Abstract

Purpose

To determine the incidence of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain (DPNP) in the United Kingdom (UK) primary care population using the General Practice Research Database (GPRD).

Patients and methods

This retrospective cohort study identified incident cases of DPNP in the UK GPRD between July 1, 2002 and June 30, 2011, using diagnostic codes. Trends in the incidence rate were examined by dividing the study period into 3-year periods: (1) July 1, 2002–June 30, 2005; (2) July 1, 2005–June 30, 2008; and (3) July 1, 2008–June 30, 2011. Patient characteristics (age, sex, comorbidities) and initial pharmacological treatment were described; the proportion of patients with incident DPNP, who had previously been screened for neuropathic symptoms, was determined.

Results

Among almost 7.5 million persons contributing 38,118,838 person-years of observations in the GPRD, 6,779 new cases of DPNP were identified (45.5%, women), giving an incidence rate of 17.8 per 100,000 person-years (95% confidence interval [CI] 17.4–18.2). The incidence of DPNP increased with age, but it was stable over the three consecutive 3-year periods: 17.9, 17.2, and 18.4 cases per 100,000 person-years. Of the 6,779 patients with incident DPNP, 15.5% had prior neuropathic screening during the study period. The majority of patients with incident DPNP (84.5%) had a treatment for pain initiated within 28 days of first diagnosis. The most common first-line treatments prescribed were tricyclic antidepressants (27.2%), anticonvulsants (17.0%), and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (14.9%), with 26.6% of patients receiving combination therapy as their initial treatment.

Conclusion

The incidence of DPNP in UK primary care has remained steady over the past 10 years. Our results suggest that DPNP is underdiagnosed, and initial treatment prescribed does not follow clinical guidelines.

Introduction

Peripheral neuropathy affects up to 50% of patients with diabetes and is characterized by pain, paresthesia, and sensory loss, increasing the risk for foot problems that can result in amputation.Citation1 Diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain (DPNP) is generally diagnosed and managed in the primary care setting in the United Kingdom (UK), but it can be difficult for general practitioners (GPs) to recognize, because patients often do not relate pain to diabetes and, therefore, do not volunteer information on their pain symptoms during consultations.Citation2 DPNP is associated with impaired patient functioning and quality of life, as well as higher societal and health care costs compared to patients with diabetes but without neuropathic pain.Citation3,Citation4

Prevalence rates of DPNP in Europe range from 8%–26% in different diabetes patient populations.Citation5–Citation11 In the UK, the prevalence of DPNP in the diabetes population ranges from 10%–26%, depending on the criteria used to assess/define DPNP and the patient population studied.Citation5–Citation7

Incidence of DPNP has been less well-studied, but it is an important measure within the general population to inform health policy for screening and detection and to plan health care resources. A study, using the UK General Practice Research Database (GPRD), estimated the incidence of DPNP at 15.3 cases per 100,000 person-years in the UK primary care population between 1992 and 2002,Citation12 increasing to 27.2 cases per 100,000 person-years between 2002 and 2005.Citation13

In the UK, clinical practice guidelines for patients with diabetes include annual checks for neuropathic symptoms and appropriate pain management plans to improve patient outcomes.Citation2,Citation14 Annual screening of all diabetes patients for neuropathy and a foot examination (including assessment of peripheral pulses and sensation) is part of the Quality Outcome Framework (QOF), a financial incentive scheme for GP practices introduced in 2004.Citation15

Up-to-date DPNP incidence rates will inform health care providers and practitioners on the impact of clinical guidelines and neuropathic screening on the diagnosis and treatment patterns of DPNP in UK primary care; such information is captured in the GPRD.

The objectives of our study were to use the GPRD to determine the impact of the introduction of national guidelinesCitation14 on the incidence of DPNP in the UK primary care population in the last 9 years and to examine trends in the incidence rate over the study period (2002–2011). In addition, we describe the characteristics of the primary care patients with incident DPNP and their initial pharmacological treatment, and we determined the proportion of patients with incident DPNP who had previously been screened for neuropathic symptoms.

Material and methods

Data source

This study used a retrospective cohort design to identify incident cases of DPNP in the UK GPRD between July 1, 2002–June 30, 2011. GPRD records for >5 million currently registered patients meet the GPRD standards of acceptable quality for use in research, which is equivalent to approximately 8.5% of the UK population.Citation16 Recent systematic reviews have confirmed the validity of medical diagnoses and quality of information on the GPRD.Citation17,Citation18

Study population and study cohort with incident DPNP

The total study population included all patients who were permanently registered at one of the GP practices contributing to the GPRD system at any time during the 9-year study period (July 1, 2002–June 30, 2011) and who provided acceptable-quality data as recorded in the GPRD. For each patient, the period of observation was from a start date to an end date. The start date was defined as the last of either: (1) the start of the study period (July 1, 2002); (2) the patient’s date of registration with the practice; or (3) the date the practice was considered “up to standard” by the GPRD. The end date was defined as the first of the following: (1) end of the study period (June 30, 2011); (2) death; (3) transfer out of the practice; or (4) the final data collection.

The study cohort with incident DPNP was identified from the total population and included those who had a GPRD record containing one of the following: a diagnosis of DPNP; a diagnosis of diabetic neuropathy with a prescription for treatment for pain current at the date of diagnosis; a diagnosis of diabetes and neuropathic pain; and a diagnosis of both diabetes and neuralgia plus a treatment for pain current on the data of the neuralgia code. Prescription for treatment for pain includes antidepressants, anticonvulsants, narcotics, nonnarcotics, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). All diagnoses were identified based on Read codes (Table S1 and Table S2). Patients were excluded from the study cohort if they had a DPNP diagnosis in their record prior to the incident date, which was defined as the date of the first DPNP diagnosis recorded in the GPRD during the study period. They were also excluded if they had fewer than 12 months of computerized data prior to the incident date or data not considered of acceptable quality by the GPRD.

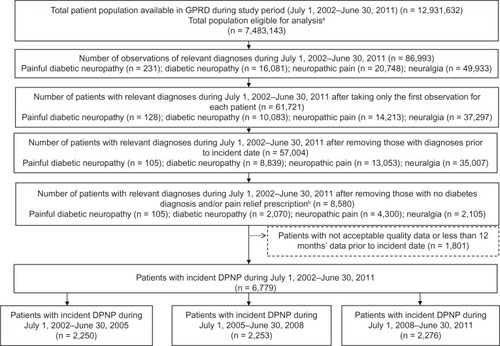

presents the flow chart for identification and selection of the study cohort with incident DPNP in the GPRD.

Figure 1 Flow diagram of selection of patient cohort from GPRD.

Abbreviations: GPRD, General Practice Research Database; DPNP, diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain; n, number.

Data collected

Data on patient age and sex were collected from the GPRD for the total eligible population (n = 7,483,143) and for the study cohort with incident DPNP (n = 6,779).

For the study cohort, information was collected on the most common diabetes-related comorbidities (cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular and peripheral vascular disease, retinopathy, hypoglycemic event, other metabolic diseases, skin problems, nephropathy, obesity, and anxiety) and pain-related comorbidities (lower back pain, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia syndrome, migraine, psoriatic arthropathy, and rheumatoid arthritis). Items from the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) were identified using 17 previously defined categories of comorbid conditions based on Read codes.Citation19 The frequency and percentage of these comorbidities in the 12 months before the incident date were estimated; and the CCI score, a summary measure of index that represents the 1-year mortality for patients based on their history of a range of comorbid conditions, was calculated for each patient.

Information on initial treatment for DPNP was collected within 28 days of the first record of the DPNP diagnosis (incident date) during the study period for: tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs); selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs); serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs); other antidepressants; anticonvulsants; opioids; nonnarcotics; and NSAIDs. The frequency and percentage of each type of drug were estimated. If more than one pharmacotherapy was prescribed on the same day, the initial treatment was considered to be a combination of these therapies.

The frequency and percentage of patients who underwent screening for neuropathic symptoms during the study period were determined by examining Read codes for diabetic peripheral neuropathy screening and diabetic foot examination/screen (Table S3). The number/percentage of patients diagnosed with DPNP after neuropathic screening during the study period was calculated.

Analysis

To replicate the methodology of Hall et al,Citation12 the incidence rate of DPNP per 100,000 person-years of observation was calculated for the total study period and for the three 3-year subperiods: (1) July 1, 2002–June 30, 2005; (2) July 1, 2005–June 30, 2008; and (3) July 1, 2008–June 30, 2011. The incidence of DPNP was also estimated by sex and age groups (0–14, 15–29, 30–44, 45–59, 60–74, 75+ years). The age group for each patient was determined using a reference year, which was either the start of the study period (2002 for the total study period as well as the first subperiod; 2005 for subperiod 2; and 2008 for subperiod 3), or the date of entry into the GPRD if this occurred later than the start of the study period. Confidence intervals (95% CI) for incidence rates were calculated based on Poisson exact CI. The incidence rates of DPNP for the three subperiods were compared using a Poisson regression model for each age group. The number of DPNP cases was the dependent variable, and the period indicator was included as an independent variable. Total years of observations were included as time of exposure. Results of patient characteristics, comorbidities, and medication are based on nonmissing data. All data analyses were carried out using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The total study population eligible for analysis was almost 7.5 million patients (), providing approximately 38.1 million (38,118,838) person-years of observation. Of this total population, 50.9% were female, and the mean age was 35.3 years (standard deviation 23.5).

From the total study population, 6,779 patients were identified as having incident DPNP during the study period (), and summarizes the characteristics of this patient cohort.

Table 1 Characteristics of patient cohort with incident DPNP

The overall incidence of newly diagnosed DPNP during the whole study period was 17.8 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI = 17.4–18.2). shows that the incidence of DPNP increased with age among both men and women, but it did not change significantly over the three subperiods, except among women aged 60–74 years, where the incidence decreased in the period 2008–2011 compared with the two earlier periods (P = 0.001).

Table 2 Incidence of DPNP per 100,000 person-years (95% CI) by sex, age group, and time period

During the whole study period, 90,162 patients in the total study population underwent neuropathic screening. Of these patients, 3,152 (3.5%) had a diagnosis of DPNP after neuropathic screening (but were not necessarily an incident case); and 1,053 (1.2%) were identified with incident DPNP. Of the 6,779 patients in the study cohort with incident DPNP, 1,053 (15.5%) had prior neuropathic screening during the study period (n = 109 for subperiod 1, n = 388 for subperiod 2, and n = 556 for subperiod 3).

A treatment for DPNP was initiated for 5,767 (85.1%) of the patients with incident DPNP within 28 days of diagnosis, and summarizes the initial pharmacological treatment prescribed for these patients. Over the total study period, the most common single first-line treatments were TCAs (27.2%), anticonvulsants (17.0%), and NSAIDs (14.9%), with combination therapy being prescribed as the initial treatment for 26.6% of patients. There was little change in first-line medication use across the three subperiods, except for a slight decrease in the use of opioids and NSAIDs, and a very small increase in the use of SNRIs (). The most common combinations prescribed within 28 days of first diagnosis during the total study period were NSAIDs plus opioids (10.3%); TCAs, plus NSAIDs (9.6%); and TCAs plus opioids (8.6%).

Table 3 Initial treatment prescribed for incident DPNP by type of medication and study period

Discussion

In this study, the overall incidence rate of DPNP in the UK primary care population using the GPRD was 17.8 cases per 100,000 person-years over the 9-year study period from 2002–2011. This is consistent with the previously reported DPNP incident rate of 15.3 cases per 100,000 person-years for 1992–2002,Citation12 where the number of incident cases (per 100,000 person-years) increased over time from 12.9 for 1992–1994, to 14.4 for 1995–1997, to 19.0 for 1998–2001, to 27.2 for 2002–2005. In contrast to the previous studies by Hall et al,Citation12,Citation13 we found little change over time in the incidence of DPNP; the number of incident cases per 100,000 person-years was stable over the three consecutive 3-year periods (17.9, 17.2, and 18.4, respectively).

The total incident cases of DPNP (n = 6,779) during 2002–2011 out of 7.5 million primary care patients can be translated into a crude prevalence rate of 0.5% in the general population, based on the assumption that prevalence is approximately the product of disease incidence and average disease duration, using an assumed duration of DPNP of 5 years.Citation20 Although there is little information on the natural history of DPNP, it is generally believed that painful symptoms resolve or become less prominent over time while the neuropathy continues to progress.Citation21,Citation22 As of 2011, a total of 2.9 million people in the UK have been diagnosed with diabetes, giving an average diabetes prevalence rate of 4.5%.Citation23 Using this diabetes prevalence rate – and assuming that DPNP occurs in 21.0% of people with diabetes based on recent data from >15,000 UK patients with diabetesCitation5 – would provide a DPNP prevalence rate of 0.9% in the general population. While the estimates from our study do not provide a definitive indication of DPNP prevalence rates in the UK, they suggest that DPNP is being underdiagnosed in UK primary care. The results of our study also indicate that general practitioners (GPs) are not prescribing first-line treatments for neuropathic pain as recommended by clinical guidelines,Citation14,Citation24 suggesting that other factors are being taken into consideration when selecting treatment for DPNP.

In clinical practice, DPNP is diagnosed based on clinical signs and symptoms, such as the type of pain, time of pain occurrence, and abnormal sensations; therefore, an accurate diagnosis relies on the patient’s description of pain.Citation22,Citation25 However, patients often do not link pain to diabetes or find it difficult to describe the symptoms they are experiencing and, therefore, may not report their pain symptoms to the doctor.Citation2,Citation6,Citation22 This could be one reason for the underdiagnosis of DPNP in primary care, and highlights the need for physicians to gather information on pain by prompting patients for relevant information, potentially using a simple screening form.Citation26 The annual foot examination and/or test for neuropathy in patients with diabetes is an ideal opportunity to diagnose DPNP, and is part of the QOF scheme for GP practices in the UK, which provides a financial incentive to complete these assessments.Citation6 However, the annual foot screen does not include specific screening questions on pain; there is no financial incentive for providing any diagnosis (including that of DPNP) arising from the assessment. Unexpectedly, we found that only 15.5% of patients with incident DPNP had a previous diabetic peripheral neuropathy screen or foot examination recorded in GPRD. This raises questions about how accurately screening is recorded in GPRD and whether it fully captures the QOF annual screening program, although a recent survey conducted by Diabetes UK found that a quarter of patients with diabetes could not recall having had an annual foot screen.Citation27 Our finding that more than one-half of the incident DPNP cases with prior neuropathic screening occurred in the last subperiod (2008–2011) suggests that diagnosis of DPNP may be improving and that the QOF scheme (introduced in 2004) may be helping. However, as screening was checked for during the total study period (2002–2011), patients identified with DPNP in subperiod 3 had a longer time for screening to be recorded than the patients in subperiod 1. Nevertheless, rates of screening are low and further research over the next few years should make this clearer.

There was a low frequency (<10%) of diabetes- and pain-related comorbidities in the 12 months before DPNP diagnosis, and the most common comorbidities were consistent with those reported previously in a retrospective database study of >11,000 patients with DPNP.Citation28 Some diabetes-related comorbidities (neuropathy, obesity, low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and high levels of triglycerides) have been identified as independent risk factors for DPNP.Citation9

In our study, the majority (85.1%) of patients with incident DPNP started pain-relief medication within 28 days. The most commonly used first-line medications were TCAs, anticonvulsants, and NSAIDs – despite a lack of evidence for NSAID efficacy in DPNP. SNRIs, such as duloxetine, were rarely prescribed as initial treatment. These findings are consistent with other studies in patients with DPNP.Citation3,Citation9,Citation12,Citation20 Interestingly, treatment patterns at the time of first diagnosis of DPNP do not seem to have changed over the 9-year study period and, even in the last 3-year period (2008–2011), only 4.0% of patients received an SNRI as their initial medication. This indicates that patients are not being treated according to current clinical guidelines, which recommend duloxetine as first-line treatment for people with painful diabetic neuropathy, or amitriptyline, if duloxetine is contraindicated.Citation14 It is possible that patients are being prescribed TCAs (alone, or in combination with NSAIDs or opioids) because GPs are unsure of the diagnosis, and these antidepressants are known to be cheap and effective for the treatment of many painful conditions.

This study has several limitations. First, patients with incident DPNP were identified in the GPRD using multiple diagnostic codes covering diabetes, neuropathy, and neuropathic pain, together with prescription of pain relief medication. Although this was relatively straightforward and consistent with a previous publication,Citation12 more accurate data collection would be achieved if there was a consistent and clear definition of DPNP, and a diagnostic code that is uniformly used to record its presence. Second, because of the inclusion criteria, patients with diabetic neuropathy or diabetes plus neuralgia and taking medication for depression or another painful condition may be included, resulting in an overestimation of the incidence of DPNP. Third, our study cohort of patients with incident DPNP does not include patients with impaired glucose tolerance (prediabetes) that may have peripheral neuropathy and/or neuropathic pain.Citation29 Fourth, we were not able to assess pain severity in the GPRD, which may influence the diagnosis of DPNP and prescription of pain medication. Many patients with DPNP report having severe pain,Citation7 and those with severe pain are more likely to receive pain treatment.Citation10 Increasing pain severity is also associated with poorer patient outcomes and increased health care resource use and related costs.Citation30

The strengths of our study include the large sample of primary care patients from the GPRD, which is representative of the UK population and utilizes real-life data that is routinely collected and recorded during primary care consultations. Importantly, as DPNP is typically diagnosed and managed in primary care, GPRD is the most appropriate data source available in the UK. Other strengths of this study are that we used similar methodology to Hall et al,Citation12 and the incidence of DPNP during the 9-year study period was well-defined.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study provides up-to-date information on the incidence rate of DPNP in the UK primary care population. The incidence of DPNP increases with age and more commonly affects men, but it has remained relatively stable over the past 9 years. However, our results suggest that DPNP is underdiagnosed in UK primary care and that treatment on diagnosis does not follow clinical guidelines, indicating the need for improved awareness and education about DPNP. If GPs can provide an early and confident diagnosis of DPNP, they may be more likely to implement treatments that reflect current clinical guideline recommendations, thereby improving patient care and reducing the burden of this disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Deirdre Elmhirst for medical writing assistance, which was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Supplementary tables

Table S1 Read codes for diabetes

Table S2 Read codes for DPNP

Table S3 Read codes for DPNP screening

Disclosure

This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company Limited. Catherine Reed, Diego Novick, Alan Lenox-Smith, and Michael Happich are employees of Eli Lilly and Company Limited. Jihyung Hong is a consultant for Eli Lilly and Company Limited. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- TesfayeSSelvarajahDAdvances in the epidemiology, pathogenesis and management of diabetic peripheral neuropathyDiabetes Metab Res Rev201228Suppl 181422271716

- National Collaborating Centre for Chronic ConditionsType 2 Diabetes: National Clinical Guideline for Management in Primary and Secondary Care (Update)London, UKRoyal College of Physicians2008

- GoreMBrandenburgNAHoffmanDLTaiKSStaceyBBurden of illness in painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: the patients’ perspectivesJ Pain200671289290017157775

- daCosta DiBonaventuraMCappelleriJCJoshiAVA longitudinal assessment of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy on health status, productivity, and health care utilization and costPain Med201112111812621087406

- AbbottCAMalikRAvan RossERKulkarniJBoultonAJPrevalence and characteristics of painful diabetic neuropathy in a large community-based diabetic population in the UKDiabetes Care201134102220222421852677

- DaousiCMacFarlaneIAWoodwardANurmikkoTJBundredPEBenbowSJChronic painful peripheral neuropathy in an urban community: a controlled comparison of people with and without diabetesDiabet Med200421997698215317601

- DaviesMBrophySWilliamsRTaylorAThe prevalence, severity, and impact of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetesDiabetes Care20062971518152216801572

- PartanenJNiskanenLLehtinenJMervaalaESiitonenOUssitupaMNatural history of peripheral neuropathy in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitusN Engl J Med1995333289947777034

- Van AckerKBouhassiraDDe BacquerDPrevalence and impact on quality of life of peripheral neuropathy with or without neuropathic pain in type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients attending hospital outpatients clinicsDiabetes Metab200935320621319297223

- WuEQBortonJSaidGEstimated prevalence of peripheral neuropathy and associated pain in adults with diabetes in FranceCurr Med Res Opin20072392035204217637204

- ZieglerDRathmannWDickhausTMeisingerCMielckAKORA Study GroupNeuropathic pain in diabetes, prediabetes and normal glucose tolerance: the MONICA/KORA Augsburg Surveys S2 and S3Pain Med200910239340019207236

- HallGCCarrollDParryDMcQuayHJEpidemiology and treatment of neuropathic pain: the UK primary care perspectivePain20061221–215616216545908

- HallGCCarrollDMcQuayHJPrimary care incidence and treatment of four neuropathic pain conditions: a descriptive study, 2002–2005BMC Fam Pract200892618460194

- Centre for Clinical Practice at NICE (UK)Neuropathic Pain: The Pharmacological Management of Neuropathic Pain in Adults in Non-Specialist SettingsLondon, UKNational Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence2010

- Quality and Outcomes Framework for 2012/13 Available at: http://www.nhsemployers.org/Aboutus/Publications/Documents/QOF_2012-13.pdfAccessed June 25, 2012

- General Practice Research Database Available at: http://www.gprd.comAccessed March 21, 2012

- HerrettEThomasSLSchoonenWMSmeethLHallAJValidation and validity of diagnoses in the General Practice Research Database: a systematic reviewBr J Clin Pharmacol201069141420078607

- KhanNFHarrisonSERosePWValidity of diagnostic coding within the General Practice Research Database: a systematic reviewBr J Gen Pract201060572e128e13520202356

- KhanNFPereraRHarperSRosePWAdaptation and validation of the Charlson Index for Read/OXMIS coded databasesBMC Fam Pract201011120051110

- DaousiCBenbowSJWoodwardAMacFarlaneIAThe natural history of chronic painful peripheral neuropathy in a community diabetes populationDiabet Med20062391021102416922710

- VevesABackonjaMMalikRAPainful diabetic neuropathy: epidemiology, natural history, early diagnosis, and treatment optionsPain Med20089666067418828198

- TesfayeSVileikyteLRaymanGon behalf of the Toronto Expert Panel on Diabetic NeuropathyPainful Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: Consensus Recommendations on Diagnosis, Assessment and ManagementDiabetes Metab Res Rev Epub6212011

- Diabetes prevalence 2011102011 Available at: http://www.diabetes.org.uk/Professionals-old/Publications-reports-and-resources/Reports-statistics-and-case-studies/Reports/Diabetes-prevalence-2011-Oct-20111/Accessed December 4, 2012

- AttalNCruccuGBaronREuropean Federation of Neurological SocietiesEFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revisionEur J Neurol20101791113e8820402746

- TesfayeSBoultonAJDyckPJDiabetic neuropathies: update on definitions, diagnostic criteria, estimation of severity, and treatmentsDiabetes Care2010332285229320876709

- MalikRBakerNBartlettKAddressing the burden of DPNP: improving detection in primary careSponsored supplement to The Diabetic Foot Journal2010134 Diabetes and Primary Care2011131

- MayorSA quarter of diabetic patients miss out on annual foot checks, UK survey warnsBMJ2011343d740522089750

- ChenSWuNBoulangerLFraserKZhaoZZhaoYFactors associated with pain medication selection among patients diagnosed with diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain: a retrospective studyJ Med Econ201114441142021615268

- ZieglerDPainful diabetic neuropathy: advantage of novel drugs over old drugs?Diabetes Care200932Suppl 2S414S41919875591

- DiBonaventuraMCCappelleriJCJoshiAVAssociation between pain severity and health care resource use, health status, productivity and related costs in painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy patientsPain Med201112579980721481171