Abstract

Millions of children and adolescents each year are exposed to potentially traumatic events (PTEs), placing them at risk for posttraumatic stress (PTS) disorder symptoms. Medical providers play an important role in the identification and treatment of PTS, as they are typically the initial point of contact for families in the wake of a PTE or during a PTE if it is medically related (eg, injury/illness). This paper offers a review of the literature focused on clinical characteristics of PTS, the assessment and diagnosis of PTS, and current effective treatments for PTS in school-age children and adolescents. The clinical presentation of PTS is often complex as symptoms may closely resemble other internalizing and externalizing disorders. A number of screening and evaluation tools are available for medical providers to assist them in the accurate diagnosis of PTS. Treatment options are available for youth at minimal risk of PTS as well as for those with more intensive needs. Additional training regarding trauma-informed medical care may benefit medical providers. By taking a trauma-informed approach, rooted in a solid understanding of the clinical presentation of PTS in children and adolescents, medical providers can ensure PTS does not go undetected, minimize the traumatic aspects of medical care, and better promote health and well-being.

Introduction

Childhood trauma exposure is unfortunately prevalent. According to a national survey in the USA, 60% of children and adolescents have experienced or witnessed a potentially traumatic event (PTE),Citation1 such as domestic violence, injuries, and natural disasters.Citation2–Citation4 Approximately 30% of youth who are exposed to a PTE develop symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD),Citation5 and an additional subset experience significant, chronic symptoms of posttraumatic stress (PTS). For instance, while PTS resolves for a majority of children and adolescents within 3 months of a potentially traumatic injury, approximately 15%–25% will experience chronic symptoms.Citation6–Citation9 Chronic PTS can adversely affect child health and development and lead to worse functional outcomes.Citation10–Citation14

Empirical evidence indicates that PTS is more likely to go unnoticed and untreated in children and adolescents than adults; this may result from the challenging nature of the expression of PTS in youth (eg, internalizing symptoms that children do not share with adults; adults mistaking externalizing symptoms for oppositional behaviors).Citation15–Citation18 However, early identification of youth at risk for PTS can help reduce morbidity, societal cost, and long-term disability through the implementation of early interventions.Citation19–Citation23 Following exposure to a PTE, many children and families interact with medical providers. Most will report to their primary care provider first for assistance dealing with a PTE.Citation24 As medical providers are typically the first line of defense in the wake of traumatic experiences, it is important that they are well equipped to manage PTS, yet most receive little training.Citation25,Citation26 Although PTS cannot be diagnosed until symptoms have persisted for at least 1 month, significant symptoms may emerge shortly after the PTE, providing an opportunity for providers to support and monitor these children and adolescents. Developed specifically for medical providers practicing within the USA, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) created guidelines for the management of youth with PTS. Regarding assessment guidelines, the AACAP recommends that medical providers routinely ask questions about PTEs and possible PTS, conduct a formal evaluation if symptoms are endorsed, and pay particular attention to possible differential diagnoses. Furthermore, the AACAP guidelines indicate the treatment approach should be developed based on consideration of the severity and degree of impairment of the symptoms and should incorporate appropriate interventions for comorbid disorders. Psychotherapy is recommended as the first-line treatment, although the AACAP practice parameters also specify that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as well as medications other than SSRIs may be used for treatment. The use of therapies involving binding or restriction (eg, rebirthing therapies) is not supported.Citation27

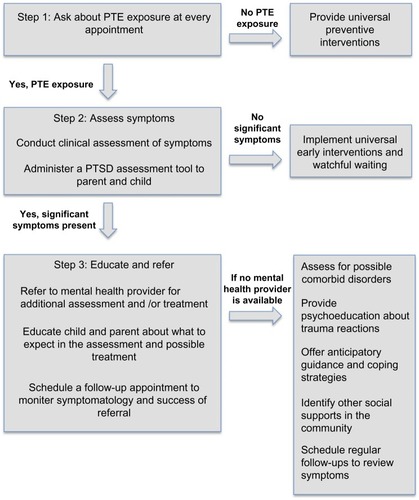

Thus, in line with the aforementioned AACAP guidelines, the purpose of this review is to provide information to strengthen medical providers’ knowledge about assessment and treatment for PTS following trauma exposure in school-age children and adolescents. The information presented in this paper is focused for US-based practitioners; however, much of the information is relevant to those in other developed countries as long as cultural differences are considered. For providers practicing in countries with fewer resources, youth responses to treatment and guidelines post-PTE may differ from research and recommendations presented here. The following narrative review includes the clinical characteristics of PTS, assessment and diagnosis of PTS, and current effective treatments for PTS in school-age children and adolescents ( provides a summary of specific steps for medical providers).

Clinical presentation of childhood PTSD

Recognizing PTSD symptom presentation in primary care or other medical settings can promote recovery and healthy development in children and adolescents exposed to PTEs. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) differentiates PTS symptoms across four distinct symptom clusters, providing an initial roadmap for identifying those who may be struggling with such symptoms. DSM-5 accounts for developmental considerations with modified criteria for youth older than 6 years. lists criteria and examples of how symptoms may present in school-age children and adolescents. Regardless of whether their symptoms meet full diagnostic criteria, high levels of distress and functional impairment can occur amidst symptoms that do not meet diagnostic threshold of PTSD.Citation28–Citation30 Children and adolescents who are struggling from significant PTSD symptoms but who do not qualify for a diagnosis for PTSD may benefit from consideration of PTS from a dimensional perspective (ie, severity of symptoms and subsequent impairment); this offers flexibility in recognizing symptoms that require clinical attention apart from diagnostic status.Citation31

Table 1 PTS and examples of manifestation in school-age children and adolescents

Co-occurring symptoms and comorbidities: initial recognition of PTS

In children and adolescents, PTEs and subsequent PTS may manifest in the form of internalizing and externalizing symptoms that do not fit neatly within the PTSD diagnostic criteria. Such symptoms may well originate from and represent underlying PTS. For example, symptoms may devolve into anxiety about separating from one’s caregiver,Citation32 shame, and/or guilt.Citation33 Alternatively, or in addition, youth may present with low frustration tolerance or seem as though a breaking point is imminent at any moment.Citation34 Thus, it is not surprising that significant rates of comorbidities are evident between PTS and the following disorders: 1) attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),Citation35 as hyperarousal can present as hyperactivity and impulsivity and intrusive thoughts can impair attention and concentration;Citation36,Citation37 2) externalizing disorders such as conduct disorder (CD) or oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), as youth with PTS may exhibit temper outbursts, defiance, hostility, and aggression due to underlying symptoms of irritability, extreme avoidance, and hypersensitivity;Citation36 3) obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), a disorder characterized by recurrent, intrusive thoughts, similar to the reexperiencing symptoms of PTS;Citation36 4) anxiety disorders, as the avoidance, irritability, arousal, and anxiety associated with panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder are also characteristic of PTS;Citation36 and 5) traumatic brain injury (TBI), as youth who have incurred a TBI may report somatic, mood, and cognitive changes that overlap with some symptoms of PTS (eg, irritability, concentration difficulties).Citation36 While there may be some overlap between PTS and other disorders, providers ought to take caution in making these diagnoses to determine whether PTS are causing or contributing to the observed behaviors.

Consideration for complex trauma: consistently inconsistent clinical presentation

Among children and adolescents who are chronically exposed to PTEs and/or maltreatment, symptoms may be more diffuse and difficult to categorize. The effects of chronic trauma can cause changes in neurobiological development as well as the ability to integrate sensory, emotional, and cognitive information; children rarely demonstrate a discrete change in behavior, as occurs following an acute PTE.Citation38 Complex trauma is defined as severe stressors that 1) are repetitive or prolonged, 2) involve harm or abandonment by caregivers or other ostensibly responsible adults, and 3) occur at developmentally vulnerable times in the victim’s life, such as early childhood or adolescence.Citation39

While complex trauma disorders are beyond the scope of this paper, it is important to note that children and adolescents who are suspected of having experienced chronic trauma exposure and/or maltreatment greatly benefit from expert assessment and treatment, and generally should be referred for a psychological evaluation if they are reporting symptoms.Citation40

Assessment of PTS in school-age children and adolescents

Initial assessment process

Medical providers play an important role in the initial screening process for PTS given that they are more likely to come into contact with children and adolescents following PTEs than mental health professionals.Citation41 They can effectively screen for symptoms by inquiring about coping mechanisms and youths’ appraisals of the event to better understand who may be at risk for PTS.Citation42 As parental report may be influenced by parents’ own symptomatology, it is also critical to obtain children’s and adolescents’ self-reports in addition to parents’ perspectives whenever possible.Citation43 In addition to eliciting symptoms directly from youths and parents during clinical examinations, a number of screening measures for PTS have been developed by medical professionals. Such instruments are typically brief and easy to administer, making them a viable option for use in an acute care or primary care setting. The Screening Tool for Early Predictors of PTSD (STEPP), the UCLA Posttraumatic Stress Disorder – Reaction Index (UCLA-PTSD-RI), and the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSCC) are evidence-based screening instruments. The STEPP is a tool developed for use in the emergency department following pediatric injury and is based on early physiological reactions (eg, heart rate) and early psychological responses to the trauma.Citation7 The UCLA-PTSD-RI is a brief measure assessing exposure to traumatic exposure and the impact of those experiences,Citation44 and the TSCC is self-report measure designed to elicit information regarding trauma-related symptoms.Citation45,Citation46

Evaluating children and adolescents for PTS in an acute care or primary care setting can be difficult for a variety of reasons. First, PTS tends to be more unfamiliar to youths and parents than other more observable disorders, such as ADHD, depression, and OCD.Citation47 Furthermore, parents do not always have a good understanding of factors that predispose their children to developing PTS. For instance, parents may believe that their children only develop PTS after a severe trauma, while research has clearly demonstrated that subjective perceptions of threat regarding the PTE or PTE consequences are better predictors of PTS.Citation48 Additionally, some parents may minimize or deny their children’s symptoms, which may be a function of their own PTS.Citation18,Citation49 Moreover, avoidance symptoms may complicate the screening process as parents or youths who do not want to think about the PTE may try to ignore symptoms.Citation47 Finally, the sheer number of potential differential or comorbid diagnoses adds complexity to the process of recognizing and accurately identifying PTS, underlying the importance of obtaining a thorough history and description of symptoms as well as assessing sociocontextual factors that may influence symptom presentation and functioning.

Should clinical report and the administration of a screening measure raise significant concerns or questions, a referral to a mental health provider can facilitate a more thorough assessment. Upon making a referral, medical providers should expect mental health providers to conduct thorough assessments including multi-informant report. Mental health providers will often include information collected and documented by school personnel (eg, teachers, administrators, guidance counselors), community members (eg, coaches, religious leaders), medical records, and police reports, when applicable.

If the child or adolescent is unable to access mental health services, medical providers may similarly consider reaching out to school personnel, community members, and obtaining medical and/or police reports to obtain more information to inform their trauma-related diagnosis. In addition, if the responsibility of conducting a more thorough assessment (ie, beyond screening) falls on the medical providers, there are a number of commonly employed and psychometrically sound measures designed to assess PTS among children and adolescents. lists a summary of key features and considerations related to each of these tools.

Table 2 Assessment tools that include PTSD

Supporting school-age children and adolescents with PTS

Providers can implement preventive interventions to promote child and adolescent well-being even before experiencing a PTE. Preventive interventions can be considered a universal precaution, but may be especially helpful for youth who are at risk for trauma due to life situations, have a history of difficulty adjusting to stressful events, or are suspected of being victimized without a report of a PTE. According to Pfefferbaum et al,Citation50 preventive interventions often include teaching coping skills, increasing affect awareness and modulation, future safety planning, and offering psychoeducation about trauma reactions. Children and adolescents who have experienced a PTE and have symptoms of PTS should receive support based on the intensity of symptoms they are experiencing, as determined by the assessment process.

Children and adolescents with minimal symptomatology following a PTE

For all children and adolescents who have experienced a PTE, a number of early intervention strategies are available to medical providers to promote recovery and resilience in the aftermath of trauma. On the basis of the results of a recent meta-analysis, the following are effective, common elements found in most early interventions: psychoeducation about typical posttraumatic reactions, promotion of coping strategies, and enhancement of social support.Citation51 Prior to lengthy interventions or assessments for youth without impairing symptoms immediately following a PTE, Kassam-Adams et alCitation42 recommend taking a “watchful waiting” approach. These strategies require minimal training and time and are cost less to implement, making them feasible for use within the health care system. For example, providers can offer basic education regarding PTS, encourage positive coping efforts, and monitor symptoms. provides a list of resources available to medical providers.

Table 3 Resources for medical providers

Children and adolescents with impairing PTS

For children and adolescents exhibiting more severe and/or persistent PTS, referrals should be made to clinicians who are trained to treat children with PTS. Understanding the basics of these treatments can help medical providers prepare their patients for treatment and follow-up with their patients over time. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) has the most empirical support as an efficacious treatment approach.Citation52–Citation55 There is also evidence to support the utility of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy (EMDR) and preliminary evidence for pharmacological treatments.Citation56–Citation58 Other treatments including cognitive therapy, play therapy, psychological first aid, and multisystemic therapy for PTS in children are listed briefly in .

Table 4 Treatments for PTS

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy

TF-CBT can be particularly helpful for children and adolescents who have experienced one or more PTEs.Citation53,Citation59–Citation62 It is based on the principles of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which focus on examining and changing the relationships among cognitions, feelings, and behaviors.Citation63–Citation65 Targeting change in negative cognitions and the beliefs that influence these cognitions helps children modify their patterns of thinking and behavior to enhance coping. For example, children are encouraged to examine their unhelpful beliefs such as “I will never feel normal again”, and find alternative, positive ways of thinking by generating positive self-statements and developing coping strategies. Another core aspect of treatment is exposure therapy, where children and adolescents are confronted with trauma reminders in an effort to gradually reduce avoidance of feared stimuli.Citation63–Citation65 The efficacy of TF-CBT has been demonstrated for youth who have experienced sexual abuse,Citation53,Citation59,Citation61 natural disasters,Citation66 accidental injury,Citation60 and single-incident trauma, including violence.Citation62 TF-CBT utilizes four primary principles of CBT to decrease PTS including psychoeducation and setting goals, coping skills, exposure and cognitive restructuring, and relapse prevention. TF-CBT differs from traditional CBT in that it focuses on the trauma experience and targets decreasing PTS.Citation53 It may be helpful for providers to keep in mind that while the exposure component of treatment is effective, it can be distressing for youth because it requires them to confront upsetting trauma reminders. Children and adolescents may need extra support from their parents and possibly medical providers during this period of time.

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy

Results from several meta-analyses suggest EMDR is comparable to other empirically supported treatments for PTS, including exposure therapy.Citation56–Citation58 EMDR has been effective in treatment of PTS in children and adolescents who experienced sexual abuse,Citation67 disasters,Citation68 interpersonal violence,Citation69 and motor-vehicle accidents.Citation70 The theory behind EMDR is that PTS results from insufficient processing or integration of sensory, cognitive, and affective components of the traumatic memory. During EMDR, the therapist moves his or her finger in front of the child’s eyes in a lateral movement to elicit saccadic eye movements. The eye movements are thought to facilitate information processing and integration.Citation71 Simultaneously, the child conducts imaginal exposure of the traumatic memory. The process occurs repeatedly until distress related to the traumatic memory subsides.Citation72 However, EMDR lacks an empirically validated model for explaining the mechanism through which the eye movements are effective. It has been suggested that it is the exposure portion of the treatment that works to improve children’s symptoms rather than the rapid eye movements themselves.Citation73,Citation74 Similar to the exposure components of TF-CBT, participating in EMDR treatment can be distressing for children and adolescents at times as they are required to process trauma-related information. Medical providers can fulfill a supportive role for children and families during the treatment period by helping families know what to expect and communicating any concerns to the child’s mental health provider.

Psychopharmacological treatments

Research investigating psychopharmacological treatments for PTS in children and adolescents is limited.Citation75 However, the notion that SSRIs may be an effective treatment option in combination with psychological treatment has garnered recent attention.Citation76,Citation77 Tareen et alCitation78 posit that SSRIs may be beneficial for youths because of their success with adults. While evidence suggests that SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressants, α- and β-aderenergic blocking agents, anxiolytics, antipsychotics, and anticonvulsants successfully treat PTS in adults,Citation79–Citation83 these findings cannot be generalized to children and adolescents due to developmental neurobiological differences.Citation84 Huemer et al’sCitation75 review provides a more detailed explanation of psychopharmacological treatments for youth with PTS. When prescribing medications to treat PTS in children, practitioners also need to be sure that they are up-to-date on ever-changing policies of regulatory agencies. More research is needed to understand how to best support youth with psychopharmacological treatments following trauma. While nonpharmacological approaches (ie, therapy) treatment is the first line of defense for children and adolescents with significant PTS, mental health providers and medical providers may need to collaborate to explore the possibility of psychopharmacological treatment if the child or adolescent continues to experience high levels of distress and/or symptoms that interfere with functioning.

Conclusion

Medical providers play a key role in supporting school-age children and adolescents who have experienced a PTE. Exposure to PTEs place youth at risk for developing PTS, which is related to worse health and functional outcomes.Citation85 The clinical presentation of PTS in school-age children and adolescents is complex and may include additional internalizing and externalizing symptoms or comorbid disorders. Screening and evaluation tools can help medical providers in their evaluation of which youths are at risk for significant PTS. To provide the best care for children and adolescents who have experienced trauma, providers may consider seeking additional training in delivering medical care from a trauma-informed approach. By understanding the clinical presentation of PTS, providers can help support youth at the appropriate level of care by either monitoring symptoms over time, providing basic education and supporting coping, or referring them for a more thorough evaluation and treatment by a mental health provider (). In considering trauma exposure and symptoms in pediatric patients, medical providers can better optimize pediatric health outcomes.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FinkelhorDOrmrodRKTurnerHALifetime assessment of poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youthChild Abuse Negl20093340341119589596

- McDonaldRJourilesENRamisetty-MiklerSCaetanoRGreenCEEstimating the number of American children living in partner-violent familiesJ Fam Psychol200620113714216569098

- GrossmanDThe history of injury control and the epidemiology of child and adolescent injuriesFuture Child2000101235210911687

- PronczukJSurduSChildren’s environmental health in the twenty first centuryAnn N Y Acad Sci20081140114315418991913

- KesslerRSonnegaABrometEHughesMNelsonCPosttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity SurveyArch Gen Psychiatry199552104810607492257

- Kassam-AdamsNWinstonFKPredicting child PTSD: the relationship between acute stress disorder and PTSD in injured childrenJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200443440341115187800

- WinstonFKKassam-AdamsNGarcia-EspañaFIttenbachRCnaanAScreening for risk of persistent posttraumatic stress in injured children and their parentsJAMA2003290564364912902368

- La GrecaAMLaiBSLlabreMMSilvermanWKVernbergEMPrinsteinMJChildren’s postdisaster trajectories of PTS symptoms: predicting chronic distressChild Youth Care Forum201342435136924683300

- Miller-GraffLEHowellKHPosttraumatic stress symptom trajectories among children exposed to violenceJ Trauma Stress2015281172425644072

- CopelandWEKeelerGAngoldACostelloEJTraumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhoodArch Gen Psychiatry200764557758417485609

- ZatzickDFJurkovichGJFanM-YAssociation between post-traumatic stress and depressive symptoms and functional outcomes in adolescents followed up longitudinally after injury hospitalizationArch Pediatr Adolesc Med2008162764264818606935

- FurrJMComerJSEdmundsJMKendallPCDisasters and youth: a meta-analytic examination of posttraumatic stressJ Consult Clin Psychol201078676521114340

- La GrecaAMSilvermanWKTreatment and prevention of posttraumatic stress reactions in children and adolescents exposed to disasters and terrorism: what is the evidence?Child Development Perspectives200931410

- La GrecaAMUnderstanding the psychological impact of terrorism on youth: moving beyond posttraumatic stress disorderClin Psychol Sci Pract2007143219223

- DavidsonJRRecognition and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorderJ Am Med Assoc20012865584588

- DavissWBRacusinRFleischerAMooneyDFordJMcHugoGAcute stress disorder symptomatology during hospitalization for pediatric injuryJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200039556957510802974

- ScheeringaMSZeanahCHCohenJAPTSD in children and adolescents: toward an empirically based algorithmDep and Anx2011289770782

- de VriesAPKassam-AdamsNCnaanASherman-SlateEGallagherPRWinstonFKLooking beyond the physical injury: posttraumatic stress disorder in children and parents after pediatric traffic injuryPediatrics199910461293129910585980

- ZieglerMFGreenwaldMHDeGuzmanMASimonHKPosttraumatic stress responses in children: awareness and practice among a sample of pediatric emergency care providersPediatrics200511551261126715867033

- ZatzickDFKangS-MKimSYPatients with recognized psychiatric disorders in trauma surgery: incidence, inpatient length of stay, and costJ Trauma Acute Care Surg2000493487495

- DrotarDPromoting comprehensive care for children with chronic health conditions and their families: introduction to the special issueChild Serv Soc Pol Res Pract200144157163

- KazakAEComprehensive care for children with cancer and their families: a social ecological framework for guiding research, practice, and policyChild Serv Soc Pol Res Pract200144217233

- ZatzickDFJurkovichGJGentilelloLWisnerDRivaraFPPosttraumatic stress, problem drinking, and functional outcomes after injuryArch Surg2002137220020511822960

- SchappertSMRechsteinerEAAmbulatory Medical Care Utilization Estimates for 2006Hyattsville, MDDepartment of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics2008

- DavidsonEJSilvaTJSofisLAGanzMLPalfreyJSThe doctor’s dilemma: challenges for the primary care physician caring for the child with special health care needsAmbul Pediatr20022321822312014983

- LeslieLKSarahRPalfreyJSChild health care in changing timesPediatrics199810137467529544178

- CohenJABuksteinOWalterHPractice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorderJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry201049441443020410735

- CarrionVGKletterHPosttraumatic stress disorder: shifting toward a developmental frameworkChild Adolesc Psychiatry Clin N Am2012213573591

- CarrionVGWeemsCFRayRReissALToward an empirical definition of pediatric PTSD: The phenomenology of PTSD symptoms in youthJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200241216617311837406

- PynoosRSteinbergALayneCMBriggsEOstrowskiSFairbankJDSM-V PTSD diagnostic criteria for children and adolescents: a developmental perspective and recommendationsJ Trauma Stress200922539139819780125

- Broman-FulksJJRuggieroKJGreenBASmithDWHansonRFKilpatrickDGThe latent structure of PTSD among adolescentsJ Trauma Stress20092214615219319918

- DykmanRAMcPhersonBAckermanPTInternalizing and externalizing characteristics of sexually and/or physically abused childrenIntegr Physiol Behav Sci199732162839105915

- KletterHWeemsCFCarrionVGGuilt and posttraumatic stress symptoms in child victims of interpersonal violenceClin Child Psychol Psychiatry2009141171183

- SchoreAAffect Dysregulation and Disorders of the SelfNew York, NYNorton2003

- KesslerRAdlerLBarkleyRThe prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey ReplicationAm J Psychiatry2006163471672316585449

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders5th edArlington, VAAmerican Psychiatric Publishing2013

- GlodCATeicherMHRelationship between early abuse, posttraumatic stress disorder, and activity levels in prepubertal childrenJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry19963510138413938885593

- FordJDNeurobiological and developmental researchTreating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders: An Evidence-based GuideNew York, NYNorton20093158

- FordJCourtoisCADefining and understanding complex trauma and-complex traumatic stress disordersCourtoisCAFordJDTreating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders: An Evidence-based GuideNew York, NYNorton20091330

- CloitreMStolbachBCHermanJLA developmental approach to complex PTSD: childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexityJ Trauma Stress200922539940819795402

- CohenJAKelleherKJMannarinoAPIdentifying, treating, and referring traumatized children: the role of pediatric providersArch Pediatr Adolesc Med2008162544745218458191

- Kassam-AdamsNMarsacMLHildenbrandAKWinstonFKPosttraumatic stress following pediatric injury: update on diagnosis, risk factors, and interventionJ Am Med Assoc20131671211581165

- Kassam-AdamsNGarcia-EspañaFMillerVAWinstonFKParent-child agreement regarding children’s acute stress: the role of parent acute stress reactionsJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200645121485149317135994

- SteinbergAMBrymerMJDeckerKBPynoosRSThe University of California at Los Angeles post-traumatic stress disorder reaction indexCurr Psychiatry Rep2004629610015038911

- BriereJTrauma Symptom Checklist for ChildrenOdessa FLPsychological Assessment Resources1996

- BriereJJohnsonKBissadaAThe trauma symptom checklist for young children (TSCYC): reliability and association with abuse exposure in a multi-site studyChild Abuse Negl20012581001101411601594

- CohenJAScheeringaMSPosttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis in children: challenges and promisesDialogues Clin Neurosci20091119119432391

- TrickeyDSiddawayAPMeiser-StedmanRSerpellLFieldAPA meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescentsClin Psychol Rev201232212213822245560

- WinstonFKKassam-AdamsNVivarelli-O’NeillCAcute stress disorder symptoms in children and their parents after pediatric traffic injuryPediatrics20021096e90e9012042584

- PfefferbaumBVarmaVNitiemaPNewmanEUniversal preventive interventions for children in the context of disasters and terrorismChild Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am201423363382

- KramerDNLandoltMACharacteristics and efficacy of early psychological interventions in children and adolescents after single trauma: a meta-analysisEur J Psychotraumatol20112

- CohenJAMannarinoAPA treatment outcome study for sexually abused preschool children: initial findingsJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry19963542508567611

- CohenJADeblingerEMannarinoAPSteerRAA multisite randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptomsJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200443439340215187799

- KowalikJWellerJVenterJDrachmanDCognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder: a review and meta-analysisJ Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry201142340541321458405

- SilvermanWKOrtizCDViswesvaranCEvidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic eventsJ Clin Child Adolesc Psychol200837115618318444057

- BissonJIEhlersAMatthewsRPillingSRichardsDTurnerSPsychological treatments for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta-analysisBr J Psychiatry200719029710417267924

- BradleyRGreeneJRussEDutraLWestenDA multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSDAm J Psychiatry2005162221422715677582

- SeidlerGHWagnerFEComparing the efficacy of EMDR and trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of PTSD: a meta-analytic studyPsychol Med200636111515152216740177

- DeblingerEMannarinoAPCohenJASteerRAA follow-up study of a multisite, randomized, controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptomsJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200645121474148417135993

- CobhamVEMarchSDe YoungAInvolving parents in indicated early intervention for childhood PTSD following accidental injuryClin Child Fam Psychol Rev201215434536322983482

- CohenJAMannarinoAPKnudsenKTreating sexually abused children: 1 year follow-up of a randomized controlled trialChild Abuse Negl200529213514515734179

- NixonRDSterkJPearceAA randomized trial of cognitive behavior therapy and cognitive therapy for children with posttraumatic stress disorder following single-incident traumaJ Abnorm Child Psychol201240332733721892594

- RothbaumBOMeadowsEAResickPAFoyDWCognitive- behavioral therapyFoaEBKeaneTMFriedmanMJEffective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress StudiesNew York, NYGuilford Press2000320325

- BriereJScottCPrinciples of Trauma Therapy: A Guide to Symptoms, Evaluation, and TreatmentThousand Oaks, CASage Publications2012

- FreemanAClinical Applications of Cognitive TherapyNew York, NYSpringer2004

- CohenJAJaycoxLHWalkerDWMannarinoAPLangleyAKDuClosJLTreating traumatized children after Hurricane Katrina: project Fleur-de LisClin Child Fam Psychol Rev2009121556419224365

- JaberghaderiNGreenwaldRRubinAZandSODolatabadiSA comparison of CBT and EMDR for sexually-abused Iranian girlsClin Psychol Psychother2004115358368

- de RoosCGreenwaldRden Hollander-GijsmanMNoorthhoornEvan BuurenSde JonghAA randomized comparison of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) in disaster-exposed childrenEur J Psycho-traumatol20112

- JareroIRoque-LopezSGomezJThe provision of an EMDR-based multicomponent trauma treatment with child victims of severe interpersonal traumaJ EMDR Pract Res2013711728

- KempMDrummondPMcDermottBA wait-list controlled pilot study of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for children with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms from motor vehicle accidentsClin Child Psychol Psychiatry201015152519923161

- ShapiroFEye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and the anxiety disorders: clinical and research implications of an integrated psychotherapy treatmentJ Anxiety Disord1999131356710225500

- ShapiroFEye movement desensitization: a new treatment for posttraumatic stress disorderJ Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry1989202112172576656

- GunterRWBodnerGEEMDR works … but how? Recent progress in the search for treatment mechanismsJ EMDR Pract Res200933161168

- PerkinsBRRouanzoinCCA critical evaluation of current views regarding eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): clarifying points of confusionJ Clin Psychol2002581779711748598

- HuemerJErhartFSteinerHPosttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: a review of psychopharmacological treatmentChild Psychiatry Hum Dev201041662464020567898

- KeeshinBRStrawnJRPsychological and pharmacologic treatment of youth with posttraumatic stress disorderChild Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am201423399411

- CohenJAMannarinoAPPerelJMStaronVA pilot randomized controlled trial of combined trauma-focused CBT and sertraline for childhood PTSD symptomsJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200746781181917581445

- TareenAGarraldaMEHodesMPost-traumatic stress disorder in childhoodArch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed200792116

- AldermanCPCondonJTGilbertALAn open-label study of mirtazapine as treatment for combat-related PTSDAnn Pharmacother2009437–81220122619584388

- BauerMSLeeALiMBajorLRasmussonAKazisLEOff-label use of second generation antipsychotics for posttraumatic stress disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs: time trends and sociodemographic, comorbidity, and regional correlatesPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf2014231778623996688

- NaylorJCDolberTRStraussJLA pilot randomized controlled trial with paroxetine for subthreshold PTSD in Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom era veteransPsychiatry Res2013206231832023276723

- TarsitaniLDe SantisVMistrettaMTreatment with β-blockers and incidence of posttraumatic stress disorder after cardiac surgery: a prospective observational studyJ Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth201226226526922051417

- TuckerPSmithKLMarxBJonesDMirandaRJrLensgrafJFluvoxamine reduces physiologic reactivity to trauma scripts in posttraumatic stress disorderJ Clin Psychopharmacol200020336737210831026

- PervanidouPBiology of posttraumatic stress disorder in childhood and adolescenceJ Neuroendocrinol200820563263818363804

- KenardyJALe BrocqueRHendrikzJKIselinGAndersonVMcKinlayLImpact of posttraumatic stress disorder and injury severity on recovery in children with traumatic brain injuryJ Clin Child Adolesc Psychol201241151422233241

- SilvermanWKAlbanoAThe Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children-IV (Child and Parent Versions)San Antonio, TXPsychological Corporation1996

- Meiser-StedmanRSmithPGlucksmanEYuleWDalgleishTParent and child agreement for acute stress disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and other psychopathology in a prospective study of children and adolescents exposed to single-event traumaJ Abnorm Child Psychol200735219120117219079

- AngoldACostelloEJThe child and adolescent psychiatric assessment (CAPA)J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry2000391394810638066

- CostelloEJAngoldAMarchJFairbankJLife events and post-traumatic stress: the development of a new measure for children and adolescentsPsychol Med1998286127512889854269

- FletcherKChildhood PTSD interview – child formCarlsonEBMeasurement of Stress, Trauma, and AdaptationLutherville, MDSidran Press19978789

- WolfeVVGentileCMichienziTSasLWolfeDAThe children’s impact of traumatic events scake: a measure of post-sexual abuse PTSD symptomsBehav Assessment199113359383

- ChaffinMShultzSKPsychometric evaluation of the children’s impact of traumatic events scale-revisedChild Abuse Negl200125340141111414398

- WolfeVVMeasuring post-traumatic stress disorder: the children’s impact of traumatic events scale-revisedAPSAC Advisor1996922526

- CrouchJLSmithDWEzellCESaundersBEMeasuring reactions to sexual trauma among children: comparing the children’s impact of traumatic events scale and the trauma symptom checklist for childrenChild Maltreat199943255263

- SaighPYaskiAEOberfieldRAThe children’s PTSD inventory: development and reliabilityJ Trauma Stress200030369380

- YasikAESaighPAOberfieldRAGreenBHalamandarisPMcHughMThe validity of the children’s PTSD inventoryJ Trauma Stress20011418194

- NaderKONewmanEWeathersFKaloupekDGKrieglerJABlakeDDNational Center for PTSD Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for Children and Adolescents (CAPS-CA) Interview BookletLos Angeles, CAWestern Psychological2004

- NewmanEMcMackinRMorrisseyCErwinBAddressing PTSD and trauma-related symptoms among criminally involved male adolescentsStresspoints1997117

- ReichWDiagnostic interview for children and adolescents (DICA)J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200039596610638068

- EzpeletaLde la OsaNDomenechJMNavarroJBLosillaJMJudezJDiagnostic agreement between clinicians and the diagnostic interview for children and adolescents (DICA-R) in an outpatient sampleJ Child Psychol Psychiatry1997384314409232488

- ReichWCottlerLMcCallumKCorwinDVanEerdeweghMComputerized interviews as a method of assessing psychopathology in childrenCompr Psychiatry199536140457705086

- KaufmanJBirmaherBBrentDSchedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-aged children – present and lifetime version (KSADS-PL): initial reliability and validity dataJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry1997369809889204677

- ArmstrongJGPutnamFWCarlsonEBLiberoDZSmithSRDevelopment and validation of a measure of adolescent dissocation: the adolescent dissociative experiences scaleJ Nerv Ment Dis199718584914979284862

- BrunnerRParzerPSchuldVReschFDissociative symptomatology and traumatogenic factors in adolescent psychiatry patientsJ Nerv Ment Dis2000188717710695834

- SmithSRCarlsonEBReliability and validity of the adolescent dissociative experiences scaleDissociation199692125129

- FoaEBJohnsonKFeenyNCTreadwellKRThe child PTSD symptom scale: a preliminary examination of its psychometric propertiesJ Clin Child Psychol200130337638411501254

- ElliotDMBriereJForensic sexual abuse evaluations of older children: disclosures and symptomatologyBehav Sci Law199412261277

- EvansJJBriereJBoggianoAKBarrettMReliability and validity of the trauma symptom checklist for children in a normal samplePaper presented at: San Diego Conference on Responding to Child MaltreatmentSan Diego, CA1994

- LanktreeCBGilbertAMBriereJMulti-informant assessment of maltreated children: Convergent and discriminant validity of the TSCC and TSCYCChild Abuse Negl200832662162518584866

- SingerMIAnglinTMSongLYLunghoferLAdolescents’ exposure to violence and associated symptoms of psychological traumaJ Am Med Assoc1995273477482

- WolpawJMFordJDNewmanEDavisJLBriereJTrauma symptom checklist for childrenGrissoTVincentGSeagraveDHandbook of Mental Health Screening and Assessment in Juvenile JusticeNew York, NYGuilford2005152165

- PynoosRRodriguezNSteinbergAStuberMLFrederickCThe UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV (Revision 1)Los Angeles, CAUCLA Trauma Psychiatry Program1998

- SteinbergAMBrymerMJKimSPsychometric properties of the UCLA PTSD reaction index: part IJ Trauma Stress20132611923417873

- PutnamFWHelmersKTrickettPDevelopment, reliability, and validity of a child dissociation scaleChild Abuse Negl1993177317418287286

- OhanJMyersKCollettBTen-year review of rating scale. IV: scales assessing trauma and its effectsJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200241121401142212447027

- PutnamFWPetersonGFurther validation of the child dissociative checklistDissociation199474204211

- WherryJNJollyJBFeldmanJAdamBManjanathaSThe child dissociative checklist: preliminary findings of a screening measureJ Child Sex Abus1994335166

- SaylorCFSwensonCCReynoldsSSTaylorMThe pediatric emotional distress scale: a brief sceening measure for young children exposed to traumatic eventsJ Clin Child Psychol1999281708110070608

- SpilsburyJCDrotarDBurantCFlanneryDCreedenRFriedmanSPsychometric properties of the pediatric emotional distress scale in a diverse sample of children exposed to interpersonal violenceJ Clin Child Adolesc Psychol200534475876416232072

- WeathersFFordJPsychometric review of PTSD Checklist (PCL-C, PCL-S, PCL-M, PCL-PR)StammBMeasurement of Stress, Trauma, and AdaptationLutherville, MDSidran Press1996250251

- DavissWBMooneyDRacusinRFordJFleischerAMcHugoGPredicting posttraumatic stress after hospitalization for pediatric injuryJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200039557658310802975

- NilssonDGustafssonPESvedinCGThe psychometric properties of the trauma symptom checklist for young children in a sample of Swedish childrenEur J Psychotraumatol20123

- StuberMLSchneiderSKassam-AdamsNKazakAESaxeGThe Medical Traumatic Stress ToolkitCNS Spectr2006110213714216520691

- MarsacMLKassam-AdamsNHildenbrandAKKohserKLWinstonFKAfter the injury: initial evaluation of a web-based intervention for parents of injured childrenHealth Educ Res201126111220858769

- CoxCMKenardyJAHendrikzJKA randomized controlled trial of a web-based early intervention for children and their parents following unintentional injuryJ Pediatr Psychol201035658159219906829

- Kassam-AdamsNSchneiderSKazakAEHealth Care Toolbox: Your Guide to Helping Children and Families Cope with Illness and InjuryPhiladelphia, PACenter for Pediatric Traumatic Stress2010

- The National Child Traumatic Stress NetworkPsychological First Aid72006

- ForbesDFletcherSWolfgangBPractitioner perceptions of skills for psychological recovery: a training programme for health practitioners in the aftermath of the Victorian bushfiresAust N Z J Psychiatry201044121105111121070106

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network Core Curriculum Task Force12 Core Concepts: Concepts for Understanding Traumatic Stress Responses in Children and Families2007

- EhlersAMayouRBryantBCognitive predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder in children: results of a prospective longitudinal studyBehav Res Ther200341111012488116

- Meiser-StedmanRTowards a cognitive–behavioral model of PTSD in children and adolescentsClin Child Fam Psychol Rev20025421723212495267

- SmithPYuleWPerrinSTranahTDalgleishTClarkDMCognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD in children and adolescents: a preliminary randomized controlled trialJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry20074681051106117667483

- OgawaYChildhood trauma and play therapy intervention for traumatized childrenJ Prof Counsel Pract Theory Res200432119

- RyanVNeedhamCNon-directive play therapy with children experiencing psychic traumaClin Child Psycholo Psychiatry200163437453

- WilsonKRyanVPlay Therapy: A Non-directive Approach for Children and AdolescentsEdinburgh, UKElsevier Health Sciences2005

- RuzekJIBrymerMJJacobsAKLayneCMVernbergEMWatsonPJPsychological first aidJ Ment Health Counsel20072911749

- VernbergEMSteinbergAMJacobsAKInnovations in disaster mental health: psychological first aidProf Psychol Res Pract2008394381

- HenggelerSWEfficacy studies to large-scale transport: The development and validation of multisystemic therapy programsAnn Rev Clin Psychol2011735138121443449

- SwensonCCSchaefferCMHenggelerSWFaldowskiRMayhewAMMultisystemic therapy for child abuse and neglect: a randomized effectiveness trialJ Fam Psychol201024449720731496