Abstract

Background

Medication nonadherence is a global problem that requires urgent attention. Primary nonadherence occurs when a patient consults with a medical doctor, receives a referral for medical therapy but never fills the first dispensation for the prescription medication. Nonadherence to chronic disease medications costs the USA ~$290 billion (USD) every year in avoidable health care costs. In Canada, it is estimated that 5.4% of all hospitalizations are due to medication nonadherence.

Objectives

The objective of this study was to quantify the extent of primary nonadherence for four of the most common chronic disease medications. The second objective was to identify factors associated with primary nonadherence to chronic disease medications.

Materials and methods

We conducted an extensive systematic literature review of eight databases with a wide range of keywords. We identified relevant articles for primary nonadherence to antihypertensives, lipid-lowering agents, hypoglycemics, and antidepressants. After further screening and assessment of methodologic quality, relevant data were extracted and analyzed using a random-effects model.

Results

Twenty-four articles were included for our meta-analysis after full review and assessment for risk of bias. The pooled primary nonadherence rate for the four chronic disease medications was 14.6% (95% CI: 13.1%–16.2%). Primary medication nonadherence was higher for lipid-lowering medications among the four chronic disease medications assessed (20.8%; 95% CI: 16.0%–25.6%). The rates in North America (17.0%; 95% CI: 14.4%–19.5%) were twice those from Europe (8.5%; 95% CI: 7.1%–9.9%). The absence of social support (20%; 95% CI: 14.4%–26.6%) was the most common sociodemographic variable associated with chronic disease medication primary nonadherence.

Conclusion

Evidence suggests that a considerable percentage of patients do not initially fill their medications for treatable chronic diseases or conditions. This represents a major health care problem that can be successfully addressed. Efforts should be directed toward proper medication counseling, patient social support, and clinical follow-up, especially when the indications for the prescribed medication aim to provide primary prevention.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) reviewed the literature on secondary nonadherence to chronic disease prescription medications and concluded the following: 1) medications do not work if patients do not take them, 2) medication nonadherence is a worldwide problem that crosses all jurisdictions, 3) the prevalence of medication nonadherence is of striking magnitude, and 4) this complex issue should be an urgent priority for policy makers and health care providers.Citation1 The analysis from the WHO was restricted to secondary nonadherence (patient quits taking medications after starting medical therapy).

Primary nonadherence occurs when a patient consults with a medical doctor, receives a referral for medical therapy, but never fills the first dispensation for the prescription medication.Citation2 There are few articles published in the medical literature on primary nonadherence to prescription medications.Citation1 For example, in the province of Saskatchewan, Canada, the Health Quality Council concluded that only 29% of patients fill prescriptions for statin medications within 90 days of being hospitalized for a heart attack.Citation3

The impact of medication nonadherence is significant. A research article from Canada demonstrated that 5.4% of all hospitalizations were due to medication nonadherence and that the subsequent total annual cost burden is as high as $1.6 billion Canadian dollars.Citation4 Estimates from a study in the USA suggest that nonadherence to chronic disease medications cost the health care system $290 billion American dollars every year.Citation5,Citation6 Besides the cost implications, the impact to human health and quality of life could be enormous. Medication nonadherence is of paramount concern as current evidence suggests that placing an emphasis on efforts to address this important issue could potentially save more lives than discovering new medical innovations to tackle the conditions for which these medications are prescribed.Citation7,Citation8

Global improvements in care and prolonged life expectancy have led not only to an increase in the burden of chronic diseases but also a consequent rise in the number of medication prescriptions and increased budgetary spending on chronic diseases.Citation9 Chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia are among the predominant chronic conditions, and these ailments contribute directly and indirectly to 68% of all deaths worldwide.Citation10 Though not commonly categorized as a chronic condition, depression is the most disabling condition worldwide, contributing significantly to disease and medication prescription burden.Citation11

Clearly, addressing the issues concerning medication nonadherence can have far-reaching implications toward improving the health and well-being of individuals and entire populations. The amount of research work published on primary medication nonadherence (PMNA) is varied with wide-ranging estimates of the effect size.Citation3,Citation12–Citation17 As such, this study seeks to obtain a pooled estimate of the impact of primary nonadherence to chronic disease medications and identify factors that might be contributing to this important issue.

Materials and methods

Data sources and study selection

This study sought to determine the PMNA rate to four common chronic disease medications. The four medication categories considered were antihypertensives, lipid-lowering agents, hypoglycemics, and antidepressants.

PMNA was determined in one of two ways: 1) the proportion of participants who failed to pick up a medication prescribed by their health professional (patient level of measurement) or 2) the proportion of all prescriptions that were not picked up within a specified time (prescription level of measurement).Citation18 Measurements made at the patient level can over- or underestimate the true PMNA, which is typically much closer to measurements made at the prescription level.Citation19

We conducted an extensive systematic search of the following electronic databases: Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane central, Embase, MEDLINE, ProQuest, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Scopus. Our search was conducted using a combination of several keywords outlined in the search strategy for each database searched (Supplementary materials).

In determining the articles to be included in this study, the authors first eliminated duplicates using the EndNote reference management software. The remaining articles were then screened by their titles and abstracts for relevance. Afterward, two of the authors (CN and ML) reviewed the full-text articles independently for relevance and agreement with the predetermined inclusion criteria (Supplementary materials) to obtain the final articles to be included for the analysis. Methodologic quality and the risk of bias were also independently assessed by two reviewers (CN and ML) by using an adaptation of the Cochrane risk-of-bias toolCitation20 and a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale.Citation21 Any disagreements between the reviewing authors (CN and ML) were further discussed and deliberated upon for a possible resolution, and when an agreement was still not possible, a tie-breaking vote was cast by the final author (JM).

Data extraction

PMNA rates alongside the total number of participants (n) in each study were extracted from each of the included studies. Other relevant information extracted from each study included the type of medication prescribed, the duration of follow-up or observation, the study design, whether the data were from large administrative databases or smaller hospital databases, the average age of study participants, the study location, and the presence or absence of social support (which was defined as some form of routine contact between the health care professional and the participants either through regular follow-ups, text messages, or calls; with the principal aim of improving medication adherence).

Data analysis

The 95% CI of the included studies was determined using the extracted proportions and the sample size (n). The pooled estimate was obtained using a random-effects model to account for clinical heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was statistically assessed using Higgins I-squaredCitation22 and further explored with the aid of a subgroup analysis based on categorizations determined a priori. An influence analysis using Tobias’ methodCitation23 was carried out to ascertain the robustness and effect each individual study had on the overall pooled estimate. This involved re-estimating the pooled effect with each study omitted in turn and then assessing whether the overall estimate was skewed significantly. Publication bias was assessed statistically using Begg’s test.Citation24 All analyses used the “metaprop_one” command and were performed with STATA version 13.1.

Results

Study selection

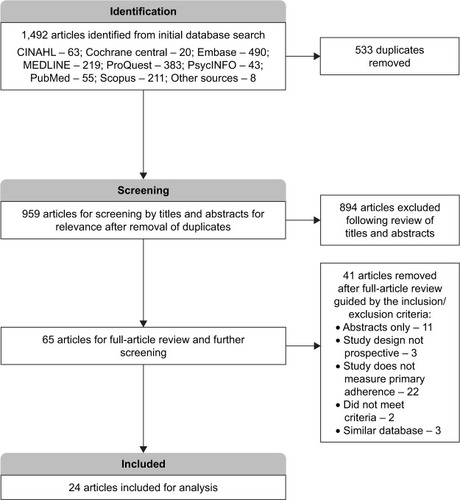

A total of 1,492 articles were obtained from the initial search and this was narrowed to 959 articles after deduplication by use of the reference management software. Of the remaining studies, 894 were found to be unrelated to our study and, therefore, removed after careful screening by their titles and abstracts. Guided by the inclusion and exclusion criteria determined a priori, complete copies of the 65 remaining articles were obtained and further screened for relevance. After reviewing the full articles, 24 studiesCitation3,Citation12,Citation14–Citation16,Citation19,Citation25–Citation42 were deemed appropriate for inclusion and underwent risk-of-bias assessment and further analysis (). A detailed description of the studies included is provided in .

Table 1 Description of included studies

Risk-of-bias assessment

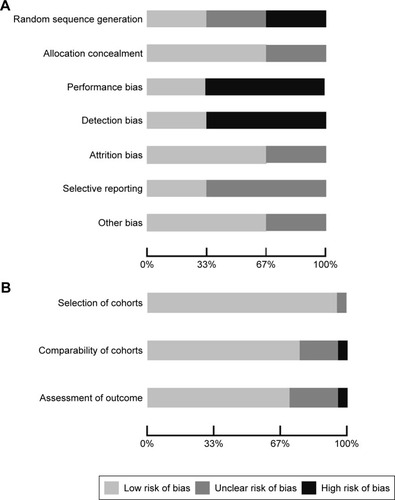

Of the selected final 24 articles, 13 were determined to have a low risk of bias, eight were unclear, and three had a high risk of bias. The main methodology concerns among the included experimental studies were centered on performance bias (besides the intervention of interest, researchers acted or treated participants in control or treatment group differently) and detection bias (systematic differences in the measurement of the outcome across both groups). The strengths among the experimental studies included adequate outcome data at follow-up and proper concealment of participant allocation. For the observational studies included for analysis, selection of the cohort of interest was adequate and there was minimal bias noted with the comparability of the cohorts and assessment of the outcome ().

Characteristics of the pool

A total of 550,485 prescriptions were pooled from the 24 included studies, with 64,892 of those prescriptions not being redeemed within the defined period (). Seventeen of the included studies assessed PMNA by following up 467,483 prescriptions for a 3-month duration or less,Citation15,Citation16,Citation19,Citation25,Citation26,Citation28,Citation29,Citation31–Citation39,Citation41 while seven studies assessed PMNA among 83,002 prescriptions over an extended time-frame (ie, >3 months).Citation3,Citation12,Citation14,Citation27,Citation30,Citation40,Citation42 Eight studies determined PMNA at the level of the prescription.Citation12,Citation14,Citation16,Citation19,Citation26,Citation34,Citation40,Citation42 The highest number of chronic disease medication prescriptions identified in this study were for antihypertensives (190,658), followed closely by antidepressants (164,542), lipid-lowering medications (149,714), and hypoglycemics (45,571). A majority (16) of the studies were retrospective cohort studies,Citation3,Citation12,Citation14–Citation16,Citation19,Citation25,Citation26,Citation28,Citation32–Citation35,Citation38,Citation39,Citation41,Citation42 while seven studies were either prospective cohorts or clinical trials.Citation27,Citation29–Citation31,Citation36,Citation37,Citation40 Six of the included studies were conducted in Europe,Citation14,Citation19,Citation26,Citation30,Citation32,Citation33 while the rest were in either the United States or Canada.Citation3,Citation12,Citation15,Citation16,Citation25,Citation27–Citation29,Citation31,Citation34–Citation36,Citation37–Citation42 All but seven of the studies utilized data from large administrative databasesCitation9,Citation14–Citation16,Citation19,Citation25,Citation26,Citation28,Citation29,Citation32,Citation34,Citation35,Citation37–Citation39,Citation41,Citation42 ().

Table 2 Pooled estimates

Table 3 Subgroup analysis

Pooled analyses

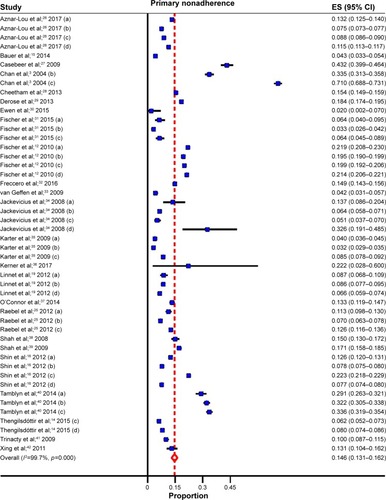

Overall, the pooled estimates showed that the incidence of PMNA for the four most common chronic diseases was 14.6% (95% CI: 13.1%–16.2%) (; ). These estimates were unlikely to be influenced by bias, as PMNA did not differ significantly in the studies with a low risk of bias when compared to those with an unclear or high risk of bias (). Variation between the studies was addressed using a random-effects model and a subgroup analysis was carried out to further explore the potential reasons for between-study variations.

Figure 3 Forest plot for primary medication nonadherence.

Abbreviation: ES, effect size.

The following findings were of interest. The only sociodemographic variable with a consistent association with PMNA was lack of social support. Those without social support had higher rates of PMNA (20%; 95% CI: 14.4%–26.6%) than those with social support (13.1%; 95% CI: 11.4%–14.8%). Other variables, like age, demonstrated inconsistent associations. PMNA for lipid-lowering medications like statins (20.8%; 95% CI: 16.0%–25.6%) was higher than the PMNA rates for antihypertensives (12.4%; 95% CI: 9.5%–15.3%), hypoglycemics (13.2%; 95% CI: 9.6%–16.8%), and antidepressants (10.8%; 95% CI: 8.2%–13.4%). The extent of PMNA for North America (17.0%; 95% CI: 14.4%–19.5%) was twice the rate estimated for Europe (8.5%; 95% CI: 7.1%–9.9%). Another significant finding was that studies with prescription follow-up lasting >3 months (25.3%; 95% CI: 19.7%–30.9%) had more than twice the PMNA, compared to those where the studies follow patients for 3 months or less (10.0%; 95% CI: 8.7%–11.4%). Where prospective cohort study designs or clinical trials were used, PMNA was higher, but not significant, compared to retrospective cohort studies. Similarly, PMNA was higher for studies obtained from hospital databases compared to those from large administrative databases but the association was not significant ().

Influential analyses carried out following Tobias’ method showed that the pooled estimates did not vary significantly with the exclusion of any one study. This suggests that none of the studies had a significant influential effect on the overall estimates (Supplementary materials). Publication bias was assessed statistically using Begg’s test. The test was not statistically significant (adjusted Kendall’s score=208, P=0.066), suggesting that publication bias was unlikely.

Discussion

The WHO has identified the issue of medication nonadherence as a global concern and one that requires urgent intervention.Citation1 In our meta-analysis, we found that on average 15 of every 100 medications prescribed for chronic diseases or conditions are not initially filled by patients. Cost barriers play a key role in promoting medication non-adherence.Citation43

For secondary nonadherence to chronic disease medications, two meta-analyses reviewed nonadherence to statins (49.0%; 95% CI: 48.9%–49.2%) and antihypertensive medications (48.5%; 95% CI: 47.7%–49.2%) in real-world settings.Citation2,Citation44 If we put together the findings from these two meta-analyses on secondary nonadherence, along with the findings from our meta-analysis that showed primary nonadherence of 14.6%, we can extrapolate that ~41.8% of patients are adherent to chronic disease or chronic condition medications (49% of 85.4% equals 41.8%). Placing these figures alongside the cost estimates from the New England Health Institute, one can preliminarily ascertain that if steps were taken to reduce the PMNA rate for chronic disease medications by even 1% (on an absolute level – not relative) it can potentially save the US health care system ~$2.9 billion (USD) annually.Citation6

Our subgroup analysis showed that lipid-lowering medications like statins had the highest rate of PMNA for the chronic disease medications (20.8%). A plausible explanation for the observed high PMNA rate is that these medications are often used for primary prevention and, therefore, patients may feel that there is no immediate threat to their health.Citation2,Citation45 This was not the case with hypoglycemic or antidepressant medications, where the common indications for use have clear morbidity and mortality implications that can be easily recognized by patients.

Additionally, we found a difference between the PMNA rates for chronic disease medications when we stratified by the location of the study. Prescriptions for medications based out of Europe had a PMNA rate of 8.5%, while those from North America had PMNA rates of 17.0%. These differences may be related to the variations in the delivery of care and the cost of health care in these regions. In most cases, European nations have stronger social programs that include universal health care coverage with a greater percentage of public funding.Citation46,Citation47 On the other hand, the North American studies were predominantly from the USA, where universal coverage is limited and there is greater dependence on private insurance systems.Citation47

Our subgroup analysis by the duration of follow-up showed that PMNA rates for studies with a longer period of follow-up (3 months or more) were more than double the rates for those with shorter follow-up (3 months or less). This is expected, as the longer the study duration, the more likely nonadherence will be detected.Citation27 For example, in one study, it took patients an average of ~2 years to fill their first prescription for statin medications.Citation2

The absence of social support was also noted to play a key role in negatively impacting the PMNA rates. These findings are not surprising, as studies in the past have shown a clear relationship between the absence of social support and patient nonadherence.Citation15,Citation27,Citation29,Citation36,Citation37,Citation48,Citation49 Given that social support from clinicians, family members, and friends is a modifiable factor, this variable represents an area of interest and further research.

The Cochrane Collaboration reviewed the literature on the impact of social support on medication nonadherence and concluded that more frequent interaction between doctors and patients was the most effective intervention.Citation50 A second meta-analysis from the Cochrane Collaboration reviewed interventions to specifically improve adherence to lipid-lowering medications. Overall, only one of four patients continued to take medications in the long term. In this review, patient reinforcement and regular reminders were the most promising interventions. The authors concluded that a combination of strategies including reminders, reinforcement, and emphasis on appreciating the patient’s perspective might lead to the most effective strategy.Citation51 Similarly, the National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care performed a systematic review of the literature and advocated that health care professionals 1) adapt their consultation style to the needs of individual patients, 2) make information more accessible and easy to understand for their patients, 3) increase patient involvement in decision making, 4) be aware that patients may have concerns about their prescribed medicines, and 5) recognize that nonadherence is quite common and that they should routinely assess for it in a nonjudgmental way.Citation52

In summary, our meta-analysis helps to provide a more clear and accurate picture of the burden of PMNA, while identifying a number of associated factors. Health care professionals and policy makers should place more emphasis on proper medication counseling, patient social support, and clinical follow-up to help reduce PMNA, especially where the indications for the prescribed medication aim to provide primary prevention.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. There is a high level of congruence between our findings and those reported in the existing literature. However, our study provides a more clear and accurate picture of the PMNA impact because its reported effect estimates are not influenced by any single study. Additionally, the increased sample size obtained from pooling the effects of the included studies provides statistical strength.

Despite its strengths, our study has a few limitations. Given the nature of our study and its reliance on secondary data, we experienced some challenges in handling the residual (unmeasured) confounding effects that may be present within each study (eg, some of the included studies had identified their inability to assess the attitudes and beliefs of patients toward the prescribed medication, when these factors could clearly affect PMNA). Also, some of the values from the included studies might be either under- or overestimated because there is no way to independently verify whether patients either filled or did not fill their prescriptions from other sources or locations (ie, filled in different pharmacies or different states or provinces). Finally, some of the included studies were carried out with populations that could not be entirely generalizable and, therefore, should be interpreted with some level of caution.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SabateéEAdherence to Long Term Therapies: Evidence for ActionWorld Health Organization2003 Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42682/1/9241545992.pdfAccessed November 13, 2017

- LemstraMBlackburnDCrawleyAFungRProportion and risk indicators of nonadherence to statin therapy: a meta-analysisCan J Cardiol201228557458022884278

- ChanBBrossartBHudemaNImproving the Quality of Heart Attack Care in Saskatchewan: Outcomes and Secondary PreventionSaskatoonHealth Quality Council2004

- IskedjianMAddisAEinarsonTEstimating the economic burden of hospitalization due to patient nonadherence in CanadaValue Health20025470471

- Chisholm-BurnsMSpiveyCThe “cost” of medication nonadherence: consequences we cannot afford to acceptJ Am Pharm Assoc2012526823826

- New England Healthcare InstituteThinking Outside the Pillbox: A System-wide Approach to Improving Patient Medication Adherence for Chronic Disease2009 Available from: https://www.nehi.net/writable/publication_files/file/pa_issue_brief_final.pdfAccessed November 13, 2017

- MayCMontoriVMairFWe need minimally disruptive medicineBMJ20093392b280319671932

- TingHShojaniaKMontoriVBradleyEQuality improvement: science and actionCirculation2009119141962197419364989

- ZweifelPFelderSMeiersMAgeing of population and health care expenditure: a red herring?Health Economics19998648549610544314

- World Health OrganizationGlobal Status Report on Noncommunicable DiseasesGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2014 Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/148114/1/9789241564854_eng.pdf?ua=1Accessed November 13, 2017

- World Health OrganizationDepressionWorld Health Organization2017 Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/

- FischerMStedmanMLiiJPrimary medication non-adherence: analysis of 195,930 electronic prescriptionsJ Gen Intern Med201025428429020131023

- PottegårdAChristensenRHoujiAPrimary non-adherence in general practice: a Danish register studyEur J Clin Pharmacol201470675776324756147

- ThengilsdóttirGPottegårdALinnetKHalldórssonMAlmarsdóttirAGardarsdóttirHDo patients initiate therapy? Primary non-adherence to statins and antidepressants in IcelandInt J Clin Pract201569559760325648769

- BauerAParkerMSchillingerDAssociations between antidepressant adherence and shared decision-making, patient-provider trust, and communication among adults with diabetes: diabetes study of Northern California (DISTANCE)J Gen Intern Med2014291139114724706097

- ShinJMcCombsJSanchezRUdallMDeminskiMCheethamCPrimary nonadherence to medications in an integrated healthcare settingAm J Manag Care201218842643422928758

- FischerMChoudhryNBrillGTrouble getting started: predictors of primary medication nonadherenceAm J Med20111241081.e9e22

- LamWFrescoPMedication adherence measures: an overviewBiomed Res Int201521704726539470

- LinnetKHalldorssonMThengilsdottirGEinarssonOJonssonKAlmarsdottirAPrimary non-adherence to prescribed medication in general practice: lack of influence of moderate increases in patient copaymentFam Pract2012301697522964077

- HigginsJGreenSCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]The Cochrane Collaboration2011 Available from: http://www.handbook.cochrane.orgAccessed November 13, 2017

- WellsGSheaBO’ConnellJThe Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-analysis2011 Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.aspAccessed November 13, 2017

- HigginsJThompsonSQuantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysisStat Med200221111539155812111919

- TobiasAAssessing the influences of a single study in meta-analysisStata Tech Bull1999471517

- BeggCMazumdarMOperating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication biasBiometrics199450410887786990

- RaebelMEllisJCarrollNCharacteristics of patients with primary non-adherence to medications for hypertension, diabetes, and lipid disordersJ Gen Intern Med201227576421879374

- Aznar-LouIFernándezAGil-GirbauMInitial medication non-adherence: prevalence and predictive factors in a cohort of 1.6 million primary care patientsBr J Clin Pharmacol20178361328134028229476

- CasebeerLHuberCBennettNImproving the physician-patient cardiovascular risk dialogue to improve statin adherenceBMC Fam Pract2009104819566950

- CheethamTNiuFGreenKPrimary nonadherence to statin medications in a managed care organizationJ Manag Care Pharm201319536737323697474

- DeroseSGreenKMarrettEAutomated outreach to increase primary adherence to cholesterol-lowering medicationsJAMA Internal Medicine201317313823403978

- EwenSMeyerMCremersBBlood pressure reductions following catheter-based renal denervation are not related to improvements in adherence to antihypertensive drugs measured by urine/plasma toxicological analysisClin Res Cardiol2015104121097110526306594

- FischerMJonesJWrightEA randomized telephone intervention trial to reduce primary medication nonadherenceJ Manag Care Spec Pharm201521212413125615001

- FrecceroCSundquistKSundquistJJiJPrimary adherence to antidepressant prescriptions in primary health care: a population-based study in SwedenScand J Prim Health Care2016341838826828942

- van GeffenEGardarsdottirHvan HultenRvan DijkLEgbertsAHeerdinkEInitiation of antidepressant therapy: do patients follow the GP’s prescription?Br J Gen Pract200959559818719192372

- JackeviciusCLiPTuJPrevalence, predictors, and outcomes of primary nonadherence after acute myocardial infarctionCirculation200811781028103618299512

- KarterAParkerMMoffetHAhmedASchmittdielJSelbyJNew prescription medication gaps: a comprehensive measure of adherence to new prescriptionsHealth Serv Res2009445 pt 11640166119500161

- KernerDKnezevichEUse of communication tool within electronic medical record to improve primary nonadherenceJ Am Pharm Assoc2017573S270.e2S273.e2

- O’ConnorPSchmittdielJPathakRHarrisRNewtonKOhnsorgKRandomized trial of telephone outreach to improve medication adherence and metabolic control in adults with diabetesDiabetes Care2014373317332425315207

- ShahNHirschAZackerCTaylorSWoodGStewartWFactors associated with first-fill adherence rates for diabetic medications: a cohort studyJ Gen Intern Med200824223323719093157

- ShahNHirschAZackerCPredictors of first-fill adherence for patients with hypertensionAm J Hypertens200922439239619180061

- TamblynREgualeTHuangAWinsladeNDoranPThe incidence and determinants of primary nonadherence with prescribed medication in primary careAnn Intern Med2014160744124687067

- TrinactyCAdamsASoumeraiSRacial differences in long-term adherence to oral antidiabetic drug therapy: a longitudinal cohort studyBMC Health Serv Res200992419200387

- XingSDiPaulaBLeeHCookeCFailure to fill electronically prescribed antidepressant medicationsPrim Care Companion CNS Disord2011115

- GadkariAMcHorneyCMedication nonfulfillment rates and reasons: narrative systematic reviewCurr Med Res Opin201026368370520078320

- LemstraMAlsabbaghMProportion and risk indicators of non-adherence to antihypertensive therapy: a meta-analysisPatient Prefer Adherence2014821121824611002

- ColhounHBetteridgeDDurringtonPCARDS investigatorsPrimary prevention of cardiovascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS): multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trialLancet2004364943568569615325833

- KringosDBoermaWVan Der ZeeJGroenewegenPEurope’s strong primary care systems are linked to better population health but also to higher health spendingHealth Aff (Millwood)201332468669423569048

- RidicGGleasonSRidicOComparisons of health care systems in the United States, Germany and CanadaMater Sociomed201224211212023678317

- LemstraMBirdYNwankwoCRogersMMorarosJWeight loss intervention adherence and factors promoting adherence: a meta-analysisPatient Prefer Adherence2016101547155927574404

- DiMatteoMSocial support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysisHealth Psychol200423220721815008666

- HaynesRBYaoXDeganiAKripalaniSGargAMcDonaldHPInterventions for enhancing medication adherenceCochrane Database Syst Rev20054CD00001116235271

- SchedlbauerADaviesPFayeyTInterventions to improve adherence to lipid lowering medicationCochrane Database Syst Rev20103CD00437120238331

- NunesVNeilsonJO’flynnNClinical guidelines and evidence review for medicines adherence: involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherenceLondonNational Collaborating Centre for Primary Care and Royal College of General Practitioners2009 Available from: http://www.sefap.it/servizi_lineeguida_200902/CG76FullGuidelineApp.pdfAccessed November 13, 2017