Abstract

Effective doctor–patient communication is essential for establishing a successful doctor–patient relationship and implementing high-quality health care. In this study, a novel urinary system-simulating physical model was designed and fabricated, and its content validity for improving doctor–patient communication was examined by conducting a randomized controlled trial in which this system was compared with photographs. A total of 240 inpatients were randomly selected and assigned to six doctors for treatment. After primary diagnosis and treatment had been determined, these patients were randomly divided into the experimental group and the control group. Patients in the experimental group participated in model-based doctor–patient communication, whereas control group patients received picture-based communication. Within 30 min after this communication, a Demographic Information Survey Scale and a Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale (MISS) were distributed to investigate patients’ demographic characteristics and their assessments of total satisfaction, distress relief, communication comfort, rapport, and compliance intent. The study results demonstrated that the individual groups were comparable with respect to demographic variables but that relative to patients in the picture-based communication group, patients in the model-based communication group had significantly higher total satisfaction scores and higher ratings for distress relief, communication comfort, rapport, and compliance intent. These results indicate that the physical model is more effective than the pictures at improving doctor–patient communication and patient outcomes. The application of the physical model in doctor–patient communication is helpful and valuable and therefore merits widespread clinical popularization.

Introduction

Doctor–patient communication has been shown to be fundamental in clinical practice, and the main goals of communication have been to create good interpersonal relationships, to facilitate the exchange of information, and to include patients in decision-making.Citation1–Citation4 In contemporary medicine, communication has been gaining increasing attention as more health care providers have recognized that it is essential to health.Citation5 Studies have shown that good doctor–patient communication can enhance the doctor–patient relationship, improve patient satisfaction with medical encounters, and decrease patients’ psychological stress and symptoms and was associated with improved trust in health care providers, increased satisfaction with care, greater patient confidence in and adherence to treatment plans, and improved medical outcomes.Citation6–Citation10 Inversely, poor communication and attitudes between the doctor and patient constitute the most frequent underlying cause of malpractice litigation, complaints against doctors, and nonadherence to medication regimens.Citation11–Citation14 Thus, developing strategies to strengthen communication has become a central topic in clinical and social research. Given this phenomenon, in this study, a novel urinary system-simulating physical model was designed and fabricated, and a randomized controlled trial was performed to test this model’s content validity for improving doctor–patient communication by comparing the model with pictures.

Materials and methods

Model fabrication and pictures preparation

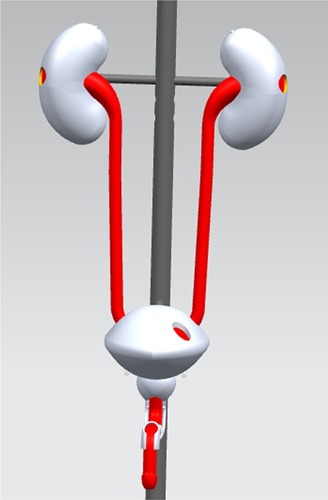

The model, which was based on human anatomical structure, was designed using UG NX software. presents one of the images of the male urinary system created during the design process. All images were retained and printed for use as pictures assessed in the content validity trial. The physical model designed based on these images was then fabricated using MasterCAM software and a CNC machine. The main components included in the model were the kidneys, ureters, bladder, prostate, and urethra: the model was created using transparent acrylic and silicone rubber. shows the male urinary system-simulating physical model. It is transparent and anatomically accurate, and could be used to demonstrate multiple clinical abnormalities and operations, including lithiasis in the urinary system, obstructions, tumors, catheterization, cystoscopy, ureteroscopy, and ureteral stent insertion and removal.Citation15

Content validity examination

Participants and grouping

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the XinQiao Hospital (Second Affiliated Hospital of Third Military Medical University) in China and was conducted in the Urology Department from 2012 to 2013. The design involved a randomized trial with two arms (model-based communication and pictures-based communication). Six urologists, who were selected through stratified sampling by professional qualification (chief physician, associate chief physician, attending physician, resident [1:1:1:3]) from the 12 urologists in the Urology Department of the XinQiao Hospital, participated in the research. Two specific researchers were assigned to take charge of random allocation, conduct the questionnaire investigation, and collect the data. A total of 240 inpatients aged ≥18 years were invited to attend the study and given an informed consent form. Patients who were blind, in a coma, unable to speak Chinese, or suffering from a major mental illness were excluded from the study.

Research procedure

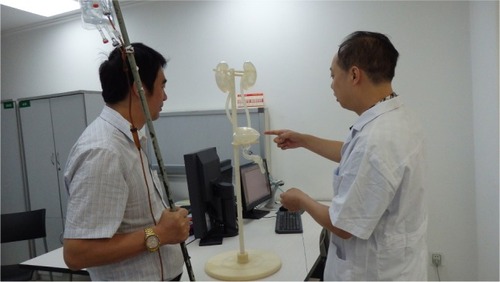

Considering seasonal prevalence differences, the study was conducted over four seasons: that is, 60 inpatients were randomly selected to join the research every 3 months. Starting on the first workday of each season, two specific researchers observed newly admitted patients and identified eligible patients. Before determining the physician in charge, eligible patients were contacted by the two specific researchers. Upon contact, the researchers informed the patients about this study opportunity and invited them to participate. Patients who consented verbally and completed the consent form were included in the study and then randomly assigned to one of the six doctors for treatment. After the primary diagnosis and treatment were determined, within 48 h after admission, the patients were randomized to the experimental group (model-based communication group) or control group (pictures-based communication group) by the two researchers, using a random number table. The doctor in charge then conducted communication according to the protocol of each group. In the model-based communication group, the surgeons were required to take advantage of the model’s anatomy or demonstrating function while explaining the region and cause of a lesion, the possible progress of the disease, and the therapies and surgical procedures that were planned or being conducted. Because the model is transparent, the patients can observe the internal anatomical structure and various operating states inside. shows one doctor explaining the purpose and method of ureteral stent insertion to a patient. shows the stent in the model. In the picture-based group, the surgeons were asked to use the model-design pictures to conduct communication without the model. The communication content of the groups referenced the research of Hagihara and TarumiCitation16 and primarily included, 1) the medical testing and examination; 2) the cause and diagnosis; 3) the treatment and its effects; 4) the side effect and treatment risks; and 5) the prognosis of the disease and patient precautions: the time for communicating was 20 min. Each season’s study continued until the research task was accomplished with 60 patients.

Measures and statistical analyses

Within 30 min after the communication and in the absence of the physician, the two specific researchers conducted a questionnaire investigation. The patients were asked to complete a Demographic Information Survey Scale to elicit demographic information, including sex, age, level of education, first diagnosis, and whether the occurrence was the first hospitalization, and they were required to complete the Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale (MISS) (Supplementary materials).Citation17,Citation18 The MISS consisted of 29 questions that provided a measure of overall patient satisfaction, and its four subscales can be used to assess, 1) distress relief, 2) communication comfort, 3) rapport, and 4) compliance intent. All subjects were asked to provide an opinion on a 7-point Likert scale for each question, with the answer “very strongly disagree” at 1 and the answer “very strongly agree” at 7. The subscale and total scores were calculated by simply adding all item scores without weighting; thus, the qualitative assessment had a potential minimal score of 29 and a maximum of 203 points. The results were sent to the research group: another two researchers independently conducted the data analysis and statistics with SPSS software, version 10.0. The differences in the demographic information and the evaluation were compared using the chi-square test or the independent-samples t-test. Statistical significance was accepted at P<0.05.

Results

Participants

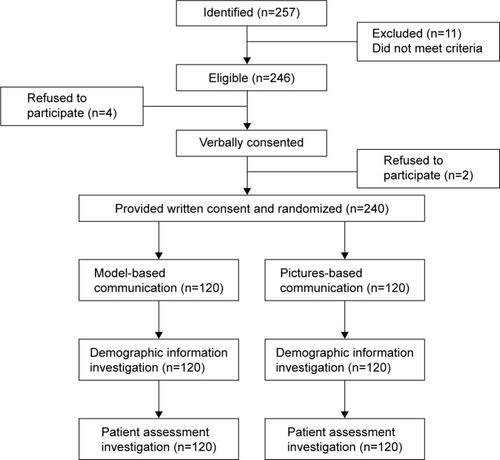

Of the six surgeons, one (male) was a chief physician, and two (males) were associate chief physician and attending physician, and three were residents (two males and one female). The average age of the surgeons was 36 years (SD 9.84; range 27–49), and the average career length was 11.17 years (SD 9.79; range 3–24). The six doctors were eligible to participate in the study. All of these individuals completed every procedure in strict accordance with the study program and consented to allowing images obtained during this study to be used in this article, and none of the doctors dropped out at the halfway point of the trial. A total of 257 inpatients were identified, of whom 246 were eligible. A total of 240 inpatients voluntarily participated in the research: 120 in the experimental group and 120 in the control group, and all of the patients consented to the inclusion of their data in the analysis. shows the participant flow of the randomized controlled trial.

Demographic characteristics

Of the patients in the experimental group, 80 were males () and 40 were females: 20 were aged 18–32 years, 35 were aged 33–47 years, 39 were aged 48–62 years, and 26 were aged ≥63 years; 49 had less than a middle school education, 37 had a middle school or a high school education, and 34 had more than a high school education; 19 patients had renal failure, 49 had urolithiasis, 23 had obstruction of the urinary tract, 18 had tumors, and 11 had other medical conditions; 76 stated it was their first hospitalization, and 44 had been hospitalized more than once. In the control group, 85 were males and 35 were females: 14 were aged 18–32 years, 33 were aged 33–47 years, 36 were aged 48–62 years, and 37 were aged ≥63 years; 57 had less than a middle school education, 22 had a middle school or a high school education, and 41 had more than a high school education; 26 patients had renal failure, 38 had urolithiasis, 29 had obstruction of the urinary tract, 21 had tumors, and 6 had other medical conditions; 74 stated it was their first hospitalization, and 36 had been hospitalized more than once. According to the Chi-square test, no differences were determined between the groups with regard to sex (χ2=0.485, P=0.486), age divisions (χ2=3.158, P=0.368), levels of education (χ2=2.223, P=0.329), illness categories (χ2=4.873, P=0.301), or whether it was a first or subsequent hospitalization (χ2=0.071, P=0.790).

Table 1 Demographic characteristics

Patient assessment

In the evaluation survey, the model-based communication group and pictures-based communication group received means of 148.44±18.97 and 141.66±20.92 (P=0.009), respectively, in terms of total satisfaction (). Additionally, on the MISS subscales, the experimental group and the control group scored 56.04±6.46 and 53.88±7.43 (P=0.017) for distress relief, 19.92±2.96 and 18.55±3.51 (P=0.001) for communication comfort, 52.25±7.75 and 49.96±8.94 (P=0.035) for rapport, and 20.23±2.93 and 19.27±3.42 (P=0.019) for compliance intent. All of the rating scores from the experimental group were higher than those from the control group ().

Table 2 Impact of intervention on patient and doctor satisfaction

Discussion

Medicine involves the integration of not only art and science but also magic and creative ability, and the building of a harmonious patient–physician relationship reflects this artistic quality.Citation19,Citation20 Research focusing on the concerns of clinical physicians has been extensive. Studies have found that attentive and respectful listening in communication reinforced the healing process and positively affected patient satisfaction;Citation21–Citation23 theater training was effective at teaching clinical empathy;Citation24 empathic responses during doctor–patient information exchanges were consistently associated with positive patient outcome, stable patient adherence, and symptom resolution;Citation25–Citation30 a physician’s attention to a computer monitor diminished dialogue between the physician and the patient and was inversely correlated with the effect of communication;Citation31 and audiovisual aids, such as figures, pictures, DVDs, and MP3 files, were helpful for transferring medical information, promoting doctor–patient communication, and improving patient comprehension, recall, and adherence.Citation32–Citation35 To our knowledge, there have been few or no studies with regard to the effectiveness of a simulator or anatomic model in promoting doctor–patient communication and improving patient outcomes.

This article, along with randomized, controlled trials, compared the content validity of a novel urinary system-simulating physical model with that of pictures in improving doctor–patient communication and patient satisfaction. In our experimental design, we found that patients of different sexesCitation36–Citation40 and with different hospitalization frequencies,Citation36 ages,Citation41–Citation43 education levels,Citation44 and health conditionsCitation45 had diverse needs in communication and different opinions when evaluating doctors and their own patient satisfaction; thus, these patient characteristics influenced clinical communication. In this research, it was demonstrated that there was no significant difference in the aspects cited above when comparing the experimental group to the control group according to the statistical data, and almost all of the interventions that might have affected the research results were excluded, ensuring that our results and conclusions were objective and reliable.

Consequently, the significant differences in the evaluations between the experimental and control groups indicated that the following conclusions can be drawn: model-based communication seems to be more effective in affecting patient satisfaction, promoting patient distress relief, increasing communication comfort, enhancing patient compliance, strengthening doctor–patient relationship, and improving patient outcomes compared to picture-based communication. These results were consistent with our expectations. It is well known that relative to dissatisfied patients, satisfied patients are less likely to lodge formal complaints or initiate malpractice proceedings;Citation19,Citation46–Citation48 moreover, patient satisfaction is advantageous for doctors with respect to increased job satisfaction, reduced fatigue, and relief from work-related stress.Citation1,Citation49 As a result, it can reduce the litigation costs of hospitals and promote the development of a harmonious and stable medical environment, and it is beneficial to hospitals, clinical medicine, and medical research. Along with its effectiveness in improving patient outcomes, which reduces expenses for patients, model-based communication can benefit both the medical practice and the patients.

When considering the factors that led to the significant difference observed between the two groups, we speculated that the authenticity of the model played an important role. During a patient consultation, the use of the physical model to explain and analyze diseases and treatments is more intuitive and vivid than the use of pictures, which provide less direct representations. As a result, model use enhanced patients’ understanding of medical information and relieved patient distress.

Actually, it was appropriate to expand the study values in light of the entire article, and the important attributes of the model used were anatomically accurate, with a functional presentation. This study hypothesizes that other simulation models of the urinary system or simulators of other systems will also be useful in related clinical departments to increase patient satisfaction and improve patient compliance and outcomes.

Another advantage of model-based communication was its convenience in generalization and application. First, this physical model was economical and easy to fabricate. Moreover, other physical simulation models are convenient to purchase because many economical simulators and anatomical models exist on the market. Furthermore, model-based communication was easy to implement in the clinic, with no particular training required. If the doctor was familiar with the structure and function of a simulator, he or she could undertake interactive and vivid communication with patients soon. This was extremely meaningful, particularly in geographic areas with poor education and training in communication skills, and model-based communication could be used to alleviate doctor–patient conflicts and to ameliorate effectively and promptly the tensions of the doctor–patient relationship. Admittedly, useful communication skills are essential in clinical communication, but we firmly believe that model-based communication can serve as a supplementary approach to improve the quality of communication and health care.

One limitation of this study was that the number of doctors included in the trials was insufficient, and although it included chief physicians, associate chief physicians, attending physicians and residents, the number of physicians at each level was limited. Another limitation was that it was not clear whether the application of the model enhanced the patients’ recall of the necessary information. In addition, it cannot be determined which type of doctor this communication mode was more beneficial for, nor the type of patients for whom this communication mode was more applicable. We will conduct further research on these issues.

Conclusion

Our study designed and fabricated a novel urinary system-simulating physical model. The model’s content validity in improving doctor–patient communication was confirmed by comparing its use with the use of pictures. This comparison demonstrated that the application of the physical model was more effective in promoting doctor–patient communication, relieving patient distress, enhancing patient compliance, strengthening the doctor–patient relationship, and improving patient outcomes, compared to the pictures. With demonstrated effectiveness in improving patient satisfaction and convenience of application, model-based communication merits widespread popularization. It could be used to alleviate doctor–patient conflicts and to effectively ameliorate the tensions of the doctor–patient relationship.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank MingQi Fan for assistance with statistical analysis and RongHua Wu and YiRong Chen for participating in the study. The authors also gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Scientific and Technological Achievements Fund (2011XZH05, 2012XZH04) and the Clinical Research Fund of the Third Military Medical University of China (2008XLC15).

Supplementary materials

Questionnaire investigation

Scale 1. Demographic Information Survey Scale

| 1. | Sex. | ∅ |

| ∅ | Male Female | ∅ |

| 2. | Age. | ∅ |

| ∅ | 18–32 33–47 48–62 | ≥63 |

| 3. | Level of education. | ∅ |

| ∅ | Less than middle school | Middle school to high school More than high school |

| 4. | The first diagnosis. | ∅ |

| ∅ | Renal failure Urolithiasis | Obstruction Tumor Other |

| 5. | First hospitalization or not. | ∅ |

| ∅ | First Not the first | ∅ |

Scale 2. The Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale (MISS)

| 1. | The doctor gave me a poor explanation of my illness. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 2. | The doctor told me what my illness is. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 3. | After talking to the doctor, I know how serious my illness is. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 4. | The doctor told me all I wanted to know about my illness. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 5. | I am not really certain how to follow the doctor’s advice. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 6. | After talking to the doctor, I have an idea of how long it will take for me to get cured from the illness | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 7. | The doctor seemed interested in me as a person. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 8. | The doctor seemed warm and friendly to me. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 9. | I felt this doctor did not treat me as an equal. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 10. | The doctor seemed to take my problems seriously. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 11. | I felt embarrassed while talking to the doctor. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 12. | I felt free to talk to this doctor about private matters. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 13. | The doctor gave me a chance to say what was really on my mind. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 14. | I really felt understood by my doctor. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 15. | The doctor did not allow me to say everything I had wanted to say about my problems. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 16. | The doctor did not really understand my reason for coming. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 17. | I would trust this doctor with my life. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 18. | I would hesitate to recommend this doctor to my friends. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 19. | The doctor seemed to know what he/she was doing. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 20. | After talking to the doctor, I feel much better about my problems. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 21. | The doctor has relieved my worries about my illness. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 22. | Talking to my doctor has not at all helped me be relieved of my worries about my illness. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 23. | The doctor has come up with a good plan for helping me. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 24. | The doctor’s visit has not at all helped me. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 25. | The doctor seemed to know what to do for my problem. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 26. | I expect that it will be easy for me to follow the doctor’s advice. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 27. | I intend to follow the doctor’s instructions. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 28. | It may be difficult for me to do exactly what the doctor has told me to do. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

| 29. | I am not sure the doctor’s treatment will be worth the trouble it will take. | |||

| ∅ | Very strongly agree | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral |

| ∅ | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Very strongly disagree | ∅ |

Subscales

| MISS1 | Distress relief | Qs 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 |

| MISS2 | Communication comfort | Qs 5, 11, 15, 16 |

| MISS3 | Rapport | Qs 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 17, 18, 19 |

| MISS3 | Compliance intent | Qs 26, 27, 28, 29 |

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BrédartABouleucCDolbeaultSDoctor-patient communication and satisfaction with care in oncologyCurr Opin Oncol200517435135415933466

- AroraNKInteracting with cancer patients: the significance of physicians’ communication behaviorSoc Sci Med200357579180612850107

- LeeSJBackALBlockSDStewartSKEnhancing physician-patient communicationHematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program200246448312446437

- PlattFWKeatingKNDifferences in physician and patient perceptions of uncomplicated UTI symptom severity: understanding the communication gapInt J Clin Pract200761230330817263717

- FristWHShattuck lecture: health care in the 21st centuryN Engl J Med2005352326727215659726

- BrownJBBolesMMulloolyJPLevinsonWEffect of clinician communication skills training on patient satisfaction. A randomized, controlled trialAnn Intern Med19991311182282910610626

- PendletonLHouseWCParkerLEPhysicians’ and patients’ views of problems of compliance with diabetes regimensPublic Health Rep1987102121263101117

- RichardsTChasms in communicationBMJ19903016766140714082279152

- StewartMAEffective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a reviewCMAJ19951529142314337728691

- WilliamsSWeinmanJDaleJDoctor-patient communication and patient satisfaction: a reviewFam Pract19981554804929848436

- JenkinsLBrittenNStevensonFBarberNBradleyCDeveloping and using quantitative instruments for measuring doctor-patient communication about drugsPatient Educ Couns200350327327812900099

- LefevreFVWatersTMBudettiPPA survey of physician training programs in risk management and communication skills for malpractice preventionJ Law Med Ethics200028325826611210378

- LevinsonWPhysician-patient communication. A key to malpractice preventionJAMA199427220161916207646617

- ShapiroRSSimpsonDELawrenceSLTalskyAMSobocinskiKASchiedermayerDLA survey of sued and nonsued physicians and suing patientsArch Intern Med198914910219021962802885

- HuWGFengJYWangJUreteroscopy and cystoscopy training: comparison between transparent and non-transparent simulatorsBMC Med Educ2015159326032174

- HagiharaATarumiKDoctor and patient perceptions of the level of doctor explanation and quality of patient-doctor communicationScand J Caring Sci200620214315016756519

- KinnersleyPStottNPetersTHarveyIHackettPA comparison of methods for measuring patient satisfaction with consultations in primary careFam Pract199613141518671103

- WolfMHPutnamSMJamesSAStilesWBThe Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale: development of a scale to measure patient perceptions of physician behaviorJ Behav Med197814391401755868

- HaJFLongneckerNDoctor-patient communication: a reviewOchsner J2010101384321603354

- HallJARoterDLRandCSCommunication of affect between patient and physicianJ Health Soc Behav198122118307240703

- ClarkNMCabanaMDNanBThe clinician-patient partnership paradigm: outcomes associated with physician communication behaviorClin Pediatr (Phila)2008471495717901215

- JagoshJDonald BoudreauJSteinertYMacdonaldMEIngramLThe importance of physician listening from the patients’ perspective: enhancing diagnosis, healing, and the doctor-patient relationshipPatient Educ Couns201185336937421334160

- WanzerMBBooth-ButterfieldMGruberKPerceptions of health care providers’ communication: relationships between patient-centered communication and satisfactionHealth Commun200416336338315265756

- DowAWLeongDAndersonAWenzelRPTeam VT-MUsing theater to teach clinical empathy: a pilot studyJ Gen Intern Med20072281114111817486385

- HojatMLouisDZMarkhamFWWenderRRabinowitzCGonnellaJSPhysicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patientsAcad Med201186335936421248604

- KelleyJMLemboAJAblonJSPatient and practitioner influences on the placebo effect in irritable bowel syndromePsychosom Med200971778979719661195

- KimSSKaplowitzSJohnstonMVThe effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and complianceEval Health Prof200427323725115312283

- LangewitzWNüblingMWeberHA theory-based approach to analysing conversation sequencesEpidemiol Psichiatr Soc200312210310812916451

- SquierRWA model of empathic understanding and adherence to treatment regimens in practitioner-patient relationshipsSoc Sci Med19903033253392408150

- ZimmermannCdel PiccoloLMazziMAPatient cues and medical interviewing in general practice: examples of the application of sequential analysisEpidemiol Psichiatr Soc200312211512312916453

- MargalitRSRoterDDunevantMALarsonSReisSElectronic medical record use and physician-patient communication: an observational study of Israeli primary care encountersPatient Educ Couns200661113414116533682

- ShawAIbrahimSReidFUssherMRowlandsGPatients’ perspectives of the doctor-patient relationship and information giving across a range of literacy levelsPatient Educ Couns200975111412019041210

- BinettiPMeloniMCDenaroV[New prospects in physician-patient communication: role of the animated model] [Article in Italian]Clin Ter2003154642142814994523

- CollierREducating patients with picturesCMAJ201118315E109421911552

- KoolsMvan de WielMWRuiterRAKokGPictures and text in instructions for medical devices: effects on recall and actual performancePatient Educ Couns2006641–310411116472960

- BondsDEFoleyKLDuganEHallMAExtromPAn exploration of patients’ trust in physicians in trainingJ Health Care Poor Underserved200415229430615253380

- DeroseKPHaysRDMcCaffreyDFBakerDWDoes physician gender affect satisfaction of men and women visiting the emergency department?J Gen Intern Med200116421822611318922

- Elderkin-ThompsonVWaitzkinHDifferences in clinical communication by genderJ Gen Intern Med199914211212110051782

- SandhuHAdamsASingletonLClark-CarterDKiddJThe impact of gender dyads on doctor-patient communication: a systematic reviewPatient Educ Couns200976334835519647969

- WaitzkinHInformation giving in medical careJ Health Soc Behav1985262811014031436

- BeiseckerAEAging and the desire for information and input in medical decisions: patient consumerism in medical encountersGerontologist19882833303353396915

- ThompsonSCPittsJSSchwankovskyLPreferences for involvement in medical decision-making: situational and demographic influencesPatient Educ Couns19932231331408153035

- VickSScottAAgency in health care. Examining patients’ preferences for attributes of the doctor-patient relationshipJ Health Econ199817558760510185513

- TuckettDABoultonMOlsonCA new approach to the measurement of patients’ understanding of what they are told in medical consultationsJ Health Soc Behav198526127383998432

- AroraNKMcHorneyCAPatient preferences for medical decision making: Who really wants to participate?Med Care200038333534110718358

- BrinkmanWBGeraghtySRLanphearBPEffect of multi-source feedback on resident communication skills and professionalism: a randomized controlled trialArch Pediatr Adolesc Med20071611444917199066

- O’KeefeMShould parents assess the interpersonal skills of doctors who treat their children? A literature reviewJ Paediatr Child Health200137653153811903829

- TongueJREppsHRForeseLLCommunication skillsInstr Course Lect2005543915948430

- MaguirePPitceathlyCKey communication skills and how to acquire themBMJ2002325736669770012351365