Abstract

Purpose

To review the use of paliperidone palmitate in treatment of patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

Published clinical trial data for the development and utilization of paliperidone palmitate for the treatment of schizophrenia were assessed in this review. Four short-term, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials investigated the efficacy of paliperidone palmitate in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. Paliperidone palmitate was also studied as a maintenance treatment to prevent or delay relapse in stable schizophrenia. In addition, paliperidone palmitate was compared to risperidone long-acting injection for noninferiority in three studies.

Results

Paliperidone palmitate has been shown to be effective in reducing symptoms as measured by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total scores in the four acute treatment studies. In the maintenance treatment studies, paliperidone palmitate was found to be more effective than placebo in preventing or delaying the time to first relapse in stable schizophrenia patients. In addition, paliperidone palmitate was shown to be noninferior to risperidone long-acting injection in two studies. It was shown to be reasonably well tolerated in all clinical trials. Acute treatment phase should be initiated with a dose of 234 mg on day one and 156 mg on day eight, followed by a recommended monthly maintenance dose of 39–234 mg based on efficacy and tolerability results from the clinical studies.

Conclusion

Providing an optimal long-term treatment can be challenging. Paliperidone palmitate can be used as an acute treatment even in outpatient setting, and it has shown to be well tolerated by patients. Also, it does not require overlapping oral antipsychotic supplementation while being initiated, and is dosed once per month.

Introduction

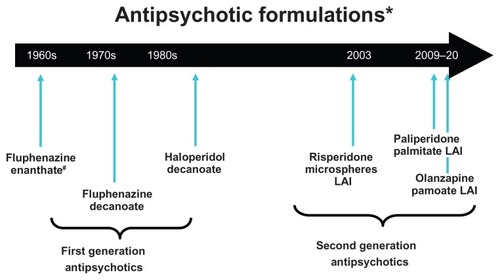

Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics have been available for many years but, until recently, options available were limited to first-generation “typical” antipsychotics. In the last decade, several formulations of the newer, second-generation “atypical” antipsychotics have become available (). The goal of this review is to discuss the pharmacotherapy and clinical pharmacology of LAI antipsychotic therapies with a focus on paliperidone palmitate, a newer second-generation antipsychotic formulated for LAI.

Figure 1 Timeline of availability of long-acting antipsychotic formulations that are Food and Drug Administration approved for use in the United States; other first-generation long-acting injectables are available in other countries.

Abbreviation: LAI, long-acting injection.

LAI antipsychotic formulations

LAI antipsychotics are useful maintenance treatment options in patients with schizophrenia. These therapies have been available since the 1960s when the first-generation antipsychotic agent, fluphenazine, was introduced as a long-acting enanthate formulation. The commonly used fluphenazine decanoate and haloperidol decanoate long-acting agents soon followed. These agents are synthesized such that the parent drug is esterified to fatty acid chains that allow the formulation to be dissolved in sesame oil. Administration of the oily solution into deep muscle tissue as a “depot” injection results in a pool of medication that is subsequently hydrolyzed through an inflammatory response, which releases the drug into systemic circulation.Citation1 Other available first-generation depot agents include perphenazine, pimozide, and flupenthixol. However, only fluphenazine and haloperidol are available agents in the United States due to Food and Drug Administration restriction.Citation1 Second-generation LAIs such as risperidone microspheres, olanzapine pamoate, and paliperidone palmitate have also been formulated to gradually release active drug into the plasma from deep-tissue intramuscular injections. Unlike the sesame seed oil formulations of their first-generation predecessors, alternative delivery systems have been developed that no longer need to rely on covalent esterification to a fatty acid moiety. The paliperidone LAI formulation is the palmitate salt ester of paliperidone (9-OH-risperidone), and uses a nanocrystal technology formulation. In the pharmaceutical arena, nanoparticles are defined as having a size between 1–1000 nm. In this context, tiny drug crystals are created and dispersed in liquid media as an aqueous suspension (nanosuspensions).Citation2 Paliperidone palmitate is a mixture of paliperidone palmitate enantiomers “wet-milled” into nanoparticles, which have low water solubility.Citation3 After intramuscular injection, the suspended palmitate salt conjugates are hydrolyzed to the active drug, which dissolves slowly into the systemic circulation. Due to the low solubility, slow dissolution occurs at the injection site.Citation4

Paliperidone palmitate pharmacokinetics

The release of the drug into the systemic circulation begins as early as the first day of administration, and continues for up to 126 days. The apparent volume of distribution of paliperidone is 391 L based on population pharmacokinetic analyses. The plasma protein binding of racemic paliperidone is 74%.Citation3

After a single intramuscular dose, plasma concentrations of paliperidone rise to reach maximum plasma concentration at a median time to maximum concentration of 13 days.Citation4 Four metabolic pathways of paliperidone have been identified in vivo: (1) dealkylation, (2) hydroxylation, (3) dehydrogenation, and (4) benzisoxazole scission.Citation5 In vitro studies in human liver microsomes revealed that paliperidone palmitate does not appreciably inhibit the metabolism of drugs metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) isozymes and is not significantly metabolized by CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CPY2C8/9/10, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, CYP3A4, and CPY3A5.Citation3,Citation5 Paliperidone is predominantly excreted by the kidneys. According to paliperidone palmitate product labeling, 1 week following administration of a single oral dose of 1 mg immediate- release 14C-paliperidone, 59% of the dose was excreted unchanged into urine, indicating that paliperidone is not extensively metabolized in the liver. Approximately 80% of the administered radioactivity was recovered in urine and 11% in feces.Citation5,Citation6 Therefore, it is not expected to precipitate clinically significant pharmacokinetic interactions with other drugs. The median half-life of paliperidone following a single intramuscular dose of paliperidone palmitate (39–234 mg) is 25–49 days.

The pharmacokinetic profile of paliperidone palmitate may be influenced by factors such as injection site, injection volume, needle length, creatinine clearance, and body mass index (BMI).Citation4 The most clinically relevant factor in this list is injection site. Two studies identified that deltoid muscle injections, compared to gluteal administration, resulted in higher initial median paliperidone plasma concentrations on day eight of treatment (after the second injection).Citation4,Citation7 Intramuscular injection into the deltoid muscle resulted in a maximum plasma concentration that was 28% greater than the same dose administered into the gluteus.Citation4 Once at steady state, there appears to be little difference in plasma paliperidone concentration between the two injection sites.Citation7 This is important for clinicians to recognize because this greater maximum plasma concentration from the deltoid facilitates a rapid time to steady-state plasma concentrations, which is why deltoid administration is recommended for the first two injections. After the first two injections, patients and providers have a choice between deltoid and gluteal injection sites. It is also important to note that this may be a time when patients are more likely to experience side effects associated with peak plasma concentrations and to communicate with patients and caregivers appropriately. This certainly may apply to other LAI agents and is a general issue associated with LAIs. These studies also noted that using a longer needle (1.5 inch versus 1 inch) improved the likelihood of delivering accurate injections and, furthermore, that accuracy appears to be better from the deltoid site as compared to the gluteal route where the “hypovascularity” of subcutaneous tissue may alter the release profile of the drug.Citation4,Citation7

Reduced creatinine clearance is an indicator of renal dysfunction and therefore, is inversely correlated with the renal clearance of paliperidone. The results from pharmacokinetic analyses of oral paliperidone identified that the total clearance of the drug was reduced by 32% in those with mild renal impairment, 64% in those with moderate impairment, and 71% in those with severe impairment.Citation4 When this information is translated to clinical application, creatinine clearance values < 80 mL/minute influence the dosing of the drug, as summarized in the “Dosing and Clinical Utilization” section below.

BMI is also related to pharmacokinetic parameters of paliperidone palmitate during the initial stages of treatment. Early in treatment, patients with higher baseline BMIs (<25 kg/m2) exhibit approximately 1.5–2-times lower median paliperidone plasma concentrations on day eight and day 36 than patients with normal baseline BMI (<25 kg/m2) who are administered 156 mg injections.Citation8 However, the differences between higher and lower BMI groups do not appear to persist after repeated injections and may, therefore, not be of great clinical significance for longer-term treatment.

Paliperidone palmitate pharmacodynamics

Paliperidone palmitate is a centrally acting dopamine-D2 (D2) receptor antagonist and a serotonin type-2A (5-HT2A) receptor antagonist. It is also active as an antagonist at α1 and α2 adrenergic receptors and histamine type-H1 receptors. Paliperidone palmitate has little affinity for cholinergic muscarinic or β1 and β2 adrenergic receptors.Citation9 Comparisons with other antipsychotics with long-acting formulations that are available in the United States are presented in . Receptor binding profiles are often clinically helpful for clinicians when assessing the likelihood for specific side effects based on prior experiences with other agents. The first-generation haloperidol and fluphenazine antipsychotics are known for high D2 affinity and lower histamine type-1/serotonin type-2C affinity, which is thought to be associated with a lower likelihood for weight gain than second-generation alternatives. Similarly, high D2 affinity in the absence of significant 5-HT2A affinity is thought to be an underlying mechanism of a greater likelihood of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) for these first-generation agents as compared to second-generation options. Paliperidone has a similar receptor binding profile as risperidone, thus the choice between these two agents in a long-acting formulation may be more related to dosing logistics (once monthly for paliperidone versus every 2 weeks for risperidone) or insurance coverage/financial considerations.

Table 1 Receptor binding affinities (based on Ki values) of long-acting antipsychotic injectionsCitation19,Citation45

Clinical studies of paliperidone palmitate

The efficacy and safety of paliperidone palmitate in the acute treatment of schizophrenia has been assessed in one 9-week and three 13-week double-blind, randomized, placebocontrolled, fixed-dose studies.Citation8,Citation10–Citation12 Prevention of relapse in schizophrenia was assessed in two long-term maintenance studies.Citation13,Citation14 Paliperidone palmitate has also been compared with risperidone LAI in three noninferiority studies.Citation15–Citation17

All clinical trials of paliperidone palmitate summarized herein used Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total scores as primary outcome variables with additional analyses of positive and negative subscale measures of this assessment. Secondary outcome measures in these studies included the Clinical Global Impression of Severity (CGI-S) scale and the Personal and Social Performance (PSP) scale, which measures the severity of functional deficits. Recurrence and relapse events were evaluated in the long-term maintenance studies using fairly standard a priori criteria for relapse or impending relapse.

Acute treatment

Four (one 9-week and three 13-week) multicenter, doubleblind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose studies evaluated the safety and efficacy of paliperidone palmitate using doses ranging from 39–234 mg in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. The fixed doses of paliperidone palmitate in these studies were given on days one, eight, and 36 in the 9-week study, and additionally on day 64 of the 13-week studies. One study used the currently recommended initiation dose of 234 mg of paliperidone palmitate or matching placebo via deltoid route on day one.Citation12 Safety and efficacy were assessed in the 9-week study, while the three 13-week studies were specifically designed as dose-response studies.Citation8,Citation10–Citation12

The first multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, dose-response study was a 13-week, phase III trial of 388 patients with schizophrenia. These patients had a diagnosis of schizophrenia – as established by the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) – for at least 1 year before screening, a PANSS total score at baseline between 70–120, and a BMI >17.0 kg/m2. Otherwise, the patients were reported to be in good health.Citation8 As summarized in , participants were treated with paliperidone palmitate 78 mg, 156 mg, or 234 mg versus placebo with PANSS assessments completed before and after completion of the treatment. PANSS total scores for participants in the 78 mg group did not differ from placebo. Only the paliperidone palmitate 156 mg dose treatment group showed significantly greater improvement in PANSS total score compared with placebo (P < 0.02). Secondary efficacy findings included significant improvement in PSP scores from baseline to endpoint for both the paliperidone palmitate 156 mg (P < 0.001) and 78 mg (P = 0.004) groups.

Table 2 Paliperidone palmitate clinical trials of treatment for acute schizophrenia

The mean (standard deviation [SD]) PSP score change from baseline for the paliperidone palmitate 156 mg and 78 mg groups was 4.8 (15.35) and 4.2 (13.21), respectively. CGI-S scale improvements were significant only in the paliperidone palmitate 156 mg group (P = 0.01); however, the median decrease in CGI-S was 1.0 for both treatment groups. Due to medication kit allocation error in the paliperidone palmitate 234 mg dose group, the efficacy and safety results for this group were not presented.

The second acute treatment study assessed the efficacy and safety of paliperidone palmitate compared to placebo in 247 patients.Citation10 This was a 9-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study where patients were randomized to receive gluteal injections of either placebo or fixed doses of 78 mg or 156 mg on days one, eight, and 36. Patients participating in this study had a diagnosis of schizophrenia – according to DSM-IV-TR criteria – for at least 1 year, a PANSS total score of 70–120 at screening (60–120 inclusive on day one before the start of the study), and a BMI range of 15–35 kg/m2. As summarized in , participants treated with either dose of paliperidone palmitate had significant improvements from baseline in PANSS total score compared with placebo (P ≤ 0.001, each dose versus placebo). Differentiation from placebo was identified at day eight, and maintained to endpoint for both doses. Mean PANSS total scores showed significant improvement at endpoint for both paliperidone palmitate treatment groups. In the paliperidone palmitate 78 mg and 156 mg groups, the mean PANSS difference was −5.2 and −7.8, respectively. CGI-S scores also improved at endpoint where 50% of the placebo group had a rating of marked, severe, or extremely severe at endpoint versus 37% and 32% for the paliperidone palmitate 78 mg and 156 mg groups, respectively. Both paliperidone palmitate treatment doses were statistically superior to placebo in reducing CGI-S scores (P ≤ 0.004).

The third multicenter, randomized, double-blind study of paliperidone palmitate and placebo assessed efficacy, safety, and tolerability over a 13-week treatment period.Citation11 Fixed doses of 39 mg, 78 mg, and 156 mg paliperidone palmitate versus placebo were administered as gluteal injections on days one and eight, and then every 4 weeks (days 36 and 64) in 518 adult patients. Patients participating in this study had similar eligibility as in prior studies, ie, meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia for at least 1 year. At enrollment, patients had a PANSS total score of 70–120 with a BMI > 15.0 kg/m2. Of the 518 randomized patients, only 263 (51%) patients completed the study. As noted in , all paliperidone palmitate dose groups showed significant improvement versus placebo in the primary efficacy measurement of PANSS.

Interestingly, a notable disparity was detected in the distribution of baseline BMI across participating countries, but not across treatment groups: 75% of United States patients were obese (BMI < 30 kg/m2) or overweight (BMI < 25–30 kg/m2) compared to 42% of Romanian, 41% of Russian, 35% of Bulgarian, and 23% of South African participants. The mean baseline BMI of patients from the United States was 30.2 kg/m2 (range 17–60 kg/m2) compared with 24.2–30.2 kg/m2 (range 16–38 kg/m2) for participants from other countries. Patients enrolled at sites outside the United States had greater improvements in PANSS total scores than those from sites in the United States. This finding indicated a trend towards differential treatment effect by BMI category. Based on pharmacokinetic data summarized earlier, this may have resulted in differences in plasma concentrations early in treatment.

The final efficacy and safety study of paliperidone palmitate was a 13-week investigation of 652 patients with schizophrenia.Citation12 This was a multicenter, randomized, doubleblind, and placebo-controlled investigation where participants received paliperidone palmitate at 234 mg or placebo in the deltoid muscle on day one, with assigned fixed dose or placebo in the deltoid or gluteal muscle on day eight, and then once monthly. Patients participating in this study included patients with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia with total PANSS scores of 60–120 at baseline. Patients with BMI < 40 kg/m2 were excluded from this study. A total of 652 patients were randomly assigned (1:1:1:1) to each dose group of 39 mg, 156 mg, or 234 mg paliperidone palmitate or placebo. PANSS total score from baseline to endpoint improved significantly in all three dose groups versus placebo (P ≤ 0.034). The mean PSP scores showed a dose-related improvement in the paliperidone palmitate treatment groups, which was significant in the 156 mg and 234 mg groups. Mean (SD) changes in PSP scores from baseline to endpoint were noted as follows: 2.9 (15.3) in the 39 mg group, 6.1 (13.6) in the 156 mg group, 8.3 (14.7) in the 234 mg group versus 1.7 (15.6) in the placebo group. A significant improvement in CGI-S scores was seen only in the paliperidone palmitate 156 mg and 234 mg groups (P ≤ 0.005). The median (range) changes in CGI-S from baseline were noted as follows: −1.0 (−3;2) in the 39 mg group, −1.0 (−4;2) in the 156 mg group, and −1.0 (−4;3) in the 234 mg group compared to 0.00 (−3;2) in the placebo group.

Maintenance treatment

Relapse prevention in schizophrenia was assessed in a long-term maintenance study of recurrence prevention consisting of five phases which were summarized and published as part of two analyses.Citation13,Citation14 These five phases included: (1) a screening and oral tolerability testing phase of up to 7 days, (2) a 9-week open-label transition phase during which eligible patients were switched from their previous antipsychotic to receive once-monthly injections of paliperidone palmitate, (3) a 24-week open-label maintenance phase, (4) a double-blind phase when stabilized patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either paliperidone palmitate or placebo until they experienced relapse, and finally (5) an optional 52-week open-label extension phase.Citation14 This long-term maintenance study was the most extensive clinical trial program of any LAIs to date.

In the first phase of the study, participating patients had a diagnosis of schizophrenia – per DSM-IV-TR criteria – for at least 1 year before screening and a PANSS total score < 120 at screening and baseline.Citation13 Both symptomatic and stable patients were eligible. The patients remained in the double-blind phase until they experienced a relapse, withdrew from the study, or until the first phase of the study was completed. The primary efficacy variable was the time-to-first relapse during the double-blind phase. Relapse was predefined as “time to first emergence” of one or more of the following: “significant” increase in total PANSS scores, psychiatric hospitalization, deliberate self-injury, violent behavior, and suicidal ideation. This study also evaluated changes in total PANSS and CGI-S scores.

The participants who were randomized to continue on paliperidone palmitate during the double-blind phase experienced a significant delay in time-to-relapse compared to the placebo group. The median time-to-relapse in the placebo group (50% of patients) was 163 days, and not estimable for paliperidone palmitate due to the small number of relapses observed (<25% of patients experienced a relapse). Relapse event rates were also significantly lower in the treatment group versus the placebo group (10% versus 34%, respectively). Of note, this study was terminated early by an Independent Data Monitoring Committee because of the robust findings identified in the interim efficacy results in favor of the paliperidone treatment group.

Patients from the above double-blind study who experienced a relapse remained relapse free until the double-blind study stopped early for efficacy, and those who completed the double-blind study were eligible for an open-label extension study of 52 weeks, which is the longest published study of paliperidone palmitate to date.Citation14 A total of 388 patients participated in this open-label extension and 288 patients (74%) completed the study. Patients received gluteal injections of paliperidone palmitate once every 4 weeks at a starting dose of 78 mg followed by 39 mg, 78 mg, 117 mg, or 156 mg flexible dosing. Improvements seen from baseline to endpoints were observed on PANSS, PSP scale, and CGI-S assessment. This study demonstrated improvements in PANSS total scores from baseline for patients treated with paliperidone palmitate (mean change ± SD −4.3 ± 15.43). The greatest improvement in PANSS total scores were seen in patients who were switched from placebo to paliperidone palmitate during the open-label extension study (mean change ± SD −8.4 ± 19.43). Overall, 6% (n = 22) of patients discontinued the study due to lack of efficacy, and worsening of schizophrenia was reported by 6% of the patients. Of the 61% of patients (n = 235) who were continuously exposed to paliperidone palmitate from the start of the transition phase to the end of the open-label extension study, 70% had >1.5 years of continuous exposure and 33% had >2 years of continuous exposure. The most frequently used paliperidone palmitate dose was 156 mg. The results of this study demonstrated that paliperidone palmitate administered as a once-monthly gluteal injection was well tolerated and accepted by patients who continued treatment for a year.

Comparative trials

Paliperidone palmitate has been studied in three comparative efficacy trials with risperidone LAI.Citation15–Citation17 These studies were designed as noninferiority trials with similar efficacy outcomes observed between the two agents.

The first comparative efficacy study was a 53-week, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, multicenter trial to assess noninferiority of paliperidone palmitate compared to risperidone LAI in patients with schizophrenia.Citation15 Primary efficacy outcome variables included changes on the PANSS total scores as well as relapse. Participants received flexible dosing of paliperidone palmitate 39–156 mg once-monthly injection or risperidone LAI biweekly injections of 25 mg on days eight and 22, and 25–50 mg flexible dosing starting from day 36, with allowed oral supplementation. Patients in the risperidone LAI group also received oral risperidone supplementation doses of 1–6 mg/day during the first 4 weeks of treatment and 1–4 mg/day at any dose increase for up to 3 weeks.

The mean change (±SD) from baseline to endpoint in PANSS total score was lower (−11.6 ± 21.22) in the paliperidone palmitate group compared to the risperidone LAI group (−14.4 ± 19.76). Relapse occurred in 25% of patients in the paliperidone palmitate group and 18% of patients in the risperidone LAI group. The overall rates of treatment-emergent adverse events were similar in the paliperidone palmitate (76%) and risperidone LAI (79%) groups. In the efficacy comparison, paliperidone palmitate-treated participants demonstrated a less favorable response as compared to risperidone LAI; however, it is important to note that the doses of paliperidone palmitate used in this study may have been suboptimal or at least perhaps comparatively lower than risperidone LAI when conventional conversion estimates are applied.

The next comparative efficacy study was a 13-week international, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, active-controlled, parallel-group, flexible-dose trial designed to assess noninferiority of paliperidone palmitate versus risperidone LAI in adult patients with schizophrenia.Citation16 In this study, patients were randomized to receive either paliperidone palmitate or risperidone LAI. Patients received paliperidone 234 mg via deltoid intramuscular route on day one, 156 mg on day eight, and then once-monthly flexible doses. Risperidone LAI subjects received their first injection of 25 mg on day eight followed by a biweekly injection on days 22, 36, 50, 64, and 78. Risperidone LAI patients received 1–6 mg/day oral risperidone on days 1–28, whereas paliperidone palmitate patients received oral placebo. The mean (SD) PANSS total score change from baseline was similar in the two groups starting on day four: −18.6 (15.45) in the paliperidone palmitate group and −17.9 (14.24) in the risperidone LAI group. The primary and secondary efficacy findings of this study resulted in similar improvements in patients with acute schizophrenia. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events was similar in both treatment groups (57.9% in the paliperidone palmitate group and 52.8% in the risperidone LAI group). The frequency of study drug discontinuation was low in both treatment groups (3% in the paliperidone palmitate group and 1.2% in the risperidone LAI group). Akathisia (both groups < 5%) and tremor (both groups < 3%) were the most commonly reported EPS-related adverse events, with no difference between the groups. The analysis of this study provided support for the conclusion that paliperidone palmitate has a similar efficacy (per noninferiority analysis) to risperidone.

The final comparison study published to date was an open-label, single-blinded, parallel-group, noninferiority study of paliperidone palmitate and risperidone LAI in adult Chinese patients with acute schizophrenia.Citation17 Eligible patients (N = 452) with schizophrenia were randomized (1:1) to receive either paliperidone palmitate or risperidone LAI for 13 weeks. Paliperidone palmitate doses were administered using a flexible dosing strategy including 78 mg, 156 mg, or 234 mg. Risperidone LAI was also dosed flexibly. Risperidone LAI-treated patients received oral risperidone supplementation of 1–6 mg/day at initiation, with risperidone LAI dose increases. The mean dose administered to individual patients throughout the study was 115.8 (range 87.5–137.5) mEq (the mean dose of 115.8 mEq is equal to a dose of approximately 180 mg as measured by currently approved doses) for the paliperidone palmitate group and 29.8 mg (range 25–37.5) for the risperidone LAI group. The mean change in total PANSS scores from baseline was −23.6 for the paliperidone palmitate group and −26.9 for the risperidone LAI group. The mean CGI-S scale change from baseline to endpoint was −1.5 in the paliperidone palmitate group and −1.7 in the risperidone LAI group. This study also demonstrated similar efficacy for paliperidone palmitate and risperidone LAI according to noninferiority analyses.

Safety and tolerability findings

The most common paliperidone palmitate-associated adverse events from pooled analyses of double-blind, placebocontrolled, acute treatment trials (rates of <5% in the treatment group and more than twice the placebo rate) were: EPS (0%–5% versus 1%), injection site-reactions (0%–10% versus 2%), dizziness (2%–6% versus 1%), and somnolence/sedation (5%–7% versus 3%).Citation3 The frequency of subjects who discontinued due to adverse events in the four fixed-dose, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials was reported to be 5.0% and 7.8% for paliperidone palmitate versus placebo, respectively.Citation8,Citation10–Citation12 In the 52-week open-label extension study, the most frequent adverse events were insomnia (7%), worsening of schizophrenia (6%), nasopharyngitis (6%), headache (6%), and <7% weight increase of baseline body weight (6%).Citation14 Taken as a whole, these findings suggest that paliperidone palmitate is relatively well tolerated in the context of these clinical trials.

EPS-related adverse events

In the largest 13-week dose-response study to date, akathisia was the most commonly reported EPS event across all the treatment groups (<6% of patients).Citation12 In both shorter term 9–13 week trialsCitation8,Citation10–Citation12 and maintenance treatment studies,Citation13,Citation14 the incidence of EPS-related events was <10% across paliperidone dose groups suggesting a favorable EPS tolerability profile for most patients.

Weight changes

Metabolic effects such as weight gain are considered to be the most clinically significant adverse events associated with many second-generation antipsychotics.Citation18 As newer agents and formulations become available, differences in weight gain or metabolic side effects are now used as deciding factors when choosing among antipsychotics. In the four acute treatment studies, the paliperidone palmitate group (4%–13%) gained <7% of their baseline bodyweight versus the placebo group (2%–5%).Citation8,Citation10–Citation12 The mean weight increase ranged from +0.4 kg to +1.9 kg on paliperidone palmitate versus −0.3 to −0.7 kg on placebo. In the relapse prevention maintenance study, <7% weight increase occurred in approximately twice as many patients in the paliperidone palmitate group compared to the placebo group (23% versus 12%) at the double-blind endpoint.Citation13 Similarly, in the 52-week open-label extended study, mean (SD) change in weight from baseline to endpoint for the 388 patients was +0.9 (4.3) kg.Citation14 Thus, during shorter treatment duration, the weight gained from paliperidone palmitate is relatively moderate when considering weight gain estimates that have been observed for other oral agents like clozapine and olanzapine. As previously described, the trajectory for increasing weight extends from 6–12 months and even beyond with paliperidone palmitate observations consistent with these prior observations.Citation14 It should also be noted that the weight changes in relapse prevention trials may vastly underreport weight gain as they do not include the stabilization phase prior to randomization. Many subjects at initial stabilization are switched from other antipsychotics that have weight gain that attenuates the degree of weight gain experienced during subsequent treatment as compared to that experienced by antipsychotic naive patients. Nonetheless, the weight gain estimates reported for paliperidone seem to place it in a low to moderate weight gain category relative to other commonly used antipsychotics, although direct comparison studies are needed to substantiate this categorization.

Prolactin levels

Paliperidone palmitate elevates prolactin levels, and the elevation in levels may persist during the maintenance phase due to D2 receptor antagonism.Citation19 Based on the pooled data from the four acute studies, elevated prolactin levels were common in the paliperidone palmitate treatment groups compared to the placebo groups and appeared to be dose-related.Citation8,Citation10–Citation12 Despite prolactin levels being elevated, side effects related to prolactin elevation were not commonly reported. In the three acute studies, side effects related to elevated prolactin levels were seen in ≤2% of the paliperidone palmitate groups versus ≤1% in the placebo groups.Citation8,Citation10,Citation11 The potential prolactin-related adverse events were also low in the fourth acute study: one case in the placebo groups and two cases in the treatment groups.Citation10 In the relapse prevention study, potential prolactin-related adverse events were noted in 2% in the paliperidone palmitate groups and 1% in the placebo groups.Citation13 In this study, mean prolactin levels increased in paliperidone palmitate patients (+12.7 ng/mL in women and +3.7 ng/mL in men), whereas the placebo groups noted a decline in prolactin levels (−16.6 ng/mL in women and −9.2 ng/mL in men). In the 52-week open-label study, 3% of patients were reported to have prolactin-related adverse events and the highest mean prolactin level was seen in the female population.Citation14 The mean (SD) prolactin level changes from baseline for men was +1.6 (13.7) ng/mL and +6.5 (39.4) ng/mL in women. The most common reported events were amenorrhea and galactorrhea.

Injection-site reactions/pain

Injection site pain in the 13-week studies was <8% in paliperidone-treated patients as opposed to <4% treated with placebo injections.Citation8,Citation12 Gluteal injections of paliperidone palmitate were reported to be well tolerated in the 52-week open-label extension study. In this study, injection-site reaction was reported to be “absent” in 82%–87% of the patients.Citation14

Cardiac related – QT prolongation

Paliperidone palmitate “causes a modest increase in the corrected QT (QTc) interval” and it is noted in the product labeling that it should be avoided in combination with drugs that are known to prolong QTc including class 1A or class III antiarrhythmic medications or any other class of medications known to prolong QTc.Citation3 However, in the four acute treatment studies, no QTc interval changes were noted or reported.Citation8,Citation10–Citation12 No patients had a linear derived QTc interval > 480 milliseconds or an increase of >60 milliseconds from baseline during this study. This suggests that conduction abnormalities, as measured by electrocardiography and QTc estimates, are relatively uncommon in healthy patients with schizophrenia who are administered paliperidone palmitate. Given the warnings present in the product labeling, clinicians ought to assess personal or family histories of cardiac conduction abnormalities or other cardiovascular diseases in patients who are candidates for therapy with this drug and formulation.

Dosing and clinical utilization

Paliperidone palmitate is indicated in the United States for the acute and maintenance treatment of schizophrenia in adults. In the literature, paliperidone doses are sometimes expressed as milligram equivalents (mEq) of paliperidone. Therefore, 25, 50, 75, 100, and 150 mEq paliperidone palmitate are equivalent to 39, 78, 117, 156, and 234 mg of paliperidone palmitate, respectively.

For patients who have never taken oral paliperidone or oral/injectable risperidone, tolerability should be established with oral paliperidone or oral risperidone prior to initiating treatment with paliperidone palmitate LAI. Conversions between oral paliperidone and paliperidone palmitate are included in . The recommended initial regimen is a 234 mg injection on day one followed by 156 mg on day eight, each administered into the deltoid muscle. The reason for deltoid administration for the initiation dose is related to the pharmacokinetics of the release profile from this site early in treatment. It is recommended to use a 1-inch 23-gauge needle in patients < 90 kg and 1.5-inch 22-gauge needle in those < 90 kg. Monthly maintenance doses of paliperidone palmitate range from 39–234 mg injected into the deltoid or gluteal muscle. No oral supplementation is required while paliperidone palmitate is being initiated. The day eight dose may be administered ±2 days and monthly doses ±7 days without a clinically significant impact. Paliperidone palmitate can be initiated the day after discontinuing a previous oral antipsychotic agent.Citation3,Citation20 Paliperidone palmitate can be initiated at the next scheduled injection date, and monthly thereafter, in patients switching from other antipsychotic LAI agents.Citation20

Table 3 Doses of oral and injectable paliperidone needed to attain similar concentration at steady-stateCitation14

Paliperidone palmitate has not been extensively studied in patients with renal impairment. Based on pharmacokinetic simulations and a limited number of observations (see earlier information on pharmacokinetic effects), the dose of paliperidone palmitate should be reduced in patients with mild renal impairment. In patients with mild renal impairment (creatinine clearance 50–80 mL/minute), the recommended initial dose is 156 mg on treatment day one and 117 mg a week later. A following monthly injection of 78 mg is recommended. Paliperidone palmitate is not recommended in patients with moderate or severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <50 mL/minute).

No dose adjustment is required in patients with mild or moderate hepatic impairment. At this time, no published data exists regarding its use in severe hepatic impairment.Citation20

The role of LAI antipsychotics in clinical practice

Long-acting antipsychotics such as paliperidone palmitate may be considered for patients requiring maintenance therapy, which includes most patients with schizophrenia. LAIs provide consistent drug delivery that is independent of a patient’s ability or desire to take regularly scheduled oral medications. This minimizes the risk of a patient deliberately or inadvertently taking too much or too little medication and minimizes dosage deviations. In cases where patients fail to receive a scheduled injection, clinicians are able to immediately identify when interruptions in treatment begin. Similarly, in the context of symptom recurrence or exacerbation, examining a patient’s LAI history can assist the clinician in ruling out nonadherence as a possible cause, thereby facilitating more informed decisions about subsequent therapeutic adjustments.Citation21

Many treatment providers mistakenly think that LAIs are undesirable to patients because of the need to get an injection or because of the stigma associated with an injection. In reality, many patients actually prefer the long-acting route, particularly if they are already engaged in treatment.Citation22,Citation23 Furthermore, second-generation LAI antipsychotics, compared to the first-generation LAIs, are likely to have an improved treatment satisfaction and greater acceptance by patients with schizophrenia due to a better tolerability profile.Citation24

In clinical practice, many patients are not presented with an option for long-acting formulations until later in treatment after nonadherence is observed, or they may even be selected as treatment-resistant patients in hopes of overcoming covert nonadherence. When LAIs are viewed as part of a treatment delivery program, as opposed to a direct pharmacologic intervention, they are often received as acceptable and desirable treatment options, even in patients who are receiving treatment during their “first episode.”Citation22

One of the most common challenges encountered in the management of patients with schizophrenia is nonadherence and the recognition and understanding of this phenomenon is important for clinicians as they strategize treatment plans and the potential role for LAI therapies. It is very common for patients to take their medications only intermittently or not at all. Poor and partial adherence to oral antipsychotics has been observed in 35% of patients as early as in the first 4–6 weeks of treatment.Citation21 The rate of nonadherence increases over time and within 2 years of hospital discharge, 75% of patients may be categorized as nonadherent.Citation25 Nonadherence is a multifactorial problem that may result from factors such as greater illness severity (ie, negative symptoms and cognitive deficits), poor patient and caregiver relationship or communication, substance abuse, medication-related side effects, and lack of insight.Citation26 Patients who lack insight into their illness are less likely to be engaged in treatment and are more likely to underestimate the benefits of medication and to discontinue prescribed therapies.Citation27 Inconsistency with medication exacerbates the multiple challenges that are already faced in the management of the patient with schizophrenia. The broader consequences of inadequate treatment further underscore the importance of maintaining treatment. As medication adherence decreases, rates of hospitalization, self-harm, and aggressive behaviors increase.Citation28–Citation31 Addressing barriers to adherence in patients with schizophrenia is challenging as there are a variety of patient-specific reasons that may result in a failure to maintain a consistent pharmacologic treatment regimen.Citation32 Potential barriers to LAI use and benefits of using paliperidone palmitate are presented in .

Table 4 Issues and barriers to long-acting injectable implementation and benefits of using paliperidone palmitate

The selection of a specific LAI antipsychotic for a given patient is a combination of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic factors. When assessing treatment options it may be useful to compare some of the dosing and formulation characteristics of available medications (). One advantage of the LAI formulation of paliperidone palmitate is that it can be used in an acute setting and it can simplify the medication regimen for patients and caregivers ().

Table 5 Comparing the long-acting antipsychotic injections

Patients with schizophrenia often do not conceptualize their symptoms in the same way as their treating clinician.Citation33 Therefore, it is essential for clinicians to carefully assess and consider patient-focused perspectives such as insight into their illness, satisfaction with care, quality of life, and acceptability/understanding of the role of pharmacotherapy, including LAIs. It has been proposed that quality of life assessments should include information on psychosocial, somatic, functional, and social domains, but there is still controversy on how to best measure quality of life.Citation34 Relevant to the role of LAI antipsychotics, a survey of outpatients identified that 87% of patients receiving one of these formulations would choose to continue their injectable medication. Citation35 While some patients prefer injectable medications because they facilitate treatment (ie, it is easier to remember than taking pills daily),Citation36 other patients fear the pain associated with intramuscular injections, consider injections to be intrusive,Citation34,Citation37 or perceive long-acting antipsychotic medications to be a coercive treatment when compared to oral medications.Citation23 Carefully evaluating how patients view or understand the role of pharmacotherapy helps clinicians to build relationships to facilitate positive treatment planning and implementation.

The putative benefit of LAI antipsychotics over oral counterparts is an ongoing debate. Studies comparing paliperidone palmitate to oral paliperidone have not yet been published. In general there appear to be many reports of the benefits of LAI antipsychotics, but also a number of studies showing no added benefit over oral medications. For example, previous published studies evaluating long-term outcome with risperidone LAI versus oral antipsychotic agents did not show differential benefits to risperidone LAI.Citation38–Citation40 Additionally, Gaebel et al published relapse prevention with risperidone LAI versus oral therapy quetiapine, where there appeared to be no difference in relapse between the two treatments although adherence was greater in the risperidone LAI treatment group.Citation41 Outside the context of randomized controlled studies, epidemiological studies and meta-analyses suggest that patients taking LAI antipsychotics have fewer hospitalizations and may be at lower risk for relapse.Citation42,Citation43 The differences in the results of these studies may be due to the nature of the LAI intervention in that it is linked more closely to the type of services provided. This underscores the importance of clinical context and patient-specific factors, which may not be able to be assessed in the structure of randomized controlled studies.

Conclusion

Providing an optimal long-term treatment via choosing the appropriate LAI agent can be challenging. The conventional antipsychotic depot formulations have high propensity to cause EPS. The second-generation antipsychotic paliperidone palmitate has been introduced with a tolerability profile that may be favorable compared to the typical first-generation antipsychotics, and tolerability and efficacy similar to risperidone LAI.Citation44 No comparisons to date have been made between paliperidone palmitate and olanzapine pamoate, another second-generation LAI antipsychotic.

The efficacy of paliperidone palmitate in the acute treatment of schizophrenia has been demonstrated in four short-term trials. However, there are only a few long-term trials assessing maintenance treatment thus far, and the dose-response relationships and strategies for converting from other treatments to paliperidone is an area for additional research. Efficacy appears to be similar to risperidone LAI and the overall tolerability profile seems to be in the mild to moderate range for most antipsychotic-associated side effects, with the exception of prolactin elevation which is very common for paliperidone.

Paliperidone palmitate offers several advantages relative to other available LAI antipsychotics: it can be used as an acute treatment in the outpatient setting, and it has been shown to be well tolerated by patients. Also, it does not require overlapping oral antipsychotic supplementation while it is being initiated, and it offers the convenience of once-monthly administration. The injection volume is small and it offers dosing flexibility. It also gives the patient an option to receive the injection via the deltoid or gluteal route.Citation7 However, one of the challenges of this LAI would be the uncertainties for achieving an optimal dosing regimen based on the clinical data available.

Acknowledgments

Dr Bishop is supported by grant K08MH083888.

Disclosure

Shiyun Kim and Hugo Solari report no conflicts of interest in this work. Dr Weiden has received research/grant support from: NIMH, Ortho-McNeil Janssen, Novartis, Sunovion, Roche/Genetech and is a consultant for Delpor, Genentech, Ortho-McNeil Janssen, and Sunovion. Dr Bishop has received research/grant support from Ortho-McNeil Janssen and is supported by grant K083888 from NIMH.

References

- WeidenPJSolariHKimSBishopJRLong-acting injectable antipsychotics and the management of nonadherencePsychiatr Ann2011415271278

- JunghannsJMullerRNanocrystal technology, drug delivery and clinical applicationsInt J Nanomedicine20083329530918990939

- Once-monthly Invega® Sustenna™ (paliperidone palmitate) extended-release injectable suspension [package insert]Titusville, NJJanssen Pharmaceuticals2011

- SamtaniMNVermeulenAStuyckensKPopulation pharmacokinetics of intramuscular paliperidone palmitate in patients with schizophrenia: a novel once-monthly long-acting formulation of an atypical antipsychoticClin Pharmacokinet200948958560019725593

- VermeirMNaessensIRemmerieBAbsorption, metabolism, and excretion of paliperidone, a new monoaminergic antagonist, in humansDrug Metab Dispos200836476977918227146

- Invega® paliperidone extended-release tablets [package insert]Titusville, NJJanssen Pharmaceuticals2006

- HoughDLindenmayerJPGopalSSafety and tolerability of deltoid and gluteal injections of paliperidone palmitate in schizophreniaProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry20093361022103119481579

- GopalSHoughDWXuHEfficacy and safety of paliperidone palmitate in adult patients with acutely symptomatic schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response studyInt Clin Psychopharmacol201025524725620389255

- ShayeganDKStahlSMAtypical antipsychotics: matching receptor profile to individual patient’s clinical profileCNS Spectr2004910 Suppl 1161415475871

- KramerMLitmanRHoughDPaliperidone palmitate, a potential long-acting treatment for patients with schizophrenia. Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety studyInt J Neuropsychopharmacol201013563564719941696

- NasrallahHAGopalSGassmann-MayerCA controlled, evidence-based trial of paliperidone palmitate, a long-acting injectable antipsychotic, in schizophreniaNeuropsychopharmacology201035102072208220555312

- PandinaGJLindenmayerJPLullJA randomized, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and safety of three doses of paliperidone palmitate in adults with acutely exacerbated schizophreniaJ Clin Psychopharmacol201030323524420473057

- HoughDGopalSVijapurkarULimPMorozovaMEerdekensMPaliperidone palmitate maintenance treatment in delaying the time-to-relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studySchizophr Res20101162–310711719959339

- GopalSVijapurkarULimPMorozovaMEerdekensMHoughDA 52-week open-label study of the safety and tolerability of paliperidone palmitate in patients with schizophreniaJ Psychopharmacol201125568569720615933

- FleischhackerWWGopalSLaneRA randomized trial of paliperidone palmitate and risperidone long-acting injectable in schizophreniaInt J Neuropsychopharmacol7222011 [Epub ahead of print.]

- PandinaGLaneRGopalSA double-blind study of paliperidone palmitate and risperidone long-acting injection in adults with schizophreniaProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry201135121822621092748

- LiHRuiQNingXXuHGuNA comparative study of paliperidone palmitate and risperidone long-acting injectable therapy in schizophreniaProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry20113541002100821315787

- KroezeWKHufeisenSJPopadakBAH1-histamine receptor affinity predicts short-term weight gain for typical and atypical antipsychotic drugsNeuropsychopharmacology200328351952612629531

- SchotteAJanssenPFGommerenWRisperidone compared with new and reference antipsychotic drugs: in vitro and in vivo receptor bindingPsychopharmacology (Berl)19961241–257738935801

- GopalSGassmann-MayerCPalumboJSamtaniMNShiwachRAlphsLPractical guidance for dosing and switching paliperidone palmitate treatment in patients with schizophreniaCurr Med Res Opin201026237738720001492

- NasrallahHAThe case for long-acting antipsychotic agents in the post-CATIE eraActa Psychiatr Scand2007115426026717355516

- WeidenPJSchoolerNRWeedonJCElmouchtariASunakawaAGoldfingerSMA randomized controlled trial of long-acting injectable risperidone vs continuation on oral atypical antipsychotics for first-episode schizophrenia patients: initial adherence outcomeJ Clin Psychiatry200970101397140619906343

- PatelMXde ZoysaNBernadtMBindmanJDavidASAre depot antipsychotics more coercive than tablets? The patient’s perspectiveJ Psychopharmacol201024101483148919304865

- FleischhackerWWSecond-generation antipsychotic long-acting injections: systematic reviewBr J Psychiatry Suppl200952S29S3619880914

- WeidenPJRapkinBZygmuntAMottTGoldmanDFrancesAPostdischarge medication compliance of inpatients converted from an oral to a depot neuroleptic regimenPsychiatr Serv19954610104910548829787

- LoveRCStrategies for increasing treatment compliance: the role of long- acting antipsychoticsAm J Health Syst Pharm20025922 Suppl 8S10S1512455294

- HeinrichsDWCohenBPCarpenterWTJrEarly insight and the management of schizophrenic decompensationJ Nerv Ment Dis198517331331382857763

- WeidenPJKozmaCGroggALocklearJPartial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophreniaPsychiatr Serv200455888689115292538

- Alia-KleinNO’RourkeTMGoldsteinRZMalaspinaDInsight into illness and adherence to psychotropic medications are separately associated with violence severity in a forensic sampleAggress Behav2007331869617441009

- HeringsRMErkensJAIncreased suicide attempt rate among patients interrupting use of atypical antipsychoticsPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf200312542342412899119

- VelliganDIWeidenPJSajatovicMThe expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illnessJ Clin Psychiatry200970Suppl 414619686636

- WeidenPJUnderstanding and addressing adherence issues in schizophrenia: from theory to practiceJ Clin Psychiatry200768Suppl 141419

- LarsenEBGerlachJSubjective experience of treatment, side-effects, mental state and quality of life in chronic schizophrenic out-patients treated with depot neurolepticsActa Psychiatr Scand19969353813888792909

- KaneJMAgugliaEAltamuraACGuidelines for depot antipsychotic treatment. European Neuropshychopharmacology Consensus Conference in Siena, ItalyEur Neuropsychopharmacol19988155669452941

- PereiraSPintoRA survey of the attitudes of chronic psychiatric patients living in the community toward their medicationActa Psychiatr Scand19979564644689242840

- WistedtBHow does the psychiatric patient feel about depot treatment, compulsion or help?Nord J Psychiatry199549Suppl 354146

- GlazerWMKaneJMDepot neuroleptic therapy: an underutilized treatment optionJ Clin Psychiatry199253124264331362569

- ChuePEerdekensMAugustynsIComparative efficacy and safety of long-acting risperidone and risperidone oral tabletsEur Neuropsychopharmacol200515111111715572280

- MacfaddenWMaYWHaskinsJTBossieCAAlphsLA prospective study comparing the long-term effectiveness of injectable risperidone long-acting therapy and oral aripiprazole in patients with schizophreniaPsychiatry (Edgmont)2010711233121191530

- RosenheckRAKrystalJHLewRRisperidone and oral antipsychotics in unstable schizophreniaN Engl J Med2011364984285121366475

- GaebelWSchreinerABergmansPRelapse prevention in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder with risperidone long-acting injectable vs quetiapine: results of a long-term, open-label, randomized clinical trialNeuropsychopharmacology201035122367237720686456

- SchoolerNRRelapse and rehospitalization: comparing oral and depot antipsychoticsJ Clin Psychiatry200364Suppl 16141714680414

- TiihonenJHaukkaJTaylorMHaddadPMPatelMXKorhonenPA nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after f irst hospitalization for schizophreniaAm J Psychiatry2011168660360921362741

- NasrallahHAAtypical antipsychotic-induced metabolic side effects: insights from receptor-binding profilesMol Psychiatry2008131273517848919

- RichelsonESouderTBinding of antipsychotic drugs to human brain receptors focus on newer generation compoundsLife Sci2000681293911132243

- Zyprexa Relprevv® (olanzapine) for extended release injectable suspension [package insert]Indianapolis, INEli Lilly and Company2010

- Risperdal Consta® (risperdone) long-acting injection [package insert]Titusville, NJJanssen Pharmaceuticals2011

- Haloperidol decanoate injection [package insert]Irvine, CATeva Parenteral Medicines2009

- Fluphenazine decanoate injection [package insert]Bedford, OHBedford Laboratories2010