Abstract

Drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) requires prolonged and complex therapy which is associated with several adverse drug reactions (ADR). The burden of ADR can affect the quality of life (QoL) of patients that consists of physical, mental, and social well-being, and influences the beliefs and behaviors of patient related to treatment. This article reviews the burden of ADR and its association with QoL and adherence. We used PubMed to retrieve the relevant original research articles written in English from 2011 to 2021. We combined the following keywords: “tuberculosis,” “Drug-resistant tuberculosis,” “Side Effect,” “Adverse Drug Reactions,” “Adverse Event,” “Quality of Life,” “Adherence,” “Non-adherence,” “Default,” and “Loss to follow-up.” Article selection process was unsystematic. We included 12 relevant main articles and summarized into two main topics, namely, 1) ADR and QoL (3 articles), and 2) ADR and therapy adherence (9 articles). The result showed that patients with ADR tend to have low QoL, even in the end of treatment. Although it was torturing, the presence of ADR does not always result in non-adherence. It is probably because the perception about the benefit of the treatment dominates the perceived barrier. In conclusion, burden of ADR generally tends to degrade QoL of patients and potentially influence the adherence. A comprehensive support from family, community, and healthcare provider is required to help patients in coping with the burden of ADR. Nevertheless, the regimen safety and efficacy improvement are highly needed.

Introduction

Drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) remains a global public health problem. It is defined as a disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria that have been resistant to the standard antimicrobial treatment. In 2019, approximately 465,000 people with TB were resistant to rifampicin or called rifampicin-resistant TB (RR TB), of which 78% were multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB). MDR is a condition when bacteria are resistant to both Isoniazid and Rifampicin as the two most potent antituberculosis drugs. Unlike drug-susceptible tuberculosis (DS-TB) treatment, which only requires first line antituberculosis, RR/MDR-TB treatment requires a combination of second line antituberculosis drugs. Recent WHO recommendation of RR/MDR-TB treatment has categorized antituberculosis agent into 3 groups. Group A consists of bedaquiline, fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin/moxifloxacin), and linezolid. Group B consists of clofazimine and cycloserine/terizidone. Group C consists of ethambutol, delamanid, pyrazinamide, imipenem–cilastatin/meropenem, amikacin, streptomycin, ethionamide/prothionamide, p-aminosalicylic acid. Combination of all drugs from group A and at least one drug from group B is recommended as a standard treatment of long-term regimen, while group C can be administered when main drugs from group A and B cannot be used. Long-term regimen requires 18–24 months of therapy, this is 3–4 times longer than DS-TB therapy which only requires 6 months of therapy. Yet, for patients with certain conditions, the duration can be shortened to 9–12 months or called short-term regimen.Citation1,Citation2

DR-TB therapy is quite challenging owing to prolonged duration, more complex, and more toxic regimens that likely cause adverse drug reactions (ADR).Citation1,Citation2 ADR is a response to a drug that is noxious, unintended, and occurs at doses normally used in man for prophylaxis, diagnosis, or therapy of disease, or for the modification of a physiological function.Citation3 The severity of ADR can be categorized in major (consists of fatal, life-threatening, severe) and minor (consists of mild, moderate) types.Citation4 Several ADR of DR-TB therapy regimens that have been reported included gastrointestinal (GI) disturbances as the most common ADR (induced by p-aminosalicylic acid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, and ethionamide), ototoxicity (aminoglycoside), peripheral neuropathy (isoniazid, cycloserine, ethambutol, ethionamide), psychiatric disorders (cycloserine, fluoroquinolone), QT prolongation (delamanid, bedaquiline, fluoroquinolone), hypothyroidism (p-aminosalicylic acid, ethionamide), dermatologic disorders (pyrazinamide, clofazimine), renal impairment (aminoglycoside), vision problems (ethambutol, linezolid), electrolyte imbalance (aminoglycoside), hepatic dysfunction (all), seizures (cycloserine, isoniazid, fluoroquinolone), Arthralgia (fluoroquinolone, pyrazinamide), dizziness, and headaches.Citation5–Citation12 Some ADR even persist after the therapy ended.Citation4,Citation5,Citation13

ADR are burdensome and interfere with daily life activities and the well-being of patients.Citation14,Citation15 The burden can inflict poor quality of life (QoL), as patients had to spend a lot of energy, time, and resources to deal with their conditions that potentially influenced their beliefs and behaviors related to their treatments.Citation15,Citation16 Finally, it results in increasing the risk of non-adherence that led to unachieved therapy goals and poor treatment outcomes.Citation15

Although many studies about ADR have been published, only a few discussed the impact on the well-being or QoL of patients quantitatively, while many of them focused on the prevalence and ADR types. Given that the QoL is important, it may impact adherence as a critical concern of DR-TB therapy, and both topics should be understood properly. Therefore, the literature review was written to discuss the 1) association between ADR and health-related QoL, and 2) association between ADR and therapy adherence. A comprehensive discussion about ADR, QoL, and adherence in DR-TB patients helps to demonstrate burden of ADR from psychosocial perspective. This review is expected to be the source of information for healthcare providers in understanding the burden of ADR that frequently occur in DR-TB patients.

Materials and Methods

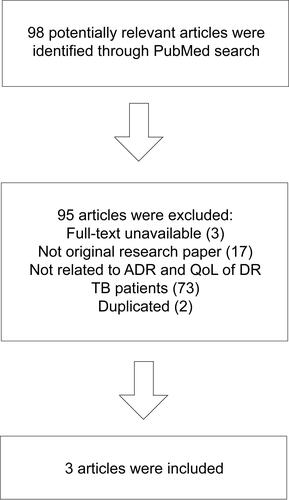

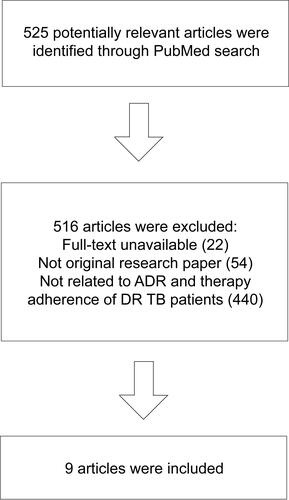

We searched for articles in PubMed with the use of the following keyword combinations to meet the aim of this study: “tuberculosis,” “Drug-resistant tuberculosis,” “Side Effect,” “Adverse Drug Reactions,” “Adverse Event,” “Quality of Life,” “Adherence,” “Non-adherence,” “Default,” and “Loss to follow-up.” We included original research studies written in English from 2011 to 2021. The identification of articles and the selection process were not systematic. The flow of article selection is illustrated in and . Only original research studies with quantitative methods were selected as the main articles. Articles on unrelated topics were excluded. The results were summarized into two main topics, namely, 1) ADR and Health Related-QoL, and 2) ADR and therapy adherence. The search strategy identified 12 quantitative research papers as the main articles.

ADR and Health-Related QoL

QoL is a multidimensional concept that represents the perceived position of an individual regarding physical health, psychological condition, social relationships, personal beliefs, level of independence, and his/her relationship to environment.Citation17 When it corresponds to or affected by the presence of disease or treatment, it is called health-related QoL (HR QoL).Citation18 HR QoL is one healthcare system output that is important to be measured. It is broader than biological functioning and morbidity.Citation19

Some research had proven that tuberculosis and its consequences affected HR-QoL not only due to somatic symptom but also had psychological and social impacts.Citation20–Citation22 Moreover, in DR-TB, long-term therapy and toxic drugs render the implementation of curing processes more difficult.Citation23 A systematic review has reported that the HR-QoL of MDR-TB patients was considerably lower than DS-TB patients, especially in the first six months of therapy.Citation24,Citation25 ADR is one of the predictors of HR-QoL in DR-TB patients in addition to other sociodemographic factors, such as age, family support, sex, education, marital status, and clinically related factors, such as TB history, baseline lung cavity, sickness before diagnosis, positive diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and usage of injectable drugs.Citation22,Citation25–Citation29

The research on this topic remains scarce. Three studies investigated associations of ADR with the patients’ HR-QoL in DR-TB patients (). One of these investigated both DS-TB and DR-TB. Two of the studies indicated associations between ADR and HR-QoL.Citation20,Citation22 A study reported by Sineke used the SF-36 questionnaire to investigate the mental component summary (MCS) and the physical component summary (PCS). DR-TB patients with reported ADR more likely had lower MCS (aRR 2.24 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.53–3.27) and PCS (aRR 1.52 95% CI 1.07–2.18) scores than patients who did not report ADR. The mental score was found to be lower than physical score. This means that physical health recovers faster than mental health.Citation22

Table 1 Quantitative Studies of Association Between ADR and QoL in MDR-TB Patients

ADR during the early month of therapy has reduced HR-QoL substantially. Usage of injectable drugs also contributed to the deterioration of HR-QoL. Patients with injectable drugs were 1.49 times more likely to have low MCS scores than patients with injection-free regimens.Citation22

A study conducted by Valadares et al investigated the association between ADR and QoL in a TB population consisted of DS-TB and DR-TB. Patients who suffered both minor and major ADR had worse QoL than patients with minor ADR only.Citation20

Contradictory results were reported by Sagwa et al that identified no association between QoL and ADR in MDR-TB patients. This finding was reasonable because the subject underwent the final month of treatment or had completed treatment within the last three months.Citation30 Severe side effects frequently suffered in the intensive phase. In the continuation phase there may be several persistent adverse outcomes, such as hearing loss, but it could be tolerated or handled better as therapy progressed, and as the number of medications decreased over time. Therefore, unlike the early phase, the patients in the final month of therapy may have a better QoL.Citation30–Citation32 Despite significant HR-QoL improvement in the end of MDR-TB therapy, HR QoL score was considered low which indicated an impairment.Citation26,Citation33 Residual impairment of HR-QoL may have happened after prolonged therapy with high pill burden and various ADR.Citation26,Citation34 Moreover, the disease itself altered lung architecture and increased risk of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD).Citation34

Physical Well-Being

ADR generate physical distress. Major ADR can cause hospitalization, disability, or even death if not managed properly.Citation13 A meta-analysis indicates that 57.3% of MDR-TB patients experienced at least one adverse event.Citation5 A higher ADR average was found in a high-prevalence HIV setting (83%), in which 24% of the evaluated cases were considered as serious adverse events. GI disturbance such as gastritis, vomiting, and reduced appetite, was the most prevalent ADR.Citation4,Citation6 Some patients admitted that they cannot tolerate ADR. Instead of feeling better, patients felt that the outcomes following the intake of medications were as bad as the illness itself, or even worse.Citation35,Citation36

Some ADR lead to permanent disability, even when the drug has been discontinued, for example ototoxicity. A study conducted in 50 MDR-TB patients with aminoglycoside injectable agent reported that 28% of participants experienced ototoxicity and 18% of participants experienced long-term hearing loss.Citation37 Ototoxicity is one of the most common major ADR with a prevalence of 14.6%. Injectable drugs not only cause pain at the injection site but also found to be the most ADR-inducing drugs.Citation37–Citation39

Social Well-Being

Despite the social stigma of the illness itself, ADR also was a burden of social life of patients. Patient missed out a lot of social activities because they felt they are too weak to socialize. For some patients, the visible effects, such as skin discoloration, made them feel ashamed. The ADR prevented them to perform household chores. The inability to work owing to the disease and its adverse effects compelled patients to face income losses. Conversely, they also faced financial constraint to provide adequate nutritious foods and to sustain their treatment.Citation31,Citation39–Citation42 Although the treatment itself is free, patients still have to pay some indirect cost, for example transportation cost.Citation43

Mental Well-Being

ADR was also associated with psychiatric problems.Citation44 A cross-sectional study showed that 33.8% patients were depressed. Qualitative data indicated that the majority of patients feel depressed owing to side effects.Citation45 Another study revealed that the side effects were the most significant factors of depression among MDR-TB patients (aOR 20.7, 95% CI 1.2–355.7).Citation44 Patients were often depressed.Citation45 Some patients felt that their lives were only about disease and treatment.Citation40 Patients were very tortured and even some of them said that they would rather die than experience this type of terrible feeling.Citation46 The worthless feeling and disability also made them feel depressed.Citation45 Furthermore, psychiatric disorders were included in the major ADR of some drugs. A prior study reported that it occurred in 13.2% of patients.Citation5 The manifestations of these disorders can be anxiety, depression, and psychosis that may sometimes lead to suicidal attempts.Citation5,Citation6,Citation47 It could be induced by cycloserine and fluoroquinolone.Citation48 Depression and other mental problems as a consequence of DR-TB therapy may exacerbate non-adherences.Citation45

ADR and Therapeutics Adherence

ADR constitute one of the challenging aspects that may exacerbate the burden of illness. Burdened patients sometimes struggle with adhering to therapy.Citation16 Suffering with bad experiences associated with ADR may sometimes be intolerable and inflict treatment disruption.Citation39 Therefore, ADR could be considered as a barrier for DR-TB patients to achieve treatment adherence.Citation39 Some studies had demonstrated that deliberating ADR in DR-TB patients was associated with non-adherence and treatment default or loss to follow-up ().Citation46,Citation49,Citation50 Adherence itself indicates how long a patient follows the healthcare provider’s recommendation regarding the received health advice, while loss to follow-up refers to interrupted treatment for at least two consecutive months. Loss to follow-up may indicate non-adherene. Non-adherence in TB therapy may diminish effectiveness of medication and result in higher risk of treatment failure, relapse, and worse drug resistant.Citation51

Table 2 Quantitative Studies of Association Between ADR and Treatment Adherence or Outcome in MDR-TB Patients

Wang et al found that the incidence of short treatment interruption (≤14 days) among 202 MDR-TB patients was 37.6%, and serious interruption (>14 days) was 28.7%. ADR was found to be the most prominent factor of treatment interruption (ORadj: 2.82, 95% CI: 1.41–5.61) that accounted for 20.3% of serious interruption, followed by the financial related factor and comorbidity.Citation49 Another similar report by Woldeyohannes et al revealed that patients that experienced ADR were six times more likely to become loss to follow-up (AHR = 6.1; 95% CI = 2.5–14.34).Citation52

According to research conducted by Sanchez-Padilla et al (2014), the number of ADR was associated with the loss to follow-up (aRR 1.18, 95% CI 1.09–1.27). This was reinforced by their qualitative findings based on which all of the patients perceived that dealing with ADR was difficult. Poor tolerability demotivated them from continuing the treatment. The urge of discontinuing was shown to be stronger in the initial period of therapy, and caused losses to follow-up during the intensive phase (69 (71.1%) of the 97 patient). There were 11 ADR that became the main reason of loss to follow-up.Citation46

According to the study by Tupasi et al, among many ADR, high-severity vomit was the only adverse drug reaction that was independently associated with loss to follow-up in multivariate analysis (OR 1.10 (1.01–1.21), p = 0.03). Additionally, vomit was included in GI disorders, the most common ADR of DR-TB medication. Meanwhile, other side effects, such as dizziness and fatigue exhibited a significant association only in the univariate model. Patients also expressed the fact that their fears toward side effects had been the primary reason for stopping treatments.Citation50

Meanwhile, other research studies yielded slightly different results. Research conducted by Iweama et al demonstrated ADR and treatment adherence in both DS-TB and DR-TB. It showed significant bivariate correlation but insignificant multivariate correlation between side effects and treatment adherence. This may be attributed to the fact that because self-reported adherence assessment used in this study may be limited by recall and bias.Citation53 Moreover, the proportion of DS-TB patients was higher than DR-TB patients, while DS-TB did not cause severe side effects, like DR-TB did.Citation48 Similar results reported by Dela et al 2017, which found a significant association between loss to follow-up with ADR in bivariate analysis (χ2 = 20.214, degrees-of-freedom = 5, p = 0.001), as well as between adherence with no occurrence of ADR (χ2 =18.614, df = 1, p = 0.000).Citation54

Another study in Philippines demonstrated different results. This study reported that occurrence of uncontrolled adverse events during the first year of treatment was not associated with loss to follow-up (p = 0.35) in a univariate analysis.Citation55 A retrospective study conducted in Uganda also reported similar results. The study revealed that ADR was not significantly associated with non-adherence in MDR-TB patients.Citation56 In addition, a study of 788 MDR-TB patients in India suggested no significant association between ADR and unfavorable outcome (failed, died, loss to follow up, transferred out, and switched to Extensively Drug Resistant) both in univariate (p = 0.07) and multivariate (p = 0.09) analysis.Citation57 Despite patient’s decision to refuse therapy, therapy interruption could sometimes occur owing to the clinician’s recommendation regarding severe side effects or the clinical condition.Citation58

The occurrence of ADR could be either significantly or insignificantly associated with poor therapy outcomes.Citation58–Citation61 Given that non-adherence and treatment interruption was associated with poor outcomes, these states ought to be managed properly.Citation62,Citation63

Discussion

Health care is a humanistic transaction that targets the well-being of patients.Citation17 Medication, as the part of healthcare, is expected to cure and improve the QoL of patients. Otherwise, in DR-TB therapy, the existing therapeutics regimen was shown to be extremely burdensome for most patients owing to ADR.Citation36,Citation39,Citation45 Some studies reported that ADR more likely reduced HR-QoL.Citation20,Citation22 ADR is included in the burden of medicine, a term that refers to workloads that are withstood by a person who undergoes therapy and can affect their QoL, especially in a long-term therapy.Citation64–Citation66

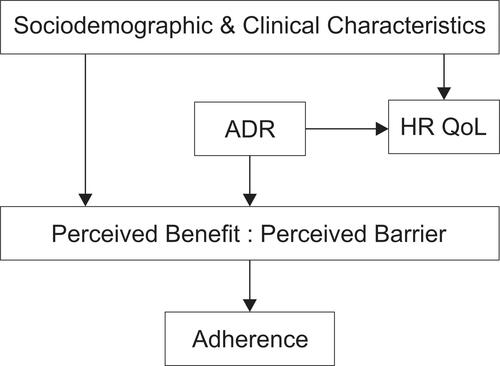

HR-QoL is more complex than just a health status, it combines some values that a patient expects.Citation17 It is about physical, mental, and social well-beings that account for the patients’ functionality.Citation27 Not only ADR, but other clinical and sociodemographic characteristics are also responsible for the patients’ HR-QoL, for example age, smoking, residence, marital status, education level, duration of current treatment, length of sickness before DR-TB, HIV comorbid, and number of drugs used.Citation25,Citation27 Low QoL predicts poor treatment outcomes owing to its impact to adherenceCitation15 ().

Figure 3 Illustration of burden of ADR and its impact to QoL and adherence.

Medication adherence is a complex phenomenon.Citation67 In addition to ADR, there were a lot of predisposing factors of DR-TB therapy non-adherence, such as being male, smoking, middle-low education level, being older than 40–45 years old, Extensively Drug Resistant (XDR), or pre-XDR-TB category, and the history of poor TB therapy outcome (loss to follow-up or failed).Citation50,Citation58,Citation68 Therefore, ADR may not always be a significant predictor of non-adherence. However, ADR is a concern that healthcare workers and care givers should pay attention to.

Based on the health belief model (HBM), perceived barriers and benefits are two direct and prominent aspects that affect adherence. Meanwhile, cues of action, perceived self-efficacy, perceived severity, perceived susceptibility, as well as sociodemographic characteristics and psychological distress were known to be the exogenous variables that indirectly affected adherence.Citation69 In this context, the example of perceived barrier is when patients believe that consuming TB drugs costs effort, time, energy, and money owing to ADR. Patients with poor physical well-being may perceive more barriers. The example of perceived benefit is when the patients believe that consuming TB drugs will improve their health states and prevent them from experiencing deteriorating conditions. Patient with good mental well-being will more easily perceive the benefit of therapy.Citation70 If perceived benefits outweigh perceived barriers, the patient may adhere to the regimen, and vice versa.

Proper strategies about ADR management have to be planned to maintain QoL and therapy adherence. Proper counseling sessions before and during therapy could build awareness and belief of necessity and convince the patients about the benefit of therapy. Knowledge or educational intervention is one of the primary efforts to strengthen the perceived benefit and reduce the perceived barrier in order to achieve adherence.Citation71,Citation72 Healthcare workers have responsibility to deliver information to patients, family, and the caregiver with comprehensive understanding about disease and treatment, including the ADR and how to handle ADR.Citation46,Citation69 Psychological and educational support could improve both HR-QoL and medication adherence.Citation63,Citation73,Citation74

Directly observed treatment (DOT) is very useful to monitor medication usage. DOT from community health workers was known to be more effective to reduce loss to follow-up rate compared with DOT from healthcare workers only from healthcare facilities like hospital. This may be attributed to the fact that healthcare workers in hospital are busy and have only limited time to talk and give support to patients.Citation75 In the implementation of DOT, adherence maintenance or improvement is a collaborative approach with a patient-centered perspective. It involves discussions and negotiations to resolve non-adherence. Instead of asking “why,” healthcare workers should view non-adherence as a chance to get more information and provide more understanding and motivational support.Citation67

Deshmukh et al explained that family, community, and healthcare workers played an important role toward QoL and adherence among DR-TB patients. Hopes and aspiration about future life, concern about their loved ones, and fear of death explained the self-motivation factors for dealing with all barriers. Family and peer attention matter a lot to provide the feeling of security and motivation for patients.Citation58,Citation72 Psychological counseling from healthcare professionals was also needed to help patients in relieving anxiety, depression, as well as motivating patients in controlling every barrier. This effort was also effective in improving adherence.Citation70

In addition to psychological and cognitive intervention, medical interventions, such as early detection, proper management, and evaluation, were also important. Regular checks and laboratory screenings according to guidelines were needed.Citation76,Citation77 Moreover, nutritional support could help patients recover more quickly.Citation78

Choi et al recommended that therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) and pharmacogenomic-based therapy could reduce the potency of ADR as well as increase therapy efficacy.Citation78 TDM could help clinicians to find optimal drug concentration which minimize ADR. Combining TDM with microbiological and clinical assessments could help optimize therapy.Citation79,Citation80 Pharmacogenomic-based individualized therapy allowed clinicians to analyze the risk of ADR that may develop in patients according to their genetic characteristics. There are some polymorphisms that are responsible for the occurrence of ADR in TB therapy.Citation81 Yet, this method is barely implemented resource in limited setting, especially in low- and middle-income countries.Citation82

However, an effective, safe, and tolerable regimen is currently required. Global need of DR-TB therapy improvement underlies several studies. Since 2016, WHO has recommended a shorter regimen for patients with certain conditions owing to the lower cost and higher adherence potential.Citation83,Citation84 Although currently there is no evidence of adherence improvement in shorter regimen, minimizing therapy period will give more confidence of patient to complete the therapy. Shorter regimen also reduces the potency of ADR and diminish therapy-related cost.Citation56 Shorter duration of treatment was also known to be associated with better QoL.Citation22 To strengthen the evidence, a multi-centered study is currently being conducted to evaluate HR QoL among patients with shorter regimen.Citation85

Several studies has proven safety and efficacy of novel and repurposed drugs for DR-TB.Citation86 A randomized control trial showed that Delamanid and Bedaquiline both drugs showed good conversion rate.Citation87 The occurrence of QT prolongation has been a concern of using both drugs.Citation88,Citation89 Bedaquiline, also showed good clinical outcome in combination with moxifloxacin, pretomanid, and pyrazinamide with shorter regimen. Liver enzyme abnormality was found.Citation90 While study in China showed favorable clinical outcome from regimen containing linezolid, fluoroquinolone, clofazimine/bedaquiline, cycloserine, and pyrazinamide. Peripheral neuropathy and arthralgia/myalgia were the most frequent ADR in this regiment. Pyrazinamide and linezolid were two-most ADR inducing drugs.Citation91 Based on the existing studies, it can be concluded that delamanid, bedaquiline, clofazimine, pretomanid, fluoroquinolone, and linezolid are novel and repurposed drugs that effective and well tolerated. These agents are promising and may improve QoL and adherence of DR TB patients.

Conclusion and Prospects

Burden of ADR makes DR-TB therapy to be a miserable period for patients. ADR generally tend to degrade quality of life of patients and potentially influence the adherence. A comprehensive support from family, community, and healthcare provider is required to help patients in coping with the burden of ADR. Nevertheless, the regimen improvement is highly needed. There is still lack of research that conducts analysis of the burden of medicine either in general or specifically regarding to ADR. Therefore, this topic ought to be investigated further.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis. Module 4: Treatment - Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Treatment. Online Annexes. World Health Organization; 2020.

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

- World Health Organization. Safety of Medicines. Vol. 2. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

- Schnippel K, Berhanu RH, Black A, et al. Severe adverse events during second-line tuberculosis treatment in the context of high HIV Co-infection in South Africa: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1933-0

- Wu S, Zhang Y, Sun F, et al. Adverse events associated with the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ther. 2016;23(2):e521–e530. doi:10.1097/01.mjt.0000433951.09030.5a

- Schnippel K, Firnhaber C, Berhanu R, Page-Shipp L, Sinanovic E. Adverse drug reactions during drug-resistant TB treatment in high HIV prevalence settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(7):1871–1879. doi:10.1093/jac/dkx107

- Xu HB, Jiang RH, Xiao HP. Clofazimine in the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(11):1104–1110. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03716.x

- Yang TW, Park HO, Jang HN, et al. Side effects associated with the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis at a tuberculosis referral hospital in South Korea. Medicine. 2017;96(28). doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000007482

- Zhang Y, Wu S, Xia Y, et al. Adverse events associated with treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in China: an ambispective cohort study. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:2348–2356. doi:10.12659/MSM.904682

- Isaakidis P, Varghese B, Mansoor H, et al. Adverse events among HIV/MDR-TB co-infected patients receiving antiretroviral and second line anti-TB treatment in Mumbai, India. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40781. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040781

- Mehta S, Das M, Laxmeshwar C, Jonckheere S, Thi SS, Isaakidis P. Linezolid-associated optic neuropathy in drug-resistant tuberculosis patients in Mumbai, India. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):1–12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0162138

- Michalak K, Sobolewska-Włodarczyk A, Włodarczyk M, Sobolewska J, Woźniak P, Sobolewski B. Treatment of the Fluoroquinolone-Associated Disability: the Pathobiochemical Implications. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:1–15. doi:10.1155/2017/8023935

- Borisov S, Danila E, Maryandyshev A, et al. Surveillance of adverse events in the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis: first global report. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(6):1901522. doi:10.1183/13993003.01522-2019

- Thomas BE, Shanmugam P, Malaisamy M, et al. Psycho-socio-economic issues challenging multidrug resistant tuberculosis patients: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):1–15. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147397

- Mohammed MA, Moles RJ, Chen TF. Medication-related burden and patients’ lived experience with medicine: a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e010035. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010035

- Eton D, Ramalho de Oliveira D, Egginton J, et al. Building a measurement framework of burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditions: a qualitative study. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2012:39. doi:10.2147/prom.s34681

- World Health Organization. WHOQOL User Manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998. doi:10.4091/iken1991.9.1_123

- Ebrahim S. Clinical and public health perspectives and applications of health-related quality of life measurement. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(10):1383–1394. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(95)00116-O

- Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Quality of Life: what is the Difference? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(7):645–649. doi:10.1007/s40273-016-0389-9

- Valadares RMC, Carvalho W, de Miranda SS. Association of adverse drug reaction to anti-tuberculosis medication with quality of life in patients in a tertiary referral hospital. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;53(August):1. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0207-2019

- Masumoto S, Yamamoto T, Ohkado A, Yoshimatsu S, Querri AG, Kamiya Y. Factors associated with health-related quality of life among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Manila, the Philippines. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(5):1523–1533. doi:10.1007/s11136-013-0571-x

- Sineke T, Evans D, Schnippel K, et al. The impact of adverse events on health-related quality of life among patients receiving treatment for drug-resistant tuberculosis in Johannesburg, South Africa. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1). doi:10.1186/s12955-019-1155-4

- Lange C, Abubakar I, Alffenaar JWC, et al. Management of patients with multidrug-resistant/ extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in Europe: a TBNET consensus statement. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(1):23–63. doi:10.1183/09031936.00188313

- Alene KA, Clements ACA, McBryde ES, et al. Mental health disorders, social stressors, and health-related quality of life in patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2018;77(5):357–367. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2018.07.007

- Datta S, Gilman RH, Montoya R, et al. Quality of life, tuberculosis and treatment outcome; a case-control and nested cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(2):1900495. doi:10.1183/13993003.00495-2019

- Ahmad N, Javaid A, Sulaiman SAS, et al. Effects of multidrug resistant tuberculosis treatment on patients’ health related quality of life: results from a follow up study. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):1–16. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159560

- Jaber AAS, Ibrahim B. Health-related quality of life of patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Yemen: prospective study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):1–14. doi:10.1186/s12955-019-1211-0

- Kuchukhidze G, Kumar AMV, Colombani P, et al. Risk factors associated with loss to follow-up among multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients in Georgia. Public Heal Action. 2017;7(1).

- Kassa GM, Teferra AS, Wolde HF, Muluneh AG, Merid MW. Incidence and predictors of lost to follow-up among drug-resistant tuberculosis patients at University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: a retrospective follow-up study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4447-8

- Sagwa EL, Ruswa N, Mavhunga F, Rennie T, Leufkens HG, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK. Adverse events and patients’ perceived health-related quality of life at the end of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment in Namibia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:2369–2377. doi:10.2147/PPA.S116860

- Ting NCH, El-Turk N, Chou MSH, Dobler CC. Patient-perceived treatment burden of tuberculosis treatment. PLoS One. 2020;15(10 October):1–13. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0241124

- Sagwa E, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Ruswa N, et al. The burden of adverse events during treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis in Namibia. South Med Rev. 2012;5(1):6–13.

- Kastien-Hilka T, Rosenkranz B, Sinanovic E, Bennett B, Schwenkglenks M. Health-related quality of life in South African patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):1–20. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0174605

- Nuwagira E, Stadelman A, Baluku JB, et al. Obstructive lung disease and quality of life after cure of multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis in Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Trop Med Health. 2020;48(1). doi:10.1186/s41182-020-00221-y

- Isaakidis P, Paryani R, Khan S, Mansoor H, Manglani M. Poor Outcomes in a Cohort of HIV-Infected Adolescents Undergoing Treatment for Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Mumbai, India. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68869. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068869

- Gebreweld FH, Kifle MM, Gebremicheal FE, et al. Factors influencing adherence to tuberculosis treatment in Asmara, Eritrea: a qualitative study. J Heal Popul Nutr. 2018;37(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s41043-017-0132-y

- Sturdy A, Goodman A, Joś RJ, et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) treatment in the UK: a study of injectable use and toxicity in practice. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(8):1815–1820. doi:10.1093/jac/dkr221

- Reuter A, Tisile P, Von Delft D, et al. The devil we know: is the use of injectable agents for the treatment of MDR-TB justified? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21(11):1114–1126. doi:10.5588/ijtld.17.0468

- Shringarpure KS, Isaakidis P, Sagili KD, Baxi RK, Das M, Daftary A. “When treatment is more challenging than the disease”: a qualitative study of MDR-TB patient retention. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):1–12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150849

- Horter S, Stringer B, Greig J, et al. Where there is hope: a qualitative study examining patients’ adherence to multi-drug resistant tuberculosis treatment in Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):1–15. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1723-8

- Laxmeshwar C, Stewart AG, Dalal A, et al. Beyond ‘cure’ and ‘treatment success’: quality of life of patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2019;23(1):73–81. doi:10.5588/ijtld.18.0149

- Deshmukh RD, Dhande DJ, Sachdeva KS, et al. Patient and provider reported reasons for lost to follow up in MDRTB treatment: a qualitative study from a drug resistant TB Centre in India. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):1–11. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135802

- Dos Santos FL, Souza LLL, Bruce ATI, et al. Patients’ perceptions regarding multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and barriers to seeking care in a priority city in Brazil during COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2021;16(4 April):1–19. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0249822

- Walker IF, Khan AM, Khan AM, et al. Depression among multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients in Punjab, Pakistan: a large cross-sectional study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018;22(7):773–778. doi:10.5588/ijtld.17.0788

- Huque R, Elsey H, Fieroze F, et al. “death is a better option than being treated like this”: a prevalence survey and qualitative study of depression among multi-drug resistant tuberculosis in-patients. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–13. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-08986-x

- Sanchez-Padilla E, Marquer C, Kalon S, et al. Reasons for defaulting from drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment in Armenia: a quantitative and qualitative study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(2):160–167. doi:10.5588/ijtld.13.0369

- Brust JCM, Shah NS, Van Der Merwe TL, et al. Adverse events in an integrated home-based treatment program for MDR-TB and HIV in kwazulu-natal, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(4):436–440. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828175ed

- Carroll MW, Lee M, Cai Y, et al. Frequency of adverse reactions to first-and second line antituberculosis chemotherapy in a Korean cohort. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2019;16(7):961–966. doi:10.5588/ijtld.11.0574.Frequency

- Wang Y, Chen H, Mcneil EB, Lu X. Drug Non-Adherence And Reasons Among Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis Patients In Guizhou, China: a Cross-Sectional Study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;1641–1653.

- Tupasi TE, Marie A, Garfin CG, et al. Factors Associated with Loss to Follow-up during Treatment for. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(3):2012–2014. doi:10.3201/eid2211.160728

- World Health Organization. Adherence to Long-Term Therapy: Evidence for Action. Geneva; 2003.

- Woldeyohannes D, Tekalegn Y, Sahiledengle B. Predictors of mortality and loss to follow-up among drug resistant tuberculosis patients in Oromia Hospitals, Ethiopia: a retrospective follow-up study. PLoS One. 2021;71:1–15. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0250804

- Iweama CN, Agbaje OS, Christian P, et al. Nonadherence to tuberculosis treatment and associated factors among patients using directly observed treatment short-course in north-west Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:205031212198949. doi:10.1177/2050312121989497

- Dela AI, Tank NKD, Singh AP, Piparva KG. Adverse drug reactions and treatment outcome analysis of DOTS-plus therapy of MDR-TB patients at district tuberculosis centre: a four year retrospective study. Lung India. 2017;34(6):522–526. doi:10.4103/0970-2113.217569

- Gler MT, Podewils LJ, Munez N, Galipot M, Quelapio MID. Tupasi and TE. Impact of patient and program factors on default during treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;16(7):955–960. doi:10.5588/ijtld.11.0502.Impact

- Batte C, Namusobya MS, Kirabo R, Mukisa J, Batte C. Prevalence and factors associated with non-adherence to multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) treatment at Mulago National Referral Hospital. Kampala Uganda. 2021;21(1):238–247.

- Nair D, Velayutham B, Kannan T, et al. Predictors of unfavourable treatment outcome in patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in India. Public Heal Action. 2017;7(1):254.

- Bastard M, Sanchez-padilla E, Hewison C, et al. Effects of Treatment Interruption Patterns on Treatment Success Among Patients With Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Armenia and Abkhazia. J Infect Dis. 2015;211(10):1607–1615. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiu551

- Rupani MP, Dave JD, Parmar VB, Singh MP, Parikh KD. Adverse drug reactions and risk factors for discontinuation of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis regimens in Gujarat, western India. Natl Med J India. 2020;33(1):10–14. doi:10.4103/0970-258X.308234

- Patel SV, Nimavat KB, Alpesh PB, et al. Treatment outcome among cases of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR TB) in Western India: a prospective study. J Infect Public Health. 2016;9(4):478–484. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2015.11.011

- Zhang L, Meng Q, Chen S, et al. Treatment outcomes of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients in Zhejiang, China, 2009–2013. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(4):381–388. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.07.008

- Gelmanova IY, Keshavjee S, Golubchikova VT, et al. Barriers to successful tuberculosis treatment in Tomsk, Russian Federation: non-adherence, default and the acquisition of multidrug resistance. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;85(9):703–711. doi:10.2471/BLT

- Tola HH, Holakouie-na K, Mansournia MA. Intermittent treatment interruption and its effect on multidrug resistant tuberculosis treatment outcome in. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–10. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-56553-1

- Tran VT, Barnes C, Montori VM, Falissard B, Ravaud P. Taxonomy of the burden of treatment: a multi-country web-based qualitative study of patients with chronic conditions. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):1–15. doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0356-x

- Sav A, King MA, Whitty JA, et al. Burden of treatment for chronic illness: a concept analysis and review of the literature. Heal Expect. 2015;18(3):312–324. doi:10.1111/hex.12046

- Krska J, Katusiime B, Corlett SA. Patient experiences of the burden of using medicines for long-term conditions and factors affecting burden: a cross-sectional survey. Heal Soc Care Commun. 2018;26(6):946–959. doi:10.1111/hsc.12624

- Gould E, Mitty E. Medication Adherence is a Partnership, Medication Compliance is Not. Geriatr Nurs (Minneap). 2010;31(4):290–298. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.05.004

- Lalor MK, Greig J, Allamuratova S, et al. Risk Factors Associated with Default from Multi- and Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Treatment, Uzbekistan: a Retrospective Cohort Analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e78364. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078364

- Tola HH, Karimi M, Yekaninejad MS. Effects of sociodemographic characteristics and patients’ health beliefs on tuberculosis treatment adherence in Ethiopia: a structural equation modelling approach. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s40249-017-0380-5

- Tola HH, Shojaeizadeh D, Tol A, et al. Psychological and educational intervention to improve tuberculosis treatment adherence in Ethiopia based on health belief model: a cluster randomized control trial. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):1–15. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155147

- Abiz M, Robabi H, Salar A, Saeedinezhad F. The Effect of Self-Care Education on the Quality of Life in Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Med Surg Nurs J. 2020;9(2). doi:10.5812/msnj.108877

- Deshmukh RD, Dhande DJ, Sachdeva KS, Sreenivas AN, Kumar AMV, Parmar M. Social support a key factor for adherence to multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment. Indian J Tuberc. 2018;65(1):41–47. doi:10.1016/j.ijtb.2017.05.003

- Horne R, Chapman SCE, Parham R, Freemantle N, Forbes A, Cooper V. Understanding patients’ adherence-related Beliefs about Medicines prescribed for long-term conditions: a meta-analytic review of the Necessity-Concerns Framework. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e80633. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080633

- Zhang Y, Zhao X. Effects of the Health Belief Model-Based Intervention on Anxiety, Depression, and Quality of Life in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2021;28(3):129–136. doi:10.1159/000512993

- Toczek A, Cox H, Du Cros P, Cooke G, Ford N. Strategies for reducing treatment default in drug-resistant tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(3):299–307. doi:10.5588/ijtld.12.0537

- Lange C, Aarnoutse RE, Alffenaar JWC, et al. Management of patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2019;23(6):645–662. doi:10.5588/ijtld.18.0622

- Curry International Tuberculosis Centre & California Departement of Public Health. Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis: A Survival Guide for Clinicians. Third ed. USA: CITC & the State of California Department of Public Health, Tuberculosis Control Branch (CDPH); 2016.

- Choi R, Jeong BH, Koh WJ, Lee SY. Recommendations for optimizing tuberculosis treatment: therapeutic drug monitoring, pharmacogenetics, and nutritional status considerations. Ann Lab Med. 2017;37(2):97–107. doi:10.3343/alm.2017.37.2.97

- Wilby KJ, Ensom MHH, Marra F. Review of Evidence for Measuring Drug Concentrations of First-Line Antitubercular Agents in Adults. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2014;53(10):873–890. doi:10.1007/s40262-014-0170-1

- Alsultan A, Peloquin CA. Therapeutic drug monitoring in the treatment of tuberculosis: an update. Drugs. 2014;74(8):839–854. doi:10.1007/s40265-014-0222-8

- Matsumoto T, Ohno M, Azuma J. Future of pharmacogenetics-based therapy for tuberculosis. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15(5):601–607. doi:10.2217/pgs.14.38

- Olsson S. Overview of pharmacovigilance in resource limited settings: challenges and opportunities. Clin Ther. 2013;35(8):e122–e123. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.07.379

- Silva DR, Mello FC, Migliori GB. Shortened tuberculosis treatment regimens: what is new? J Bras Pneumol. 2020;46(2):1–8. doi:10.36416/1806-3756/e20200009

- World Health Organization. What is New in the WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Treatment? Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. doi:10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_579_19

- Stringer B, Lowton K, James N, Nyang’wa BT. Capturing patient-reported and quality of life outcomes with use of shorter regimens for drug-resistant tuberculosis: mixed-methods substudy protocol, TB PRACTECAL-PRO. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):1–6. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043954

- Grace A, Mittal A, Jain S, et al. Shortened treatment regimens versus the standard regimen for drug-sensitive pulmonary tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;12.

- Dooley KE, Rosenkranz SL, Conradie F, et al. QT effects of bedaquiline, delamanid, or both in patients with rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis: a Phase 2, open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(7):975–983. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30770-2

- Pym AS, Diacon AH, Tang SJ, et al. Bedaquiline in the treatment of multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(2):564–574. doi:10.1183/13993003.00724-2015

- Diacon AH, Pym A, Grobusch MP, et al. Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis and Culture Conversion with Bedaquiline. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(8):723–732. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1313865

- Tweed CD, Dawson R, Burger DA, et al. Bedaquiline, moxifloxacin, pretomanid, and pyrazinamide during the first 8 weeks of treatment of patients with drug-susceptible or drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis: a multicentre, open-label, partially randomised, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(12):1048–1058. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30366-2

- Fu L, Weng T, Sun F, et al. Insignificant difference in culture conversion between bedaquiline-containing and bedaquiline-free all-oral short regimens for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;111:138–147. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.08.055