Abstract

Pharmacogenetic testing refers to a type of genetic test to predict a patient’s likelihood to experience an adverse event or not respond to a given drug. Despite revision to several labels of commonly prescribed drugs regarding the impact of genetic variation, the use of this testing has been limited in many settings due to a number of factors. In the primary care setting, the limited office time as well as the limited knowledge and experience of primary care practitioners have likely attributed to the slow uptake of pharmacogenetic testing. This paper provides talking points for primary care physicians to discuss with patients when pharmacogenetic testing is warranted. As patients and physicians become more familiar and accepting of pharmacogenetic testing, it is anticipated that discussion time will be comparable to that of other clinical tests.

Introduction

Pharmacogenetic (PGx) testing is a type of genetic test that assesses a patient’s risk of an adverse response or likelihood to respond to a given drug, informing drug selection and dosing.Citation1 As a pillar of the personalized medicine movement, PGx testing is anticipated to be important across all medical specialties,Citation2 but particularly in primary care, where the majority of all drug prescriptions are written.Citation3 It has been estimated that many of the drugs commonly prescribed by primary care practitioners (PCPs) such as fluoxetine, metoprolol, warfarin, and simvastatin are affected by PGx variation.Citation4,Citation5 Although several different strategies of delivering PGx testing have been proposed or are being investigated,Citation6–Citation8 at present, there is little clarity on which health professionals should order PGx testing, at what stage during treatment testing should be ordered, how best to communicate results to patients, and where results should be stored to inform future therapeutic decision making.Citation9 Patients prefer receiving PGx test results from a familiar provider whom they trust such as a PCP;Citation9,Citation10 however, several factors have contributed to the slow integration of PGx testing in the primary care setting,Citation11,Citation12 including limited time as well as familiarity and experience with PGx testing.Citation13–Citation15 Because PGx testing is a relatively new field and many PCPs are unfamiliar with many of the basic tenets of the field, ongoing learning opportunities and/or faculty development would enable PCPs to feel more comfortable with the topic, and presumably engage in more effective communication with patients, and more appropriate use of testing. This paper suggests key elements to be discussed with patients prior to testing and when reporting test results to assist PCPs while recognizing some of the practical limitations in the primary care setting.

Pre-test communication

Education is a hallmark of the patient–provider relationshipCitation16 and new technologies will likely warrant additional patient education until familiarity increases. PGx testing is often ideally considered as a preventative clinical test with limited risks,Citation17,Citation18 and therefore the amount of information discussed prior to testing is believed to be much less than required for a disease-based genetic test.Citation9,Citation19 However, the novelty of PGx testing and the fact that it is a DNA-based test necessitate some discussion to facilitate informed decision making. In general, written informed consent is not typically recommended or obtained,Citation20–Citation24 although some testing laboratories may require it as they do for other types of genetic testing. While some tools and educational interventions have been developed to help PCPs deliver genetic testing services, none are specific to PGx testing.Citation25–Citation28

Some patients have expressed interest in receiving information about PGx testing.Citation10,Citation29 However, PGx is a relatively new field that many providers have little experience with.Citation14,Citation15 Therefore, four main elements of PGx testing to be discussed prior to testing are suggested: (1) the purpose of testing and role of genes in drug response; (2) test risks and benefits, limitations, and alternatives; (3) emphasis that testing involves analysis of DNA; and (4) future benefits of PGx testing. As with any other clinical test, health literacy (including numeracy) may affect patients’ understanding of the purpose, risks, and benefits of PGx testing and/or the actual results.Citation30 Some of this information can be provided through patient educational materials and subsequent questions or areas of uncertainty may be discussed at a follow-up visit (). Therefore, prepared text and information relevant to the discussion of PGx testing should be readily available so that PCPs can quickly share pertinent information.

Table 1 A sample of online resources for patients and health professionals

Review purpose of test for the given prescription

The purpose of PGx testing is to determine the risk of side effects and/or likelihood of effectiveness of a given medication.Citation1 Physicians are often asked about side effects of prescribed drugs and factors that may alter the effectiveness of a drug, and if PGx testing is an option, it should be part of that conversation. In particular, PCPs can point out that a small change in a gene important in metabolizing or transporting (or other function) occurs in a subset of patients and a test is available to detect this change. The physician should briefly describe the possible outcomes regarding adjusting dose or drug selection based on the test result. Details such as gene name, specific variation, or gene function would be unnecessary.

Discuss risks/benefits, limitations, and alternative options

It should be emphasized that identification of a genetic change or metabolic activity does not necessarily indicate an absolute diagnosis of non-response or that a side effect will or will not occur upon use of a given drug. The scientific basis of the role of genes in drug response is incomplete and rapidly changing and other factors may affect drug response. In addition, although the physical risks are no greater than for any other clinical test, it should be mentioned that federal lawCitation31 prohibits any use of genetic information by health insurers and employers, though other groups may still use this information (eg, life insurers and the military). Another issue PCPs may face is patient confusion as a “normal” PGx test result doesn’t necessarily mean the patient is not at risk for adverse events or non-response because current tests only capture known variants in known genes. Additionally, other factors such as cost of testing, insurance coverage, and risk of delay of treatment while waiting for testing to be completed may influence the patient’s decision to have testing. If the patient declines to have testing, the PCP should discuss alternative interventions to limit risk of side effects or non-response as medically warranted. For example, initial dose selection can be minimized, dose escalations can be modest, a review of concomitant drugs for potential drug–drug interactions can be conducted, and selection of alternate drugs in the same class that are less susceptible to PGx interactions may be considered.

Emphasize the genetic basis of PGx testing

It is prudent to disclose that this is a DNA-based test and that specific gene(s) associated with drug response will be analyzed, particularly if one prefers to describe the test as a “drug response test” instead of using the unfamiliar and imposing term of “PGx” testing. PGx tests are considered more comparable to non-genetic clinical tests given its specific purposes and low psychosocial risk,Citation17,Citation18 but given some of the public fears associated with genetic testing,Citation32,Citation33 it should also be emphasized that the DNA sample will only be analyzed for the specific genes (unless a broader type of test is ordered) and that it will be destroyed after testing as per the laboratory’s policies. The effect of a PGx variant would only affect family members if they are exposed to the same drugs, a strong possibility if the disease is due to shared environmental and/or genetic factors. Therefore, potential familial implications of a PGx test result should be mentioned.

Discuss future benefits of testing

Given that many commonly prescribed drugs are impacted by a handful of genes such as drug transporters or drug metabolizing enzymes, it is highly likely that the result of one PGx test will be useful for future treatments. Thus, the PGx test results are not only important for the drug which prompted the testing, but potentially for other drugs prescribed in the future. Therefore, it should be emphasized that a test result can help inform other treatment decisions in the future and should be shared with other providers or perhaps the patient’s pharmacist. This will help reduce redundant testing and encourage consideration of the existing test results by other prescribing providers. Conceivably, with electronic health records, the sharing of this information might not even necessarily require direct patient or physician involvement. Furthermore, with increased use of PGx testing over time and greater accessibility of results through electronic health records, the ease of sharing genetic information amongst family members may increase, particularly if they are exposed to the same drugs.

Post-testing: communicating test results

Due to the relatively short period of time that PGx tests have been used, there are little data regarding how patients process and respond to PGx test results. Although patients have struggled with comprehending information about genetic diseases and risk,Citation34,Citation35 PGx testing is not typically presented as risks but rather as the presence or absence of a genetic variation that has been associated with a given drug response, unlike other genomic disease risk assessments.Citation36,Citation37 While the lack of certainty regarding the likelihood to develop an adverse response or not to respond to a drug at all may result in some stress, the presentation of the test result as the presence or absence of a genetic variant or as a phenotype (eg, normal metabolism) may result in better understanding. Therefore, five strategies to improve patient comprehension of PGx test results and its significance to their treatment are suggested: (1) use effective risk communication strategies; (2) inform patients what, if any, changes will be made to the prescribed drug; (3) re-emphasize relevance of test results for future treatments; (4) make referrals as necessary; and (5) provide a patient letter. Additionally, provides suggested text for discussion using the example of PGx testing for simvastatin to illustrate how these key elements may be communicated to patients.

Table 2 Sample text based on the proposed strategy for post-testing communication using the example of SLCO1B1 for simvastatin (statin-induced myalgia has been associated with a variant in the hepatic transporter gene, SLCO1B1, particularly in patients prescribed simvastatin and to a lesser degree, atorvastatin)Citation55,Citation56

Use effective risk communication strategies

As with any clinical test, the communication of test results should be tailored to the patient’s needs and concerns since not all risk information may be informative or useful to patients.Citation38 For PGx testing, it is probably less important for patients to understand their specific genotype, and more important to present the significance of the results (ie, slower than normal ability to break down this drug). Risk communication for PGx results should focus on the likelihood of a particular drug causing side effects and whether or not the drug will be effective. When communicating risk, it is important to be cognizant of potential negative connotations associated with certain commonly used phenotypic descriptors (eg, “poor” metabolizer). As with other medical information, use of medical jargon should be limited or defined if used.

Inform patients what, if any, changes will be made to the prescribed drug

If adjustments to drug selection or dosing are warranted based on the patient’s PGx test result, discuss what changes will be made and the purpose of the change.

Re-emphasize relevance of test results for future treatments

PCPs should remind patients of the potential significance of the current PGx test result for future treatments and encourage sharing of the test result with other providers. Studies have reported that some individuals that had PGx testing recognized the implications of testing for future drugsCitation39 and asked about the future use of other drugs after receiving results.Citation17 Ideally, PGx test results should automatically be included in the medical record just as a standard complete blood count or pathology result is appended to the record. Inaccessible PGx results could lead to much confusion, frustration, and potentially poorer patient and family outcomes. Patients can share the patient summary letter or a copy of the test report, or some type of summary record of their results kept on a card or something akin to an immunization record, particularly if they have had PGx testing for different genes. Patients have indicated their willingness to keep their results on a card or other convenient device.Citation40

Make referrals as necessary

Some PGx variants not only affect drug responses but also disease risk.Citation41–Citation43 For example, a variant in the apolipoprotein E (ApoE) gene has been linked to low-density lipoprotein response to statins,Citation44 with an ancillary effect on Alzheimer’s disease risk.Citation44,Citation45 Some studies have suggested that providers should disclose the existence of ancillary risk information to enable patients to decide if they would want to learn of these results.Citation46,Citation47 If a PGx variant has an ancillary effect, the benefits of knowing the PGx variant to inform treatment should outweigh the risks of revealing a potential disease risk variant. In the case of ApoE, the effect on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol lowering appears minimal, and therefore the benefit of the PGx knowledge would not be greater than the risks and additional efforts associated with genetic counseling and testing for Alzheimer’s disease. Another approach, though controversial, is to not report individual genotype in the test results and instead simply report the expected phenotype, eg, poor response to statin, increased dose recommended. Because genetics professionals are likely better trained to discuss disease risk information, it may be prudent for PCPs to refer their patient to a genetics professional if a test with ancillary disease information is ordered. Additionally, genetic counseling may be beneficial for patients that exhibit difficulty in understanding or coping with the results.Citation39 Therefore, to assist PCPs, it would be helpful to have a simple process established for genetics referrals when complex situations or results come back. Such a process may enhance both patient and provider acceptance of PGx and other types of genetic testing.

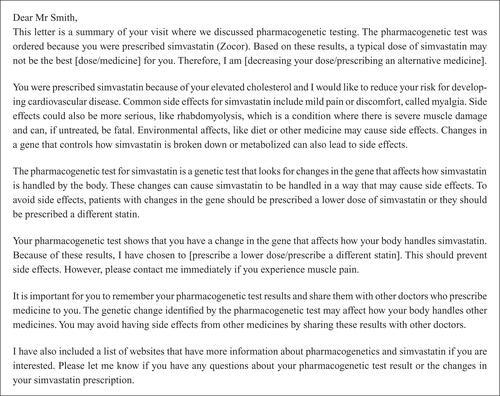

Provide a patient letter

It is common practice for genetic counselors to send a follow-up summary letter, reviewing the reason for testing, the name/type of test ordered, the results of the test, the implications of those results, and recommendations for follow-up. The letter may also include educational resources such as websites for patients to seek additional information if desired. Providing after-visit summaries is becoming more prevalent and useful in this increasing age of electronic health records for other medical specialties. Since it is not uncommon to deliver test results over the phone or via letter when follow-up visits cannot be scheduled in a timely manner or deemed unnecessary (eg, results are normal), some prepared text about PGx testing may help patients fully comprehend their results and PCPs quickly return patient test results (see Supplemental Figure). Particularly important for PGx testing, the letter may be shared with other providers providing treatment.Citation48–Citation51 Patient satisfaction and understanding of results received through other forms of communication have been shown to be comparable to those that receive results in-person.Citation52–Citation54

Conclusion

Given the limited time with patients in a primary care setting, the amount of information that can be conveyed to patients about PGx testing will be quite limited. The talking points provided in this paper should provide some guidance on the core elements needed to reach an informed decision about PGx testing. In combination with other resources, PCPs can adequately and effectively discuss PGx testing with their patients. As patient familiarity increases and PGx testing becomes standard of care, the amount of discussion will likely be substantially less, primarily limited to the results and its impact on drug selection and dosing.

Supplementary Figure

An example of a patient letter for PGx testing following recommended content. Patient letters are routinely sent by genetic counselors to provide patients with an overview of the patient visit(s) and are separate from chart notes or letters to other physicians. Its primary purpose is to serve as a record of medical information and promote patient understanding.

Figure S1 Patient letter for PGx simvastatin testing.

Note: Data from.Citation1

Reference

- PharmGKB: Simvastatin [homepage on the Internet]Stanford, CAThe Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebasec2001–2013 [updated July 1, 2013]. Available from: http://pharmgkb.org/drug/PA451363Accessed July 24, 2013

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WangLMcLeodHLWeinshilboumRMGenomics and drug responseN Engl J Med2011364121144115321428770

- ManolioTAChisholmRLOzenbergerBImplementing genomic medicine in the clinic: the future is hereGenet Med201315425826723306799

- CDC/NCHSNational Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 Summary TablesAtlanta, GACenters for Disease Control and Prevention2010 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2010_namcs_web_tables.pdfAccessed August 1, 2013

- FruehFWAmurSMummaneniPPharmacogenomic biomarker information in drug labels approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration: prevalence of related drug usePharmacotherapy200828899299818657016

- GriceGRSeatonTLWoodlandAMMcLeodHLDefining the opportunity for pharmacogenetic intervention in primary carePharmacogenomics200671616516354125

- CrewsKRHicksJKPuiCHRellingMVEvansWEPharmacogenomics and individualized medicine: translating science into practiceClin Pharmacol Ther201292446747522948889

- PulleyJMDennyJCPetersonJFOperational implementation of prospective genotyping for personalized medicine: the design of the Vanderbilt PREDICT projectClin Pharmacol Ther2012921879522588608

- MillsRHagaSBClinical delivery of pharmacogenetic testing services: a proposed partnership between genetic counselors and pharmacistsPharmacogenomics201314895796823746189

- FargherEAEddyCNewmanWPatients’ and healthcare professionals’ views on pharmacogenetic testing and its future delivery in the NHSPharmacogenomics20078111511151918034616

- PayneKFargherEARobertsSAValuing pharmacogenetic testing services: a comparison of patients’ and health care professionals’ preferencesValue Health201114112113421211494

- SwenJJGuchelaarHJJust how feasible is pharmacogenetic testing in the primary healthcare setting?Pharmacogenomics201213550750922462740

- van SchieRMde BoerAMaitland-van der ZeeAHImplementation of pharmacogenetics in clinical practice is challengingPharmacogenomics20111291231123321919599

- ShieldsAELermanCAnticipating clinical integration of pharmacogenetic treatment strategies for addiction: are primary care physicians ready?Clin Pharmacol Ther200883463563918323859

- HagaSBBurkeWGinsburgGSMillsRAgansRPrimary care physicians’ knowledge of and experience with pharmacogenetic testingClin Genet201282438839422698141

- StanekEJSandersCLTaberKAAdoption of pharmacogenomic testing by US physicians: results of a nationwide surveyClin Pharmacol Ther201291345045822278335

- BirdJCohen-ColeSAThe three-function model of the medical interview. An educational deviceAdv Psychosom Med19902065882239506

- MadadiPJolyYAvardDThe communication of pharmacogenetic research results: participants weigh in on their informational needs in a pilot studyJ Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol201118e152e15521467605

- RosesADPharmacogenetics and the practice of medicineNature2000405678885786510866212

- CallardANewmanWPayneKDelivering a pharmacogenetic service: is there a role for genetic counselors?J Genet Couns201221452753522052043

- RobertsonJAConsent and privacy in pharmacogenetic testingNat Genet200128320720911431685

- RobertsonJABrodyBBuchananAKahnJMcPhersonEPharmacogenetic challenges for the health care systemHealth Aff (Millwood)200221415516712117126

- WoelderinkAIbarretaDHopkinsMMRodriguez-CerezoEThe current clinical practice of pharmacogenetic testing in Europe: TPMT and HER2 as case studiesPharmacogenomics J2006613716314885

- HedgecoeA“At the point at which you can do something about it, then it becomes more relevant”: informed consent in the pharmacogenetic clinicSoc Sci Med20056161201121015970231

- HedgecoeAMContext, ethics and pharmacogeneticsStud Hist Philos Biol Biomed Sci200637356658216980195

- CarrollJCRideoutALWilsonBJGenetic education for primary care providers: improving attitudes, knowledge, and confidenceCan Fam Physician20095512e92e9920008584

- CarrollJCWilsonBJAllansonJGenetiKit: a randomized controlled trial to enhance delivery of genetics services by family physiciansFam Pract201128661562321746696

- EmeryJWaltonRMurphyMComputer support for interpreting family histories of breast and ovarian cancer in primary care: comparative study with simulated casesBMJ20003217252283210875832

- WatsonEClementsAYudkinPEvaluation of the impact of two educational interventions on GP management of familial breast/ovarian cancer cases: a cluster randomised controlled trialBr J Gen Pract20015147181782111677705

- HaddyCAWardHMAngleyMTMcKinnonRAConsumers’ views of pharmacogenetics: a qualitative studyRes Social Adm Pharm20106322123120813335

- LeaDHKaphingstKABowenDLipkusIHadleyDWCommunicating genetic and genomic information: health literacy and numeracy considerationsPublic Health Genomics2011144–527928920407217

- The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 [webpage on the Internet]Washington, DCUS Equal Employment Opportunity Commission2008 Available from: http://www.eeoc.gov/laws/statutes/gina.cfmAccessed May 21, 2013

- HallMAMcEwenJEBartonJCConcerns in a primary care population about genetic discrimination by insurersGenet Med20057531131615915082

- KlitzmanRViews of discrimination among individuals confronting genetic diseaseJ Genet Couns2010191688320054623

- KaphingstKAMcBrideCMWadeCPatients’ understanding of and responses to multiplex genetic susceptibility test resultsGenet Med201214768168722481132

- KlitzmanRLMisunderstandings concerning genetics among patients confronting genetic diseaseJ Genet Couns201019543044620512408

- BlossCSWineingerNEDarstBFSchorkNJTopolEJImpact of direct-to-consumer genomic testing at long term follow-upJ Med Genet201350639340023559530

- 23andme.com [homepage on the Internet]Genetic testing for health, disease, and ancestry2007 [updated August 1, 2013]. Available from: http://23andme.comAccessed July 17, 2013

- Zikmund-FisherBJThe right tool is what they need, not what we have: a taxonomy of appropriate levels of precision in patient risk communicationMed Care Res Rev201370Suppl 137S49S22955699

- MadadiPJolyYAvardDCommunicating pharmacogenetic research results to breastfeeding mothers taking codeine: a pilot study of perceptions and benefitsClin Pharmacol Ther201088679279520739920

- HagaSBKawamotoKAgansRGinsburgGSConsideration of patient preferences and challenges in storage and access of pharmacogenetic test resultsGenet Med2011131088789021673581

- HagaSBBurkeWPharmacogenetic testing: not as simple as it seemsGenet Med200810639139518496219

- HenriksonNBBurkeWVeenstraDLAncillary risk information and pharmacogenetic tests: social and policy implicationsPharmacogenomics J200882858917486108

- NetzerCBiller-AndornoNPharmacogenetic testing, informed consent and the problem of secondary informationBioethics200418434436015449406

- VooraDGinsburgGSClinical application of cardiovascular pharmacogeneticsJ Am Coll Cardiol201260192022742397

- TanziREThe genetics of Alzheimer diseaseCold Spring Harb Perspect Med2012210pii 006296

- HagaSBO’DanielJMTindallGMLipkusIRAgansRSurvey of US public attitudes toward pharmacogenetic testingPharmacogenomics J201212319720421321582

- HagaSBO’DanielJMTindallGMLipkusIRAgansRPublic attitudes toward ancillary information revealed by pharmacogenetic testing under limited information conditionsGenet Med201113872372821633294

- CassiniCThauvin-RobinetCVinaultSWritten information to patients in clinical genetics: what’s the impact?Eur J Med Genet201154327728021420514

- EssexCConsultants could give patients a letter summarising their consultationBMJ199831671327069522815

- RaoMFogartyPWhat did the doctor say?J Obstet Gynaecol200727547948017701794

- HallowellNProviding letters to patients. Patients find summary letters usefulBMJ1998316714718309624093

- BaumanisLEvansJPCallananNSussweinLRTelephoned BRCA1/2 genetic test results: prevalence, practice, and patient satisfactionJ Genet Couns200918544746319462222

- SanghaKKDircksALangloisSAssessment of the effectiveness of genetic counselling by telephone compared to a clinic visitJ Genet Couns2003122171184

- HarrisonHFHarrisonBWWalkerAPScreening for hemochromatosis and iron overload: satisfaction with results notification and understanding of mailed results in unaffected participants of the HEIRS studyGenet Test200812449150018939938

- LinkEParishSArmitageJSEARCH Collaborative GroupSLCO1B1 variants and statin-induced myopathy: a genomewide studyN Engl J Med2008359878979918650507

- VooraDShahSHSpasojevicIThe SLCO1B1*5 genetic variant is associated with statin-induced side effectsJ Am Coll Cardiol200954171609161619833260

- PharmGKB: Simvastatin [homepage on the Internet]Stanford, CAThe Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebasec2001–2013 [updated July 1, 2013]. Available from: http://pharmgkb.org/drug/PA451363Accessed July 24, 2013