Abstract

Objective

Due to the rapid proliferation of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) treatment options, there is a need for health care providers with knowledge of antiretroviral therapy intricacies. In a HIV multidisciplinary care team, the HIV pharmacist is well-equipped to provide this expertise. We conducted a systematic review to assess the impact of HIV pharmacists on HIV clinical outcomes.

Methods

We searched six electronic databases from January 1, 1980 to June 1, 2011 and included all quantitative studies that examined pharmacist’s roles in the clinical care of HIV-positive adults. Primary outcomes were antiretroviral adherence, viral load, and CD4+ cell count and secondary outcomes included health care utilization parameters, antiretroviral modifications, and other descriptive variables.

Results

Thirty-two publications were included. Despite methodological limitation, the involvement of HIV pharmacists was associated with statistically significant adherence improvements and positive impact on viral suppression in the majority of studies.

Conclusion

This systematic review provides evidence of the beneficial impact of HIV pharmacists on HIV treatment outcomes and offers suggestions for future research.

Introduction

Since the first reported cases of AIDS in 1981Citation1 and the emergence of the global human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) pandemic, the field of antiretroviral (ARV) therapy has undergone extraordinary changes and continues to witness dramatic progress. The availability of over two dozen distinct ARVs, providing more tolerable and safer agents, and the ability to tailor ARV regimens to individual patients, demonstrates the substantial advancement in the field and the heightened understanding and expertise that is required to minimize drug interactions, contraindications, and adverse effects. The increased incidence of comorbidities in the aging HIV-positive population demands close monitoring and a keen awareness of the interplay between various therapies, the transmission of drug resistant viruses requires knowledge of ARV regimen selection, and the need for life-long therapy necessitates high ARV adherence and long-term follow-up. Therefore, the HIV clinical pharmacist has emerged as an indispensable member of the HIV multidisciplinary care team.

Publications as early as 1991 have described the involvement of pharmacists in clinics and hospital teams caring for HIV-positive individuals.Citation2–Citation4 These and other studiesCitation5,Citation6 demonstrate the importance of the pharmacist’s medication expertise and involvement in the multidisciplinary care team. Most recently, Horberg et alCitation7 examined the components of the HIV multidisciplinary care team that are associated with the greatest increases in ARV adherence. The involvement of clinical pharmacists represented the first branch of the regression tree (signifying the component of the care team with the greatest impact on adherence) and the presence of clinical pharmacists resulted in statistically significant improvements in adherence in conjunction with any multidisciplinary care team member.

Given the extensive history and indications that clinical pharmacists may be particularly valuable in the medical care of HIV-positive individuals, we conducted a systematic review to assess the contributions of HIV pharmacists on HIV clinical outcomes, including ARV adherence and virologic and immunologic parameters. The purpose of this review was to systematically evaluate the research conducted to date and identify gaps in our knowledge regarding the impact of HIV clinical pharmacists in the clinical care of those living with HIV/AIDS.

Methods

Objective

The primary objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the impact of clinical pharmacists on HIV clinical outcomes. Primary outcomes included ARV adherence, HIV viral load suppression, and CD4+ cell count. Secondary outcomes consisted of health care utilization parameters, antiretroviral modifications, and other descriptive variables.

Data sources

We searched PubMed, EMBASE®, Cochrane Library, Web of Science®, BIOSIS Previews, and PsycINFO® from 1980 (or the respective date of inception of each database) until June 1, 2011. Additionally, we conducted a manual search by screening the references of pertinent articles and identifying any additional relevant publications that were not previously included. Due to incomplete data presentation in conference abstracts, we did not include conference proceedings and abstracts in this review.

Search strategy

We conducted our search strategy in the style of Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy to identify all relevant published studies.Citation8 We included randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials, before-after comparisons, historically controlled trials, cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, case-control studies, and descriptive studies, as well as appropriate medical subject headings (MeSH) terms, and a wide range of relevant search terms in all databases. The detailed search strategy used for PubMed can be found in . This strategy was modified as appropriate for use in other databases.

Table 1 Example of search strategy used in PubMed

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included all studies that examined the role of a pharmacist in the clinical care of HIV-infected adults. Studies were divided into two broad categories based on the researchers’ prespecified intentions in examining the impact of pharmacists. The first category encompassed “intervention studies”; these studies included HIV pharmacist activities that were part of a study protocol and were only implemented for the purpose of research upon receipt of informed consent. The second category included studies of “clinical care activities”; defined as studies which examined pharmacist actions that were taken as part of routine patient care and which examined specific outcomes (eg, the impact of an existing pharmacist adherence clinic on adherence). These clinical care activities were not conducted for the purpose of research and would have occurred regardless of the study. The reason for this classification was to assess the rigor of the research and the evolution of publications regarding HIV clinical pharmacists over time. Studies that did not include details of the pharmacist’s involvement, but specifically mentioned any pharmacist participation were included. Multifactorial interventions or clinical care activities were included as long as at least one factor clearly indicated pharmacist contributions.

We also classified the pharmacist role as being central or peripheral to the study objectives. The pharmacist role was considered “central” in studies that were specifically designed to examine the influence of pharmacists on the care of HIV-positive individuals. Studies where the role of the pharmacist was “peripheral” were those in which the pharmacist was involved in carrying out the study objectives, but the research was not designed to examine the sole impact of the pharmacist.

We did not include studies that exclusively assessed pharmacist’s ability to provide HIV prevention services or studies that only assessed pharmacy operations (such as medication stock, home delivery, medication packaging, etc). Studies were included without regard to the location where they were conducted, but were limited to English language publications. Research that was purely qualitative was excluded.

Review methods and data abstraction

Using EndNote software package (X5.0.1; Thomson Reuters, New York, NY) relevant studies were located in the above-mentioned data sources and duplicates and irrelevant articles were extracted by one author (PS). Two authors (PS, JC) independently read the remaining citations and identified eligible studies based on prespecified inclusion/exclusion criteria. All uncertainties and disagreements were arbitrated by a third author (BD). Using a data abstraction form, three authors (PS, JC, BD) summarized pertinent information from included articles and over 30% of all abstracted data was re-examined by another author to ensure data accuracy. We utilized the Cochrane guide for study assessment checklist to assign the study design to each included study.Citation9

Outcome variables

The primary outcome of this review focused on the impact of the pharmacist on ARV adherence, HIV viral load, and CD4+ cell count. Secondary outcomes included change in the number of physician or emergency room visits, change in pill burden (ie, frequency of daily dosing or quantity of pills per day), cost effectiveness or any cost containment data, discontinuation or initiation of opportunistic infection prophylaxis or treatment, percentage of clinical care activities accepted by the attending physician or team, change in patients’ or providers’ HIV knowledge, impact on ARV drug resistance, and reports of the number of clinical care activities conducted by the pharmacist (eg, identification of dose errors, initiation/discontinuation/consolidation of ARVs, adverse effect and drug interaction detection and management, resolution of medication adherence issues, and provision of drug information). Given the variability in assessment, analysis, and presentation of outcomes in identified studies, we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis.

Results

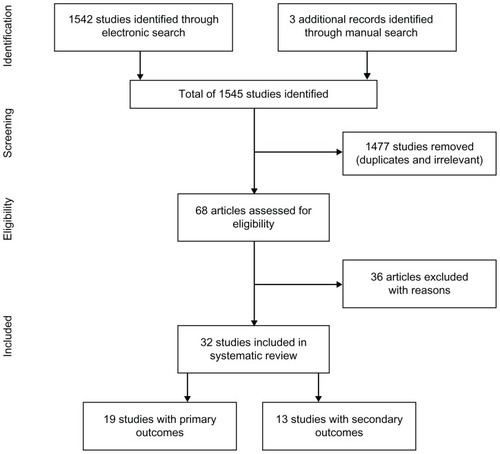

From 1545 search matches, 68 articles were assessed for eligibility and, of these, 36 were excluded because they were published in a language other than English (n = 3), were in abstract form (n = 11), were review articles (n = 3), were qualitative studies (n = 4), or were not regarding pharmacist clinical care activities or intervention (n = 15) (). Thirty-two publications met our eligibility criteria and were included.Citation10–Citation41 Among these publications, 19 evaluated the primary outcomes of interestCitation10–Citation28 and 13 contained information on the secondary outcomes.Citation29–Citation41 and summarize these studies.

Table 2 Summary of studies with primary outcomes

Table 3 Summary of studies with secondary outcomes

Publications evaluating HIV clinical pharmacists’ impact on primary outcomes

These studies were published between 2000 and 2011 and were primarily conducted in the US (68%). Observational cohort studies (32%) and before-after comparisons (32%) were the most common study designs. Baseline sample sizes ranged from 28 to 7018 (median = 64); in studies that reported mean age, participant mean age ranged from 36 years to 49 years; and the percentage of male study participants ranged from 0% to 100% (median = 80%). The percentage of participants who were Black ranged from 15% to 83% (median = 26%; not stated in 32% of studies); the proportion of White participants ranged from 12% to 71% (median = 52%; not stated in 32% of studies); and the percentage of men who have sex with men (MSM) ranged from 0% to 70% (median = 51%; not stated in 47% of studies). The pharmacist played a central role in the study objectives of 53% of included publicationsCitation11,Citation14,Citation15,Citation17,Citation20,Citation21,Citation24,Citation25,Citation27,Citation28 and 63% of studies examined the impact of pharmacist interventions (see Methods section for definition).Citation10–Citation13,Citation15,Citation17,Citation19,Citation20,Citation22–Citation24,Citation26

The majority of the reviewed studies examined the impact of pharmacists in HIV ambulatory care clinic setting (63%),Citation10–Citation12,Citation15–Citation21,Citation25,Citation28 followed by outpatient community pharmacies (26%).Citation14,Citation22,Citation24,Citation26,Citation27 The main pharmacist role was the provision of medication adherence counseling and tools for adherence improvement (including pill boxes, refill reminders, beepers, alarms, medication schedules, blister packs, medication diaries, etc). Other pharmacist activities included patient education (regarding dosing, adverse effects, drug interactions, medication storage, missed doses, adherence, methods of improving adherence, etc); ARV regimen selection; ARV initiation, discontinuation, and dose adjustment for renal/hepatic impairment; and monitoring for ARV adverse effects and drug interactions.

ARV adherence

In the 18 studies that examined ARV adherenceCitation10–Citation19,Citation21–Citation28 (adherence not assessed in March et alCitation20), the most common method of adherence assessment was based on medication refill records (56%), followed by patient self-report (33%), and electronic drug monitoring using medication event monitoring systems (MEMS®, 28%). Other less frequently used methods included pill count and therapeutic drug level monitoring. Approximately 78% of studies used only one adherence assessment method and 17% used two methods.

Among the 10 publications in which the pharmacist’s role was central,Citation11,Citation14,Citation15,Citation17,Citation20,Citation21,Citation24,Citation25,Citation27,Citation28 adherence was compared between the pharmacist group versus a control group in eight studies;Citation11,Citation14,Citation15,Citation17,Citation21,Citation25,Citation27,Citation28 all of which found an association between assignment to the pharmacist group and improved adherence outcomes. Nine studies examined interventions or clinical care activities where the pharmacist had a peripheral role,Citation10,Citation12,Citation13,Citation16,Citation18,Citation19,Citation22,Citation23,Citation26 among which five reported medication adherence outcomes by comparing the pharmacist group versus a control group.Citation13,Citation16,Citation18,Citation22,Citation26 Four of these studies reported a positive association between adherence and allocation to the pharmacist groupCitation13,Citation16,Citation22,Citation26 and one showed no statistically significant difference between the two arms.Citation18

Among 13 studies that compared adherence outcomes of a pharmacist-engaged study arm versus a control arm,Citation11,Citation13–Citation18,Citation21,Citation22,Citation24–Citation26,Citation28 nine reported percent ARV adherence as a continuous outcome in each group at the end of the follow-up period.Citation11,Citation13,Citation16–Citation18,Citation21,Citation24–Citation26 In these studies, adherence in the pharmacist arm was 2%–59% (median = 19%) higher as compared to the control arm. Four studies used other methods of comparison to present the impact of pharmacist care on adherence.Citation14,Citation15,Citation22,Citation28 Castillo et al,Citation14 found that 14.7% more patients who obtained service from AIDS tertiary care hospital pharmacies had >90% adherence compared to those with no pharmacist contact. Hirsch et al,Citation22 found that 18.2% more patients receiving ARVs from pilot Medi-Cal pharmacies, featuring pharmacists with HIV training, had an adherence of 80%–120% in comparison to those not enrolled in this program. In a study by Henderson et al,Citation28 25% more patients had >95% adherence after referral to the pharmacist-managed clinic versus prior to referral. Lastly, Levy et alCitation15 reported that participants missed 1.2 fewer doses in the past 7 days after receipt of a pharmacist-provided adherence education session versus the period of observation prior to this intervention.

HIV viral load

Among the ten studies that assessed the central role of the pharmacist,Citation11,Citation14,Citation15,Citation17,Citation20,Citation21,Citation24,Citation25,Citation27,Citation28 nine examined viral load outcomes.Citation11,Citation14,Citation15,Citation17,Citation20,Citation21,Citation25,Citation27,Citation28 In six of these studies, pharmacist involvement was associated with clinically or statistically significant viral load reductions or a greater proportion of maximal viral suppression,Citation14,Citation17,Citation20,Citation21,Citation25,Citation28 while in three, no association with pharmacist care was observed.Citation11,Citation15,Citation27 The pharmacist assumed a peripheral role in nine studies,Citation10,Citation12,Citation13,Citation16,Citation18,Citation19,Citation22,Citation23,Citation26 among which five reported virologic outcomes.Citation12,Citation13,Citation18,Citation19,Citation23 In four of these studies, a favorable association was noted between viral load reduction and allocation to the pharmacist-involved study arm,Citation12,Citation13,Citation18,Citation23 whereas no relationship between virologic response and pharmacist care was reported by one study.Citation19

CD4+ cell count

In the ten studies where a pharmacist played a central role, seven also assessed immunologic outcomes.Citation11,Citation15,Citation17,Citation20,Citation21,Citation25,Citation27 Among these studies, two revealed an increase in CD4+ cell count related to receipt of pharmacist careCitation20,Citation25 and five showed no association.Citation11,Citation15,Citation17,Citation21,Citation27 Of the nine studies in which the pharmacist had a peripheral role, only two reported immunologic outcomesCitation18,Citation19 and in both no relationship was seen between the pharmacist arm versus the control arm.

Other outcomes

Among the ten studies investigating the pharmacist’s central role, several reported other favorable outcomes, including an increase in adherence to clinic appointments and reductions in variables such as hospitalizations,Citation11 ARV toxicity scores,Citation20 physician office visits, number of hospital days, emergency department visits,Citation21 pill burden, and daily dosing frequency.Citation25 Other outcomes in the nine studies where the pharmacist assumed a peripheral role included no changes in variables such as ARV adherence self-efficacy,Citation13 retention on ARV at 12 months,Citation18 and frequency of incident opportunistic infections.Citation22,Citation26 However, there were increases in the time on ARV therapy,Citation18 improved appointment keeping,Citation19 higher likelihood of remaining on ARV,Citation22,Citation26 fewer contraindicated ARV regimens,Citation22,Citation26 and a higher cost in the study arm involving the pharmacist.Citation19,Citation22

Publications evaluating HIV clinical pharmacists’ impact on secondary outcomes

These studies were published between 1992 and 2011 and 69% were conducted in the US. Approximately 80% of these studies were descriptive in nature. Baseline sample sizes ranged from 31 to 285 (median = 70); in studies reporting mean age, participant mean age ranged from 36 years to 65 years (age not stated in 38% of studies); percentage of male study participants ranged from 49% to 100% (median = 71%; not stated in 31% of studies). The percentage of participants who were Black ranged from 27% to 82% (median = 53%; not stated in 69% of studies); proportion of participants who were White ranged from 18% to 53% (median = 20%; not stated in 62% of studies); and percentage of MSM ranged from 6% to 26% (not stated in 85% of studies).

In 92% of these studies, the central role of a pharmacist was evaluatedCitation29–Citation38,Citation40,Citation41 and approximately 85%–100% of the pharmacists’ suggestions were accepted by the physician or health care team. Sixty-nine percent of studies examined pharmacists’ impact in the inpatient medical center settingCitation30–Citation32,Citation34,Citation37–Citation41 and 23% assessed this role in the outpatient ambulatory care clinics.Citation29,Citation33,Citation35 The clinical care activities performed by pharmacists in these reports included adjustments in drug doses, medication initiation/discontinuation, monitoring and prevention of drug interactions or adverse drug reactions, and the provision of drug information and medication counseling.

In one study, the researchers noted an improvement in the inpatient documentation of outpatient medications, a reduction in inappropriate discontinuation of outpatient medications, and an increase in ARV prescription accuracy for inpatients.Citation40 Another study examined the benefits of pharmacists on the inpatient service and reported a substantial reduction in the length of time taken to correct an ARV error.Citation38 Conversely, in the only study that examined the effect of a pharmacist’s interventions (see Methods for definition), the reduction in the number of drug interactions between patients whose physician received only their medication list was no different from those whose physician received both the medication list and the pharmacist’s drug interaction notification and management suggestions.Citation35

Discussion

In this systematic review, we evaluated the impact of HIV pharmacists on HIV clinical outcomes, health utilization measures, ARV modifications, and other descriptive variables. In all but one study,Citation18 the involvement of an HIV pharmacist in patient care was associated with clinically and statistically significant improvements in ARV adherence. The majority of reviewed studies also indicated that HIV pharmacist’s care was associated with greater viral load suppression. Evidence of any influence of pharmacists on immunologic outcomes was unclear and attenuated, which may have been due to lack of reporting of CD4+ cell count in many studies, insufficient duration of follow-up to observe substantial changes, the lack of an effect, or the more erratic nature of this outcome measure.

Several study-related factors limited the depth of our review. The most crucial limitation of several studies was the lack of reporting and/or adjustment for baseline demographics and confounders. The absence of reporting of clinical outcomes data in many studies and methodological constraints, such as reporting adherence as dichotomous or categorical variables or other methods, precluded a meta-analysis. Other common limitations included small sample size, short duration of study follow-up, incomplete description of the pharmacist’s role or the complexity of multicomponent interventions, and the use of unconventional methods of adherence calculation. Lastly, as with any systematic review, there is the potential for positive publication bias influencing the aggregate results.

The reviewed studies provide a broad spectrum of HIV pharmacist activities. It is noteworthy that the majority of the reviewed studies were conducted in HIV ambulatory care or inpatient medical center settings. HIV pharmacists practicing in community pharmacies are increasingly called upon to provide ARV adherence training, patient education, and drug information, yet outcome data from such activities are not well-represented in the literature. This may be due to the under-recognized value of these services or the challenges associated with gaining combined access to laboratory medical record and community pharmacy data.

We found a plethora of descriptive studies on ARV-related errors identified and resolved by the pharmacist and the degree of acceptance of pharmacist-related activities, as well as observational studies on the consistent evidence of a positive impact of HIV clinical pharmacists on ARV adherence. Therefore, future mixed methods research, including qualitative and quantitative studies should examine the pharmacist–patient relationship, focus on determining crucial pharmacist functions which have the most impact on adherence, and test these findings in randomized controlled trials with large sample sizes. Additionally, studies should examine cost-effectiveness of pharmacists (including cost savings associated with improvements in clinical markers, as well as other outcomes, such as reductions in extraneous physician visits, emergency room visits, length of hospitalization, medication errors, etc). Further research should also expand to include HIV pharmacist responsibilities that are beyond the “traditional” functions (ie, assessment of ARV accuracy, identification of drug interactions, adherence counseling, patient/provider education, etc). These roles may include the involvement of pharmacists in conducting clinical trials, performance of motivational interviewing, interpretation of drug resistance tests and prescription of ARVs, methods of tailoring adherence-enhancing tools based on individual reasons for nonadherence, and impact on HIV prevention (eg, through offering pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis).

It is evident in this review that research on the impact of pharmacists in HIV clinical care has evolved since the first reports in 1992. This progression includes the use of more sophisticated study designs and more complex research questions. Continued research on HIV pharmacists’ impact on the clinical care of HIV-positive individuals is underway. In ClinicalTrials.gov and the US National Institute of Health Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools database there are currently several ongoing studies examining the role of pharmacists in HIV clinical care. Four of these studies pertain to HIV prevention by assessing and expanding the pharmacist’s role in services related to intravenous drug users purchasing syringes.Citation42–Citation45 Another project is assessing factors related to the receipt of pharmacist-provided adherence counseling and the impact of a counseling session based on the information–motivation–behavioral skills modelCitation46,Citation47 on HIV treatment outcomes.Citation49 A randomized controlled trial is examining the impact of pharmacist care on ARV adherence.Citation49 Lastly, economic outcomes of an intervention comparing methods of offering pharmacist services are also under study.Citation50

Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review provides support for the positive association between HIV pharmacist activities and improvements in ARV adherence and viral load suppression. HIV pharmacist functions were related to reductions in hospitalization, physician office visits, number of hospital days, visits to the emergency department, pill burden, and inappropriate discontinuation of outpatient medications; as well as improvements in inpatient documentation of home medications and accuracy of ARV dosing. A high percentage of pharmacists’ recommendations were accepted by the physician or the health care team and the majority of the pharmacist’s functions involved ARV dosing, detection of drug interactions or adverse drug reactions, provision of drug information, ARV adherence counseling, and instructing on the use of adherence-enhancing tools. This systematic review provides further evidence that, with the growing number of HIV-positive individuals worldwide, the increasing intricacies of HIV treatment options, and the shortage of physicians in resource limited settings, clinical pharmacists trained in HIV pharmacotherapy are invaluable resources and are essential members of the HIV multidisciplinary care team.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gloria Won for her assistance with the search strategies, conducting the electronic search, and creating our preliminary EndNote library. The project described was supported by NIH award numbers F32MH086323, K23MH087218, and K24MH087220. Jennifer Cocohoba received a one-time investigator initiated research grant from Gilead Sciences in 2009.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interests in this work.

References

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC)Pneumocystis pneumonia – Los AngelesMMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep198130212502526265753

- CorelliRLGuglielmoBJKapusnik-UnerJEMcMasterJRGreenblattRMMedication usage patterns in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a comparison of patient-reported medication usage with medical chart reviewDICP19912512137413781815436

- CrawfordNSOrganizing pharmacists to help fight AIDSAm Pharm1991NS31344472028911

- McKnightPTViscontiJAGowerREParaMFZidovudine: counseling strategies and ComplianceAm Pharm1991311038431957797

- WeingartenCMFreelandBPharmacist participation on an HIV resource teamAm J Health Syst Pharm19955212128212847656115

- FoisyMMTsengABlaikieNPharmacists’ provision of continuity of care to patients with human immunodeficiency virus infectionAm J Health Syst Pharm1996539101310178744462

- HorbergMAHurleyLBTownerWJWITHDRAWN: Determination of optimized multidisciplinary care team for maximal antiretroviral therapy adherenceJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr1302012 [Epub ahead of print]

- LefebvreCManheimerEGlanvilleJSearching for studiesHigginsJPTGreenSCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (Updated March 2011)The Cochrane Collaboration2011

- ReevesBCDeeksJJHigginsJPTWellsGAIncluding non-randomized studiesHigginsJPTGreenSCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Version 5.0.1)The Cochrane Collaboration2008

- OstropNJGillMJAntiretroviral medication adherence and persistence with respect to adherence tool usageAIDS Patient Care STDs200014735135810935052

- McPherson-BakerSMalowRMPenedoFJonesDLSchneidermanNKlimasNGEnhancing adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy in non-adherent HIV-positive menAIDS Care200012439940411091772

- MathewsWCMar-TangMBallardCPrevalence, predictors, and outcomes of early adherence after starting or changing antiretroviral therapyAIDS Patient Care STDs200216415717212015870

- SmithSRRubleinJCMarcusCBrockTPChesneyMAA medication self-management program to improve adherence to HIV therapy regimensPatient Educ Couns200350218719912781934

- CastilloEPalepuABeardsellAOutpatient pharmacy care and HIV viral load response among patients on HAARTAIDS Care200416444645715203413

- LevyRWRaynerCRFairleyCKfor Melbourne Adherence GroupMultidisciplinary HIV adherence intervention: a randomized studyAIDS Patient Care STDs2004181272873515659884

- GrossRZhangYGrossbergRMedication refill logistics and refill adherence in HIVPharmaco epidemiol Drug Saf20051411789793

- RathbunRCFarmerKCStephensJRLockhartSMImpact of an adherence clinic on behavioral outcomes and virologic response in treatment of HIV infection: a prospective, randomized, controlled pilot studyClin Ther200527219920915811483

- FrickPTapiaKGrantPNovotnyMKerzeeJThe effect of a multidisciplinary program on HAART adherenceAIDS Patient Care STDs200620751152416839250

- VisnegarwalaFRodriguez-BarradassMCGravissEACaprioMNykyforchynMLaufmanLCommunity outreach with weekly delivery of anti-retroviral drugs compared to cognitive-behavioural health care team-based approach to improve adherence among indigent women newly starting HAARTAIDS Care200618433233816809110

- MarchKMakMLouieSGEffects of pharmacists’ interventions on patient outcomes in an HIV primary care clinicAm J Health Syst Pharm200764242574257818056946

- HorbergMAHurleyLBSilverbergMJKinsmanCJQuesenberryCPEffect of clinical pharmacists on utilization of and clinical response to antiretroviral therapyJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200744553153917224844

- HirschJDRosenquistABestBMMillerTAGilmerTPEvaluation of the first year of a pilot program in community pharmacy: HIV/AIDS medication therapy management for Medi-Cal beneficiariesJ Manag Care Pharm2009151324119125548

- PirkleCMBoileauCNguyenVKImpact of a modified directly administered antiretroviral treatment intervention on virological outcome in HIV-infected patients treated in Burkina Faso and MaliHIV Med200910315215619245536

- KrummenacherICavassiniMBugnonOSpirigRSchneiderMPfor Swiss HIV Cohort StudyAntiretroviral adherence program in HIV patients: a feasibility study in the Swiss HIV Cohort StudyPharm World Sci2010326776786 Epub September 23, 201020862544

- MaAChenDMChauFMSaberiPImproving adherence and clinical outcomes through an HIV pharmacist’s interventionsAIDS Care201022101189119420640958

- HirschJDGonzalesMRosenquistAMillerTAGilmerTPBestBMAntiretroviral therapy adherence, medication use, and health care costs during 3 years of a community pharmacy medication therapy management program for Medi-Cal beneficiaries with HIV/AIDSJournal Manag Care Pharm2011173213223

- KrummenacherICavassiniMBugnonOSchneiderMPAn interdisciplinary HIV-adherence program combining motivational interviewing and electronic antiretroviral drug monitoringAIDS Care201123555056121271406

- HendersonKCHindmanJJohnsonSCValuckRJKiserJJAssessing the effectiveness of pharmacy-based adherence interventions on antiretroviral adherence in persons with HIVAIDS Patient Care STDs2011254221228 Epub Feburary 16, 201121323566

- WaljiNBeardsellABrownGPharmacists’ activities in monitoring zidovudine therapy in an AIDS clinicCan J Hosp Pharm1992451293210117360

- GeletkoSMSegarraMCopelandDATeagueACPharmaceutical care for hospitalized HIV-infected patients compared to infectious diseases consult patients without HIV infectionBMJ Pharmacotherapy1996214557

- BozekPSPerdueBEBar-DinMWeidlePJEffect of pharmacist interventions on medication use and cost in hospitalized patients with or without HIV infectionAm J Health Syst Pharm19985511115111559626378

- GareyKWTeichnerPPharmacist intervention program for hospitalized patients with HIV infectionAm J Health Syst Pharm200057242283228411146973

- GeletkoSMPoulakosMNPharmaceutical services in an HIV clinicAm J Health Syst Pharm200259870971311977854

- Segarra-NewnhamMPreventing medication errors with a pharmacy admission note for HIV-positive patientsHosp Pharm20023713437

- De MaatMMRDe BoerAKoksCHWEvaluation of clinical pharmacist interventions on drug interactions in outpatient pharmaceutical HIV-careJ Clin Pharm Ther200429212113015068400

- FoisyMMAkaiPSPharmaceutical care for HIV patients on directly observed therapyAnn Pharmacother2004384550556 Epub Feburary 27, 200414990778

- SterlingESRomanelliFMartinCAHovenADSmithKMImpact of a pharmacy-initiated HIV admission note on medication errors within an academic hospitalHosp Pharm20054010874881

- HeelonMSkiestDTeresoGEffect of a clinical pharmacist’s interventions on duration of antiretroviral-related errors in hospitalized patientsAm J Health Syst Pharm200764192064206817893418

- PastakiaSDCorbettAHRaaschRHNapravnikSCorrellTAFrequency of HIV-related medication errors and associated risk factors in hospitalized patientsAnn Pharmacother200842449149718349307

- HoraceAPhilipsMIdentification and prevention of antiretroviral medication errors at an academic medical centerHosp Pharm20104512927933

- CarceleroETusetMMartinMinterventions by the clinical pharmacist in hospitalized HIV-infected patientsHIV Med201112849449910.1111/j.1468–1293.2011.00915.x Epub March 13, 201121395966

- CasePLFeasibility of pharmacy-based HIV intervention among IDUs: 2 New England citiesNational Institutes of Health Project Reporter (project number: R21DA025010)2010 Available from: BioMedLib.com

- FullerCMPharmacy referral intervention: IDU access to servicesNational Institutes of Health Project Reporter (project number: R01DA022144)2010 Available from: BioMedLib.com

- LatkinCAFeasibility of pharmacy-based HIV interventions among IDUs: IndiaNational Institutes of Health Project Reporter (project number: R21DA024971)2010 Available from: BioMedLib.com

- PielemeierNFeasibility of pharmacy-based HIV interventions among IDUs: Ha Giang, VietnamNational Institutes of Health Project Reporter (project number: R21DA024986)2010 Available from: BioMedLib.com

- FisherJDFisherWAMisovichSJKimbleDLMalloyTEChanging AIDS risk behavior: effects of an intervention emphasizing AIDS risk reduction information, motivation, and behavioral skills in a college student populationHealth Psychol19961521141238681919

- AmicoKRToro-AlfonsoJFisherJDAn empirical test of the information, motivation and behavioral skills model of antiretroviral therapy adherenceAIDS Care200517666167316036253

- CocohobaJMBeyond pill-counting: effect of pharmacist counseling on antiretroviral adherenceNational Institutes of Health Project Reporter (project number: K23MH087218)2011 Available from: BioMedLib.com

- Hospital de Clinicas de Porto Alegre; Federal University of Rio Grande do SulEvaluation of effectiveness of pharmaceutical care on the adherence of HIV-positive patients to antiretroviral therapy (PC-HIV)ClinicalTrialsgov [website on the internet]Bethesda, MDUS National Library of Medicine2009 Available from: clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00959361. NLM identifier: NCT00959361

- WilsonIBNudging doctors to collaborate with pharmacists to improve medication adherenceNational Institutes of Health Project Reporter (project number: RC4AG039072)2010 Available from: BioMedLib.com