Abstract

Background

Many patients at high cardiovascular risk do not reach targets for low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and blood pressure (BP). Depression is a frequent comorbidity in these patients and contributes to poor medication adherence.

Objective

The aim of this study was to elucidate the associations between adherence to lipid-and BP-lowering drugs, the diagnosis of depression, and the control of LDL-C and BP.

Patients and methods

This study was conducted as multicenter, single-visit cross-sectional study in Germany. Adherence was assessed by the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8 (MMAS-8), and depression was assessed as documented in the patient chart.

Results

A total of 3,188 ambulatory patients with hypercholesterolemia (39.8%), stable coronary artery disease (CAD; 7.4%), or both (52.9%) were included. Patients had a history of myocardial infarction (30.8%), diabetes (42.0%), were smokers (19.7%), and 16.1% had the investigator-reported diagnosis of depression. High or moderate adherence to lipid-lowering medication compared to low adherence was associated with lower LDL-C levels (105.5±38.3 vs 120.8±42.4 mg/dL) and lower BP (systolic BP 133.4±14.5 vs 137.9±13.9 mmHg, diastolic BP 78.3±9.6 vs 81.8±9.6 mmHg) and with a higher proportion of patients achieving the guideline-recommended LDL-C (16.9% vs 10.1%) and BP target (52.2% vs 40.8%, all comparisons P<0.0001). Adherence was worse in patients with depression. Correspondingly, patients with depression showed higher LDL-C levels, higher BP, and a lower probability of achieving the LDL-C and BP goal. Medication adherence correlated between BP- and lipid-lowering medications.

Conclusion

Self-reported medication adherence can be easily obtained in daily practice. A low adherence and the diagnosis of depression identify patients at risk for uncontrolled LDL-C and BP who likely benefit from intensified care.

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) such as coronary artery disease (CAD) are the leading cause of death worldwide.Citation1 Large randomized controlled trials have shown that lowering of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and blood pressure (BP) is beneficial in primary and secondary prevention of CVD.Citation2,Citation3

The current European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) guidelines recommend achieving LDL-C levels of <70 and <100 mg/dL for patients at very high and high risk, respectively.Citation4 However, despite the availability of effective and well-tolerated drugs, the LDL-C of the majority of patients remains uncontrolled.Citation5–Citation7 There are several factors influencing the risk factor control including adherence to medication defined as “the extent to which patients take medications as prescribed by their health care providers”.Citation8 Adherence to lipid- and BP-lowering medication gets worse over time. A few months after initiation, a very significant part of the patients stops taking the prescribed medication.Citation9–Citation11 Poor statin adherence has been linked to cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.Citation12–Citation14 Adherence to statins is associated with improved LDL-C levels.Citation15 Similarly, improving adherence to BP medication has been shown to improve BP control and clinical outcomes.Citation16,Citation17 However, it is not well studied whether the data regarding adherence to BP-lowering medication can be extrapolated to adherence to lipid-lowering medication. In general, poor adherence to cardiovascular medication causes a considerable proportion of cardiovascular events and deaths.Citation18,Citation19

Up to 20% of patients with CVD suffer from major depression.Citation20 A bidirectional relationship has been assumed between these two disease entities.Citation21 Depression is likely to contribute to non-adherence to lipid- and BP-lowering drugs, which may represent a link between depressive symptoms and risk of CVD.Citation22

Therefore, the aim of this study was to elucidate the association between adherence to lipid- and BP-lowering drugs and the diagnosis of depression.

Patients and methods

This multicenter, single-visit cross-sectional study was conducted in Germany between March 15, 2017, and September 15, 2017. General practitioners and specialists treating outpatients were encouraged to include 10 consecutive patients scheduled for routine appointment. Inclusion criteria were as follows:

≥18 years of age

Hypertension as documented diagnosis

Hypercholesterolemia or stable CAD as documented diagnosis

Current medication with at least one antihypertensive drug

Current medication with a statin

Signed informed consent.

Patients who had been hospitalized because of a cardiovascular event within the past 3 months were excluded.

After the patients had signed the informed consent, the participating physicians collected the following data:

Age and sex

Cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities

Depression (yes/no)

Current antihypertensive medication

Current statin medication

Systolic and diastolic BP (SBP, DBP) values, measured at the documentation visit according to the ESC/European Society of Hypertension (ESH) guidelineCitation23

Control of hypertension according to physician

Serum lipid levels (total cholesterol, LDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C], triglycerides), if measured within the past 12 months

Control of LDL-C according to physician

Eligibility of the patient for taking a fixed-dose combination (FDC) according to the physician and the reason for prescribing FDC pills.

Adherence to antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medication was determined using the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8 (MMAS-8), a self-report questionnaire comprising eight items.Citation24 MMAS-8 values of <6 were classified as “low adherence”, 6 or 7 as “moderate adherence”, and 8 as “high adherence”. Results regarding adherence are based on the MMAS-8 scores for adherence to lipid-lowering medication. LDL-C goals were defined according to the current ESC/EAS guideline as <70 mg/dL in patients with CAD or at very high cardiovascular risk and <100 mg/dL in patients at high cardiovascular risk.Citation4

The study protocol was in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee (Ärztekammer des Saarlandes 307/16).

Statistical analyses

Categorical values are expressed as the percentage of the evaluable patients for each variable, excluding patients with missing data. Continuous data are expressed as mean ± SD. Categorical data were compared using the chi-squared test; for continuous data, the two-sample t-test was used. For comparison of BP and LDL-C control according to ESC guideline vs investigator, the McNemar test was utilized. Logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with adherence, LDL-C control, and BP control. The following factors were included in the regression analyses: age (defined as males older than 55 years and females older than 65 years), sex, smoking, depression, history of myocardial infarction, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, stroke or transient ischemic attack, chronic heart failure, renal disease, positive family history of CAD, positive family history of hypercholesterolemia, adherence to, respectively, lipid- and BP-lowering medication, single-pill combination treatment for hypertension, and single-pill combination treatment for hypercholesterolemia. The analyses were performed with SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 1,247 physicians participated, who included 3,312 patients (76.5% included by general practitioners, 23.5% by specialists), of whom 3,188 were available for final analysis.

Demographic characteristics and risk factors

The baseline characteristics are summarized in . Of the 3,188 patients, 60.9% were male, 61.4% were aged between 60 and 79 years. 39.8% of the patients had a diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia, 7.4% had a diagnosis of stable CAD, and 52.9% had both diagnoses. 30.8% of the patients had a history of myocardial infarction. The most present cardiovascular risk factors were age (76.3%, defined as males older than 55 years or females older than 65 years), diabetes (42.0%), and positive family history of CAD (28.8%); 19.7% of the patients were smoking.

Table 1 Demographic parameters, comorbidities, and medication adherence for the total population, for patients with vs without depression, and for patients with low vs moderate or high adherence

Patients with depression

Depression was diagnosed in 16.1% of the patients (n=512). The majority of patients with depression were female (57.4%), corresponding to 23.9% of the female patients and 11.4% of the male patients were with depression (P<0.0001). Among the patients with depression, a higher proportion had a history of previous stroke or transient ischemic attack (16.8% vs 10.6%), a positive family history of hypercholesterolemia (32.2% vs 23.6%), chronic heart failure (26.4% vs 17.6%), renal disease (20.5% vs 13.8%), and familial hypercholesterolemia (34.0% vs 24.0%, for all comparisons P<0.0001). Patients with depression were more often smokers (24.4% vs 18.8%, P=0.0032) and were prescribed more pills per day (7.2±3.3 vs 6.2±3.2, P<0.0001). Adherence to lipid-lowering medication was worse in patients with depression (). In logistic regression analyses, depression was associated with poor BP control (P=0.0211), poor LDL-C control (P=0.0452), and poor medication adherence (P<0.0001).

Patients with low vs moderate or high adherence to lipid-lowering medication

42.0% of the patients exhibited low, 28.1% moderate, and 29.9% high self-reported adherence to their lipid-lowering medication. There were no significant differences between patients with high vs moderate adherence in LDL-C levels as well as LDL-C and BP control. Therefore, patients with high and moderate adherence were analyzed as one group and compared to patients with low adherence ().

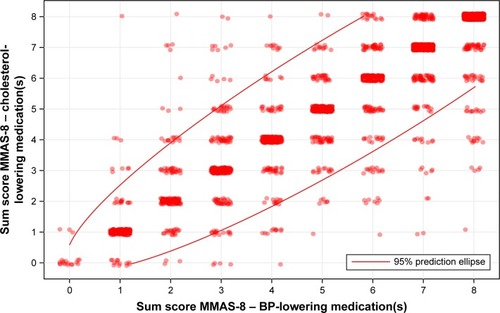

Figure 1 BP (A) and LDL-C control (B) in different subgroups.

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MMAS-8, Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8.

In comparison to patients with moderate or high adherence, patients with low adherence were younger; a higher proportion had a family history of CAD (33.2% vs 25.0%) and hypercholesterolemia (29.5% vs 21.7%) and a history of depression (20.0% vs 13.4%, for all comparisons P<0.0001), peripheral vascular disease (13.3% vs 10.1%, P=0.0074), and familial hypercholesterolemia (28.9% vs 22.6%, P<0.0001). Patients with low adherence were significantly more often smokers (27.1% vs 14.7%, P<0.0001). The number of daily doses was comparable in both groups (6.3±3.0 vs 6.5±3.3, P=0.2101). There was no correlation between the number of daily doses and adherence measured by MMAS-8 (Spear-man’s correlation coefficient -0.00434, P=0.8118). The data are summarized in .

High adherence was more common in women than in men (31.0% vs 25.8%, P=0.0035). However, the proportion of low adherence was comparable in men and women (41.7% vs 41.1%, P=0.7849).

An FDC treatment was thought to contribute to treatment goal attainment in 63.1% of all patients by improving adherence (45.1%), patient convenience (43.8%), cardiovascular protection (32.2%), LDL-C control (30.1%), BP control (26.2%), and costs (17.2%).

Logistic regression revealed that depression and smoking are strongly associated with poor adherence (P<0.0001), independent of using the categorized MMAS-8 or the score as continuous variable. In the model of MMAS-8 score as continuous variable, additional but less strong associations with poor adherence were found for stroke (P=0.0456), age (men older than 55 years or women older than 65 years, P=0.0330), and positive family history of CAD (P=0.0213) and hypercholesterolemia (P=0.0041).

Blood pressure

The mean office SBP was 135.3±14.4 mmHg, and the mean DBP was 79.8±9.7 mmHg. BP control was achieved in 47.2% and 90.9% of the patients according to ESC/ESH guideline on hypertension (target <140/90 mmHg) and as assessed by the investigator, respectively (P<0.0001).

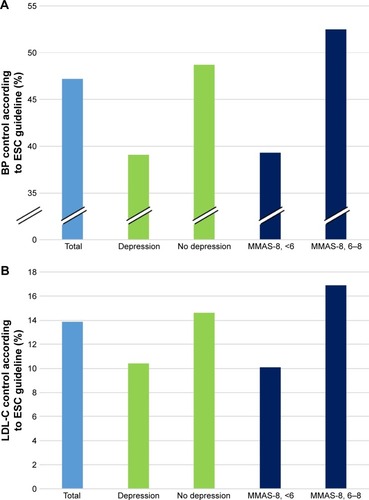

In patients with depression, BP was significantly higher and BP control was achieved in a significantly lower proportion of patients (SBP 138.1±15.6 vs 134.8±14.1 mmHg, DBP 81.8±10.4 vs 79.4±9.6 mmHg, BP control according to ESC guideline 39.1% vs 48.7%, for all comparisons P<0.0001, BP control according to investigator 87.7% vs 91.6%, P=0.0053). Patients with low adherence compared to those with moderate or high adherence had higher BP values and worse BP control according to ESC guideline and according to the treating physician’s assessment (SBP 137.9±13.9 vs 133.4±14.5 mmHg, DBP 81.8±9.6 vs 78.3±9.6 mmHg, BP control according to ESC guideline 40.8% vs 52.2%, BP control according to investigator 87.9% vs 93.4%, for all comparisons P<0.0001). BP was higher in women than in men (136.2±14.28 vs 134.9±14.24 mmHg, P=0.0255), and BP control was achieved in 47.4% of men and 45.7% of women (P=0.4032).

In logistic regression analyses, low adherence (MMAS-8 <6) was strongly associated with poor BP control, whereas a history of myocardial infarction was associated with better BP control (P<0.0001). An association with poor BP control was also found for depression (P=0.0211), renal disease (P=0.0065), and FDC antihypertensive treatment (P=0.0062).

The data are given in and . The comparisons of SBP in the six subgroups with low, moderate, and high adherence with and without depression are depicted in and indicate that SBP is related to both parameters. The results for DBP were comparable (not shown).

Figure 2 (A) SBP in patients with low, moderate, and high adherence with and without depression. (B) LDL-C levels in patients with low, moderate, and high adherence with and without depression.

Abbreviations: LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MMAS-8, Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Lipid-lowering medication, serum lipid levels, and LDL-C control

Mean total cholesterol was 193.9±52.6 mg/dL, LDL-C was 112.3±40.8 mg/dL, HDL-C was 54.1±29.2 mg/dL, and triglycerides were 148.6±93.7 mg/dL. LDL-C control was achieved in 13.9% and 75.8% according to ESC guideline and investigator, respectively (P<0.0001). The mean score of the MMAS-8 regarding lipid-lowering medication was 5.6±2.3.

Patients with depression were characterized by significantly higher LDL-C levels compared to patients without depression (116.4±42.0 vs 111.5±40.5 mg/dL, P=0.0238) and had a lower probability of achieving LDL-C control according to ESC guideline (10.4% vs 14.6%, P=0.0114). LDL-C control as reported by the treating physician was not different between the groups (78.4% vs 75.3%, P=0.1269). In addition, triglycerides were significantly higher in patients with depression (161.2±93.8 vs 146.1±93.5 mg/dL, P=0.0032). The proportion of patients taking statins, ezetimibe, or other lipid-lowering medication was comparable. Patients with low adherence to lipid-lowering medication showed significantly higher LDL-C levels compared to patients with moderate or high adherence (120.8±42.4 vs 105.5±38.3 mg/dL, P<0.0001). A smaller proportion of patients with low adherence achieved LDL-C control (LDL-C control according to ESC guideline 10.1% vs 16.9% P<0.0001, LDL-C control according to investigator 72.4% vs 78.4%, P=0.0001). Patients with low adherence had higher levels of triglycerides (162.8±94.4 vs 136.6±90.8, P<0.0001). The proportion of patients taking statins, ezetimibe, or other lipid-lowering medication was comparable. Women had higher LDL-C levels than men (120.3±43.6 vs 109.1±38.86 mg/dL, P<0.0001), whereas in men triglycerides were higher (152.9±97.15 vs 142±86.7 mg/dL, P=0.0081) and HDL-C was lower (51.4±28.57 vs 57.9±24.45 mg/dL, P<0.0001). LDL-C control according to guideline was documented in 15.5% of men and 10.8% of women (P=0.0006).

Logistic regression revealed that male sex (P=0.0006), stroke (P=0.0014), and statin/ezetimibe single-pill combination treatment (P=0.0005) were associated with better LDL-C control, whereas depression (P=0.0452), renal disease (P=0.0071), and low adherence (MMAS-8 <6, P=0.0015) were associated with worse LDL-C control. The data are given in and .

Table 2 Serum lipid levels, LDL-C control, and lipid-lowering medication for the total population, patients with vs without depression, and patients with low vs moderate or high adherence to lipid-lowering medication

The comparisons of LDL-C levels in the six subgroups with low, moderate, and high adherence with and without depression are depicted in and indicate that serum LDL-C levels are related to both parameters.

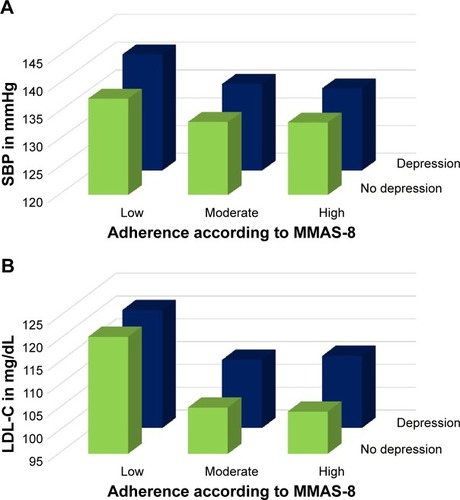

Comparison of adherence to BP- vs lipid-lowering medication

The results of the MMAS-8 scores for BP- and lipid-lowering medication were compared and showed a significant correlation (, Spearman’s correlation coefficient 0.92059, P<0.0001).

Discussion

This study reports three important findings. The data demonstrate that low self-reported medication adherence is strongly associated with insufficient LDL-C and BP control. The information on medication adherence can be reliably obtained in daily practice using the MMAS-8 questionnaire. Second, the clinical diagnosis of depression is associated with low LDL-C and BP target attainment. Low adherence and depression identify individuals among the cardiovascular high-risk population who might benefit from intensified care. Third, adherence to lipid-lowering medication correlates with adherence to BP-lowering medication. This information extends previous data from the literatureCitation10,Citation11,Citation16,Citation17,Citation25 on medication adherence to the situation in lipid lowering, which is closely associated with BP control.

Control of LDL-C as recommended by the current ESC/EAS guidelineCitation4 was achieved in only 13.9% of the patients in this study. The poor LDL-C control is in line with previous reports of LDL-C goal attainment in USA and in Europe, which ranges between 20% and 30%.Citation5,Citation7,Citation26–Citation28 As shown recently, potentially 73.9% of all patients at very high risk are able to reach the LDL-C goal of <70 mg/dL if high-dose statins and ezetimibe are used at appropriate doses.Citation29 Similarly, the ESC/ESH BP targets are achieved in only 50%–60% of the patients in USA and in Europe.Citation7,Citation23,Citation30,Citation31

Several reasons for the underutilization of well-proven therapies in daily practice have been discussed. One frequent reason for not prescribing or up-titrating statins is worries about potential side effects, although observed side effects occur infrequently and have been shown not to outweigh the beneficial effects.Citation32–Citation34 In addition, our data show a lack of awareness regarding the guideline-recommended target values, reflected in our study by the treating physician’s self-reported assessment of LDL-C control being achieved in 75.8% of the patients. Similarly, BP control was thought to be achieved in 90.9% of the patients when judged by treating physician as compared to 47.2% according to the current ESC/ESH guideline. The discrepancy in BP control between guideline recommendation and physicians’ assessment is not of the same magnitude compared to the assessment of LDL-C control, indicating a different grade of awareness and implementation of the guideline recommendations. This is further underpinned by the fact that poor BP control was much stronger associated with poor medication adherence as patient-related factor than poor LDL-C control was, indicating that physicians’ inertia is one main factor in poor LDL-C control. This interesting and novel finding indicates an important opportunity for future educational activities.

In light of revised BP targets, the number of patients with controlled hypertension may become even worse.Citation35,Citation36 It is indeed essential to stress the importance of BP lowering to reduce major cardiovascular end points and mortality. Based on a meta-analysis including more than 600,000 patients, an office BP reduction of 10 mmHg is associated with an RR reduction in CAD by 17%, stroke by 27%, heart failure by 27%, and mortality by 13%, respectively.Citation37

There are different methods for assessing adherence such as electronic measures, pharmacy refills, plasma/urine drug and/or metabolite concentrations, pill counts, and self-report.Citation38 Importantly, differences in the estimated adherence depend on the method used.Citation39 The MMAS-8 self-reported questionnaire has the advantage of being relatively quickly to answer, easily applicable, and low cost for use in daily practice.Citation40,Citation41

In our study, patients with low adherence to lipid-lowering medication were younger than those with moderate or high adherence. This is in line with studies in patients with chronic heart failure and hypertension.Citation25,Citation42 Furthermore, patients with low adherence had more CVD risk factors such as smoking, hypercholesterolemia, peripheral vascular disease, and positive family history of CAD. Therefore, these young patients are at high risk for the development and progression of CVD with a high potential for improvements in primary and secondary prevention by improved adherence. The abovementioned findings support the concept of the “healthy adherer effect”, meaning that high medication adherence is a surrogate marker for overall healthy behavior.Citation43,Citation44

Our results confirm that low adherence correlates with fewer patients reaching LDL-C control.Citation45 In our study, the rates of goal attainment did not differ significantly between moderate and high adherence, indicating that there is a certain extent of adherence which should not be undercut to reach a treatment goal. A similar result was reported by Chi et al.Citation15 A possible explanation is that LDL-C lowering can still occur when doses are missed by patients with moderate adherence.

Low adherence to lipid-lowering medication not only did result in worse LDL-C control but also was associated with insufficient BP control in patients treated with antihypertensive drugs, further increasing cardiovascular risk. Our study suggests that adherence to BP-lowering medication may predict the intake of lipid-lowering medication. This finding has very important practical implications. Although several studies have proved that FDCs reduce BP to a greater extent compared to the components given separately,Citation46–Citation48 this type of information is missing for lipid-lowering medications, eg, statin–ezetimibe combinations. The observed robust correlation of the MMAS-8 questionnaires for lipid- and BP-lowering medication implies that the data on the potential benefit of FDCs may be extrapolated from BP to lipid lowering.

Another important finding of our study is that patients with past or present depression are less likely to achieve the guideline-recommended LDL-C goal.Citation22,Citation49 Patients with depression had more risk factors for CVD such as smoking or past stroke and are therefore at even higher risk for progressive CVD. Noteworthy, the treating physician’s assessment of LDL-C control did not differ between patients with vs without depression in contrast to the goal attainment according to guideline, which was significantly worse in patients with depression. One might suggest that the symptoms attributable to depression may have been dominant in the patients’ treatment, potentially distracting from somatic problems. Patients with depression may benefit from the treatment of depression by an improvement in medication adherence.Citation50

Our study shows a higher prevalence of depression in women (23.9% vs 11.4% in men). Although depression was strongly associated with adherence, sex was no predictor of poor adherence. This is further underpinned by a comparable proportion of men and women with achieved BP control, which was strongly associated with adherence. LDL-C control was worse in women. Poor LDL-C control in women seems to be driven by depression rather than poor adherence, suggesting that especially in women LDL-C is an underappreciated risk factor prone to physicians’ inertia.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. The cross-sectional study design carries limited possibilities for exploring causal relationships and does not provide clinical follow-up. The consecutive inclusion of the patients was not supervised; therefore, selection bias was possible. Depression was not diagnosed using special questionnaires or diagnostic criteria, but was assessed according to the treating physician’s diagnosis; however, this reflects the situation in daily practice. Similarly, the self-reported MMAS-8 is less precise and overestimates adherence compared to electronic monitoring, pharmacy claims, or refill data or by measuring drug/metabolite levels in the blood and/or urine;Citation38 however, the advantage of the method is the feasibility and practicality in daily practice that we documented in our study.

Conclusion

The majority of patients at high cardiovascular risk did not reach the guideline-recommended LDL-C und BP goals. Low adherence and the diagnosis of depression identified individuals at risk for reduced LDL-C and BP control who are likely to benefit from intensified care. Self-reported medication adherence can be easily obtained in daily practice.

Author contributions

JLK and UL designed the study and wrote the article. All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by Servier Deutschland GmbH, Germany. Statistical analyses were supported by Pharmalog, Institut für klinische Forschung GmbH, Oskar-Messter-Straße 29, Ismaning, Germany.

Disclosure

Julius L Katzmann reports grants from Servier Deutschland GmbH, Germany, non-financial support from Pharmalog, Institut für klinische Forschung GmbH, Oskar-Messter-Straße 29, Ismaning, Germany, during the conduct of the study; Michael Böhm reports personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Bayer, personal fees from Servier, personal fees from Medtronic, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, nothing from Vifor, personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, outside the submitted work; and Ulrich Laufs report other from Servier, during the conduct of the study. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health Organization [homepage on the Internet]Global Health Observatory (GHO) data Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/mortality_morbidity/en/Accessed May 21, 2018

- CollinsRReithCEmbersonJInterpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapyLancet2016388100592532256127616593

- BaigentCKeechAKearneyPMCholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) CollaboratorsEfficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statinsLancet200536694931267127816214597

- CatapanoALGrahamIdeBacker GESC Scientific Document Group2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of DyslipidaemiasEur Heart J201637392999305827567407

- ChiangCEFerrièresJGotchevaNNSuboptimal Control of Lipid Levels: Results from 29 Countries Participating in the Centralized Pan-Regional Surveys on the Undertreatment of Hypercholesterolaemia (CEPHEUS)J Atheroscler Thromb201623556758726632163

- GittAKLautschDFerrieresJLow-density lipoprotein cholesterol in a global cohort of 57,885 statin-treated patientsAtherosclerosis201625520020927667299

- KotsevaKWoodDDe BacquerDEUROASPIRE InvestigatorsEUROASPIRE IV: A European Society of Cardiology survey on the lifestyle, risk factor and therapeutic management of coronary patients from 24 European countriesEur J Prev Cardiol201623663664825687109

- OsterbergLBlaschkeTAdherence to medicationN Engl J Med2005353548749716079372

- EganBMLiJQanungoSWolfmanTEBlood pressure and cholesterol control in hypertensive hypercholesterolemic patients: national health and nutrition examination surveys 1988–2010Circulation20131281294123817481

- EwenSMeyerMRCremersBBlood pressure reductions following catheter-based renal denervation are not related to improvements in adherence to antihypertensive drugs measured by urine/plasma toxicological analysisClin Res Cardiol2015104121097110526306594

- SchulzMKruegerKSchuesselKMedication adherence and persistence according to different antihypertensive drug classes: A retrospective cohort study of 255,500 patientsInt J Cardiol201622066867627393848

- KurlanskyPHerbertMPrinceSMackMCoronary Artery Bypass Graft Versus Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Meds Matter: Impact of Adherence to Medical Therapy on Comparative OutcomesCirculation2016134171238124627777293

- DaskalopoulouSSDelaneyJAFilionKBBrophyJMMayoNESuissaSDiscontinuation of statin therapy following an acute myocardial infarction: a population-based studyEur Heart J200829172083209118664465

- De VeraMABholeVBurnsLCLacailleDImpact of statin adherence on cardiovascular disease and mortality outcomes: a systematic reviewBr J Clin Pharmacol201478468469825364801

- ChiMDVansomphoneSSLiuILAdherence to statins and LDL-cholesterol goal attainmentAm J Manag Care2014204e105e11224884955

- CorraoGParodiANicotraFBetter compliance to antihypertensive medications reduces cardiovascular riskJ Hypertens201129361061821157368

- MazzagliaGAmbrosioniEAlacquaMAdherence to antihypertensive medications and cardiovascular morbidity among newly diagnosed hypertensive patientsCirculation2009120161598160519805653

- ChowdhuryRKhanHHeydonEAdherence to cardiovascular therapy: a meta-analysis of prevalence and clinical consequencesEur Heart J201334382940294823907142

- BöhmMSchumacherHLaufsUEffects of nonpersistence with medication on outcomes in high-risk patients with cardiovascular diseaseAm Heart J20131662306.e1314.e123895814

- ShepsDSSheffieldDDepression, anxiety, and the cardiovascular system: the cardiologist’s perspectiveJ Clin Psychiatry200162Suppl 8126 discussion 17–8

- KhawajaISWestermeyerJJGajwaniPFeinsteinREDepression and coronary artery disease: the association, mechanisms, and therapeutic implicationsPsychiatry (Edgmont)2009613851

- DiMatteoMRLepperHSCroghanTWDepression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherenceArch Intern Med2000160142101210710904452

- ManciaGFagardRNarkiewiczK2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Eur Heart J201334282159221923771844

- MoriskyDEAngAKrousel-WoodMWardHJPredictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient settingJ Clin Hypertens (Greenwich)200810534835418453793

- GuptaPPatelPŠtrauchBBiochemical Screening for Nonadherence Is Associated With Blood Pressure Reduction and Improvement in AdherenceHypertension20177051042104828847892

- LaufsUKarmannBPittrowDAtorvastatin treatment and LDL cholesterol target attainment in patients at very high cardiovascular riskClin Res Cardiol2016105978379027120330

- FoxKMTaiMHKostevKHatzMQianYLaufsUTreatment patterns and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) goal attainment among patients receiving high- or moderate-intensity statinsClin Res Cardiol2018107538038829273856

- JonesPHNairRThakkerKMPrevalence of dyslipidemia and lipid goal attainment in statin-treated subjects from 3 data sources: a retrospective analysisJ Am Heart Assoc201216e00180023316314

- GittAKLautschDDe FerrariGHorackMBrudiPFerriéresJConsequent use of available oral lipid Lowering agents would bring the majority of high-risk patients with coronary heart disease to recommended targets: an estimate based on the DYSIS II StudyClin Res Cardiol2018107Suppl 1

- NeuhauserHKAdlerCRosarioASDiederichsCEllertUHypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control in Germany 1998 and 2008–11J Hum Hypertens201529424725325273858

- JoffresMFalaschettiEGillespieCHypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control in national surveys from England, the USA and Canada, and correlation with stroke and ischaemic heart disease mortality: a cross-sectional studyBMJ Open201338e003423

- MachFRayKKWiklundOEuropean Atherosclerosis Society Consensus PanelAdverse effects of statin therapy: perception vs. the evidence – focus on glucose homeostasis, cognitive, renal and hepatic function, haemorrhagic stroke and cataractEur Heart J201839272526253929718253

- SpenceJDDresserGKOvercoming challenges with statin therapyJ Am Heart Assoc201651e00249726819251

- ZhangHPlutzkyJShubinaMTurchinAContinued Statin Prescriptions After Adverse Reactions and Patient Outcomes: A Cohort StudyAnn Intern Med2017167422122728738423

- WheltonPKCareyRMAronowWS2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice GuidelinesJ Am Coll Cardiol20187119e127e24829146535

- WilliamsBManciaGSpieringWESC Scientific Document Group2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertensionEur Heart J201839333021310430165516

- EttehadDEmdinCAKiranABlood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysisLancet20163871002295796726724178

- JefferyRANavarroTWilczynskiNLAdherence measurement and patient recruitment methods are poor in intervention trials to improve patient adherenceJ Clin Epidemiol201467101076108225087180

- MorrisABLiJKroenkeKBruner-EnglandTEYoungJMMurrayMDFactors associated with drug adherence and blood pressure control in patients with hypertensionPharmacotherapy200626448349216553506

- LehmannAAslaniPAhmedRAssessing medication adherence: options to considerInt J Clin Pharm2014361556924166659

- HawksheadJKrousel-WoodMATechniques for Measuring Medication Adherence in Hypertensive Patients in Outpatient SettingsDis Manag Health Outcomes2007152109118

- KruegerKBotermannLSchorrSGGriese-MammenNLaufsUSchulzMAge-related medication adherence in patients with chronic heart failure: A systematic literature reviewInt J Cardiol201518472873525795085

- BöhmMLloydSMFordINon-adherence to ivabradine and placebo and outcomes in chronic heart failure: an analysis from SHIFTEur J Heart Fail201618667268326952245

- LaufsURettig-EwenVBöhmMStrategies to improve drug adherenceEur Heart J201132326426820729544

- BerminghamMHaydenJDawkinsIProspective analysis of LDL-C goal achievement and self-reported medication adherence among statin users in primary careClin Ther20113391180118921840055

- CastellanoJMSanzGPeñalvoJLA polypill strategy to improve adherence: results from the FOCUS projectJ Am Coll Cardiol201464202071208225193393

- Gwadry-SridharFHManiasELalLImpact of interventions on medication adherence and blood pressure control in patients with essential hypertension: a systematic review by the ISPOR medication adherence and persistence special interest groupValue Health201316586387123947982

- GuptaAKArshadSPoulterNRCompliance, safety, and effectiveness of fixed-dose combinations of antihypertensive agents: a meta-analysisHypertension201055239940720026768

- Krousel-WoodMJoyceCHoltEPredictors of decline in medication adherence: results from the cohort study of medication adherence among older adultsHypertension201158580481021968751

- BauerLKCaroMABeachSREffects of depression and anxiety improvement on adherence to medication and health behaviors in recently hospitalized cardiac patientsAm J Cardiol201210991266127122325974