Abstract

Background

Pneumonia has been the leading cause of morbidity and mortality among children under 5 for more than 3 decades, particularly in low-income countries like Bangladesh. The World Health Organization (WHO) developed a pneumonia case management strategy which included the use of antibiotics for both primary and hospital-based care. This study aims to describe antibiotic usage for treating pneumonia in children in a private pediatric teaching hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Methods

We conducted this cross-sectional study among children <5 years old who were admitted to a private pediatric hospital in Dhaka with a diagnosis of pneumonia in November 2012.

Results

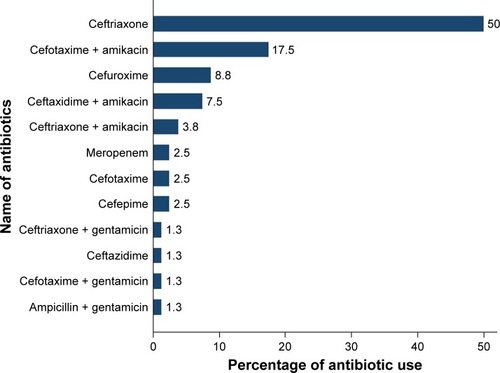

We enrolled 80 children during the study period. Among them, 28 (35.4%) were underweight, 14 (17.7%) were moderately underweight, and 13 (16.5%) were severely under-weight. On the basis of WHO classification (2005), 43 children (54%) had severe pneumonia and 37 (46%) had very severe pneumonia, as diagnosed by the research physician. Among the prescribed antibiotics in the hospital, parenteral ceftriaxone was the most common 40 (50%), followed by cefotaxime plus amikacin 14 (17.5%), cefuroxime 7 (8.8%), ceftazidime plus amikacin 6 (7.5%), ceftriaxone plus amikacin 3 (3.8%), meropenem 2 (2.5%), cefepime 2 (2.5%), and cefotaxime 2 (2.5%).

Conclusion

Despite the WHO pneumonia treatment strategy, the inappropriate use of higher-generation cephalosporin and carbapenem was high in the study hospital. The results underscore the noncompliance with the WHO guidelines of antibiotic use and the importance of enforcing regulatory policy of the rational use of antibiotics for treating hospitalized children with pneumonia. Following these guidelines may help prevent increased antimicrobial resistance.

Introduction

Globally, pneumonia is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality and accounted for 16% of the estimated 5.9 million deaths among children aged <5 years in 2015.Citation1 In 2010, there were 120 million episodes of pneumonia in children younger than 5 years, and 14 million pneumonia cases progressed to severe and life-threatening conditions requiring urgent hospital care.Citation2 In 2011, about 1.3 million estimated pneumonia cases led to death worldwide.Citation2 Pneumonia is one of the leading causes for hospital admission among children under 5 years of age in pediatric hospitals in Bangladesh.Citation3 Among the estimated 119,000 under-five deaths in Bangladesh, 15% were due to pneumonia.Citation1

In 1980, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed a case-management strategy known as the Acute Respiratory Infection (ARI) program in an attempt to reduce pneumonia-related deaths. Thereafter, in 1995, this strategy was incorporated into the guidelines of the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) for primary care and hospital-based case management. In 2005, the IMCI guidelines were incorporated in the WHO Pocket Book for pediatric hospital care with some amendments, especially for physicians. The impact of these guidelines has been enormous. Over the decades, death from pneumonia in children under five dropped from 2.3 million in 1990 to 0.9 million in 2015.Citation1 However, studies in many countries have reported that health workers are not adhering to the IMCI guidelines in disease diagnosis, antibiotic prescription, and referrals.Citation4–Citation7 In addition, there is a scarcity of research from referral hospitals that assess adherence to the IMCI guidelines.Citation6 Before 2013, the IMCI guidelines were based on low-quality evidence and that might have had an impact on antibiotic use among clinicians at referral centers. In 2013, the WHO revised the classification of pneumonia and the treatment regimen on the basis of high-quality up-to-date evidence, aiming to improve the quality of care and reduce deaths especially in resource-poor settings. Additional aims of the revision were to increase utilization of the guidelines by physicians, nurses, and senior health workers responsible for treating young children at primary health care centers.Citation8

Antibiotics are the most frequently prescribed medicament for acute respiratory tract infections and acute watery diarrhea.Citation9,Citation10 According to the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (2013), 71.4% of under-five children received antibiotics for ARI or pneumonia from a health facility or treatment provider.Citation11 A study conducted in the south-west of Bangladesh showed that cephalosporins accounted for 31.8% of total antibiotic prescriptions, and among them, cefixime, cefuroxime, and ceftriaxone were highly used for respiratory and other infections and 83% prescriptions were used irrationally without any positive microbial test.Citation10 According to the WHO, common health care-associated and community-acquired pneumonia are now caused by highly resistant bacteria in all WHO regions.Citation12 In Bangladesh, studies have shown antibiotics use on pediatric and adult patients at a medical university and regional health complexes for a variety of diseases, including ARI or pneumonia.Citation13–Citation15 However, there remains scarce information regarding antibiotic practices in cases of severe and very severe pneumonia among children under 5 years in private hospitals. In this study, we aimed to describe antibiotic practice for treating pneumonia among children under 5 years of age in a private pediatric teaching hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Methodology

From 13th to 23rd of November 2012, we conducted a cross-sectional study among children under 5 years of age admitted with a diagnosis of pneumonia at a private pediatric teaching hospital in Dhaka.

Using a 95% CI and 10% precision, we assumed that 71% of pneumonia patients would receive first-line treatment with antibioticsCitation11 and calculated a total sample size of 80.

Children of either sex, under 5 years of age with a clinical diagnosis of pneumonia according to WHO Pocket Book (2005)Citation16 irrespective of pneumonia etiology, admitted within the given time period in the study hospital, were enrolled after having informed consent of the parents. Children with comorbidities such as congenital heart disease, meningitis, and chronic respiratory diseases such as chronic suppurative lung disease and tuberculosis reported in the patient history form were excluded. We followed WHO criteriaCitation16 to develop the operational definitions of childhood pneumonia.

Pneumonia

The case definition of pneumonia included children presenting with cough and difficulty in respiration having age-specific fast breathing (≥50 breaths/minute for 2 to <12 months of age and ≥40 breaths/minute for 12–59 months of age). Fever (T ≥38.0°C) may or may not be present for diagnosis.

Severe pneumonia

The case definition of severe pneumonia included children presenting with cough and difficulty in respiration having ≥60 breaths/minute and/or lower chest wall in-drawing (0 to <2 months), and lower chest wall in-drawing irrespective of the presence or absence of the age-specific fast breathing.

Very severe pneumonia

Very severe pneumonia included patients with cough or difficulty breathing with any of the following danger signs – central cyanosis, inability to breastfeed or drink, or uncontrollable vomiting, convulsion, lethargy or unconsciousness, or severe respiratory distress (eg, head nodding).

Data collection instruments and tools

A pretested structured questionnaire was used to collect demographic information, monthly income status, clinical presentation, physical findings, immunization history, exclusive breast feeding history, nutritional status, past medical history, history of antibiotic use prior to hospitalization, treatment providers prior to hospitalization, primary diagnosis, additional diagnosis or comorbidities diagnosed by the hospital’s physicians, diagnosis made by the researcher, and antibiotic prescription after hospitalization. Hospital registration number, primary diagnosis, additional diagnosis or comorbidities reported by the hospital’s physicians, and the treatment prescribed during hospitalization were collected from the participants’ history form at the hospital. Additional diagnosis or comorbidities included febrile convulsion, septicemia (seriously ill with no apparent cause, purpura, petechiae, shock, and hypothermic young infant or severely malnourished child), bronchial asthma (recurrent episodes of shortness of breath or wheeze), enteric fever (fever with any of the following: diarrhea or constipation, vomiting, abdominal pain, headache, and cough, particularly if the fever has persisted for ≥7 days),Citation16 acute gastroenteritis, childhood obesity,Citation17 and cerebral palsy.

Stethoscope, blood pressure machine, timer, length/height scale, weight scale, mid upper arm circumference tape, and digital thermometer were used for data collection.

Data management and statistical analysis

According to the WHO Pocket Book (2005),Citation16 we stratified the children into three age groups for diagnostic purposes. Z scores were calculated using the new child growth standards of the WHO.Citation18,Citation19 Children with a Z score for their median weight >−1 were considered as not underweight, −1 to >−2 as underweight, −2 to >−3 as moderately under-weight, and <−3 as severely underweight.

The data were entered using SPSS 20 and analyzed using STATA 12. To calculate the weight-for-age Z score, WHO Anthro software v3.2.2 was used. Continuous variables were reported by the mean value or median value and range. Pearson’s chi-squared test was used for bivariate analysis to show the association between antibiotic use, age of patients, clinical findings, chief complaints, and comorbidities.

Ethical consideration

Data were collected from each participant after receiving informed written consent by explaining explicitly the objectives and procedures of the study to the parents or the caregiver of the participants. The study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of James P Grant School of Public Health, BRAC University.

Findings

We enrolled 80 children from the study hospital during the given time period. Most of the participants were male (72.5%) and 41% were aged between 3 and 12 months (). Thirty percent of the children were not under-weight, 41% were exclusively breastfed, and 53.7% received their vaccinations according to the expanded program on immunization schedule. The monthly household income was <188 USD (1 USD =80 Bangladeshi taka) for 47.5% participants, 86.4% of the children’s primary caregivers were their mothers, and 28.7% of the participants were admitted from outside of Dhaka ().

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of hospitalized pneumonia children in a private pediatric hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh, November, 2012

The study participants (80; 100%) were diagnosed as pneumonia by the hospital’s physicians. However, according to the WHO classification,Citation16 43 (53.8%) were diagnosed as severe pneumonia and 37 (46.3%) as very severe pneumonia by the study physician.

Among the study participants, 77 (96.3%) suffered from cough, 77 (96.3%) from breathlessness and fast breathing, 71 (88.8%) from a loss of appetite, 55 (68.8%) from fever, 54 (67.5%) from runny nose, 34 (42.5%) from vomiting, and 8 (10.1%) from convulsion. The median duration of the runny nose was 5 days (interquartile range [IQR] =3–7), cough was 5 days (IQR =3–7), breathlessness and fast breathing was 3 days (IQR =2–4), loss of appetite was 3 days (IQR =2–4), fever was 2 days (IQR =1–4), vomiting was 2 days (IQR =1–3), and convulsion was 1 day (IQR =1–3). Among the participants, 5 (6.3%) had associated comorbidities including febrile convulsion, 2 (2.5%) septicemia, 2 (2.5%) acute gastroenteritis, 1 (1.3%) bronchial asthma, 1 (1.3%) childhood obesity, 1 (1.3%) cerebral palsy, and 1 (1.3%) enteric fever.

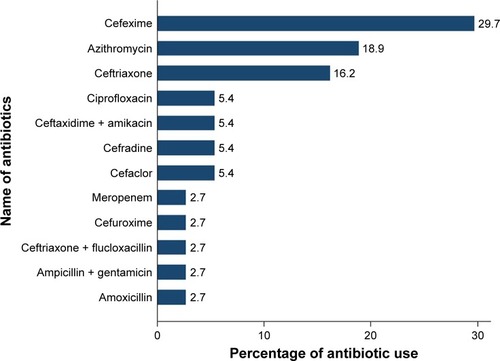

After hospital admission, both single and a combination of double antibiotics were used (). In most of the cases, third-generation cephalosporin was prescribed. Fifty-eight (72.5%) participants were admitted for the first time in the hospital in their life time. Fifty-eight (72.5%) participants received treatment from physicians and 1 (1.3%) from a drug seller in a pharmacy before hospitalization. Among them, 37 (46.3%) were prescribed antibiotics and the median duration of antibiotic use prior to admission was 2 days (IQR =1–3). A wide range of oral to injectable antibiotics were used by the participants prior to hospital admission ().

Figure 1 Use of antibiotics by the hospital physicians among the hospitalized pneumonia children in a private pediatric teaching hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh, November, 2012.

Figure 2 Antibiotics used before hospitalization among the hospitalized pneumonia children in a private pediatric teaching hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh, November, 2012.

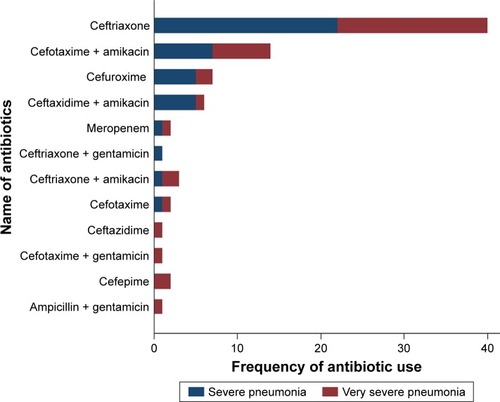

For both severe and very severe pneumonia, ceftriaxone was the most commonly prescribed antibiotic after hospitalization (). Cefuroxime was prescribed more often for severe pneumonia patients when compared with those who had very severe pneumonia. Ceftazidime, cefotaxime plus gentamycin, cefepime, and ampicillin plus gentamycin were prescribed only to 5 (13.5%) participants diagnosed as very severe pneumonia ().

Figure 3 Difference in using antibiotics for treating severe pneumonia and very severe pneumonia in hospital among the hospitalized pneumonia pediatric patients in a private pediatric teaching Hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh, November, 2012.

Among the prescribed antibiotics, ceftriaxone (P<0.001) and the combination of cefotaxime and amikacin (P=0.01) were found to be significantly associated with the age of the participants (). Ceftazidime plus amikacin was associated with auscultatory crepitation in lungs (P=0.04). Cefuroxime was associated with the chief complaints of breathlessness, cold, and crying (P=0.01) and patients having no other comorbidity (P=0.01) ().

Table 2 Association of antibiotic use with demographic information, history of illness, and clinical findings of the patients admitted with pneumonia in a private pediatric teaching hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh, November, 2012

Discussion

The most important observation of this study was the lack of adherence to WHO guidelines for diagnosing and treating pneumonia by the hospital’s physicians. All children admitted with severe pneumonia and very severe pneumonia received a wide range of extended spectrum antibiotics through a parenteral route. A study conducted in 10 upazila health complexes in Dhaka and Noakhali district of Bangladesh also showed that injectable antibiotics were used in 100% of ARI/pneumonia encounters at 4 out of 5 upazila health complexes in Dhaka District.Citation20 According to Akter et al,Citation21 the commonly used antibiotics in Bangladesh were ampicillin, gentamicin, amoxicillin, cloxacillin, and ceftriaxone for treating pneumonia and diarrhea for all the pediatric age groups; however adherence to WHO guide-lines was not evaluated in the study. At a tertiary hospital in Malaysia, the commonly used antibiotics were amoxicillin with clavulanate (augmentin) followed by erythromycin, cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, and ampicillin with sulbactum sodium, irrespective of the patients’ age group, which may lead to inappropriate prescription of antibiotics and which might be influenced by physicians’ personal choice and limited experience.Citation22 Our findings showed that ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, amikacin, cefuroxime, and ceftazidime were commonly used for the treatment of pneumonia after hospital admission. Among the severe pneumonia cases, 67.4% were treated with third-generation cephalosporin and second-generation cephalosporin, carbapenem, and 32.6% cases were treated with a combination of two antibiotics such as cefotaxime plus amikacin, ceftazidime plus amikacin, ceftriaxone plus gentamicin, and ceftriaxone plus amikacin. On the contrary, among the very severe pneumonia cases, 67.6% were treated with fourth-generation cephalosporin, third-generation cephalosporin, and second-generation cephalosporin, carbapenem, and 29.7% were treated with a combination of two drugs such as cefotaxime plus amikacin, ceftriaxone plus amikacin, ceftaxidime plus amikacin, cefotaxime plus gentamicin, and ceftriaxone plus gentamicin other than ampicillin plus gentamicin. The use of antibiotics during admission was high compared to the results of a previous study conducted by Akter et alCitation21 in Bangladesh. It also appeared that physicians in primary health care in that country have antibiotic preference for the cephalosporin group.Citation14 Antibiotic use is influenced by the personal preference of hospital physicians, limited experience, availability of antibiotics, and the potential effects of marketing by pharmaceutical industries.Citation22 The use of higher-generation of cephalosporin and carbapenem by the physicians may occur due to less empirical evidence on antibiotic use provided by WHO before 2013.

Our study findings suggest that 72.5% of patients received treatment before hospitalization. Among them, 46.3% received antibiotics prior to hospitalization, which is consistent with a previous study conducted in Bangladesh (44%).Citation3 According to our study, 94.6% of antibiotics used for first-line treatment before hospitalization were cefixime, azithromycin, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, ceftaxidime plus amikacin, cefradine, cefaclor, meropenem, cefuroxime, and ceftriaxone plus flucoxacillin other than ampicillin plus gentamicin, and amoxicillin. In our study, we observed that 100% patients, diagnosed as severe or very severe pneumonia, received injectable antibiotics and among them 98.7% patients received ceftriaxone, cefotaxime plus amikacin, cefuroxime, ceftaxidime plus amikacin, ceftriaxone plus amikacin, meropenem, cefotaxime, cefepime, ceftriaxone plus gentamicin, ceftazidime, and cefotaxime plus gentamicin as first-line treatment other than a combination of ampicillin plus gentamicin. These antibiotics prescribed by qualified physicians or drug sellers prior to hospitalization may have an influence on antibiotic practices in the inpatient department of hospitals after admission.

In our study, we followed the WHO Pocket Book (2005)Citation16 to identify adherence of the hospital’s physicians to diagnose, classify, and treat pneumonia. All enrolled patients were diagnosed with pneumonia by the hospital physicians. The hospital physicians did not classify pneumonia according to the WHO guidelines, which is crucial for appropriate treatment. Following the WHO Pocket Book (2005),Citation16 the study physician diagnosed 54% patients as having severe pneumonia and 46% as having very severe pneumonia. We observed that all the patients were treated similarly with antibiotics without any classification of pneumonia or prior investigations like blood cultures and sensitivity tests. To properly treat patients and prescribe antibiotics, physicians should define the illness and severity of illness with clinical judgment and microbiological evidence. This may in turn also reduce the cost of treatment.

According to WHO Pocket Book (2005),Citation16 severe pneumonia should be treated with oral amoxicillin and very severe pneumonia with parenteral ampicillin or benzyl-penicillin and gentamicin as first-line treatment and accordingly ceftriaxone should be used as a second-line treatment in case of failure of the first-line treatment. In the revised WHO classification, pneumonia was defined as having fast breathing and/or chest indrawing, which needs to be treated at home with oral amoxicillin as first-line treatment (azithromycin as second-line treatment in case of first-line treatment failure), and “severe pneumonia” was defined as having any general danger sign with or without fast breathing which requires referral to hospitals for injectable therapy (ampicillin plus gentamicin as first-line treatment and ceftriaxone as second-line treatment in case of first-line treatment failure).Citation8 In our study, among the suggested antibiotics by WHO, amoxicillin and ampicillin plus gentamicin were used in 5% of cases irrespective of diagnosis before hospitalization, and ampicillin plus gentamicin was used only in 3% cases of very severe pneumonia (n=37) after hospitalization. This revealed very low adherence to pneumonia treatment guidelines. However, Afreen and RahmanCitation13 showed low (3%) adherence to treatment guidelines including antibiotics and other drugs in pneumonia among the pediatric age group patients in a medical university in Bangladesh. Furthermore, our study reported the use of amikacin among children under 5 years of age, which is something noteworthy for physicians. Aminoglycosides such as amikacin should be used cautiously as it may have clinical toxicities like ototoxicity or nephrotoxicity.Citation23

We also found associations of antibiotic use with the age of the patient, respiratory auscultation findings, and chief complaints of the patients. A study conducted in India showed nonassociation of antibiotic practice with comorbidities and association with symptoms of illness, which supports our study findings.Citation24

Limitations of the study

This study was conducted within a short period of time during winter. For this reason, we were not able to identify seasonal variations in antibiotic practice. The study was conducted in a private pediatric teaching hospital in Dhaka city, the scenario of which may differ from a government hospital where physicians are most likely to have undergone IMCI training in accordance with WHO guidelines. Hence, the study findings might be generalized for private hospitals only where pediatric patients are treated.

Conclusion

The results of our data suggest that the use of injectable antibiotics was high in the private hospital which did not follow the WHO standard treatment guidelines. The observation emphasizes the importance of adherence to high-quality evidence based on recent WHO classification and treatment in accordance with the severity of pneumonia. Enforcing regulatory policy is the need of the hour, which may help to increase the rational use of antibiotics in treating hospitalized children with pneumonia and consequently may prevent increased antimicrobial resistance. However, more researches are sine qua non to identify the seasonal variations of antibiotic practice on the basis of their blood culture and sensitivity both in private and government hospitals following the WHO Pocket Book (2013).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge gratefully James P Grant School of Public Health and MPH Program, the hospital authority, for its support and cooperation. We are grateful to all of the study participants and their parents or caregivers for their patience and for sharing information. We are also thankful to our research assistant Aklima Tasrin for her contribution in data collection. International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) also gratefully acknowledges the following donors who provided unrestricted support: Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Global Affairs Canada, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, and the Department for International Development. The research study was funded by James P Grant School of Public Health, BRAC University, Bangladesh for partial accomplishment of Master of Public Health.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- UNICEFCommitting to Child Survival: A Promise Renewed-Progress Report 2014New York, NYUnited Nations Children’s Fund2015 Available from: http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/APR_2015_9_Sep_15.pdfAccessed July 31, 2017

- WalkerCLFRudanILiuLGlobal burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoeaLancet201338198751405141623582727

- NaheedASahaSKBreimanRFPneumococcal Study GroupMultihospital surveillance of pneumonia burden among children aged <5 years hospitalized for pneumonia in BangladeshClin Infect Dis200948Suppl 2S82S8919191623

- KiplagatAMustoRMwizamholyaDMoronaDFactors influencing the implementation of integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) by healthcare workers at public health centers & dispensaries in Mwanza, TanzaniaBMC Public Health201414127724666561

- LangeSMwisongoAMæstadOWhy don’t clinicians adhere more consistently to guidelines for the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI)?Soc Sci Med2014104566324581062

- MulaudziMCAdherence to case management guidelines of Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) by healthcare workers in Tshwane, South AfricaSAJCH South African J Child Heal201593899210.7196/SAJCH.7959

- SennNRarauPSalibMUse of antibiotics within the IMCI guidelines in outpatient settings in Papua New Guinean children: an observational and effectiveness studyPLoS One201493e9099024626194

- WHO Pocket BookPocket Book of Hospital Care for Children: Guideline for the Management of Common Childhood Illness2nd ed2013 Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/81170/1/9789241548373_eng.pdf?ua=1Accessed July 31, 2017

- RashidAChowdhuryARahmanSHZBegumSAMuazzamNInfections by pseudomonas aeruginosa and antibiotic resistance pattern of the isolates from Dhaka Medical College HospitalBangladesh J Med Microbiol2007124851

- BiswasMRoyDTajmimAPrescription antibiotics for outpatients in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional health survey conducted in three citiesAnn Clin Microbiol Antimicrob2014131524755269

- NIPORT, Associates M and, International IBangladesh Demographic and Health Survey2013 Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr265/fr265.pdfAccessed July 31, 2017

- WHOAntimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on SurveillanceGenevaWorld Health Organization2014 Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112642/1/9789241564748_eng.pdfAccessed July 31, 2017

- AfreenSRahmanMSAdherence to treatment guidelines in a university hospital: Exploration of facts and factorsBangladesh J Pharmacol201492182188

- HasanSMRHossainMMAkterRPattern of antibiotics use at the primary health care level of Bangladesh: survey report-1Stamford J Pharm Sci20092117

- FahadBMMatinAShillMCAsishKDAntibiotic usage at a primary health care unit in BangladeshAustralas Med J201037414421

- WHO Pocket BookPocket Book of Hospital Care for ChildrenGenevaWorld Health organization2005 Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2005/9241546700.pdfAccessed July 31, 2017

- WHOWhat is overweight and obesity? [webpage on the Internet]GenevaWorld Health Organization2012 Available from: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood_what/en/index.htmlAccessed July 31, 2017

- WHOWeight-for-age BOYS Child growth standardsGenevaWorld Health Organization2012 Available from: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/WFA_boys_0_5_zscores.pdfAccessed July 31, 2017

- WHOWeight-for-age GIRLS Child growth standardsGenevaWorld Health Organization2012 Available from: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/WFA_girls_0_5_zscores.pdfAccessed July 31, 2017

- ChowdhuryAKRahmanSMFaroqueABHasanGARaihanSZExcessive use of avoidable therapeutic injections in the upazilla health complexes of BangladeshMymensingh Med J2008172S59S6418946453

- AkterSFHellerRDSmithAJMillyAFImpact of a training intervention on use of antimicrobials in teaching hospitalsJ infect Dev Ctries20093644745119762958

- AkterSFRaniMFARahmanJAAntimicrobial use and factors influencing prescribing in medical wards of a tertiary care hospital in MalaysiaInt J Sci Environ Technol201214274284

- AventMLRogersBAChengACPatersonDLCurrent use of aminoglycosides: Indications, pharmacokinetics and monitoring for toxicityIntern Med J201141644144921309997

- SKIChandySJJeyaseelanLKumarRSureshSAntimicrobial prescription patterns for common acute infections in some rural & urban health facilities of IndiaIndian J Med Res2008128216517119001680