Abstract

Background

Injectable disease-modifying drugs (DMDs) reduce the number of relapses and delay disability progression in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). Regular self-injection can be stressful and impeded by MS symptoms. Auto-injection devices can simplify self-injection, overcome injection-related issues, and increase treatment satisfaction. This study investigated patient responses to an electronic auto-injection device.

Methods

Patients with RRMS (n = 63), aged 18–65 years, naïve to subcutaneous (sc) interferon (IFN) β-1a therapy, were recruited to a Phase IV, observational, open-label, multicenter study (NCT01195870). Patients self-injected sc IFN β-1a using the RebiSmart™ (Merck Serono S.A. – Geneva, Switzerland) electronic auto-injector for 12 weeks, including an initial titration period if recommended by the prescribing physician. In week 12, patients completed a questionnaire comprising of a visual analog scale (VAS) to rate how much they liked using the device, a four-point response question on ease of use (‘very difficult’, ‘difficult’, ‘easy’, or ‘very easy’), and a list of ten device functions to rank, based upon their experiences.

Results

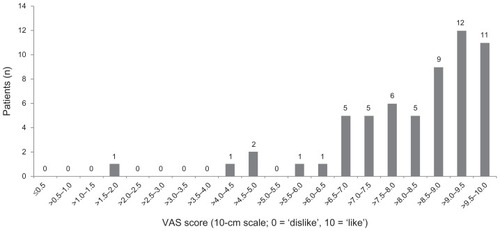

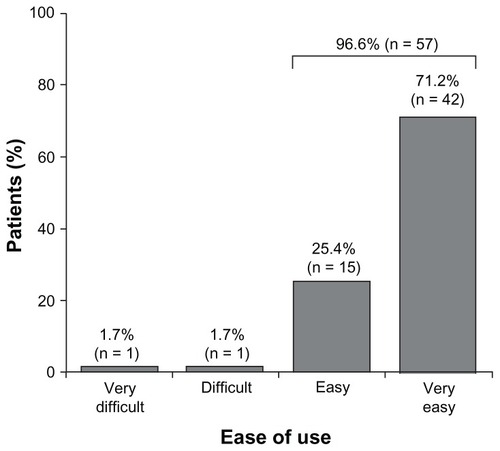

Six patients (9.5%) discontinued the study: one switched to manual injection; two discontinued all treatment; three changed therapy. In total, 59 out of 63 patients (93.7%) completed the VAS; 54 out of 59 (91.5%; 95% confidence interval: 81.3%–97.2%) ‘liked’ using the electronic auto-injector (score ≥6), whereas 57 out of 59 (96.6%) rated the device overall as ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ to use. Device features rated as most useful were the hidden needle (mean [standard deviation] score: 3.3 [3.01]; n = 56), confirmation sound (3.9 [2.45]), and multidose cartridge (4.6 [2.32]). The least useful functions were the dose history list (8.0 [2.57]) and dose history calendar (7.5 [2.30]).

Conclusions

These findings suggest that the electronic auto-injector may be suitable for patients who are new to injectable DMD therapy. Devices that simplify the injection process may help to ensure that patients receive the full benefits of treatment.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system.Citation1 Patients with relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS) experience episodes of acute worsening of neurologic function, followed by a variable degree of recovery.Citation2 Several injectable disease-modifying drugs (DMDs) are available that have been shown to reduce relapses and that may delay progression of disability in patients with MS;Citation3–Citation6 however, these drugs require frequent administration.

MS therapy is rapidly evolving with the recent introduction of oral agents in some countries, but self-injectable DMDs are expected to remain the first-line treatment for MS in Europe, because of the favorable long-term efficacy, safety, and tolerability data available for these agents.Citation5,Citation7,Citation8 Regular self-injections can be stressful for many patients, and symptoms of MS, such as cognitive impairment and impaired motor skills, may impede self-injection.Citation9 Such issues, in addition to needle phobia, injection anxiety, perceived lack of efficacy, and concerns over injection-related adverse events, can negatively impact treatment acceptance, adherence,Citation10–Citation13 and, ultimately, efficacy.Citation14 Adherence to long-term therapies is defined by the World Health Organization as “the extent to which a person’s behavior – taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle change – corresponds with agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider”.Citation15 Adherence to treatment may be improved through patient education, correct injection technique, the management of expectations, and accurate monitoring of adherence.Citation16

Innovative delivery devices have been designed to improve the injection experience and thus potentially improve both adherence to treatment and clinical outcomes.

Auto-injection devices are available for most DMDs and can simplify the injection process, overcome injection-related issues, and improve treatment satisfaction.Citation17,Citation18 An electronic auto-injection device () (RebiSmart™; Merck Serono S.A. – Geneva, Switzerland, a branch of Merck Serono S.A., Coinsins, Switzerland, an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) has been developed for the subcutaneous (sc) administration of interferon (IFN) β-1a. In an international user trial assessing the auto-injection device, 71.6% of patients considered the device ‘very suitable’ or ‘suitable’ for self-injection, and 92.2% reported some degree of suitability. In addition, each device function was rated ‘very useful’ or ‘useful’ by at least 80% of patients.Citation19

Figure 1 The RebiSmart™ device.

Image reproduced with permission from Merck Serono S.A. – Geneva, Switzerland, a branch of Merck Serono SA, Coinsins, Switzerland, an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

The present study was performed to investigate patient response to an electronic auto-injection device in the UK and Ireland, including ease of use and the three device functions that patients found most useful.

Methods

Study design

This was a Phase IV, observational, open-label, multicenter study of patient use of and response to an electronic autoinjection device in the UK and Ireland (NCT01195870). Patients who were treatment-naïve to sc IFN β-1a (Merck Serono S.A., Rebif®; Geneva, Switzerland) were given the option to choose from manually injecting using a prefilled syringe, using the standard Rebiject™ II auto-injector (Merck Serono S.A. – Geneva, Switzerland), or using the RebiSmart™ electronic auto-injector. If patients elected to use the electronic auto-injector, they were invited to enter the study and received training in the use and maintenance of the auto-injection device by an MS nurse using standard training materials. Patients self-injected sc IFN β-1a using the electronic auto-injector for 12 weeks, which included an initial titration period if recommended by the prescribing physician. As per the drug label recommendations, prior to injection, and for an additional 24 hours after each injection, use of an antipyretic analgesic was advised to decrease ‘flu-like’ symptoms (FLS) associated with sc IFN β-1a administration. This observational study did not require Independent Ethics Committee approval within the UK, although approval was sought and obtained in Ireland. Patient materials were approved by each site’s Research and Development Committee. This study was performed in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (European Clinical Trials Directive 2001/20/EC),Citation20,Citation21 all applicable local regulations, and the Declaration of Helsinki.Citation22

Patients

Patients aged 18–65 years were eligible for the study if they had RRMS (according to the Association of British Neurologists criteriaCitation23 in the UK and the revised 2005 McDonald criteriaCitation24 in Ireland); were scheduled to start sc IFN β-1a, administered three times weekly, for the first time; chose to use the electronic auto-injector; were under review by an MS nurse; and gave written informed consent to participate in the study. Patients were excluded if they did not self-inject, were unable to use the electronic auto-injector owing to visual or physical impairment, were unwilling to give informed consent, had a contraindication to sc IFN β-1a as defined in the summary of product characteristics, or had any allergy to antipyretic analgesics that were advised as prophylaxis for FLS.

Assessment

After 12 weeks, patients were assessed according to standard care in the patients’ usual MS clinics, and asked to complete a questionnaire. The questionnaire comprised of a visual analog scale (VAS) on which patients indicated how much they liked using the electronic auto-injector (10-cm scale; 0 = ‘dislike’, 10 = ‘like’), a four-point response question on ease of use of the device (‘very difficult’, ‘difficult’, ‘easy’, or ‘very easy’), and a list of ten device functions to rank based upon their experiences (1 = most useful function; 10 = least useful function; ). To allow for adjustments to clinical appointments or occurrence of patient holidays around week 12, completion of the questionnaire was permitted within a window of 11 to 16 weeks following training and initiation of treatment. In exceptional circumstances, if a patient could not attend the clinic within the window of 11 to 16 weeks they were asked to complete the questionnaire by week 16 and return it by post. Patients who discontinued using the electronic auto-injector before week 12, but who continued to participate in the study, completed the questionnaire.

Table 1 Rank and summary statistics of the recorded score for each of the ten device functions in the rank population

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was the percentage of patients who liked using the device (VAS score of ≥6) at the end of the 12-week treatment period. Secondary endpoints at week 12 were the percentage of patients who found the device ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ to use, and the top three device functions that patients found most useful, from a ten-point list of functions.

Study size

The primary hypothesis was that the proportions of patients who liked and disliked using the electronic auto-injector would be unequal, and that an estimated 70% of patients would like using the electronic auto-injector. The null hypothesis was that 50% of patients would like using the electronic auto-injector. To reject the null hypothesis, using a two-sided test with 5% significance level and 80% power, 47 patients were required. To account for an expected dropout rate of 25%, a total of 63 patients were necessary. Sample size was calculated using a one-sample χ-squared test with normal approximation.

Statistical analysis

The ‘completers population’ was defined as all patients who completed the VAS. The ‘rank population’ was defined as all patients who ranked all ten device functions in order of preference. All endpoints were summarized using descriptive statistics, with primary endpoint results presented as percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and secondary endpoint results presented as numbers with percentages or means with standard deviations (SDs). The primary hypothesis was retested in a sensitivity analysis, which took into account all patients who entered the study. Scoring for each of the ten device functions was analyzed using summary statistics, and ranked in ascending order, so that the function with the lowest mean score gave the highest rank. The number of weeks a patient used the electronic auto-injector before discontinuing was also analyzed using summary statistics. All statistical tests were two-sided and performed at the 5% significance level using SAS software (v 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient disposition

A total of 63 patients were enrolled in the survey from ten participating sites in the UK and Ireland, between October 2009 and September 2010. Six patients completed the questionnaire outside the protocol-specified time window of 11 to 16 weeks. However, as this was an observational study and these patients returned to the clinic and completed their questionnaires between 9.9 and 18 weeks, they were included in the primary analysis. Six of the 63 patients (9.5%) discontinued the study (all of whom completed the questionnaire at discontinuation). Reasons for discontinuation included a switch to manual sc IFN β-1a injection (n = 1 patient), discontinuation of all treatment (n = 2), and a change in therapy (n = 3). These patients had used the electronic auto-injector for a mean (SD) of 6.8 (2.79) weeks before discontinuation.

Patient opinion of the auto-injector

In total, 59 out of 63 (93.7%) recruited patients completed the VAS and were included in the completers population for the primary endpoint. In the completers population, 54 out of 59 patients (91.5%; 95% CI: 81.3%–97.2%) scored ≥6 on the VAS and reported that they liked using the electronic auto-injector (); mean (SD) VAS score was 8.4 (1.6). In the sensitivity analysis, 56 out of 63 patients (88.9%; 95% CI: 78.4%–95.4%) scored ≥6 on the VAS.

Ease of device use and usefulness of device functions

In the population of patients who completed the survey, 57 out of 59 patients (96.6%) rated the device as ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ to use (). The device feature rated as most useful by the ‘rank’ population (n = 56) was the hidden needle, followed by the confirmation sound, and having all three doses required for 1 week’s treatment in a single cartridge (). Other device functions (injection button lights up, stepwise injection guide on screen, last injection indicator, comfort settings, and dose indicator) were all ranked similarly. Patients considered the least useful functions to be the dose history calendar and dose history list.

Discussion

The electronic auto-injection device was developed to address some of the known factors that affect patient adherence to injectable DMDs,Citation25 as well as the concerns and needs of patients with MS. Needle phobia, self-injection psychology, forgetting to inject, injection-related pain, skin-site reactions, and travel (eg, the need to take cumbersome equipment) all impact on adherence to self-medication.Citation10,Citation12 This study showed that the majority of patients liked the auto-injection device (91.5%) and found it ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ to use (96.6%), both of which may lead to increased treatment adherence. Furthermore, results of the sensitivity analysis, in which 88.9% of patients scored ≥6 on the VAS, support the primary analysis findings.

The hidden needle was considered to be the most useful device function, followed by the audible cue to confirm correct administration of the injection, and having three doses (1 week’s treatment) in a single cartridge. Concealment of the needle throughout the injection process was very important to a selection of patients who were needle phobic and who did not want to see the needle before or after the injection. A concealed needle also reduces the potential for patient injury through mishandling of the device, and it increases injection discretion. The confirmation sound may aid injection in out-of-sight areas, while the multidose cartridge increases convenience. In addition, the handheld device is portable, does not require refrigerated storage,Citation26 and reduces waste associated with single-use prefilled syringes and single-use injection pens.

The least useful functions, as ranked by patients, were the dose history calendar and dose history list. However, in this 12-week study, patients may have been unaware of the benefits of recording dose history, and such functions may become more beneficial to patients for assisting long-term adherence. In theory, the dose history features may help to promote dialog between healthcare professionals (HCPs) and patients, which is important as treatment and device choice should be a joint decision. In addition, the dose history features may help HCPs to avoid escalating treatment in patients who are non-adherent to their present treatment regimen.

Although a dosing history log may not be of importance to patients, the data relating to dose history are likely to be of interest to payers, who may have access to these data in the UK; for instance, unused or wasted drugs cost the National Health Service at least £100 million (approximately US$165 million) every year.Citation27 Furthermore, clinicians may be able to justify their choice of DMD by monitoring patient adherence. The incorporation of adherence data into patient databases may offer the potential to correlate the extent of drug usage to treatment outcome. The dosing log may also provide valuable information in clinical trials and in clinical practice, where assessments of efficacy may otherwise be influenced by the patient’s subjective reporting of adherence. Citation28 Patient training and education on use of the dosing log may contribute to a more accurate understanding of the benefits that the function offers, and increase the perceived usefulness of this function. The dosing log may be beneficial to patients with mild cognitive impairment as a memory aid, preventing double dosing and missed injections.

Results from this study support findings from a previous study, in which 95.2% of patients found the functions of the same device ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ to use, and overall convenience was rated as the most important benefit of the device.Citation19 Although a slightly different range of device features was ranked by patients in the previous study, all features, including injection confirmation sound, last injection display, and dose history, were rated as ‘useful’ or ‘very useful’ by at least 80% of patients.Citation19 Results to date suggest that the electronic auto-injection device may be suitable for patients who are not satisfied with their current method of self-injection or for those who are new to DMD therapy.

The findings of the present study must be considered in the context of the study limitations, including the subjective nature of the scales used, which are difficult to validate. Patients may have found it difficult to interpret differences between ‘very difficult’, ‘difficult’, ‘easy’, or ‘very easy’ when rating ease of use using a four-point response question. Bias may have been introduced into the study at enrollment as only those patients who elected to use the auto-injection device from a selection of DMD administration options were invited to participate. Cognitive function was not assessed, which may have been useful for determining whether the dosing log would be of benefit to patients with cognitive impairment and whether responses to the questionnaire were affected by patients with cognitive impairment. In addition, the potential benefits of the dosing log for avoiding the risk of double dosing may not have been clearly explained to, or fully understood by, patients. With only 63 patients, the study population was small. Further, six patients discontinued the study. Although study discontinuations could not reasonably be attributed to the electronic auto-injection device, the reasons for switching to manual injection or another therapy or discontinuing treatment were not recorded.

A longitudinal study with a larger sample may be more informative in future trials because patients with MS require long-term therapy. Long-term treatment has been associated with treatment fatigue,Citation13 so it would be interesting to evaluate in patients – who are not naïve to DMDs – if switching to a new injection device could re-stimulate interest in injectable therapy and subsequently increase adherence. As patients in this study were naïve to treatment, they would not have been able to compare the additional features of the electronic autoinjection device with those of other injection devices. It would be interesting to examine treatment adherence and disease outcomes in patients using the electronic autoinjection device compared with those using other delivery methods in a longitudinal study. Although it will be important to assess device adherence in a longitudinal study, shorter studies are useful for identifying the factors that influence early device discontinuation.

Use of an auto-injection device may improve concordance, particularly in patients with visual or cognitive impairment, or impaired dexterity.Citation18 Auto-injection devices reduce injection-site reactions compared with manual injection,Citation18 and improvements in devices to simplify the process and reduce discomfort have been associated with reduced injection pain and increased treatment satisfaction.Citation17,Citation19

Conclusion

The results of this study in patients with RRMS suggest that most patients liked the electronic auto-injection device and found it ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ to use. Concealment of the needle throughout the injection process was found to be the most useful feature of the device. These findings, along with those of a previous study assessing the suitability of the same device,Citation19 suggest that the electronic auto-injector may be suitable for patients who are new to injectable DMD therapy. Devices play an important role in the individualized treatment of patients receiving self-injectable DMDs and may help to ensure that patients receive the full benefits of treatment.

Acknowledgments and disclosure

Marketing authorization for the use of the RebiSmart™ device and the serum-free formulation of sc IFN β-1a (free from fetal bovine serum and human serum albumin), at a tiw dosing regimen, has been granted in Europe by the European Medicines Agency (EMA), Canada, Australia, and other countries for relapsing MS. This therapy is not currently approved by other regulatory authorities, including the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Neither the serum-free nor serum-containing formulation is approved in any territory for treatment of patients with a first clinical demyelinating event.

Caroline D’Arcy has received honoraria from Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Novartis, and Bayer Schering; and financial support for a newly diagnosed study day from Teva. Del Thomas has received honoraria and consultation fees from Merck Serono and Novartis. Laura Parkes and Dee Stoneman are employees of Merck Serono Ltd, UK, an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

This study was supported by Merck Serono Ltd, Feltham, Middlesex, UK, an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. The authors thank Satellite for data management and analysis, and their co-investigators in the RebiSmart™ User Trial: UK – J Curlis, G Smith (Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne); S Gaughan, M Moir-Holland (Lincoln County Hospital, Lincoln); G Mazibrada, S Colhoun, S Le Tissier (Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham); M Burgess, C Allen, A Bradford, D Winterbottom, G Carter, M Jackson, E Hartley, W Power (Manchester Hope Hospital, Salford); C Lowndes (North Staffordshire Royal Infirmary, Stoke-on- Trent); K Mutch, H Leggett (Walton Centre NHS Foundation Trust, Fazakerley); D Owen, G Watkins (Bristol Frenchay Hospital, Bristol). Ireland – N Tubridy, L Gribbin, S Jordan (St Vincent’s University Hospital, Dublin).

The authors also thank John Wiltshire and Alyson Bexfield of Caudex Medical Ltd, Oxford, UK (supported by Merck Serono Ltd, Feltham, Middlesex, UK, an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), for assistance with preparing the initial draft of the manuscript, collating the comments of authors and other named contributors, assembling the table and figures, and coordinating submission requirements.

References

- BennettJLStuveOUpdate on inflammation, neurodegeneration, and immunoregulation in multiple sclerosis: therapeutic implicationsClin Neuropharmacol20093212113219483479

- LublinFDReingoldSCDefining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA) Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of New Agents in Multiple SclerosisNeurology1996469079118780061

- JacobsLDCookfairDLRudickRAIntramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosisAnn Neurol1996392852948602746

- JohnsonKPBrooksBRCohenJACopolymer 1 reduces relapse rate and improves disability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results of a phase III multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialNeurology199545126812767617181

- PRISMS Study GroupRandomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of interferon beta-1a in relapsing/remitting multiple sclerosisLancet Neurol199835214981504

- The IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study GroupInterferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. I. Clinical results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialNeurology1993436556618469318

- KapposLTraboulseeAConstantinescuCLong-term subcutaneous interferon beta-1a therapy in patients with relapsing-remitting MSNeurology20066794495317000959

- PRISMS Study Group, University of British Columbia MS/MRI Analysis GroupPRISMS-4: long-term efficacy of interferon-beta-1a in relapsing MSNeurology2001561628163611425926

- CostelloKKennedyPScanzilloJRecognizing nonadherence in patients with multiple sclerosis and maintaining treatment adherence in the long termMedscape J Med20081022519008986

- CoxDStoneJManaging self-injection difficulties in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosisJ Neurosci Nurs20063816717116817668

- MohrDCBoudewynACLikoskyWInjectable medication for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: the influence of self-efficacy expectations and injection anxiety on adherence and ability to self-injectAnn Behav Med20012312513211394554

- TreadawayKCutterGSalterAFactors that influence adherence with disease-modifying therapy in MSJ Neurol200925656857619444532

- TremlettHLOgerJInterrupted therapy: stopping and switching of the beta-interferons prescribed for MSNeurology20036155155412939437

- Al-SabbaghABennetRKozmaCMedication gaps in disease-modifying therapy for multiple sclerosis are associated with an increased risk of relapse: findings from a national managed care databaseJ Neurol2008255Suppl 2S79

- World Health OrganizationAdherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_report/en/index.htmlAccessed August 24, 2011

- LugaresiAAddressing the need for increased adherence to multiple sclerosis therapy: can delivery technology enhance patient motivationExpert Opin Drug Deliv20096995100219637982

- CramerJACuffelBJDivanVPatient satisfaction with an injection device for multiple sclerosis treatmentActa Neurol Scand200611315616216441244

- MikolDLopez-BresnahanMTaraskiewiczSA randomized, multicentre, open-label, parallel-group trial of the tolerability of interferon beta-1a (Rebif) administered by auto-injection or manual injection in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosisMult Scler20051158559116193898

- DevonshireVArbizuTBorreBPatient-rated suitability of a novel electronic device for self-injection of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis: an international, single-arm, multicentre, Phase IIIb studyBMC Neurol2010102820433746

- International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human UseGuideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R1) Available from: http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E6_R1/Step4/E6_R1_Guideline.pdfAccessed July 11, 2011

- The European Parliament and the Council of the European UnionDirective 2001/20/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 April 2001 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States relating to the implementation of good clinical practice in the conduct of clinical trials on medicinal products for human use Available from: http://www.eortc.be/Services/Doc/clinical-EU-directive-04-April-01.pdfAccessed July 11, 2011

- World Medical AssociationDeclaration of Helsinki: Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects1996

- Association of British NeurologistsRevised (2009) Association of British Neurologists’ guidelines for prescribing in multiple sclerosis Available from: http://www.abn.org.uk/abn/userfiles/file/ABN_MS_Guidelines_2009_Final(1).pdfAccessed July 21, 2011

- PolmanCHReingoldSCEdanGDiagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald Criteria”Ann Neurol20055884084616283615

- ExellSVerdunEDriebergenRA new electronic device for subcutaneous injection of IFN beta-1aExpert Rev Med Devices2011854355321728909

- Merck Serono Launches RebiSmart™, First Electronic Injection Device For Delivery of Multiple Sclerosis Treatment Rebif®News releaseJune 242009 Available from: http://www.merckserono.com/corp.merckserono/en/images/20090624_en_tcm112_42119.pdfAccessed July 11, 2011

- National Audit OfficePrescribing costs in primary care Available from: http://www.nao.org.uk/publications/0607/prescribing_costs_in_primary_c.aspxAccessed February 24, 2011

- BruceJMHancockLMLynchSGObjective adherence monitoring in multiple sclerosis: initial validation and association with self-reportMult Scler20101611212019995835