Abstract

Background

Hemophilia is marked by frequent joint bleeding, resulting in pain and functional impairment.

Objective

This study aimed to assess the reliability of five patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments in people with hemophilia (PWH) in a non-bleeding state.

Methods

Adult male PWH of any severity and inhibitor status, with a history of joint pain or bleeding, completed a pain history and five PRO instruments (EQ-5D-5L, Brief Pain Inventory v2 [BPI], International Physical Activity Questionnaire [IPAQ], Short Form 36 Health Survey v2 [SF-36v2], and Hemophilia Activities List [HAL]) during their routine comprehensive care visit. Patients were approached to complete the PRO instruments again at the end of their visit while in a similar non-bleeding state. Concordance of individual questionnaire items and correlation between domain scores were assessed using intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC).

Results

Participants completing the retest (n=164) had a median age of 33.9 years. Median time for completion of the initial survey with PRO instruments was 36.0 minutes and for the five PRO instruments, median retest time was 21.0 minutes. The majority of participants had hemophilia A (74.4%), were white and non-Hispanic (72.6%), and self-reported arthritis/bone/joint problems (61%). Median/mean test-retest concordance was EQ-5D-5L 80.0%/79.1%, BPI 54.5%/58.9%, IPAQ 100%/100%, SF-36v2 77.8%/76.4%, and HAL 77.4%/75.9%. ICCs for test-retest reliability were EQ-5D-5L index 0.890; BPI – severity 0.950; BPI – interference 0.920; IPAQ total activity 0.940; SF-36v2 overall health 0.910; HAL total score 0.970.

Conclusion

All five PRO scales showed acceptable test-retest reliability in adult PWH. Therefore, the choice of instrument to be used for research or clinical care should be driven by instrument characteristics other than reliability.

Introduction

Hemophilia is an inherited coagulopathy that results in acute bleeding, causing frequent pain and joint damage.Citation1,Citation2 Over time, recurring cycles of acute inflammation and swelling can lead to chronic pain and arthropathy.Citation3,Citation4 With an increase in life expectancy among people with hemophilia (PWH), there has been a greater focus on managing comorbidities associated with hemophilia, including pain.Citation5 However, limited data are available on the prevalence and impact of pain in adult PWH.

Pain is inconsistently assessed both in clinical studies and in clinical practice.Citation6,Citation7 A survey of 22 European centers by the European Treatment Standardization Board found that although 67% of their patients experienced arthropathy and 35% reported chronic pain, only eight of the centers used any formal pain assessment scales, and only two centers used the services of a pain specialist.Citation8 Similarly, in a survey of 98 US hemophilia treatment centers (HTCs), only 15% of responding centers reported having pain management as part of comprehensive care.Citation9 Within hemophilia, some instruments may be better able to assess pain at early stages of joint disease (eg, soft tissue changes from acute or chronic synovitis, joint space distension from acute bleeding) when impact on functional impairment is less pronounced; others might be more appropriate at later stages of the disease to assess both pain and functional impairment associated with joint damage resulting in chronic arthropathy (eg, cartilage and bone changes, compromised range of motion, secondary muscle atrophy). While some studies in primary and secondary prophylaxis have employed quality-of-life (QoL) instruments, including disease-specific (eg, HAEMO-QoL and Hemophilia Activities List [HAL])Citation10–Citation13 and generic (Short Form 36 Health Survey [SF-36]) scales,Citation14–Citation16 the baseline characteristics of these populations are unknown, and the studies are confounded by small sample size, which affects the generalizability of their findings. Additionally, although some generic and disease-specific patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments have been used in studies of PWH, such as the HAL in the Netherlands, these have not been validated in adults with hemophilia in the USA. Currently, there are no data on Brief Pain Inventory Short Form (BPI) and EQ-5D-5L in US adult PWH and only limited data on SF-36v2Citation14–Citation17 in this population. Previous studies of the EQ-5D among PWH, such as the cross-sectional assessment in the Hemophilia Experiences, Results and Opportunities (HERO) studyCitation18 and daily assessment in the Dosing Observational Study in Hemophilia (DOSE),Citation19 used the 3-level scoring of the five domains, which may limit the instrument’s ability to discriminate among PWH with milder phenotypes compared with the 5-level version. Because joint damage develops gradually over decades and is difficult to track, there is a clear need to identify and validate scales that can be used in clinical practice and research to assess pain and its relationship to functional impairment.Citation6,Citation7

The Pain, Functional Impairment and Quality of Life (P-FiQ) study was developed to assess the impact of pain on functional impairment and QoL in US adult PWH, with or without inhibitors, with joint bleeding, pain, or both. Previous surveys of adult PWH have been limited by opt-in bias and a lack of validated or comprehensive instruments that can capture both pain severity and interference with activities. As a result, the impact of pain in adult PWH in the USA has not been captured. Participants in the P-FiQ study completed qualitative, generic surveys that assessed the prevalence and characteristics of acute and chronic pain and gathered information on the strategies employed to manage pain among PWH, as well as the impact of pain on function and QoL. These data were also used to validate the existing general and disease-specific QoL/pain scales used in the study. Test-retest reliability assessment is part of an extensive psychometric evaluation, including other measures of reliability testing (eg, item-total correlation) and measures of content validity (construct validity, known-group validity, etc), that will be presented in detail separately in parallel publications.

The overall aim of this article is to describe the P-FiQ study, with a particular focus on the survey methodology and demographic characteristics of study participants, and to provide an assessment of the reliability of generic and disease-specific PRO instruments. Evaluating the reliability of these PRO scales will provide critical information about whether these measures would be potentially suitable for use in research and clinical practice in the future in the US adult PWH population. Given the current lack of consensus on assessing pain and associated functional impairment, validating at least one scale may help provide support for using these PRO instruments in clinical practice and assessment of research study cohorts.

Methods

This was a non-interventional, cross-sectional study in which adult PWH who were attending their annual or other routine periodic comprehensive care visit were approached for study recruitment (NCT01988532). Given the potential for adult PWH complicated by joint bleeding or joint pain to experience bleeds in one of the six most common index joints (ankles, knees, elbows) at least once or twice a month with a period of treatment of several days or longer,Citation20 the day-to-day variability in pain and health scores reported in adult PWH with inhibitors, and the potential for associated functional impairment that might persist related to the specific joint bleed past the end of treatment, it was determined that any assessment of test-retest reliability would need to be in a similar non-bleeding state. Furthermore, adult PWH often must travel up to 6–8 hours to reach an HTC, making it difficult to have multiple assessments over a period of days, particularly for working adults who need to take time off to travel to/from visits. For these reasons, the test-retest reliability assessment was planned to span the normal 3–4 hour routine outpatient comprehensive care visit at the HTC.

The study protocol was approved by the local institutional review board (IRB) or central IRB. A list of each approving IRB is provided in Box S1. Written informed consent was obtained from participants by researchers before engaging in study-related activities. There were no follow-up visits, no treatment was specified or provided, and no product-related information captured; therefore, no safety data were captured. Investigators were directed that any adverse drug reactions relating to treatment prior to the study visit should be reported using their standard procedures for reporting spontaneous adverse events.

Recruitment and study population

The overall P-FiQ study planned to capture 300 to 400 consecutive adult PWH in the USA. Of those enrolled, it was estimated that 250 to 300 adult PWH would complete the study and 120 to 150 would participate in the retest phase. To be eligible for inclusion, participants were required to be males aged 18 years and older with congenital hemophilia A or B with or without inhibitors and have a history of joint bleeding or joint pain. Individuals had to be visiting a treatment center for a routine comprehensive care visit while in a steady or non-bleeding state. Joint range of motion was assessed, and patients had to be capable of completing the survey in English. Exclusion criteria included previous participation in this study. Participants were recruited from October 2013 to October 2014 from 15 US HTCs, including some of the largest and smallest HTCs in the USA responding to feasibility questionnaires, with a mean (median) of 25.4 (28.0) participants per site. Each patient was assigned a unique study number to preserve patient confidentiality and compensated for participation in the study based on whether he completed the initial case report forms (CRFs), and additionally if he completed the five PRO instruments at the end of the visit.

Test-retest process

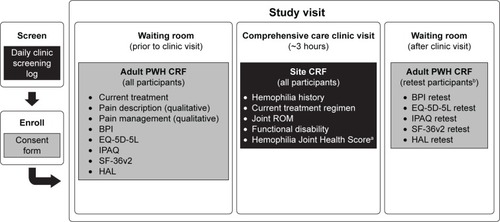

The study design is described in . Prior to the start of the comprehensive care visit, adult PWH completed part 1 of the CRF, which included sociodemographic information (education, employment), current hemophilia treatment, acute and chronic pain characteristics/descriptors and treatments, and five PRO instruments: EQ-5D-5L with visual analog scale (VAS; recall period: “today”), BPI (recall period: the last 7 days), International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ; recall period: the last week), SF-36v2 (recall period: the last 4 weeks), and HAL (recall period: previous month). Details regarding selection of the PRO instruments, scoring, and development history have been previously reported with the primary results of the PRO analysis.Citation21

Figure 1 Pain, Functional Impairment and Quality of Life (P-FiQ) study design.

Abbreviations: BPI, Brief Pain Inventory Short Form; CRF, case report form; HAL, Hemophilia Activities List; HJHS, Hemophilia Joint Health Score; HTC, hemophilia treatment center; IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire; PWH, people with hemophilia; ROM, range of motion; SF-36v2, Short Form 36 Health Survey v2.

During the comprehensive care visit, the physician or the physician’s associate completed part 2 of the CRF for all participants, which included demographics, hemophilia characteristics (diagnosis, hemophilia history, treatment, comorbidities), functional status (based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Universal Data Collection [CDC-UDC] template), joint range of motion (based on CDC-UDC template), and Hemophilia Joint Health Score v2.1, which was optional.

After completion of the comprehensive care visit, the first 150 participants who consented to complete the retest and were also in a similar non-bleeding state as when they took the initial PRO instruments completed part 3 of the CRF, which included the five PRO scales only: EQ-5D-5L with EQ-5D VAS, BPI, IPAQ Short Form, SF-36v2, and HAL. Time at initiation and completion of the test and retest were also captured for the participants.

For simplicity and to maximize the opportunity for sites with varying resources to try to recruit at least 75% of consecutive eligible participants, all CRFs were completed on paper. Data entry into the study database was performed by a contract research organization (Quintiles Outcome, Boston, MA, USA) with electronic edit checks and random data monitoring to assure accuracy of data entry.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and based upon a formal statistical analysis plan developed in advance of data collection. Data from participating sites were combined, and continuous variables were summarized by descriptive statistics as mean or median, standard deviation (SD) or quartiles (Q) (interquartile range [IQR], Q1 and Q3), and range (minimum and maximum). Total numbers of responses and percentages of responses for each category (including missing responses) and each item were calculated. Data from the study were either patient-reported or site-reported, which is clearly identified in tables/figures where applicable. The study was not powered for comparisons of reliability or validity assessments between the PRO instruments; since the different instruments included in this study contain different subsets of concepts, such analyses were not performed.

Test-retest reliability for the five scales has been primarily validated in other diseases (EQ-5D-5L, BPI, SF-36v2, and IPAQ) or in PWH other than US adults (HAL).Citation22–Citation32 Here, the test-retest reliability of the five PRO instrument scales was evaluated by correlating domain and/or global scores separately across the pre- and post-comprehensive exam visits (approximately 3–4 hours) using the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) assessing the source of variation as within target assuming one-way random effects (SAS proc glm, standard confidence intervals).Citation33 The general minimum test-retest reliability criterion for attributes that are expected to be relatively stable over time is 0.70, however, an ICC greater than 0.80 is recommended by the International Prophylaxis Study Group.Citation34,Citation35 Concordance serves as a measure of agreement between different measuring or rating approaches, and was performed to assess agreement between initial pre-visit PRO responses and subsequent post-visit retest responses. Concordance of pre- and post-visit responses was calculated for percentage of overall agreement (SAS proc univariate, standard confidence intervals), based on individual item responses to each of the questionnaires, with higher values corresponding to a greater level of agreement.

Results

Sociodemographics of retest population

Altogether, out of the 544 individuals with hemophilia who were screened, 381 were enrolled in the overall P-FiQ study. The first 187 individuals were asked to participate in a retest at the completion of the comprehensive care visit in order to generate a retest population of at least 150 with complete responses. Of these 187 participants, 164 (87.7%) completed the PRO retest, exceeding the target enrollment of 150; the additional 14 patients had completed the study with CRFs not yet received at the time the retest enrollment target was met and cohort closed, but were included in the retest analysis. The mean (median) age of the retest population was 37.1 (33.9) years (interquartile range [IQR] 26.9–46.0) (). The majority of the participants were white (72.6%), married or in a long-term relationship (65.2%), and did not live alone (84.3%). Most had completed at least some college or graduate education (62.6%), and were employed (80.8%).

Table 1 Sociodemographics of the retest population (n=164, unless otherwise indicated)

Hemophilia history and comorbidities

Most of the retest population had severe hemophilia A (74.4%; ), 6% currently with inhibitors. The mean/median age at inhibitor diagnosis was 15.9/12.0 years (range, 0.3–53 years), and 15.9% had either a current or past inhibitor titer higher than 0.5 Bethesda units/mL. When asked about comorbidities related to their condition, 61.0% of respondents reported arthritis/bone/joint problems. The majority of participants (60.9%) were overweight (32.9%) or obese (28.0%), and the mean (SD) body mass index was 27.3 (5.8) kg/m2 (range, 16.5–46.8). A history of intracerebral hemorrhage was reported by 13.4%, occurring at a mean (SD) age of 14.5 (16.0) years; of these, 22.7% reported that they continued to experience residual neurological problems. Among site-reported viral illnesses, hepatitis C virus (HCV) was more common than human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (49.4% vs 16.5%), and most individuals with HCV or HIV were either currently receiving or had previously received antiretroviral therapy. Data on psychological conditions among the retest population were also captured: 17.7% had site-reported depression, and about 25% of these individuals were currently receiving treatment; 10.4% had site-reported anxiety, and of these individuals 29.4% were being treated; and 12.2% self-reported stress as a psychological condition. When asked about medications taken in the past 6–8 hours, 38.2% reported clotting factor or other hemophilia treatment for prophylaxis or bleeding, 38.8% had taken over-the-counter or prescription pain medications, 9.2% had taken a medication for depression or anxiety, and 42.8% reported that they had not taken any medications.

Table 2 Clinical characteristics of the retest population (n=164, unless otherwise indicated)

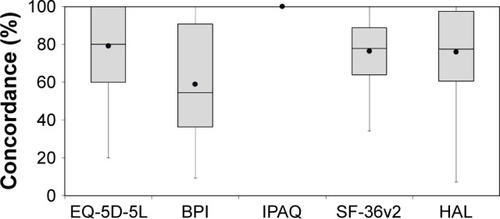

Concordance and reliability of PRO instruments

The median time to complete the initial survey with PRO instruments (which included the pain survey) was 36.0 minutes, and the mean (median) time for the five PRO retests (without the pain survey) was 25.4 (21.0) minutes. The mean/median time between tests was 1.63 hours/1.52 hours. The mean/median test-retest concordance percentage for each patient was calculated based on individual item responses to each of the questionnaires and ranged from 0% to 100% (). The overall mean/median concordance of each PRO instrument was then calculated based upon individual concordance scores. Of the PRO instruments, BPI had the least concordance of test-retest item responses, with a mean (median) concordance of 58.9% (54.5%). The IPAQ had the highest mean/median concordance (100%/100%), followed by EQ-5D-5L index (79.1%/80.0%), SF-36v2 (76.4%/77.8%), and HAL (75.9%/77.4%).

Figure 2 Concordance of individual item responses.

Abbreviations: BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; HAL, Hemophilia Activities List; IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire; SF-36v2, Short Form 36 Health Survey v2.

The test-retest reliability of each questionnaire was assessed by the ICC (). All ICCs achieved the 0.70 minimum, except for the IPAQ subdomain “Walking activity”, which had an ICC of 0.390. In general, the mental health subdomains of the SF-36v2 had lower ICCs relative to the physical health subdomains (“Mental health summary”, 0.810; “Physical health summary”, 0.940). When asked to rate the impact of pain on activities involving the upper and lower extremities on the HAL instrument, there was lower reliability among responses for the “Upper extremity activities” subdomain (0.870) compared with either the “Basic lower extremity activities” subdomain (0.950) or the “Complex lower extremity activities” sub-domain (0.960).

Table 3 Test-retest reliability of each PRO instrument

Discussion

Documenting patient-reported pain and the degree to which it affects quality of life for patients in the hemophilia community is a challenge for health care providers and HTCs. Scales such as the EQ-5D, SF-36, IPAQ, and HAL have been used previously in studies of PWH and validated in other diseases,Citation24,Citation26,Citation29,Citation31,Citation36,Citation37 but they have not been validated for use in adults with hemophilia in the USA.Citation14–Citation17 The P-FiQ study is the first study to use and validate the generic and disease-specific PRO instruments in US adults with hemophilia. Both the HERO study,Citation18 the largest comprehensive global study to include pain and QoL assessments, and the DOSE studyCitation20 have applied the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-VAS to the hemophilia patient population. Use of the EQ-5D-3L, however, was limited in only having three response levels to assess health status and might underestimate the impact of arthropathy by forcing patients to choose between the floor of none/no and the middle category of moderate/severe.Citation38 The P-FiQ study therefore represents the first use of the new 5-level, validated version in hemophilia.Citation28,Citation39

To account for the presence of potential bleed-related confounding variables (bleed/no bleed at retest, time since last bleeding event, location and severity of last bleeding event, impact of bleed location on specific functional capabilities), the study was designed to allow only a short duration between the administration of the initial PRO test and the PRO retest (after the comprehensive care visit, expected ~3–4 hours). Test-retest reliability is typically performed by administering a second test at a later time, up to 4 weeks; however, based on an estimate from the DOSE study that 8% of days in a 3-month period in PWH with inhibitors are days associated with bleeding episodes, it is possible that responses would be different if the questionnaire retest was administered 1 or 2 weeks following an annual visit, even in patients without inhibitors.Citation20 Because patients typically do not travel for comprehensive visits during or immediately following a bleed, there is potential that following the annual visit, the QoL of the patients would be different from that reported in the initial test, as it relates to the time frame of the different scales (EQ-5D, “today”; BPI, “the last week”; IPAQ, “the last 7 days”;Citation31 SF-36v2 and HAL, “previous month”Citation25,Citation33). Furthermore, potential long distances to an HTC could bias the population that would be available for a retest to those in more urban areas near the HTC. Unlike other chronic disorders in which day-to-day variability may be low, waiting 10 to 14 days for a retest in adult PWH might result in a falsely negative assessment of test reliability; therefore, participants in the retest phase were required to be in a similar non-bleeding state as in the initial test. It is conceivable that over the course of the comprehensive care visit, the health status of participants could change as medications that affect pain or physical function begin to wear off, or there could be an impact of the comprehensive visit itself (eg, testing of joint range of motion or gait) on functional abilities and QoL; however, this would likely be captured in the EQ-5D-5L, which assesses changes within the relevant time frame of “today”. Based on the concordance and ICC data for this instrument, it is unlikely that there was a change in the bleeding state following the physical therapy portion of the comprehensive care visit. The BPI has a time frame of 1 week, and going through physical evaluation over several hours certainly could impact current pain, as well as indirectly impact worst/average pain experienced during the last week. BPI was associated with the lowest concordance, suggesting that even going through a routine visit could impact PRO instruments measuring pain-related concepts. Therefore, performing the retest 3–4 hours after the conclusion of the comprehensive visit was judged to be ideal in balancing the potential for capturing a high percentage of consecutive patients with ensuring that patients present while in a similar enough general health state compared to the prior evaluation.

To represent patients with hemophilia who have joint bleeding and those affected by arthropathy, participants were included regardless of factor level. Additionally, the setting of a treatment center (HTC or elsewhere) for a comprehensive care visit was selected because it is generalizable to the adult PWH population. For purposes of assessing reliability and validity of the PRO instruments, it was simpler to conduct the study only with those who were able to complete the PRO instruments in English, because all of the instruments have been validated in hemophilia or another disease state in English. While mindful that a substantial proportion of PWH in the USA are Hispanic and that some of these patients might be more comfortable completing PRO instruments in Spanish, individuals with severe hemophilia A or B with reported Hispanic ethnicity account for only ~12% to 14% of US PWH.

The primary limitation of the study design is the potential for respondent fatigue due to the numerous scales to be completed before the visit and then again during the retest phase. While it is possible that some participants may recall their survey responses due to the short time frame between the initial test and retest, there are over 100 questions across five PRO instruments, reducing the likelihood that response recall would impact concordance. There is also the possibility that some participants may try to rapidly complete the post-visit retest to be eligible for the compensation that was designed to alleviate the burden of completing the tests under such circumstances. However, based on the favorable concordance results, this does not appear to be a significant limitation. Similar high completion rates were also observed with the HERO study, an online patient survey of even greater length,Citation18 which may be attributed to the direct relevance of the survey material to patients, the often prolonged periods spent waiting during comprehensive care visits, and the small amount of monetary compensation being offered to participants spending an additional hour or more. Furthermore, while retest reliability is one component of validity and a key endpoint of the study, additional analyses of internal consistency, item-total correlation, and construct validity from the P-FiQ study are also planned for the future. Another potential limitation is that the very act of asking patients for their measurements of quality of life pre- and post-test could positively impact the retest population;Citation40 however, the ICC suggests that this is not relevant.

Conclusion

Test-retest analyses indicate that all five PRO instruments appear to be reliable in adult PWH. Each scale provides a different level of detail in describing the impact of hemophilia on pain and function in relation to both the number of questions and how specific they are; consequently, the scales have varied burdens of administration and utility. The retest reliability observations suggest that the choice of instrument to be used for research or clinical care should be driven by instrument characteristics other than reliability and that specific instruments should be tailored to the study design (eg, research on trends in overall study cohorts using short/broad instruments like the EQ-5D-5L) or clinical need for specific outcome assessment (eg, pain management plan or physical therapy intervention based on detailed information provided by the BPI or HAL).

Acknowledgments

The clinical study analyzed was sponsored by Novo Nordisk A/S. Statistical analysis plan and analyses were provided by Jennifer James, MS at Quintiles Outcome under direction of Kari Kastango, PhD, and Pattra Mattox, MS. Writing assistance was provided by Shawn Keogan, PhD, of ETHOS Health Communications in Yardley, Pennsylvania, and was supported financially by Novo Nordisk Inc., Plainsboro, New Jersey, in compliance with international Good Publication Practice guidelines. The abstract of this paper was presented at the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemosta-sis 2015 congress as a poster presentation. The poster’s abstract was published in the Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

Supplementary material

Munson Medical Center

1105 Sixth Street

Traverse City, MI 49684-2386

Emory University

1599 Clifton Road, 5th Floor

Atlanta, GA 30322

St Vincent Hospital and Health Care Center, Inc.

8402 Harcourt Road, Suite 805

Indianapolis, IN 46260

Western Institutional Review Board

3535 7th Avenue SW

Olympia, WA 98502-5010

Henry Ford Health System

CFP-Basement 046

2799 West Grand Boulevard

Detroit, MI 48202-2689

(Chairperson: Dr Timothy Roehrs, PhD)

Vanderbilt University

504 Oxford House

Nashville, TN 37232-4315

Western Institutional Review Board

1019 39th Avenue SE

Puyallup, WA 98374

University of Colorado Multiple

Institutional Review Board

13001 E 17th Place, Building 500, Room N3214

Aurora, CO 80045

Michigan State University

Olds Hall

408 West Circle Drive, 207

East Lansing, MI 48824

(Chairperson: Dr Ashir Kumar)

Oregon Health & Science University

3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road

Portland, OR 97239-3098

University of Minnesota

D528 Mayo Memorial Building

420 Delaware Street SE, MMC 820

Minneapolis, MN 55455

Rush University Medical Center

1653 West Congress Parkway

Chicago, IL 60612-3833

Wake Forest University Health Services

Medical Center Boulevard

Winston-Salem, NC 27157-1023

Georgetown University

37th and O Streets, NW

Washington, DC 20057

Disclosure

CL Kempton: grant/research support from Novo Nordisk Inc.; consultant for Baxter, Biogen, CSL Behring, Kedrion. M Wang: consultant for Novo Nordisk Inc.. M Recht: grant/research support from Baxter, Biogen Idec, Novo Nordisk Inc., Pfizer; consultant for Biogen, Kedrion, Novo Nordisk Inc. A Neff: grant/research support from Novo Nordisk Inc.; consultant for Alexion, Baxter, CSL Behring, Novo Nordisk Inc. AD Shapiro: consultant for Baxter BioScience, Novo Nordisk Inc., Biogen Idec, ProMetic Life Sciences, Kedrion Biopharma. A Soni: speakers bureau participant for CSL Behring and Novo Nor-disk Inc.; consultant for Bayer. R Kulkarni: grant/research support from Novo Nordisk Inc., Biogen, Baxter, Bayer; consultant for Novo Nordisk Inc., Biogen, Bayer, Baxter, Kedrion, BPL, Pfizer. TW Buckner: consultant for Bax-alta US, Genentech, and Novo Nordisk Inc. K Batt: grant/research support from Novo Nordisk Inc.; scientific advisor for Precision Health Economics. NN Iyer and DL Cooper: employees of Novo Nordisk Inc., the sponsor of the study. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Rodriguez-MerchanECPrevention of the musculoskeletal complications of hemophiliaAdv Prev Med2012201220127122778972

- Rodriguez-MerchanECEffects of hemophilia on articulations of children and adultsClin Orthop Relat Res19963287138653981

- RoosendaalGMauser-BunschotenEPDe KleijnPSynovium in haemophilic arthropathyHaemophilia1998445025059873782

- RoosendaalGLafeberFPPathogenesis of haemophilic arthropathyHaemophilia200612Suppl 311712116684006

- MannucciPMSchutgensRESantagostinoEMauser-BunschotenEPHow I treat age-related morbidities in elderly persons with hemophiliaBlood2009114265256526319837978

- HumphriesTJKesslerCMThe challenge of pain evaluation in haemophilia: can pain evaluation and quantification be improved by using pain instruments from other clinical situations?Haemophilia201319218118723039033

- RileyRRWitkopMHellmanEAkinsSAssessment and management of pain in haemophilia patientsHaemophilia201117683984521645179

- HolsteinKKlamrothRRichardsMCarvalhoMPérez-GarridoRGringeriAEuropean Haemophilia Therapy Standardization Board. Pain management in patients with haemophilia: a European surveyHaemophilia201218574375222530627

- ShapiroACooperDLU.S. survey of surgical capabilities and experience with surgical procedures in patients with congenital haemophilia with inhibitorsHaemophilia201218340040522168829

- BullingerMvon MackensenSFischerKPilot testing of the ‘Haemo-QoL’ quality of life questionnaire for haemophiliac children in six European countriesHaemophilia20028Suppl 2475411966854

- von MackensenSBullingerMHaemo-QoL GroupDevelopment and testing of an instrument to assess the quality of life of children with haemophilia in Europe (Haemo-QoL)Haemophilia200410Suppl 11725

- PollakEMuhlanHvon MackensenSBullingerMHaemo-Qol GroupThe Haemo-QoL Index: developing a short measure for health-related quality of life assessment in children and adolescents with haemophiliaHaemophilia200612438439216834738

- BaumgardnerJElonLAntunAPhysical activity and functional abilities in adult males with haemophilia: a cross-sectional survey from a single US haemophilia treatment centreHaemophilia201319455155723574421

- WitkopMLambingADivineGKachalskyERushlowDDinnenJA national study of pain in the bleeding disorders community: a description of haemophilia painHaemophilia2012183e115e11922171646

- WitkopMLambingAKachalskyEDivineGRushlowDDinnenJAssessment of acute and persistent pain management in patients with haemophiliaHaemophilia201117461261921323802

- KhawajiMAstermarkJBerntorpELifelong prophylaxis in a large cohort of adult patients with severe haemophilia: a beneficial effect on orthopaedic outcome and quality of lifeEur J Haematol201288432933522221195

- den UijlIBiesmaDGrobbeeDFischerKTurning severe into moderate haemophilia by prophylaxis: are we reaching our goal?Blood Transfus201311336436923149144

- ForsythALGregoryMNugentDHaemophilia Experiences, Results and Opportunities (HERO) Study: survey methodology and population demographicsHaemophilia2014201445123902228

- NeufeldEJRechtMSabioHEffect of acute bleeding on daily quality of life assessments in patients with congenital hemophilia with inhibitors and their families: observations from the dosing observational study in hemophiliaValue Health201215691692522999142

- YoungGSolemCTHoffmanKCapturing daily assessments and home treatment of congenital hemophilia with inhibitors: design, disposition, and implications of the Dosing Observational Study in Hemophilia (DOSE)J Blood Med2012313113823152717

- RechtMNeufeldEJSharmaVRImpact of acute bleeding on daily activities of patients with congenital hemophilia with inhibitors and their caregivers and families: observations from the Dosing Observational Study in Hemophilia (DOSE)Value Health201417674474825236999

- KemptonCLRechtMNeffAImpact of pain and functional impairment in US adult people with hemophilia (PWH): patient-reported outcomes and musculoskeletal evaluation in the pain, functional impairment, and quality of life (P-FiQ) studyBlood20151262339

- ShroutPEFleissJLIntraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliabilityPsychol Bull197986242042818839484

- CleelandCSRyanKMPain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain InventoryAnn Acad Med, Singapore19942321291388080219

- van GenderenFRWestersPHeijnenLMeasuring patients’ perceptions on their functional abilities: validation of the Haemophilia Activities ListHaemophilia20061213646

- CleelandCSThe Brief Pain Inventory: User GuideMD Andersen Cancer CenterHouston, Texas2009 Available from: https://www.mdanderson.org/documents/Departments-and-Divisions/Symptom-Research/BPI_UserGuide.pdfAccessed August 27, 2015

- de Andres AresJCruces PradoLMCanos VerdechoMAValidation of the Short Form of the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI-SF) in Spanish patients with non-cancer-related painPain Pract201515764365324766769

- EuroQol GroupEQ-5D-5L User Guide: Basic Information on How to Use the EQ-5D-5L Instrument. Version 2.1NetherlandsEuroQol Group2015 Available from: https://euroqol.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/EQ-5D-5L_UserGuide_2015.pdfAccessed August 27, 2015

- NaegeliANTomaszewskiELAl SawahSPsychometric validation of the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in the United StatesLupus201524131377138326038345

- WareJUser’s Manual for the SF-36v2 Health SurveySecond editionMontreal, QC, CanadaQuality Metric Inc2007

- CraigCLMarshallALSjostromMInternational physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validityMed Sci Sports Exerc20033581381139512900694

- GroenWvan der NetJLacatusuAMSerbanMHeldersPJFischerKFunctional limitations in Romanian children with haemophilia: further testing of psychometric properties of the Paediatric Haemophilia Activities ListHaemophilia2013193e116e12523374095

- van GenderenFRvan MeeterenNLvan der BomJGFunctional consequences of haemophilia in adults: the development of the Hae-mophilia Activities ListHaemophilia200410556557115357785

- DoriaASBabynPSLundinBReliability and construct validity of the compatible MRI scoring system for evaluation of haemophilic knees and ankles of haemophilic children. Expert MRI working group of the international prophylaxis study groupHaemophilia200612550351316919081

- AltmanDGPractical Statistics for Medical Research1st edChapman & Hall/CRC1990

- KosinskiMKellerSDWareJEJrHatoumHTKongSXThe SF-36 Health Survey as a generic outcome measure in clinical trials of patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: relative validity of scales in relation to clinical measures of arthritis severityMed Care1999375 SupplMS23MS3910335741

- KellerSBannCMDoddSLScheinJMendozaTRCleelandCSValidity of the brief pain inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer painClin J Pain200420530931815322437

- HarrisonMJDaviesLMBansbackNJIngramMAnisAHSymmonsDPThe validity and responsiveness of generic utility measures in rheumatoid arthritis: a reviewJ Rheumatol200835459260218278841

- HerdmanMGudexCLloydADevelopment and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L)Qual Life Res201120101727173621479777

- VelikovaGBoothLSmithABMeasuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trialJ Clin Oncol200422471472414966096