranterRLifetime suicide rates in treated schizophrenia: 1875–1924 and 1994–1998 cohorts comparedBr J Psychiatry200618822322816507962

- LawrenceDJablenskyAVHolmanCDPinderTJMortality in Western Australian psychiatric patientsSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol200035834134711037302

- SahaSChantDMcGrathJA systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time?Arch Gen Psychiatry200764101123111317909124

- ColtonCWManderscheidRWCongruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight statesPre Chronic Dis200632A42

- BurgessPPirkisJJolleyDWhitefordHSaxenaSDo nations’ mental health policies, programs and legislation influence their suicide rates? An ecological study of 100 countriesAus N Z J Psychiatry20043811–12933939

- New South Wales (NSW) Mental Health Sentinel Events Review CommitteeTracking Tragedy: a systemic look at homicide and non-fatal serious injury by mental health patients, and suicide death of mental health inpatients. Fourth Report of the Committee New South Wales: NSW Mental Health Sentinel Events Review Committee; March 2008. [Updated and confirmed by question 10218 in NSW parliament.] Available from: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/pubs/2009/pdf/tracking_tragedy_2008_fourth_report.PDF. Accessed April 12, 2011

- American Psychiatric AssociationSchizophrenia and other psychotic disorders and Mood DisordersDiagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM IV)4th edWashington DCAmerican Psychiatric Association1994273391

- Australian Bureau of StatisticsNational Health Survey: Mental Health, Australia, 2001CanberraAustralian Bureau of Statistics [updated December 8, 2006]. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/4811.0 Accessed June 9, 2011

- OlfsonMMarcusSCNational patterns in antidepressant medication treatmentArch Gen Psychiatry200966884885619652124

- NanayakkaraPWMeijboomMSchoutenJASuicidal and aggressive thoughts as a result of taking a Hypericum preparation (St John’s wort)Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd2005611149241347134916008039

- MarksDHBregginPRBraslowDHomicidal ideation causally related to therapeutic medicationsInt J Risk Saf Med2008204231240

- MooreTJGlenmullenJFurbergCDPrescription drugs associated with reports of violence towards othersPLoS One2010512e1533721179515

- HealyDAldredGAntidepressant drug use and the risk of suicideInt Rev Psychiatry200517316317216194787

- Cem AtbaşogluESchultzSKAndreasenNCThe relationship of akathisia with suicidality and depersonalization among patients with schizophreniaJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci200113333634111514639

- ShearMKFrancesAWeidenPSuicide associated with akathisia and depot fluphenazine treatmentJ Clin Psychopharmacol1983342352366886035

- SchulteJLHomicide and suicide associated with akathisia and haloperidolAm J Forensic Psychiatry19856237

- HealyDHerxheimerAMenkesDBAntidepressants and violence: problems at the interface of medicine and lawPLoS Med200639e37216968128

- SSRI Stories: antidepressant nightmares [website on the Internet]. Available from: http://www.ssristories.com. Accessed April 12, 2011

- NewmanMBitter pills for drug companiesBMJ2010341c509520851842

- HealyDManufacturing consensusCult Med Psychiatry200630213515616804639

- Regina v Hawkins [2001] NSWSC 420, 2001

- Cassidy v Eli Lilly and Company, 2002, Civil Action No. 821, United States District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania. Available from: http://www.prozactruth.com/genetictesting.htm. Accessed April 29, 2011

- HealyDLet them eat Prozac [homepage on the Internet]. [Nd.] Available from: http://www.healyprozac.com. Accessed July 1, 2011

- Innocence Project [homepage on the Internet]New York, NY nd. http://www.innocenceproject.org. Accessed June 13, 2011