Abstract

Objective

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is characterized by phenotypic heterogeneity and has a wide variety of consequences. Approximately half of women with PCOS are overweight or obese, and their obesity may be a contributing factor to PCOS pathogenesis through different mechanisms. The aim of this study was to evaluate if PCOS alone affects the patients’ quality of life and to what extent obesity contributes to worsen this disease.

Design

To evaluate the impact of PCOS on health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL), 100 Mediterranean women with PCOS (group A), 50 with a body mass index (BMI) >25 kg/m2 (group A1) and 50 with BMI <25 kg/m2 (group A2), were recruited. They were evaluated with a specific combination of standardized psychometric questionnaires: the Symptom Checklist-90 Revised, the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey, and the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Questionnaire. The patients were compared with a normal-weight healthy control group of 40 subjects (group B). Another control group of 40 obese healthy women (group C) was used to make a comparison with PCOS obese patients (A1).

Results

Our results showed a considerable worsening of HRQoL in PCOS patients (A) compared with controls (B). In addition, patients with PCOS and BMI >25 (A1) showed a significant and more marked reduction in scores, suggesting a lower quality of life, compared with controls (B) and with normal-weight PCOS patients (A2).

Conclusion

PCOS is a complex disease that alone determines a deterioration of HRQoL. The innovative use of these psychometric questionnaires in this study, in particular the PCOS questionnaire, has highlighted that obesity has a negative effect on HRQoL. It follows that a weight decrease is associated to phenotypic spectrum improvement and relative decrement in psychological distress.

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common, endocrine-metabolic disorder affecting premenopausal women and has a prevalence ranging from 5% to 10% among Mediterranean women,Citation1 but its pathophysiology has not yet been fully understood.Citation2 PCOS is characterized by oligo-anovulatory menstrual cycles, larger and micropoly-cystic ovaries, and a variable degree of hyperandrogenism,Citation3 and it is usually associated with metabolic disorders (insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, obesity, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus type 2, etc) and higher cardiovascular risk.Citation4,Citation5

Approximately half of women with PCOS are overweight or obese.Citation6–Citation15 The pathogenetic role of obesity can affect different mechanisms, of which the most important is the hyperinsulinemic state given that insulin can stimulate ovary androgen secretion and play an important role in the metabolism of androgens and their transport to peripheral tissues.Citation16,Citation17 Abdominal fat distribution in obese PCOS women can increase the degree of hyperandrogenism and its related clinical symptoms and signs.Citation18,Citation19 Though the role of obesity is generally acknowledged, relatively little attention has been focused on its real impact on the patients’ quality of life.Citation20 This condition can weigh heavily against the carrying out of daily work and social activities, thus causing a significant reduction in health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) in young patients.Citation21–Citation23 HRQoL represents a multidimensional index of physical, psychological, and social aspects associated with a specific pathology. The aim of this study was to evaluate how PCOS alone affects the quality of life and to assess to what extent obesity negatively influences it. In other words, this study evaluated the impact that the specific association between PCOS and obesity has on HRQoL.

Materials and methods

All recruited patients met the Rotterdam criteria of European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, Ameri-can Society for Reproductive Medicine-sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group (2003).Citation24 Participants were provided with both written and oral information regarding the study protocol and were informed that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time. All subjects gave their written informed consent before participation. All procedures conformed to the directives of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study has been approved by the Azienda Universitaria Policlinico of the Second University of Naples. We recruited 100 Mediterranean women with PCOS aged 17.2–29 years divided into the following groups: (mean age: 23.1±5.9 years) (group A) 50 with a body mass index (BMI) >25 kg/m2 (group A1; aged 22.8±5.6 years; BMI: 31.6±5.8 kg/m2) and 50 with a BMI <25 kg/m2 (group A2; aged 23.3±6.1 years; BMI: 22.3±1.6 kg/m2). The patients were compared with a healthy normal-weight control group of 40 patients ranging from 16.4 to 31.8 years, who were age-matched and had a similar socioeconomic background (group B; aged 24.1±7.7 years; BMI: 22.0±2.1 kg/m2). Another control group of 40 obese healthy women aged from 17.1 to 29.5 years (group C; aged 23.3±6.2 years; BMI: 28.4±2.2 kg/m2) was used to make a comparison with PCOS obese patients (A1) to establish to what extent the worsening of quality of life can be ascribed to PCOS alone and to what, instead, it can be ascribed to an elevated BMI. These patients were administered the following questionnaires with the aim of evaluating the impact of the clinical spectrum of PCOS on HRQoL:Citation25

Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (SCL-90-R)

It includes 90 items grouped into 10 main domains: Somatization (SOM), Obsessive–Compulsive (O–C), Interpersonal Sensitivity (INT), Depression (DEP), Anxiety (ANX), Aggression (HOS), Phobia (PHOB), Paranoid Ideation (PAR), Psychoticism (PSY), and Sleep Disorders (SLEEP). To each question of a single domain can be attributed a score from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). Higher scores are indicative of worse conditions.

36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF 36)

It is a generic questionnaire used to evaluate HRQoL, the activity level, and the feeling of individual well-being. It consists of 36 items organized into eight domains: Physical Function (AF), Physical Role Function (RF), Bodily Pain (BP), General Health (GH), Vitality (VT), Social Function (SF), Emotional Role Function (RE), and Mental Health (SM) as well as an item on the change of General Health. The scores of each domain have been converted into a scale from 0 to 100. Lower scores are indicative of worse conditions.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Questionnaire (PCOSQ)

A specific questionnaire used to outline the impact of the symptoms and signs of PCOS on HRQoL and whose proprieties were previously validated.Citation26 PCOSQ contains 26 items organized into five domains: Emotions (EMOT), Hirsutism (HIRS), Body Weight (BW), Infertility (INF), and Menstrual Disorders (MD). In addition, for the present study, an “acne” domain with four different items useful to reinforce the usefulness of PCOSQ was also included.Citation27 A score from 1 (always) to 7 (never) has been attributed to each question. Lower scores are indicative of more serious conditions. An arbitrary threshold of three was fixed, and the patient was considered “seriously” affected in the domains in which they scored above 3.

Pearson’s coefficient was used to interpret the correlation between BMI and each of the test domains. The Student’s t-test was used to verify the significance of the differences in the main score for each domain between PCOS and healthy group (A vs B), PCOS obese and PCOS lean patients (A1 vs A2), and, finally, PCOS obese patients and healthy obese controls (A1 vs C). The level of significance was fixed, in all the cases, at 0.05.

Results

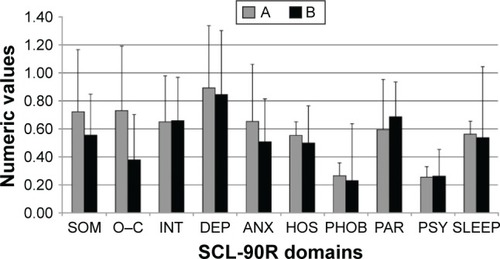

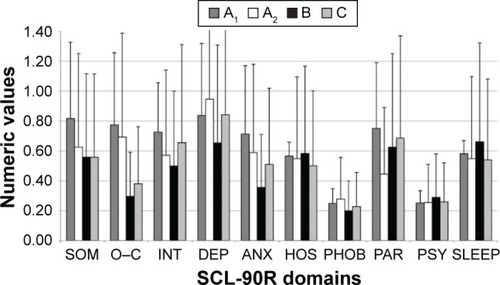

SCL-90-R revealed significantly elevated scores in PCOS patients (A) compared with controls (B) in three symptomatic dimensions: O–C (A: 0.7±0.5; B: 0.3±0.3; P<0.001), DEP (A: 0.9±0.4; B: 0.7±0.5; P=0.03), and ANX (A: 0.7±0.4; B: 0.4±0.3; P=0.003) (). In addition, there was a positive correlation between BMI and 1) SOM (P<0.001), confirmed also by Student’s t-test (A1: 0.8±0.5; A2: 0.6±0.3; P=0.03); 2) INT (P<0.001), confirmed also by Student’s t-test (A1: 0.7±0.3; A2: 0.6±0.3; P=0.02); and 3) PAR (P<0.001), confirmed also by Student’s t-test (A1: 0.8±0.4; A2: 0.5±0.1; P<0.001) (). Finally, the comparison between healthy obese women (C) and PCOS obese patients (A1) revealed higher scores in the latter in the following domains: SOM (A1: 0.8±0.5; C: 0.6±0.3; P<0.05), O–C (A1: 0.8±0.5; C: 0.4±0,1; P<0.001), ANX (A1: 0.7±0.5; C: 0.5±0.1; P=0.005), HOS (A1: 0.6±0.1; C: 0.5±0.1; P<0.001), PHOB (A1: 0.3±0.1; C: 0.2±0.2; P=0.05), and INT (A1: 0.6±0.1; C: 0.5±0.2; P<0.001).

Figure 1 SCL-90-R in PCOS patients (A) and healthy normal-weight controls (B).

Abbreviations: PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; SCL-90-R, Symptom Checklist 90-Revised; SOM, somatization; O–C, obsessive–compulsive; INT, interpersonal sensitivity; DEP, depression; ANX, anxiety; HOS, aggression; PHOB, phobia; PAR, paranoid ideation; PSY, psychoticism; SLEEP, sleep disorders.

Figure 2 SCL-90-R in PCOS obese patients (A1), PCOS normal-weight patients (A2), normal-weight healthy controls (B), and healthy obese controls (C).

Abbreviations: PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; SCL-90-R, Symptom Checklist 90-Revised; SOM, somatization; O–C, obsessive–compulsive; INT, interpersonal sensitivity; DEP, depression; ANX, anxiety; HOS, aggression; PHOB, phobia; PAR, paranoid ideation; PSY, psychoticism; SLEEP, sleep disorders.

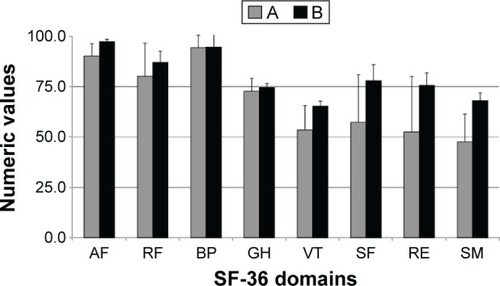

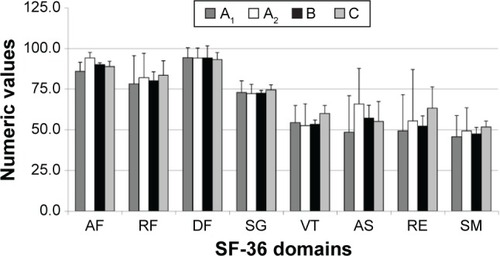

With regard to SF36, it was shown that PCOS patients (A), compared with healthy controls (B), had decreased scores, indicating lower quality of life, in the domains of VT (A: 53.4±12.1; B: 65.2±2.5; P<0.001), RE (A: 52.3±27.6; B: 75.6±6.1; P<0.001), SM (A: 47.5±13.7; B: 68.0±3.9; P<0.001), SF (A: 57.1±23.8; B: 77.8±8.0; P<0.001), and AF (A: 90.1±6.2; B: 97.3±1.2; P<0.001). No significant difference was found in the domains of RF (A: 80.1±16.3; B: 86.9±5.5; P=0.07), GH (A: 72.6±6.5; B: 74.9±1.6; P=0.11), and BP (A: 94.1±6.2; B: 95.0±7.4; P=0.802) (). In addition, there was a positive correlation between BMI and 1) AP (P<0.001), confirmed also by Student’s t-test (A1: 85.9±5.5; A2: 94.2±3.4; P<0.001) and 2) SF (P<0.001), confirmed also by Student’s t-test (A1: 48.5±22.4; A2: 65.8±21.9; P<0.001) (). Finally, the comparison between healthy obese women (C) and PCOS obese patients (A1) revealed higher scores in the latter group in the following domains: AF (A1: 85.9±5.5; C: 88.8±3.3; P<0.001), VT (A1: 54.3±10.6; C: 60.0±5.0; P=0.001), RE (A1: 49.3±22.4; C: 63.2±13.1; P<0.0001), and SM (A1: 45.7±12.9; C: 51.7±3.6; P=0.005).

Figure 3 SF-36 in PCOS patients (A) and healthy normal-weight controls (B).

Abbreviations: PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; SF-36, 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey; AF, physical function; RF, physical role function; BP, bodily pain; GH, general health; VT, vitality; SF, social function; RE, emotional role function; SM, mental health.

Figure 4 SF-36 in PCOS obese patients (A1), PCOS normal-weight patients (A2), lean normal-weight healthy controls (B), and healthy obese controls (C).

Abbreviations: PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; SF-36, 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey; AF, physical function; RF, physical role function; VT, vitality; RE, emotional role function; SM, mental health; DF, emotional well-being; SG, social functioning; AS, health change.

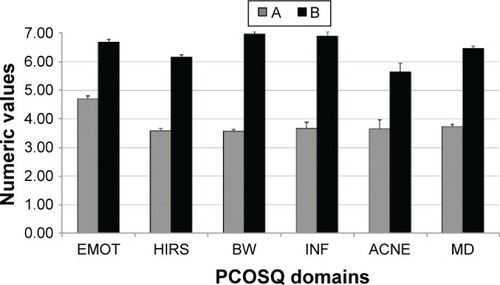

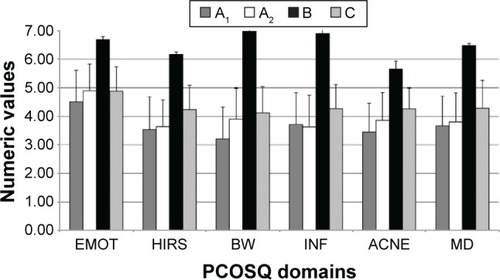

PCOS patients (A), compared with controls (B), had significantly lower scores in PCOSQ in the domains of: EMOT (A: 4.7±1.1; B: 6.7±0.1; P<0.001), HIRS (A: 3.6±1.0; B: 6.2±0.1; P<0.001), BW (A: 3.6±1.2; B: 7.0±0.1; P<0.001), INF (A: 3.7±1.1; B: 6.9±0.2; P<0.001), ACNE (A: 3.7±1.0; B: 5.6±0.3; P<0.001), and MD (A: 3.7±1.0; B: 6.5±0.1; P<0.001) (). In addition, there was a positive correlation between BMI and 1) EMOT (P<0.001), confirmed also by Student’s t-test (A1: 4.5±1.1; A2: 4.9±0.9; P<0.001); 2) BW (P<0.001), confirmed also by Student’s t-test (A1: 3.2±1.1; A2: 3.9±1.1; P<0.001); and 3) ACNE (P<0.01), confirmed also by Student’s t-test (A1: 3.4±1.0; A2: 3.9±1.0; P=0.03) (). Having set the pathological threshold of the mean score at 3, the most frequently affected domains were BW (22%), Hirs (19%), Emot (18%), Acne (18%), Inf (17%), and MD (17%). Finally, the comparison between healthy obese women (C) and PCOS obese patients (A1) revealed higher scores in the latter group in all the domains of the test: EMOT (A1: 4.5±1.1; C: 4.9±0.9; P<0.05), HIRS (A1: 3.5±1.2; C: 4.2±0.9; P<0.002), BW (A1: 3.2±1.1; C: 4.1±0.9; P<0.0001), INF (A1: 3.7±1.1; C: 4.3±0.8; P=0.003), MD (A1: 3.7±1.0; C: 4.3±1; P=0.001), and ACNE (A1: 3.4±1.0; C: 4.2±0.7; P<0.0001). A positive correlation (P<0.05) was found between BMI and all the domains of SF-36, SCL-90-R, and PCOSQ in the PCOS group (A) and in the control healthy group (B), whereas in the healthy obese group (C) a positive correlation of BMI was revealed only with BP and SM of SF-36, SOM, and PSY of SCL-90-R and none of the PCOSQ domains.

Figure 5 PCOSQ in PCOS patients (A) and healthy normal-weight controls (B).

Abbreviations: PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; PCOSQ, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Questionnaire; EMOT, emotions; HIRS, hirsutism; BW, body weight; INF, infertility; MD, menstrual disorders.

Figure 6 PCOSQ in PCOS obese patients (A1), PCOS normal-weight patients (A2), normal-weight healthy controls (B), and healthy obese controls (C).

Abbreviations: PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; PCOSQ, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Questionnaire; EMOT, emotions; HIRS, hirsutism; BW, body weight; INF, infertility; MD, menstrual disorders.

Discussion

PCOS, characterized by phenotypic heterogeneity and a wide variety of long-term metabolic and cardiovascular complicances,Citation28 is an important cause of severe distress. In fact, hirsutism causes considerable psychological distress confirmed by psychometric evaluation, which reveals marked anxiety and social discomfort;Citation29 infertility causes family tensions and problems at work, while obesity in PCOS women is responsible for a general state of depression and dissatisfaction.Citation30,Citation31 An important study made by Cronin reported that the main problems for the women affected by PCOS were hirsutism (90%), being overweight (84%), menstrual disorders (82%), and difficulties maintaining their body weight (80%).Citation32,Citation33

This study focuses on a Mediterranean population assessed using SCL-90-R, SF-36, and PCOSQ, correlating, for every group, the test scores with BMI. Psychological disturbances, measured by SCL-90-R, strongly influence global well-being. In particular, in PCOS patients (A), the O–C, DEP, and ANX dimensions were considerably affected independently of BMI, as reported in other studies.Citation34,Citation35 Among the main causes of depression and anxiety is probably the dissatisfaction with the body image or womanly identity. Obese patients (A1), moreover, showed significant changes in the dimensions of SOM, INT, and PAR, probably because they showed a more serious phenotypic expression of PCOS and so had difficulty in establishing relations and showed a severe antisocial attitude that could lead to a much greater tendency to somatization. The analysis of SCL-90-R showed that being overweight or obese was not the only determining factor, as demonstrated by the distortion of many domains even in women with normal BMI. HRQoL result worsened also when was evaluated with SF-36. In particular, the domains more significantly affected in the PCOS sample were VT, RE, MH, SF, and AP. This finding suggests that PCOS, regardless of BMI, determines a relevant impairment of psychosocial functions. The domains of SF and AP, however, were significantly more affected in patients with BMI >25 (A1) compared with controls (B). This is in-line with other studies, which also have shown that BMI in the SF-36 is a physical score predictor.Citation36,Citation37 In our study, however, no significant difference was found for the scales of RF, BP, and GH. However, PCOSQ appeared the most sensitive test for the evaluation of HRQoL, and it can provide a lot of information on the causes of psychological distress. PCOSQ identifies weight gain as one of the most important causes of distress in PCOS patients. In particular, PCOS obese patients (A1), compared with nonobese ones (A2), showed a further increase in scores in the domain of BW, ACNE, and EMOT, which emphasizes how the association between PCOS and overweight/obesity can cause a severe worsening of the emotional and the physical domains. The main domains involved were BW (22%) and HIRS (19%), as reported in other studies,Citation38,Citation39 followed by EMOT and ACNE (both 18%), and INF and MD (both 17%). It is important to note that infertility, one of the main malfunctions related to PCOS,Citation40–Citation42 proved to be a minor determinant in this study. The reason for this contrasting finding may be the younger age of our sample – a time when maternity is not considered a priority yet. However, the BMI is not the only determinant of worsening of quality of life in PCOS patients, given that from the comparison between PCOS obese women (A1) and obese controls (C), emerged a significant alteration in a lot of the domains: AF, VT, RE, SM (SF-36), SOM, O-C, ANX, HOS, PHOB, SLEEP (SCL-90-R), and in all of the PCOSQ domains. This evidence suggests that PCOS by itself makes worse the quality of life, whereas obesity, when it is present, configures itself as a pejorative element.

Therefore, given that PCOS is an important cause of psychic distress,Citation43 it would be necessary to carry out a psychological screening by making use of HRQoL measurements,Citation44–Citation46 besides the routine physical, laboratory, and instrumental examinations, in order to evaluate the fragile psychological balance of these women. We believe that PCOSQ is the most sensitive test to evaluate HRQoL in PCOS patients, as highlighted by the evidence that the differences between the groups studied with PCOSQ were more markedly significant than the ones that emerged from the analysis of the scores obtained from other tests.

The general aim of any treatment is to reach a state of “good health”, which, according to World Health Organization, coincides with the concept of psychophysical well-being and implies a healthy perception of our body and a good relation with ourselves.Citation47–Citation50 The restoration of psychophysical well-being is, therefore, the main objective of a proper treatment of PCOS; so this endocrinopathy requires an approach aimed at improving the quality of life and self-perception as well as the symptoms of the disease. Particularly, special care is needed by obese PCOS patients, because their more severe phenotype exposes them to a greater risk of developing serious psychic distress.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results from our study confirmed the negative impact of PCOS on the patients’ quality of life and particularly highlighted how obesity contributes to its phenotypic spectrum, thus becoming an important pejorative element.

Author contributions

Annalisa Panico and Giovanni Messina contribute equally to the article. Giovanni Messina and Antonietta Messina are second-degree relatives. Gelsy Arianna Lupoli, Roberta Lupoli, and Giovanni Lupoli are first-degree relatives. Vincenzo Monda and Marcellino Monda are first-degree relatives. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Disclosure

The authors reports no conflicts of interests in this work.

References

- BarberTMMcCarthyMIWassJAHFranksSObesity and polycystic ovary syndromeClin Endocrinol (Oxf)200665213714516886951

- NormanRJDewaillyDLegroRSHickeyTEPolycystic ovary syndromeLancet (London, England)20073709588685697

- CarminaEAzzizRDiagnosis, phenotype, and prevalence of polycystic ovary syndromeFertil Steril200686Suppl 1S7S816798288

- GuzickDSDo cardiovascular risk factors in polycystic ovarian syndrome result in more cardiovascular events?J Clin Endocrinol Metab20089341170117118390812

- ViggianoAVicidominiCMondaMFast and low-cost analysis of heart rate variability reveals vegetative alterations in noncomplicated diabetic patientsJ Diabetes Complications200923211912318413209

- WitchelSFRoumimperHOberfieldSPolycystic ovary syndrome in adolescentsEndocrinol Metab Clin North Am201645232934427241968

- RosenfieldRLThe diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescentsPediatrics201513661154116526598450

- ChieffiSIachiniTIavaroneAMessinaGViggianoAMondaMFlanker interference effects in a line bisection taskExp Brain Res201423241327113424496492

- VerrottiAAgostinelliSD’EgidioCImpact of a weight loss program on migraine in obese adolescentsEur J Neurol201320239439722642299

- CarotenutoMSantoroNGrandoneAThe insulin gene variable number of tandemrepeats (INS VNTR) genotype and sleep disordered breathing in childhood obesityJ Endocrinol Invest200932975275519574727

- CarotenutoMBruniOSantoroNdel GiudiceEMPerroneLPascottoAWaist circumference predicts the occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing in obese children and adolescents: a questionnaire-based studySleep Med20067435736116713341

- MessinaGMondaVMoscatelliFRole of orexin in obesity system, biology and medicineBiol Med2015741000248

- HungJHHuLYTsaiSJRisk of psychiatric disorders following polycystic ovary syndrome: a nationwide population-based cohort studyPLoS One201495712

- TockLCarneiroGTogeiroSMObstructive sleep apnea predisposes to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with polycystic ovary syndromeEndocr Pract201420324425124246334

- ShreeveNCagampangFSadekKPoor sleep in PCOS; is melatonin the culprit?Hum Reprod20132851348135323438443

- StanleyTMisraMPolycystic ovary syndrome in obese adolescentsCurr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes2008151303618185060

- ViggianoANicodemoUViggianoEMastication overload causes an increase in O2-production into the subnucleus oralis of the spinal trigeminal nucleusNeuroscience2010166241642120045451

- GoodarziMODumesicDAChazenbalkGAzzizRPolycystic ovary syndrome: etiology, pathogenesis and diagnosisNat Rev Endocrinol20117421923121263450

- MessinaGDaliaCTafuriDOrexin-A controls sympathetic activity and eating behaviorFront Psychol2014599725250003

- EspositoMGallaiBRoccellaMAnxiety and depression levels in prepubertal obese children: a case – control studyNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2014101897190225336955

- JonesGLHallJMBalenAHLedgerWLHealth-related quality of life measurement in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic reviewHum Reprod Update2008141152517905857

- MoscatelliFMessinaGValenzanoADifferences in corticospi-nal system activity and reaction response between karate athletes and non-athletesNeurol Sci201637121947195327544220

- ViggianoAChieffiSTafuriDMessinaGMondaMDe LucaBLaterality of a second player position affects lateral deviation of basketball shootingJ Sports Sci2014321465223876006

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop GroupRevised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndromeFertil Steril20048111925 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14711538

- CoffeySBanoGMasonHDHealth-related quality of life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a comparison with the general population using the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Questionnaire (PCOSQ) and the Short Form-36 (SF-36)Gynecol Endocrinol2006222808616603432

- JonesGLBenesKClarkTLThe Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Health-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire (PCOSQ): a validationHum Reprod2004192371377 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1474718414747184

- MoscatelliFValenzanoAPetitoARelationship between blood lactate and cortical excitability between taekwondo athletes and non-athletes after hand-grip exerciseSomatosens Mot Res201633213714427412765

- AzzizRWoodsKSReynaRKeyTJKnochenhauerESYildizBOThe prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected populationJ Clin Endocrinol Metab2004892745274915181052

- MoscatelliFMessinaGValenzanoAFunctional assessment of corticospinal system excitability in karate athletesPLoS One2016115e015599827218465

- PaulsonJDHaarmannBSSalernoRLAsmarPAn investigation of the relationship between emotional maladjustment and infertilityFertil Steril19884922582623338582

- HimeleinMJThatcherSSDepression and body image among women with polycystic ovary syndromeJ Health Psychol200611461362516769740

- CroninLGuyattGGriffithLDevelopment of a health-related quality-of-life questionnaire (PCOSQ) for women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)J Clin Endocrinol Metab1998836197619879626128

- Di BernardoGMessinaGCapassoSSera of overweight people promote in vitro adipocyte differentiation of bone marrow stromal cellsStem Cell Res Ther201451424405848

- ElsenbruchSHahnSKowalskyDQuality of life, psychosocial well-being, and sexual satisfaction in women with polycystic ovary syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab200388125801580714671172

- MondaMMessinaGScognamiglioIShort-term diet and moderate exercise in young overweight men modulate cardiocyte and hepatocarcinoma survival by oxidative stressOxid Med Cell Longev20142014317

- HahnSJanssenOETanSClinical and psychological correlates of quality-of-life in polycystic ovary syndromeEur J Endocrinol2005153685386016322391

- MessinaGDi BernardoGViggianoAExercise increases the level of plasma orexin A in humansJ Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol201627661161627665420

- PekhlivanovBKolarovGKavurdzhikovaSStoikovSDeterminants of health related quality of life in women with polycystic ovary syndromeAkush Ginekol (Sofiia)20064572934

- ChieffiSIavaroneAIaccarinoLAge-related differences in distractor interference on line bisectionExp Brain Res2014232113659366425092273

- TanSHahnSBensonSPsychological implications of infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndromeHum Reprod20082392064207118583330

- McCookJGReameNEThatcherSSHealth-related quality of life issues in women with polycystic ovary syndromeJ Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs20053411220

- MondaMMessinaGMangoniCResting energy expenditure and fat-free mass do not decline during aging in severely obese womenClin Nutr200827465765918514973

- PaschLHeSYHuddlestonHClinician vs self-ratings of hirsutism in patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome: associations with quality of life and depressionJAMA Dermatol2016152778378826942548

- LinCYOuHTWuMHChenPCValidation of Chinese version of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Health-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire (Chi-PCOSQ)PLoS One2016114e015434327124836

- MessinaGDe LucaVViggianoAAutonomic nervous system in the control of energy balance and body weight: personal contributionsNeurol Res Int2013201363928023691314

- MondaMViggianoADe LucaVHaloperidol reduces the sympathetic and thermogenic activation induced by orexin ANeurosci Res2003451172312507720

- MondaMViggianoAViggianoASympathetic and hyperther-mic reactions by orexin A: role of cerebral catecholaminergic neuronsRegul Pept20071391–3394417134769

- ValenzanoAMoscatelliFTriggianiAIHeart-rate changes after an ultraendurance swim from Italy to Albania: a case reportInt J Sports Physiol Perform201611340740926263484

- MessinaGPalmieriFMondaVExercise causes muscle GLUT4 translocation in an insulin-independent mannerBiol Med20151214

- MoscatelliFMessinaGValenzanoARelationship between RPE and blood lactate after fatiguing handgrip exercise in taekwondo and sedentary subjectsBiol Med20151S3008