Abstract

Objective

To clarify the mechanisms of adherence.

Methods

A cross-sectional, multicenter French study using a self-questionnaire administered by 116 general practitioners to 782 obese type 2 diabetic patients.

Results

The analysis of 670 completed questionnaires revealed a strong association between the adherence to medication and the behavior of fastening the seatbelt when seated in the rear of a car. Multivariate analysis indicated that this behavior was an independent determinant of adherence to medication (odds ratio [OR] 2.3, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.4–3.6, P < 0.001) with the same OR as the motivation to adhere to medical prescriptions (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.3–3.6, P = 0.003) in a model with good accuracy (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve 0.774). A multiple correspondence analysis suggested that adherence to medication and seatbelt behavior are “homologous” behaviors, with homology between phenomena defined by the fact that they share a common etiology.

Conclusion

Adherence may have two dimensions: passive (obedience, the main determinant of seatbelt behavior) and active (motivation). This conclusion has theoretical and practical implications. Firstly, empowerment through patient education can be defined as a process that replaces the passive mechanism of adherence in patients’ minds with an active, conscious choice. Secondly, recognizing these two dimensions may help to establish a tailored patient-physician relationship to prevent nonadherence.

Introduction

Adherence to long-term therapies is an important issue in contemporary medicine. Low adherence to prescribed treatments is very common. Typical adherence rates for prescribed medications are about 50%, with a range from 0% to over 100%.Citation1 Specifically, for diabetes, there is an inverse relationship between adherence to medication and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).Citation2,Citation3 A multivariate analysis has indicated that nonadherence is significantly associated with increased risks for all-cause hospitalization and all-cause mortality.Citation4 Adherence to a diabetes therapy has been found to be associated with a decrease in healthcare costs, mostly through a decrease in hospitalization.Citation5,Citation6 More generally, a World Health Organization report concluded that increasing the effectiveness of adherence interventions may have a far greater impact on the health of the population than any improvement in specific medical treatments.Citation7

Several studies suggest that adherence and nonadherence are general behaviors. For instance, adherers to medication are often compliant with other tasks related to their treatment: adherence to bisphosphonates can be predicted by adherence to another medication, for instance, a statin.Citation8 Two studies have shown that adherence to bisphosphonates or statins is associated with the use of preventive health services, such as prostate-specific antigen tests, fecal occult blood tests, screening mammography, and influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations.Citation8,Citation9 Furthermore, nonsmokers accept a complex treatment more easilyCitation10 and are more adherent to bisphosphonate therapy.Citation8 By contrast, diabetic patients who smoke are less adherent to recommendations concerning blood-glucose monitoring and exercise and skip more medical appointments than nonsmokers.Citation11 Similarly, alcohol consumption is a marker of poorer adherence to diabetes self-care behavior.Citation12 Berrigan et al, investigating the adherence to recommendations for five health behaviors (physical activity, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, fruit and vegetable consumption, and dietary fat intake), observed that the two extreme patterns, all adherence and all nonadherence, were found in approximately twice the expected proportions.Citation13

This study aimed to clarify the mechanisms of adherence to medication. Obese adult type 2 diabetic patients were asked, via their general practitioner (GP), to complete a self-questionnaire assessing adherence to medication and to answer questions addressing their health, their medications, and their motivation to improve their weight, blood pressure, or diabetes control. Specifically, the hypothesis that adherence to medication may reflect an even more general human behavior was tested. Thus, a question on an apparently distinct behavior was included, asking the patients whether they fastened their seatbelt when they were seated in the rear of a car.

Methods

This cross-sectional, multicenter French study included 116 GPs and 782 patients who agreed to participate. Diabetic patients treated with a single antidiabetic oral agent, older than 18 years, with an HbA1c level ≥6.5%, body mass index ≥30 kg/m2, abdominal obesity according to standard criteria, and who were able to understand the recommendations were eligible to participate in the study. Pregnant women, patients with a severe disease, or those participating in another study were excluded. The participants lived in all regions of the country, both rural (9% were farmers) and urban. Each GP provided between one and 11 evaluable questionnaires (median 6.5, quartiles Q1,Q3: 3,9). Before completing the questionnaire, the patients were given a letter informing them that they could voluntarily participate in a research program with the goal of exploring the determinants of adherence to medical recommendations. The questionnaires from 670 patients (85.7%) were considered suitable for evaluation.

The full questionnaire is shown in . It included the following questions: (i) nine general questions, such as “Do you think that your health is important?” (possible answers: In no way, A little bit, Rather, A lot), “Does the opinion of your family count?” (possible answers: In no way, A little bit, Rather, A lot), “Generally speaking, what do you give priority to?” (possible answers: To the present, To the future), “Are you used to fastening your seatbelt when you sit in the rear of a car?” (possible answers: No, Yes); (ii) a six-item medication adherence questionnaire,Citation14 validated in the field of hypertension, that classified patients as nonadherers if they answered positively to at least two questions, such as “This morning, did you forget to take your medication?” (possible answers: No, Yes); (iii) 17 questions on diabetes control, blood pressure, and weight, such as “Are you satisfied with the control of your blood pressure?” (possible answers: In no way, A little bit, Rather, Completely) and “Would you be ready to make efforts to improve your weight?” (possible answers: In no way, A little bit, Rather, A lot); (iv) three questions on the motivation to follow the recommendations of the physician concerning prescribed medication, physical activity, and dietary advice, such as “Are you motivated to follow the recommendations of your physician with regard to the prescribed medication?” (possible answers: Not motivated, Little motivated, Motivated enough, Very motivated); and (v) one question, “What are the main reasons that motivate you to follow the recommendations of your physician?” for which five answers (for instance, the chance to live longer) were proposed.

Appendix I The questionnaire

For questions with four possible answers, data were dichotomized by pooling the two negative answers and the two positive answers. For the three questions concerning motivations for medication, exercise, and diet, patients were considered to be “motivated” if they stated that they were “motivated enough” or “very motivated” and they were considered “not motivated” if they stated that they were “not motivated” or “little motivated” to at least one of the three questions. Patients’ HbA1c levels and body mass indexes were obtained from their GPs.

SAS 8.2 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used for the statistical analysis. For continuous data, the mean, standard deviation, quartiles Q1 and Q3, and median value were calculated. For categorical data, the frequency and percentage of the class level were calculated. Univariate comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test for continuous data, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for ordinal categorical data, and the chi-square test for nonordinal categorical data. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine the independent predictors of adherence to medication. A multiple correspondence analysis of the data was also performed. The research protocol was approved by the University Ethics Review Board.

Results

The median age of the patients was 60 years (range 21–89 years, Q1,Q3: 53,66); 53.7% were female, 41% were retired, 12.4% were current smokers, 65.3% had hypertension, and 61.6% had hypercholesterolemia. The median body mass index was 34.1 (Q1,Q3: 31.6,37.6), and the median HbA1c was 7.0% (Q1,Q3: 6.7,7.7).

As shown in , 20.1% of the patients were classified as nonadherers in the adherence questionnaire. This percentage was more than twice as high in patients who declared that they did not fasten their seatbelt compared with those who did (31.5% versus 14.5%, P < 0.001). In total, 32.2% of the patients declared that they did not usually fasten their seatbelt. This percentage was twice as high for nonadherers compared with adherers (51.1% versus 27.5%, P < 0.001). Furthermore, nonadherers more frequently had an uncontrolled HbA1c level (>7%) than adherers (74.2% versus 54.3%, P < 0.001). The same was true when comparing seatbelt nonfasteners with fasteners (64.8% versus 55.0%, P = 0.016).

Table 1 Questions with significantly different answer distributions between adherers and nonadherers

shows items of the questionnaire with statistically different distributions of answers when patients were classified as nonadherers or adherers. Statistical differences were exactly the same when the patients were classified as seatbelt nonfasteners or fasteners.

In a multivariate analysis, the following determinants remained associated with adherence to medication: HbA1c ≤7% (odds ratio [OR] 2.7, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.6–4.5, P < 0.001), fastening the seatbelt (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.4–3.6, P < 0.001), motivated concerning health (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.3–3.6, P = 0.003), ready to make efforts to improve diabetes (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.2–3.4, P = 0.005), declaring that it is good to follow medical prescriptions (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2–3.0, P = 0.012), and knowledge of one’s HbA1c level (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.1–2.8, P = 0.016). The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve describing this model was 0.774.

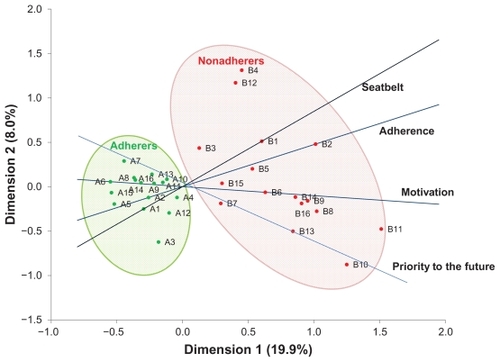

A multiple correspondence analysis of the answers shown in was then performed (). The dots appear to distinguish two nonoverlapping clusters of answers defining adherent and nonadherent behavior. This figure presents four axes, linking the answers to the questions on adherence, seatbelt behavior, motivation, and priority given to the future. The figure confirms the closeness between the “adherence” and “seatbelt” axes, indicating that these behaviors had similar relationships to the patients’ other answers, as shown in .

Figure 1 Multiple correspondence analysis. A1, seatbelt fasteners; B1, seatbelt nonfasteners; A2, adherers; B2, nonadherers; A3, HbA1c ≤ 7%; B3, HbA1c > 7%; A4, nonsmoker; B4, ex-smoker/current smoker; A5, follows weight on a regular basis; B5, does not follow weight; A6, motivated; B6, not motivated; A7, priority to the future: yes; B7, priority to the future: no; A8, ready to make efforts to improve diabetes control; B8, not ready to make efforts to improve diabetes control; A9, recommendations are too strict: disagree; B9, recommendations are too strict: agree; A10, not interested in changing lifestyle: disagree; B10, not interested in changing lifestyle: agree; A11, not a priority: disagree; B11, not a priority: agree; A12, have no time: disagree; B12, have no time: agree; A13, your health depends on you: agree; B13, your health depends on you: disagree; A14, your health is very important: agree; B14, your health is very important: disagree; A15, the opinion of your family is very important: agree; B15, the opinion of your family is very important: disagree; A16, following doctor’s recommendations is very good: agree; B16, following doctor’s recommendations is very good: disagree.

Discussion

In this study, an unexpected strong association was observed between the adherence to medication and seatbelt fastening when seated in the rear of a car: fastening the seatbelt was found to be a highly significant determinant (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.4–3.6, P < 0.001) of adherence to medication by multivariate analysis in a model with good accuracy (area under the ROC curve 0.774), with the same OR as the motivation to adhere to medical prescriptions (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.3–3.6, P = 0.003). Furthermore, the same pattern of answers to questions on feelings concerning health and treatment and recommendations provided by the GPs was observed when patients were classified as adherers or nonadherers and as seatbelt fasteners or nonfasteners. This striking similarity between apparently distinct behaviors, illustrated by the closeness of the adherence and seatbelt axes in the multiple correspondence analysis (), suggests that the adherence to medication, on the one hand, and the fastening of the seatbelt in the rear of a car, on the other, represent “homologous” (not only analogous) behaviors, with homology between the phenomena defined by the fact that they share a common etiology, as explained by Wise and Bozarth:Citation15

“In biology, there are examples of superficially similar behaviors or organs that have evolved independently for these “analogous” behaviors or organs look similar, but one cannot draw further conclusion from their similarity. In each case, the analogous details are striking, but there is no commonality of origin, and thus no necessary commonality of mechanism. By contrast, “homologous” organs or behaviors derive from common ancestral origin and, in biology, from common embryonic tissue, whereas analogies do not. Here knowledge of one of a set of homologous organs or behaviors almost necessarily has some degree of heuristic value for the study of the others, even if the organs or behaviors are superficially dissimilar.” (Copyright © 1987 by the American Psychological Association. Reproduced with permission.)

In other words, discovering a homology between phenomena has a heuristic value because, as stated by Elster,Citation16 in the case of homologous phenomena, their definition becomes ipso facto inseparable from their explanation.

Thus, understanding why people fasten their seatbelt in the rear of a car may present a clue to the mental mechanisms behind adherence to medication. LanglieCitation17 and Williams and WechslerCitation18 observed an association between seatbelt use and the practices of medical check-ups, dental care, immunizations, miscellaneous medical examinations, exercise, and diet. Here, seatbelt use was seen as another health behavior intended to indirectly protect physical well-being.Citation17 However, seatbelt behavior may have another meaning. A recent study in Malaysia investigated various factors associated with the behavior of not wearing a rear seatbelt. The experience of being stopped by an enforcement officer yielded the highest OR, followed by factors such as self-consciousness, attitude, knowledge, age, and the perception of being caught by an enforcement officer.Citation19 Another study in the Midwest United StatesCitation20 showed that drivers from secondary seatbelt legislation states, where drivers are ticketed only when there is another citable traffic offense, wore their seatbelts significantly less often. This finding reinforces the idea that obedience to the law is the primary cause of this behavior rather than the real wish to protect oneself. On the contrary, some people may refuse to fasten their seatbelt as a typical manifestation of reactance,Citation21 defined as a defensive reaction to social pressure that results in rejection of the norm and movement in a negative direction.Citation22

Therefore, if there is, as indicated in this study, a “homology” between behavior relating to seatbelt fastening and adherence to medication, we suggest that obedience may also represent a mechanism of patient adherence. Indeed, agreeing that it is good to follow the doctor’s prescription was also an independent determinant of adherence to medication in the multivariate analysis of this study. In contrast, reactance has been proposed as a cause of nonadherence to medication.Citation23

Interestingly, in this study, the axis linking the answers concerning smoking (dots A4–B4 on ) was closer to the “seatbelt” axis than to the “motivation” axis, similarly suggesting that nonsmoking behavior may involve a dimension of obedience. On the other hand, the “motivation” and “priority given to the future” axes seemed close in . These data are consistent with the role of “patience” in motivation concerning health behaviors,Citation24,Citation25 with patience defined as the ability to prioritize the future, preferring a larger, long-term reward (for instance, the beneficial health improvement of tobacco abstinence) rather than a smaller, short-term one (in this example, the pleasure of smoking a cigarette). These speculations call for further investigation.

Dots representing the answers characterizing adherence in clustered in a tight area. It is tempting to hypothesize that patients giving answers that express this “adherent typology” represent the “healthy adherers” who adhere to any recommendation, and this general behavior can explain the puzzling lower mortality rate of patients adhering to a placebo in clinical trials.Citation26 Inversely, nonadherence is very frequent in teenagersCitation27 and may simply represent one of the manifestations of disobedience that is a normal characteristic of this period of life, together with teenagers’ difficulty projecting themselves in the future.Citation28 In an even more speculative mode, in the same way that the patience of individuals that leads to adherenceCitation24 may be, in part, genetically determinedCitation29 and only fully developed in adulthoodCitation30 (which may explain why adherence improves with age),Citation13,Citation31–Citation37 similar hypotheses may be proposed for obedience.

This study has three limitations. First, there was the unavoidable potential bias because the question concerning seatbelt behavior was asked in the framework of a health questionnaire. Second, this study relied only on the answers to a self-reported questionnaire. Third, it is a cross-sectional study, with the general limitations of such investigations. For instance, both adherence and seatbelt fastening were self-reported. There might be differences between this subjective view and respondents’ actual behaviors. It is difficult to determine whether the sample was representative of the population of patients managed by GPs or was a biased sample. Further-more, the median age of the population was 60 years. Younger people may be more prone to fasten their seatbelt because they were asked from childhood to follow this recommendation. In this framework, we did not observe the association (described in some studies,Citation13,Citation31–Citation37 but not all studiesCitation38,Citation39) between age and adherence to medication (P = 0.34, no significance), possibly because 75% of our population was older than 53 years. Further studies are needed to construct and validate a questionnaire to assess obedience in an attempt to evaluate its implications for adherence or nonadherence to medical prescriptions.

Conclusion

These data suggest that some individuals might adhere to medical prescriptions not because they are motivated to do so but simply because, in general, they agree to conform to rules such as fastening their seatbelt when seated in the rear of a car. Others may have both reasons for being adherent. We therefore propose a typological model of adherence to medication (and possibly of adherence in general) with two components: active (motivation) and passive (obedience). This model is consistent with the typological distinction between “critical” and “traditional” adherers proposed by Bader et al for people living with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome, in which traditional (“unquestioning”) adherers have the ability and willingness to follow a therapeutic regimen exactly as prescribed by a medical authority, based on a traditional, asymmetric doctor-patient relationship (paternalistic model). Among “traditional” adherers, Bader et al described a subtype of “faithful” patients who are “obedient and yield readily in a subservient way to doctors’ orders.”Citation40 This attitude may reflect a more general behavior.

Proposing room for obedience in patient behavior may seem provocative because the switch from the word “compliance” to “adherence,” as a means to avoid a connotation that may seem to be in contradiction to the autonomy of the patient, has been presented as a paradigm shift in the understanding of the concept.Citation41 The French word used to describe compliance with medical recommendations is “observance.” This word originally had a religious meaning: “observance de la règle,” obedience to the rule. This is why the word “adhésion,” the translation of the English word adherence, is currently preferred. We suggest that these semantic moves might represent a denial of a reality: as shown, adherence to medication might involve a dimension of obedience in some patients.

Practically, a typological description of adherence, with its two components, motivation and obedience, may help to establish tailored patient-physician relationships able to prevent nonadherence. If nonadherence is the consequence of an inability to prioritize the future while patients manage a chronic disease, it may be helpful to stress the short-term advantages of long-term therapies.Citation24,Citation42 If patients’ behaviors are caused by an innate tendency toward disobedience, a way to reduce the risk of nonadherence would be to avoid presenting the medical prescription in an authoritative way that would lead to reactance.Citation43

From a more theoretical point of view, leaving room for obedience in the mental mechanisms leading to adherence should not be seen as a breach in the concept of patient autonomy but rather as the recognition of the complexity of what is at stake in the patient-physician relationship. Specifically, “empowerment” through patient educationCitation44 can be understood as a process that replaces obedience-driven actions with motivated choices. This conclusion may provide insight into the very meaning of the word “patient” in the framework of this definition. If adherence has two dimensions, active and (as suggested in this study) passive, empowerment would lead the “patient” to become an “agent,” recalling the classical distinction given by Descartes in Passions of the Soul:Citation45 a patient is a subject to whom events happen, whereas an agent is a subject who brings about that they happen:

“To start with, anything that happens is generally labeled by philosophers as a “passion” with regard to the subject to which it happens and an “action” with regard to whatever brings it about that it happens. Thus, although the agent and patient – the maker and the undergoer – are often quite different, an action and passion are always a single thing that has these two names because of the two different subjects to which it may be related.”

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Sanofi-Aventis. The author is grateful to the physicians who participated in the study, to Marmar Kabir Ahmadi and Christian Kempf who performed the statistical analysis, and to Professor Sadek Beloucif for fruitful discussions.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HaynesRBAcklooESahotaNMcDonaldHPYaoXInterventions for enhancing medication adherenceCochrane Database Syst Rev20082CD00001118425859

- LawrenceDBRagucciKRLongLBParrisBSHelferLARelationship of oral antihyperglycemic (sulfonylurea or metformin) medication adherence and hemoglobin A1c goal attainment for HMO patients enrolled in a diabetes disease management programJ Manag Care Pharm200612646647116925454

- RozenfeldYHuntJSPlauschinatCWongKSOral antidiabetic medication adherence and glycemic control in managed careAm J Manag Care2008142717518269302

- HoPMRumsfeldJSMasoudiFAEffect of medication nonadherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitusArch Intern Med2006166171836184117000939

- LeeWCBaluSCobdenDJoshiAVPashosCLPrevalence and economic consequences of medication adherence in diabetes: a systematic literature reviewManag Care Interface2006197314116898343

- SokolMCMcGuiganKAVerbruggeRREpsteinRSImpact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare costMed Care200543652153015908846

- SabatoEAdherence to Long Term Therapies – Evidence for ActionGenevaWorld Health Organization2003

- CurtisJRXiJWestfallAOImproving the prediction of medication compliance: the example of bisphosphonates for osteoporosisMed Care200947333434119194337

- BrookhartMAPatrickARDormuthCAdherence to lipid-lowering therapy and the use of preventive health services: an investigation of the healthy user effectAm J Epidemiol2007166334835417504779

- PerrosPDearyIJFrierBMFactors influencing preference of insulin regimen in people with type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetesDiabetes Res Clin Pract199839123299597371

- SolbergLIDesaiJRO’ConnorPJBishopDBDevlinHMDiabetic patients who smoke: are they different?Ann Fam Med200421263215053280

- AhmedATKarterAJLiuJAlcohol consumption is inversely associated with adherence to diabetes self-care behaviorsDiabet Med200623779580216842486

- BerriganDDoddKTroianoRPKrebs-SmithSMBarbashRBPatterns of health behavior in US adultsPrev Med200336561562312689807

- GirerdXHanonOAnagnostopoulosKCiupekCMouradJJConsoliSEvaluation de l’observance du traitement antihypertenseur par un questionnaire: mise au point et utilisation dans un service spécialisé. [Assessment of antihypertensive compliance using a self-administered questionnaire: development and use in a hypertension clinic]Presse Med2001302110441048 (French)11471275

- WiseRABozarthMAA psychomotor stimulant theory of addictionPsychol Rev19879444694923317472

- ElsterJStrong Feelings, Emotions, Addiction and Human Behavior (Jean Nicod Lectures)Cambridge, MAMIT Press2000

- LanglieJKInterrelationships among preventive health behaviors: a test of competing hypothesesPublic Health Rep1979943216225451130

- WilliamsAFWechslerHInterrelationship of preventive actions in health and other areasHealth Serv Rep197287109699764650413

- MohamedNMohd YusoffMFIsahNOthmanISyed RahimSAPaimanNAnalysis of factors associated with seatbelt wearing among rear passengers in MalaysiaInt J Inj Contr Saf Promot201118131020496187

- GillespieGLAl-NatourAMarcumMSheehanHThe prevalence of seatbelt use among pediatric hospital workersAAOHN J2010581148348620964271

- StreffFMGellerESStrategies for motivating safety belt use: the application of applied behavior analysisHealth Educ Res1986114759

- BrehmJWA Theory of Psychological ReactanceNew YorkAcademic Press1966

- FogartyJSReactance theory and patient noncomplianceSoc Sci Med1997458127712889381240

- ReachGA novel conceptual framework for understanding adherence to long term therapiesPatient Prefer Adherence2008271919920939

- ReachGMichaultABihanHPaulinoCCohenRLe ClésiauHPatients’ impatience is an independent determinant of poor diabetes controlDiabetes Metab562011 [Epub ahead of print.]

- SimpsonSHEurichDTMajumdarSRA meta-analysis of the association between adherence to drug therapy and mortalityBMJ2006333755715

- MorrisADBoyleDIMcMahonADGreeneSAMacDonaldTMNewtonRWAdherence to insulin treatment, glycaemic control, and ketoacidosis in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus The DARTS/MEMO Collaboration. Diabetes Audit and Research in Tayside Scotland. Medicines Monitoring UnitLancet19973509090150515109388398

- FrederickSTime preference and identityLoewensteinGReadDBaumeisterRFTime and Decision: Economic and Psychological Perspectives on Intertemporal ChoiceNew YorkRussel Sage Foundation200389113

- ReachGIs there an impatience genotype leading to non-adherence to long term therapies?Diabetologia20105381562156720407742

- ChristakouABrammerMRubiaKMaturation of limbic corticostriatal activation and connectivity associated with developmental changes in temporal discountingNeuroimage20115421344135420816974

- BriesacherBAAndradeSEFouayziHChanKAComparison of drug adherence rates among patients with seven different medical conditionsPharmacotherapy200828443744318363527

- LeeRTairaDAAdherence to oral hypoglycemic agents in HawaiiPrev Chronic Dis200522A0915888220

- YangYThumulaVPacePFBanahanBF3rdWilkinNELobbWBHigh-risk diabetic patients in Medicare Part D programs: are they getting the recommended ACEI/ARB therapy?J Gen Intern Med201025429830420108127

- ZhuBZhaoZMcCollamPFactors associated with clopidogrel use, adherence, and persistence in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary interventionCurr Med Res Opin201127363364121241206

- ParkDCHertzogCLeventhalHMedication adherence in rheumatoid arthritis patients: older is wiserJ Am Geriatr Soc19994721721839988288

- NetelenbosJCGeusensPPYpmaGBuijsSJAdherence and profile of non-persistence in patients treated for osteoporosis – a large-scale, long-term retrospective study in The NetherlandsOsteoporos Int20112251537154620838773

- AsghariSCourteauJDrouinCAdherence to vascular protection drugs in diabetic patients in Quebec: a population-based analysisDiab Vasc Dis Res20107216717120382781

- JansàMHernándezCVidalMMultidimensional analysis of treatment adherence in patients with multiple chronic conditions. A cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospitalPatient Educ Couns201081216116820167450

- LutfeyKEKetchamJDPatient and provider assessments of adherence and the sources of disparities: evidence from diabetes careHealth Serv Res2005406 Pt 11803181716336549

- BaderAKremerHErlich-TrungenbergerIAn adherence typology: coping, quality of life, and physical symptoms of people living with HIV/AIDS and their adherence to antiretroviral treatmentMed Sci Monit20061212CR49350017136004

- LutfeyKEWishnerWJBeyond “compliance” is “adherence.” Improving the prospect of diabetes careDiabetes Care199922463563910189544

- ReachGObstacles to patient education in chronic diseases: a transtheoretical analysisPatient Educ Couns200977219219619505787

- FogartyJSYoungsGAJrPsychological reactance as a factor in patient noncompliance with medication taking: a field experimentJ Appl Soc Psychol2000301123652391

- FunnellMMAndersonRMArnoldMSEmpowerment: an idea whose time has come in diabetes educationDiabetes Educ199117137411986902

- DescartesR[Passions de l’Ame] (1649), Passions of the SoulSome Texts in Modern Philosophy Available from: http://www.earlymodern-texts.com/pdfbits/despass1.pdfAccessed October 4, 2011