Abstract

Purpose

Many studies of persistence involving fixed dose combinations (FDCs) of cardiovascular medicines have not adequately accounted for a user’s prior experience with similar medicines. The aim of this research was to assess the effect of prior medicine experience on persistence to combination therapy.

Patients and methods

Two retrospective cohort studies were conducted in the complete Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme prescription claims dataset. Initiation and cessation rates were determined for combinations of: ezetimibe/statin; and amlodipine/statin. Initiators to combinations of these medicines between April and September 2013 were classified according to prescriptions dispensed in the prior 12 months as either: experienced to statin or calcium channel blocker (CCB); or naïve to both classes of medicines. Cohorts were stratified according to formulation initiated: FDC or separate pill combinations (SPC). Cessation of therapy over 12 months was determined using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Risk of cessation, adjusted for differences in patient characteristics was assessed using Cox proportional hazard models.

Results

There were 12,169 people who initiated combinations of ezetimibe/statin; and 26,848 initiated combinations of amlodipine/statin. A significant proportion of each cohort were naïve initiators: ezetimibe/statin cohort, 1,964 (16.1%) of whom 81.9% initiated a FDC; and amlodipine/statin cohort, 5,022 (18.7%) of whom 55.4% initiated a FDC. Naïve initiators had a significantly higher risk of ceasing therapy than experienced initiators regardless of formulation initiated: ezetimibe/statin cohort, naïve FDC versus experienced FDC HR=3.0 (95% CI 2.8, 3.3) and naïve SPC versus experienced SPC HR=4.4 (95% CI 3.8, 5.2); and amlodipine/statin cohort naïve FDC versus experienced FDC HR=2.0 (95% CI 1.8, 2.2) and naïve SPC versus experienced SPC HR=1.5 (95% CI 1.4, 1.6).

Conclusion

Prescribers are initiating people to combinations of two cardiovascular medicines without prior experience to at least one medicine in the combination. This is associated with a higher risk of ceasing therapy than when combination therapy is initiated following experience with one component medicine. The use of FDC products does not overcome this risk.

Introduction

There is good evidence to support the use of pharmacotherapies including antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medicines to reduce vascular events in at-risk patients.Citation1–Citation3 In patients who do not respond sufficiently to initial mono-therapy, the addition of a second, and sometimes third, medicine may be required to achieve target blood pressure (BP) or lipid levels. Australian guidelines suggest initiation of monotherapy for hypertension and hyperlipidemia, with a second class of medicine added subsequently if required to achieve treatment targets.Citation2,Citation4 Further to this, where fixed dose combinations (FDCs) are considered appropriate, the NPS MedicineWise guidanceCitation5 and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) restrictionsCitation6 recommend stabilization on at least one component medicine contained in the combination prior to switching to a FDC formulation.

Prescribing guidance that supports the requirement to have experience with one drug before adding a second is consistent with quality use of medicines policy in Australia.Citation7 The rationale being that individuals respond differently to medicines. For some people it may be unnecessary to start two drugs for the same risk factor, while for others who experience adverse events starting two at the same time makes it difficult to determine the causative agent.

Previous research on the use of antihypertensive medicines suggests that prescribers in Australia have not always followed local guidance in relation to initiating antihypertensive therapy.Citation8–Citation10 All three studies had investigated initial prescribing of combinations of antihypertensive agents, and found that 12.0%,Citation8 21.0%,Citation9 and 9.3%Citation10 of initiators started two or more antihypertensive medicines without prior dispensing of any antihypertensive medicines. This may be because international guidelinesCitation1,Citation11 differ to Australian guidelines for management of hypertension in that they support initiation to two antihypertensive medicines (including FDCs) in people with very high risk or markedly elevated blood pressure. The rationale being that FDCs of lower dose combinations lower blood pressure more rapidly than monotherapy, reduce side effects and are associated with higher adherence and persistence.Citation12,Citation13

Many studies that compare persistence between regimes of separate pill combinations (SPCs) and FDCs have found that FDCs are associated with longer persistence.Citation14–Citation20 However, a number of these studies have not adequately accounted for patients’ prior experience in taking medicines.Citation16–Citation20 One study considered patients’ prior experience with the actual medicines contained in the combination products but not the use of other similar-in-class medicines for the treatment of the same indication.Citation19 Because prescriber guidance suggests stabilizing patients on individual components before switching to a FDC, patients are more likely to be prescribed FDCs following experience with a single medicine or even two separate medicines. Therefore, results from persistence studies that fail to adequately account for prior experience may be biased in favor of FDCs.

There is a theoretical basis for considering that prior experience with medicines will influence medicine-taking behaviors. Health behavioral change theories suggest that patients with prior experience to similar medicines are more likely to demonstrate improved adherence and persistence with chronic medication.Citation21 In adopting new health behaviors, theories such as the transtheoretical model suggest patients progress through stages of readiness to change, before achieving sustained change, and that this process occurs over time.Citation22 Patients new to treatment do not always pass through these stages in sequence.Citation23–Citation25 Some may move back and forward through these states as they fail and re-attempt to change their behavior. This corresponds with stops and restarts in medicine-taking behaviors as individuals come to understand their disease and the need for medicines. Increased persistence over the longer term occurs when skills such as remembering to take medicines and fill prescriptions become routine habits.Citation26 The time to developing these habits may vary, but once developed habits have been found to predict subsequent persistence in experienced users of anti-hypertensives.Citation27

Because prior experience is likely to affect persistence to chronic therapies, the aim of this research was to demonstrate the size of this effect in two cohorts of patients initiating combinations of cardiovascular medicines. We conducted an analysis of two cohorts initiating combination therapies with high volume use in Australia: ezetimibe plus statin; and amlodipine plus statin.Citation28 Initiation to these combinations and therapy cessation rates were compared according to prior exposure and the formulation initiated (FDC or SPC). We hypothesized that people with prior exposure to medicines within the class would persist with therapy longer than those with no prior experience regardless of formulation.

Patients and methods

Study design and population

Two retrospective cohort studies were undertaken using the complete PBS prescription claims dataset that contains records for all Government subsidized prescriptions dispensed in Australia. The data analyzed included all dispensings for medicines supplied between April 2012 and December 2014. The PBS dataset includes patient demographics, medicine information, prescriber and dispensing information, and is described in more detail by Paige et al,Citation29 and Van Gool.Citation30 We identified two cohorts: patients supplied initial combination therapy of ezetimibe and statin; and patients supplied initial combination therapy of amlodipine and statin in the 6-month period from April to September 2013. Initiation was defined as no dispensing of the combination as either a SPC or FDC in the prior 12 months. Combination therapy was deemed to have started when both medicines were dispensed on the same day or within 30 days of each other. For the ezetimibe/statin initiators, patients were all naïve to ezetimibe, but may have filled prior statin prescriptions in keeping with the PBS restriction for use of ezetimibe as second line therapy. Initiators to amlodipine/statin may have filled either prescriptions for statins or calcium channel blockers (CCBs) prior to initiation but not both. The different inclusion criteria reflect the difference in the indications of these two combinations where ezetimibe is subsidized as second line treatment following statin therapy, and amlodipine and atorvastatin are both first line therapies for separate risk factors, ie, hypertension or heart failure and hyperlipidemia.

Each cohort was described according to prior use as: experienced if participants had received at least one prior dispensing for one class of medicine in the combination; or naïve having no dispensing of either class of medicine in the combination. Cohorts were further stratified according to formulation initiated: FDC; or SPC. All lipid-lowering and antihypertensive prescriptions for each participant were obtained for a minimum of 15 months follow-up.

The following medicines listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule according to anatomical and therapeutic chemical codes were included in this study: all lipid-lowering medicines (C10); and antihypertensive agents (C07, C08C, C08D, C08G, C09AA, C09BA, C09CA, C09DA, C09XA, C09DX, C03AA).Citation31

Ethical considerations

The design and methods for this study were approved by the Commonwealth Department of Human Services (DHS) External Request Evaluation Committee for analysis of PBS data. Additional approval to conduct these studies in the complete PBS dataset was obtained from the Department of Health. The study used de-identified data and conforms to management and release of data in accordance with the principals of the Australian Government Privacy Act, 1988.

Outcome measures

For each therapy (lipid lowering or antihypertensive) Kaplan–Meier analyses were performed over 12 months follow-up to assess the treatment duration of the first episode. Cessation to therapy was defined as a break of 60 days or more following exhaustion of the supply in the last dispensing for any lipid-lowering or antihypertensive medicines. PBS prescription durations were assigned as 30 days for all statins and 28 days for anti-hypertensives. This assumption was based on the 75th percentile for prescription refills for each medicine in the dataset. The 75th percentile also correlated well with the number of daily doses dispensed in a standard PBS prescription for most of these medicines. Length of treatment to any lipid-lowering therapy in the ezetimibe and statin cohort included time from initiation to cessation of all lipid-lowering medicines. For the amlodipine and statin cohort the length of treatment was the shorter duration of the two, ie, when combination antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapy was ceased. All patients in each cohort had a minimum of 15 months follow-up and censoring occurred at study end where supply of prescriptions fell within the last 3 months.

A second Kaplan–Meier analysis was conducted where patients who received only one dispensing of either therapy were removed from the cohorts. This analysis included only those patients demonstrating “early stage” persistence to both therapies,Citation32 and was conducted because cessation following the dispensing of the first prescription is likely to be in response to adverse effects which could bias results against naïve initiators.

Statistical analysis

The following baseline characteristics were determined at the time patients initiated combination therapy (index date): age; gender; concession status (concessional or general beneficiary); prescriber type (specialist physician or general practitioner); patients qualifying for the PBS safety-net in the 6 months either side of index date; the number of co-dispensed PBS medicines (co-dispensing is defined as the overlap of supply of PBS medicine[s] within the 75th percentile refill interval for each medicine); the number of comorbidities based on RxRisk-V index and medicines co-dispensed on index date.Citation33 These patient characteristics were compared using chi square for differences in proportions and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for variables not normally distributed. Cox regression was used to model time to cessation of therapy between naïve and experienced user cohorts. Patient characteristics that differed between the two cohorts and considered potential confounders were included (stepwise) in the Cox proportional hazards models. The proportional hazard assumption was checked by visual assessment of graphs plotting the log of the negative log of the estimated survivor function against log. All analyses were conducted in SAS Enterprise Guide version 5.1.

Results

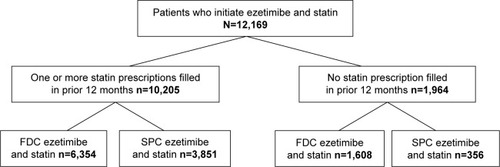

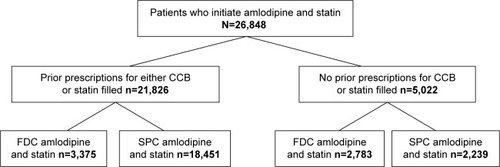

Overall, 12,169 people initiated combinations of ezetimibe/statin and 26,848 initiated combinations of amlodipine/statin. A significant proportion initiated these combinations naïve to either class of medicine: within the ezetimibe/statin cohort 1,964 (16.1%) were naïve users, of whom 81.9% initiated a FDC; and within the amlodipine/statin cohort 5,022 (18.7%) were naïve users, of whom 55.4% initiated the FDC ( and ).

Figure 1 Patient flow diagram for Cohort 1: ezetimibe and statin users.

Figure 2 Patient flow diagram for Cohort 2: amlodipine and statin users.

Naïve initiators in both cohorts were younger, had fewer comorbidities and fewer co-dispensed medicines, and were more likely to have their initial combination medicines prescribed by a general practitioner ().

Table 1 Patient characteristics of included study population: ezetimibe and statin (A) and amlodipine and statin (B)

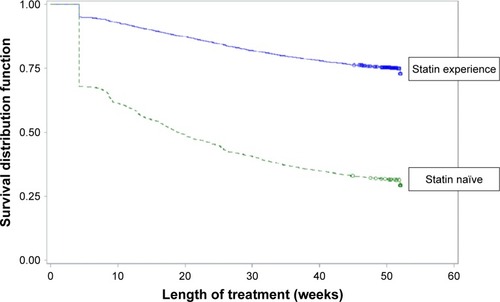

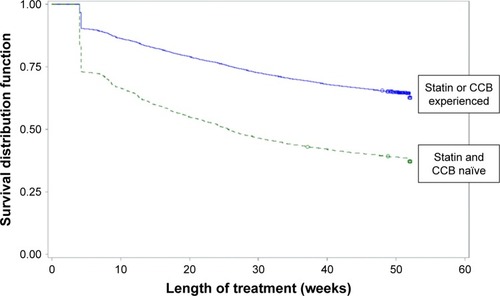

In the amlodipine/statin and ezetimibe/statin cohorts, cessation rates were significantly higher in those who initiated therapy naïve to both classes of medicines ( and ). Following adjustment for the different characteristics of the naïve and experienced populations, naïve initiators to combinations of amlodipine/statin and ezetimibe/statin were 1.6 and 3.3 times more likely (respectively) to cease therapy during the first 12 months of treatment (). The second persistence analysis, where patients who filled only one prescription at initiation of combination therapy were removed, confirmed these results; cessation rates remained significantly higher in naïve initiators in both the ezetimibe/statin and amlodipine/statin cohorts.

Figure 3 Kaplan–Meier survival curves for persistence to any lipid-lowering therapy following initiation to combination ezetimibe and statin.

Figure 4 Kaplan–Meier survival curves for persistence to antihypertensive and statin therapy following initiation to combination amlodipine and statin.

Table 2 Cessation rates and risk of cessation of therapy 12 months post initiation to combination therapy

When the two cohorts were stratified according to formulation initiated, all naïve initiators had significantly higher cessation rates compared to the corresponding experienced cohort regardless of whether a FDC or SPC was initiated (). Cessation rates at 12 months in naïve initiators of both formulations ranged from 60.4% to 69.0% and for experienced initiators, the cessation rates ranged from 19.5% to 38.0%.

Table 3 Cessation rates post initiation to combination therapy and risk of cessation at 12 months according to formulation initiated

Discussion

This study, which included the analysis of two separate cohorts, found that a significant number of people commenced combination lipid-lowering therapy or combination statin and anti-hypertensive who were naïve to both medicines. According to the PBS restrictions,Citation34 the majority of the population eligible for combination ezetimibe/statin therapy should have at least trialed statin monotherapy before adding ezetimibe. Only a very small number of people, approximately 1/160,000 peopleCitation35 with homozygous hypercholesterolemia were eligible to initiate combination ezetimibe/statin without prior experience to statin therapy. Our results raise the concern that many naïve initiators to ezetimibe/statin combinations may not be treated optimally with a statin and potentially prescribed ezetimibe unnecessarily.

Both the FDC and SPC formulations of amlodipine and statin medicines are registered in Australia for first line pharmacotherapy, however prescribing guidanceCitation5 and the PBS restrictionCitation36 recommend initiation of amlodipine and atorvastatin FDC after trialing a separate pill anti-hypertensive, ideally a CCB. Contrary to this restriction for subsidy, 18.7% of people initiating this combination had no dispensing of a CCB or statin in the prior 12 months.

As hypothesized, persistence to therapy was greater in those with prior experience of a medicine in class than in naïve users. Our results confirmed this and demonstrate the large effect prior experience can have on measures of persistence and therefore its potential to bias results in studies comparing this outcome. We found that those initiating either combination therapy as naïve users were younger and less likely to be concession card holders than those who initiated combinations experienced to one of the medicines within the class. Younger age and higher prescription costs have been associated with higher cessation rates in other studies of persistence to antihypertensive and statin therapy.Citation37–Citation39 We also found that naïve initiators were more commonly prescribed FDCs than SPCs. While the reasons that practitioners more frequently prescribe FDCs to naïve users are unknown; prescribers may assume FDCs will improve persistence in at-risk populations who are new to treatment. However, our results do not support this assumption because cessation rates in both FDC and SPC naïve initiators were similar and significantly higher than experienced initiators across both cohorts.

PBS data does not include information on adverse events therefore it is not possible to determine the reason why patients cease filling prescriptions and the extent to which adverse events contributed to cessation rates. To approximate the effect of adverse events we conducted a second persistence analysis where patients who filled only one prescription were excluded. This resulted in lower cessation rates in both cohorts. Despite this improvement, a significant gap between cessation rates of naïve and experienced users remained, indicating that adverse events only partially explained the difference. There may also be psychological reasons that explain the higher cessation rates in those naïve to combination therapy.Citation40,Citation41 As discussed in the introduction, behavior change theories predict that it takes time and practice to achieve persistence to therapy.Citation22 Lack of opportunity to develop routine medicine-taking habits is likely to be a factor influencing the high cessation rates found in naïve initiators in these two cohorts.

The results of this study support current Australian prescribing guidance that promotes starting one new medicine at a time where clinically possible. Persistence may also be improved if patients new to chronic therapies are encouraged to link medicine taking to other daily routines to support habit forming behavior.Citation27

The strengths of this study were the measurement of persistence to combinations of cardiovascular medicines in the entire PBS population. The PBS dataset included under co-payment prescriptions for general beneficiaries, providing almost complete capture of medicine use in the Australian population since April 2012. Two possible exceptions are medicines supplied as industry samples or as private prescriptions. The retrospective study design also meant that patients’ medicine-taking behavior was not affected by researcher contact, a potential source of bias in persistence studies that involve researcher or health professional and patient interactions.Citation42 As the PBS dataset is complete from April 2012 onwards, we were limited to a 12-month look back period to determine prior use of similar in-class medicines. This may have slightly overestimated the proportion of naïve users, as a longer look back period of 2 or 3 years may have identified more people with prior exposure to these medicines, however, this would bias our results towards the null, given experienced users had longer persistence rates.

Other limitations of the PBS dataset are the lack of information on diagnosis, severity of illness and date of death. Not censoring for death is unlikely to significantly impact results as the average age was 56–69, and follow-up limited to 12 months. Finally, prescriber data are not linked to PBS data, therefore the extent of primary non-persistence (patients who don’t fill any prescriptions) was not captured in this study and the direction of this potential bias between experienced and naïve users is unknown.

Conclusion

This study found that almost one in five new users of combination cardiovascular therapies initiate two medicines together, and that these patients were at higher risk of ceasing therapy in the first 12 months of treatment compared to those who had been using at least one medicine within the class. We also found the use of FDCs was more common than SPCs in naïve initiators to combination therapy but that FDC formulations did not reduce the risk of ceasing therapy. Prescribers need to consider the higher risk of treatment cessation in new users regardless of formulation initiated and consider starting new medicines incrementally where possible.

Author contributions

Louise E Bartlett designed the research, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. Elizabeth E Roughead and Nicole Pratt contributed to the research design, data analysis, interpretation, critical review and revision of the final manuscript. All authors have approved this version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgments

All authors have completed the unified competing interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi-disclosure (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare this work was supported by an Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) centre for research excellence in post-marketing surveillance of medicines and devices grant (GNT1040938).

Disclosure

Louise E Bartlett is a part-time employee of the Commonwealth Department of Health. Elizabeth E Roughead is supported by an NHMRC Fellowship (GNT1110139). Nicole Pratt is supported by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (Grant Number GNT1035889). The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PiepoliMFHoesAWAgewallS2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: the Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts). Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR)Eur Heart J201637292315238127222591

- National Vascular Disease Prevention AllianceGuidelines for the Management of Absolute Cardiovascular Disease RiskCanberra AustraliaNational Stroke Foundation2012 Available from: https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/images/uploads/publications/Absolute-CVD-Risk-Full-Guidelines.pdfAccessed January 28, 2018

- JamesPAOparilSCarterBL2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (jnc 8)JAMA2014311550752024352797

- National Heart Foundation of AustraliaGuideline for the diagnosis and management of hypertension in adultsMelbourneNational Heart Foundation of Australia2016 Available from: http://heartfoundation.org.au/for-professionals/clinical-information/hypertensionAccessed January 28, 2018

- NPS MedicinewiseKey points on fixed dose combination medicines: NPS Medicinewise2013 [updated 20 Dec 2013]. Available from: http://www.nps.org.au/topics/combination-medicines/for-health-professionals/key-pointsAccessed January 28, 2018

- Commonwealth Department of HealthPharmaceutical Benefits Schedule pbs.gov.au2016 Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/medicine/item/9373HAccessed January 28, 2018

- Commonwealth Department of Health and AgeingNational Medicines PolicyCanberra ACTCommonwealth Government2000 Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/national-medicines-policyAccessed January 28, 2018

- GadzhanovaSIlomäkiJRougheadEEAntihypertensive use before and after initiation of fixed-dose combination products in Australia: a retrospective studyInt J Clin Pharm201335461362023677815

- GadzhanovaSRougheadEEBartlettLELong-term persistence to mono and combination therapies with angiotensin converting enzymes and angiotensin II receptor blockers in AustraliaEur J Clin Pharmacol201672676577126961086

- SchafferALPearsonS-ABuckleyNAHow does prescribing for antihypertensive products stack up against guideline recommendations? An Australian population-based study (2006–2014)Br J Clin Pharmacol20168241134114527302475

- LeungAANerenbergKDaskalopoulouSSHypertension Canada’s 2016 Canadian Hypertension Education Program Guidelines for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertensionCan J Cardiol201632556958827118291

- DüsingRThe case for single pill combinationsCurr Med Res Opin201430122423242425222763

- BangaloreSLeyLImproving treatment adherence to antihypertensive therapy: the role of single-pill combinationsExpert Opin Pharmacother201213334535522220825

- BaserOAndrewsLMWangLXieLComparison of real-world adherence, healthcare resource utilization and costs for newly initiated valsartan/amlodipine single-pill combination versus angiotensin receptor blocker/calcium channel blocker free-combination therapyJ Med Econ201114557658321728914

- ZengFPatelBVAndrewsLFrech-TamasFRudolphAEAdherence and persistence of single-pill ARB/CCB combination therapy compared to multiple-pill ARB/CCB regimensCurr Med Res Opin201026122877288721067459

- PatelBVScott LeslieRThiebaudPAdherence with single-pill amlodipine/atorvastatin vs a two-pill regimenVasc Health Risk Manag20084367368118827917

- PanjabiSLaceyMBancroftTCaoFTreatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and economics of triple-drug therapy in hypertensive patientsJ Am Soc Hypertens201371466023321404

- SimonsLAOrtizMCalcinoGPersistence with a single pill versus two pills of amlodipine and atorvastatin: the Australian experience, 2006–2010Med J Aust2011195313413721806531

- XieLFrech-TamasFMarrettEBaserOA medication adherence and persistence comparison of hypertensive patients treated with single-, double- and triple-pill combination therapyCurr Med Res Opin201430122415242225222764

- MachnickiGOngSHChenWWeiZJKahlerKHComparison of amlodipine/valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide single pill combination and free combination: adherence, persistence, healthcare utilization and costsCurr Med Res Opin201531122287229626397178

- HolmesEAFHughesDAMorrisonVLPredicting adherence to medications using health psychology theories: a systematic review of 20 years of empirical researchValue Health201417886387625498782

- ProchaskaJOTranstheoretical model of behavior changeGellmanMDTurnerJREncyclopedia of Behavioral MedicineNew York, NYSpringer201319972000

- MunroSLewinSSwartTVolminkJA review of health behaviour theories: how useful are these for developing interventions to promote long-term medication adherence for TB and HIV/AIDS?BMC Public Health2007710417561997

- World Health OrganizationAdherence to Long Term Therapies: Evidence for ActionGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2003 Contract No.: ISBN 92 4 154599 2

- BrawleyLRCulos-ReedSNStudying adherence to therapeutic regimensControl Clin Trials2000215 SupplS156S163

- ReachGRole of habit in adherence to medical treatmentDiabet Med200522441542015787666

- Alison PhillipsLLeventhalHLeventhalEAAssessing theoretical predictors of long-term medication adherence: patients’ treatment-related beliefs, experiential feedback and habit developmentPsychol Health201328101135115123627524

- PBS Information Management Section PPBPBS Expenditure and Prescriptions twelve months to 30 June 2015Health DoCanberra ACT pbs.gov.au2015 Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/statistics/pbs-expenditure-prescriptions-30-june-2015Accessed April 10, 2018

- PaigeEKemp-CaseyAKordaRBanksEUsing Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme data for pharmacoepidemiological research: challenges and approachesPublic Health Res Pract2015254e254154626536508

- Van GoolKParkinsonBKennyPMedicare Australia data for research: an introductionCentre for Health Economic Research and Evaluation UoTS2011 updated 2015 Available from: http://www.crest.uts.edu.au/pdfs/Factsheet-Medicare-Australia-UpdatedNov2015.pdfAccessed January 28, 2018

- World Health OrganizationATC Structure and PrinciplesOslo, NorwayNorwegian Institute of Public Health2009 Available from: https://www.whocc.no/atc/structureAccessed April 10, 2018

- RaebelMAPSchmittdielJPKarterAJPKoniecznyJLPSteinerJFStandardizing terminology and definitions of medication adherence and persistence in research employing electronic databasesMed Care2013518 Suppl 3S11S2123774515

- VitryAWongSARougheadEERamsayEBarrattJValidity of medication based co-morbidity indices in the Australian elderly populationAust N Z J Public Health2009332128130

- Commonwealth Department of Healthezetimibe + simvastatin item 9484E pbs.gov.au Department of Health2016 [updated October 2016]. Available from: https://www.pbs.gov.au/medicine/item/9484EAccessed January 28, 2018

- BaumSJSijbrandsEJGMataPWattsGFThe doctor’s dilemma: challenges in the diagnosis and care of homozygous familial hypercholesterolemiaJ Clin Lipidol20148654254925499935

- Commonwealth Department of Healthamlodipine + atorvastatin item 9055N pbs.gov.au Department of Health2016 Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/medicine/item/9055NAccessed January 28, 2018

- QvarnströmMKahanTKeilerHPersistence to antihypertensive drug treatment in Swedish primary healthcareEur J Clin Pharmacol201369111955196423857249

- PoluzziEStrahinjaPVaccheriAAdherence to chronic cardiovascular therapies: persistence over the years and dose coverageBr J Clin Pharmacol200763334635517096681

- KnottRJPetrieDJHeeleyELChalmersJPClarkePMThe effects of reduced copayments on discontinuation and adherence failure to statin medication in AustraliaHealth Policy2015119562062725724823

- KronishIMYeSAdherence to Cardiovascular medications: lessons learned and future directionsProgr Cardiovasc Dis2013556590600

- BerglundELytsyPWesterlingRAdherence to and beliefs in lipid-lowering medical treatments: a structural equation modeling approach including the necessity-concern frameworkPatient Educat Couns2013911105112

- LamWYFrescoPMedication adherence measures: an overviewBioMed Res Int2015201521704726539470