Abstract

Background

Patient preferences are important to consider in the decision-making process for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. Vulnerable populations, such as racial/ethnic minorities and low-income, veteran, and rural populations, exhibit lower screening uptake. This systematic review summarizes the existing literature on vulnerable patient populations’ preferences regarding CRC screening.

Methods

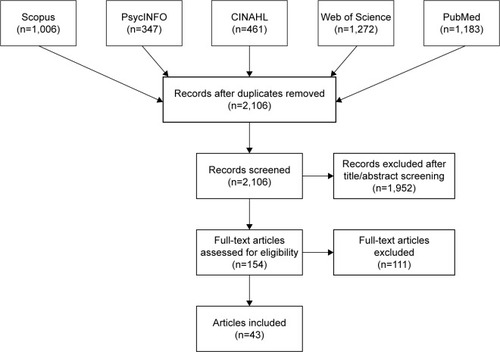

We searched the CINAHL, PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases for articles published between January 1, 1996 and December 31, 2017. We screened studies for eligibility and systematically abstracted and compared study designs and outcomes.

Results

A total of 43 articles met the inclusion criteria, out of 2,106 articles found in our search. These 43 articles were organized by the primary sub-population(s) whose preferences were reported: 27 report on preferences among racial/ethnic minorities, eight among low-income groups, six among veterans, and two among rural populations. The majority of studies (n=34) focused on preferences related to test modality. No single test modality was overwhelmingly supported by all sub-populations, although veterans seemed to prefer colonoscopy. Test attributes such as accuracy, sensitivity, cost, and convenience were also noted as important features. Furthermore, a preference for shared decision-making between vulnerable patients and providers was found.

Conclusion

The heterogeneity in study design, populations, and outcomes of the selected studies revealed a wide spectrum of CRC screening preferences within vulnerable populations. More decision aids and discrete choice experiments that focus on vulnerable populations are needed to gain a more nuanced understanding of how vulnerable populations weigh particular features of screening methods. Improved CRC screening rates may be achieved through the alignment of vulnerable populations’ preferences with screening program design and provider practices. Collaborative decision-making between providers and vulnerable patients in preventive care decisions may also be important.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common type of cancer and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the US. In 2017, there were an estimated 135,430 new cases diagnosed and 50,260 CRC-specific deaths nationally.Citation1 Annually, CRC costs the US healthcare system approximately $14 billion.Citation2 Screening has been shown to reduce CRC incidence and mortality by 30%–60% and has the potential to save an estimated 18,800 lives per year.Citation3,Citation4 Since early stage CRC is asymptomatic, screening is especially important for early detection and appropriate treatment.Citation5 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended screening using colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, or fecal testing, such as fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) and fecal immunochemical testing (FIT), at appropriate intervals (eg, colonoscopy every 10 years, sigmoidoscopy every 5 years, fecal testing annually), for average-risk adults aged 50–75 years.Citation6 Colonoscopy and fecal testing are the most commonly used modalities in the US.Citation7

The US has seen an increase in CRC screening over time, yet the 2015 national rate of 62.6% is well below the Healthy People 2020 target of 70.5% set by the US Department of Health and Human Services.Citation8,Citation9 CRC screening rates are particularly low within many vulnerable sub-populations, including racial and ethnic minorities and foreign-born, low-income, publicly insured, uninsured, veteran, disabled, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (LGBTQ), and rural populations.Citation10–Citation15 Lack of consideration of patient preferences is one of several factors contributing to lower screening rates.Citation16 To improve uptake, communication between providers and patients about decision alternatives, preferences, and risk–benefit tradeoffs is important.Citation17 Shared decision-making, in which the provider and patient work together to agree upon an optimal decision, has been increasingly recommended for screening.Citation18 Considerations for CRC screening include test characteristics, such as accuracy, invasiveness, and comfort, and delivery characteristics, including cost, convenience, and ease of access.Citation19 For example, some patients may prefer fecal testing, due to its noninvasive nature and low cost. Presenting choices that match individuals’ preferences may increase CRC screening uptake.

Systematic reviews have previously assessed CRC screening preferences within the general population and found that while accuracy and clinical effectiveness are valued, there is not an overwhelming preference for a single modality.Citation20–Citation22 Given that vulnerable populations screen at lower rates and face greater barriers to preventive care, their CRC screening preferences may differ in important ways.Citation23–Citation27 Thus, a better understanding of preferences among vulnerable populations is needed to inform interventions and policies that aim to increase their CRC screening rates. To do this, we conducted a systematic review with the objective of capturing the preferences of vulnerable populations with respect to CRC screening. We aimed to capture all aspects of preference in the context of screening, such as modality, test attributes, and program features. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to address CRC screening preferences specifically among vulnerable patients.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.Citation28 We adapted the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Time (PICOT) framework, adding in both study setting and design, to identify the studies of interest in this review.Citation29 Since the PICOT framework is often used in the context of eliciting the effect of a treatment, and we were interested in reviewing a wide range of study types, some of which did not include a specific intervention, we omitted the intervention component of the framework. outlines the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this review based on the adapted PICOT framework.

Table 1 Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We focus our review on vulnerable populations who experience widely observed health disparities and are at risk for poor quality of care and poor health outcomes due to non-clinical, discriminatory, and marginalizing factors.Citation30–Citation34 The National Academy of Medicine (formerly Institute of Medicine) and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality have, for decades, placed elimination of health disparities at the center of healthcare quality initiatives, noting that high-quality care should not be differentially received by people because of race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual preference, geography, or socioeconomic status.Citation35–Citation38 The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Minority Health describes a health disparity as “a particular type of health difference that is closely linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage.”Citation30,Citation39 HHS characterizes underserved, vulnerable, and special need populations as communities that include members of minority populations or individuals who have experienced health disparities, specifically Latinos, African Americans, American Indians/Alaska Natives, refugees/migrants, individuals with Limited English Proficiency (LEP), uninsured, low-income, rural, LGBT, and disabled people, including disabled veterans, as well as pregnant women and children.Citation39,Citation40 We adopt this inclusive definition of “vulnerable and medically underserved” populations in our review, excluding pregnant women and children, who are not age-eligible for CRC screening and therefore not relevant to this review.

Since little was known about the literature addressing vulnerable patients’ CRC screening preferences, including the types of preferences assessed, we attempted to cast a wide net on this topic. We included all articles that met our review criteria with a variety of study designs (eg, observational and experimental) because our goal was to understand vulnerable patients’ preferences about CRC screening generally. That is to say, we did not constrain our review to specific aspects of preferences, such as preference tradeoffs or changes in preference as a result of experimental intervention; both of these types of articles were viewed as relevant and within scope.

We searched the PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Web of Science databases for articles published from January 1, 1996 to December 31, 2017 (). We selected this timeframe because the USPSTF released its first CRC screening guidelines in December 1995.Citation41 The following search string was used to identify relevant articles: ((“colorectal” AND “cancer” OR “colon” AND “cancer”) AND (“screening” OR “detection” OR “testing” OR “test”) AND ((“preference” OR “preferences” OR “perception” OR “perceptions”) OR (“discrete” AND “choice”) OR (discrete AND choices))) AND PUBYEAR >1995.

Since our goal was to capture a range of vulnerable populations, we did not list the particular populations of interest, as identified in , in this initial search string. This strategy allowed us to discern whether vulnerable populations were included in each article rather than exclude studies outright that failed to mention a specific term that we associated with “vulnerable” or “underserved.” Studies from the US and other developed country contexts that comprised subgroup analyses regarding screening preferences for one or more vulnerable populations were eligible for inclusion.

In total, 4,269 articles were initially identified and imported into F1000 Workspace (Faculty of 1000 Ltd, 2018), a reference management database. After duplicates were removed, 2,106 articles were transferred to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation Ltd, 2018) to be screened.

Using Covidence, two reviewers (SL and MO) independently screened the titles and abstracts of the articles for patient-level studies focused on CRC screening. The reviewers began with a small pool of 20 articles to ensure consistency and to refine the inclusion/exclusion criteria. These reviewers resolved any discrepancies in their ratings and, when a consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer (SW) assessed the article and made the final decision. These same procedures were then used to review the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles. In this initial phase, we excluded articles that were not related to CRC screening, such as studies about other health conditions, CRC studies regarding treatment, survivorship, or genetics, and non-patient-level CRC studies (eg, provider-only interventions). This strategy provided the opportunity to review the full-text of CRC screening studies to consider if a sub-population analysis was included and if a preference-related outcome was measured, even if the larger objective of the article was not specific to these areas. During the title/abstract screening process, 1,952 articles were removed, leaving 154 full-text articles to be reviewed.

During the full-text review, the reviewers assessed whether each article should be included or excluded according to the criteria outlined in and categorized the excluded articles by reason for exclusion. Discrepancies regarding whether the article should be included or excluded, as well as the reason for exclusion, were resolved by the two reviewers (SL and MO) with the third reviewer (SW) making the final decision about any remaining discrepancies. Of the 154 full-text articles, 111 were excluded, most commonly because they did not provide a subgroup analysis for a vulnerable population (n=70). The other primary reasons for exclusion were outcomes outside the scope of this analysis, such as the reporting of screening behaviors without addressing patient preferences (n=20), the wrong study design including systematic and literature reviews (n=16), duplicate studies (n=3), non-English publications (n=1), and publication dates outside the study window (n=1).

The two reviewers abstracted the data from the included articles into a literature matrix using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). The literature matrix included more than 20 structured fields such as title, study design, US or international study, sub-population studied, total sample size and the sample size of the vulnerable patients, baseline population characteristics (eg, age, sex, race), outcome measure, and findings. For the studies in which an intervention was implemented, we also reported the type of intervention, mode of delivery, and who conducted the intervention. Given the number of metrics and heterogeneity across studies, in this paper we report the primary type of vulnerable population included in each article, study objective, study design, sample sizes of the total and vulnerable populations, outcome measured, and findings to provide an understanding of the breadth of research currently available on vulnerable patients’ preferences.

Results

A total of 43 articles that addressed patient preferences regarding CRC screening among vulnerable groups are included in this systematic review. The selected articles are organized by the types of vulnerable population(s) whose preferences are reported. Of these studies, 27 reported preferences among racial/ethnic minorities, eight among low-income groups, six among veterans, and two among rural populations. Notably, many studies elicited preferences from more than one underserved population, since these categories are not necessarily mutually exclusive. For example, studies often included racial or ethnic minorities as well as low-income individuals. In this analysis, studies were categorized based on the vulnerable population prioritized during sampling and analysis.

Grouping by outcomes or study design, rather than sub-population of interest, was considered, but we ultimately decided that categorizing by sub-population would better assist public health practitioners and researchers in designing interventions for these specific sub-groups. However, within each section, we organized the study results by outcome. Of the 43 studies, 34 measured preference in terms of modality, displaying a marked tendency to focus on modality rather than other aspects of preference within research; 23 measured preference in terms of test attributes. The other types of preferences assessed were source of information (n=2), type of decision-making (n=2), program delivery (n=2), expert recommendation (n=1), willingness to pay (WTP; n=1), and provider characteristics (n=1).

Racial/ethnic minorities (n=27)

Twenty-seven articles reported CRC screening preferences for a single or multiple racial/ethnic minority groups ().Citation42–Citation68 Out of these studies, nine were conducted among African Americans,42,44,48,49,54,57–59,61 five among Hispanics/Latinos,Citation47,Citation53,Citation55,Citation62,Citation68 eight among both African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos,Citation43,Citation45,Citation50,Citation51,Citation63–Citation66 four among non-whites,Citation46,Citation56,Citation60,Citation67 and one among Korean Americans.Citation52 Race was self-reported in nearly all of these articles, except for a study in which recruitment was conducted at a community-based organization serving Korean Americans,Citation52 a study that used health insurance claims data with enrollment database-reported race/ethnicity,Citation59 and a study that did not clearly specify how race/ethnicity was obtained.Citation63 In terms of outcomes, 22 studies reported preferences in terms of test modality and/or specific test attributes.Citation42–Citation46,Citation48–Citation51,Citation53,Citation56–Citation67 Of the remaining five articles, two examined preferences regarding shared decision-making,Citation54,Citation55 two investigated preferred sources of information,Citation47,Citation52 and one considered preference for the sex and ethnicity of endoscopists.Citation68

Table 2 Characteristics of studies with racial/ethnic minorities

Screening modality

There was a significant variation in the preferred screening modality within the studies primarily focused on minority racial and ethnic groups. Five papers reported colonoscopy as the preferred test, six studies reported fecal testing as the preferred screening method, four studies found mixed or inconclusive results, and five studies found that race/ethnicity was not associated with preferred modality. Of those who reported colonoscopy as the preferred test, four focused on African Americans only,Citation48,Citation57,Citation58,Citation61 and one included both African Americans and Hispanics.Citation45 Of the six studies that reported fecal testing as the preferred screening method, two studies reported a preference for home-based fecal tests over colonoscopy among multiracial/multiethnic groups,Citation43,Citation67 one study reported a preference specifically for FOBT among minority racial groups,Citation46 one study reported a preference specifically for FIT among African Americans,Citation49 and two studies, one among African AmericansCitation42 and one among a non-white study populationCitation60 identified stool-based DNA testing as the preferred option. Finally, of the five studies that found that race/ethnicity was not associated with preferred test modalities, four found colonoscopy as the preferred screening test in the general population;Citation44,Citation50,Citation56,Citation59 the remaining study found that FOBT was preferred over colonoscopy in the general population.Citation66

Test attributes

Nine articles reported attributes that racial and ethnic minority patients value in particular CRC screening tests or programs.Citation42,Citation45,Citation51,Citation53,Citation57,Citation61,Citation63,Citation65,Citation66 Test accuracy was commonly reported as an important attribute, regardless of the preferred test or particular group.Citation42,Citation45,Citation51,Citation57,Citation61,Citation63 For example, although Hawley et al found differences in the preferred modality between African Americans, Hispanics, and whites, accuracy was rated as the most important attribute across all groups.Citation51 Accuracy was also an influential factor among African Americans who preferred sDNA,Citation42 as well as African Americans who preferred colonoscopy.Citation61 Palmer et al reported that accuracy and thoroughness were the most positive attributes of colonoscopy, while test ease and non-invasiveness were viewed as the best attributes of FOBT for African Americans.Citation57 Similarly, Chablani et al found that the most preferred attribute of colonoscopy is test accuracy, whereas the top attribute of Cologuard is the lack of preparation needed, in a sample of African Americans and Hispanics.Citation45 Among African Americans, Hispanics/Latinos, and whites who prefer FOBT, convenience was identified as the most important attribute.Citation66 A discrete choice experiment conducted among Latinos determined that patients in the study were more concerned about the costs of screening and any required follow-up care than the type of modality used or the amount of time required for travel.Citation52

This review also highlighted some differences in perceptions regarding test attributes between racial and ethnic groups. Although African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos both ranked accuracy and comprehensiveness of the test as two of the most important features, African Americans were also concerned about discomfort and potential complications, while Hispanics/Latinos focused on the extent of scientific evidence available.Citation63 African Americans were more likely to be embarrassed by stool-based DNA testing than whites,Citation42 and less likely to associate low cost with SEPT9 blood testing, and to consider the frequency of each test as important to decision-making, compared to whites and Hispanics/Latinos.Citation51,Citation63

Source of information

Two articles addressed minority patients’ preferences for their source of information regarding CRC screening.Citation47,Citation52 Jo et al conducted interviews among Korean Americans and determined that study participants had the strongest desire to learn from an educational session, followed by the Korean media and print materials.Citation52 In surveys with Hispanic/Latino patients, Ellison et al found that the preferred sources of information included providers, health brochures, television, and someone who speaks the same language.Citation47 Therefore, there is evidence to suggest that ethnic minority patients look to cultural sources for resources related to preventive care.

Decision-making process

The two articles that studied decision-making preferences indicated the importance of shared decision-making for CRC screening among African AmericansCitation54 and Hispanics/Latinos.Citation55 For example, Molokwu et al found that over half of the Hispanic/Latino participants preferred a collaborative role, rather than a passive or active role, in the decision-making process.Citation55 Similarly, Messina et al determined that African Americans, as compared to whites, would rather engage in shared decision-making than make CRC screening decisions independently.Citation54

Provider demographics

Zapatier et al found that Hispanics overall exhibited a preference for the sex and ethnicity of endoscopist.Citation68 In particular, Hispanic women prefer to have a female endoscopist and Hispanics regardless of sex prefer to have an endoscopist who is also Hispanic.Citation68

Low-income populations (n=8)

Eight articles reported CRC screening preferences among low-income populations ().Citation69–Citation76 Six of these studies were conducted in an international setting,Citation69,Citation70,Citation72–Citation75 and two were conducted domestically.Citation71,Citation76 Four studies reported monthly incomes,Citation69,Citation72,Citation74,Citation75 two studies reported annual incomes,Citation70,Citation76 one study used social grade as a proxy for socioeconomic status,Citation73 and one study only included participants with an annual household income <150% of the federal poverty level (FPL).Citation71 Since the studies were conducted in different settings, most did not use a standardized threshold for defining low income, such as a percentage of the FPL. With the exception of Quick et al,Citation71 we instead included studies that provided a subgroup analysis by income or social grade and focused on the results for the lowest income or social grade category.

Table 3 Characteristics of studies with low-income populations

Six of the eight studies focused on preference of FIT over colonoscopy,Citation69,Citation71,Citation72,Citation74–Citation76 while the other two studies focused on WTPCitation70 and preference for an expert recommendation.Citation73 In the WTP study, Frew et al found that low-income patients had lower WTP values for CRC screening and higher-income patients had higher WTP values.Citation70 Quick et al pointed to a possible relationship between lower income and colonoscopy preference.Citation71 Yet, Wong et al showed that low-income participants were more likely to shift preference from colonoscopy to FIT after an educational session,Citation75 and two other studies found higher income to be associated with colonoscopy preference.Citation69,Citation76 In contrast, Saengow et al and Wong et al did not find any association between income and preference,Citation72,Citation74 and Waller et al did not find an association between lower social grade and preference for expert recommendation.Citation73

Veterans (n=6)

Six studies sampled patients exclusively from the US Veterans Health Administration, and all focused on modality preferences ().Citation77–Citation82 Four of these studies indicated that colonoscopy was the preferred modality among veterans.Citation77–Citation79,Citation81 Rajapaksa et al found that the preference for computed tomographic colonography (CTC) vs colonoscopy was not significantly different.Citation82 This study also found that racial/ethnic minorities among the veteran population were less likely to prefer CTC over colonoscopy.Citation82 Moawad et al is the only study that suggested that colonoscopy is not the preferred modality among veterans; rather, in this study, veterans preferred CTC.Citation80

Table 4 Characteristics of studies with veteran populations

Rural (n=2)

Two studies focused primarily on US rural populations’ preferences for CRC screening ().Citation83,Citation84 Pham et al studied a rural population that consisted of predominantly Hispanics, but a subgroup analysis to see whether preference varied by race was not conducted.Citation83 This study assessed delivery attributes of different fecal test options and found that participants prefer tests that use probes and vials, require a single stool sample, and provide clear, visual instructions.Citation83

Table 5 Characteristics of studies with rural populations

Pignone et al sampled from a rural setting and included a large percentage of uninsured and low-income individuals.Citation84 This study assessed preferences for four screening program delivery attributes (testing options available, travel time, money received for completing screening, and out-of-pocket follow-up care costs). Pignone et al showed that screening costs and follow-up costs are more important factors in rural patients’ preferences than travel time and specific test modality and that participants value having the option of fecal testing, rather than only being offered colonoscopy.Citation84

Discussion

This review provides insight into the current literature regarding the CRC screening preferences of vulnerable populations. This information can be used to strengthen targeted interventions and policies seeking to address their relatively low screening rates. We found that there is not a single preferred CRC screening test across the identified vulnerable populations. Instead, these studies highlighted opportunities to better engage diverse patients in their preventive care decisions. These opportunities include facilitating a collaborative decision-making process regarding the type of modality used and eliciting individual patients’ preferences about particular tests, for example, through a decision aid approach. The results demonstrate that efforts to promote CRC screening should address the wide range of testing modality options, since there is much variation in individual preferences.

A relatively large number of studies addressed CRC screening preferences among vulnerable patient populations (n=43); of these, seven studies were conducted in non-US developed countries. Most studies investigated the preferences of racial and ethnic minority groups, with few studies that focused on rural populations or immigrants. This is concerning, since the US comprises large swaths of rural areas and a growing immigrant population, making rural and immigrant groups important populations to consider.Citation85,Citation86 Many studies, especially those that focused on Hispanic/Latinos, may have captured immigrant populations, but did not always record immigrant status. Likewise, while some studies included participants who were vulnerable in terms of insurance status (eg, Medicaid enrollees, the uninsured), these studies focused on preferences among a different population, such as racial or ethnic minorities or low-income populations. Notably, there have yet to be studies assessing preferences in two vulnerable populations identified in our inclusion criteria: individuals with disabilities and members of the LGBTQ community.

In terms of outcomes, most studies across vulnerable groups focused on preferences for test modality, most commonly contrasting colonoscopy and fecal testing. The high density of studies concentrating on modality points to the dearth of studies that measured test attribute, program features, how providers should approach CRC screening discussions, and other aspects of preference. There was relatively strong agreement regarding a preference for colonoscopy among veterans; however, results about test modality preferences were mixed among all other sub-populations. More focus on directly eliciting preferences for specific test attributes may help to clarify our understanding of which modality or screening program design would be ideal for specific sub-populations. Studies that investigated test attributes tended to find that accuracy, sensitivity, costs, frequency of test, convenience, and comfort were important. Accuracy and sensitivity were often associated with colonoscopy, while convenience was often associated with fecal testing. Regardless of the preferred modality, accuracy was the single most common attribute identified across sub-populations. In systematic reviews that focused on the general population, accuracy was also identified as an important attribute and no specific modality was dominantly preferred.Citation20–Citation22

The studies that measured preference for decision-making pointed to shared decision-making between patients and providers, highlighting a willingness by vulnerable patients to engage in productive and collaborative efforts to receive screening. This is paramount since consideration of patient preferences in terms of testing attributes can be combined with provider expertise to reach an optimal screening strategy. This review provides support for the use of decision aids among vulnerable sub-populations as a method of educating patients about their options and allowing patients to clarify their preferences regarding test features and screening modalities.Citation43,Citation87–Citation89

This study includes several strengths. This is the first systematic review, to our knowledge, to address CRC screening preferences among vulnerable populations, compiling studies from more than a 20-year timeframe. We also highlighted the relatively large number of studies focused on modality preferences and the limited research available on other important features of the decision-making process.

However, there were also a number of limitations. In order to gauge the scope of articles addressing vulnerable patients’ CRC screening preferences, we included a broad range of study designs, focus populations and outcome measurement, so the studies are not all directly comparable. For example, given that a large proportion of the studies primarily addressing low-income patients were international, cultural contexts may have influenced the results, making it difficult to generalize to US sub-populations. There may also be additional populations that could be considered vulnerable in this context, such as patients who are illiterate or have low educational levels, not included in this review. In addition, the intersectionality of identities among the vulnerable populations made it difficult to elicit a specific preference for a singular categorization. As a result, we caution against making sweeping generalizations about the preferences of these sub-groups, due to the variety of factors that influence preferences for CRC screening in specific sub-populations. Instead, this review elicited trends and themes from the literature and can be used as a guide for planning and implementing CRC screening interventions that are well-aligned with patients’ stated preferences, underlying barriers and facilitators to screening, and realities of local settings and contexts.Citation90

This systematic review highlights several opportunities for future research to ensure CRC screening programs better align with the preferences of vulnerable patients and ultimately to improve their CRC screening rates. First, more standardized methods to capture preferences, such as discrete choice experiments and conjoint analyses, may be needed to clarify tradeoffs, especially since a single modality preference was not found. Although many discrete choice experiments focused on CRC screening were conducted among the general population, few have focused on specific vulnerable sub-groups. Second, since multiple modalities are generally acceptable, it will be important to determine how frequently providers are offering multiple test options. Third, future research should consider the best approach to presenting screening test options to vulnerable patients in order to create a balance between providing patients with options that are consistent with their values and offer them flexibility but not providing an overwhelming number of options and features to consider. This is especially critical given that patients reported interest in a shared decision-making process, but it remains unclear how providers should initiate these discussions. Fourth, preference studies should be conducted among those groups for whom preferences have not yet been assessed, such as disabled individuals and LGBTQ individuals. Finally, assessment activities are needed to inform intervention design and create alignment between testing preferences and screening interventions.

Conclusion

Our systematic review of CRC screening preferences in vulnerable populations revealed substantial heterogeneity in outcomes measured, study design, and populations studied and demonstrated a wide spectrum of CRC screening preferences across different vulnerable populations. This review echoes the results of previous systematic reviews conducted on CRC screening preferences among the general population in that there is no specific test modality that is overwhelmingly supported by vulnerable populations; rather, having a choice between modalities may be preferred, especially in the context of shared decision-making, which vulnerable patients seem to value. All studies measuring patients’ preferences for decision-making included in this review pointed to an engaged and shared decision-making between the patient and provider. In addition, screening test attributes such as accuracy, sensitivity, cost, and convenience are important features to consider. More studies that measure the various aspects of preference beyond test modalities alone are needed in the current literature.

To increase CRC screening overall, special attention must be paid to vulnerable populations that struggle with a lower screening uptake due to differential preferences and other reasons that may diverge from the general population (eg, ability to access and pay for follow-up care). The diverse findings reported in this review point to the increased value of decision aids to elicit individually how vulnerable patients weigh certain attributes against each other when making a screening decision. Improvements in CRC screening rates may be achieved through the alignment of vulnerable sub-populations’ preferences with screening program delivery and provider practices, through decision aids or other approaches that seek to clarify and enhance patients’ screening decisions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported, in part, by Cooperative Agreement Number U48-DP005017 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Prevention Research Centers Program and the National Cancer Institute, as part of the Cancer Prevention and Control Research Network. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the funders.

Disclosure

SBW received unrelated grant funding to her institution from Pfizer. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Cancer Facts & Figures2017 Available from: https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2017.htmlAccessed March 3, 2018

- MariottoABYabroffKRShaoYFeuerEJBrownMLProjections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020J Natl Cancer Inst2011103211712821228314

- WhitlockEPLinJSLilesEBeilTLFuRScreening for colorectal cancer: a targeted, updated systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task ForceAnn Intern Med2008149963865818838718

- MaciosekMVSolbergLICoffieldABEdwardsNMGoodmanMJColorectal cancer screening: health impact and cost effectivenessAm J Prev Med2006311808916777546

- ShidaHBanKMatsumotoMAsymptomatic colorectal cancer detected by screeningDis Colon Rectum19963910113011358831529

- U.S. Preventive Services Task ForceScreening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statementAnn Intern Med2008149962763718838716

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)Vital signs: col-orectal cancer screening test use-United States, 2012MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep2013624488188824196665

- Society ACColorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2017–2019Atlanta, GAAmerican Cancer Society2017

- CancerCancer | Healthy People2020 Available from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/cancer/objectivesAccessed November 1, 2017

- GoelMSWeeCCMccarthyEPDavisRBNgo-MetzgerQPhillipsRSRacial and ethnic disparities in cancer screening: the importance of foreign birth as a barrier to careJ Gen Intern Med200318121028103514687262

- JacksonCSOmanMPatelAMVegaKJHealth disparities in colorectal cancer among racial and ethnic minorities in the United StatesJ Gastrointest Oncol20167Suppl 1S32S4327034811

- JamesTMGreinerKAEllerbeckEFFengCAhluwaliaJSDisparities in colorectal cancer screening: a guideline-based analysis of adherenceEthn Dis200616122823316599375

- DeckerKMSinghHReducing inequities in colorectal cancer screening in North AmericaJ Carcinog2014131225506266

- LissDTBakerDWUnderstanding current racial/ethnic disparities in colorectal cancer screening in the United States: the contribution of socioeconomic status and access to careAm J Prev Med201446322823624512861

- WalshJMPosnerSFPerez-StableEJColon cancer screening in the ambulatory settingPrev Med200235320921812202062

- KiviniemiMTHayJLJamesASDecision making about cancer screening: an assessment of the state of the science and a suggested research agenda from the ASPO Behavioral Oncology and Cancer Communication Special Interest GroupCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev200918113133313719900944

- NguyenTTMcpheeSJPatient-provider communication in cancer screeningJ Gen Intern Med200318540240312795740

- PignoneMBucholtzDHarrisRPatient preferences for colon cancer screeningJ Gen Intern Med199914743243710417601

- GeigerTMRicciardiRScreening options and recommendations for colorectal cancerClin Colon Rectal Surg200922420921721037811

- WortleySWongGKieuAHowardKAssessing stated preferences for colorectal cancer screening: a critical systematic review of discrete choice experimentsPatient20147327128224652475

- GhanouniASmithSGHalliganSPublic preferences for colorectal cancer screening tests: a review of conjoint analysis studiesExpert Rev Med Devices201310448949923895076

- MarshallDMcgregorSECurrieGMeasuring preferences for colorectal cancer screening: what are the implications for moving forward?Patient201032798922273359

- HegartyVBurchettBMGoldDTCohenHJRacial differences in use of cancer prevention services among older AmericansJ Am Geriatr Soc200048773574010894310

- SambamoorthiUMcalpineDDRacialMDDRacial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and access disparities in the use of preventive services among womenPrev Med200337547548414572431

- ElnickiDMMorrisDKShockcorWTPatient-perceived barriers to preventive health care among indigent, rural Appalachian patientsArch Intern Med199515544214247848026

- ShiLLebrunLAZhuJTsaiJCancer screening among racial/ethnic and insurance groups in the United States: a comparison of disparities in 2000 and 2008J Health Care Poor Underserved201122394596121841289

- SolbergLIBrekkeMLKottkeTEAre physicians less likely to recommend preventive services to low-SES patients?Prev Med19972633503579144759

- MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJAltmanDGPRISMA GroupPreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statementPLoS Med200967e100009719621072

- RivaJJMalikKMBurnieSJEndicottARBusseJWWhat is your research question? An introduction to the PICOT format for cliniciansJ Can Chiropr Assoc201256316717122997465

- National Quality ForumA roadmap for promoting health equity and eliminating disparities: the four I’s for health equity Available from: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2017/09/A_Roadmap_for_Promoting_Health_Equity_and_Eliminating_Disparities__The_Four_I_s_for_Health_Equity.aspxAccessed April 5, 2018

- FiscellaKSandersMRRacial and ethnic disparities in the quality of health careAnnu Rev Public Health20163737539426789384

- KohHKOppenheimerSCMassin-ShortSBEmmonsKMGellerACViswanathKTranslating research evidence into practice to reduce health disparities: a social determinants approachAm J Public Health2010100Suppl 1S72S8020147686

- KondoKLowAEversonTHealth disparities in veterans: a map of the evidenceMed Care201755S9S1528806361

- KrahnGLWalkerDKCorrea-de-AraujoRPersons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity populationAm J Public Health2015105Suppl 2S198S20625689212

- Institute of Medicine (IOM)Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st CenturyWashington, DCNational Academies Press2001

- Institute of Medicine (IOM)Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health CareWashington, DCNational Academies Press2003

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)2015National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report and 5th Anniversary Update on the National Quality StrategyRockville, MDAHRQ2016 Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr15/index.htmlAccessed April 5, 2018

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)2016National Healthcare Quality and Disparities ReportRockville, MDAHRQ2017

- HHS, Office of Minority HealthNational Stakeholder Strategy for Achieving Health EquityWashington, DCHHS2016 Available from: http://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/npa/files/Plans/NSS/NSS_05_Section1.pdfAccessed 20 August 2018

- HHSLGBT Health and Well-Being Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/programs/topic-sites/lgbt/reports/health-objectives-2015.html Accessed April 5, 2018

- LevinBBondJHColorectal cancer screening: recommendations of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. American Gastroenterological AssociationGastroenterology19961115138113848898654

- AbolaMVFennimoreTFChenMMStool DNA-based versus colonoscopy-based colorectal cancer screening: patient perceptions and preferencesFam Med Community Health20153328

- BrennerATHoffmanRMcwilliamsAColorectal cancer screening in vulnerable patients: promoting informed and shared decisionsAm J Prev Med201651445446227242081

- CalderwoodAHWasanSKHeerenTCSchroyPCPatient and provider preferences for colorectal cancer screening: how does CT colonography compare to other modalities?Int J Canc Prev20114430733825237287

- ChablaniSVCohenNWhiteDItzkowitzSHDuhamelKJandorfLColorectal cancer screening preferences among Black and Latino primary care patientsJ Immigr Minor Health20171951100110827351895

- DebourcyACLichtenbergerSFeltonSButterfieldKTAhnenDJDenbergTDCommunity-based preferences for stool cards versus colonoscopy in colorectal cancer screeningJ Gen Intern Med200823216917418157581

- EllisonJJandorfLDuhamelKColonoscopy screening information preferences among urban HispanicsJ Immigr Minor Health201113596396620607609

- GreinerKABornWNollenNAhluwaliaJSKnowledge and perceptions of colorectal cancer screening among urban African AmericansJ Gen Intern Med2005201197798316307620

- HardenEMooreAMelvinCExploring perceptions of colorectal cancer and fecal immunochemical testing among African Americans in a North Carolina communityPrev Chronic Dis201186A13422005627

- HawleySTMcqueenABartholomewLKPreferences for colorectal cancer screening tests and screening test use in a large multispecialty primary care practiceCancer2012118102726273421948225

- HawleySTVolkRJKrishnamurthyPJibaja-WeissMVernonSWKneuperSPreferences for colorectal cancer screening among racially/ethnically diverse primary care patientsMed Care2008469 Suppl 1S10S1618725820

- JoAMMaxwellAEWongWKBastaniRColorectal cancer screening among underserved Korean Americans in Los Angeles CountyJ Immigr Minor Health200810211912617574545

- MartensCECrutchfieldTMLapingJLWhy wait until our community gets cancer?: exploring CRC screening barriers and facilitators in the Spanish-speaking community in North CarolinaJ Cancer Educ201631465265926264390

- MessinaCRLaneDSGrimsonRColorectal cancer screening attitudes and practices preferences for decision makingAm J Prev Med200528543944615894147

- MolokwuJCPenarandaEShokarNDecision-making preferences among older Hispanics participating in a colorectal cancer (CRC) screening programJ Community Health20174251027103428421426

- MyersREHyslopTSifriRTailored navigation in colorectal cancer screeningMed Care2008469 Suppl 1S123S13118725824

- PalmerRCMidgetteLAMullanIDColorectal cancer screening preferences among African Americans: which screening test is preferred?J Cancer Educ201025457758120229075

- RuffinMTCreswellJWJimboMFettersMDFactors influencing choices for colorectal cancer screening among previously unscreened African and Caucasian Americans: findings from a triangulation mixed methods investigationJ Community Health2009342798919082695

- SchroyPCEmmonsKPetersEThe impact of a novel computer-based decision aid on shared decision making for colorectal cancer screening: a randomized trialMed Decis Making20113119310720484090

- SchroyPCHeerenTCPatient perceptions of stool-based DNA testing for colorectal cancer screeningAm J Prev Med200528220821415710277

- SchroyPCLalSGlickJTRobinsonPAZamorPHeerenTCPatient preferences for colorectal cancer screening: how does stool DNA testing fare?Am J Manag Care200713739340017620034

- SheikhRAKapreSCalofOMWardCRainaAScreening preferences for colorectal cancer: a patient demographic studySouth Med J200497322423015043327

- ShokarNKCarlsonCAWellerSCInformed decision making changes test preferences for colorectal cancer screening in a diverse populationAnn Fam Med20108214115020212301

- ShokarNKVernonSWWellerSCCancer and colorectal cancer: knowledge, beliefs, and screening preferences of a diverse patient populationFam Med200537534134715883900

- TaberJMAspinwallLGHeichmanKAKinneyAYPreferences for blood-based colon cancer screening differ by race/ethnicityAm J Health Behav201438335136124636031

- WolfRLBaschCEBrouseCHShmuklerCSheaSPatient preferences and adherence to colorectal cancer screening in an urban populationAm J Public Health200696580981116571715

- WolfRLBaschCEZybertPPatient test preference for colorectal cancer screening and screening uptake in an insured urban minority populationJ Community Health201641350250826585609

- ZapatierJAKumarARPerezAGuevaraRSchneiderAPreferences for ethnicity and sex of endoscopists in a Hispanic population in the United StatesGastrointest Endosc2011731899721184874

- ChoYHKimDHChaJMPatients’ preferences for primary colorectal cancer screening: a survey of the national colorectal cancer screening program in KoreaGut Liver201711682182728750489

- FrewEWolstenholmeJLWhynesDKWillingness-to-pay for colorectal cancer screeningEur J Cancer200137141746175111549427

- QuickBWHesterCMYoungKLGreinerKASelf-reported barriers to colorectal cancer screening in a racially diverse, low-income study populationJ Community Health201338228529222976770

- SaengowUChongsuwiwatvongVGeaterABirchSPreferences and acceptance of colorectal cancer screening in ThailandAsian Pac J Cancer Prev20151662269227625824749

- WallerJMacedoAvon WagnerCCommunication about colorectal cancer screening in Britain: public preferences for an expert recommendationBr J Cancer2012107121938194323175148

- WongMCTsoiKKNgSSA comparison of the acceptance of immunochemical faecal occult blood test and colonoscopy in colorectal cancer screening: a prospective study among ChineseAliment Pharmacol Ther2010321748220345501

- WongMCJohnGKHiraiHWChanges in the choice of colorectal cancer screening tests in primary care settings from 7,845 prospectively collected surveysCancer Causes Control20122391541154822836914

- XuYLevyBTDalyJMBergusGRDunkelbergJCComparison of patient preferences for fecal immunochemical test or colonoscopy using the analytic hierarchy processBMC Health Serv Res20151517525902770

- AkerkarGAYeeJHungRMcquaidKPatient experience and preferences toward colon cancer screening: a comparison of virtual colonoscopy and conventional colonoscopyGastrointest Endosc200154331031511522970

- Friedemann-SánchezGGriffinJMPartinMRGender differences in colorectal cancer screening barriers and information needsHealth Expect200710214816017524008

- ImaedaABenderDFraenkelLWhat is most important to patients when deciding about colorectal screening?J Gen Intern Med201025768869320309740

- MoawadFJMaydonovitchCLCullenPABarlowDSJensonDWCashBDCT colonography may improve colorectal cancer screening complianceAJR201019551118112320966316

- PowellAABurgessDJVernonSWColorectal cancer screening mode preferences among US veteransPrev Med200949544244819747502

- RajapaksaRCMacariMBiniEJRacial/ethnic differences in patient experiences with and preferences for computed tomography colonography and optical colonoscopyClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20075111306131217689294

- PhamRCrossSFernandezB“Finding the right FIT”: rural patient preferences for fecal immunochemical test (FIT) characteristicsJ Am Board Fam Med201730563264428923816

- PignoneMPCrutchfieldTMBrownPMUsing a discrete choice experiment to inform the design of programs to promote colon cancer screening for vulnerable populations in North CarolinaBMC Health Serv Res20141461125433801

- PhillipsCDMcleroyKRHealth in rural America: remembering the importance of placeAm J Public Health200494101661166315451725

- LópezGBialikKKey findings about US immigrantsPew Research Center Available from: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/05/03/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/Accessed April 1, 2018

- HoffmanASLowensteinLMKamathGRAn entertainment-education colorectal cancer screening decision aid for African American patients: a randomized controlled trialCancer201712381401140828001305

- ReulandDSBrennerATHoffmanREffect of combined patient decision aid and patient navigation vs usual care for colorectal cancer screening in a vulnerable patient population: a randomized clinical trialJAMA Intern Med2017177796797428505217

- VolkRJLinderSKLopez-OlivoMAPatient decision aids for colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review and meta-analysisAm J Prev Med201651577979127593418

- WheelerSBDavisMM“Taking the bull by the horns”: four principles to align public health, primary care, and community efforts to improve rural cancer controlJ Rural Health201733434534928905432