Abstract

Purpose

Studies assessing quality of life (QOL) in palliative care settings are still scarce. We assessed the QOL score and pain severity in advanced breast cancer patients at the National Cancer Hospital in Indonesia and associations between QOL domains with QOL and pain scores.

Materials and Methods

A total of 160 patients who met the study inclusion criteria (female, >18 years old, diagnosed with stage III or IV breast cancer) answered the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QOL questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL) and the visual analogue scale (VAS) tool for pain severity, prior to palliative oncology treatment. Additionally, several sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were collected. Linear regression models, adjusted for age, the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score, and specific QOL domains were used to explore the associations between the global QOL and VAS scores with the different QOL domains.

Results

The patients had a mean age of 50 years (range: 29–76). The overall score for QOL and score for VAS was (mean ± SD) 78.02 ± 15.34 and 2.1 ± 2.4, respectively. The analysis demonstrated that the domains of emotional functioning (effect estimate: 0.25; 95% CI: 0.14 to 0.37), fatigue (−0.21; −0.33 to −0.09), pain (−0.13; −0.25 to −0.01), insomnia (−0.25; −0.37 to −0.13), and appetite loss (−0.13; −0.25 to −0.008) were associated with the QOL score. Only the KPS score (−0.28; −0.46 to −0.11) was associated with the VAS score.

Conclusion

Our study showed high QOL and low VAS scores in advanced breast cancer patients prior to palliative oncology treatment. Several QOL domains (emotional functioning, fatigue, pain, insomnia, and appetite loss) were associated with QOL and the KPS was associated with the pain score. Therefore, these specific QOL domains should be given priority in improving QOL in this patient group.

Introduction

Breast cancer remains a major public health problem around the world. Approximately 2.2 million women worldwide develop this disease, and breast cancer is the most common cancer entity.Citation1 In Indonesia, it was estimated that in 2020 65,858 incidents of breast cancer cases and 22,430 annual deaths due to breast cancer occurred.Citation2 Advanced breast cancer patients often experience long-term chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment and accumulation of psychological distress, chronic pain, and fatigue, which leads to impaired quality of life (QOL).Citation3–Citation5

QOL is a multidimensional concept that considers patients’ subjective assessment of their situation at a specific time.Citation6 Despite its subjective aspect, QOL is considered valid, reliable, and responsive to capturing important clinical changes.Citation7,Citation8 Moreover, QOL is an important patient-reported outcome that provides insight into patient’s disease burden,Citation9,Citation10 helpful in patient empowerment, and useful in the interpretation of clinical outcomes and treatment decision-making.Citation9

Pain is one of the most common reported symptoms in cancer patients and occurs as part of the disease process or a side effect of cancer treatment. It represents a problem for most breast cancer patients and negatively affects the QOL.Citation6,Citation7 A systematic review and meta-analysis, which assessed pain prevalence of adult cancer patients globally, stated that pain is prevalent in 39.3% of cases after curative treatment, 55.0% during cancer treatment, and 66.4% in advanced disease stages.Citation8 It is important to assess pain, as untreated chronic pain often worsens other QOL aspects (eg fatigue, nausea, constipation, sleep disturbances, and depression). Symptom control is an effective way to improve QOL of all cancer patients, but it is mostly important for advanced cancer patients who no longer respond well to curative or life-prolonging treatments.Citation11,Citation12

Despite growing evidence regarding the positive impact of QOL assessment and pain severity in advanced cancer, most QOL research was conducted in patients from developed countries, which have different needs and characteristics compared to patients from developing countries.Citation9 Moreover, studies showed that scores of QOL/QOL domains varied between countriesCitation14–Citation16 and there is a need for further research in patient-reported outcomes, such as QOL and pain severity, when planning patients’ individual cancer management plans. Therefore, this study aims to assess QOL score and pain severity in advanced breast cancer patients prior to palliative oncology treatment at the National Cancer Hospital in Indonesia and identify which QOL domains (eg functional and symptom scales) are associated with the QOL score and pain severity.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Patients at the oncology unit of the “Dharmais” cancer hospital in Jakarta, Indonesia were invited to participate in this cross-sectional study between January and February 2020. To enter the study, patients had to meet the study inclusion criteria: female; aged > 18 years; diagnosed with advanced breast cancer; had no difficulty in communicating during the data collection without the help of a caregiver; and were scheduled to start palliative oncology treatment. Advanced breast cancer was defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer as stage III or IV breast cancerCitation10 and where no further curative treatment options were planned.Citation17 The primary palliative oncology treatments were chemotherapy and hormonal therapy, while radiotherapy and surgery were used if required to reduce symptoms, but not for curative purposes.Citation11 Patients with psychological disorders were excluded from the study.

The data collection was conducted following the admissions of patients to the oncology unit’s nursing station before their consultation appointment with the oncologist. After the consultation, patients were referred to receive further palliative oncology treatment. While we did not have direct access to medical records, the hospital nurses facilitated the patients’ screening process for potential study inclusion. We explained the purposes of the study to the invited participants before starting the interview. If the individual refused to participate, we documented the reasons for declining participation. All participants provided written informed consent that was in line with the Declaration of Helsinki.Citation18 The Ethics Committee of the “Dharmais” Cancer Hospital approved the study protocol (136/KEPK/VII/2019).

Study Instruments

Outcome variables (QOL score and pain severity) and QOL domains (physical and emotional functioning, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, and constipation) were self-reported by patients.Citation19 For assessing the global QOL and QOL domains, the Indonesian version of the EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 15-Palliative Care (EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL) was used, with the permission from the EORTC Quality of Life Group. The EORTC QLQ-C15 PAL is a 15-item validated and reliable tool for QOL assessment.Citation20 It is a short version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 core questionnaire,Citation21 of which the Indonesian version was validated.Citation22 The EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL consists of one global QOL item (question 15), in addition to several functional and symptom scales. The functional scales comprise questions regarding physical functioning (questions 1–3) and emotional functioning (questions 13 and 14). The symptom questions consist of a fatigue scale (questions 7 and 11), a pain scale (questions 5 and 12), and single items for the nausea and vomiting scale (question 9), dyspnea (question 4), insomnia (question 6), appetite loss (question 8), and constipation (question 10). For questions 1–14, patients graded their response using a 4-point Likert scale: 1) not at all, 2) a little, 3) quite a bit, and 4) very much. For question 15, which assessed global QOL, a 7-point numerical scale with a score of 1 (very poor overall QOL) to 7 (excellent overall QOL) was used. All QOL/QOL domain responses were related to how the patient was feeling during the past week before the hospital consultation.

Pain severity was assessed using the visual analogue scale (VAS) method on a 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain) scale. The VAS provides responses that are reliable, valid, and mostly preferred by patients.Citation12 The VAS score represents the current pain severity status of patients during data collection.

We also collected sociodemographic characteristics, including age, place of residence, education, marital status, ethnic group, religion, and clinical characteristics (body mass index (BMI), the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS), metastasis status, and history of cancer treatments (surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy)). The KPS assesses the functional capacity of patients related to daily activities on a scale from 0 to 100, with 0% (describing death) to 100% (representing normal activity).Citation13

Statistical Analysis

For continuous sociodemographic and clinical data, results were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or interquartile range (IQR) and median, depending on data distribution, while categorical variables were described with frequencies and percentages. Normal distribution was tested using a histogram plot. The scoring of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL domains was performed according to the EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual.Citation14 The scores for the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL abbreviated scales (physical functioning, emotional functioning, nausea and vomiting, and fatigue) were estimated using the addendum to the EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual: Scoring of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL.Citation15 The EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL scoring principle was to calculate the mean values for all the items (the raw score), which was then linearly transformed to yield scores from 0 to 100. While a high score for the global QOL or the functional scales shows a better QOL or level of functioning, a high VAS score describes an unfavourable level of experienced pain. All items of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL and VAS are described as means (SDs).

The nonparametric Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to assess the difference in several sociodemographic and clinical variables (eg BMI, place of residence, education, marital status, and age groups) on QOL/QOL domain scores. The Spearman rank correlation assessed the correlation between QOL score and specific QOL domains.

Linear regression models were used to investigate which QOL domains were associated with the global QOL item and the VAS score. First, the linear regression model was used to assess the association between global QOL and separately for each of the specific QOL domains (eg physical and emotional functioning, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, and constipation) adjusted for age and the KPS score (Model I). Second, the association between the global QOL and the different QOL domain scores was examined, adjusting for all specific QOL domains and additionally for age and the KPS score (Model II). We used the same two-step analysis approach for the VAS score. We standardized all the regression coefficients and tested for multicollinearity in the multivariable analysis to explore the degree of correlation between independent variables included in the models. A recommendation of the variance inflation factors greater than 10 was used for identifying potential multicollinearity.Citation25 Data were analysed with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient Characteristics

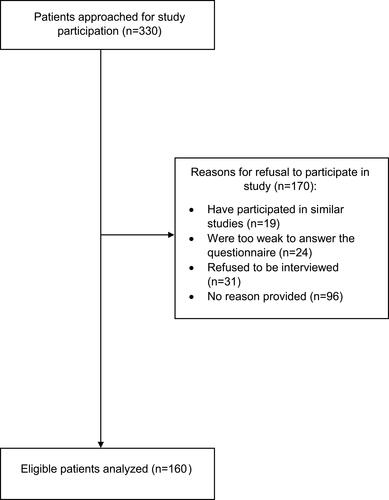

Of 330 eligible advanced breast cancer patients approached, 160 patients completed the questionnaire and were included in the analysis. Each assessment took approximately 12 minutes per patient. The most common reasons for declining to participate were refusal to be interviewed (n = 31) and being too weak to answer the questionnaire (n = 24) ().

In this study, the mean age was 50 years (range: 29–76), 72.5% of patients lived in urban areas, 71.8% had a low educational level, and 81.9% were married (). While the majority reported having received previous breast cancer treatments (surgery (96.9%) and/or chemotherapy (63.1%)), only 37.5% of patients had experienced radiation therapy. The mean KPS score was 80.7 ± 6.8, and on average, patients were overweight with a BMI of 25.9 ± 4.7 kg/m2 ().

Table 1 Sociodemographic Characteristics of 160 Advanced Breast Cancer Patients

Quality of Life Assessment

The EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL mean scores for global QOL (78.02 ± 15.34), physical and emotional functioning were high, at 75 or above (). The score of most symptom scales in our study were reportedly good (range: 3.33 ± 11.79 to 8.54 ± 23.93), which describes that breast cancer patients had better symptoms experience. However, for fatigue, pain, and insomnia, the score was reportedly worse (range: 17.50 ± 33.11 to 24.01 ± 27.47 (). There were no differences in the QOL/QOL domain scores of advanced breast cancer across most sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (eg age groups, BMI with a cut-off point 25 kg/m2, place of residence, education, and marital status) (Supplement Table 1). As expected, physical and emotional functioning (functional scales) was positively correlated with the QOL score and all symptom scales were negatively correlated with the QOL score (Supplement Table 2).

Table 2 Mean Quality of Life, Functional Scale, and Symptom Scale Scores

In a linear regression Model I, most of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL domains, except dyspnea, were associated with the global QOL score after adjustment for age and the KPS score (). However, in Model II, only some of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL domains remained associated with the global QOL score. A positive association was found for emotional functioning (effect estimate: 0.25; 95% CI: 0.14 to 0.37) and a negative association was found for fatigue (−0.21; −0.33 to −0.09), pain (−0.13; −0.25 to −0.01), insomnia (−0.25; −0.37 to −0.13), and appetite loss (−0.13; −0.25 to −0.008) ().

Table 3 Linear Regression Analyses of Associations for Quality of Life Score

Pain Severity (VAS)

The mean score for VAS was low (2.1 ± 2.4), which indicated reasonable control of pain (). In Model I, most of the domains, except nausea and dyspnea, were associated with the VAS score. However, only the KPS score remained negatively associated with the VAS score in Model II (effect estimate: −0.28; 95% CI: −0.46 to −0.11) ().

Table 4 Linear Regression Analyses of Associations for Pain Severity (VAS)

Discussion

This study assessed the QOL score and pain severity in Indonesian advanced breast cancer patients prior to palliative oncology treatment. Several QOL domains (emotional functioning, fatigue, pain, insomnia, and appetite loss) were associated with the global QOL score. Only the KPS score was associated with the VAS score among the assessed variables. Interestingly, our findings showed that the QOL was higher and VAS score was lower in this study than in previous studies in a similar context.

Quality of Life Among Cancer Patients

In general, QOL and QOL domain scores in advanced breast cancer individuals are expectedly poor.Citation26 Our study supported this finding, but our results showed a higher score of global QOL and QOL domains as compared to previous studies in breast cancer patients.Citation16,Citation17 There are several possible explanations for our findings. The first key component is the methodological aspect. In this study, some participants who were too weak to answer the questionnaire refused to participate, resulting in missing information from those who were in special need of particular treatments and contributing to non-response bias.Citation18 The second explanation for the high score of QOL is possible unawareness of the disease’s prognosis as per discussion with oncologists in the hospital (personal communication). As our study subjects were patients who were referred to the palliative oncology department, the planned treatment could be assumed for a curative purpose, instead of palliative, resulting in better scores for QOL/QOL domains.Citation13 The palliative situation was possibly not directly communicated or not clearly explained to patients due to fears of caregivers and relatives that patients may lose hope.Citation19 The inadequate ratio between doctors and patients in most developing countries often leads to insufficient consultation timeCitation13 and poor patient-doctor communication,Citation20 resulting in unclear information on the accurate prognosis of the patient.Citation21 However, communicating and confirming the accurate prognosis is important for advanced cancer patients as it relates to cancer treatment plans, matching with their individual/cultural preferences and values.Citation13 Consequently, this communication process is highly appreciated and valued by patients, since including their perspective in the cancer treatment plan provides them with a sense of dignity and confidence.

Last, cultural aspects play a key role in the QOL of advanced cancer patients. For example, caring for a family member is part of Indonesian and Asian culture. When a household member is diagnosed with cancer, other family members will provide support, take care of the patient, and act as caregivers.Citation22,Citation23 Caring for a family member with cancer is considered an obligation and responsibility in Asian culture.Citation24 Consequently, strong family bonds and good communication between patients and caregivers develop during the disease process and its treatment.Citation23,Citation25 This social and psychological support positively influences patients’ QOL/QOL domains.Citation23,Citation26 In contrast, patients who were unsupported by family members were reported to have a high score of anxiety/depression and poor QOL.Citation27 Also, spirituality and religiosity are key components of Indonesian culture and influence the motivation to care for cancer patients.Citation27 For instance, studies reported that spiritual and religious practices in Indonesia and most developing countries acted as a positive factor for providing comfort and support for a sick family memberCitation26,Citation28 and positively affected cancer patients’ ability to cope.Citation29 Since most of our patients were religious individuals (around 90%), this aspect adds to the explanation of our findings. As various individual and cultural factors influence the QOL/QOL domains of advanced cancer patients, it is necessary to acknowledge the perspectives of patients and caregivers during cancer treatment management.

Pain Severity

Pain is prevalent among advanced cancer patients, but our study sample surprisingly had lower VAS scores or better pain experiences as compared to previous studies.Citation30–Citation32 Hospital physicians confirmed that pain was rarely reported in the setting (personal communication, Supplement Table 3). Possible explanations could be several non-pharmacological reasons, such as psychological, sociocultural, behavioral, and affective aspects.Citation32 Evidence indicates that the role of psychological factors and behavior (eg coping and emotional distress) should be considered in both non-cancer- and cancer-related pain.Citation33 Consequently, the importance of psychological and behavioral treatments was emphasized as non-pharmacologic options that are recommended, together with pharmacologic interventions, to achieve effective pain management. For example, an intervention targeting the development of adaptive coping strategies may enhance a patient’s feeling of confidence in managing his or her pain, which in turn may be associated with a reduction in pain intensity or severity and with a reduction in emotional distress and consequent increase in QOL.Citation34 Therefore, it is important to recognize the complex and multidimensional nature of patients’ experiences with cancer-related pain and also their response to this pain.

Our findings did not show an influence of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics on QOL and pain severity. This was possibly due to a homogeneous patient group, in addition to missing those patients in poor condition, and the convenience sampling method used. However, previous evidence has indicated that QOL is influenced by various individual aspects (eg age, sex, educational level, marital status, number of children, living situation, and diagnoses).Citation16,Citation17,Citation32 Moreover, several cultural aspects (eg spirituality/religiosity) play an important role in personal motivation, symptom amplification, and value preferences.Citation35 Consequently, patients’ symptoms and functional status, general health perception, and global QOL can presumably be influenced by all these factors.Citation6 As shown by our models, several symptom scales of QOL domains affect advanced breast cancer patients’ QOL. Similarly, a Bahraini study showed that the most distressing symptoms on the symptom scales were fatigue, sleep disturbance, and pain which were negatively associated with QOL score.Citation17 Therefore, we believe if physicians give more attention to cancer related symptoms such as fatigue, pain, and insomnia during patients’ counseling in this setting, QOL improvement can be achieved in this patients’ group.

The QOL of advanced cancer patients is a complex situation, incorporating dynamic multidimensional circumstances and requires appropriate strategies, such as comprehensive oncology services or palliative care, which will maintain/increase QOL and facilitate efficient allocation of medical resources. It is evident that providing PC to patients regardless of their cancer stage is highly recommended.Citation36 A systematic review indicated that advanced cancer patients who received PC had better QOL and symptoms than those in conventional cancer treatment.Citation30 However, our study assessed QOL and pain severity in advanced breast cancer patients prior to palliative oncology treatment; therefore, an analysis of follow-up data is needed to explore this hypothesis.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study contributes to a better understanding of QOL assessment and pain severity in Indonesia prior to palliative oncology treatment at the National Cancer Hospital where standardized palliative oncology had been implemented and practiced. The questionnaire was standardized and thus comparable to a large number of studies conducted elsewhere in the world.

There are also several limitations. The self-reported approach has constraints, such as the information about the metastatic disease might have introduced a reporting bias since patients sometimes neglect unwanted information. The convenience sampling might result in an underpowered analysis, which explains the absence of differences in sub-group analyses (eg urban/rural or married/single). We were unable to obtain detailed medical records. However, since hospital nurses facilitated the screening process for patients’ eligibility criteria, we did assume considerable reliability of the medical information. Another limitation is the low participation of patients in a poor condition, leading to under-representation of lower QOL and higher VAS scores. This is a common problem in QOL and pain studies. In spite of that, our study was proficient enough to describe QOL assessment and pain severity within the population composition as described.

Conclusion

Our study, which assessed the QOL and pain severity of advanced breast cancer patients` cohort before palliative oncology treatment, showed better QOL and VAS scores in Indonesia compared to previous studies. Also, our findings indicated that QOL score were associated with several QOL domains (emotional functioning, fatigue, pain, insomnia, and appetite loss) of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL, while the VAS score was associated with KPS. Therefore, these specific QOL domains should be given proper attention by treating oncologists before palliative oncology treatment in this patient group.

Abbreviations

BMI, body mass index; EORTC, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; QLQ-C15-PAL, validated quality of life questionnaire for advanced cancer stage; IQR, interquartile range; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status; QOL, quality of life; SD, standard deviation; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the “Dharmais” Cancer Hospital (study protocol number 136/KEPK/VII/2019) and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed the written informed consent before participating in the study.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the revision to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

DG was supported by the Indonesia Lecturer Scholarship (BUDI) from the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP), Ministry of Finance, Republic of Indonesia. We acknowledge the financial support of the Open Access Publication Fund of the Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg. We thank all patients who voluntarily participated in this study and the hospital staffs at the study site for their support with patient recruitment process. We acknowledge Fitriyani Sukesmi and Meilinda Ariyantii for their assistance with data collection process. We are grateful to Dr. dr. Denni Joko Purwanto, SpB(K)Onk, M.M, dr. Bob Andinata, Sp.B(K)Onk, dr. Edi S. Tehuteru, Sp.A(K), MHA, IBCLC and academic staffs Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Indonesia (Agustin Kusumayati, Ph.D, Prof. Dr. Sabarinah Prasetyo, Prof. Asri C. Adisasmita, Ph.D, Dr. Tri Yunis Miko Wahyono, Prof. Dr. Ratna Djuwita, and Adang Bachtiar, Sc.D) for their support on facilitating the data collection process. We thank apl. Prof. Dr. Andreas Wienke for his valuable comments on the statistical aspects.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- IARC. Globocan 2020: estimated cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence worldwide in 2020. Cancer fact sheet: breast. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/20-Breast-fact-sheet.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2021.

- IARC. Globocan 2020: estimated cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence worldwide in 2020. Indonesia fact sheets. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/360-indonesia-fact-sheets.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2020.

- Aboshaiqah A, Al-Saedi TSB, Abu-Al-Ruyhaylah MMM, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with care among palliative cancer patients in Saudi Arabia. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14(6):621–627. doi:10.1017/S1478951516000432

- Astrup GL, Hofso K, Bjordal K, et al. Patient factors and quality of life outcomes differ among four subgroups of oncology patients based on symptom occurrence. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(3):462–470. doi:10.1080/0284186X.2016.1273546

- Li Q, Xu Y, Zhou H, Loke AY. Factors influencing the health-related quality of life of Chinese advanced cancer patients and their spousal caregivers: a cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:72. doi:10.1186/s12904-016-0142-3

- Krok JL, Baker TA, McMillan SC. Age differences in the presence of pain and psychological distress in younger and older cancer patients. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2013;15(2):107–113. doi:10.1097/NJH.0b013e31826bfb63

- Nishiura M, Tamura A, Nagai H, Matsushima E. Assessment of sleep disturbance in lung cancer patients: relationship between sleep disturbance and pain, fatigue, quality of life, and psychological distress. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(3):575–581. doi:10.1017/S1478951513001119

- Snyder CF, Blackford AL, Okuyama T, et al. Using the EORTC-QLQ-C30 in clinical practice for patient management: identifying scores requiring a clinician’s attention. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(10):2685–2691. doi:10.1007/s11136-013-0387-8

- Chen CH, Kuo SC, Tang ST. Current status of accurate prognostic awareness in advanced/terminally ill cancer patients: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Palliat Med. 2017;31(5):406–418. doi:10.1177/0269216316663976

- Byrd DR, Carducci MA, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York: Springer; 2018.

- Ministry of Health the Republic of Indonesia. Pedoman nasional pelayanan kedokteran tata laksana kanker payudara (National guidelines of breast cancer treatments) No. HK.01.07/MENKES/414/2018. Jakarta, Indonesia: Ministry of Health, the Republic of Indonesia; 2018.

- Klimek L, Bergmann KC, Biedermann T, et al. Visual analogue scales (VAS): measuring instruments for the documentation of symptoms and therapy monitoring in cases of allergic rhinitis in everyday health care. Allergo J Int. 2017;26(1):16–24.

- Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: MacLeod CM, editor. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. New York: Columbia University Press; 1949:196.

- Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, et al. The EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. 3rd ed. Brussels, Belgium: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2001.

- Groenvold M, Petersen M; Group obotEQoL. Addendum to the EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual: scoring of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL. Brussels, Belgium: EORTC Quality of Life Unit; 2006.

- Imran M, Al-Wassia R, Alkhayyat SS, Baig M, Al-Saati BA. Assessment of quality of life (QoL) in breast cancer patients by using EORTC QLQ-C30 and BR-23 questionnaires: a tertiary care center survey in the western region of Saudi Arabia. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219093. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0219093

- Jassim GA, Whitford DL. Quality of life of Bahraini women with breast cancer: a cross sectional study. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:212. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-13-212

- Rinck GC, van den Bos GA, Kleijnen J, de Haes HJ, Schade E, Veenhof CH. Methodologic issues in effectiveness research on palliative cancer care: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(4):1697–1707. doi:10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1697

- Hancock K, Clayton JM, Parker SM, et al. Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced life-limiting illnesses: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2007;21(6):507–517. doi:10.1177/0269216307080823

- Higginson IJ, Costantini M. Dying with cancer, living well with advanced cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(10):1414–1424. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.02.024

- Claramita M, Utarini A, Soebono H, Van Dalen J, Van der Vleuten C. Doctor-patient communication in a Southeast Asian setting: the conflict between ideal and reality. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2011;16(1):69–80. doi:10.1007/s10459-010-9242-7

- Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273(1):59–65. doi:10.1001/jama.1995.03520250075037

- Effendy C, Vernooij-Dassen M, Setiyarini S, et al. Family caregivers’ involvement in caring for a hospitalized patient with cancer and their quality of life in a country with strong family bonds. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24(5):585–591. doi:10.1002/pon.3701

- Cui J, Fang F, Shen F, et al. Quality of life in patients with advanced cancer at the end of life as measured by the McGill quality of life questionnaire: a survey in China. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(5):893–902. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.02.016

- Kristanti MS, Setiyarini S, Effendy C. Enhancing the quality of life for palliative care cancer patients in Indonesia through family caregivers: a pilot study of basic skills training. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16(1):4. doi:10.1186/s12904-016-0178-4

- Iskandarsyah A, de Klerk C, Suardi DR, Soemitro MP, Sadarjoen SS, Passchier J. Satisfaction with information and its association with illness perception and quality of life in Indonesian breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(11):2999–3007. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-1877-5

- Pokpalagon P, Hanucharurnkul S, McCorkle R, Tongprateep T, Patoomwan A, Viwatwongkasem C. Comparison of care strategies and quality of life of advanced cancer patients from four different palliative care settings. Pac Rim Int J Nurs Res. 2012;16(4):326–342.

- Gayatri D, Efremov L, Kantelhardt EJ, Mikolajczyk R. Quality of life of cancer patients at palliative care units in developing countries: systematic review of the published literature. Qual Life Res. 2021;30:315–343.

- Koenig H, King D, Carson VB. Handbook of Religion and Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

- Haun MW, Estel S, Rucker G, et al. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD011129.

- Wang Y, Shen J, Xu Y. Symptoms and quality of life of advanced cancer patients at home: a cross-sectional study in Shanghai, China. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(6):789–797. doi:10.1007/s00520-010-0884-z

- Hamood R, Hamood H, Merhasin I, Keinan-Boker L. Chronic pain and other symptoms among breast cancer survivors: prevalence, predictors, and effects on quality of life. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;167(1):157–169. doi:10.1007/s10549-017-4485-0

- Hjermstad M, Haugen DF, Bennett MI, Kaasa S. Pain assessment tools in palliative care and cancer. In: Moore RJ, editor. Handbook of Pain and Palliative Care: Biobehavioral Approaches for the Life Course. New York: Springer; 2011.

- Donovan KA, Thompson LMA, Jacobsen PB. Pain, depression and anxiety in cancer. In: Moore RJ, editor. Pain, Depression and Anxiety in Cancer. New York: Springer; 2011.

- Fayers PM. Interpreting quality of life data: population-based reference data for the EORTC QLQ-C30. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(11):1331–1334. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00127-7

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization: definition of palliative care. 2002. Available from: https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Accessed September 12, 2018.