Abstract

Background

Lack of adherence with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy is the major cause of treatment failure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. We evaluated the effectiveness of our intensive educational program on adherence in the short term and the long term.

Methods

The educational program consisted of: intensive training, whereby each patient performed individual and collective sessions of three hours receiving information about obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, familiarizing themselves with CPAP tools, on six consecutive days; long-term training; and support meetings, with reassessment at three months and one year.

Results

In 202 patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, the mean (standard deviation) apnea/hypopnea index was 45 ± 22, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale score was 14 ± 5, and the average titration pressure was 10 ± 2 cm H2O. At three months, 166 patients (82%) used CPAP for an average of 7.3 hours per night. At one year, 162 (80%) used CPAP for about seven hours per night. At two years, 92 patients (43%) used CPAP for about five hours per night. The level of satisfaction remained higher in patients in ventilation.

Conclusion

Our data show strong adherence to CPAP at three months and one year, with a decrease at two years. The initial educational program seems to play an important role in adherence. This effect is lost in the long term, suggesting that periodic reinforcement of educational support would be helpful.

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome is a disorder characterized by repeated interruption of breathingCitation1 due to obstruction of the upper airway.Citation2 The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome is 4%–5% in the general population, and is associated with increased cardiovascular risk,Citation3 increased risk of car accidents,Citation4 and increased use of health care resources.Citation5 Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome reduces daytime sleepiness,Citation6 improves cognitive function,Citation7 and reduces sympathetic neural activation, blood pressure,Citation8 and mortality.Citation9 These results are related to proper adherence with treatment.Citation10 Side effects, such as claustrophobia, difficulty in using the machine, and psychological or psychosocial factors, can affect night-time ventilator use.Citation11

Predictors of adherence to night-time CPAP treatment for obstructive sleep apnea are still lacking.Citation12 Suspension of CPAP use restores symptoms and the risks of obstructive sleep apnea at critical levels.Citation13 It is estimated that between 29% and 83% of patients are not adherent with CPAP ventilation. The most recent definition of CPAP adherence is ventilator use for at least four hours per night on at least 70% of nights, and for at least 30 days in the first three months after prescription.Citation14 It is stressed that the main problem with treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome is poor adherence to CPAP in the short term, and even more so in the long term.Citation15

Various methods have been proposed to increase compliance, such as achieving the proper titration, using the most appropriate ventilator, eg, auto-CPAP, auto-BiPAP (bilevel positive airway pressure), proper humidification of the upper airways, and educational and psychological programs.Citation11 These interventions are based on theoretical models, and their aim is to remove all barriers that the patient perceives in using CPAP. This suggests the need for an educational program, as recommended in the literature,Citation16–Citation18 with structured models developed in hospital.

The role of education in improving CPAP use in the long term has only received modest attention until now. Likar and al showed that therapeutic education of two hours every six months increases CPAP use by at least one hour per night in more than 90% of patients.Citation19 In this study, we assessed the educational effectiveness of an educational protocol for adherence to CPAP at three months and one year after titration, and its effect was still present at two years. Our educational program comprised two stages, ie, initial “intensive” training and a subsequent “periodic” follow-up approach.

Methods

Two hundred and two patients diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea were recruited consecutively from the Pulmonary Rehabilitation Unit at Rivolta d’Adda Hospital from January 1, 2004 to May 31, 2008. Inclusion criteria were age 25–85 years, a new polysomnographic diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea, and not having received previous treatment with noninvasive mechanical ventilation. The severity of obstructive sleep apnea was assessed by the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI, ie, the number of apneas and hypopneas per hour).

Apneas and hypopneas were analyzed according to the guidelines of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force,Citation20 with apnea defined as absence of air flow for at least 10 seconds and hypopnea as a reduction in air flow of at least 30% associated with desaturation of 4%. An AHI of at least 15 events per hour was considered the lower limit for enrolment. The anthropometric characteristics and baseline measures of disease severity for the study population are shown in .

Table 1 Baseline characteristics and anthropometric measures of disease severity in the study population

All patients underwent an adaptive training program in two steps, comprising “intensive” adaptive training for three hours on six consecutive days after CPAP titration, using an individually tailored technical and practical approach,Citation21 followed by periodic follow-up in a group setting to reinforce the concepts and treatment techniques relevant to obstructive sleep apnea.Citation21 The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee.

During the six days of intensive training, each patient underwent both individual and group training. The follow-up support program provided for an ambulatory meeting at three months and one year. At three months, one year, and two years, hours of adherence and degree of satisfaction were evaluated on a subjective three-level scale (poor, enough, good) by each patient. Hours of CPAP adherence were assessed by the memory card in the home ventilator. Adherence to CPAP treatment was defined as a minimal acceptable duration of use of at least four hours per night on >70% of nights monitored. Subjects who spontaneously suspended CPAP or were absent from the scheduled control checks, were considered to be nonadherent.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study population. Statistical analysis was performed using the Stat View software package (StatView, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). A nonparametric method Mann–Whitney test was performed. A P value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Intensive adaptive training

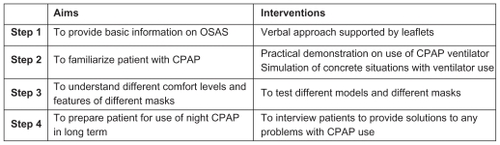

The following steps were performed strictly according to the order stated and were repeated several times depending on the patient’s subjective response (see ).

Figure 1 Intensive training.

Step 1

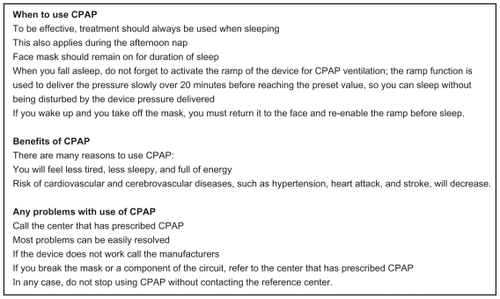

The aim of the first step was to provide basic information on obstructive sleep apnea, focusing on a proper knowledge of the etiology of sleep apnea, how it occurs, what causes it, the health risks involved if it is left untreated, and the treatments available, in order to improve patient awareness for the illness. A verbal approach was taken, based on a brochure () given to patients, in which the use of CPAP use was explained.

Step 2

The aims of the second step were to enable the patient to become familiar with the equipment used for home CPAP, to improve awareness of the CPAP circuitry and of each accessory (whisper, tubing, filters), and to provide a modality of maintenance and regular cleaning of the machine, with a telephone number to call in the event of machine failure. This was achieved by practical demonstration and simulation of ventilator use, and of the alarm and humidification systems ().

Step 3

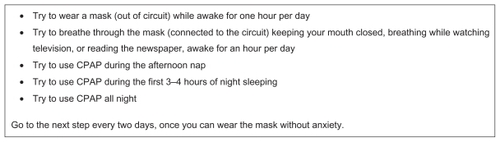

The purpose of the third step was to introduce the features and comfort of the different nasal masks and caps, and to provide solutions to problems with nasal masks, in particular the possible impact of claustrophobia. This step involved performing tests with different models and different masks.

Step 4

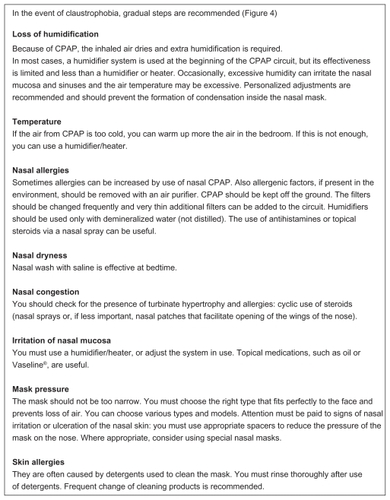

The final step was to prepare the patient for use of CPAP in the long term and to provide solutions to problems with the home ventilator (). This step comprised a question and answer session, directed to build trust and collaboration in the patient/caregiver relationship.

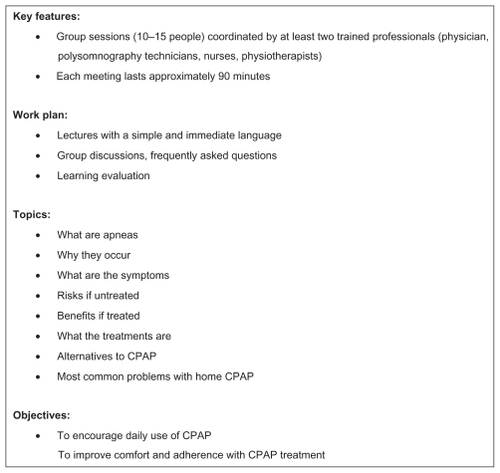

Long-term support program

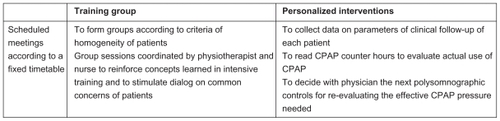

The long-term support program ( and ) was based on educational criteria, and had the following components:

Figure 6 Educational program for home CPAP therapy in the long term.

Coordination of training groups according to homogeneity of patients

Issuing of subsequent clinical appointments

Chaired group sessions with frontal teaching, coordinated by professional figures (neurophysiopathology technician, physiotherapist, and nurse), strengthening concepts and behaviors learned in intensive training, and to encourage interindividual comparisons of common issues for patients

Collection of data for clinical follow-up on: body mass index for evaluation of weight loss; Epworth Sleepiness Scale score for evaluation of daytime sleepiness; and actual CPAP use assessed using the CPAP counter

Establishing a control polysomnographic pressure with the physician to enable re-evaluation of any new effective CPAP titration.

Results

All 202 patients with obstructive sleep apnea enrolled in this study completed their intensive adaptive training and started CPAP home ventilation. The main anthropometric characteristics and polysomnographic data for the study population are summarized in . The patients comprised 159 males and 43 females, with a mean age of 57 ± 12 years, body mass index of 36 ± 8, AHI of 45 ± 22 events per hour, and an Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of 14 ± 5. Three months after the beginning of ventilation (average pressure 10 ± 2 cm H2O), CPAP adherence was 82%. Ten patients decided to terminate CPAP treatment (in this group basal Epworth Sleepiness Scale was 12 ± 3) and 26 were lost to follow-up. Adherence to CPAP was 80% one year after the long-term support program. Four patients decided to terminate CPAP treatment. Two years after the start of treatment and at one year since the last session of the support program, long-term adherence to ventilation was 43%. Seventy-eight patients decided to terminate CPAP treatment (in this group basal Epworth Sleepiness Scale was 14 ± 4) and 32 were lost to follow-up. The average hours of CPAP use at three months were 7.3 hours per night, seven hours per night at one year, and five hours per night at two years. Daytime sleepiness measured by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale was 6 ± 4 at three months and 5 ± 4 at one and two years. The degree of patient satisfaction was reported as follows: 60% of patients felt very satisfied with CPAP, 32% were sufficiently satisfied, and 8% were poorly satisfied at three months. At one year, 65% of patients felt very satisfied, 28% were sufficiently satisfied, and 7% were poorly satisfied. At two years, 49% of patients felt very satisfied, 3% were sufficiently satisfied, and 48% were poorly satisfied. To assess the causes of noncompliance with ventilation, we evaluated the difference between basic sleepiness measured by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale and basal AHI in subjects who spontaneously suspended CPAP and patients who had continued the treatment. We did not find any statistically significant difference between the two groups.

Discussion

We investigated the effectiveness and importance of an educational protocol on adherence to CPAP in the short term (three months) and long term (one and two years) after the beginning of night ventilation. Our data seem to show the effectiveness of our educational protocol on appropriate adherence to ventilation at three months and one year of CPAP treatment. This result seems to be linked to the educational program performed in intensive mode during hospitalization and to the long-term support program at three months and one year after discharge from hospital. At two years, one year after suspension of our program, adherence to CPAP was reduced in our patients.

The aim of this study was to test a method of organizing and applying educational support for long-term night ventilation in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, in order to verify if a more efficient and reliable follow-up system could prolong CPAP use. One of the potential criticisms of this study is that it is a methodological protocol to increase CPAP compliance in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome patients, therefore does not take into consideration reasons why patients stopped using CPAP or psychological variables to enhance CPAP compliance.

Various types of CPAP machines are available, and can monitor the effectiveness of treatment, losses from the mask, persistence of snoring, and residual apneas/hypopneas. These models call our attention to recognizing these parameters and correcting them if possible. This supporting system seems to be closely linked to the success of adherence with ventilation.Citation22 Intervention cannot be based only on solving technical problems, but must be related to socioeconomic and psychological factors, which may affect the ability of the patient to manage his/her health problems and are closely linked with daily use of CPAP.Citation23,Citation24

CPAP therapy shows its effectiveness for most patients, but its costs are high. According to this discussion, more restrictive criteria in the US are required for reimbursement of CPAP, such as demonstrated adherence with ventilation.Citation14

The definition of adherence with minimum ventilation on a nightly basis is an even more complex issue. Several studies have demonstrated a need for daily use of CPAP for at least 4–6 hours per night to have an improvement in symptoms and daytime sleepiness.Citation25 It is still rather unclear how many hours of night use are needed to reduce cardiovascular risk. Campos-Rodriguez et alCitation26 have shown that those patients who use CPAP for at least 2–5 hours every night have a reduced risk of mortality and morbidity compared with those who use it one hour per night.

Intensive adaptive training appeared to provide good adherence in the short term (three months), reaching compliance levels in excess of 80%, associated with an average use of more than seven hours per night and with high levels of subjective satisfaction reported by patients. These results seem to coincide with the literature. Budhiraja et alCitation3 have shown that the first 3–7 days of treatment are closely linked with the subsequent use of the CPAP ventilator after 30 days.

McArdle et alCitation27 reported that 68% of patients continued treatment at five years. In fact, long-term compliance with night ventilation is unlikely and is linked to the support system of the center. Therefore, our long-term support program, running for three months and one year, could achieve good compliance, even over a long period, with 80% adherence and daily use of the ventilator for at least seven hours per night at one year. Without our educational support program, we could see a sharp drop in adherence during the second year. The initial experience and educational reinforcement seemed to play an important role on early adherence to ventilation, but this effect seems to be lost in the long term, suggesting the need to continue the motivational support.

It must be stressed that our program was designed mainly for a rehabilitation facility, but its intent was to open up discussion with all the organizations that deal with cardio-respiratory sleep disorders. In an increasingly cost-conscious environment, costs can be minimized by training of specialized teams to manage groups of patients with whom they stay in contact also by periodic telephone calls. We are aware that our study has some limitations. We considered a mainly male population referred to a single medical center. It was not possible to identify reasons why some patients had abandoned the program. The study population presented with moderate to severe AHI during sleep and, it is known that the severity of the apneic framework is one of the factors affecting compliance with ventilation. Importantly, this was a retrospective study and did not include a control group in the protocol.

Acknowledgment

The authors appreciate the language support provided by Dr Sabrina Dal Pra.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SullivanCEIssaFGObstructive sleep apneaClin Chest Med1985646336503936665

- HudgelDWVariable site of airway narrowing among OSAS patientsJ Applied Physiol198661414021409

- BudhirajaRQuanSFSleep-disordered breathing and cardiovasular healthCurr Opin Pulm Med200511650150616217175

- BarbeFPericasJMunozAAutomobile accidents in patients with sleep apnea syndrome. An epidemiological and mechanicistic studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med1998158118229655701

- KapurVKRedlineSNietoFJThe relationship between chronically disrupted sleep and healthcare useSleep200225328929612003159

- MunozAMayoralasLRBarbeFLong-term effects of CPAP on daytime functioning in patients with sleep apnoea syndromeEur Respir J200015467668110780758

- EnglemanHMMartinSEDearyIJEffect of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on daytime function in sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndromeLancet199434388975725757906330

- PapperellJCRamdassingh-DowSCosthwaiteNAmbulatory blood pressure after therapeutic and subtherapeutic nasal continuous positive air way pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea: a randomised parallel trialLancet2002359930220421011812555

- MartiSSampolGMunozXMortality in severe sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome patients: impact of treatmentEur Respir J20022061511151812503712

- EnglemanHMkingshottRNWraithPKRandomized placebo-controlled crossover trial of continuous positive air way pressure for mild sleep apnoea/hypopnea syndromeAm J Respir Crit Care Med199915924614679927358

- SmithINadingVLassersonTJEducational, supportive and behavioral interventions to improve usage of continuous positive airway pressure machines for adults with obstructive sleep apnoeaChocrane Database Syst Rev20092CD007736

- MeuriceJCDorePPaquerauJPredictive factors of long-term compliance with nasal continuous positive airway pressure treatment in sleep apnea syndromeChest199410524294338306741

- KribbsNBPackAlKlineLREffects of one night without nasal CPAP treatment on sleep and sleepiness in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndromeAm Rev Respir Dis19931475116211688484626

- AloiaSKnoepkeCLee-ChiongTThe new local coverage determination criteria for adherence to positive airway pressure treatment: testing the limits?Chest2010138487587920348198

- PietersTHCollardPHAubertGDuryMDelgustePRodensteinDOAcceptance and long term compliance with nCPAP in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndromeEur Respir J1996959399448793455

- ChervinRDTheutSBassettiCAldrichMSCompliance with nasal CPAP can be improved by simple interventionsSleep19972042842899231954

- FletcherFCLuckettRAThe effect of positive reinforcement on hourly compliance in nasal continuous positive airway pressure users with obstructive sleep apneaAm Rev Respir Dis19911435 Pt 19369412024846

- ChervinRDTheuSBassettiCAldrichMSInterventions to improve compliance with nasal CPAPSleep Res199625220226

- LikarLLPancieraTMEricksonADRountsSGroup education sessions and compliance with nasal CPAP therapyChest19971115127312779149582

- [No authors listed]Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement technique in clinical research The report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task ForceSleep199922566768910450601

- RotaMZibettiSPirolaAPatrunoVAiolfiSAdherence to CPAP treatment in patients with obstructive apnea during sleep. The role of respiratory rehabilitation therapistARIR20011012024

- WeaverTEKribbsNBPackAINight-to-night variability in CPAP use over first three month of treatmentSleep19972042782839231953

- PlattABFieldSHAschDANeighborhood of residence is associated with daily adherence to CPAP therapySleep200932679980619544757

- Simon-TuvalTReuveniHGreenberg-DotanSLow socioeconomic status is a risk factor for CPAP adherence among adult OSAS patients requiring treatmentSleep200932454555219413149

- BennettSLBarbourCLangfordBHealth status in obstructive sleep apnea. Relation with sleep fragmentation and daytime sleepiness, and effects of continuous positive airway pressure treatmentAm J Respir Crit Care Med199915961884189010351935

- Campos-RodriguezFPerez-RonchelJGrilo-ReinaALima-AlvarezJBeneitezMAAlmeida-GonzalezCLong-term effect of continuous positive airway pressure on BP in patients with hypertension and sleep apneaChest200713261847185217925415

- McArdleNDevereuxGHeidarnejadHLong-term use of CPAP therapy for sleep apnea/hypopnea syndromeAm J Respir Crit Care Med19991594 Pt 11108111410194153