Abstract

Background

Medicine-related burden is an increasingly recognized concept, stemming from the rising tide of polypharmacy, which may impact on patient behaviors, including nonadherence. No instruments currently exist which specifically measure medicine-related burden. The Living with Medicines Questionnaire (LMQ) was developed for this purpose.

Objective

This study validated the LMQ in a sample of adults using regular prescription medicines in the UK.

Methods

Questionnaires were distributed in community pharmacies and public places in southeast England or online through UK health websites and social media. A total of 1,177 were returned: 507 (43.1%) from pharmacy distribution and 670 (56.9%) online. Construct validity was assessed by principal components analysis and item reduction undertaken on the original 60-item pool. Known-groups analysis assessed differences in mean total scores between participants using different numbers of medicines and between those who did or did not require assistance with medicine use. Internal consistency was assessed by Cronbach’s alpha. Free-text comments were analyzed thematically to substantiate underlying dimensions.

Results

A 42-item, eight-factor structure comprising intercorrelated dimensions (patient–doctor relationships and communication about medicines, patient–pharmacist communication about medicines, interferences with daily life, practical difficulties, effectiveness, acceptance of medicine use, autonomy/control over medicines and concerns about medicine use) was derived, which explained 57.4% of the total variation. Six of the eight subscales had acceptable internal consistency (α>0.7). More positive experiences were observed among patients using eight or fewer medicines compared to nine or more, and those independent with managing/using their medicines versus those requiring assistance. Free-text comments, provided by almost a third of the respondents, supported the domains identified.

Conclusion

The resultant LMQ-2 is a valid and reliable multidimensional measure of prescription medicine use experiences, which covers more diverse domains than existing questionnaires. However, further validation work is necessary.

Introduction

Polypharmacy is increasing worldwide,Citation1–Citation3 driven by disease-specific clinical guidelines and specialist care, and has been recognized by policy makers in England as a problem to be addressed.Citation4,Citation5 This increasing tide of prescribing, frequently involving prophylactic drugs for secondary prevention, is clearly becoming burdensome to some patients.Citation6–Citation8 The need to use long-term medicines engenders a mix of emotions, frequently combining gratitude for the potential benefits with anxiety about adverse effects and general skepticism about net gain.Citation9 Numerous studies in different countries show that most patients would prefer not to take medicines, particularly those with chronic conditions, that some patients are resistant toward using medicinesCitation10 and that there is a desire among some to stop some or all of their medicines.Citation11 However, these perceptions and views may not always be taken into account during consultations about treatment, or incorporated into research studies, despite the increasing emphasis placed on patient perspectives of health outcomes both in practice and in research.

Recent policy documents in the UK seek to promote strategies for optimizing the growing problem of polypharmacy in individual patients,Citation4,Citation5,Citation12 but in order to determine which patients are most likely to benefit from interventions and to evaluate the interventions themselves, a patient-centered measure of experiences of multiple medicine use is needed.

A number of instruments exist which seek to measure satisfaction with medicinesCitation13,Citation14 and the overall impact of using medicines on quality of life.Citation15 The long-term use of medicines is, however, multidimensional and complex; any individual can experience both positive and negative aspects of medicine use.Citation16–Citation18 No existing instrument covers all issues that patients describe in their varied experiences of using medicines.Citation19 A recently developed generic measure of treatment burden, defined as “the impact of health care on patients’ functioning and well-being”, exists,Citation20 which includes, but is not specific to, the burden of prescription medicine use. A number of disease-specific measures of treatment burden mostly assess the workload of self-managing diabetes and are not applicable to other long-term conditions.Citation21 Medicine-related burden is a relatively new concept, which a recent metasynthesis of qualitative studies suggests impacts on behaviors, including nonadherence.Citation18 In addition to side effects and potential adverse events, medicine burden includes practical difficulties (such as opening packaging), challenges with managing complex regimes, psychosocial issues, particularly social stigma, disruptions to daily living and health system burden associated with regular medicine use, the latter including both patient–provider communication and information burden.Citation18,Citation22 Hence, any instrument purporting to measure medicine burden must cover these issues. Medicine characteristics and prescribing regimens may all affect burden, for example, number of medicines, formulations, route of administration, complex dosage regimens and generic brand switching.Citation18

The Living with Medicines Questionnaire (LMQ; Supplementary material) was developed for the specific purpose of measuring overall medicines burden.Citation22 The instrument was based on the findings from interviews with 21 patients of different ages who were taking a diverse range of long-term multiple medicines,Citation23 and covered the range of issues outlined above. Both initial item generation and content validation involved patients, unlike many instruments purporting to represent patient views.Citation19 Preliminary testing of the LMQ involved patients taking long-term medicines recruited from an English primary care setting.Citation22 This instrument included 60 statements (items), accompanied by a five-point Likert-type scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) plus a free-text open question. Results suggested that a larger sample was required to enable further psychometric testing and to reduce the number of items into a more manageable instrument. We describe here the results of psychometric testing and further development of this instrument.

Methods

Study population

Members of the general public were targeted for this study, as the proportion of people using long-term medicines in England is high (>50%)Citation1 and it enabled us to reach a diverse population. Ethics approval was granted by Medway School of Pharmacy Research Ethics Committee.

The inclusion criteria were adults, using regular prescription medicines and living in the UK. All potential participants were provided with information about the study’s purpose and informed that consent was implied by completion and return of the questionnaire. Those interested were required to answer screening questions to ensure they met the inclusion criteria before completing the instrument.

Questionnaire distribution

A mixed-methods approach was used to maximize both response rates and diversity of demographic characteristics. The two main methods of distribution were 1) paper questionnaires distributed to both the general public using street intercept and to community pharmacy users in southeast England and 2) an online survey available to the UK general public recruited through social media and health websites. Street surveys yield wide, representative, sociodemographic profiles, in terms of age, education or employment and are also a cost-effective distribution method for paper surveys,Citation24,Citation25 while distribution to community pharmacy users increases the likelihood of reaching the people using long-term medicines. The online survey was utilized to reach people from a wider geographic distribution, including the housebound, but is more likely to reach those with higher education and socioeconomic status.

Recipients of paper questionnaires were given freepost envelopes for return. Online survey responses were downloaded from the provider website (Qualtrics®).

Data analysis

Data were managed and analyzed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 22). Two databases were set up to handle paper and online surveys separately, then checked for errors and merged for analysis. Any significant differences in participant characteristics were examined using chi-squared tests. The 60-item pool had 34 positively phrased and 26 negatively phrased statements. Reverse scoring enabled uniformity in the direction of responses, such that higher scores depicted negative experiences with medicine use.

Principal components analysis (PCA)

The correlation matrix was examined for item intercorrelations, and Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (acceptable values >0.6) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (acceptable if P-value <0.05) were computed to ensure the data were suitable for factor analysis.Citation26 PCA was conducted on the combined dataset using oblique rotation techniques (promax), assuming intercorrelations among underlying components (factors), to ascertain the dimensional structure of the instrument. Scree plots (of eigenvalues and their associated number of components), and Kaiser’s rule (retain only factors with eigenvalue >1) were used to assess questionnaire dimensionality. In addition, parallel analysis with Monte Carlo PCA was used to confirm the number of appropriate factors.Citation27 We then reviewed the remaining items for potential floor or ceiling effects (ie, items with >50% of answers concentrated in the first or last answer category) and examined item skewness and kurtosis (acceptable values <1.0).

Reliability analysis

Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha (acceptable values >0.7), and changes in alpha following deletion of individual items from subscales were used to further inform decisions on item reduction/retention.

Known-groups validity

Known-groups analysis compared mean total LMQ-2 scores (for the 42-item version) between subsets of participants predicted to experience different degrees of burden, relating to the numbers of medicines used and whether assistance with managing medicines was required. Independent sample t-tests and one-way analysis of variance, involving only those respondents who completed all the LMQ items, were used for this analysis as LMQ-2 scores were normally distributed.

Responses to open question

The free-text comments box allowed respondents to add any other views about how medicines affected their day-to-day life in order to determine whether any outstanding major issues arose not covered by the instrument. Responses were analyzed thematically using the eight themes identified in the patient interviews, from which the original item pool was derivedCitation23 as an additional measure of the validity of the instrument.

Results

A total of 507 responses were obtained using paper questionnaires (45.6% of all those meeting the inclusion criteria), with more than half the respondents having been recruited from community pharmacies (60.5%, n=307). A total of 670 participants completed the online survey (68.4% of those accessing the survey link) through health websites (38.2%, n=374) and social media (30.2%, n=296). Overall, 544 questionnaires were fully completed on the original 60-item pool, and the overall item-level response rates were over 90%. Most items had skewness and kurtosis statistics <1.0, suggesting a tendency to univariate normality of the dataset. Raw mean scores on all items ranged from 2.13±1.02 to 4.60±0.71. Only 5 of 60 items had skewness and kurtosis statistics >1 in absolute value, and one item had 68.5% of responses at the ceiling.

Participant characteristics

More females completed both paper (62.1%) and online (81.6%) surveys than males (P<0.001), with the overall age of participants ranging from 18 to 90 years (). Younger respondents (<65 years) and those with college/further education mostly completed the online survey, whereas more people aged 65 and above returned the paper survey (P<0.001). Overall, most participants (80.4%, n=992) used up to and including eight prescription medicines, 113 (9.7%) needed assistance with using their medicines and 326 (27.9%) paid for their National Health Service prescription medicines.

Table 1 Characteristics of participants completing the survey

Results of the PCA

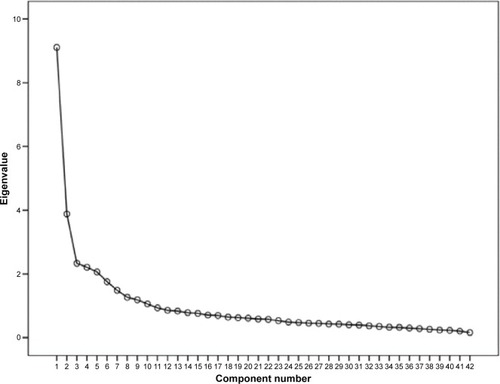

A total of 544 fully completed responses (listwise deletion of missing data) were subjected to PCA. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin statistic (0.888) was satisfactory (>0.6) and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (chi-square =9,788.903, degrees of freedom =861, P<0.001); thus, the data met the necessary criteria for factor analysis. Moreover, interitem correlation coefficients showed no evidence of multicollinearity (r<0.8),Citation28 which also encouraged PCA. The initial solution resolved into 14 components with eigenvalues >1.0, explaining 61.1% of the total variation. Inspection of the scree plot revealed two breaks at the fifth and ninth components ().

Figure 1 Scree plot of the number of components (factors) in the Living with Medicines Questionnaire, showing two breaks at components 5 and 9, suggesting a multidimensional factor solution.

Parallel analysis (Monte Carlo PCA) confirmed eight components with observed eigenvalues exceeding the criterion values (). PCA was re-run and the number of components fixed to eight. The resulting eight-factor solution explained 57.4% of the total variation and was conceptually interpretable ().

Table 2 Comparison of observed and criterion eigenvalues from parallel analysis

Table 3 Pattern matrix of the 42-item, eight-factor structure of the LMQ-2

Item reduction and factor structure

Items with factor loadings <0.4 and/or cross loadings of ≥0.32 on at least two factors were deleted, based upon professional judgment that they did not fit well in underlying domains. This resulted in removal of 18 items (n=18) from the original item pool, leaving 42 items. Five items with ceiling effects were retained as their factor loadings exceeded the minimum threshold for item retention (≥0.4), and were also judged as conceptually relevant.

shows the 42-item factor structure. Emerging factors were interpreted as: patient–doctor relationships and communication about medicines (9 items), interferences with daily life (8 items), practicalities (7 items), effectiveness (4 items), patient–pharmacist communication about medicines (3 items), acceptance of medicine use (4 items), autonomy/control over medicine use (4 items) and concerns about potential harm (3 items). Most subscales have acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha range, 0.592–0.887).

All factor intercorrelations were <0.8 (range 0.099–0.711), suggesting minimal redundancy among instrument subscales, and thus possible discriminant validity.Citation29 The strongest correlation was between perceived effectiveness and patient–doctor relationships and communication about medicines (r=0.711, P<0.001; ). Autonomy was negatively correlated with all other subscales, in particular, acceptance of medicine use ().

Table 4 Intercorrelations among the LMQ-2 subscales

Known-groups validity

As hypothesized, the instrument was able to distinguish between participants using different numbers of medicines and between those who did or did not require assistance with medicine use. The mean LMQ-2 total score increased with the number of medicines used, and the medicine burden score for those requiring assistance was higher than for those who did not ().

Table 5 Known-groups validity of the LMQ-2

Free-text comments

A total of 421 different comments were received, almost all of which supported the content domains. In particular, there were 76 comments describing the impact of using medicines, 71 describing medicine-related disruption to daily activities, 65 describing the impact of adverse effects on daily activities, personal life and socialization, 61 relating to efficacy or its lack and concerns about dependence on medicines for symptom relief, performance of daily activities and prolonging life, 79 covering practical issues including desire for more suitable packaging and labeling, and information and 58 describing relationships with health professionals.

Discussion

This study reports the validation of the LMQ, a generic multidimensional questionnaire designed to encompass issues experienced by patients using long-term medicines, into a potentially useful instrument, the LMQ-2. The original LMQ was shown to cover more domains than most other instruments purporting to describe patient experiences of medicine use.Citation19 The instrument covers eight interrelated, yet distinct, dimensions of the medicine use experience: perceptions about effectiveness, concerns about medicine use, patient–provider relationships and communication about medicines, practical difficulties, interferences with daily life, autonomy/control over medicine and acceptance of medicine use, which have been cited by users of long-term medicines as burdensome.Citation18 These dimensions match well to both the domains identified from qualitative research on which the instrument was originally based and with subsequent literature.Citation18,Citation19 Additional comments added by questionnaire respondents also support these domains. We believe they all relate to an overarching construct of medicine burden, for which no measure currently exists.

Perceptions of efficacy and concerns about the negative effects of medicines are widely reported in the literature, with most patients weighing benefits from medicines against any associated burden, perhaps enduring inconveniences associated with their use while reluctantly accepting the need for treatment.Citation18,Citation30,Citation31 Patients’ perceptions concerning the desired therapeutic outcome influence both attitudes and behaviors toward medicine.Citation32,Citation33 Concerns about potential harm from side effects, long-term use and/or dependency are common.Citation10 Relationships with health professionals supplying medicines and information sharing may influence both commitment to taking medicines and perceptions of effectiveness,Citation31 with poor relationships and communication becoming burdensome to some individuals due to consultation styles, amount of information provided, conflicting information and lack of continuity of care.Citation34,Citation35 Observational research shows that overall treatment burden may be compounded by patients’ experiences of medicine use being neglected during consultations.Citation36 Practical difficulties with the long-term use of medicines have been documented as burdensome,Citation37–Citation39 while the burden of managing medicine routines has been reported as demanding of both time and resources.Citation8,Citation18 There is also evidence that many patients manipulate their medicine regimens, especially when they experience unbearable burden, perceive their medicines as inappropriate or are dissatisfied with their medicine.Citation33,Citation40–Citation42 Conversely, regimens which are inconvenient may lead to perceived lack of control or autonomy. The autonomy subscale was highly negatively correlated with acceptance of medicine use, suggesting that such acceptance may be associated with perceived inability to modify regimens. This, together with experiences of adverse effects, may add to the overall burden through interfering with daily activities.Citation18 Indeed, our data support this, with the domain of practicalities being positively correlated with interference, but also negatively correlated with autonomy. Negative correlations were also found between autonomy and communication with both doctors and pharmacists, which may suggest a reluctance to go against the advice/directions of health care professionals.

The eight subscales of the LMQ-2 are valid and reliable. The generic nature of this questionnaire contributes to its potential usefulness in identifying a wide range of issues arising from medicine use either in single conditions or in patients with multimorbidity. Preliminary evidence of the measure’s discriminant validity is promising, with the data showing that using a higher number of medicines and needing assistance with medicines were significantly associated with more medicine burden.

Strengths, limitations and future work

The LMQ looks promising as a patient-reported measure of the burden of using long-term medicines. Item-level response rates were generally high, potentially indicating interest in the medicine-related issues covered in the questionnaire. Unlike many instruments reported in the literature, the development and validation of the LMQ were founded on patient-generated data from representative patient populations.

Elimination of poorly performing items, using psychometrically sound criteria and an adequate sample size recruited from demographically diverse settings, resulted in a revised instrument, the LMQ-2. However, the item reduction process may have led to loss of potentially important items. Side effects did not emerge as a separate domain, instead merging with concerns about potential harm, but generated a significant number of free-text comments. No significant ceiling effects were apparent, in contrast to measures of treatment satisfaction.Citation13 The reliability of the LMQ-2 sub-scales may be strengthened by use of both negatively and positively phrased statements and the intermixed ordering of items across different content domains. Methodological studies suggest that grouping questionnaire items into their hypothetical domains, a common occurrence in existing medicine-related measures, may artificially inflate internal consistency.Citation43 Potential obsequiousness bias, a common methodological problem with self-report measures, was minimized by the use of different self-report methods (paper and online), encouraging completion outside of standard health facilities, in diverse public settings.

Further development work is necessary to assess criterion-related validity by comparison with existing measures of the medicine use experience. Our samples were insufficiently large to assess whether the different distribution methods resulted in any differences in the instrument’s psychometric properties. Moreover, confirmatory factor analysis was not undertaken. Thus, further work is required with larger sample sizes to enable these analyses. Cross-cultural adaptations may be needed to support the instrument’s usability in other populations. Future studies may also involve adaptations of the LMQ (or its subscales) for use in specific disease conditions or patient populations.

Conclusion

The LMQ-2 is a valid and reliable multidimensional measure of adult patients’ experiences of prescription medicine use. Although further work on the instrument is desirable, the findings reported here are promising and suggest the instrument may be useful in measuring medicine-related burden, currently a neglected aspect of the assessment of health care interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants, and patient organizations, health websites, community pharmacies and managers of public areas in southeast England that permitted survey distribution. They also thank Mairead O’Grady, Chandra Vaghji, Ruby Rubasayone and Temi Ojikutu for their support with data collection.

This work was supported by the Medway School of Pharmacy, The Universities of Kent and Greenwich as part of a PhD program, and by an award from the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission (CSC), funded by the UK government.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- DuerdenMAveryTPayneRPolypharmacy and Medicines Optimisation – Making It Safe and SoundLondonThe King’s Fund2013 Available from: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/polypharmacy-and-medicines-optimisation-kingsfund-nov13.pdfAccessed October 4, 2016

- GuthrieBMakubateBHernandez-SantiagoVDreischulteTThe rising tide of polypharmacy and potentially serious drug interactions 1995–2010: repeated cross sectional analysis of dispensed prescribing in one regionBMC Med2015137425889849

- HovstadiusBHovstadiusKÅstrandBPeterssonGIncreasing polypharmacy – an individual-based study of the Swedish population 2005–2008BMC Clin Pharmacol2010101621122160

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)Medicines Optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes2015 Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5/resources/medicines-optimisation-the-safe-and-effective-use-of-medicines-to-enable-the-best-possible-outcomes-51041805253Accessed September 3, 2016

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS)Medicines optimisation: helping patients to make the most of medicinesGood practice guidance for healthcare professionals in EnglandLondon2013 Available from: https://www.rpharms.com/promoting-pharmacy-pdfs/helping-patients-make-the-most-of-their-medicines.pdfAccessed October 1, 2016

- MayCMontoriVMMairFSWe need minimally disruptive medicineBMJ2009339b280319671932

- MoenJBohmATilleniusTAntonovKNilssonJLRingL“I don’t know how many of these [medicines] are necessary.” – a focus group study among elderly users of multiple medicinesPatient Educ Couns200974213514118845412

- SavAKendallEMcMillanSS‘You say treatment, I say hard work’: treatment burden among people with chronic illness and their carers in AustraliaHealth Soc Care Community201321666567423701664

- NørresletMBissellPTraulsenJMFrom consumerism to active dependence: patterns of medicines use and treatment decisions among patients with atopic dermatitisHealth (London)20101419110620051432

- PoundPBrittenNMorganMResisting medicines: a synthesis of qualitative studies of medicine takingSoc Sci Med200561113315515847968

- ReeveEWieseMDHendrixIRobertsMSShakibSPeople’s attitudes, beliefs, and experiences regarding polypharmacy and willingness to deprescribeJ Am Geriatr Soc20136191508151424028356

- Scottish Government Model of Care Polypharmacy Working GroupPolypharmacy Guidance2nd edEdinburghScottish Government32015 Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/polypharmacy_guidance.pdfAccessed October 13, 2016

- AtkinsonMJKumarRCappelleriJCHassSLHierarchical construct validity of the treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication (TSQM version II) among outpatient pharmacy consumersValue Health20058Suppl 1S9S2416336491

- RuizMAPardoARejasJSotoJVillasanteFArangurenJLDevelopment and validation of the “Treatment satisfaction with medicines questionnaire” (SATMED-Q)Value Health200811591392618494753

- SakthongPSuksangaPSakulbumrungsilRWinit-WatjanaWDevelopment of patient-reported outcomes measure of pharmaceutical therapy for quality of life (PROMPT-QoL): a novel instrument for medication managementRes Social Adm Pharm201511331533825453539

- SavAKingMAWhittyJABurden of treatment for chronic illness: a concept analysis and review of the literatureHealth Expect2013183113

- MurawskiMMBentleyJPPharmaceutical therapy-related quality of life: conceptual developmentJ Soc Adm Pharm2001181214

- MohammedMAMolesRJChenTFMedication-related burden and patients’ lived experience with medicine: a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studiesBMJ Open201662e010035

- KatusiimeBCorlettSReeveJKrskaJMeasuring medicine-related experiences from a patient’s perspective: a systematic reviewPatient Relat Outcome Meas2016715717127785116

- TranVTMontoriVMEtonDTBaruchDFalissardBRavaudPDevelopment and description of measurement properties of an instrument to assess treatment burden among patients with multiple chronic conditionsBMC Med2012106822762722

- EtonDTElraiyahTAYostKJA systematic review of patient-reported measures of burden of treatment in three chronic diseasesPatient Relat Outcome Meas2013472023833553

- KrskaJMorecroftCWRowePHPooleHMeasuring the impact of long-term medicines use from the patient perspectiveInt J Clin Pharm201436467567824997013

- KrskaJMorecroftCWPooleHRowePHIssues potentially affecting quality of life arising from long-term medicines use: a qualitative studyInt J Clin Pharm20133561161116923990332

- MillerKWWilderLBStillmanFABeckerDMThe feasibility of a street-intercept survey method in an African-American communityAm J Public Health19978746556589146448

- SaramuneeKMackridgeAPhillips-HowardPRichardsJSuttajitSKrskaJMethodological and economic evaluations of seven survey modes applied to health service researchJ Pharm Health Serv Res2015714352

- PallantJSPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis using IBM SPSS5th edMaidenheadMcGraw-Hill2013

- WatkinsMWDetermining parallel analysis criteriaJ Mod App Stat Meth200652344346

- KahnJHFactor analysis in counseling psychology research, training, and practice principles, advances, and applicationsCouns Psychol2006345684718

- FieldADiscovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics: and sex and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll4th edLondonSage2013

- BajcarJTask analysis of patients’ medication-taking practice and the role of making sense: a grounded theory studyRes Social Adm Pharm200621598217138501

- ChenCHWuJRYenMChenZCA model of medication-taking behavior in elderly individuals with chronic diseaseJ Cardiovasc Nurs200722535936517724416

- WilliamsAFManiasEWalkerRAdherence to multiple, prescribed medications in diabetic kidney disease: a qualitative study of consumers’ and health professionals’ perspectivesInt J Nurs Stud200845121742175618701103

- LemppHHofmannDHatchSLScottDLPatients’ views about treatment with combination therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: a comparative qualitative studyBMC Musculoskel Disord201213200

- MillerSMMonitoring and blunting: validation of a questionnaire to assess styles of information seeking under threatJ Pers Soc Psychol19875223453533559895

- CarpenterDMDeVellisRFFisherEBDeVellisBMHoganSLJordanJMThe effect of conflicting medication information and physician support on medication adherence for chronically ill patientsPatient Educ Couns201081216917620044230

- BohlenKScovilleEShippeeNDMayCRMontoriVMOverwhelmed patients a videographic analysis of how patients with type 2 diabetes and clinicians articulate and address treatment burden during clinical encountersDiabetes Care2012351474922100962

- EtonDTRamalho de OliveiraDEggintonJSBuilding a measurement framework of burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditions: a qualitative studyPatient Relat Outcome Meas20123394923185121

- EtonDRidgewayJEggintonJFinalizing a measurement framework for the burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditionsPatient Relat Outcome Meas2015611712625848328

- GallacherKMorrisonDJaniBUncovering treatment burden as a key concept for stroke care: a systematic review of qualitative researchPLoS Med2013106e100147323824703

- DolovichLRNairKMCiliskaDKThe diabetes continuity of care scale: the development and initial evaluation of a questionnaire that measures continuity of care from the patient perspectiveHealth Soc Care Community200412647548715717895

- RoeDGoldblattHBaloush-KlienmanVSwarbrickMDavidsonLWhy and how people decide to stop taking prescribed psychiatric medication: exploring the subjective process of choicePsychiatr Rehabil J2009331384619592378

- LoremGFFrafjordJSSteffensenMWangCEMedication and participation: a qualitative study of patient experiences with antipsychotic drugsNurs Ethics201421334735824106257

- GoodhueDLLoiaconoETRandomizing survey question order vs. grouping questions by construct: an empirical test of the impact on apparent reliabilities and links to related constructsSystem sciences2002 Available from: https://www.computer.org/csdl/proceedings/hicss/2002/1435/08/14350254.pdfAccessed October 16, 2016