Abstract

Background

Media representation of vaccine side effects impacts the success of immunization programs globally. Exposure to the media can cause individuals to feel hesitant toward, or even refuse, vaccines. This study aimed to explore the impact of the media on beliefs and behaviors regarding vaccines and vaccine side effects in an urban clinic in Vietnam.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in an urban vaccination clinic in Hanoi, Vietnam from November 2015 to March 2016. The primary outcomes of this study were the decisions of Vietnamese subjects after hearing about adverse effects of immunizations (AEFIs) in the media. Socio-demographic characteristics as well as beliefs regarding vaccination were also investigated. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with subjects’ behaviors regarding vaccines.

Results

Among 429 subjects, 68.2% of them said they would be hesitant about receiving vaccines after hearing about AEFIs, while 12.4% of subjects said they would refuse vaccines altogether after hearing about AEFIs. Wealthy individuals (OR=0.41; 95% CI=0.19–0.88), and those who displayed trust in government-distributed vaccines (OR=0.20; 95% CI=0.06–0.72) were less likely to display hesitancy regarding vaccination. Receiving information from community health workers (OR=0.44; 95% CI=0.20–0.99) and their relatives, colleagues, and friends (OR=0.47; 95% CI=0.25–0.88) was negatively associated with vaccine hesitancy, but facilitated vaccine refusal after reading about AEFIs in the media (OR=3.12; 95% CI=1.10–8.90 and OR=3.75; 95% CI=1.56–9.02, respectively).

Conclusion

Our results reveal a significantly high rate of vaccine hesitancy and refusal among subjects living in an urban setting in Vietnam, after hearing about AEFIs in the media. Vietnam needs to develop accurate information systems in the media about immunizations, to foster increased trust between individuals, health care professionals, and the Vietnamese government.

Introduction

Vaccines are widely accepted as one of the most important medical achievements of modern civilization. Researchers in many countries have emphasized the cost-effectiveness of vaccination in preventing diseases, especially in developing countries.Citation1–Citation3 Annually, immunizations prevent about 2–3 million deaths worldwide.Citation4 To ensure its protective benefits, vaccine coverage has to reach between 80% to 100% of a given population, depending on the vaccine and the disease that it is preventing.Citation5 Because of the effects of herd immunity, individuals choosing not to vaccinate themselves or their children are unlikely to become infected by a particular disease if they are living in environments where the majority of individuals have been fully vaccinated against it. Conversely, individuals who do receive immunizations remain at risk of acquiring a disease in regions where there has not been sufficient vaccine coverage.Citation6 Consequently, there is a higher mortality rate from infections in those areas where vaccine uptake is low, as opposed to what is seen in areas where large segments of the population adhere to recommended vaccine schedules.Citation7

Nevertheless, public confidence in vaccines is increasingly lost. There has been an increasing number of people beginning to question the safety of vaccines, altering recommended vaccination schedules, or even refusing vaccines altogether.Citation8–Citation10 The term “vaccine-hesitant individuals” has been used to refer people who ignore some vaccines but accept other vaccines, or those who obtain immunizations on an altered/delayed schedule. Vaccine-hesitant individuals do not completely accept nor completely refuse vaccines.Citation10 Larson et alCitation9 found that socio-economic status, the information relayed in the media, attitudes and motivations regarding health protection, and knowledge and awareness of the need for vaccines were each associated with vaccine hesitancy.

The media has contributed significantly to the widespread public distrust of vaccines in many countries worldwide, and Vietnam is no exception.Citation11 In Vietnam, as with other countries globally, individuals receive their news through newspapers, television, and, in recent years, the Internet and social media. Indeed, dissemination of negative information about immunizations has been increased by the advancement of websites such as Facebook and Twitter.Citation11–Citation13 Research worldwide demonstrates that media exposure might facilitate behavior change,Citation14,Citation15 such as increasing the odds of parents bringing their children in for vaccines.Citation16,Citation17 However, the media can also be used by anti-vaccination groups to drive people to oppose vaccines, by raising skepticism about the scientific evidence regarding the risks and benefits of vaccines.Citation11,Citation18 Li et alCitation19 found that public perception of and willingness to receive vaccines dropped dramatically in Vietnam after the media advertised potential side effects of one particular vaccine, described in more detail below. In China, many people lost confidence in the hepatitis B vaccine after media coverage of possible adverse side effects related to the vaccine.Citation20 Capanna et alCitation21 investigated the negative effects of mass media on influenza vaccine coverage in Italy and discovered a 6% to 18% decline in vaccine coverage as a result of media events taking place in 2013–2014. Evidence in Taiwan and Canada also supported the argument that hearing negative stories in the mass media was a possible barrier to individuals receiving vaccinations.Citation22,Citation23

The Vietnamese Government has been implementing a national vaccination program called the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) since 1981. To date, among eleven vaccines used in the EPI, ten vaccines can be manufactured in Vietnam. All children under the age of 6 are eligible to receive vaccines through EPI.Citation24 After implementation of EPI, Vietnam has achieved many vaccine-related milestones, such as becoming polio-free in 2000 and eliminating maternal and neonatal tetanus in 2005.Citation25,Citation26 A recent estimate by the World Health Organization indicated that 96% of the population is covered by the diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine; and that 99% of the population received the first measles vaccine, with 95% of the population receiving the second dose.Citation27 However, these successes have been threatened by the media’s reporting of Adverse Events Following Immunization (AEFIs),Citation19 which refers to “any untoward medical occurrence which follows immunization and which does not necessarily have a causal relationship with the usage of the vaccines”.Citation28 In 2007, many Vietnamese newspapers highly criticized some AEFIs of the hepatitis B vaccine that happened in several vaccination clinics nationwide, including one infant suffering allergy reactions and three fatal cases within a few hours after the vaccination in the period of more than ten days.Citation29 This issue contributed to a significant decline in hepatitis B vaccination coverage in Vietnam, from 64.3% to 26.9% over the next few years.Citation19

Another example is the Quinvaxem vaccine – a pentavalent vaccine (diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, hepatitis B, haemophilus influenza type B),Citation30 which was delivered freely via the EPI in Vietnam with financial assistance from the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI). In 2013, a few AEFIs were reported after infants received the Quinvaxem vaccine, raising considerable public concern about the vaccine’s safety. Specifically, concerns were raised about both fatal and non-fatal reactions to the vaccine, ranging from allergies, seizures, and reduced muscle tone to the death of young infants shortly after receiving the vaccine.Citation31 Controversies between the benefits and drawbacks of Quinvaxem were triggered in many print and internet-based Vietnamese newspapers, and there were also several discussions about the safety of the vaccine on social network sites (eg, Facebook). The Vietnamese Ministry of Health hired the World Health Organization to investigate these AEFIs. The WHO confirmed that although some of the allergic and other non-fatal AEFIs might have been linked to vaccine reactions, the reasons for the fatal AEFIs and many of the non-fatal AEFIs were not related to Quinvaxem and were purely coincidental.Citation31 Despite this news, public trust was lost, and parents decided not to allow their children to receive Quinvaxem. Parents instead chose to wait for Pentaxim (Sanofi Pasteur, Lyon, France) – another pentavalent vaccine that was manufactured in France.Citation32 However, a shortage of the latter vaccine led to the reductions of coverage of immunizations in Vietnamese infants from 99% to 83% for diphtheria-tetanus-whooping cough, and from 76% to 56% for hepatitis B birth dose between 2012 and 2013.Citation27 Li et alCitation19 used mathematical models to project that because of this decline in vaccination coverage, more than 90,000 infections with hepatitis B and approximately 17,500 deaths might occur.

The media has a large impact on Vietnamese citizens’ beliefs regarding vaccines. However, to date, there has been little research published regarding the ways that people’s perceptions of vaccines change as a result of the media in Vietnam. The purpose of this study was to explore the impact of the media on people’s beliefs and behaviors regarding vaccines and vaccine side effects in an urban clinic in Vietnam.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

Study documents were approved by the institutional review board of the Hanoi Medical University. Subjects were introduced to the purpose of this study and asked to give written informed consent if they agreed to participate. Participants could withdraw at any time. Their information remained confidential.

Study setting and sampling method

A cross-sectional study was conducted from November 2015 to March 2016 in an urban vaccination clinic located in the center of Hanoi, the capital city of Vietnam. This clinic is a typical vaccination clinic in urban Vietnam, functioning as a standalone site affiliated with a medical institution (Hanoi Medical University Hospital) and providing walk-in services for people living in the city. The primary subjects at this clinic are parents and their children. In addition, vaccines for the adult population were also available such as human papilloma-virus (HPV) or vaccines for pregnancies. The clinic does more than 25,000 vaccinations per year. This clinic provides vaccines to patients using both the EPI model (free-of-charge) and a for-profit model (where subjects have to pay for vaccines). Therefore, the clinic serves subjects with different income backgrounds. For this study, we chose to look at individuals with children of a variety of age ranges rather than focusing solely on parents with young children, because children in Vietnam receive vaccinations up to the age of 15.Citation24

People were recruited if they met the following eligibility criteria: 1) currently using services in the clinic for themselves and/or their children; 2) 18 years old; 3) able and willing to participate in this study, verified with written informed consent; and 4) able to answer a questionnaire in 15–20 minutes. All eligible subjects were invited to enroll in the study, and asked to give their written informed consent if they agreed to participate. We invited them to a private room of the clinic to ensure confidentiality and to create a safe and comfortable atmosphere for the interview.

We calculated our study’s sample size using the World Health Organization’s formula for estimating a proportion with specified relative precision.Citation33 We expected that the rate of subject refusal of vaccines after hearing about AEFIs would be 30% (based on a previous study conducted in ChinaCitation20), with a 95% confidence level and a margin of error of 0.15. This resulted in a minimum sample size of 399 subjects. An extra 10% was added to our sample size to prevent incomplete data, leading to a sample size of 439. Because we could not access the list of subjects attending the clinic for services due to the confidentiality, a convenience sampling approach was applied in this study to recruit the participants. After finishing the data collection phase, 439 subjects were recruited but only data of 429 subjects were included in the final analysis. Ten subjects had to be excluded because they completed less than 50% of the questionnaire. There were no statistically significant differences in socio-demographic characteristics between participants that were included and excluded from the study.

Measurements and instruments

Face-to-face interviews were performed by the data collection team, including undergraduate and post-graduate students in the Public Health field at the Hanoi Medical University. These interviewers were trained carefully by principal investigators about how to use the questionnaire and how to collect the data effectively. They also did a pilot study with 20 subjects first. Thus, they used a consistent approach for how they asked participants the questions in the survey. Our data collection team approached the subjects, asked them questions in the questionnaire, and wrote down the answers in the form of questionnaire. Each subject spent 15–20 minutes answering all questions in the questionnaire. We did not involve health professionals at the clinic in this study in order to prevent any social desirability bias, which might happen when subjects only participate in studies in order to satisfy their health care providers.

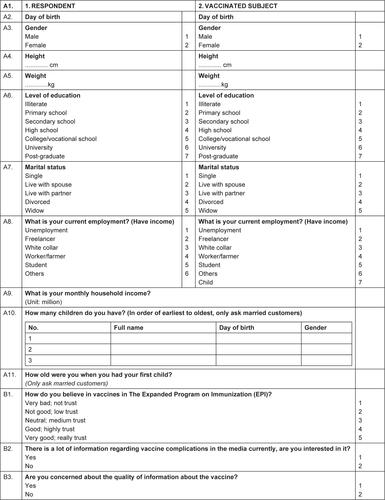

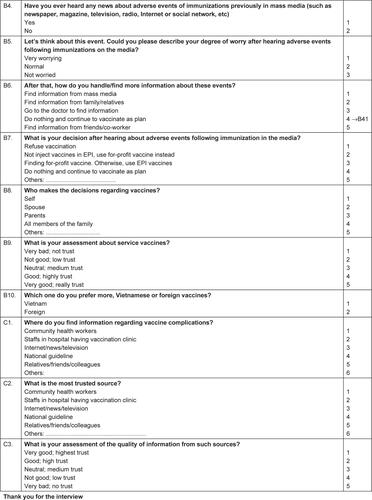

A structured questionnaire was developed and used to collect the data from participants (). In the questionnaire, we first asked subjects to report their demographic characteristics (age, gender, educational attainment, marital status, current occupation, monthly household income and whether they had children under 6 years old). Monthly household income was then divided into five quintiles, from “poorest” to “richest.”

Next, we asked participants a series of questions about the belief of vaccines and reactions with the AEFIs in the media. These questions were developed based on the contextualized factors that we collected from a rapid assessment rather than using an international measure. Subjects’ beliefs regarding EPI and for-profit vaccines were explored using Likert-scales, with five levels ranging from “Very bad, no trust” to “Very good, high trust.” Subjects were also asked about their preferences for the vaccine’s origins (from Vietnam or from foreign countries). In this study, we used the term “EPI vaccines” to refer to the vaccines that belonged to the EPI program (provided freely); and “for-profit vaccines” to refer to the vaccines that were from foreign sources, not from the EPI program and that subjects had to pay for.

Primary outcomes of this study included the behaviors and decisions of subjects after hearing about AEFIs in the Vietnamese media. First, we asked them to recall any AEFIs that they heard or read about in the media. Then, we asked the question “What is your decision regarding vaccination of yourself and/or your child after hearing about adverse events following immunization in the media?” with five answers which included: 1) “Refuse vaccination,” 2) “No injecting EPI vaccines; use for-profit vaccines instead,” 3) “Finding for-profit vaccines; otherwise, use EPI vaccines,” 4) “Do nothing” (eg, continue vaccination as planned), and 5) “Others” (eg, going abroad for vaccination). People who answered (b) or (c) were placed in the “vaccine hesitancy” group.

In this study, we also asked subjects to report the following information: whether they were concerned about information regarding vaccine complications in media, where they got their sources of information about vaccines, what they believed to be the most trusted sources of information about vaccines, whether they were worried after hearing about AEFIs in the media, sources for finding more information about AEFIs, and individual(s) who made decisions regarding vaccines in their family.

Statistical analysis

We used STATA software version 12.0 (Stata Corp. LP, College Station, TX, USA) to analyze the data. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Chi-squared, Student’s t-test, and Mann–Whitney tests were employed to compare the differences of the variables of interest between subjects who were parents bringing their children to receive vaccinations, and adult subjects who were being vaccinated themselves. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to identify factors associated with subjects’ behaviors, comprising “concern about information regarding vaccine complications in media,” “vaccine hesitancy”, and “vaccine refusal” after hearing about AEFIs in the media. Forward stepwise strategies were employed to produce the final reduced models. A threshold P-value of less than 0.2 was used to include the variables into the final models. This threshold was selected to avoid the exclusion of variables that might be meaningful for the interpretation of the model. Multicollinearity was tested using variance inflation factors (VIFs). In the logistic regression, a VIFs value of 2.5 was recommended to be used as a threshold to detect multicollinearity.Citation34

Results

highlights the demographic characteristics of the participants in our study. Among the 429 subjects that participated, the mean age was 26.8 years old (SD=6.2). Most of them visited the clinic to have vaccinations themselves (62.7%). The majority of respondents were female (73.5%), attained more than high school education (63.2%), and were not married (50.6%). About 43.3% and 37.8% of subjects were white-collar workers and students, respectively. Only 33.6% had children under 6 years old. The average monthly income was 15.9 million VND (SD=32.2).

Table 1 Characteristics of respondents

reveals that 50.7% and 86.5% of respondents believed that EPI vaccines and for-profit vaccines were good or very good and could be trusted, respectively. Participants were more likely to trust foreign vaccines (91.0%) than domestic vaccines (29.2%).

Table 2 Attitudes about vaccination services

reveals that most subjects were concerned about vaccine complications reported in the media (90.6%). This concern was higher among parents bringing their children to obtain vaccines than those receiving vaccines themselves (P<0.05). Although most respondents sought information about immunizations via the media (72.4%), staff at hospitals with vaccination clinics were perceived to be the most trustworthy source (38.0%). The results show that most respondents began to worry more about receiving vaccines after hearing about AEFIs in the media (59.6%). Participants also used the media to find additional information about AEFIs (68.9%). A total of 68.2% of subjects hesitated to receive vaccines after hearing about AEFIs in the media, and 12.4% subjects would refuse vaccination.

Table 3 Beliefs about and uptake of vaccines after being exposed to mass mediaTable Footnotea campaigns about vaccine side effects

shows the results of multivariate logistic regression models. VIFs of all variables included in the three models were under 2.5. People were more likely to be concerned about AEFIs in the media if they received more than a high school education (OR=3.07; 95% CI=1.05–8.98); in addition, having children under 6 years old also increased subjects’ concern (OR=15.14; 95% CI=4.34–52.78). Wealthy subjects and those who placed significant trust in for-profit vaccines were less likely to be concerned about AEFIs reported in the media. In addition, people who trusted EPI vaccines were less likely to display vaccine hesitancy. Interestingly, receiving information from community health workers and their relatives, colleagues, and friends had opposing effects when it came to vaccine hesitancy and refusal. Receiving information from these sources was negatively associated with vaccine hesitancy, but positively associated with vaccine refusal.

Table 4 Factors associated with concern about vaccination information in the media and uptake of vaccination services among subjects

Discussion

Our study, one of the first of its kind to investigate media influence on perceptions of vaccines among adults in Vietnam, demonstrates that the media does in fact have a large impact on individuals’ willingness to vaccinate themselves and their children. Nearly three quarters (68.2%) of the subjects interviewed for this study stated that they feel hesitant about vaccines because they have heard about adverse side effects in the media. Vaccine hesitancy rates in our study were much higher than rates described in a previous study in China, which found that after media reports, 30% of parents displayed hesitancy in regard to administering the hepatitis B vaccine to their children.Citation20 We also found that trust and the credibility of the source of information had major roles in driving subjects’ behaviors regarding vaccines after hearing about AEFIs in the media.

In the literature, trust has been highlighted as an important factor for cultivating desire to receive vaccines;Citation35 in other words, insufficient trust leads people to demand more clarification and assurance about the protective benefits of vaccines for their health.Citation36 After national EPI vaccine crises in Vietnam, such as the Quinvaxem incident described in the introduction, it is not surprising that people displayed less trust of government-distributed vaccines and more trust in vaccines made by for-profit companies. Zijtregtop et alCitation37 found that in the Netherlands, the people who displayed less trust of government vaccines were not only more hesitant to accept the vaccines, but also refused vaccination.

In addition, we found that subjects preferring to receive vaccine information from health workers at primary health care levels were more likely to refuse vaccines. These unusual findings may also relate to trust. In Vietnam, people generally perceive the quality of commune-level health workers to be limited,Citation38 which may have led the people in our study to have reduced trust in the information that these health workers provided in regard to vaccines. Yaqub et alCitation36 argued that building trust between health professionals and patients in regard to immunizations might be met with several obstacles such as insufficient time for providers to speak with patients and workers’ lack of knowledge about vaccines. These factors may have made the subjects in our study less likely to believe community health workers who informed them about the safety and benefits regarding vaccines. Therefore, they may choose vaccine refusal rather than hesitancy. More effort should be spent in educating health workers on both the vaccines themselves and how to transmit information about the vaccines effectively to patients and families.

Similarly, our results indicate that people receiving information from friends, relatives or colleagues were more likely to refuse vaccines. The influence of friends, relatives, or colleagues might appear not only during in-person conversations but also via the Internet and social media. Notably, our study emphasized the indispensable role of the media (including Internet, television, radio, etc) as a primary source of vaccination information for our participants, which is consistent with previous studies in Vietnam and other countries.Citation39–Citation41 Some subjects reported to us that they read stories from friends or colleagues about their own experiences with the vaccines on social media sites (eg, Facebook), which might be generalized on larger scale. McMurrayCitation42 pointed out that some people preferred to follow friends’ instructions instead of mainstream evidence from governmental or other authorities, which led some people to develop negative attitudes toward health care.

Several implications can be drawn from this study. First, the quality of vaccination distribution services should be improved at the community level, to enhance subjects’ trust in both the vaccines themselves and the overall EPI program in Vietnam. This might reduce the influence of information from unofficial media sources on individuals’ willingness to receive vaccines. Second, educational campaigns should be created by the government and/or local health workers to sustain people’s awareness of the importance of vaccines to sustain health, as well as their confidence in vaccine production and distribution through the EPI program. These campaigns could be targeted first and foremost to parents, as much of the EPI program focuses on vaccination of children under 6 years old;Citation24 they could include information about the safety of vaccines, the importance of immunization for community health; and the ease with which vaccines can be obtained at local health centers,Citation43 among other information. Finally, collaboration with the news media might be warranted to discuss coverage of AEFIs and vaccines in general. The Vietnamese government could also consider implementing new media strategies such as text message or YouTube campaigns to increase national confidence in the EPI program.Citation44 Doing so might also influence people’s perceptions of other media coverage of AEFIs and their willingness to obtain vaccines for themselves and their children. In general, the influential power of the media can be used in future interventions to encourage vaccinations and support consolidation of both immunizations and information campaigns across Vietnam.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. Because of the cross-sectional design that we employed, we could not establish a causal relationship between media exposure and attitudes toward vaccines. In addition, our convenience sampling method might limit the generalizability of our results to the larger population. However, in health service research, in some cases, good sample frames may not be easy to identify; hence, the selection of clinics purposively and respondents conveniently are accepted and dependent on the health problem to be studied in its specific context. Further studies with larger sample sizes in multiple sites across Vietnam should be conducted in order to confirm our argument in this study in a large scale. Second, our measure was based on a rapid assessment instead of an international measure. This approach could reflect rapidly how large the advert events of vaccination impact consumers’ choices via media. Third, we did not collect data about whether the respondents wanted to have children in the future or not, which might be an important variable for the attitude regarding vaccination. Moreover, perception and reactions of our participants for different specific vaccines were not obtained in this study. Thus, further studies should be elucidated to fill these gaps of knowledge. Finally, more subjects who are parents should also be recruited to examine clearly the impact of the media on the vaccination uptake for Vietnamese children.

Conclusions

These results highlight a significantly high rate of vaccine hesitancy and refusal among subjects living in an urban setting in northern Vietnam, after hearing about AEFIs in the media. These findings reveal the need for development of accurate information systems in the media about immunizations, as well as the development of trust between subjects and health care professionals, as well as the Vietnamese government.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Hanoi Medical University for their administrative support in the implementation of this study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MirelmanAJBallardSBSaitoMKosekMNGilmanRHCost-effectiveness of norovirus vaccination in children in PeruVaccine201533273084309125980428

- ShakerianSMoradi LakehMEsteghamatiAZahraeiMYaghoubiMCost-effectiveness of rotavirus vaccination for under-five children in IranIran J Pediatr2015254e276626396704

- FeikinDRFlanneryBHamelMJStackMHansenPMVaccines for children in low- and middle-income countriesBlackREWalkerNLaxminarayanRTemmermanMReproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health: Disease Control Priorities3rd ed Volume 2Washington, DCThe International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank

- World Health OrganizationImmunization2016 Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/immunization/en/Accessed December 23, 2016

- DohertyMBuchyPStandaertBGiaquintoCPrado-CohrsDVaccine impact: benefits for human healthVaccine201634526707671427773475

- van den HofSSmitCvan SteenbergenJEde MelkerHEHospitalizations during a measles epidemic in the Netherlands, 1999 to 2000Pediatr Infect Dis J200221121146115012488666

- DurbachN“They might as well brand us”: working-class resistance to compulsory vaccination in Victorian EnglandSoc Hist Med2000131456211624425

- YaqubOCastle-ClarkeSSevdalisNChatawayJAttitudes to vaccination: a critical reviewSoc Sci Med201411211124788111

- LarsonHJJarrettCEckersbergerESmithDMPatersonPUnderstanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012Vaccine201432192150215924598724

- JarrettCWilsonRO’LearyMEckersbergerELarsonHJSAGE Working Group on Vaccine HesitancyStrategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy – A systematic reviewVaccine201533344180419025896377

- LarsonHJCooperLZEskolaJKatzSLRatzanSAddressing the vaccine confidence gapLancet2011378979052653521664679

- BeanSJEmerging and continuing trends in vaccine opposition website contentVaccine201129101874188021238571

- CooperLZLarsonHJKatzSLProtecting public trust in immunizationPediatrics2008122114915318595998

- BertrandJTAnhangRThe effectiveness of mass media in changing HIV/AIDS-related behaviour among young people in developing countriesWorld Health Organ Tech Rep Ser2006938205241 Discussion 317–34116921921

- WakefieldMALokenBHornikRCUse of mass media campaigns to change health behaviourLancet201037697481261127120933263

- AbaduraSALereboWTKulkarniUMekonnenZAIndividual and community level determinants of childhood full immunization in Ethiopia: a multilevel analysisBMC Public Health20151597226415507

- JungMLinLViswanathKEffect of media use on mothers’ vaccination of their children in sub-Saharan AfricaVaccine201533222551255725896379

- DubéEVivionMMacdonaldNEVaccine hesitancy, vaccine refusal and the anti-vaccine movement: influence, impact and implicationsExpert Rev Vaccines20151419911725373435

- LiXWiesenEDiorditsaSImpact of adverse events following immunization in Viet Nam in 2013 on chronic hepatitis B infectionVaccine201634686987326055296

- YuWLiuDZhengJLoss of confidence in vaccines following media reports of infant deaths after hepatitis B vaccination in ChinaInt J Epidemiol201645244144927174834

- CapannaAGervasiGCiabattiniMEffect of mass media on influenza vaccine coverage in the season 2014/2015: a regional survey in Lazio, ItalyJ Prev Med Hyg2015562E72E7626789992

- ChenMFWangRHSchneiderJKUsing the Health Belief Model to understand caregiver factors influencing childhood influenza vaccinationsJ Community Health Nurs2011281294021279888

- MorinALemaîtreTFarrandsACarrierNGagneurAMaternal knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding gastroenteritis and rotavirus vaccine before implementing vaccination program: which key messages in light of a new immunization program?Vaccine201230415921592722858556

- MoHNational Expanded Program on Immunization – Comprehensive Multi-Year Plan – cMYP for Extended Program on Immunization 2016–2020Hanoi, Vietnam2015

- NguyenTDDangADvan DammePCoverage of the expanded program on immunization in Vietnam: Results from 2 cluster surveys and routine reportsHum Vaccin Immunother20151161526153325970593

- JitMDangTTFribergIThirty years of vaccination in Vietnam: impact and cost-effectiveness of the national Expanded Programme on ImmunizationVaccine201533Suppl 1A233A23925919167

- Organization WH, UNICEFWHO-UNICEF estimates of DTP3 coverage2017 Available from: http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/timeseries/tswucoveragedtp3.htmlAccessed November 11, 2017

- World Health OrganizationAdverse events following immunization (AEFI)2017 Available from: http://www.who.int/vaccine_safety/initiative/detection/AEFI/en/Accessed November 29, 2017

- ImmunizationVNEPoAnnual EPI ReportHanoi, Vietnam2008

- World Health OrganizationSafety of Quinvaxem (DTwP-HepB-Hib) pentavalent vaccine2017 Available from: http://www.who.int/immu-nization_standards/vaccine_quality/quinvaxem_pqnote_may2013/en/Accessed November 29, 2017

- World Health OrganizationSafety of Quinvaxem (DTwP-HepB-Hib) pentavalent vaccine2013 Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization_standards/vaccine_quality/quinvaxem_pqnote_may2013/en/Accessed January 7, 2018

- CapedingMRCadorna-CarlosJBook-MontellanoMOrtizEImmunogenicity and safety of a DTaP-IPV//PRP approximately T combination vaccine given with hepatitis B vaccine: a randomized open-label trialBull World Health Organ200886644345118568273

- LwangaSKLemeshowSSample Size Determination in Health Studies, A Practical ManualGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization1991

- MidiHSarkarSKRanaSCollinearity diagnostics of binary logistic regression modelJ Interdisc Math2010133253267

- RoalkvamSMcNeillDBlumeSProtecting the World’s Children – Immunisation Policies and PracticesOxfordOxford University Press2013

- YaqubOCastle-ClarkeSSevdalisNChatawayJAttitudes to vaccination: a critical reviewSoc Sci Med2014112Supplement C11124788111

- ZijtregtopEAWilschutJKoelmaNWhich factors are important in adults’ uptake of a (pre)pandemic influenza vaccine?Vaccine200928120722719800997

- World BankQuality and Equity in Basic Health Care Services in Vietnam: Findings from the 2015 Vietnam District and Commune Health Facility SurveyWashington, DCWorld Bank2016

- WebbTLJosephJYardleyLMichieSUsing the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacyJ Med Internet Res2010121e420164043

- AmanteDJHoganTPPagotoSLEnglishTMLapaneKLAccess to care and use of the Internet to search for health information: results from the US National Health Interview SurveyJ Med Internet Res2015174e10625925943

- DinhTARosenthalSLDoanEDAttitudes of mothers in Da Nang, Vietnam toward a human papillomavirus vaccineJ Adolesc Health200740655956317531763

- McMurrayRCheaterFMWeighallANelsonCSchweigerMMukherjeeSManaging controversy through consultation: a qualitative study of communication and trust around MMR vaccination decisionsBr J Gen Pract20045450452052515239914

- SalmonDAMoultonLHOmerSBDehartMPStokleySHalseyNAFactors associated with refusal of childhood vaccines among parents of school-aged children: a case-control studyArch Pediatr Adolesc Med2005159547047615867122

- OdoneAFerrariASpagnoliFEffectiveness of interventions that apply new media to improve vaccine uptake and vaccine coverageHum Vaccin Immunother2015111728225483518