Abstract

Purpose

Ulcerative colitis (UC) may cause many patients to miss out on important personal and professional opportunities. We therefore conducted a survey (UC-LIFE) to assess patients’ perceptions of the impact of UC on social and professional lives.

Patients and methods

Consecutive unselected UC patients aged ≥18 years were recruited from 38 outpatient clinics in Spain. Patients completed the survey at home, returning it by post. The survey comprised 44 multiple-choice questions, including questions about the impact of UC on social, personal, professional, and academic activities.

Results

Of 585 patients invited, 436 (75%) returned the survey (mean age 46 years; 47% women). High proportions of patients considered their disease “sometimes”, “frequently” or “mostly/always” influenced leisure activities (65.1%), recreational or professional activities (57.6%), or relationships with relatives or friends (9.9%). Patients also reported that UC influenced their decision to have children (17.2%), or their ability to take care of children (40.7%); these percentages were higher in women and in younger patients. Overall, 47.0% of patients declared that UC influenced the kind of job they performed, 20.3% had rejected a job due to UC, 14.7% had lost a job due to UC, and 19.4% had had academic problems due to UC.

Conclusion

Beyond symptoms alone, UC imposes an enormous additional burden on patients’ social, professional, and family lives. This extra burden clearly needs to be addressed so that the ultimate goal of IBD treatment – normalization of patient quality of life – can be attained by as many patients as possible.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic and idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) affecting the mucosal layer of the colon. The degree of mucosal involvement varies from proctitis (only the rectum is affected) to pancolitis (the entire colon is affected). UC is typically diagnosed in early adulthood and clinically characterized by relapsing and remitting symptoms such as diarrhea, rectal bleeding, abdominal pain, fecal urgency, weight loss, and fatigue; in up to one third of patients, these symptoms are accompanied by articular, dermatological, and/or ocular diseases.Citation1,Citation2 Although most UC patients present with a mild-to-moderate disease course, about 14%–17% of patients may experience an aggressive course.Citation3 These patients may require hospital admission, and up to 19% of patients with pancolitis will need colectomy, typically during the first 2 years after diagnosis.Citation4 Thus, although UC does not reduce life expectancy, it is a markedly disabling disease for a considerable number of patients.Citation5

UC presents two peaks of incidence: the main one at age 30–40 years, and another one at about 60 years.Citation1 Younger patients seem to present with a worse disease course than patients with disease onset after age 60 years.Citation6 As UC frequently begins during a stage of life when people develop a professional career and start a family, and together with its hallmark symptoms, chronicity, and relapsing nature, the condition has a substantial impact on patients’ lives, in many cases, important personal and professional opportunities may be lost for patients.Citation7–Citation13

Globally, the incidence and prevalence of UC have been increasing over time, as have costs associated with the disease.Citation14 In Europe, the annual direct and indirect costs related to UC are estimated to be as high as €12.5–29.1 billion. More than half of this figure is attributable to the indirect cost of absence from paid work, which includes costs associated with sick leave, early retirement, and reduced employment.Citation15

Because the burden of UC surpasses clinical symptoms alone, we considered it interesting to collect information directly from patients through a cross-sectional survey (UC-LIFE) about their perception of how UC affects various aspects of their everyday lives. The survey characteristics and several outcomes have been published previously.Citation16–Citation18 Herein, we present insights from the UC-LIFE survey about the impact of UC on the social and professional lives of Spanish patients followed in outpatient clinics.

Patients and methods

Ethics approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the Clinical Investigation Ethics Committee of the Parc Taulí Hospital, Barcelona, Spain. The survey documentation included printed instructions and information for patients about the anonymous nature of the survey and aggregated data processing which ensured that patient identification was not possible. Given that no identifiable information was collected, and as accepted by the Clinical Investigation Ethics Committee, no signed informed consent was requested, the voluntary return of completed questionnaires was taken as implied consent to participate in the study.

A detailed description of the UC-LIFE survey, subjects, and procedures has been published previously.Citation16–Citation18 A brief summary of study methodology, participants, and procedures is provided in the following section.

Unselected patients aged ≥18 years with UC who were attending one of 38 representative hospital gastroenterology clinics throughout Spain were recruited consecutively for the study and handed the survey.

At-home completion of the survey was voluntary and anonymous, with no collection of clinical data; invited patients received no reminders to complete the survey.

The UC-LIFE survey consisted of 44 multiple-choice questions regarding details about patient demographics; perceptions about the burden associated with UC symptoms and severity; the emotional burden of the disease in terms of daily life and other aspects described previously.Citation16–Citation18 Specifically, the survey included questions about the impact of UC on social, personal, professional, and academic activities of patients, and about the influence of UC on childcare. These questions were formulated with wording based on physician and patient recommendations. Several questions included a Likert scale ranging from “never” to “mostly/always”, while others were answered as “yes” or “no”. The full questionnaire is available as supplemental content to the main publication: http://links.lww.com/EJGH/A110.Citation16

Due to the exploratory and descriptive nature of the survey, there was no formal statistical hypothesis or pre-determined sample size. Mean and SDs were used to describe quantitative variables or, if data were not distributed normally, median and interquartile range (IQR) were used. Frequencies or percentages were used for nominal or ordinal variables. Proportional data (eg, gender, age, disease duration, burden of symptoms during the previous year) were compared using the Chi-squared or Fisher exact tests. Multiple subgroup comparisons were performed using the least significant differences test. Statistical significance was considered for P-values ≤0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 18.0.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Demographic data

Thirty-nine physicians handed out the survey to 585 UC patients, and 436 patients returned the questionnaire (response rate 74.5%). Due to the anonymous nature of the survey, the profile of non-responding patients is unknown. Responders had a mean age of 46.2 (SD 13.6) years, 52.8% were men, and the median duration of UC was 8 years (IQR 4–15). Sixty-nine percent of patients were married or had a partner, and 52.7% were active workers. When asked about perceived symptom burden during the previous year, 47.1% of patients reported “symptoms controlled”, and 28.0% and 24.9%, respectively, reported “symptoms not impairing everyday life” or “symptoms impairing everyday life”.

Impact of UC on social and family life

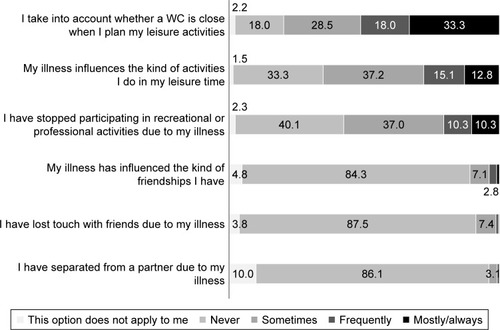

depicts the responses of patients to statements about how they perceived the impact of UC on their social lives. A high proportion of patients considered their disease “sometimes”, “frequently” or “mostly/always” influenced leisure activities (65.1% of patients), recreational or professional activities (57.6%), or relationships with relatives or friends (9.9%). For several statements related to leisure activities, the percentage of patients who responded “frequently” or “mostly/always” was significantly higher in patients who perceived more severe UC-related symptoms (). Nonetheless, substantial proportions of patients who described their UC-related symptoms as “controlled” or “present but not impairing everyday life” still responded “frequently” or “mostly/always” to questions about leisure activities: for example, 32.0% of patients with symptoms “controlled” and 52.3% of those with symptoms “present but not impairing everyday life” responded “frequently” or “mostly/always” to the statement “I take into account whether a WC is close when I plan my leisure activities”. The frequencies of responses were similar by tertiles of age and disease duration (data not shown), but frequencies of a “frequently” or “mostly/always” response to several statements were slightly higher in women than in men ().

Figure 1 Patients’ responses to statements about the impact of ulcerative colitis on their social lives.

Abbreviation: WC, water closet.

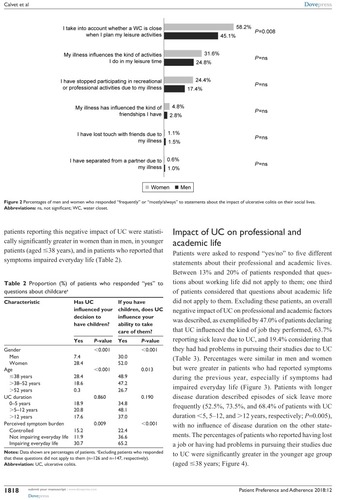

Figure 2 Percentages of men and women who responded “frequently” or “mostly/always” to statements about the impact of ulcerative colitis on their social lives.

Table 1 ProportionTable Footnotea of patients who responded “frequently” or “mostly/always” to questions about their social lives

Patients were asked about the impact of UC on their decision to have children and their ability to take care of children (). Excluding patients who responded that these questions did not apply to them (n=126 and n=147, respectively), 48 of 278 patients (17.2% overall: 7.4% of men; 28.4% of women) reported that UC had influenced their decision to have children, and 104 of 255 patients (40.7% overall: 30.0% of men; 52.0% of women) agreed that UC influenced their ability to take care of children. The percentages of patients reporting this negative impact of UC were statistically significantly greater in women than in men, in younger patients (aged ≤38 years), and in patients who reported that symptoms impaired everyday life ().

Table 2 Proportion (%) of patients who responded “yes” to questions about childcareTable Footnotea

Impact of UC on professional and academic life

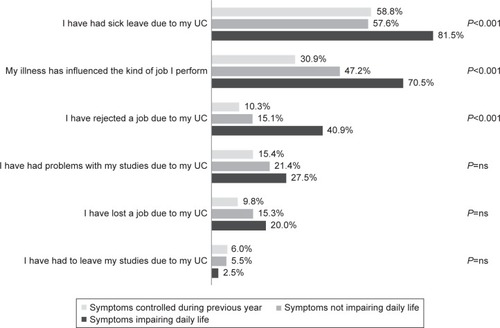

Patients were asked to respond “yes/no” to five different statements about their professional and academic lives. Between 13% and 20% of patients responded that questions about working life did not apply to them; one third of patients considered that questions about academic life did not apply to them. Excluding these patients, an overall negative impact of UC on professional and academic factors was described, as exemplified by 47.0% of patients declaring that UC influenced the kind of job they performed, 63.7% reporting sick leave due to UC, and 19.4% considering that they had had problems in pursuing their studies due to UC (). Percentages were similar in men and women but were greater in patients who had reported symptoms during the previous year, especially if symptoms had impaired everyday life (). Patients with longer disease duration described episodes of sick leave more frequently (52.5%, 73.5%, and 68.4% of patients with UC duration <5, 5–12, and >12 years, respectively; P=0.005), with no influence of disease duration on the other statements. The percentages of patients who reported having lost a job or having had problems in pursuing their studies due to UC were significantly greater in the younger age group (aged ≤38 years; ).

Figure 3 Percentages of patients who responded “yes” to statements about the impact of ulcerative colitis on professional and academic life (stratified by perception of symptomatic burden).

Figure 4 Percentages of patients who responded “yes” to statements about the impact of ulcerative colitis on professional and academic life (stratified by age [tertiles]).

![Figure 4 Percentages of patients who responded “yes” to statements about the impact of ulcerative colitis on professional and academic life (stratified by age [tertiles]).](/cms/asset/fbd7c908-d706-42cf-afd3-ada100068110/dppa_a_175026_f0004_b.jpg)

Table 3 ProportionTable Footnotea of patients who responded “yes” to questions about professional or academic factorsTable Footnoteb

Discussion

The principal findings of this large, cross-sectional survey are the significant, patient-perceived burdens of UC on social and family life, and on professional and academic life. These findings are of considerable relevance for several reasons: first, these kinds of findings are not frequently reported from large populations, and even less frequently directly from patients, with no physician intervention or interpretation. Second, we provided a comprehensive description of the social and professional impact of the disease and described a link to disease activity as perceived by the patient. Finally, these specific impacts are evident even in patients who reported that their symptoms were “controlled”, which is something that merits special attention. High proportions of patients reported that UC markedly influenced leisure activities and relationships with relatives or friends. This applied even in patients who reported that symptoms were “controlled” or “not impairing daily life”. Substantial proportions of patients also reported that UC had influenced their decision to have children, or their ability to look after children. These proportions were significantly greater in younger patients, and patients with a high perceived symptom burden. Regarding professional and academic life, almost half of patients reported that UC influenced the job they performed, almost two thirds documented sick leave due to UC, and almost one fifth reported difficulties in pursuing their studies because of UC. A significantly greater proportion of younger patients compared to older patients had lost a job because of UC or had experienced study problems due to UC.

Particular strengths of the current survey are its ability to glean real-world evidence from the patient perspective and obtain broader knowledge of the overall impact of UC on patient quality of life (QoL). This is particularly pertinent given the ever-increasing focus on patient-reported outcomes in IBD,Citation16,Citation19 and the increasing recognition of often divergent goals of physicians and IBD patients. In fact, it has been described previously that the most desirable goals for patients are often symptom control and normalization of QoL,Citation16,Citation19 goals that must be attained together with the histological goal of complete mucosal healing. Indeed, the continuous control of symptoms in UC patients has been associated with long-term steroid-free remission, endoscopic remission, and mucosal healing,Citation20 but minimizing the impact of UC on patients’ social and professional life must also be taken into account as a patient goal. Attaining both physicians’ and patients’ goals might therefore be the optimal objective in achieving complete UC clinical control.

We have previously described that the prevalence of specific UC symptoms was substantial even among patients who had defined their symptoms as “controlled”,Citation16 suggesting that patients could accept some degree of living with troublesome symptoms as “normal”. In the current work, we extended this finding to several effects of UC on social and professional life: patients who considered their symptoms to be “controlled” also described frequent limitations with regard to social and professional life. In failing to realize the full therapeutic potential of treatment, many patients may fail to attain the maximum possible QoL improvements. Even in the presence of endoscopic and symptomatic cure, many IBD patients do not attain normalization of QoL.Citation21,Citation22 These patients may be more likely to experience problems with fatigue, anxiety, depression, deteriorating treatment adherence, and increased work disability.Citation8,Citation21,Citation23 A direct consequence will likely be an increased overall use of health care resources.Citation21

Our survey, in highlighting the major scale of disease burden posed by UC, endorses other study findings. Regarding family life, for instance, the extent of misperception about IBD and fertility is broadly recognized. A Mediterranean-region study reported that more than 60% of women with IBD were fearful that their disease and treatment might lead to a complicated pregnancy and fetal damage.Citation11 An Australian study also outlined that, after a diagnosis of IBD, three quarters of women were worried about passing the disease to their offspring, about half were worried about infertility, and approximately one third considered not having children.Citation12 Other researchers corroborated that “voluntary” childlessness in IBD patients may result from apparently unjustified concerns about detrimental reproductive outcomes.Citation13

Regarding the impact of IBD on social life and leisure activities, our survey found that, even in patients with symptoms reported as “controlled” or “not impairing daily life”, the disease had a marked negative influence on several aspects of social life: 32% and 52% of those patients, respectively, reported the need for a nearby WC when planning leisure activities; 13% and 23%, respectively, expressed that IBD influenced the type of activity undertaken; and 8% and 16%, respectively, indicated that they had stopped participating in recreational or professional activities because of IBD. These findings are in line with data from the initial UC-LIFE publication,Citation16 which revealed that patients who considered their symptoms “controlled/nearly controlled” still experienced a marked prevalence of some symptoms: diarrhea, urgency, rectal bleeding, flatulence, fatigue, abdominal pain, and joint pain. Moreover, the UC-LIFE survey showed that high symptom burden during the previous year (ie, “symptoms impairing everyday life”) had a significant influence on all evaluated aspects of patients’ social, personal, and professional lives. This clearly underscores the suggestion that attainment of symptom control in UC patients is an essential first step toward true normalization of QoL.

Our survey findings of a markedly deleterious effect of IBD on various aspects of professional and academic life are clearly in agreement with data from large surveys,Citation24 systematic reviews,Citation10 and other trials.Citation8,Citation9,Citation25 For example, in a large European survey in >4,500 IBD patients, most patients reported that their disease had caused absence from work, and 45% commented that IBD had a negative impact on educational performance.Citation24 Moreover, in a study of IBD patients at a Dutch outpatient clinic, de Boer et al documented that 25% of employed patients were on sick leave, about one quarter were receiving a disability pension, and approximately three quarters had work-related difficulties such as concentration problems and slow work pace.Citation8 A lack of paid employment was associated with worse QoL and greater rates of anxiety and depression.Citation8

Another interesting finding in our survey was the major impact of age on work and academic performance: notably, among patients aged ≤38 years, 18% reported that UC had caused them to lose their job, and 24% reported that UC had caused study problems. Speculation suggests that such high rates of work loss and study impairment in young patients may be linked with increased rates of psychological and psychiatric morbidity (eg, anxiety, depression).Citation26,Citation27

While it is difficult to accurately quantify the holistic burden of UC on social and professional life, the UC-LIFE survey is a significant step in this direction, and its findings highlight the need to tackle the consequences of UC not only from medical, but also from social perspectives. However, the study has some limitations:Citation16 data were derived from patient self-assessment of symptoms during the previous year and may therefore have been confounded by recall bias; and some degree of selection bias was present, since the survey was distributed through hospital outpatient clinics, and the population did not truly reflect the overall UC population. Thus, study findings from these selected patient groups in Spain are not necessarily applicable to other geographical areas and to broader populations of UC patients. Nevertheless, only when efforts have been made to quantify the full impact of UC on QoL, including on aspects beyond straightforward symptom control (ie, on aspects of social, professional, and family lives), can attempts be made to fully normalize QoL in UC patients. Future studies, using objective, well-validated measures, are now warranted to more clearly define the impact of UC on QoL, and the effects of treatment and improved adherence to treatment in normalizing QoL in UC patients.

Conclusion

The insights from patients presented here underscore how UC can influence many aspects of patients’ everyday lives, including social and family activities and relationships, and freedom to enjoy leisure time and participate in professional and academic activities; UC can also have a major bearing on potentially life-changing decisions for patients, such as which type of employment to pursue, or whether or not to have children. These aspects are seldom considered or addressed in studies and are difficult to quantify, but impose an enormous extra burden on patients, well beyond UC symptoms alone. Such aspects of patients’ social, professional, and family lives clearly need to be addressed, in line with patient-centered approaches to UC management, so that the ultimate goal of IBD treatment – normalization of patient QoL – can be attained by as many patients as possible.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Alejandro Pedromingo (Bioestadística, Madrid, Spain). Medical writing assistance was provided by David Murdoch and David P Figgitt PhD, ISMPP CMPP™, Content Ed Net, and funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Spain.

The authors wish to thank the patients for their contribution in filling out printed surveys, and the following gastroenterologists (in alphabetical order) for contributing to the work by distributing surveys to patients: Dr María M Alcalde, Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina, Badajoz; Dr Xavier Aldeguer, Hospital Universitario Doctor Josep Trueta, Gerona; Dr Federico Argüelles-Arias, Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, Sevilla; Dr Maite Arroyo, Hospital Universitario Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza; Dr Nelly Balza, Hospital Son Llàtzer, Mallorca; Dr Jesús Barrio, Hospital Universitario Río Hortega, Valladolid; Mrs Olga Benítez, Hospital Universitario Mútua de Terrassa, Barcelona; Dr Fernando Bermejo, Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada, Madrid; Dr José L Cabriada, Hospital de Galdakao,Vizcaya; Dr Xavier Calvet, Corporación Sanitaria Universitaria Parc Taulí, Barcelona; Dr Raquel Camargo, Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria, Málaga; Dr Daniel Carpio, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Pontevedra, Pontevedra; Dr María L Castro, Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, Sevilla; Dr Daniel Ceballos, Hospital Universitario Doctor Negrín, Gran Canaria; Dr Cristobal de la Coba, Hospital de Cabueñes, Asturias; Dr Xavier Cortés, Hospital de Sagunto, Valencia; Dr Eugeni Domènech, Hospital Universitario Germans Trias i Pujol, Barcelona; Dr Carmen Dueñas, Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara, Cáceres; Dr María Fe García, Hospital Universitario de Elche, Alicante; Dr Santiago García, Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza; Dr Valle García, Hospital Universitario Reina Sofia, Córdoba; Dr Rosario Gómez, Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves, Granada; Dr Pedro González, Complejo Hospitalario La Mancha Centro, Ciudad Real; Dr Jordi Guardiola, Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, Barcelona; Dr Álvaro Hernández, Hospital de Torrecárdenas, Almería; Dr Esteban Hernández, Hospital Universitario del Henares, Madrid; Dr José M Huguet, Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia, Valencia; Dr Antonio López-Sanromán, Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Madrid; Dr Pilar Martínez, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid; Dr Teresa Martínez, Hospital Rafael Méndez, Murcia; Dr Ana Muñagorri, Hospital Universitario de Donostia, San Sebastián; Dr Concepción Muñoz, Hospital Virgen de la Salud, Toledo; Dr José F Muñoz, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca; Dr Héctor Pallarés, Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez, Huelva; Dr Laura Ramos, Hospital Universitario La Laguna, Tenerife; Dr Montserrat Rivero, Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla; Cantabria; Dr Antonio Rodríguez, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca; Dr Cristina Rodríguez, Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra, Navarra; Dr Patricia Romero, Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucia, Murcia.

This project was financed by Merck Sharp & Dohme Spain, a subsidiary of Merck & Co, Whitehouse Station, New Jersey, USA, and is endorsed by the Spanish Association of Patients with Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis.

Disclosure

X Calvet has served as speaker, consultant and advisor, or has received funding for research, from Merck Sharp & Dohme, AbbVie, Hospira, Pfizer, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, and Vifor Pharma. F Argüelles-Arias has served as speaker, consultant and advisor, or has received funding for research, from Merck Sharp & Dohme, AbbVie, Takeda, Tillotts, Kern-Pharma, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Gebro Pharma, and Vifor Pharma. A López-Sanromán has served as speaker, consultant or advisor for Merck Sharp & Dohme, AbbVie, Hospira, Gebro Pharma, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, and Tillotts. L Cea-Calvo, B Juliá, and C Romero de Santos are full-time employees in the Medical Affairs Department, Merck Sharp & Dohme Spain. D Carpio has served as consultant to Merck Sharp & Dohme, AbbVie, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma, has received payment as speaker from Merck Sharp & Dohme, AbbVie, Pfizer, Takeda, Shire, Gebro Pharma, Tillotts, Dr Falk Pharma, and Almirall, and has been involved in clinical research with Merck Sharp & Dohme, AbbVie, and Tygenix. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- UngaroRMehandruSAllenPBPeyrin-BirouletLColombelJFUlcerative colitisLancet2017389100801756177027914657

- Marín-JiménezIGarcía SánchezVGisbertJPImmune-mediated inflammatory diseases in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Baseline data from the Aquiles studyGastroenterol Hepatol201437949550224717523

- FumeryMSinghSDulaiPSGower-RousseauCPeyrin-BirouletLSandbornWJNatural history of adult ulcerative colitis in population-based cohorts: A systematic reviewClin Gastroenterol Hepatol201816334335628625817

- MagroFRodriguesAVieiraAIReview of the disease course among adult ulcerative colitis population-based longitudinal cohortsInflamm Bowel Dis201218357358321793126

- Peyrin-BirouletLCiezaASandbornWJDevelopment of the first disability index for inflammatory bowel disease based on the international classification of functioning, disability and healthGut201261224124721646246

- CharpentierCSalleronJSavoyeGNatural history of elderly-onset inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort studyGut201463342343223408350

- MarriSRBuchmanALThe education and employment status of patients with inflammatory bowel diseasesInflamm Bowel Dis200511217117715677911

- de BoerAGBennebroek Evertsz’FStokkersPCEmployment status, difficulties at work and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease patientsEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol201628101130113627340897

- Vester-AndersenMKProsbergMVVindIAnderssonMJessTBendtsenFLow risk of unemployment, sick leave, and work disability among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A 7-year follow-up study of a Danish inception cohortInflamm Bowel Dis201521102296230326164663

- BüschKda SilvaSAHoltonMRabacowFMKhaliliHLudvigssonJFSick leave and disability pension in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic reviewJ Crohns Colitis20148111362137725001582

- EllulPZammitaSCKatsanosKHPerception of reproductive health in women with inflammatory bowel diseaseJ Crohns Colitis201610888689126783343

- SelingerCPEadenJSelbyWInflammatory bowel disease and pregnancy: lack of knowledge is associated with negative viewsJ Crohns Colitis201376e206e21323040449

- MountifieldRBamptonPProsserRMullerKAndrewsJMFear and fertility in inflammatory bowel disease: a mismatch of perception and reality affects family planning decisionsInflamm Bowel Dis200915572072519067431

- MolodeckyNASoonISRabiDMIncreasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic reviewGastroenterology20121421465422001864

- CohenRDYuAPWuEQXieJMulaniPMChaoJSystematic review: the costs of ulcerative colitis in Western countriesAliment Pharmacol Ther201031769370720064142

- CarpioDLópez-SanrománACalvetXPerception of disease burden and treatment satisfaction in patients with ulcerative colitis from outpatient clinics in Spain: UC-LIFE surveyEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol20162891056106427286569

- López-SanrománACarpioDCalvetXPerceived emotional and psychological impact of ulcerative colitis on outpatients in Spain: UC-LIFE surveyDig Dis Sci201762120721627817123

- Argüelles-AriasFCarpioDCalvetXKnowledge of disease and access to a specialist reported by Spanish patients with ulcerative colitis. UC-LIFE surveyRev Esp Enferm Dig2017109642142928605920

- CasellasFHerrera-de GuiseCRoblesVNavarroEBorruelNPatient preferences for inflammatory bowel disease treatment objectivesDig Liver Dis201749215215627717791

- ReinischWColombelJFGibsonPRContinuous clinical response is associated with a change of disease course in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis treated with golimumabInflamm Bowel Dis Epub201876

- CasellasFBarreiro de AcostaMIglesiasMMucosal healing restores normal health and quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol201224776276922517240

- CasellasFRoblesVBorruelNRestoration of quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease after one year with antiTNFα treatmentJ Crohns Colitis20126988188622398074

- Romberg-CampsMJBolYDagneliePCFatigue and health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a population-based study in the Netherlands: the IBD-South Limburg cohortInflamm Bowel Dis201016122137214720848468

- LönnforsSVermeireSGrecoMHommesDBellCAvedanoLIBD and health-related quality of life – discovering the true impactJ Crohns Colitis20148101281128624662394

- KimYSJungSALeeKMImpact of inflammatory bowel disease on daily life: an online survey by the Korean Association for the Study of Intestinal DiseasesIntest Res201715333834428670230

- Mckee-RyanFSongZWanbergCRKinickiAJPsychological and physical well-being during unemployment: a meta-analytic studyJ Appl Psychol2005901537615641890

- BurnsJMAndrewsGSzaboMDepression in young people: what causes it and can we prevent it?Med J Aust2002177SupplS93S9612358564