Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate and compare medication adherence to chronic therapies in older populations across different regions in Europe.

Methods

This explorative study applied a harmonized method of data extraction and analysis from pharmacy claims databases of three European countries to compare medication adherence at a cross-country level. Data were obtained for the period between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2011. Patients (aged ≥65 years) who newly initiated to oral antidiabetics, antihyperlipidemics, or antiosteoporotics were identified and followed for over a 12-month period. Main outcome measures were medication adherence (medication possession ratio, [MPR]; implementation) and persistence on index treatment. All country-specific data sets were prepared by employing a common data input model. Outcome measures were calculated for each country and pooled using random effect models.

Results

In total, 39,186 new users were analyzed. In pooled data from the three countries, suboptimal implementation (MPR <80%) was 52.45% (95% CI: 33.43–70.79) for antihy-perlipidemics, 61.35% (95% CI: 52.83–69.22) for antiosteoporotics, and 30.33% (95% CI: 25.53–35.60) for oral antidiabetics. Similarly, rates of non-persistence (discontinuation) were 55.63% (95% CI: 35.24–74.29) for antihyperlipidemics, 60.24% (95% CI: 45.35–73.46) for antiosteoporotics, and 46.80% (95% CI: 36.40–57.4) for oral antidiabetics.

Conclusion

Medication adherence was suboptimal with >50% of older people non-adherent to antihyperlipidemics and antiosteoporotics in the three European cohorts. However, the degree of variability in adherence rates among the three countries was high. A harmonized method of data extraction and analysis across health-related database in Europe is useful to compare medication-taking behavior at a cross-country level.

Introduction

The treatment of chronic illnesses often includes the long-term use of pharmacotherapy, but although these medications are effective in treating chronic diseases, their full benefits are often not realized because ~50% of patients do not take their medications as prescribed.Citation1 Recently, a European-funded consortium Ascertaining Barriers to Compliance (ABC) project developed a Taxonomy of Adherence in an effort to standardize the medication-taking behavior terminology and measurement for clinical and research use. The taxonomy defines medication adherence “as the process by which patients take their medication as prescribed” and subdivides adherence into three essential elements, namely initiation, implementation, and discontinuation.Citation2 Nonadherence to medications can thus occur in the following situations or combinations thereof: late or noninitiation of the prescribed treatment, suboptimal implementation of the dosing regimen, or early discontinuation of the treatment (nonpersistence).

It is now well established that medication adherence is often poor, and this is perceived as a major public health problem in Western countries because it decreases the efficacy of pharmacological therapies, while at the same time increases direct and indirect related costs.Citation3 For several reasons, poor adherence is more prevalent in specific groups of patients than in others. Older people experience greater morbidity with a corresponding increase in medication utilization and are at an increased risk of nonadherence.Citation4 Medication adherence rates of 38%–57% have been reported in older populations with an average rate of <45%.Citation4 The European Community acknowledges the relevance of optimizing the prescribing processes as a mandatory element for community health care systems to improve medication adherence in older adults.Citation5 More specifically, this is the main aim of the action Group on Prescription and adherence to Medical Plans of the European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Aging (EIP-AHA).Citation6,Citation7 Under the pillar of “prevention, screening, and early diagnosis,” the EIP on AHA identified “adherence to medication and medical plans” as a priority area in order to deliver tangible adherence approaches for patients in various disease areas, at the regional level and in different member states. As part of the collaborative work conducted in the group, partners identified the use of observational and large-population databases as a tool to investigate evidence on medication adherence in older populations and to facilitate data sharing.Citation4,Citation8

Pharmacy refill data provide an important, valid, and relatively efficient method of assessing retrospective medication adherence in large population-based research.Citation4 However, few studies have undertaken cross-country comparisons of adherence. In general, drug-utilization studies have applied different methods of measurement of adherence across a range of different data sources and populations, making comparisons of the results of these studies difficult. On the other hand, using multiple data sources is not an easy task, as it implies a set of multiple actions to be taken, such as data and meta-data analysis, identification of common data sets, solving privacy and data property issues, and data integration.

The aims of this study were to 1) assess the feasibility of performing a collaborative cross-country comparison of medication adherence based on pooled outpatient dispensing data and 2) to compare medication adherence rates to three highly prevalent drug classes in older populations across three different European cohorts.

Methods

Setting

This was an explorative study that applied a harmonized method of data extraction and analysis across health-related databases in Europe in order to compare medication adherence at a cross-country level. The study was carried out on three health-related databases from three European countries (Republic of Ireland, Italy [Campania Region], and Spain [Aragon Region]).Citation8

Access to health care is public in Italy and Spain, and drug policies are influenced by the central government. In Italy, drugs for the treatment of chronic conditions are fully covered by National Health Services with different levels of fixed or variable co-payment, depending on the drug category, patients’ income, chronic condition, and so on. In Spain, different levels of co-payment have been applied since 2012 depending on patients’ income. The health care system in Ireland, which is predominantly tax-funded, operates as a two-tiered public and private system, with ~40% of the population in receipt of public health insurance (General Medical Services [GMS] patients). The GMS scheme is mean-tested, with a higher income threshold for those aged ≥70 years, and provides individuals with free or substantially subsidized health care and prescription medications. It is estimated that over 75% of adults aged ≥65 years and ~92% of adults aged ≥70 years benefit from the scheme nationally and are subject to a flat co-payment for prescription medication ().Citation9

Table 1 Characteristics of the health care systems of the three European countries

Data sources

The three European electronic health care databases: the EpiChron Cohort in Aragon, Spain; the Health Services Executive Primary Care Reimbursement Services (HSE-PCRS), Ireland; and the Caserta Local Health Unit (LHU) from Campania Region, Italy; collect data on all drugs dispensed through the public health care system and have been shown to be valid for pharmacoepidemiological research.Citation10–Citation13 The characteristics of the databases have been described already by the Adherence Action Group partners, within the context of the EIP-AHA, with the aim to improve data sharing at a European level.Citation8 Drugs were classified according to the World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical code/Defined Daily Dose (ATC/DDD), which made between-country comparisons possible.Citation14 As health-related databases rely on patient information records managed by National Health Services, all data stored in these databases can be considered population-based and a record of medications dispensed. In all three databases, data were managed and analyzed using an anonymous patient code. Data were obtained for the period between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2011.

Data extraction

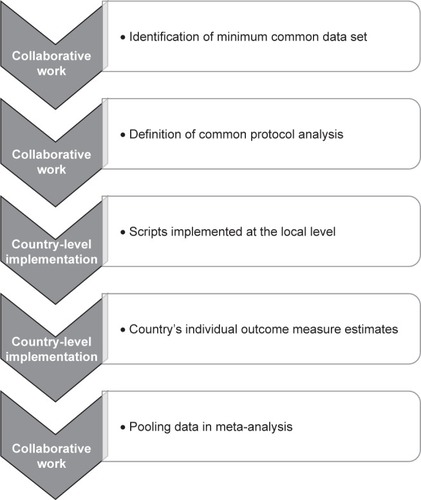

The stepwise process adopted for the definition and harmonization of the queries for data extraction is shown in . In order to facilitate the process of creating a common data structure and to identify a minimum common data set used by all three partners within the network, the investigators designed and completed “Data Definition Form (DDF).” The DDF described the information contained in the data sources used in the project. A common protocol was then developed and shared by partners to standardize definitions and study design, to reduce heterogeneity among individual studies, and to facilitate interpretation of the combined results. Data extraction and analysis scripts were implemented locally using statistical software packages in each database, and only outcome measure estimates were shared; each site wrote their own programs following a standardized protocol. Furthermore, in order to equalize the metrics of adherence evaluation, the researchers designed and filled out a “Metrics Definition Form (MDF)” describing all issues needing consensus among partners.

Study population and study drug categories

The study population in each country consisted of all people aged ≥65 years who had registered within the databases during the study period and who had at least 1 year of valid data (eligibility criterion).

The drug classes investigated in the study were antihyperlipidemics (ATC C10A); oral antidiabetics (ATC A10B except A10BD); and antiosteoporotics (ATC M05B except M05BX). The excluded ATC categories refer to combination therapy; only monotherapy was included in the analysis. New users of the drugs in the ATC class of interest were identified between July 1 and December 31, 2010. The first date when the drug was dispensed was defined as the index date for each individual ATC drug class. A new user was defined as a patient not having any drug dispensed, of the same ATC class, over the 6 months period prior to the index date (wash-out period). Data for each patient were collected for a period of 1 year following the index date. Patients were classified into three treatment groups (per drug class). The treatment groups were not mutually exclusive, and patients could be prescribed all three classes of drugs. Patients’ age (in years) was assessed at the index date, and the patients were classified into the following age groups: 65–74 years, 75–84 years, and >85 years.

Patients receiving combination therapy were excluded from the study as were patients who received only one prescription of the drug class of interest (sporadic users) during the study period.

Days of drug supplied

To calculate the number of days of medication supplied for antiosteoporotics, we used the World Health Organization DDD methodology, which assumes one DDD as 1 day of therapy.Citation14 For antihyperlipidemics and oral antidiabetics, we estimated the number of days or quantity of the drugs supplied per the number of pills based on previous research.Citation15–Citation17

Outcome measures

Definition

Medication adherence on the index treatment was evaluated according to the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research definitions and as per the implementation phase and discontinuation (non-persistence) phase of the ABC taxonomy of medication adherence.Citation2,Citation18 The implementation phase is defined as the extent to which a patient’s actual dosing corresponds to the prescribed dosing regimen, from initiation until the last dose taken. Persistence is the length of time between initiation and the last dose, which immediately precedes discontinuation. Non-persistence was measured as the discontinuation phase, which marks the end of therapy where the next dose is omitted and further doses are not required.

Implementation

Implementation was estimated by calculating the medication possession ratio (MPR) for each of the three drug classes in each country. MPR is a standard method of evaluating drug adherence and is defined as the number of prescribed therapy units divided by the number of assumed therapy units.Citation18 It is calculated as the proportion of the number of days supplied over the intended period of treatment.

MPR was calculated by taking patients’ total days supplied for each class of medication for the 365-day period following the index date and dividing by 365 (100×∑ (days supplied)/365). Patients should have filled at least two prescriptions of the drug class of interest in order to measure their MPR. MPR was expressed as a percentage and truncated to 100 when >100%, as per ESPACOMP recommendations.Citation18 It was calculated per user and per therapeutic subgroup. The threshold for adherence was set at 80% based on Haynes’ definition of adherence to antihypertensive medication; patients with MPR ≥80% were classified as adherent to treatment and those <80% as nonadherent to treatment.Citation19

Discontinuation (non-persistence)

Persistence was estimated by measuring the time gap between a dispensation of a drug and the next dispensation during the follow-up period of 1 year from the index date. All prescription fills/refills were for a 30-day supply. Patients were considered non-persistent if the gap between two refills was longer than 60 days (grace period), based on sensitivity analyses. Medication persistence was evaluated at the drug class level. Patients with at least one discontinuation episode were considered non-persistent. Switching products within index medication classes was not considered as an interruption.

Data synthesis

For each drug class, we calculated new users by age and gender in each country to account for differences in distribution among populations. The rates of nonadherence including implementation and discontinuation (non-persistence) were estimated, by age and gender, at the local level in each country. 95% CIs were obtained using the Clopper– Pearson method. Pooled estimates were obtained using a meta-analytical approach treating each country as a different study. The random-effects model of DerSimonian and Laird was a priori selected due to the anticipated heterogeneity in nonadherence rates.Citation20 Meta-analysis results were displayed using forest plots. The effect of gender and age was assessed by computing pooled OR with the relative 95% CI using a random effect model.

Statistical heterogeneity among countries was investigated using the I2 statistics.Citation21 However, due to the small number of studies, no attempt was made to explore the causes of observed heterogeneity.

All analyses were performed with R statistics (version 3.3.1), using the additional packages META e METAFOR. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

For the Campania data, all procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the current national law from Italian Medicines Agency.Citation51 The manuscript does not comprise clinical studies, and all the patients’ data were fully anonymized. For this type of study, formal consent is not required. Permission to use anonymized data for the present study was granted by the responsible authority, Unità del Farmaco, Regione Campania.

For the EpiChron Cohort, the conformation of the EpiChron Cohort and data utilization for this study counts with the approval of the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Aragon (CEICA – PI17/0024; PI16/088). Data contained in the EpiChron Cohort are not freely available. However, requests for collaborative work are welcome. Please contact the Principal Investigator by email ([email protected]) for further information.

For the HSE-PCRS data, patient consent is not required. Permission to use anonymized data for the present study was granted by Health Services Executive Primary Care Reimbursement Services (HSE-PCRS).Citation52

Results

Study population

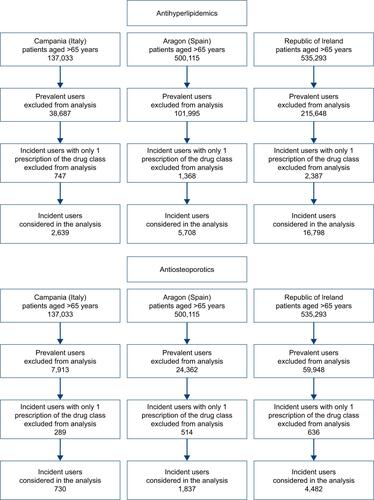

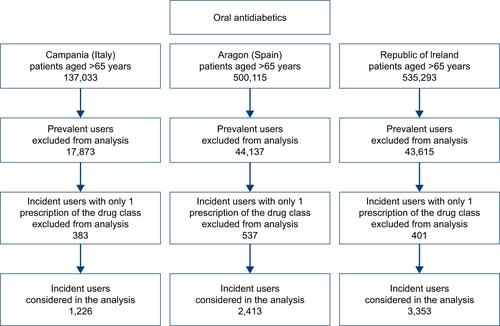

The total population included 1,172,441 patients aged ≥65 years. After applying selection criteria, 39,186 new users were considered for data analysis: 1) 2,639, 5,708, and 16,798 new users in the antihyperlipidemic cohort for Italy, Spain, and Ireland, respectively; 2) 730, 1,837, and 4,482 new users in the antiosteoporotic cohort for Italy, Spain, and Ireland, respectively; and 3) 1,226, 2,413, and 3,353 new users in the oral antidiabetic cohort for Italy, Spain, and Ireland, respectively. Details on the number of patients excluded per the exclusion criteria are reported in . describes patient characteristics for each drug class across the three European cohorts. There were differences in the distribution of patients’ age across the three European cohorts, in the drug categories of interest. The Spanish cohort had a similar distribution between patients aged 65–74 years and patients aged 75–84 years (46.7 vs 43.0 and 42.2 vs 43.8, respectively, in antiosteoporotic and oral antidiabetic medication use), while the Italian and Irish cohorts showed a higher percentage of patients aged 65–74 years than patients aged 75–84 years (53.7 vs 38.5 and 58.0 vs 28.9, respectively, in the antiosteoporotic category; 61.9 vs 32.1 and 72.7 vs 21.0, respectively, in the antidiabetics category). All three countries had a higher percentage of new users aged 65–74 years than new users aged 75–84 years for antihyperlipidemic medications (59.1 vs 34.6 Italian cohort; 50.9 vs 39.4 Spanish cohort; 70.6 vs 22.7 Irish cohort). In particular, the Irish cohort had the highest percentage of new users aged 65–74 years in all three classes of drugs.

Table 2 Demographic characteristics of new users for each drug category included in the Italian, Spanish, and Irish cohorts

Implementation

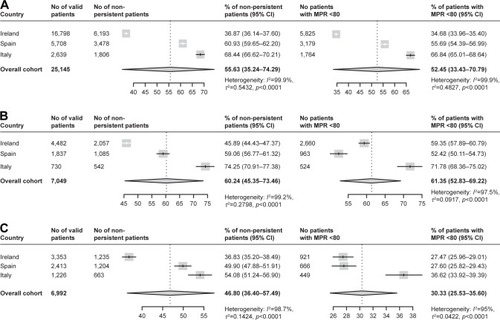

The percentage of patients with suboptimal implementation of treatment, calculated as MPR <80%, over a 12-month follow-up period was: 1) 34.68%, 55.69%, and 66.84%, respectively, for the Irish, Spanish, and Italian cohorts for antihyperlipidemic users; 2) 59.35%, 52.42%, and 71.78%, respectively, for the Irish, Spanish, and Italian cohorts for antiosteoporotic drug users; and 3) 27.47%, 27.60%, and 36.62%, respectively, in the Irish, Spanish, and Italian cohorts for oral antidiabetic drugs users (). The proportion of nonadherence (MPR <80%) in the pooled data from the three countries was 52.45% (95% CI: 33.43–70.79, I2 =99.9%, p<0.0001) for antihyperlipidemics, 61.35% (95% CI: 52.83–69.22, ICitation2 =97.5%, p<0.0001) for antiosteoporotics, and 30.33% (95% CI: 25.53–35.60, ICitation2 =95%, p<0.0001) for oral antidiabetics (). In the pooled analysis, the odds of nonadherence (MPR <80%), during 12-months, post-index period were significantly higher for patients aged ≥85 years than that of the comparison group (ie, patients aged 65–74 years) in the three drug categories (OR 1.43, 95% CI: 1.12–1.83 for antihyperlipidemics; OR 1.41, 95% CI: 1.17–1.70 for antiosteoporotics; OR 1.63, 95% CI: 1.07–2.47 for oral antidiabetics); no difference was observed for gender ().

Figure 2 Proportion of discontinuation (non-persistence) and proportion of nonadherence (MPR <80%) in the pooled data from the three countries for (A) antihyperlipidemics, (B) antiosteoporotics, and (C) oral antidiabetics.

Table 3 Odds of discontinuation (non-persistence) and nonadherence (MPR <80%) during the 12-months, post-index date: pooled analysis

Details on nonadherence rates by age groups and by country are reported in .

Discontinuation (non-persistence)

As shown in , at 1-year post-index, with the application of a 60-day refill grace period, the proportion of treatment discontinuation was 1) 36.87%, 60.93%, and 68.44%, respectively, in the Irish, Spanish, and Italian cohorts for antihyperlipidemic drug users; 2) 45.89%, 59.06%, and 74.25%, respectively, in the Irish, Spanish, and Italian cohorts for antiosteoporotic drug users; and 3) 36.83%, 49.90%, and 54.08%, respectively, in the Irish, Spanish, and Italian cohorts for oral antidiabetic drug users. The proportion of treatment discontinuation in the pooled data from the three countries was 55.63% (95% CI: 35.24–74.29, I2 =99.9%, p<0.0001) for antihyperlipidemics, 60.24% (95% CI: 45.35–73.46, ICitation2 =99.2%, p<0.0001) for antiosteoporotics, and 46.80% (95% CI: 36.40–57.49, ICitation2 =98.7%, p<0.0001) for oral antidiabetics (). In the pooled analysis, the odds of discontinuation during the 12-month post-index period were significantly higher for patients aged ≥85 years than for the comparison group (ie, patients aged 65–74 years) in the three drug categories (OR 1.36, 95% CI: 1.11–1.68 for antihyperlipidemics; OR 1.45 95% CI: 1.25–1.70 for antiosteoporotics; OR 1.50 95% CI: 1.26–1.78 for oral antidiabetics) (). Details on discontinuation rates by age groups and by country are reported in .

Discussion

Our analysis provides an overview of medication adherence in older populations for three commonly used chronic medications across three European countries according to a common methodology. The drug classes examined were representative of chronic medications used to treat common and costly conditions in older populations. We found that in the first year of treatment, adherence to therapy was suboptimal with >50% of older people nonadherent to antihyperlipidemic and antiosteoporotic medication across the three countries. Almost a third of patients prescribed oral antidiabetic medication had suboptimal implementation of their medication regime and almost half were non-persistent. The implementation and discontinuation rates were not homogeneous among the three European countries. Italy had the highest percentage of suboptimal implementation and non-persistence across all three drug classes, and Ireland had the lowest. The extent of nonadherence to prescribed medications among patients affected by chronic diseases in Italy has previously been reported as 70% while in Ireland 31% of older people have been reported as nonadherent.Citation22–Citation24 In Spain, the nonadherence rate ranges from 36% in the general type 2 diabetic populationCitation16 to 51% in patients aged over 65 years on multiple medications.Citation25

Previous studies and comparability of major findings

To our knowledge, the present study is the first study to measure adherence to a range of chronic medications in older populations across European countries. As discussed above, previous European studies assessing adherence to therapy in older populations have been country/region specific and/or have focused on a single drug class or disease.Citation26–Citation33 Similar rates of nonadherence across the three drug classes have been reported in some US studies. A retrospective analysis of nonadherence in new users of six chronic medication classes, in a nationally representative pharmacy claims database representing one hundred US health care plans, found nonadherence rates of 39% in statins, 40% in bisphosphonates, and 28% in oral antidiabetics.Citation32–Citation34 Another US study, which compared retrospective drug adherence rates among patients with seven different medical conditions, reported nonadherence rates of 34.6% in type 2 diabetes, 39.2% in hypercholesterolemia, and 49.8% in osteoporosis, which are lower than that reported in the current study.Citation35 In addition to a high level of nonadherence within the three countries, there was also a wide variation between the countries. Interestingly, a multi-country study based on data from the European Social Survey, which measured self-reported adherence to patients’ most recently prescribed medication (any medication), showed a relatively high level of adherence (82%) across all countries, but there was substantial variation between European countries.Citation36 The high level of self-reported adherence may be in reference to acute medication, where adherence has been shown to be higher than chronic medication.Citation3,Citation37

Within our multi-country study, the large differences in adherence across countries could not be explained by sociodemographic and socioeconomic variables alone, and further research is required to establish the reason behind these differences. An analysis of systematic reviews of determinants of patient adherence found that medication nonadherence is affected by multiple determinants, including social factors (eg, social support, economic factors), health care-related factors (eg, barriers to health care), condition-related factors, therapy-related factors, and patient-related factors (eg, demographic, health beliefs).Citation38 The variation in adherence in the current study may be explained by a range of such factors including differences in the structure of the health care systems and health insurance systems and differences in disease prevalence and comorbidities. In Italy, after 2001, many regions decided to re-introduce both fixed and variable user charges on drugs using their increased autonomy in order to include the growth of public expenditure, which could have negatively influenced adherence to therapy.Citation39 A retrospective study investigating the effect of co-payments on adherence to chronic therapies among Italian regions showed a negative effect of co-payments on drug compliance, especially in regions with poor health care management, organization, and financing such as Campania.Citation40,Citation41 Differences in chronic care programs in individual countries may also impact adherence. The Italian health system does not provide pharmaceutical care services for chronic patients, while in Ireland, the national clinical care program for diabetes may support older patients in adhering to their treatment, and in Spain, pharmaceutical care services are provided for chronic patients.Citation42 The variation between the three countries may also reflect cultural differences in patient attitudes or beliefs toward medication taking. Furthermore, the country heterogeneity of nonadherence to medication may depend on more general factors such as how effectively national health care systems address aspects of prevention and health literacy. A systematic review of barriers to medication adherence in older populations in the US found that lack of disease-related knowledge and health literacy were associated with nonadherence.Citation43,Citation46

Adherence was lower in the older age groups (≥85 years) across all three countries. These findings are inconsistent with previous research which has shown that adherence increases with age.Citation36 Increasing age has been shown to be a significant predictor of increased adherence to statins, antihypertensives, and antidiabetics.Citation44,Citation45 However, adherence to these medication classes has been shown to increase with age only up to a certain point, with those aged <75 years likely to be more adherent than older patients.Citation44,Citation45 Older age is associated with increased morbidity, frailty, and cognitive impairment, which can result in decreased adherence and augmented discontinuation among older adults.Citation47 Polypharmacy, which is also more prevalent in older populations, has been shown to decrease adherence.Citation48

Multi-country database studies

A high value of combining diverse health-related databases for drug utilization research is the ability to evaluate medication adherence by applying the same criteria in terms of both data selection and analysis to all the databases involved. This represents an enhancement compared with classic meta-analysis because it helps in reducing biases in data extraction and management. Database networks present an opportunity for a better understanding of medication adherence and health care management across countries that differ in terms of their health care policies and the ability to compare and evaluate the impact of health care policies on patient behaviors and health outcomes. Future research could adopt a similar methodology to investigate the clinical implications of chronic disease nonadherence in older populations across countries and estimate the impact on health service use and cost. The authors faced two main challenges during this study: the first one was in relation to the setup of the shared data model, with the aim to be comprehensive, in terms of the information gathered from the partners, while also ensuring that the data were comparable. The second challenge was in monitoring the partners to ensure that they were following the same analysis protocol. Both these goals were achieved through an intensive exchange of information sharing among the partners, and one recommendation for future similar studies is to establish strong communication among partners and clear documentation of processes and checklists.

Strengths and limitations

Although the methodology described in this work may not technically be defined as a meta-analysis, it nevertheless has permitted work on harmonized data that share the same methodology, thus avoiding ethical issues related to privacy of data. Being an explorative study, the criteria used for the analysis were intentionally simplified to facilitate achieving consensus among the partners. Indeed, we investigated only adherence to monotherapy excluding more complex patterns of treatment. To have a uniform methodology, we defined a core data set, which lacked information on clinical data, comorbidities, complications, and side effects, which could have influenced our results. The database employed included population cohorts in Italy and Spain and older patients with a medical card in Ireland. Nevertheless these databases have been widely used in pharmaco-epidemiological studies at a national level to inform health care policy.

This study used MPR as a measure of suboptimal implementation and thus may have overestimated adherence as patients may not have taken all medications dispensed. Furthermore, although MPR <80% cutoff is widely used in adherence research, it is an arbitrary number, and whether it is clinically important or not depends on many different factors and may be different for different drug classes.

For the assessment of persistence, patients with at least one discontinuation episode were considered nonpersistent. However, an intrinsic limitation of retrospective database analyses, such as this one, is that we are unable to track the reason for the discontinuation, for example, whether discontinuation was recommended by the clinician (eg, a temporary suspension due to an adverse reaction). It should also be noted that pharmacy refill records only provide details on whether or not the patients were dispensed their medication and do not provide details on whether or not the patients actually ingested their medications.

A further limitation includes the limited availability of data at the time of the study (from 2010 to 2011). The limited number of countries involved in the analysis also did not allow us to perform a meta-regression to explore the source of high heterogeneity found in the pooled analysis. Nonetheless, the use of comprehensive pharmacy record data across the three countries provides an important estimate of medication adherence in European populations in the real-world setting.

This study also applied a rigorous taxonomy of adherence and methodology, and the results clearly demonstrate that it would be feasible to utilize these databases at a cross-country level as a tool to compare and evaluate medication-taking behavior.

Implications of nonadherence

Poor adherence to medication has been estimated to cost ~€125 billion annually to European governments, contributing to an estimated 125,000 deaths each year, and accounts for approximately one-quarter of all admissions to nursing facilities and 10% of hospital admissions.Citation1 It is evident that nonadherence in older populations is a global public health issue and interventions to improve medication-taking behavior need to be informed by comparative adherence studies which estimate the magnitude of nonadherence across both countries and chronic conditions.Citation49,Citation50

Conclusion

This study found variable but uniformly suboptimal medication adherence across three chronic medications in three European cohorts. The proportion of nonadherent older people was lower in Ireland (northern European country) than in Italy and Spain (southern European countries). This provides background information for studies aimed at investigating the factors responsible for these phenomena and for the development of initiatives to improve medication management in older populations in Europe. Common standards for data management in cross-country studies are not established. However, the results of this study provide a valuable proof-of-concept and pave the way for further research in order to identify optimal strategies for cross-country management of medication adherence data.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the A1 Action Group members on Prescription and Adherence to Medical Plans of the European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing for their contributions. Editorial assistance was provided by Dr Melanie Gatt (PhD), an independent medical writer, on behalf of Springer Health care Communications. This was funded by the University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy.

Supplementary materials

Table S1 Nonadherence rates (MPR <80%), in all three drug classes, by age groups and by country

Table S2 Non-persistence rates, in all three drug classes, by age groups and by country

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health OrganizationAdherence to Long-Term Therapies. Evidence for Action2003 Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdfAccessed November 10, 2017

- VrijensBDe GeestSHughesDAA new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medicationsBr J Clin Pharmacol201273569170522486599

- OsterbergLBlaschkeTAdherence to medicationN Engl J Med2005353548749716079372

- GiardiniAMartinMTCahirCToward appropriate criteria in medication adherence assessment in older persons: position paperAging Clin Exp Res201628337138126630945

- CostaEGiardiniASavinMInterventional tools to improve medication adherence: review of literaturePatient Prefer Adherence201591303131426396502

- European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy AgeingA1 Action group 2016–2018 Version9th22016Template for the renovation of the existing Action Plans Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eip/ageing/sites/eipaha/files/library/renovated_action_plan_2016-2018_ag_a1_0.pdfAccessed November 10, 2017

- IllarioMVollenbroek-HuttenMMolloyDWMendittoEIaccarinoGEklundPActive and healthy ageing and independent livingJ Aging Res2015201554218326346624

- MendittoEBolufer De GeaACahirCScaling up health knowledge at European level requires sharing integrated data: an approach for collection of database specificationClinicoecon Outcomes Res2016825326527358570

- Department of Public Expenditure and ReformGeneral Medical Services Scheme2016 Available from: http://www.budget.gov.ie/Budgets/2017/Documents/3.%20General%20Medical%20Services%20Scheme.pdfAccessed November 10, 2017

- OrlandoVGuerrieroFPutignanoDPrescription patterns of antidiabetic treatment in the elderly. Results from Southern ItalyCurr Diabetes Rev201512210010626126718

- ComellaPFrancoLCasarettiREmerging role of capecitabine in gastric cancerPharmacotherapy200929331833019249950

- GrimesTFitzsimonsMGalvinMDelaneyTRelative accuracy and availability of an Irish National Database of dispensed medication as a source of medication history information: observational study and retrospective record analysisJ Clin Pharm Ther201338321922423350784

- Prados-TorresAPoblador-PlouBGimeno-MiguelACohort profile: the epidemiology of chronic diseases and multimorbidity. The EpiChron Cohort StudyInt J Epidemiol2018472382f384f29346556

- WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology and the WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Utilization Research and Clinical Pharmacological ServicesIntroduction to Drug Utilization Research World Health Organization2003 Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/s4876e/s4876e.pdfAccessed November 13, 2017

- KirkmanMSRowan-MartinMTLevinRDeterminants of adherence to diabetes medications: findings from a large pharmacy claims databaseDiabetes Care201538460460925573883

- MaloSAguilar-PalacioIFejaCDifferent approaches to the assessment of adherence and persistence with cardiovascular-disease preventive medicationsCurr Med Res Opin20173371329133628422521

- O’SheaMPTeelingMBennettKAn observational study examining the effect of comorbidity on the rates of persistence and adherence to newly initiated oral antihyperglycaemic agentsPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf201322121336134424142802

- CramerJARoyABurrellAMedication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitionsValue Health2008111444718237359

- HaynesRBA critical review of the “determinants” of patient compliance with therapeutic regimensSackettDLHaynesRBCompliance with Therapeutic RegimensBaltimore, MDJohns Hopkins University Press19762639

- DerSimonianRLairdNMeta-analysis in clinical trialsControl Clin Trials1986731771883802833

- HigginsJPThompsonSGDeeksJJAltmanDGMeasuring inconsistency in meta-analysesBMJ2003327741455756012958120

- MendittoEGuerrieroFOrlandoVSelf-assessment of adherence to medication: a case study in Campania region community-dwelling populationJ Aging Res2015201568250326346487

- NapolitanoFNapolitanoPAngelilloIFMedication adherence among patients with chronic conditions in ItalyEur J Public Health2016261485226268628

- CahirCFaheyTTeljeurCBennettKMedication taking behaviour and adverse health outcomes in community dwelling older patientsISPE conference presentationDublin2016

- MaloSAguilar-PalacioIFejaCPersistence with Statins in Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Findings From a Cohort of Spanish WorkersRev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed)2018711263228473266

- BennerJSGlynnRJMogunHNeumannPJWeinsteinMCAvornJLong-term persistence in use of statin therapy in elderly patientsJAMA2002288445546112132975

- CasulaMCatapanoALPiccinelliRAssessment and potential determinants of compliance and persistence to antiosteoporosis therapy in ItalyAm J Manag Care2014205e138e14525326928

- IolasconGGimiglianoFOrlandoVCapaldoADi SommaCMendittoEOsteoporosis drugs in real-world clinical practice: an analysis of persistenceAging Clin Exp Res201325Suppl 1S137S14124046038

- WalkerEAMolitchMKramerMKAdherence to preventive medications: predictors and outcomes in the Diabetes Prevention ProgramDiabetes Care20062991997200216936143

- WeyckerDMacariosDEdelsbergJOsterGCompliance with drug therapy for postmenopausal osteoporosisOsteoporos Int200617111645165216862397

- IolasconGGimiglianoFMorettiARates and reasons for lack of persistence with anti-osteoporotic drugs: analysis of the Campania region databaseClin Cases Miner Bone Metab2016132126129

- ScalaDMendittoEArmellinoMFItalian translation and cultural adaptation of the communication assessment tool in an outpatient surgical clinicBMC Health Serv Res20161014679686

- CorettiSRomanoFOrlandoVEconomic evaluation of screening programs for hepatitis C virus infection: evidence from literatureRisk Manag Healthc Policy20158455425960681

- YeawJBennerJSWaltJGSianSSmithDBComparing adherence and persistence across 6 chronic medication classesJ Manag Care Pharm200915972874019954264

- BriesacherBAAndradeSEFouayziHChanKAComparison of drug adherence rates among patients with seven different medical conditionsPharmacotherapy200828443744318363527

- LarsenJStovringHKragstrupJHansenDGCan differences in medical drug compliance between European countries be explained by social factors: analyses based on data from the European Social Survey, round 2BMC Public Health2009914519445714

- KardasPPatient compliance with antibiotic treatment for respiratory tract infectionsJ Antimicrob Chemother200249689790312039881

- KardasPLewekPMatyjaszczykMDeterminants of patient adherence: a review of systematic reviewsFront Pharmacol201349123898295

- FranceGTaroniFDonatiniAThe Italian health-care systemHealth Econ200514Suppl 1S187S20216161196

- AtellaVKopinskaJAThe impact of cost-sharing schemes on drug compliance in Italy: evidence based on quantile regressionInt J Public Health201459232933924336975

- MendittoEOrlandoVCorettiSDoctors commitment and long-term effectiveness for cost containment policies: lesson learned from biosimilar drugsClinicoecon Outcomes Res2015117575581

- Estrategia en Diabetes del SistemaNacional de Salud. Actualización. SANIDAD2012Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad Available from: http://www.msps.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/pdf/excelencia/cuidadospaliativos-diabetes/DIABETES/Estrategia_en_diabetes_del_SNS_Accesible.pdfAccessed November 10, 2017

- GelladWFGrenardJLMarcumZAA systematic review of barriers to medication adherence in the elderly: looking beyond cost and regimen complexityAm J Geriatr Pharmacother201191112321459305

- IshisakaDYJukesTRomanelliRJWongKSSchiroTADisparities in adherence to and persistence with antihypertensive regimens: an exploratory analysis from a community-based provider networkJ Am Soc Hypertens20126320120922520931

- SharmaKPTaylorTNPharmacy effect on adherence to antidiabetic medicationsMed Care201250868569122354211

- GibsonTBMarkTLMcGuiganKAAxelsenKWangSThe effects of prescription drug copayments on statin adherenceAm J Manag Care200612950951716961440

- InselKMorrowDBrewerBFigueredoAExecutive function, working memory, and medication adherence among older adultsJ Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci2006612P102P10716497953

- HugtenburgJGBlomATKisoensinghSUInitial phase of chronic medication use; patients’ reasons for discontinuationBr J Clin Pharmacol200661335235416487231

- BousquetJBewickMCanoABuilding bridges for innovation in ageing: synergies between action groups of the EIP on AHAJ Nutr Health Aging20172119210427999855

- IllarioMVollenbroek-HuttenMMMolloyDWActive and healthy ageing and independent living 2016J Aging Res20162016806207927818798

- Ministry of Health. Italian Medicines AgencyCircolare AIFA del 3 agosto2007 Available from: http://xoomer.virgilio.it/pgiuff/osservazionali.pdfAccessed May 2017

- SinnottSJBennettKCahirCPharmacoepidemiology resources in Ireland-an introduction to pharmacy claims dataEur J Clin Pharmacol201773111449145528819675