Abstract

Background

There are ethno-cultural differences in cardiac patients’ adherence to medications. It is unclear why this occurs. We thus aimed to generate an in-depth understanding about the decision-making process and potential ethno-cultural differences, of white, Chinese, and south Asian cardiac patients when making the decision to adhere to a medication regimen.

Methods

A hierarchical descriptive decision-model was generated based on previous qualitative work, pilot tested, and revised to be more parsimonious. The final model was examined using a novel group of 286 cardiac patients, using their self-reported adherence as the reference. Thereafter, each node was examined to identify decision-making constructs that might be more applicable to white, Chinese or south Asian groups.

Results

Non-adherent south Asians were most likely to identify a lack of receipt of detailed medication information, and less confidence and trust in the health care system and health care professionals. Both Chinese and south Asian participants were less likely to be adherent when they had doubts about western medicine (eg, the effects and safety of the medication). Being able to afford the cost of medications was associated with increased adherence. Being away from home reduced the likelihood of adherence in each group. The overall model had 67.1% concordance with the participants’ initial self-reported adherence, largely due to participants’ overreporting adherence.

Conclusion

These identified elements of the decision-making process are generally not considered in traditionally used medication adherence questionnaires. Importantly these elements are modifiable and ought to be the focus of both interventions and measurement of medication adherence.

Introduction

The two largest visible minority groups in Canada are Chinese (from China, Hong Kong, Macau, or Taiwan) and south Asians (from India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh or Nepal) and are among the fastest growing.Citation1 Canada’s health care providers will need to develop a strategy to meet the potential care delivery challenges for these groups.

Chinese are among the least likely whereas south Asians are among the most likely ethnic groups to develop heart disease.Citation2–Citation4 Chinese patients have a higher early mortality following a cardiac event than south Asian or white patients, while south Asian and white patients have a greater likelihood of having future cardiac events.Citation5 A number of studies have revealed that south Asians have higher rates of ischemic heart disease deaths relative to Chines or whites.Citation4–Citation8 There is a lack of clarity or consensus regarding why this occurs. It is possible that ethnocultural differences in access to, and delivery of health care may influence management of heart disease and thereby morbidity and mortality outcomes.

Medication adherence has most recently been defined as “the process by which patients take their medications as prescribed”.Citation9 (p696) Adherence to prescribed medications is already a challenge among the general population, and nonadherence is typically influenced by the interaction of several factors. Krousel-Wood et alCitation10 and othersCitation11,Citation12 have identified that patient- (eg, ethnicity, age, socioeconomic status, health beliefs), provider- (eg, sense of reciprocal respect) and health care system-related (eg, access to understandable information, costs) factors affect medication adherence. The disease itself, and the types and numbers of medications may also influence adherence. Coronary artery disease, for example, requires lifestyle modification and often the use of several medications; many of which have their own side effects, thereby increasing the risk of nonadherence.Citation10,Citation11

The majority of patients who suffer a cardiac event will survive the initial event and require chronic (outpatient) management.Citation13,Citation14 The evidence-based management of coronary artery disease includes adhering to cardiac medications as a core therapy to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Adherence to antiplatelet agents, beta blocker, statins and ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocking agents (medications recommended in international cardiovascular guidelines)Citation15,Citation16 is associated with 20%–30% reduction in morbidity and mortality following a cardiac event.Citation15–Citation18 Outside the clinical trial setting, adherence to pharmacotherapy is often poor, thus limiting the extent of therapeutic benefit that can be achieved.Citation9,Citation19,Citation20 The risks of poor adherence are extensive and may result in disease progression, repeated hospitalizations, and death. The collective economic repercussions for medication nonadherence are estimated to exceed $100 billion per year.Citation21

Previous work has shown that Chinese and south Asian cardiac patients are significantly less likely to adhere to their medications,Citation5 and Chinese and south Asian diabetics who are prescribed cardiac medications are also significantly less likely to adhere to their medications relative to their white counterparts.Citation22 These study findings clearly highlight important discrepancies in cardiovascular medication adherence between these three ethno-cultural groups.

Adherence to medications is largely controlled by patients (self-managed). It is unknown how recognized (and yet to be discovered) factors work together or how they are prioritized in the context of patients’ everyday decision-making to take or not to take their medications as prescribed. We aimed to generate a more in-depth understanding about the decision-making process that people with ACS undergo when faced with making therapeutic choices. The results could lay the groundwork to develop and evaluate ethno-culturally sensitive practices that will help to optimize morbidity and mortality reduction in ethnic patients with heart disease.

Methods

Design

We used a three-phased approach to develop and examine a descriptive decision-model that depicts how whites, Chinese and south Asians who have heart disease make the decision to adhere (or not) to their prescribed medications. We used Gladwin’sCitation23 ethnographic decision-tree modeling approach, to describe how people arrive at their decision, and the role that ethno-culture plays in that decision-making. This is a method used primarily by anthropologists and which has been successfully used by health disciplinesCitation24–Citation29 to model group behavior based on individuals’ decision-making. This study protocol received approval from the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Calgary and was undertaken in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964.

Gladwin’sCitation23 decision-tree modeling approach relies on methodological triangulation. Initially, qualitative interviewing strategies are used to generate data that support the inductive work of building the original model (stage A). The interviews focus on learning about the contexts in which, and criteria that, people use to identify and select among available alternatives. The preliminary decision-tree model is developed and refined through quantitatively (survey methods) “pilot testing” (stage B). Thereafter, a quantitative (survey) method is used for determining if the decision-tree model “works” (stage C). Though our aim was not directed at evaluating the model for accuracy, as we were more concerned about examining ethno-cultural differences in how participants respond to the model questions, we examined concordance of the model outcomes with self-reported adherence. The findings from the qualitative interviews have already been published,Citation30 thus the description below focuses on stages B and C.

Sample

There were 286 participants in this study. GladwinCitation23 suggests a sample of approximately 150 when there are multiple groups and outcomes. This sample size is in keeping with our previous work,Citation26,Citation27 as well as that of others,Citation24,Citation25,Citation28,Citation29 who have used this method.

The majority of participants were selected from a cohort of acute coronary syndrome patients who were included in an international study focused on ethnicity and symptoms presentation. Participants of that cohort study were asked if they would agree to be contacted for potential participation in future studies. These potential participants were contacted by telephone to explain the study and the consent process. Written informed consent for this study was obtained by mailing a consent form to the potential participant. Once the consent form was returned to the investigators, the surveys were undertaken by telephone by trained research assistants. After finding difficulty garnering a sample of Chinese participants, we sought additional participants through a Chinese senior’s cultural center. There, we asked attendees if a physician told them that they had heart disease (coronary artery disease), and if they were prescribed more than two medications for their heart disease. If these potential participants answered affirmatively to each question, we invited them to participate, obtained their written informed consent, and conducted the interview in person.

Participants were selected based on their self-identified ethnicity of European-white, Chinese or south Asian and their ability to speak English; Cantonese or Mandarin; or Punjabi or Hindi. There was a greater proportion of male south Asian and Chinese participants, and a greater proportion of non-English speaking south Asian participants who agreed to participate in this study relative to the cohort from which participants were recruited. The Chinese participants in this study were older relative to the cohort from which they were initially recruited because many were recruited from a senior’s center.

Translation

All study materials were rigorously translated and the details are outlined in a previous publication.Citation31 Briefly, study materials were professionally translated, as well as validated by “lay” people who speak and read the languages of interest. This process ensures that study materials are indeed accurate and understandable (eg, not too high or low a reading level). All non-English interviews were undertaken by highly trained research assistants who fluently spoke and read both English as well as the non-English language.

Decision-tree model preliminary testing and refinement, stage B

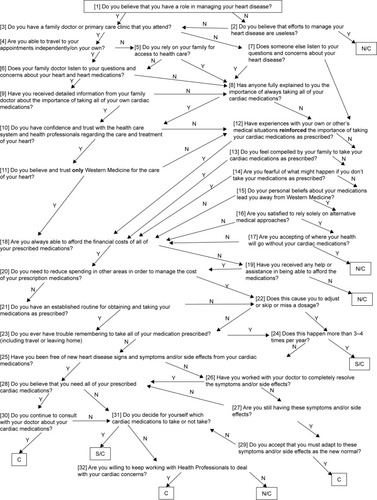

A decision-tree model was developed based on qualitative interviews in stage A.Citation30 This model was hierarchical and comprised a series of yes/no questions. The questions were translated into traditional and simplified Chinese characters as well as Punjabi and Hindi languages, as described above. The preliminary (pilot) testing of this model was undertaken by administering a survey based on the series of questions in the model to a small sample of 59 novel white (n=25), Chinese (n=9) and south Asian (n=25) participants (eg, they had not participated in stage A). We aimed to identify areas where the model was unclear (eg, question needed to be reworded); “failing” to work in interview format; the translation needed revision; or interviewer error was occurring.Citation23 Field notes were taken to document any other issues (eg, difficulty with asking questions in the correct order) that arose during this data collection phase. Following these interviews, a more parsimonious model was developed (see ).

Decision-tree model examination, stage C

Another novel group of participants was recruited to test the final model. First, a short demographic questionnaire was administered to enable characterization of the study sample. These data were analyzed using ANOVA or Chi-square, as appropriate. Then, in keeping with Gladwin’sCitation23 process, the participants were asked to self-report their adherence behavior as: “consistently,” “sometimes” or “not at all” adherent to their cardiac mediations. These three potential outcomes were identified through the qualitative work undertaken in stage A.Citation30 The number of participants whose self-reported adherence matched the outcome of the decision-tree were identified, then divided by the number of participants. This proportion represented the concordance of the self-report with the model outcome. To address our main study aim, we then compared items significantly related to the model outcomes, and item responses based on ethnicity. Chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact tests were used for these analyses. All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.

Results

As seen in , 286 participants (117 white, 79 Chinese, 90 south Asian) were surveyed to test the decision-tree model. There were differences in the demographic characteristics examined by ethnic group. There were significantly more men in the south Asian group than there were in the white and Chinese groups. The Chinese were significantly older than the other participants (possibly due to where a portion of them were recruited) and south Asians are known to develop heart disease at a younger age.Citation32 More than 87% of Chinese surveys and 50% of south Asian surveys were undertaken in languages other than English. The greatest proportion of Chinese and south Asians immigrated to Canada >20 years ago. Significantly more south Asians were married and resided in extended family situations relative to other participants. Significantly more whites were educated beyond high school (or equivalent) than others. Given the age difference, significantly more Chinese were retired relative to their counterparts.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of 286 stage C participants

To examine decision-making process differences between whites, Chinese and south Asian participants, the dichotomous response to each question in the model () was compared to the model outcome response for each ethnic group (see for significant factors). These significant factors are presented here in the order in which they appear in the model. South Asian participants who were not at all adherent to their cardiac medications were most likely to identify that they had not received detailed information from the family doctor about taking their cardiac medications (, Q9). They were also most likely to identify that they did not have confidence and trust in the health care system or health care professionals regarding their treatment (, Q10). Whites who were consistently or sometimes adherent to their cardiac medications tended to believe and trust only western medicine for the care of their heart (, Q11). All study participants who indicated that they could afford the financial costs of their medications tended to be those who consistently or sometimes took their medications (, Q18). Those south Asians who indicated they could not always afford the financial costs, and who indicated that they received assistance to pay for their medications were then more likely to be consistently or sometimes adherent than other south Asians (, Q19). Whites who indicated that they had an established routine for obtaining and taking medications as prescribed were mostly likely to be consistently or sometimes adherent (, Q21). All participants indicated that traveling or leaving home caused some lack of consistency in taking their medications (, Q23) and this happened more than 3–4 times per year (, Q24). Only white participants indicated that being free of heart disease signs and symptoms and/or side effects from their medications led to them being consistent with taking their cardiac medications (, Q25). These white participants were also most likely to accept that they needed to adapt to the signs and symptoms and/or side effects of their medications (, Q29). Chinese and south Asian participants who believed they needed all of their prescribed medications were most likely to consistently take their medications (, Q28). Those participants that were consistently adherent also indicated that they did not decide for themselves which cardiac medications to take or not to take, while those who were sometimes or not adherent did so (, Q31).

Table 2 Factors significantly related to the model outcomes by ethnicityTable Footnotea

To identify questions upon which white, Chinese and south Asian participants significantly differed, we examined each question response relative to the participants’ ethnicity. As seen in , white participants were most likely to respond affirmatively to the question regarding their belief in only western medicine (, Q11). South Asian participants were least likely to identify that they had been free of new heart disease signs and symptoms and/or side effects from their cardiac mediations (, Q25). There were slight differences between groups about whether or not they continued to consult with their doctor about their cardiac medications (, Q30). Whites were most likely to do so, followed by south Asians, then Chinese.

Table 3 How ethnicity affected question responseTable Footnotea

Finally, there were no significant differences between ethnic groups in outcomes based on their self-report or in model outcomes (). The overall concordance of the participants’ self-report of adherence with the model outcomes was 67.1%. The model was most successful with the white participants (69.2%), followed by the Chinese (65.8%), and south Asians (65.6%). There were 94 failures in total. Most failures (55/94) occurred because participants (whites and south Asians more than Chinese) overreported relative to underreported adherence.

Table 4 Self-report and actual model outcomes

Discussion

We used descriptive decision-modeling to develop a more in-depth understanding of the contextual factors that influence how white, Chinese, and south Asian cardiac patients decide to (or not) take their cardiac medications. The model outcomes had a 67.1% concordance with participants’ self-reported adherence to their cardiac medications. We noted that more than half of the instances in which there was a lack of concordance was because the participants tended to over-report as opposed to underreport their adherence, relative to the model outcome. We did not consider the participants’ self-report as a “gold standard” of measurement, yet this finding is consistent with the general and cardiovascular literature focused on medication adherence.Citation33,Citation34

Each participant group (white, Chinese, and south Asian) identified that affordability of medications increased their medication adherence. Though Canada has universal health care, outpatient medications are not part of that benefit. In fact, 10%–12% of Canadians with chronic disease, such as cardio-vascular disease, face financial barriers to managing their illness.Citation35,Citation36 Having a financial barrier to accessing medications has a detrimental effect on health. Campbell et alCitation37 showed that after adjustment for relevant demographic variables, chronic disease patients who self-identified having a financial barrier had an increased rate of disease-related hospitalization (incidence rate ratio 1.36 [95% CI: 1.29–1.44]); as well as mortality (incidence rate ratio 1.24 [95% CI: 1.16–1.32]) compared to those without financial barriers. Having a financial barrier to care is a central construct in this model (all but one participant’s path through the model lead to this question) and leads to detrimental outcomes.

Each participant group also identified that challenges in remembering to take their medications, especially while traveling or being away from home put them at risk for nonadherence. Medication adherence can be positively influenced by developing regular routines (though this related to the model outcomes only for the white participants). Costa et alCitation38 identified that comprehensive self-management programs can improve medication adherence in some patients with chronic illness, but this has not been shown conclusively in patients with cardiovascular disease. They posited that the reason for a lack of significant success in enhancing medication adherence is interventions often lack a strong behavior theory basis. Our earlier qualitative work revealed that Chinese and south Asian patients, in particular, travel for extended periods of time and rely heavily on their pharmacist to assist in ensuring that sufficient medication is dispensed. Thereafter having a regular routine in taking medications enhanced adherence.Citation30

The model revealed that south Asians participants believed that having good communication with health care provider regarding their medications was an important factor in their adherence. In a related item, having decreased confidence in their health care provider negatively influenced adherence.

A systematic review by Sohal et alCitation39 revealed that “language and communication discordance with the health care provider” (p. 7) played an important role in reducing south Asian’s capacity to understand information critical to adhering to their diabetes medications. The review also revealed that south Asian diabetic patients tended to want to follow their physician’s advice and be adherent, but when lack of communication and mistrust ensued, adherence was decreased. The qualitative work by Ens et alCitation40 also revealed that “relationships with health care professionals who demonstrated clear communication and cultural awareness was associated with enhanced medication adherence” (p. 1472). Indeed, we found for all patients in our foundational qualitative work, that physician’s communication was central to adherence for all participants.Citation30

Having some doubt about the need to take all of the prescribed cardiac medications was associated with variability in medication adherence in Chinese and south Asian participants. Our earlier qualitative work revealed that Chinese and south Asian cardiac patients took medications with the hope of being able to reduce or quit taking medications in the future.Citation30 Further, the systematic review by Sohal et alCitation39 identified that concerns about “long-term safety” were also central to south Asians’ adherence. Indeed, Li and FroelicherCitation41 also identified that Chinese were less likely to adhere to hypertension medications when they had a lower perceived benefit from taking the medication. Furthermore, differences in health beliefs (eg, viewing disease as a result of fate and preferring self-management over medical visits) are associated with poor adherence to treatment recommendations.Citation42

Finally, there were central elements to this inductively generated decision-model that are not currently included in medication adherence scales and may warrant inclusion in further study of medication adherence. Indeed, patients’ medication adherence occurs as a result of complex factors,Citation10–Citation12 and not merely having a routine. This study has revealed that having financial barriers to accessing medications, being able to communicate effectively with the health care provider (eg, physician, pharmacist), and believing in western medicine (eg, the effectiveness and safety of the medication) are additional factors that ought to be considered.

There were limitations to this study. The characteristics of the study sample do not necessarily reflect those whites, Chinese and south Asians who are from the general population (and meet inclusion criteria). For example, there was an obvious gender imbalance in the south Asian group. It is not uncommon to have difficulty recruiting south Asian women into studies as they are less likely to speak English than men and are often more protected by their family members against intrusion.Citation43 Also, the Chinese participants were older than expected. This is likely due to participant recruitment from a senior’s cultural center. There is no mechanism using Gladwin’sCitation23 methods to control for these differences. Thus, these study findings may lack some generalizability.

Conclusion

It has not been clear why there are ethno-cultural differences in cardiac patients’ adherence to medications. Key elements associated with adherence for all participants included affordability of the medications and creating a routine (eg, remembering). South Asian participants were less likely to be adherent when they did not perceive having “good” communication with their health care provider (eg, physician, pharmacist). Both Chinese and south Asian participants were less likely to be adherent when they had doubts about western medicine (eg, the effects and safety of the medication). These elements of the decision-making process are not included in the traditionally used medication adherence questionnaires. Importantly these elements are modifiable and ought to be the focus of both interventions and measurement of medication adherence.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Kathryn King-Shier is funded by the Guru Nanak Dev Ji DIL Research Chair.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- CanadaSNational Household Survey2011 Available from: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/dttd/Rpeng.cfm?LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=0&GK=0&GRP=0&PID=105470&PRID=0&PTYPE=105277&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2013&THEME=95&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=Accessed August 17, 2018

- LiHGeJCardiovascular diseases in China: current status and future perspectivesIJC Heart Vasculature20156253128785622

- RanaAde SouzaRJKandasamySLearSAAnandSSCardiovascular risk among South Asians living in Canada: a systematic review and meta-analysisCMAJ Open201423E183E191

- YusufSReddySOunpuuSAnandSGlobal burden of cardiovascular diseases: Part I: General considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanizationCirculation2001104222746275311723030

- KhanNAGrubisicMHemmelgarnBOutcomes after acute myocardial infarction in South Asian, Chinese, and white patientsCirculation2010122161570157720921444

- ReddyKSYusufSEmerging epidemic of cardiovascular disease in developing countriesCirculation19989765966019494031

- ShethTNairCNargundkarMCardiovascular and cancer mortality among Canadians of European, south Asian and Chinese origin from 1979 to 1993: an analysis of 1.2 million deathsCan Med Assoc J1999161213213810439820

- Tunstall-PedoeHKuulasmaaKMähönenMTolonenHRuokokoskiEAmouyelPContribution of trends in survival and coronary-event rates to changes in coronary heart disease mortality: 10-year results from 37 WHO MONICA project populations. Monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular diseaseLancet199935391641547155710334252

- VrijensBde GeestSHughesDAA new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medicationsBr J Clin Pharm2012735691705

- Krousel-WoodMThomasSMuntnerPMoriskyDMedication adherence: a key factor in achieving blood pressure control and good clinical outcomes in hypertensive patientsCurr Opin Cardiol200419435736215218396

- OsterbergLBlaschkeTAdherence to medicationN Engl J Med Overseas Ed20053535487497

- BanningMA review of interventions used to improve adherence to medication in older peopleInt J Nurs Stud200946111505151519394018

- LiemSSvan der HoevenBLOemrawsinghPVMISSION!: optimization of acute and chronic care for patients with acute myocardial infarctionAm Heart J2007153114e1

- TownsendNNicholsMScarboroughPCardiovascular disease in Europe – epidemiological update 2015Eur Heart J201536402696270526306399

- O’GaraPTKushnerFGAscheimDDACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice GuidelinesJ Amer Coll Cardiol2013614e78e14023256914

- IbanezBJamesSAgewallS2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Euro Heart J2018392119177

- Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators; YusufSSleightPPogueJEffects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patientsN Engl J Med2000342314515310639539

- Heart Protection Study Collaborative GroupMRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trialLancet2002360932672212114036

- SackettDLSnowJCThe magnitude of adherence and nonadherenceHaynesRBTaylorDWSackettDLCompliance in Health Care11Baltimore, MAJohns Hopkins University Press1979

- SabateEAdherence to Long-term Therapies: Evidence for ActionGenevaWorld Health Organization2003 http://www.who.int/chronic_conditions/en/adherence_report.pdf

- RasmussenJNChongAAlterDARelationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarctionJAMA2007297217718617213401

- ChongEWangHKing-ShierKMPrescribing patterns and adherence to medication among South-Asian, Chinese and white people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort studyDiabet Med201431121586159325131338

- GladwinCHEthnographic Decision-tree ModelingNewbury Park, CASage Publications1989

- BeckKAEthnographic decision tree modeling: a research method for counseling psychologyJ Couns Psychol2005522243249

- OhHSParkHADecision tree model of the treatment-seeking behaviors among Korean cancer patientsCancer Nurs200427425926615292720

- King-ShierKMQuanHMatherCUnderstanding coronary artery disease patients’ decisions regarding the use of chelation therapy for coronary artery disease: descriptive decision modelingInt J Nurs Stud20124991074108322534492

- King-ShierKMMatherCMLeblancPUnderstanding the influence of urban- or rural-living and cardiac patient’s decisions about diet and exerciseIntern J Nurs Stud20135015131523

- MathewsHFHillCEApplying cognitive decision theory to the study of regional patterns of illness treatment choiceAm Anthropol1990921155170

- MontbriandMJDecision tree model describing alternate health care choices made by oncology patientsCancer Nurs19951821041177720049

- King-ShierKMSinghSKhanNAEthno-cultural considerations in cardiac patients’ medication adherenceClin Nurs Res201726557659127121478

- KingKMKhanNLeblancPQuanHExamining and establishing translational and conceptual equivalence of survey questionnaires for a multi-ethnic, multi-language studyJ Adv Nurs201167102267227421535093

- GuptaMBristerSVermaSIs South Asian ethnicity an independent cardiovascular risk factor?Can J Cardiol200622319319716520847

- LamWYFrescoPMedication adherence measures: an overviewBiomed Res Int20152015112

- HoPMBrysonCLRumsfeldJSMedication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomesCirculation2009119233028303519528344

- CampbellDKing-ShierKHemmelgarnBThe association between financial barriers and care and outcomes for patients with chronic diseaseHealth Report2014255312 (Statistics Canada Catalogue No 82-003-X).

- LawMRChengLDhallaIAThe effect of cost on adherence to prescription medications in CanadaCan Med Assoc J2012184329730222249979

- CampbellDJMannsBJWeaverRGFinancial barriers and adverse clinical outcomes among patients with cardiovascular-related chronic diseases: a cohort studyBMC Med20171513328196524

- CostaEGiardiniASavinMInterventional tools to improve medication adherence: review of literaturePat Pref Adher2015913031314

- SohalTSohalPKing-ShierKMKhanNABarriers and facilitators for type-2 diabetes management in South Asians: a systematic reviewPLoS One2015109e013620226383535

- EnsTASeneviratneCJonesCKing-ShierKMFactors influencing South Asian cardiac patients’ compliance to their medication regimenIntern J Nurs Stud2014511114721481

- LiWWFroelicherESGender differences in Chinese immigrants: predictors for antihypertensive medication adherenceJ Transcult Nurs200718433133817911573

- LiWWStottsNAFroelicherESCompliance with antihypertensive medication in Chinese immigrants: cultural specific issues and theoretical applicationRes Theory Nurs Pract200721423625418236769

- QuayTAFrimerLJanssenPALamersYBarriers and facilitators to recruitment of South Asians to health research: a scoping reviewBMJ Open201775e014889