Abstract

Background

Antipsychotic medication reduces the severity of serious mental illness (SMI) and improves patient outcomes only when medicines were taken as prescribed. Nonadherence to the treatment of SMI increases the risk of relapse and hospitalization and reduces the quality of life. It is necessary to understand the factors influencing nonadherence to medication in order to identify appropriate interventions. This systematic review assessed the published evidence on modifiable reasons for nonadherence to antipsychotic medication in patients with SMI.

Methods

Articles published between January 1, 2005, and September 10, 2015, were searched on MEDLINE through PubMed. Abstracts were independently screened by 2 randomly assigned authors for inclusion, and disagreement was resolved by another author. Selected full-text articles were divided among all authors for review.

Results

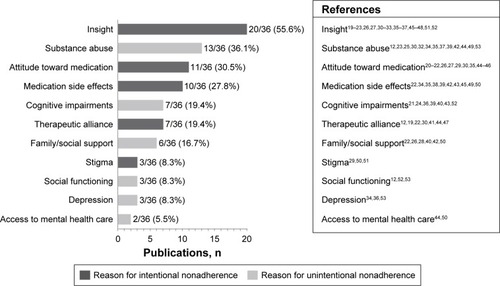

A qualitative analysis of data from 36 articles identified 11 categories of reasons for nonadherence. Poor insight was identified as a reason for nonadherence in 55.6% (20/36) of studies, followed by substance abuse (36.1%, 13/36), a negative attitude toward medication (30.5%, 11/36), medication side effects (27.8%, 10/36), and cognitive impairments (13.4%, 7/36). A key reason directly associated with intentional nonadherence was a negative attitude toward medication, a mediator of effects of insight and therapeutic alliance. Substance abuse was the only reason consistently associated with unintentional nonadherence, regardless of type and stage of SMI.

Discussion

Although adherence research is inherently biased because of numerous methodological limitations and specific reasons under investigation, reasons for nonadherence consistently identified as significant across studies likely reflect valid existing associations with important clinical implications.

Conclusion

This systematic review suggests that a negative attitude toward medication and substance abuse are consistent reasons for nonadherence to antipsychotic medication among people with SMI. Adherence enhancement approaches that specifically target these reasons may improve adherence in a high-risk group. However, it is also important to identify drivers of poor adherence specific to each patient in selecting and implementing intervention strategies.

Introduction

Antipsychotic medication reduces the severity of serious mental illness (SMI) and improves patient outcomes. A meta-analysis of 65 clinical trials in patients with schizophrenia stabilized on antipsychotic medication who were randomized to continue the treatment or switch to placebo showed that treatment with antipsychotics significantly reduces rates of relapse.Citation1 A meta-analysis of 6 placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials in patients with acute schizophrenia treated with antipsychotics demonstrated a significant improvement in positive and negative symptoms over 6 weeks, with proportionately increasing treatment effect in those with more severe symptoms at baseline.Citation2 A meta-analysis of 12 randomized clinical trials assessing acute mania (in bipolar disorder) showed that antipsychotic monotherapy significantly improved mania symptoms compared with placebo.Citation3 However, medication is effective only when it is actually ingested, and nonadherence is a major impediment to effective treatment in patients with SMI. It should be noted that atypical antipsychotic drugs are currently only approved as adjunctive therapy for patients with major depressive disorder (MDD).Citation4–Citation6

Rates of partial adherence or nonadherence with foundational psychopharmacologic treatments in SMI vary but are estimated to be at least 40%–50%.Citation7,Citation8 In addition, it is difficult to maintain adherence over time (often referred to as persistence), and rates of nonadherence further worsen with longer observation periods. For example, a 4-year retrospective, cross-sectional study from a large cohort of patients with schizophrenia from the US Department of Veterans Affairs found that ~36% of patients were poorly adherent in each year and that 61% had adherence problems at some point during the 4-year period.Citation9

Ongoing adherence to antipsychotics is critical for optimal outcomes in patients with SMI. Interruption of treatment as short as 1–10 days has been associated with an increased risk of hospitalization in patients with schizophrenia.Citation10 In addition to hospitalization, medication nonadherence has been associated with an increased use of emergency psychiatric services, violence, arrests, an increased risk of suicide attempt, poor social and occupational functioning, and reduced quality of life.Citation11–Citation13 Interventions to improve adherence have the potential to reduce these risks, but it seems unlikely that a “one size fits all” approach to enhance adherence with foundational medications is appropriate for all or even most patients with SMI. To develop and deliver person-centered care that is evidence-based and tailored to address specific adherence problems,Citation14 it is necessary to identify and understand the most common and potentially modifiable reasons influencing medication nonadherence. For example, for a patient with both poor insight into disease and poor attitude toward medication, cognitive behavioral therapy would be a more suitable treatment than a long-acting injectable antipsychotic. A psychosocial intervention customized by identified reasons for nonadherence (customized adherence enhancement) has demonstrated improvement in adherence, symptoms, and functioning of patients with bipolar disorder.Citation15

Although people with SMI often receive various psychotropic medications, antipsychotic drugs are a common therapeutic strategy in a number of chronic psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder, and are used as adjunctive treatment to antidepressants in major depression. This systematic review assessed the published evidence related to each individual potentially modifiable reason affecting adherence to antipsychotic medication in patients with SMI, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and MDD.

Methods

Information source and eligibility criteria

This review was conducted on the basis of recommendations outlined by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.Citation16 English-language articles published between January 1, 2005, and September 10, 2015, in peer-reviewed journals were searched on MEDLINE through PubMed using the following string of key terms: (MDD OR “major depressive disorder” OR schizophrenia OR “bipolar disorder”) AND (“adherence” OR “nonadherence” OR “non-adherence” OR “compliance” OR “noncompliance” OR “non-compliance”) AND (“risk” OR “reason”) AND English [Language] AND (“2005/01/01” [Date – Publication]: “3000” [Date – Publication]) NOT review (ptyp). Eligible studies reported at least 1 potentially modifiable risk factor/reason for adherence or nonadherence to prescribed antipsychotic medication in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or MDD identified during clinical interaction (ie, reasons that were reported by the patient, health care professional [HCP], or family). HCPs included physicians and case managers. Studies reporting only nonmodifiable reasons (eg, sociodemographic characteristics) were excluded. Modifiable reasons include those that can potentially be addressed clinically or through psychosocial intervention, whereas nonmodifiable reasons are those considered to be inherent to the individual (eg, age, sex, and ethnicity). Review articles, editorials, and articles reporting results from method development, such as psychometric properties of an instrument, were also excluded.

Article selection process

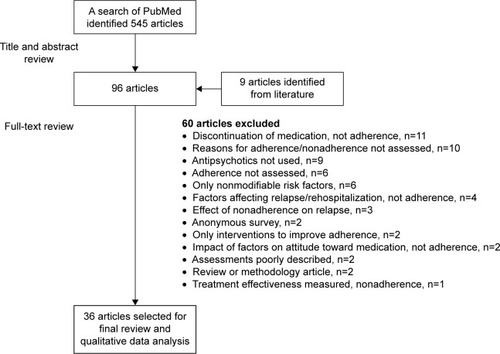

The title and abstract of each retrieved article were independently screened by 2 randomly assigned authors. Instances of disagreement about inclusion was resolved by a third author. Selected full-text articles were divided among all authors for detailed review and assessed for inclusion based on predefined eligibility criteria. shows the process of article selection.

Results

Article selection

A total of 545 articles were retrieved through the search; 458 articles were excluded following screening of titles and abstracts, and 87 articles were selected for a full-text review. Screening of references from 2 published reviews on medication adherence/nonadherence in schizophrenia-spectrum disordersCitation17,Citation18 found 9 potentially relevant articles not identified by the search (missing the term “risk” or “reason” in title/abstract); the full text of these articles was also reviewed. Thirty-six articles met the eligibility criteria and were included in the qualitative data analysis ().

Characteristics of selected studies

Nineteen studies of the final selected reports were cross-sectional (52.8%, 19/36), including 3 surveys; 11 were prospective observational studies or clinical trials (30.6%, 11/36); and 6 were post hoc analyses of data from prospective studies or clinical trials (16.7%, 6/36). A brief summary of results from each of the studies is provided in and Citation12,Citation19–Citation34 (prospective and post hoc analyses) and and Citation35–Citation53 (cross-sectional). Most of the studies were conducted in patients with schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like disorders (75%, 27/36). An additional 3 studies were conducted in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, 4 in patients with bipolar disorder, and 2 in patients with SMI that also included MDD. Studies from Europe, the United States, or Canada comprised 75% (27/36) of the group. An additional 4 studies were from Asia, 3 from Africa, and 1 each from Australia and Israel. Most of the studies (88.9%, 32/36) were published between 2006 and 2013, with a range of 3–6 studies published each year during that period. Insight was the most frequently investigated reason for nonadherence, reported in 55.6% (20/36) of the studies, followed by substance abuse (36.1%, 13/36), attitude toward medication (30.5%, 11/36), medication side effects (27.8%, 10/36), and cognitive impairments (19.4%, 7/36; Citation12,Citation19,Citation20,Citation22–Citation36,Citation38–Citation50,Citation52–Citation55).

Table 1 Reasons for nonadherence to antipsychotic medication in patients with SMI: summary of methods used in prospective studies

Table 2 Reasons for nonadherence to antipsychotic medication in patients with SMI: results of prospective studies

Table 3 Reasons for nonadherence to antipsychotic medication in patients with SMI: summary of methods used in cross-sectional observational studies

Table 4 Reasons for nonadherence to antipsychotic medication in patients with SMI: results of cross-sectional observational studies

Findings from individual studies

The identified reasons for nonadherence were divided into 2 groups (intentional and unintentional), reflecting the contrast between personal choice of patients and objective barriers to taking medication. Defining reasons in this way may be useful for identifying or developing appropriate adherence enhancement intervention strategies.

Reasons for intentional nonadherence

Intentional nonadherence refers to a conscious patient decision to stop taking medication or to take less medication than is prescribed. The identified reasons in this category include poor insight, a negative attitude toward medication, distressing medication side effects, poor therapeutic alliance, and stigma.

Insight

A total of 20 studies analyzed the relationship between insight and adherence; of which 11 were prospective ( and ) and 9 were cross-sectional ( and ). Instruments used in most of the studies measured at least 2 domains of insight: awareness of illness, and awareness of need for treatment. Results were expressed as a combined insight score or separately for each domain.

Prospective studies

In patients with schizophrenia, including a first-episode illness, poor insight was a significant predictor of nonadherenceCitation21,Citation32 and was associated with a shorter time to medication discontinuation.Citation31 Another study in patients with schizophrenia reported that baseline scoring on a standardized insight scaleCitation56 differed significantly between adherent and nonadherent patients.Citation33 Better insight reflected by scores in 3 insight domains was associated with improved adherence in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.Citation19 In bipolar disorder, poor insight after acute mania treatment was associated with a greater probability of nonadherence during maintenance therapy.Citation23 Two reports that did not show a significant association between insight and adherence were studies in first-episode psychosis that assessed insight from a single item on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).Citation26,Citation30

Cross-sectional studies

Poor insight was significantly associated with nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia,Citation48 with first-episode schizophrenia and related disorders,Citation45 and in patients aged >50 years with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or MDD.Citation52 Mean scores on an insight scaleCitation57 were significantly greater (indicating improved insight) in patients with schizophrenia who were fully adherent compared with those who were nonadherent, but the association was on a trend level and not statistically significant in patients with bipolar disorder.Citation37 When a specific domain of insight was assessed, awareness of need for treatment but not awareness of illness was significantly associated with adherence in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.Citation47 Similarly, poor awareness of need for treatment was associated with poor adherence in Korean patients with chronic schizophrenia.Citation36 In contrast, a study from Ethiopia found that awareness of illness and ability to positively reassess experiences/symptoms, but not awareness of need for treatment, were associated with better adherence in patients with schizophrenia.Citation35 In a survey of European clinicians, lack of insight into the need for prophylactic medication and lack of insight into illness were the most frequently cited reasons for partial adherence in schizophrenia.Citation51

Attitude toward medication

Eleven studies analyzed the relationship between medication adherence and attitude toward medication. All demonstrated a significant positive association wherein negative attitudes were associated with poor adherence. Seven studies were prospective ( and ) and 4 were cross-sectional ( and ). The instrument used most frequently to assess attitude toward medication was the Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI, 54.5%, 6/11).Citation58

Prospective studies

In 2 studies of patients with first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses, poor early medication acceptance at study entryCitation26 and hostility and uncooperativeness at first admissionCitation30 were the most significant predictors of nonadherence.Citation26,Citation30 These results support the common clinical impression that the patient’s early attitude toward medication impacts adherence and persists throughout the treatment. It is of note that prior nonadherence was the best predictor of nonadherence in 2 large studies of patients with schizophrenia.Citation12,Citation34 However, this phenomenon indicates predictability of future behavior based on past behavior and may be driven by other reasons (eg, those associated with unintentional nonadherence) in addition to attitude toward medication.

A positive attitude toward medication at baseline in combination with good psychosocial function was the best predictor of objectively measured mean adherence over a 12-month period in patients with schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like psychosis.Citation20 A post hoc analysis of data from a large clinical trial in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder reported that perceived medication benefit was the only significant predictor of early treatment discontinuation.Citation29 An analysis of data from another large clinical trial of patients with schizophrenia (CATIE) found that a positive attitude toward medication at baseline was associated with better adherence, and a change toward a more positive attitude improved adherence during the study.Citation27 Of note, a best-fitting model to explain nonadherence included attitude toward medication but not insight into need for the treatment and awareness of illness.Citation27 In contrast, results from a study of Chinese patients with schizophrenia showed that attitude toward medication was not required in a model that predicted nonadherence and included measures of insight and symptom severity; however, patients who were nonadherent had significantly worse attitudes toward medication compared with those who were adherent at follow-up.Citation21 A more detailed analysis identified attitude toward medication as a mediator of 2 domains of insight: awareness of consequences of illness and awareness of the need for medication.Citation22 In that study, adherence of patients with early-episode schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder 6 months after hospital discharge was directly predicted by attitude toward medication, symptom severity, and early stage of the illness but not by insight.

Cross-sectional studies

An Ethiopian study found that negative attitude toward medication was significantly associated with nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia.Citation35 A Chinese study in first-episode schizophrenia found a similar association,Citation45 as did a study in US veterans with bipolar disorder.Citation44 A study of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder showed that attitude toward antipsychotic medication comprised dimensions of “necessity” and “concerns” that impact adherence directly and independently of each other. These 2 dimensions differ from attitude toward pharmacotherapy in general, which was not found to be a direct predictor of adherence.Citation46

Relationship between insight and attitude toward medication

A longitudinal analysis of adherence from a large prospective study of patients with schizophrenia showed that baseline insight measured as awareness of illness and awareness of need for treatment was significantly associated with adherence only in a model that did not include a measure of attitude toward medication.Citation27 Similarly, in patients with schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like psychosis, poor awareness of illness was a significant predictor of nonadherence in a univariate analysis but was not required for the best model fit in a multivariable model that included a measure of attitude toward medication.Citation20 Better awareness of illness and awareness of need for treatment were associated with better adherence in early schizophrenia, although the 2 domains of insight were predictors of attitude toward medication, which in turn was a direct predictor of adherence.Citation22 Similar results were obtained from a cross-sectional study of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder using a structural equation model.Citation46 In that model, the relationship between insight (awareness of illness and social consequences of illness) and adherence was mediated by attitude toward medication, specifically by the dimension of perceived necessity for treatment.Citation46

Medication side effects

Ten studies analyzed the relationship between medication side effects and adherence: 2 were prospective and 8 were cross-sectional. In a large prospective study of patients with schizophrenia, patient-reported cognitive impairment resulting from antipsychotic medication was included among the 5 strongest predictors of nonadherence.Citation34 Conversely, patients with early schizophrenia who were adherent 6 months after discharge from the hospital experienced significantly more severe side effects compared with patients who were nonadherent.Citation22

Results from a US nationwide cross-sectional survey of patients with schizophrenia identified 4 categories of side effects that were each associated with significantly less adherent behavior.Citation38 Experiencing greater side effects was significantly associated with worse adherence in Ethiopian patients with schizophrenia.Citation35,Citation39 In another study of patients with schizophrenia, having side effects was among 3 independent variables included in a model that predicted nonadherence of patients in Australia.Citation50 Having side effects was also among 3 independent variables in a model predicting nonadherence of patients with SMI who had a recent history of substance abuse or addictionCitation42 and the second most common reason for nonadherence identified in poorly adherent patients with bipolar disorder.Citation43 Results from a nationwide US survey of physicians and their patients with bipolar disorder showed that having side effects was among 6 categories of independent variables significantly associated with nonadherence; weight gain was a side effect most frequently linked to nonadherence by patients who identified themselves as nonadherent.Citation49 Interestingly, a perceived but not actual overweight status was associated with poor adherence and was among the 3 most influential factors contributing to nonadherence of Chinese patients with first-episode schizophrenia and related disorders.Citation45

Therapeutic alliance

Therapeutic alliance is a broad concept denoting the quality of relationship between patient and clinician. Seven studies, 4 prospective and 3 cross-sectional, analyzed the association between therapeutic alliance and adherence. Physician-reported therapeutic alliance was strongly correlated with adherence at baseline, and improved therapeutic alliance was correlated with improved adherence after 1 year of follow-up based on a post hoc analysis of data from a prospective, observational study of patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.Citation19 In another prospective observational study, better patient-reported therapeutic alliance at baseline was associated with better adherence of patients with early-episode schizophrenia 6 months after hospital discharge.Citation22 However, the variable was not required in a best-fitting model predicting adherence that included attitude toward medication, symptom severity, and stage of illness.Citation22 For patients with first-episode schizophrenia and related disorders, the only significant predictor of nonadherence during a 5-year follow-up study was negative therapeutic alliance, which was assessed based on the level of hostility and uncooperativeness at admission and involuntary admission.Citation30 Hostility was also among significant baseline predictors of nonadherence over 3 years based on a post hoc analysis of data from a prospective observational study of patients with schizophrenia.Citation12

Results from a cross-sectional study conducted to examine the relationship between therapeutic alliance and adherence of patients with schizophrenia or related disorders reported that patient- and physician-reported measures of therapeutic alliance, although only weakly correlated, were both independently and significantly associated with adherence. However, no other variables were assessed in that study except for symptom severity.Citation41 Low level of patient-reported therapeutic alliance was a significant predictor of poor attitude toward medication, which was used as a proxy for nonadherence in a cross-sectional study of patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.Citation47 In contrast, poor therapeutic alliance was not a significant predictor of nonadherence in a model that included negative medication beliefs, binge drinking, and limited access to a mental health specialist in a cross-sectional study of US veterans with bipolar disorder.Citation44

Stigma

Stigma refers to a feeling of disgrace because of mental illness and/or need for treatment.Citation59 Three studies assessed stigma in relation to adherence. In a cross-sectional, 10- question survey of physicians, stigma was among the 3 reasons most frequently considered as contributing to poor adherence of patients with schizophrenia.Citation51 Stigma was not among 3 variables that predicted nonadherence in a cross-sectional study of patients with schizophrenia in Australia, although ~70% of the patients indicated a feeling of stigma.Citation50 A post hoc analysis from a large clinical trial of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder did not identify stigma as a variable significantly predicting early treatment discontinuation.Citation29

Reasons for unintentional nonadherence

Unintentional nonadherence occurs when practical problems or impairments related to having SMI interfere with taking medication. Unintentional nonadherence affects a patient’s ability to take medication on a regular basis. Using this definition, the following reasons for nonadherence were included in this category: substance abuse, cognitive impairments, depression, family/social support, access to mental health care, and social functioning. Substance abuse was included in this category because a patient’s nonadherence to medication is unintentional during the period of substance use.

Substance use or abuse

Thirteen studies analyzed the relationship between substance abuse and adherence: 6 were prospective, 7 were cross-sectional, and all demonstrated a significant association.

Prospective studies

In first-episode schizophrenia or related disorders, misuse of alcohol at baseline and recent drug abuse were significant predictors of nonadherence within 6 months from the patients’ first episode.Citation32 Results from other studies in first-episode schizophrenia or related disorders showed that baseline use of cannabis significantly increased the hazard of nonadherence and hazard of treatment discontinuationCitation25 and was significantly correlated with nonadherence during a 5-year period.Citation30 However, cannabis use was not a predictor of nonadherence when hostility, uncooperativeness, and involuntary admission were entered into the model.Citation30

Aside from past history of nonadherence, recent use of illicit drugs and recent use of alcohol were the strongest independent predictors of nonadherence in a large study of patients with schizophrenia.Citation34 Current substance abuse and current alcohol dependence were also baseline predictors of nonadherence during follow-up in another large study of patients with schizophrenia.Citation12 Use of cannabis during the acute phase was the most influential significant variable associated with nonadherence during the maintenance phase in patients with bipolar disorder; use of alcohol and substances other than cannabis during the study was significantly greater in the nonadherent group compared with the adherent group.Citation23

Cross-sectional studies

Substance abuse was among the 3 most influential variables predicting nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders and was independent of depressive symptoms and living instability.Citation53 Chewing the traditional herbal stimulant khat and use of social drugs were significantly associated with poor adherence in Ethiopian patients with schizophrenia and related disorders.Citation35,Citation39 In schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, use of alcohol and illicit substances including cannabis was significantly greater in partially adherent or nonadherent European patients relative to those who were adherent.Citation37 In US veterans with bipolar disorder, binge drinking was the third most influential variable significantly associated with poor adherence.Citation44 Similarly, alcohol dependence of patients with bipolar disorder reported by physicians in a survey was the most influential variable significantly associated with nonadherence.Citation49 In patients with SMI who had a recent history of substance abuse or addiction, lower self-efficacy for drug avoidance was among the 3 reasons included in a regression model predicting nonadherence.Citation42

Cognitive impairments

Seven studies analyzed the relationship between variables related to impaired cognition and adherence: 2 were prospective and 5 were cross-sectional.

Patients with schizophrenia who were nonadherent at 3 months exhibited significantly worse time- and event-based prospective memory at baseline relative to those who were adherent.Citation21 However, prospective memory was not a significant independent predictor of adherence in a regression model but rather a moderator of the effect of insight and psychopathology.Citation21 In patients with previously untreated first-episode schizophrenia, no relationship was found between global and domain-specific cognitive performance and adherence 6 months following admission into a specialized clinical program.Citation24

Results from a cross-sectional study of Korean patients with chronic schizophrenia reported that poor executive function was a significant predictor of nonadherence; however, other cognitive functions, such as long-term memory, perception, and attention with working memory, were not significant.Citation36 Forgetfulness was the most common reason for nonadherence self-reported by poorly adherent patients with schizophrenia and related disorders in EthiopiaCitation39 and by patients with bipolar disorder.Citation43 These results are supported by a finding from Nigeria that adherent patients took significantly smaller numbers of prescribed medications, possibly suggesting a lower burden on memory, compared with those who were nonadherent.Citation40 In contrast, in patients aged >50 years with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or MDD, a greater number of received medications and greater medication treatment complexity were correlated with better informant-rated adherence, although not with self-reported adherence or adherence estimated by pill counts.Citation52

Family/social support

Six studies assessed family and/or social support as potential reasons affecting adherence: 3 were prospective and 3 were cross-sectional. Among patients with early-episode schizophrenia, greater perceived family involvement in treatment and more positive family attitude toward medication at discharge from the hospital were significantly associated with adherence 6 months after discharge but were not included in a best-fitting regression model predicting adherence at 6 months.Citation22 Results from a randomized clinical trial comparing long-term outcomes from integrated and standard treatment interventions of patients with recent-onset schizophrenia or related disorders reported that living in families with low expressed emotions (suggesting poor attitude and feelings expressed by a relative about a mentally ill family member) at baseline was a significant long-term predictor of poor adherence.Citation28 In another prospective study, a low level of social support as rated by case managers, but not by patients, was found to be a major predictor of nonadherence in patients with first-episode psychosis.Citation26

Patients with schizophrenia in Nigeria who reported good social support had better adherence compared with those reporting poor social support, but the level of support was not an independent variable included in a best-fitting regression model predicting nonadherence.Citation40 In patients with SMI who had a recent history of substance abuse or addiction, lower social support for mental health recovery was among 3 reasons predicting nonadherence in a regression model.Citation42 However, family involvement assessed as support from significant others in a study of patients with schizophrenia in poor regions of Australia was not an independent variable in a best-fitting regression model predicting nonadherence.Citation50 In that study, poor access to a psychiatrist and experiencing side effects were identified as the most significant predictors of nonadherence.Citation50

Access to mental health care

Two cross-sectional studies assessed the association between access to a psychiatrist and adherence. In a study of US veterans with bipolar disorder receiving treatment at a large mental health facility in western Pennsylvania, limited access to a mental health specialist was among 3 independent variables most influencing poor adherence in a regression model that also included low medication beliefs (a negative attitude toward medication) and binge drinking.Citation44 A cross-sectional study of patients with schizophrenia residing in economically disadvantaged and poorly accessible regions in Australia found that difficulty accessing a psychiatrist was the most influential predictor of nonadherence in a regression model.Citation50

Social functioning

Three studies assessed the association between variables related to social functioning and adherence. A post hoc analysis of data from a prospective observational study of patients with schizophrenia reported that being socially inactive and having independent housing at baseline were predictors of nonadherence during 3 years of follow-up.Citation12 Social instability, specifically having moved in the past 30 days, was among the 3 most influential variables predicting nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders and was independent of depressive symptoms and substance abuse.Citation53 Good community functioning correlated with informant-rated adherence but not with pill counts or self-reported adherence of patients aged >50 years with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or MDD.Citation52

Depression

Three studies analyzed the relationship between depression and adherence in patients with schizophrenia or related disorders. Use of antidepressants before enrollment was among the 5 best predictors of nonadherence in a regression model that analyzed data from a large prospective study.Citation34 Having depressive symptoms, specifically feeling emotionally numb, was among 3 variables predicting nonadherence independent of social instability and substance abuse.Citation53 Having more severe depressive symptoms was among the 3 most significant variables associated with nonadherence of patients with chronic schizophrenia in Korea.Citation36

Discussion

This systematic review of modifiable reasons why patients with SMI do not take their prescribed antipsychotic medication found 11 patient-, HCP-, or family-reported factors that seem to drive adherence behavior. The reasons are often interrelated and have been linked to intentional or unintentional nonadherence. This review has focused on modifiable reasons because these can potentially be addressed with targeted interventions.

Regardless of diagnosis and stage of illness, variables that showed a significant association with intentional nonadherence in most studies were insight, attitude toward medication, and therapeutic alliance. Measures of several dimensions of insight were shown to correlate with measures of attitude toward medicationCitation46 or therapeutic alliance;Citation19 additionally, both insight and therapeutic alliance seem to predict the attitude toward medication,Citation60 which indicates that these 3 variables are closely related. More detailed analyses that examined the relationship among these variables suggested that the effect of insight and therapeutic alliance on adherence is indirect and likely mediated by attitude toward medication.Citation22,Citation27,Citation46 Therefore, attitude toward medication seems to be a key reason for intentional nonadherence and a mediator of effects of other critical variables, such as insight and therapeutic alliance. In contrast with this result, a recent systematic review assessing factors associated with nonadherence to antipsychotic treatment in bipolar disorder and schizophreniaCitation61 did not identify attitude toward medication as a risk factor.

Medication side effects may be linked to attitude toward medication by affecting both the necessity and concern dimensions. Although cross-sectional studies showed a significant association between nonadherence and side effects, prospective studies suggest a more complex relationship likely reflecting 2 competing influences: the deterring impact of side effects versus willingness of patients to accept the discomfort of side effects in exchange for medication benefit. The balance between these influences is perhaps determined by patients’ expectations of treatment and specific side effects. For example, weight gain attributed to treatment with antipsychotics may contribute to nonadherence among patients who perceive a negative effect on their body image but not among those who are indifferent to their weight status.Citation45

Among the reasons for unintentional nonadherence, substance use or abuse was the only variable consistently found to contribute, regardless of type and stage of SMI. Current abuse of alcohol and/or illicit drugsCitation12,Citation32,Citation34 and use of cannabisCitation23,Citation25 were strong independent predictors of future nonadherence. Of note, insight and attitude toward medication may not be powerful predictors of adherence for individuals with a history of substance abuse, as suggested by results from studies of patients with first-episode psychosis.Citation30,Citation32 Some patients may use recreational drugs or alcohol to self-manage symptoms of illness or to temporarily escape the stresses of a chronic health condition. Substance abuse is clearly a risk factor for poor adherence, and social and competence enhancement approaches targeting drug abuse in these individuals need to address the important issue of comorbidity. This review found that depressive symptoms may predict nonadherence for patients with schizophrenia, but the evidence is limited. Similarly, the relationship between adherence and some aspects of social functioning was assessed only in 3 studies, and the evidence regarding this complex variable is insufficient to evaluate its significance.

Lack of family/social support is another factor that may contribute to unintentional nonadherence. Positive family attitude to treatment and active family involvement in treatment of patients with schizophrenia were significantly associated with adherence; this effect may be indirect and possibly mediated by other variables, such as patient insight or attitude toward medication. Good social support for recovery from mental illness may be particularly important for adherence of patients who abuse substances, as suggested by results from a cross-sectional study that specifically examined reasons for nonadherence of patients with SMI and substance use disorder.Citation42 Likewise, access to a mental health specialist, an indicator of good health care support, may be a variable affecting adherence, particularly for patients residing in geographic areas underserved by mental health care services, but the evidence assessed in this review is limited.

Patients with SMI often exhibit cognitive impairmentsCitation62,Citation63 that may hinder regular medication taking; however, results from the selected studies are inconsistent. Specific cognitive impairments interfering with the ability to manage medication may contribute to nonadherence, but the impact likely depends on other conditions and circumstances. For example, cognitive impairment may be a substantial obstacle for adherence among patients living independently or lacking good family support but not for those living with a family member involved in planning and monitoring medication intake. In addition, some impairments, such as forgetfulness and momentary distraction, may not be easily discovered using traditional cognitive testing and, therefore, may be underestimated as reasons affecting day-to-day medication adherence.

Chronicity of SMI may be an important factor in adherence, with nonadherence at early stages of illness being influenced by reasons that differ from those associated with long-term SMI. Although a direct comparison is difficult, results from studies in first-episode psychosis provide some direction. Negative initial interaction with staff members, involuntary admission,Citation30 initial refusal to accept medication,Citation26 use of cannabis during treatment,Citation25 recent history of alcohol and drug misuse,Citation32 perception of being overweight,Citation45 and poor social support from family and friendsCitation26 may be reasons for nonadherence that are particularly potent in first-episode psychosis. Consistent with the findings of this review, a positive relationship with the treating physician has been identified as the major reason for adherence in patients with first-episode schizophrenia when compared with responses to the same questionnaire obtained from patients with multi-episode schizophrenia.Citation64

Limitations

The inherent limitation of research on adherence is that only a subset of potential reasons can be assessed in parallel in each study. For example, a large prospective observational study of patients with schizophrenia that identified prior nonadherence, substance abuse, prior treatment with antidepressants, and greater medication-related cognitive impairments as the most significant predictors of nonadherence did not collect data on measures of attitude toward medication and therapeutic alliance and assessed insight only by using 1 item on the PANSS scale.Citation34 Similarly, measures of attitude toward medication, insight, and therapeutic alliance were not included in another large prospective observational study of patients with schizophrenia that reported poor adherence at baseline, current alcohol dependence and substance abuse, independent living, and hostility at baseline as significant independent predictors of nonadherence.Citation12 Because variables that are not measured may influence not only adherence but also the effects of measured variables on adherence, such uncontrolled confounding may lead to biased results and erroneous conclusions. Differences in study design (randomized controlled trial [RCT] versus observational) could also affect the results. Although RCTs provide a carefully controlled environment that ensures that the patient takes the medication as directed, routine care is better captured by observational studies.

Another major limitation of adherence research is the lack of an objective and reliable method of adherence measurement. The currently available objective methods, such as the Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS®) bottle caps that capture pill container opening, pill counts, and pharmacy refill records, have limitations and provide only an estimate of patient adherence.Citation65 Biologic assays that detect a drug or its metabolite in bodily fluids are rarely used because of the time-consuming and costly process that requires an office visit, invasive collection techniques, and laboratory analysis. The most commonly used modalities are subjective approaches relying on patient self-report or assessment provided by the HCP or caregiverCitation66 that have low accuracy and tend to underestimate nonadherence.Citation67 Despite these well-known limitations, 53% (19/36) of studies selected for this review used a patient or HCP report as the only measure of adherence. Combining subjective measures from multiple sources (patient, HCP, and caregiver) with more objective modalities, such as pill counts or reviews of pharmacy records used in 36% (13/36) of studies, may reduce although not eliminate bias. Only 2 studies used the MEMS,Citation20,Citation48 currently considered the gold standard for objective adherence assessment. Therefore, it is likely that nonadherence was underestimated in a large portion of the studies because a majority used unreliable adherence detection methods. In addition to differences in measuring adherence, there is substantial variability in adherence definitions and categories. Because the variable can be operationalized as dichotomous, categorical, or continuous, it is difficult to compare findings across studies. Furthermore, the inherently unstable nature of adherence over time complicates its prospective assessment. Taken together, the heterogeneity of research on adherence compromises the ability to compare results across individual studies.

It is important to note that none of the studies could conclusively establish causality of the analyzed associations. Prospective studies identified in this review provide a more robust data set with multiple assessments over time and thus a higher level of evidence relative to cross-sectional studies, but the findings remain associational because of the noninterventional design used in these studies.

The 11 categories of reasons for nonadherence identified in this systematic review likely represent at least a large majority of modifiable variables that contribute to this issue in patients with SMI. However, 2 limitations should be noted. First, some modifiable reasons for nonadherence that have appeared in the literature were not identified in this review. Examples include patient inability to pay for medication,Citation68 logistic problems, and disorganized and chaotic living situation.Citation69 Second, although the search aimed to identify articles related to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and MDD, a vast majority of articles included in the review report results from studies of patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, which limit generalization of findings to the other SMIs. In addition, conclusions regarding the factors affecting nonadherence to individual antipsychotics cannot be made because of interpatient variability in treatment response and tolerability.

Conclusion

Although there are methodologic limitations, reasons for antipsychotic drug nonadherence identified by studies conducted over the past decade seem to be relatively consistent. This review identified attitude toward medication and substance abuse as reasons most consistently linked with nonadherence in patients with SMI. Attitude toward medication is a complex and multidimensional variable that is related to both insight and therapeutic alliance. Substance abuse can serve as a relatively simple indicator of risk for nonadherence, and prevention programs targeting drug abuse should also focus on improving adherence. Although a negative attitude toward medication and use of substances should be a red flag for clinicians in identifying individuals at high risk for nonadherence, identifying the unique needs of each patient is a necessary step in designing appropriate individual intervention strategies to improve medication adherence.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by ODH, Inc., Princeton, NJ. Writing and editorial assistance was provided by C4 MedSolutions, LLC (Yardley, PA), a CHC Group company, and funded by ODH, Inc. At the time of the literature search and analysis Ainslie Hatch and John Docherty were employees of Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc. and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. and are both currently employed by ODH, Inc.

Disclosure

Dawn I Velligan has received research support from Amgen and Otsuka; has been a consultant for Amgen, Forum, Otsuka, and Reckitt Benckiser; and has been a member of speaker bureaus for Janssen and Otsuka. Martha Sajatovic has received research support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Janssen, Merck, National Institutes of Health, Ortho-McNeil-Janssen, Pfizer, Reinberger Foundation, Reuter Foundation, and the Woodruff Foundation; has been a consultant for Bracket, Neurocrine, Otsuka, Pfizer, Prophase, and Sunovion; has received royalties from Johns Hopkins University Press, Lexicomp, Oxford University Press, Springer Press, and UpToDate; and has participated CME activities for the following organizations: American Physician Institute, CMEology, and MCM Education. Ainslie Hatch and John P Docherty are employees of ODH, Inc. Pavel Kramata was employed by C4 MedSolutions LLC at the time the research was conducted.

References

- LeuchtSTardyMKomossaKAntipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysisLancet201237998312063207122560607

- FurukawaTALevineSZTanakaSInitial severity of schizophrenia and efficacy of antipsychotics: participant-level meta-analysis of 6 placebo-controlled studiesJAMA Psychiatry2015721142125372935

- PerlisRHWelgeJAVornikLAHirschfeldRMKeckPEJrAtypical antipsychotics in the treatment of mania: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trialsJ Clin Psychiatry200667450951616669715

- NelsonJCPapakostasGIAtypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trialsAm J Psychiatry2009166998099119687129

- SpielmansGIBermanMILinardatosERosenlichtNZPerryATsaiACAdjunctive atypical antipsychotic treatment for major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of depression, quality of life, and safety outcomesPLoS Med2013103e100140323554581

- ThaseMEYouakimJMSkubanAEfficacy and safety of adjunctive brexpiprazole 2 mg in major depressive disorder: a phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled study in patients with inadequate response to antidepressantsJ Clin Psychiatry20157691224123126301701

- LacroJPDunnLBDolderCRLeckbandSGJesteDVPrevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literatureJ Clin Psychiatry2002631089290912416599

- SajatovicMValensteinMBlowFCGanoczyDIgnacioRVTreatment adherence with antipsychotic medications in bipolar disorderBipolar Disord20068323224116696824

- ValensteinMGanoczyDMcCarthyJFMyra KimHLeeTABlowFCAntipsychotic adherence over time among patients receiving treatment for schizophrenia: a retrospective reviewJ Clin Psychiatry200667101542155017107245

- WeidenPJKozmaCGroggALocklearJPartial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophreniaPsychiatr Serv200455888689115292538

- Ascher-SvanumHFariesDEZhuBErnstFRSwartzMSSwansonJWMedication adherence and long-term functional outcomes in the treatment of schizophrenia in usual careJ Clin Psychiatry200667345346016649833

- NovickDHaroJMSuarezDPerezVDittmannRWHaddadPMPredictors and clinical consequences of non-adherence with antipsychotic medication in the outpatient treatment of schizophreniaPsychiatry Res20101762–310911320185182

- HongJReedCNovickDHaroJMAguadoJClinical and economic consequences of medication non-adherence in the treatment of patients with a manic/mixed episode of bipolar disorder: results from the European Mania in Bipolar Longitudinal Evaluation of Medication (EMBLEM) studyPsychiatry Res2011190111011421571375

- VelliganDIWeidenPJSajatovicMThe expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illnessJ Clin Psychiatry200970Suppl 4146 quiz 47–4819686636

- SajatovicMLevinJTatsuokaCSix-month outcomes of customized adherence enhancement (CAE) therapy in bipolar disorderBipolar Disord201214329130022548902

- LiberatiAAltmanDGTetzlaffJThe PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health-care interventions: explanation and elaborationBMJ2009339b270019622552

- HaddadPMBrainCScottJNonadherence with antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: challenges and management strategiesPatient Relat Outcome Meas20145436225061342

- SendtKVTracyDKBhattacharyyaSA systematic review of factors influencing adherence to antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia-spectrum disordersPsychiatry Res20152251–2143025466227

- NovickDMontgomeryWTreuerTAguadoJKraemerSHaroJMRelationship of insight with medication adherence and the impact on outcomes in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: results from a 1-year European outpatient observational studyBMC Psychiatry20151518926239486

- BrainCAllerbyKSamebyBDrug attitude and other predictors of medication adherence in schizophrenia: 12 months of electronic monitoring (MEMS((R))) in the Swedish COAST-studyEur Neuropsychopharmacol201323121754176224091164

- LamJWLuiSSWangYChanRCCheungEFProspective memory predicts medication management ability and correlates with non-adherence to medications in individuals with clinically stable schizophreniaSchizophr Res20131472–329330023631929

- Baloush-KleinmanVLevineSZRoeDShnittDWeizmanAPoyurovskyMAdherence to antipsychotic drug treatment in early-episode schizophrenia: a six-month naturalistic follow-up studySchizophr Res20111301–317618121636254

- Gonzalez-PintoAReedCNovickDBertschJHaroJMAssessment of medication adherence in a cohort of patients with bipolar disorderPharmacopsychiatry201043726327020842617

- LepageMBodnarMJooberRMallaAIs there an association between neurocognitive performance and medication adherence in first episode psychosis?Early Interv Psychiatry20104218919520536976

- MillerRReamGMcCormackJGunduz-BruceHSevySRobinsonDA prospective study of cannabis use as a risk factor for non-adherence and treatment dropout in first-episode schizophreniaSchizophr Res20091132–313814419481424

- RabinovitchMBechard-EvansLSchmitzNJooberRMallaAEarly predictors of nonadherence to antipsychotic therapy in first-episode psychosisCan J Psychiatry2009541283519175977

- MohamedSRosenheckRMcEvoyJSwartzMStroupSLiebermanJACross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between insight and attitudes toward medication and clinical outcomes in chronic schizophreniaSchizophr Bull200935233634618586692

- MorkenGGraweRWWidenJHEffects of integrated treatment on antipsychotic medication adherence in a randomized trial in recent-onset schizophreniaJ Clin Psychiatry200768456657117474812

- Liu-SeifertHAdamsDHAscher-SvanumHFariesDEKinonBJPatient perception of medication benefit and early treatment discontinuation in a 1-year study of patients with schizophreniaPatient Prefer Adherence2007191719956443

- de HaanLvan AmelsvoortTDingemansPLinszenDRisk factors for medication non-adherence in patients with first episode schizophrenia and related disorders; a prospective five year follow-upPharmacopsychiatry200740626426818030650

- McEvoyJPJohnsonJPerkinsDInsight in first-episode psychosisPsychol Med200636101385139316740175

- KamaliMKellyBDClarkeMA prospective evaluation of adherence to medication in first episode schizophreniaEur Psychiatry2006211293316460918

- YamadaKWatanabeKNemotoNPrediction of medication noncompliance in outpatients with schizophrenia: 2-year follow-up studyPsychiatry Res20061411616916318875

- Ascher-SvanumHZhuBFariesDLacroJPDolderCRA prospective study of risk factors for nonadherence with antipsychotic medication in the treatment of schizophreniaJ Clin Psychiatry20066771114112316889456

- EtichaTTekluAAliDSolomonGAlemayehuAFactors associated with medication adherence among patients with schizophrenia in Mekelle, Northern EthiopiaPLoS One2015103e012056025816353

- NaEYimSJLeeJNRelationships among medication adherence, insight, and neurocognition in chronic schizophreniaPsychiatry Clin Neurosci201569529830425600955

- JonsdottirHOpjordsmoenSBirkenaesABPredictors of medication adherence in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorderActa Psychiatr Scand20131271233322900964

- DibonaventuraMGabrielSDupclayLGuptaSKimEA patient perspective of the impact of medication side effects on adherence: results of a cross-sectional nationwide survey of patients with schizophreniaBMC Psychiatry2012122022433036

- AleneMWieseMDAngamoMTBajorekBVYesufEAWabeNTAdherence to medication for the treatment of psychosis: rates and risk factors in an Ethiopian populationBMC Clin Pharmacol2012121022709356

- AdelufosiAOAdebowaleTOAbayomiOMosanyaJTMedication adherence and quality of life among Nigerian outpatients with schizophreniaGen Hosp Psychiatry2012341727922036736

- McCabeRBullenkampJHanssonLThe therapeutic relationship and adherence to antipsychotic medication in schizophreniaPLoS One201274e3608022558336

- MaguraSRosenblumAFongCFactors associated with medication adherence among psychiatric outpatients at substance abuse riskOpen Addict J20114586423264842

- SajatovicMLevinJFuentes-CasianoECassidyKATatsuokaCJenkinsJHIllness experience and reasons for nonadherence among individuals with bipolar disorder who are poorly adherent with medicationCompr Psychiatry201152328028721497222

- ZeberJEMillerALCopelandLAMedication adherence, ethnicity, and the influence of multiple psychosocial and financial barriersAdm Policy Ment Health2011382869520549327

- WongMMChenEYLuiSSTsoSMedication adherence and subjective weight perception in patients with first-episode psychotic disorderClin Schizophr Relat Psychoses20115313514121983497

- BeckEMCaveltiMKvrgicSKleimBVauthRAre we addressing the ‘right stuff’ to enhance adherence in schizophrenia? Understanding the role of insight and attitudes towards medicationSchizophr Res20111321424921820875

- DassaDBoyerLBenoitMBourcetSRaymondetPBottaiTFactors associated with medication non-adherence in patients suffering from schizophrenia: a cross-sectional study in a universal coverage health-care systemAust N Z J Psychiatry2010441092192820932206

- AcostaFJBoschESarmientoGJuanesNCaballero-HidalgoAMayansTEvaluation of noncompliance in schizophrenia patients using electronic monitoring (MEMS) and its relationship to sociodemographic, clinical and psychopathological variablesSchizophr Res20091072–321321718849150

- BaldessariniRJPerryRPikeJFactors associated with treatment nonadherence among US bipolar disorder patientsHum Psychopharmacol20082329510518058849

- McCannTVBoardmanGClarkELuSRisk profiles for non-adherence to antipsychotic medicationsJ Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs200815862262918803735

- Rummel-KlugeCSchusterTPetersSKisslingWPartial compliance with antipsychotic medication is common in patients with schizophreniaAust N Z J Psychiatry200842538238818473256

- PrattSIMueserKTDriscollMWolfeRBartelsSJMedication nonadherence in older people with serious mental illness: prevalence and correlatesPsychiatr Rehabil J200629429931016689041

- ElbogenEBSwansonJWSwartzMSVan DornRMedication nonadherence and substance abuse in psychotic disorders: impact of depressive symptoms and social stabilityJ Nerv Ment Dis20051931067367916208163

- JonsdottirHOpjordsmoenSBirkenaesABPredictors of medication adherence in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorderActa Psychiatr Scand20131271233322900964

- Rummel-KlugeCSchusterTPetersSKisslingWPartial compliance with antipsychotic medication is common in patients with schizophreniaAust N Z J Psychiatry200842538238818473256

- WeidenPRapkinBMottTRating of medication influences (ROMI) scale in schizophreniaSchizophr Bull19942022973107916162

- BirchwoodMSmithJDruryVHealyJMacmillanFSladeMA self-report Insight Scale for psychosis: reliability, validity and sensitivity to changeActa Psychiatr Scand199489162677908156

- HoganTPAwadAGEastwoodRA self-report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenics: reliability and discriminative validityPsychol Med19831311771836133297

- SwitajPWciorkaJSmolarska-SwitajJGrygielPExtent and predictors of stigma experienced by patients with schizophreniaEur Psychiatry200924851352019699063

- DayJCBentallRPRobertsCAttitudes toward antipsychotic medication: the impact of clinical variables and relationships with health professionalsArch Gen Psychiatry200562771772415997012

- GarciaSMartinez-CengotitabengoaMLopez-ZurbanoSAdherence to antipsychotic medication in bipolar disorder and schizophrenic patients: a systematic reviewJ Clin Psychopharmacol201636435537127307187

- VohringerPABarroilhetSAAmerioACognitive impairment in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: a systematic reviewFront Psychiatry201348723964248

- BoraEHarrisonBJYucelMPantelisCCognitive impairment in euthymic major depressive disorder: a meta-analysisPsychol Med201343102017202623098294

- SapraMWeidenPJSchoolerNRSunakawa-McMillanAUzenoffSBurkholderPReasons for adherence and nonadherence: a pilot study comparing first- and multi-episode schizophrenia patientsClin Schizophr Relat Psychoses20147419920623428784

- SajatovicMVelliganDIWeidenPJValensteinMAOgedegbeGMeasurement of psychiatric treatment adherenceJ Psychosom Res201069659159921109048

- VelliganDILamYWGlahnDCDefining and assessing adherence to oral antipsychotics: a review of the literatureSchizophr Bull200632472474216707778

- ByerlyMJThompsonACarmodyTValidity of electronically monitored medication adherence and conventional adherence measures in schizophreniaPsychiatr Serv200758684484717535946

- ZeberJEGrazierKLValensteinMBlowFCLantzPMEffect of a medication copayment increase in veterans with schizophreniaAm J Manag Care2007136 Pt 233534617567234

- VelliganDILamFEreshefskyLMillerALPsychopharmacology: Perspectives on medication adherence and atypical antipsychotic medicationsPsychiatr Serv200354566566712719495