Abstract

Sleep is a critical component of healthy development for youth, with cascading effects on youth’s biological growth, psychological well-being, and overall functioning. Increased sleep difficulties are one of many disruptions that adopted youth may face throughout the adoption process. Sleep difficulties have been frequently cited as a major concern by adoptive parents and hypothesized in the literature as a problem that may affect multiple areas of development and functioning in adopted youth. However, there is limited research exploring this relationship. Using a biopsychosocial framework, this paper reviews the extant literature to explore the development, maintenance, and impact of sleep difficulties in adopted youth. Finally, implications for future research and clinical interventions are outlined.

Introduction

During childhood and adolescence, quality sleep is critical for the development of good physical and mental health, particularly for vulnerable populations.Citation1,Citation2 Sleep is regulated through two biological processes, the circadian rhythm and homeostatic system, both of which are influenced by environmental factors.Citation3 Psychosocial stressors may disturb sleep and the biological regulation processes which, in turn, may disrupt daily functioning, impair physical and mental health, and negatively influence development.Citation1,Citation4,Citation5 This cycle of disruption may result in long-term changes in the biological processes that regulate sleep as well as chronic sleep difficulties and physical and mental health consequences.Citation6,Citation7 Further, research indicates that sleep difficulties often persist into adulthood, and are accompanied by cascading negative outcomes.Citation8 Improving sleep in youth has been targeted as a critical area for intervention due to the potential for a wide range of positive outcomes.Citation9,Citation10

In 2012, nearly 400,000 children were in the foster system in the US, of which greater than 50,000 were adopted while another 100,000 waited to be adopted.Citation11 Including international adoptions in 2008, more than 130,000 children were adopted into homes in the US.Citation12 Further, the pre-adoption experiences and adoption pathways are heterogeneous, influencing their development in a number of ways.Citation13 Overall, adopted youth are at increased risk for developing sleep difficulties and associated negative biopsychosocial outcomes.Citation14,Citation15 The process from pre-adoption through post-adoption is replete with biopsychosocial risk factors for sleep difficulties including stress, abuse, neglect, psychopathology, other environmental or parental dysfunction, inconsistency, or disruption.Citation16,Citation17 These factors can influence neurobiological functioning and increase adopted youth’s risk for sleep difficulties, which may further complicate the many challenges adopted youth already experience throughout the adoption process.Citation16,Citation18 Further, adoptive parents cite sleep difficulties as a primary concern and as an opportunity for targeted treatment.Citation19,Citation20 However, despite the wealth of research on environmental risk factors in adopted youth, there is limited research on how these factors influence sleep in adopted youth. Finally, post-adoption, there are often protective factors that begin to stabilize risk factors, improving sleep and psychosocial outcomes for adopted youth.Citation21

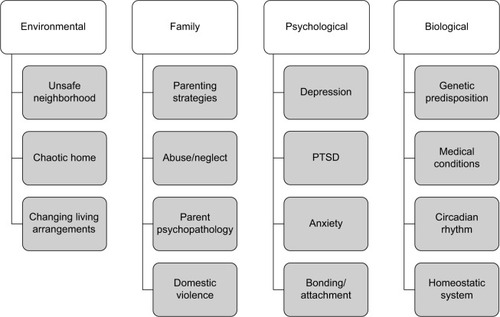

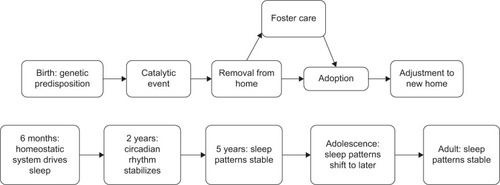

The present paper reviews the literature on sleep in adopted youth, focusing particularly on adoption-related psychosocial stressors that may exacerbate and maintain sleep difficulties. First, common familial psychosocial stressors (ie, family, mental health, physical environment) experienced by adopted youth are outlined. Of note, psychosocial stressors that extend beyond the home environment (eg, peer, school, cultural), as well as genetic components, are outside the scope of this review. Further, the existing literature primarily focuses on American families adopting internationally, which excludes children who have been through domestic foster care in the US. Because of the limited literature on sleep in domestic adoptees, papers on international adoption are included with the goal of identifying pre- and post-adoption risk factors that may be generalizable to domestic studies. Subsequently, emphasis is placed on how these psychosocial stressors influence key biological systems that contribute to sleep difficulties, as well as how these sleep difficulties may contribute to detriments in mental health. provides an overview of the factors being considered and shows the common trajectories for children who are adopted superimposed on a timeline illustrating the key normal developmental changes in sleep which take place. Finally, future directions and implications are explored.

Limited literature on sleep in adoption

Currently, there is limited research available that specifically examines sleep in adopted youth. Literature searches were conducted using PubMed and PsycINFO which included combinations of the following key terms: sleep, sleep difficulties, sleep disturbances, and insomnia; adoption, adopted, foster, and foster care; and child, children, youth, adolescents, and teens. Studies were included for review if they examined any aspect of routine or abnormal sleep in youth who had been adopted. Youth were defined as children between birth and 17 years old. The resulting seven studies are described in .

Table 1 Studies found that examine sleep in adopted youth

All seven studies show that sleep difficulties are common in adopted youth.Citation15,Citation20,Citation22–Citation26 Maltreatment and institutionalization prior to adoption predicted poorer sleep post-adoption.Citation22,Citation23,Citation26 In the only study of post-adoption risk factors, marital discord at baseline was found to predict sleep problems at follow-up.Citation24 These findings highlight that both pre- and post-adoption factors play important roles in youth sleep. Further, to manage post-adoption sleep difficulties, parents reported high levels of co-sleeping with distressed infants and an increased need to provide physical and verbal soothing.Citation15,Citation20 In the only study to examine school-aged children, maltreatment prior to adoption related to sleep difficulties, and independently, sleep difficulties were related to disruptive behavior.Citation22 Finally, a study on institutionalized adopted Chinese girls demonstrated that adverse environments may have a biological impact on sleep issues, as children experienced higher asymmetry tympanic membrane temperatures (an indicator of physical well-being, cerebral temperature, and hemispheric lateralization) coupled with sleep difficulties prior to adoption.Citation23 However, these results were not maintained at 9-month follow-up, possibly indicating that biological aspects of sleep difficulties reduce as sleep difficulties decrease post-adoption. Taken collectively, these findings suggest that it is not just pre-adoptive experiences that influence psychosocial outcomes post-adoption.

The current body of literature has several notable limitations. First, most studies examine internationally adopted Asian female infants,Citation15,Citation20,Citation23,Citation25,Citation26 and only two studies have used a short-term longitudinal design.Citation23,Citation24 This is important because domestic adoptions and older children make up a significant number of adoptions,Citation11,Citation12 which limits our ability to understand the influence of pre-adoption events and adoption on sleep during later childhood and adolescence. Further, only two studies measured sleep with validated sleep questionnaires,Citation22,Citation24 while the remaining used select questions off of behavior measures or developed their own.Citation15,Citation20,Citation23,Citation25,Citation26 The use of these instruments often results in less descriptive data on the nature of these sleep difficulties and reduces generalizability or replication. Most of these studies are based on qualitative research.Citation15,Citation20,Citation23,Citation26 As a result, it has been difficult to formulate or test an inclusive biopsychosocial model that can explain the findings in these studies. Given the paucity of literature specifically on foster/adopted children and sleep, the following sections review related sleep literature (eg, trauma, chaotic environments) in order to frame the discussion of the adoption literature.

Psychosocial factors

Psychosocial risk factors during adoption process

The majority of risk factors experienced by adopted youth occur prior to adoption, during their time with their biological parents, transitioning care, or foster/temporary care. These factors place them at risk for a variety of mental and physical health outcomes, including sleep difficulties.Citation27 The reason for removal from their biological home may be a traumatic experience for each child. The most common reasons for removal include child abuse, child neglect, parental substance use, parental incarceration, parental death, or child behavioral problems.Citation28,Citation29 Further, children who are abused or neglected are more likely to live in a community with increased violence levels, which can compound trauma exposure. Even when children are removed from harmful home environments for their safety and well-being, losing their parents can be in and of itself a traumatic experience.Citation28

As a result of these stressors, greater than 30% of children entering the foster system have serious mental health issues (eg, depression, anxiety, or disruptive behavior disorders) or developmental problems (eg, delayed/stunted growth or speech and language difficulties).Citation28 Notably, the median age at entry to foster care is 6.4 years old, with the mean age of children in foster care being 8.9 years old.Citation11 Children who are placed in the foster system stay in the system for an average of 33 months and typically experience one or more changes in caregivers.Citation11,Citation28 This is a period in development where sleep patterns normally become stabilized, though this is likely to be contingent on establishment of a consistent sleep routine and stable sleep environment.

In the past, the predominant wisdom was that it was best to remove children from harmful living situations; however, recent research is showing that removal is a far more complex issue.Citation30 Compared to children who remain in their biological home (even in the case of similar risk factors with maltreatment), children who have experienced foster care were more likely to have serious behavior and internalizing problems.Citation30 This may be the result of children placed in foster care undergoing a traumatic (though temporary) loss of their parents coupled with adapting to a new home environment and forging attachments with new caregivers. It may also be attributable to the success of family-based interventions that were administered to families flagged for maltreating their children but whose children stayed in the home.Citation30 This issue is further complicated for older children, and children who have behavioral problems are more likely to experience multiple foster homes and remain in the foster system longer.Citation29 As a result, during this important developmental window, these children are forging new attachments and rebuilding their social support on top of navigating typical developmental milestones. These disruptions may increase child stress, directly influencing sleep and its neurobiological regulation system.Citation14,Citation31 Despite the potential for negative outcomes associated with foster care, many children who are adopted experience improvements across physical and mental health domains,Citation13,Citation17,Citation21,Citation32,Citation33 and adoption is viewed as significantly more favorable than remaining in foster care.

Psychosocial influences of sleep

Youth experience a wide variety of psychosocial stressors that may influence their ability to obtain quality sleep. This section focuses on psychosocial risk factors influencing sleep which are related to family, mental health, and physical environment. Risk factors associated with these areas have been linked to negative sleep outcomes and may be present in the pre- and post-adoption lives of adopted youth.Citation1,Citation34 These factors may result in the biological disruptions of sleep regulation, which in turn may maintain sleep difficulties ( and ).Citation4,Citation35

Family factors

Family-related stressors can greatly influence a child’s ability to achieve quality sleep. Violence in the home, parent substance abuse, parent mental health, parenting style and super-vision, family structure, and family beliefs about sleep all contribute to the development of sleep patterns in youth.Citation36,Citation37

Children may be exposed to a variety of behaviors by their parents, including domestic violence, substance abuse, and a parent’s own mental health struggles.Citation37 A recent study in the Netherlands found that children exposed to intimate partner violence were more likely to have difficulty sleeping, slept less, had more nightmares, and more frequent nocturnal enuresis, some of which may persist into adulthood.Citation8,Citation38 Further, electroencephalograms of sleeping children whose parents have a history of substance abuse showed decreased activity in thalamus regions that protect sleep, making them more vulnerable to sleep difficulties.Citation39 Finally, higher levels of parental depression and other psychopathology are related to children having difficulty initiating sleep, particularly when mothers are emotionally unavailable.Citation40,Citation41 Thus due to parental psychopathology, children may not have structured bedtime, may not have their emotional needs met, or may experience detrimental parenting behaviors, in turn influencing their ability to get enough quality sleep.

Additionally, children who are abused, neglected, or experience family conflict are more likely to experience sleep difficulties.Citation42 There is evidence that youth who are abused/neglected experience sleep difficulties during childhood, adolescence, and into adulthood, demonstrating both the immediate and lasting effects of abuse/neglect on youth sleep.Citation37,Citation42 Youth who were placed in state custody due to parental neglect or physical abuse from parents have higher rates of sleep difficulties and decreased sleep efficiency than youth in state custody who had not experienced abuse or neglect.Citation43,Citation44 Further, family conflict during childhood and early adolescence predict sleep difficulties during late adolescence.Citation37

In addition to conflict, parent–child attachment and parenting style may both play an important role in children’s sleep. Toddlers who are more securely attached to their primary caregiver(s) are more likely to have higher sleep quality and quantity,Citation45 while infants and toddlers who have a disorganized or insecure attachment sleep less, have poorer sleep quality, and have more awakenings.Citation46 Vaughn et alCitation47 found that these trends remain stable as children grow older. In addition to attachment, parenting styles play a role in bedtime structure, which is linked to a child’s ability to fall and stay asleep.Citation48 Higher levels of parent warmth relate to increased quantity of sleep in youth under age 11, while adolescents obtain more sleep when their parents practice higher parental monitoring and control.Citation49 These studies show the importance of parent–child interaction and bonding as a means to establish an effective bedtime routine and ensure that the child feels safe and relaxed in bed.

Mental health

Mental health concerns have been discussed extensively in relation to sleep difficultiesCitation50–Citation52 and also adopted youth.Citation53–Citation55 In this section, mental health concerns that are most prominent in adopted youth are focused on particularly as they pertain to initiation and maintenance of sleep difficulties. Adopted youth access mental health services at higher rates and are more likely to have more severe presentations.Citation54,Citation55 They are more likely to have experienced abuse or neglect and engage in disruptive behaviors.Citation54 They present with internalizing disorder rates comparable to their non-adoptive peers.Citation53,Citation54 While this relation is well established, it remains difficult to determine the causal direction, and likely, it is bidirectional in nature.Citation50,Citation56 The relationship between mental health and sleep issues is so intertwined that sleep difficulties can be viewed as a risk factor for mental health concerns and a symptom of others. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (fifth edition),Citation57 a number of anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and trauma-related disorders have some form of sleep dysregulation as a symptom.

Both internalizing and externalizing disorders have been implicated in the disruption of sleep.Citation51,Citation56 Armstrong et alCitation51 followed a cohort of children throughout childhood and adolescence, and found that at age 4, hostile/aggressive and hyperactive behaviors were associated with sleep difficulties. At age nine, children with sleep difficulties were more likely to have depressive symptoms, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or externalizing behaviors. For adolescents at age 18, anxiety and externalizing behaviors were associated with difficulty sleeping. Further, in a review of sleep difficulties in mood disorders, Lofthouse et alCitation56 found that from early childhood to late adolescence, mood disorders were associated with an increase in sleep difficulties. Similar research has found that anxiety during childhood and adolescence is associated with an increase of sleep difficulties including quality and quantity of sleep.Citation58 As noted, children who have experienced or witnessed traumatic events are more likely to have difficulty sleeping.Citation42

There are a number of proposed mechanisms behind the relationship between youth psychopathology and sleep difficulties. Youth who experience affective disturbances (ie, difficulty regulating emotions, negative self-perceptions, and dysphoric mood) are more likely to have both sleep difficulties and psychopathology such as depression and anxiety.Citation42 These disturbances may increase arousal in youth impairing their ability to get the required quantity and quality of sleep. As a part of increased arousal, engaging in cognitive rumination about past events, worries, or depressive thoughts may further decrease the ability to fall asleep.Citation59 Further, youth with anxiety and heightened fear expression may not view their home or bedroom as safe place and thus have a harder time relaxing and feeling comfortable while they sleep.Citation52 These fears may be greater in youth who have experienced abuse or trauma in their bedroom or at home, particularly at night. Lower cognitive flexibility may also play a role in these fears as these youth cannot engage in effective coping strategies.Citation42 As a result of this complex relation, it is easy to see how mental health concerns may be both a catalytic and a maintaining factor for sleep difficulties for some children.

Physical environment

Children’s physical environment influences their ability to obtain sufficient and good-quality sleep. Adopted youth typically see an improvement in their physical environmentCitation34 but may experience any number of stressors that could impair sleep.Citation60–Citation63 For example, preadolescent youth who are exposed to unsafe or hostile home environments are more likely to experience difficulty sleeping.Citation60 More broadly, living in a community with elevated crime rates is associated with increased sleep difficulties in adolescents.Citation61 Further, if impoverished adolescents witness violent crimes, they are also more likely to have insomnia, nightmares, and daytime sleepiness in addition to greater autonomic nervous system (ANS) activation and reactivity.Citation62,Citation63

In addition to needing a safe overall environment, children benefit from a comfortable bedroom environment that is conducive to sleep. Sleep duration was even shorter among minority and older youthCitation64 and has been further related to disruptive night time noises.Citation50 Sharing a bed or room is also related to shorter sleep duration across youth ages and is more common in Eastern cultures, single-parent households, and low socioeconomic status homes.Citation50,Citation65,Citation66 If co-sleeping continues for more than a year, disrupted sleep behaviors may become habitual in children.Citation67

The biology of sleep and adoption

Biological regulation of sleep

Sleep regulation occurs through two biological processes: the circadian rhythm and the homeostatic system.Citation68 These two systems work together to regulate the sleep/wake cycle in the body. The circadian rhythm is the 24-hour “wake drive” which determines alertness and works like a clock. Its rhythm refreshes daily based on cues such as light exposure and temperature.Citation69 The homeostatic system, “sleep drive”, is a sleep-dependent process driven by the gradually increasing need for sleep (sleep pressure), which builds throughout the day and releases at night, like a spring.Citation69 Both processes rely on neurochemicals for regulation. The parabolic increase and decrease of melatonin drive the sleep/wake cycle of the circadian rhythm,Citation69,Citation70 while sleep pressure is regulated by adenosine increasing linearly throughout the day.Citation71

A number of neural structures have been implicated in regulation of sleep.Citation72 The circadian rhythm is driven primarily by the hypothalamus but is also regulated in part by the pituitary gland and melatonin-producing pineal gland.Citation70 The homeostatic system is regulated in part by the basal forebrain, a group of acetylcholine-producing structures in the cortex.Citation73 In this way, the homeostatic system is related to the cortico-limbic system, which includes regions of the basal forebrain and regulates cognitive arousal through acetylcholine.Citation73 Regions of the cortico-limbic system implicated in sleep include the amygdala, hippocampus, thalamus, and hypothalamus. Further, the cortico-limbic regions work with the sympathetic nervous system to help to regulate the body during sleep.Citation74 Finally, the ANS, regulated primarily by the hypothalamus, helps to maintain homeostasis in the body including sleep and the threat response.Citation75 Thus, the hypothalamus and basal forebrain participate in multiple modes of regulation; a redundancy that may make sleep disruption difficult.

At birth, these biological mechanisms do not fully regulate sleep, but as children develop, regulation of sleep begins to stabilize. Prior to 6 months, children’s circadian rhythm is not yet developed, so sleep is primarily driven by their homeostatic rhythm.Citation70 By age two, the circadian rhythm and homeostatic system are working together to facilitate nocturnal sleep, while the homeostatic rhythm will often drive napping.Citation76 Circadian and homeostatic rhythms begin to stabilize around age two, and by age five become set patterns that are difficult to change.Citation76,Citation77 From age five until adolescence, these rhythms continue to work together to regulate sleep, and gradually, the homeostatic need for naps declines. During adolescence, sleep/wake times shift later, due to the biological changes associated with puberty as well as psychosocial factors.Citation78 During their twenties, young adults fall into a stable sleep cycle, requiring 6–8 hours of sleep that relies on both circadian and homeostatic rhythms to regulate. However, at any stage during development, these sleep patterns may be derailed by a number of psychosocial factors.

Biological disruption of sleep

Neurobiological disruption has been independently associated with both sleep difficulties and the psychosocial stressors seen in adopted youth.Citation4,Citation35 These biological consequences are varied and range in severity and length of their influence. Both temporary and long-term sleep difficulties may have concurrent influences on next-day functioning, while the long-term presence of sleep difficulties may also have lasting neurobiological implications.Citation79 Psychosocial stressors, like those experienced pre-adoption, may have similar lasting effects on neurobiology.Citation80,Citation81 This section focuses on the lasting neurobiological implications which tend to relate to longer-term sleep difficulties and long-term exposure to psychosocial stressors.Citation79,Citation82

The psychosocial stressors that impact adopted youth discussed are associated with dysregulation in the regions and pathways that regulate sleep. As the cortico-limbic system is associated with affect and mood, mood disorders (ie, depression and bipolar) have been associated with dysfunction in this system – particularly the hypothalamus, amygdala, and hippocampus.Citation80,Citation81,Citation83 During adolescence, decreases in cortico-limbic gray matter are associated with childhood maltreatment.Citation84 Further, hypothalamus–pituitary dysregulation has been associated with increases in anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and physical or emotional abuse directed at the child.Citation35,Citation80,Citation85

As sleep is disrupted by these stressors, the endogenous systems and brain regions associated with sleep change.Citation86 Connectivity decreases between regions in the cortico-limbic pathway and its associated sleep regulation locations.Citation87,Citation88 Greater reactivity of the ANS, which is primarily regulated by the hypothalamus, is associated with decreased sleep quantity through increased activation of the neural pathways linked to homeostasis.Citation89 Further, hypothalamic and pituitary hyperactivity and dysfunction are associated with decreased sleep quantity in children and adolescents.Citation4,Citation86 As these changes occur, the ability to regulate sleep decreases, and sleep difficulties become stabilized neural pathways.Citation90 Further, these neurobiological changes may increase physiological arousal at bedtime.Citation91 As a result, the brain is increasing wakefulness instead of inducing relaxation and rest.

Neurobiological effects of adoption process

As noted, the brain regions responsible for sleep regulation are also responsible for a number of other functions. As such, they can be influenced by a variety of external stressors. For adopted youth, the adoption process represents an external stressor that can influence the neurobiology of these regions.Citation92,Citation93 Both the limbic system and hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis may undergo changes during the adoption process.Citation92,Citation94,Citation95 These changes may result in the dysregulation of regions also responsible for sleep regulation.

The HPA axis is the primary region indicated in neurobiological change during the adoption process. The HPA axis is responsible for the biological stress response in addition to other homeostatic and autonomic processes in the body.Citation96 As a result, increased stress from time spent in a stressful home environment, foster care, or transitioning care can lead to dysregulation of the HPA stress response and of other HPA-controlled homeostatic systems such as sleep.Citation14,Citation97 Children who experienced emotional abuse prior to adoption were more likely to experience decreased HPA axis activity, while children experiencing physical neglect had increased HPA axis activity with both resulting in pervasive HPA dysregulation.Citation97 Further, children in the foster care system exhibit continued elevated HPA activity, impairing normative HPA functioning.Citation92 Finally, adopted children with internalizing problems experience decreased HPA axis activity, while adopted children with externalizing problems experience increased HPA axis activity.Citation98 Adopted children may experience HPA axis dysregulation at all these stages, and the cumulative effects may result in stabilization of the dysfunction of the HPA axis.Citation98

To date, the disruption of the ANS processes and limbic pathways has only been studied in international youth with a history of institutionalization.Citation95,Citation99 Children who have been in an institution prior to adoption have increased sympathetic nervous system activity. The sympathetic nervous system is the activating branch of the ANS, which is responsible for the stress/threat response and overriding the parasympathetic relaxation response.Citation99 Neuroimaging indicates a significant decrease in limbic white matter volume and connectivity in adopted children who experience significant neglect or deprivation.Citation95 Both studies implicated increased stress experienced by neglected and deprived children as the likely cause for these results. Thus, it may be hypothesized that adopted youth in the US who experienced significant neglect prior to adoption may show similar ANS and limbic disruptions.

Outcomes

Psychosocial outcomes of sleep difficulties

With the disruption of biological systems, a youth’s ability to navigate psychosocial stressors is hindered, and many mental health and psychosocial outcomes have been linked to sleep difficulties.

Sleep difficulties have particularly salient effects on neurocognitive and social functioning. Children who sleep poorly may have difficulty paying attention in school, process information slower, or struggle to regulate their emotions.Citation6,Citation100 School-aged children with poor sleep were more likely to be aggressive and have social–relational difficulties, behaviors which can persist into adolescence.Citation101,Citation102 Further, sleep difficulties were associated with poor school performance and behavioral problems.Citation10,Citation102 Youth with sleep difficulties experience greater difficulty paying attention, concentrating on work, and forming and retaining memories.Citation10,Citation103 Youth of all ages who reported shortened sleep duration also reported poorer quality of life and perceived less social support than their peers.Citation10

Effects of adoption

The effects of adoption are generally viewed as positive in nature, and youth experience many gains as their lives begin to stabilize in their new family.Citation21 Benefits of adoption may be most significant for children adopted prior to the age of two.Citation99 However, across ages, youth quickly “catch up” to their community-matched peers physically, while psychological difficulties may take more time.Citation33 These psychological delays are supported by research indicating that there is limited change to the HPA axis dysregulation post-adoption and a slow increase in limbic white matter.Citation14,Citation95,Citation98 Lloyd and BarthCitation32 found that adopted youth continued to have externalizing behavior problems and exhibitive maladaptive behavior patterns. There is no literature exploring whether there are improvements in sleep post-adoption; instead, research has focused on the sleep difficulties that children have at the time of adoption.Citation15,Citation19,Citation25 However, based on that many risk factors disappear post-adoption and that some individuals improve without intervention, it can be hypothesized that some children will see improvement in sleep post-adoption if their neurobiology has not stabilized in a dysfunctional pattern.Citation14,Citation24,Citation99

Discussion

Interest in enhanced sleep as a universal intervention for youth with complex issues is growing. Sleep difficulties can cause impairment in multiple domains, and resolution may improve a child’s functioning. Children of all ages and backgrounds are susceptible to the development of sleep difficulties. However, certain psychosocial stressors increase the likelihood that a child will experience sleep difficulties. Parenting styles, parent psychopathology, abuse, neglect, dangerous neighborhoods, transitioning living situations, and child psychopathology may all increase the likelihood that children will develop sleep difficulties through similar mechanisms seen in populations of youth with psychopathology or trauma exposure.Citation29,Citation30,Citation42 These experiences are more prevalent in adopted youth than their non-adopted counterparts.Citation18,Citation28 Thus, in keeping with adoptive parent report, it is likely that sleep difficulties are a significant complication facing newly formed families post-adoption.

These psychosocial stressors may create concurrent and lasting sleep difficulties for adopted children. While the neurobiology behind sleep regulation is designed to prevent disruption, many of these stressors influence multiple regions of the brain (ie, HPA axis, limbic system).Citation99,Citation104 Thus, the regions responsible for sleep regulation may be disrupted, potentially perpetuating sleep difficulties. The disruptions from psychosocial stressors may become stabilized in the brain through new neural pathways.Citation90 Thus, sleep difficulties stemming from the psychosocial experience prior to and throughout the adoption process may result in long-term sleep difficulties. Further, adopted children are at an increased risk for the development of psychopathology, which may also maintain sleep difficulties and create a vicious cycle of reinforcement.

Future directions and implications

Adoptive parents frequently cite sleep difficulties as areas of concern, and report wanting assistance in helping their children cope with sleep difficulties.Citation20,Citation31 As noted, there is limited research exploring this critical area in adoption. However, there is a growing body of literature on sleep in related populations such as youth with psychopathology, youth experiencing maltreatment, and attachment and parenting styles.Citation42,Citation48,Citation91 This paper describes and integrates aspects of this literature that applies to adopted youth and allows for a theoretical framework to be applied.

As in many areas with a paucity of research, more research needs to be conducted before the model proposed in this paper can be empirically evaluated. First, further research effort is needed to describe the problem more thoroughly. The types of sleep difficulties, how disruptive they are, and the methods families use to address them will provide critical information to researchers and clinicians. Further, it would be useful to explore whether there are factors that moderate or mediate the relation between the adoption process and sleep including adoption process experiences (ie, foster care, family adoption), trauma history, and types of trauma experienced. School performance, social functioning, psychopathology, and family adjustment will all be important outcomes to measure.

After this information has been collected, it will be possible to test sleep interventions targeted at the subpopulations that most need intervention and tailor interventions to their needs. Sleep restriction as a part of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia has been shown to be effective in many populations of children as it works to reset the circadian rhythm and homeostatic system.Citation105 It would be beneficial to test sleep restriction across the unique populations seen in the adoption community (ie, international, intra-family, and inter-family). Additionally, it may be important to examine how to implement sleep restriction across cultures in adoption, which may be particularly important for international adoptions. Other areas for intervention may include sleep hygiene and bedtime routines. As noted, children may experience ineffective parenting around bedtime which increases sleep disturbances.

Finally, there are immediate clinical implications of this model. Adoptive parents regularly request assistance improving their children’s sleep habits and correcting sleep issues.Citation20 Sleep may be an ideal area for clinicians working with adopted children to target. Often treated as a symptom of psychosocial stressors, addressing it more directly may allow for improved functioning and a greater ability to manage other psychosocial stressors. While sleep restriction is a difficult process for both children and parents, it may be an effective way to interrupt the cycle of biopsychosocial disruption and maintenance proposed in this model.

Whether addressed first or as a part of a multifaceted treatment, it is likely that many adopted children would benefit from a more direct approach to treating their sleep difficulties. By using this model as a framework for research and treatment, researchers and clinicians may be able to more effectively conceptualize and treat adopted children’s sleep difficulties and ease the transition into their new family. With a growing number of adoptions in the US every year, it is important to address this concern to improve sleep for millions of children.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial or nonfinancial relationships to disclose in this work. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- El-SheikhMSadehAI. Sleep and development: introduction to the monographMonogr Soc Res Child Dev2015801114

- PoeGRWalshCMBjornessTECognitive neuroscience of sleepProg Brain Res201018511921075230

- CarskadonMATarokhLDevelopmental changes in sleep biology and potential effects on adolescent behavior and caffeine useNutr Rev201472Suppl 1606425293544

- Fernandez-MendozaJVgontzasANCalhounSLInsomnia symptoms, objective sleep duration and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity in childrenEur J Clin Invest201444549350024635035

- GerberLSleep deprivation in children: a growing public health concernNursing20144445054

- GregoryAMCaspiAMoffittTEPoultonRSleep problems in childhood predict neuropsychological functioning in adolescencePediatrics200912341171117619336377

- GoelNRaoHDurmerJSDingesDFNeurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivationSemin Neurol200929432033919742409

- ChapmanDPLiuYPresley-CantrellLRAdverse childhood experiences and frequent insufficient sleep in 5 U.S. states, 2009: a retrospective cohort studyBMC Public Health201313323286392

- LukowskiAFBellMAOn sleep and development: recent advances and future directionsMonogr Soc Res Child Dev201580118219525704743

- ShochatTCohen-ZionMTzischinskyOFunctional consequences of inadequate sleep in adolescents: a systematic reviewSleep Med Rev2014181758723806891

- United States Children’s BureauThe adoption and foster care analysis and reporting system report for 20122013 Available from: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport20.pdfAccessed May 15, 2016

- Child Welfare Information GatewayHow many children were adopted in 2007 and 2008?2011 Available from: https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/adopted0708/Accessed May 15, 2016

- GrotevantHDMcDermottJMAdoption: biological and social processes linked to adaptationAnnu Rev Psychol20146523526524016275

- KossKJHostinarCEDonzellaBGunnarMRSocial deprivation and the HPA axis in early developmentPsychoneuroendocrinology20145011325150507

- TanTXMarfoKDedrickRFPreschool-age adopted Chinese children’s sleep problems and family sleep arrangementsInfant Child Dev2009185422440

- HusseyDLFallettaLEngARisk factors for mental health diagnoses among children adopted from the public child welfare systemChild Youth Serv Rev2012341020722080

- SimmelCBarthRPBrooksDAdopted foster youths’ psychoso-cial functioning: a longitudinal perspectiveChild Fam Soc Work2007124336348

- Child Welfare Information GatewayFinding and using postadoption services2012 Available from: http://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/f_postadoption.cfmAccessed May 16, 2016

- TanTXPreschool-age adopted Chinese girls’ behaviors that were most concerning to their mothersAdopt Q20101313449

- TirellaLGTickle-DegnenLMillerLCBedellGParent strategies for addressing the needs of their newly adopted childPhys Occup Ther Pediatr20123219711021875386

- SimmelCRisk and protective factors contributing to the longitudinal psychosocial well-being of adopted foster childrenJ Emot Behav Disord2007154237249

- CuddihyCDorrisLMinnisHKocovskaESleep disturbance in adopted children with a history of maltreatmentAdopt Foster2013374404411

- DamsteegtRCvan IJzendoornMHOutDBakermans-KranenburgMJTympanic membrane temperature in adopted children associated with sleep problems and pre-adoption living arrangements: an exploratory studyBMC Psychol2014215125520810

- ManneringAMHaroldGTLeveLDLongitudinal associations between marital instability and child sleep problems across infancy and toddlerhood in adoptive familiesChild Dev20118241252126621557740

- RettigMAMcCarthy-RettigKA survey of the health, sleep, and development of children adopted from ChinaHealth Soc Work200631320120716955658

- TirellaLGMillerLCSelf-regulation in newly arrived international adopteesPhys Occup Ther Pediatr201131330131421391835

- BaldwinSGrowth, development, and behavior: confronting the issues of international adoptionJ Ark Med Soc2011107918318521366020

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent PsychiatryFacts for families: foster care2012 Available from: http://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Foster-Care-064.aspxAccessed May 16, 2016

- ConnellCMVanderploegJJFlaspohlerPKatzKHSaundersLTebesJKChanges in placement among children in foster care: a longitudinal study of child and case influencesSoc Serv Rev200680339841825342863

- LawrenceCRCarlsonEAEgelandBThe impact of foster care on developmentDev Psychopathol2006181577616478552

- TininenkoJRFisherPABruceJPearsKCSleep disruption in young foster childrenChild Psychiatry Hum Dev201041440942420221849

- LloydECBarthRPDevelopmental outcomes after five years for foster children returned home, remaining in care, or adoptedChild Youth Serv Rev201133813831391

- PalaciosJRománMCamachoCGrowth and development in internationally adopted children: extent and timing of recovery after early adversityChild Care Health Dev201137228228820666780

- ChristoffersenMNA study of adopted children, their environment, and development: a systematic reviewAdopt Q2012153220237

- DielemanGCHuizinkACTulenJHAlterations in HPA-axis and autonomic nervous system functioning in childhood anxiety disorders point to a chronic stress hypothesisPsychoneuroendocrinology20155113515025305548

- GiannottiFCortesiFFamily and cultural influences on sleep developmentChild Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am200918484986119836692

- GregoryAMCaspiAMoffittTEPoultonRFamily conflict in childhood: a predictor of later insomniaSleep20062981063106716944675

- Lamers-WinkelmanFDe SchipperJCOostermanMChildren’s physical health complaints after exposure to intimate partner violenceBr J Health Psychol201217477178422490127

- TarokhLCarskadonMASleep electroencephalogram in children with a parental history of alcohol abuse/dependenceJ Sleep Res2010191 Pt 216517419735444

- BenhamouISleep disorders of early childhood: a reviewIsr J Psychiatry Relat Sci200037319019611084806

- LeeSRhieSChaeKYDepression and marital intimacy level in parents of infants with sleep onset association disorder: a preliminary study on the effect of sleep educationKorean J Pediatr201356521121723741235

- CecilCAVidingEMcCroryEJGregoryAMDistinct mechanisms underlie associations between forms of childhood maltreatment and disruptive nocturnal behaviorsDev Neuropsychol201540318119926151615

- EpsteinRABoboWVCullMJGatlinDSleep and school problems among children and adolescents in state custodyJ Nerv Ment Dis2011199425125621451349

- KellyRJMarksBTEl-SheikhMLongitudinal relations between parent-child conflict and children’s adjustment: the role of children’s sleepJ Abnorm Child Psychol20144271175118524634010

- BélangerMÈBernierASimardVBordeleauSCarrierJViii. Attachment and sleep among toddlers: disentangling attachment security and dependencyMonogr Soc Res Child Dev201580112514025704739

- CharuvastraACloitreMSafe enough to sleep: sleep disruptions associated with trauma, posttraumatic stress, and anxiety in children and adolescentsChild Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am200918487789119836694

- VaughnBEEl-SheikhMShinNElmore-StatonLKrzysikLMonteiroLAttachment representations, sleep quality and adaptive functioning in preschool age childrenAttach Hum Dev201113652554022011098

- GregoryAMSadehASleep, emotional and behavioral difficulties in children and adolescentsSleep Med Rev201216212913621676633

- AdamEKSnellEKPendryPSleep timing and quantity in ecological and family context: a nationally representative time-diary studyJ Family Psychol2007211419

- ChenTWuZShenZZhangJShenXLiSSleep duration in Chinese adolescents: biological, environmental, and behavioral predictorsSleep Med201415111345135325277663

- ArmstrongJMRuttlePLKleinMHEssexMJBencaRMAssociations of child insomnia, sleep movement, and their persistence with mental health symptoms in childhood and adolescenceSleep201437590190924790268

- NollJGTrickettPKSusmanEJPutnamFWSleep disturbances and childhood sexual abuseJ Pediatr Psychol200631546948015958722

- KeyesMASharmaAElkinsIJIaconoWGMcGueMThe mental health of US adolescents adopted in infancyArch Pediatr Adolesc Med2008162541942518458187

- KotsopoulosSCôtéAJosephLPsychiatric disorders in adopted children: a controlled studyAm J Orthopsychiatry19885846086123265858

- JufferFvan IjzendoornMHBehavior problems and mental health referrals of international adoptees: a meta-analysisJAMA2005293202501251515914751

- LofthouseNGilchristRSplaingardMMood-related sleep problems in children and adolescentsChild Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am200918489391619836695

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders5th edArlington, VAAmerican Psychiatric Association2013

- SarchiaponeMMandelliLCarliVHours of sleep in adolescents and its association with anxiety, emotional concerns, and suicidal ideationSleep Med201415224825424424101

- ZoccolaPMDickersonSSLamSRumination predicts longer sleep onset latency after an acute psychosocial stressorPsychosom Med200971777177519622710

- LeporeSJKliewerWViolence exposure, sleep disturbance, and poor academic performance in middle schoolJ Abnorm Child Psychol20134181179118923315234

- KliewerWLeporeSJExposure to violence, social cognitive processing, and sleep problems in urban adolescentsJ Youth Adolesc201544250751725218396

- SpilsburyJCBabineauDCFrameJJuhasKRorkKAssociation between children’s exposure to a violent event and objectively and subjectively measured sleep characteristics: a pilot longitudinal studyJ Sleep Res201423558559424841836

- UmlaufMGBollandACBollandKATomekSBollandJMThe effects of age, gender, hopelessness, and exposure to violence on sleep disorder symptoms and daytime sleepiness among adolescents in impoverished neighborhoodsJ Youth Adolesc201544251854225070645

- FalbeJDavisonKKFranckleRLSleep duration, restfulness, and screens in the sleep environmentPediatrics20151352e367e37525560435

- MadanskyDEdelbrockCCosleeping in a community sample of 2- and 3-year-old childrenPediatrics19908621972032371094

- WeimerSMDiseTLEversPBOrtizMAWelldaregayWSteinmannWCPrevalence, predictors, and attitudes toward cosleeping in an urban pediatric centerClin Pediatr (Phila)200241643343812166796

- LatzSWolfAWLozoffBCosleeping in context: sleep practices and problems in young children in Japan and the United StatesArch Pediatr Adolesc Med1999153433934610201715

- BorbélyAAA two process model of sleep regulationHum Neurobiol1982131952047185792

- BorbélyAAProcesses underlying sleep regulationHorm Res Paediatr1998493–4114117

- MirmiranMMaasYGAriagnoRLDevelopment of fetal and neonatal sleep and circadian rhythmsSleep Med Rev20037432133414505599

- BasheerRStreckerREThakkarMMMcCarleyRWAdenosine and sleep–wake regulationProg Neurobiol200473637939615313333

- ZeitzerJMControl of sleep and wakefulness in health and diseaseProg Mol Biol Transl Sci201311913715423899597

- BuysseDJGermainAHallMMonkTHNofzingerEAA neurobiological model of insomniaDrug Discov Today Dis Models20118412913722081772

- PerryJCBergamaschiCTCamposRRSilvaAMTufikSInterconnectivity of sympathetic and sleep networks is mediated through reduction of gamma aminobutyric acidergic inhibition in the paraventricular nucleusJ Sleep Res201423216817524283672

- MaesJVerbraeckenJWillemenMSleep misperception, EEG characteristics and autonomic nervous system activity in primary insomnia: a retrospective study on polysomnographic dataInt J Psychophysiol201491316317124177246

- BarclayNLGregoryAMSleep in childhood and adolescence: age-specific sleep characteristics, common sleep disturbances and associated difficultiesCurr Top Behav Neurosci20141633736524170426

- WaterhouseJFukudaYMoritaTDaily rhythms of the sleep-wake cycleJ Physiol Anthropol2012311522738268

- GiannottiFCortesiFSebastianiTOttavianoSCircadian preference, sleep and daytime behaviour in adolescenceJ Sleep Res200211319119912220314

- RothTRoehrsTInsomnia: epidemiology, characteristics, and consequencesClin Cornerstone20035351514626537

- SheaAWalshCMacmillanHSteinerMChild maltreatment and HPA axis dysregulation: relationship to major depressive disorder and post traumatic stress disorder in femalesPsychoneuroendocrinology200530216217815471614

- TeicherMHAndersenSLPolcariAAndersonCMNavaltaCPKimDMThe neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatmentNeurosci Biobehav Rev2003271–2334412732221

- LianYXiaoJLiuYAssociations between insomnia, sleep duration and poor work abilityJ Psychosom Res2015781455125288095

- SuzukiHBeldenACSpitznagelEDietrichRLubyJLBlunted stress cortisol reactivity and failure to acclimate to familiar stress in depressed and sub-syndromal childrenPsychiatry Res2013210257558323876281

- EdmistonEEWangFMazureCMCorticostriatal-limbic gray matter morphology in adolescents with self-reported exposure to childhood maltreatmentArch Pediatr Adolesc Med2011165121069107722147775

- KuhlmanKRGeissEGVargasILopez-DuranNLDifferential associations between childhood trauma subtypes and adolescent HPA-axis functioningPsychoneuroendocrinology20155410311425704913

- ZhangJLamSPLiSXA community-based study on the association between insomnia and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: sex and pubertal influencesJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20149962277228724617708

- HuangZLiangPJiaXAbnormal amygdala connectivity in patients with primary insomnia: evidence from resting state fMRIEur J Radiol20128161288129521458943

- O’ByrneJNBerman RosaMGouinJPDang-VuTTNeuroimaging findings in primary insomniaPathol Biol (Paris)201462526226925129873

- El-SheikhMErathSABagleyEJParasympathetic nervous system activity and children’s sleepJ Sleep Res201322328228823217056

- SalasREGaleaJMGamaldoAAIncreased use-dependent plasticity in chronic insomniaSleep201437353554424587576

- SteineIMHarveyAGKrystalJHSleep disturbances in sexual abuse victims: a systematic reviewSleep Med Rev2012161152521600813

- LaurentHKGilliamKSBruceJFisherPAHPA stability for children in foster care: mental health implications and moderation by early interventionDev Psychobiol20145661406141524889670

- SheridanMDrurySMcLaughlinKAlmasAEarly institutionalization: neurobiological consequences and genetic modifiersNeuropsychol Rev201020441442921042937

- FisherPAManneringAMVan ScoyocAGrahamAMA translational neuroscience perspective on the importance of reducing placement instability among foster childrenChild Welfare2013925936

- KumarABehenMESingsoonsudPMicrostructural abnormalities in language and limbic pathways in orphanage-reared children: a diffusion tensor imaging studyJ Child Neurol201429331832523358628

- PengHLongYLiJHypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning and dysfunctional attitude in depressed patients with and without childhood neglectBMC Psychiatry2014144524548345

- BruceJFisherPAPearsKCLevineSMorning cortisol levels in preschool-aged foster children: differential effects of maltreatment typeDev Psychobiol2009511142318720365

- LaurentHKNeiderhiserJMNatsuakiMNStress system development from age 4.5 to 6: family environment predictors and adjustment implications of HPA activity stability versus changeDev Psychobiol201456334035423400689

- McLaughlinKASheridanMATibuFFoxNAZeanahCHNelsonCA3rdCausal effects of the early caregiving environment on development of stress response systems in childrenProc Natl Acad Sci U S A2015112185637564225902515

- MooreMKirchnerHLDrotarDRelationships among sleepiness, sleep time, and psychological functioning in adolescentsJ Pediatr Psychol200934101175118319494088

- LinWHYiCCUnhealthy sleep practices, conduct problems, and daytime functioning during adolescenceJ Youth Adolesc201544243144625148793

- SimolaPLiukkonenKPitkarantaAPirinenTAronenETPsychosocial and somatic outcomes of sleep problems in children: a 4-year follow-up studyChild Care Health Dev2014401606722774762

- CheeMWChuahLYFunctional neuroimaging insights into how sleep and sleep deprivation affect memory and cognitionCurr Opin Neurol200821441742318607201

- FisherPAVan RyzinMJGunnarMRMitigating HPA axis dysregulation associated with placement changes in foster carePsychoneuroendocrinology201136453153920888698

- PaineSGradisarMA randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behaviour therapy for behavioural insomnia of childhood in school-aged childrenBehav Res Ther2011496–737938821550589