Abstract

Background:

The aim of this pilot study was to evaluate patients’ self-reported attitudes towards medication-related factors known to impair adherence and to assess their prevalence in ambulatory care as an essential prerequisite to improve patient adherence.

Methods:

We conducted a face-to-face interview with 110 primary care patients maintained on at least one drug. For each drug, the patient was asked to specify medication-related factors of interest, ie, dosage form, dosage interval, required relationship with food intake, and the planned time of day for intake, and to rate the individual relevance of each prevalent parameter on a three-point Likert scale (discriminating between prefer, neutral, and dislike).

Results:

Tablets with a once-daily dosage frequency were the most preferred dosage form, with a high prevalence in the ambulatory setting. Drug intake in the morning and evening were most preferred, and drug intake at noon was least preferred, but also had a low prevalence in contrast with drug intake independent of meals that was most preferred. Interestingly, only one quarter (26.4%) of all the patients were able to indicate clear preferences or dislikes.

Conclusion:

When patients are asked to specify their preferences for relevant medication regimen characteristics, they clearly indicated regimens that have been associated with better adherence in earlier studies. Therefore, our results suggest that adaptation of drug regimens to individual preferences might be a promising strategy to improve adherence. Because the German health care system may differ from other systems in relevant aspects, our findings should be confirmed by evaluation of patient preferences in other health care systems. Once generalizability of the study results is shown, these findings could be a promising basis upon which to promote patient adherence right from the beginning of drug therapy.

Introduction

Patient adherence with drug treatment is an important predictor of the success of drug therapy.Citation1–Citation3 However, a multitude of factors related to the patient, medication, disease (eg, symptomatology), provider (eg, patient–provider relationship), and health care system (eg, copayment) may impair adherence and consequently impact successful drug treatment.Citation4,Citation5 Patient-related factors reducing adherence with drug therapy include a decline in cognitive function, skepticism about the benefit of long-term treatment and its consequences on health, and low health literacy.Citation6–Citation9 Medication-related factors with a negative impact on patient adherence involve multiple dosages per day,Citation10–Citation21 certain dosage forms,Citation22,Citation23 additional handling directions like tablet splitting,Citation22,Citation24 and dependency on food intake.Citation11,Citation12,Citation14 Hence, medication-related factors might be particularly promising targets for strategies that aim at improving patient adherence because many of them can be rather easily modified and corrected.Citation25 However, not all of these characteristics are barriers to treatment success in all patients and, interestingly, pill burden per se is not a relevant barrier in all patients, so smooth integration of the regimen into the daily activities of the individual may be more important.Citation26 Therefore, when eliminating problematic medication-related characteristics, patient preferences should also be considered. Indeed, patient preferences are particularly important during shared decision-making, a technique that successfully increases patient adherence and improves the clinical outcome.Citation27,Citation28 Most studies assessing patient preferences have focused on the decision to start or not to start a drug therapy due to potential harm (eg, medication side effects) or benefit (eg, effectiveness for specific symptoms).Citation27–Citation29 Hence, the aim of this study was to evaluate how patients perceive different medication-related factors and to assess the prevalence of these factors in ambulatory care as an essential prerequisite for a successful intervention.

Materials and methods

The study was performed between January 28, 2011 and February 4, 2011 in ambulatory patients who were predominantly accessed via one large private practice in Germany. After approval by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg, we conducted a face-to-face interview with 110 ambulatory care patients taking at least one long-term medication (ie, prescription of at least one drug for the treatment of a chronic disorder). During the interview, we noted for each patient on an anonymized documentation sheet the number of prescription and nonprescription drugs and the total duration for which the patient had taken at least one drug. For each drug, the patient was asked to specify the medication-related factors of interest, ie, dosage form, dosage interval, required relationship with food intake, and the time of day the drug was supposed to be taken. Thereby, we evaluated the prevalence of each factor. We excluded all details with a prevalence < 10% from the interpretation; however, we kept them for illustration purposes in the respective figures. In addition to collection of objective medication-related information, we also surveyed the individual appraisal of each prevalent parameter on a three-point Likert scale (discriminating between prefer, neutral, and dislike). In addition to analysis of the whole data set, patients were allocated into two groups, ie, those who either did or did not express clear preferences in the majority of responses. For this purpose, we arbitrarily defined patients with clear preferences as those who gave <20% neutral responses and all others as patients without clear preferences. Because of the anonymous nature of the interview, we did not capture demographic characteristics, such as patient age and gender, and did not record individual drugs.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed descriptively and reported as proportions and means, including standard deviations. Prevalence was calculated as the proportion of patients with a distinct medication-related characteristic, with medication-related characteristics having low prevalence (ie, <10%) being excluded. Preference was calculated as the proportion of patients who preferred the respective characteristic of all patients with the respective medication-related characteristic. Preferences of different medication-related characteristics were compared by Chi-square test. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 19 (IBM® SPSS® Statistics, Armonk, NY).

Results

We interviewed 110 primary care patients with at least one long-term treatment about their drug use. Most of the patients (n = 82, 74.5%) had taken their medication for at least 6 years, with 58 patients (52.7%) having taken their medication for more than 10 years. The mean number of drugs was 4.0 ± 1.9 and comprised 3.2 ± 1.7 prescription and 0.9 ± 0.9 nonprescription drugs, with 58.2% of patients taking at least one nonprescription drug. Five patients did not specify their drug count, except for indicating that it comprised >10 drugs. These patients were excluded from the analyses assessing drug numbers.

To estimate the validity of the statements made by the patients, we conducted a separate analysis to evaluate whether the views of patients with clear preferences differed from those in the overall population. Of all 110 patients, 29 (26.4%) were able to indicate clear preferences or dislikes relating to dosage frequencies, dosage forms, times of day, and drug–food relationships in 80% of their responses. Most patients (n = 69, 62.7%) indicated clear preferences only for some of the medication-related characteristics, and in some patients (n = 12, 10.9%), the neutral ranking was most prevalent.

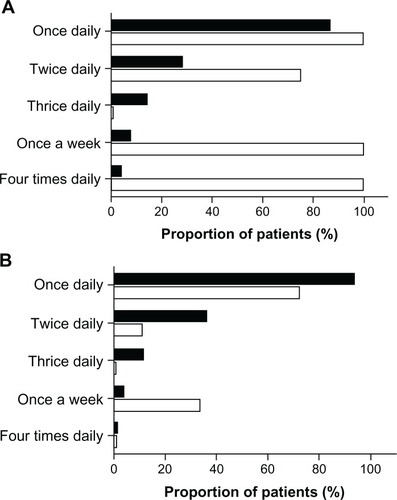

Frequency and preference of different dosage frequencies

Once-daily drug intake was the most common dosage frequency (91.8%), and preferred by the majority (79.2%) of the overall study population. Preferences decreased with increasing number of daily applications, with no preference for three times daily drug applications. Nine times more patients preferred once-daily application compared with more frequent applications (P < 0.001). Dosage frequencies like “every three days” or “once a week” were also highly valued by the patients (100% and 60%, respectively); however, their prevalence was very low (0.9% and 4.5%). A separate analysis of results for patients who were able to indicate clear preferences () revealed higher proportions of patients who preferred a once-daily or twice-daily dosage frequency than patients who did not indicate clear preferences (P < 0.001, ).

Figure 1 (A) Frequency (▪) and preference (□) of different dosage frequencies as expressed by 29 general practice patients expressing clear views and preferences for most characteristics assessed. (B) Frequency (▪) and preference (□) of different dosage frequencies as expressed by 81 general practice patients without an ability to express clear views and preferences for most characteristics assessed.

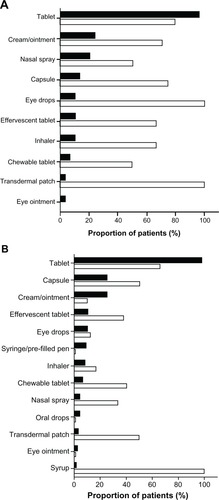

Frequency and preference of different dosage forms

Tablets were the most prevalent (97.3%) and also the preferred dosage form (68.2%) in the overall study population. Creams/ointments and capsules were also applied by more than 20% of the patients (24.5% and 21.8%, respectively). However, there was a significantly higher preference for capsules than for creams or ointments (54.2% versus 25.9%, P < 0.001). Also, there was a high preference for syrup and patches (100% and 66.7%), but these were prescribed only rarely (for 0.9% and 2.7% of patients, respectively). The dosage forms with the lowest preference were eye ointments, drops for oral use, and prefilled pens for injection (not preferred by any patient) but their prevalence was very low (<10%). In contrast, patients with clear preferences also rated eye drops as a preferred dosage form (). Differences in ratings of dosage forms between patients with or without clear preferences are shown in .

Figure 2 (A) Frequency (▪) and preference (□) of different dosage forms as expressed by 29 general practice patients expressing clear views and preferences for most characteristics assessed. (B) Frequency (▪) and preference (□) of different dosage forms as expressed by 81 general practice patients without an ability to express clear views and preferences for most characteristics assessed.

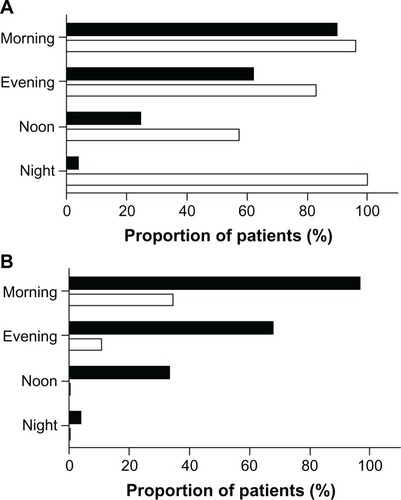

Frequency and preference of different times of day for drug application

Most of the patients in this study population had to take their drugs in the morning (94.5%), and half of them preferred to take their drugs at that time of day. Drug intake in the evening was also common (66.4%) and was the time of the day preferred by one quarter of the patients, but drug intake in the morning had higher patient acceptance (P < 0.001). Within our study population, drug intake at night showed the highest preference (62.5%) but with low prevalence (7.3%). The time of day with the lowest patient preference was noon (11.8%, prevalence 30.9%; P = 0.001) compared with all other time points. The ratings were similar in the subgroups of patients with or without clear preferences ().

Figure 3 (A) Frequency (▪) and preference (□) of different times of the day for drug application as expressed by 29 general practice patients expressing clear views and preferences for most characteristics assessed. (B) Frequency (▪) and preference (□) of different times of the day for drug application as expressed by 81 general practice patients without an ability to express clear views and preferences for most characteristics assessed.

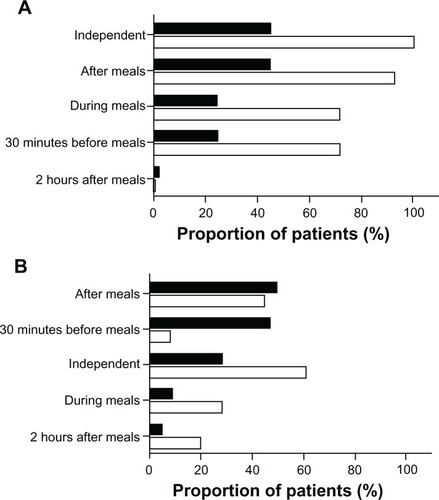

Prevalence and preference of different drug–food relationships

Most patients in the overall study population preferred to take drugs independently of meals (75.0%, prevalence 32.7%) or after meals (56.6%, prevalence 48.2%). The lowest preference was given to medication taken 30 minutes before meals (17.8%, prevalence 40.9%). However, patients with clear preferences rated drug intake 30 minutes before meals and during meals with the same preference and showed some differences compared with the subgroup of patients without clear preferences ().

Figure 4 (A) Frequency (▪) and preference (□) of different drug–food relationships expressed by 29 general practice patients expressing clear views and preferences for most characteristics assessed. (B) Frequency (▪) and preference (□) of different drug–food relationships expressed by 81 general practice patients without an ability to express clear views and preferences for most characteristics assessed.

Discussion

Active patient involvement into the treatment process (shared decision-making) is critical to the success of treatment,Citation30 and consideration of patient preferences is an essential element to foster feasibility of a treatment, its acceptance, and ultimately adherence with drug therapy.Citation31,Citation32 Therefore, we evaluated patient attitudes towards different medication-related factors and assessed their prevalence in ambulatory care. Tablets with a once-daily administration scheme were most frequently prescribed and also the patients’ preferred dosage form and frequency. The clear preference for once-daily administration confirmed the results of earlier studies showing that adherence decreases with increasing number of daily drug administrations,Citation10,Citation15,Citation16,Citation21,Citation33 and thus emphasizes the impact of dosage frequency on adherence. Importantly, simplification of multidose prescriptions to a once-daily dosing regimen is possible in 18% of all cases, and is thus a promising strategy for optimizing patient preference.Citation25 In addition, drug intake at noon was least accepted, confirming earlier findings of lower adherence with drug intake at this time of day.Citation15 Also, rigid schedules of drug intake and meals (such as application 30 minutes before meals or 2 hours after meals) expectedly had only low acceptance rates.

From a theoretical point of view, patient preferences may have many different causes. First, patients might prefer specific medication-related characteristics because they seem associated with a drug effect. For instance, asthma patients like inhalers to the same extent as oral dosage forms (tablets or capsules)Citation34 and because medication-related characteristics and perceived effect are closely and likely positively related, this is likely not an unbiased assessment. Second, patient preference might also result from better tolerability of drugs.Citation35 For instance, many patients preferred drug administration after meals. This might result from perceived and often documented better tolerability of drugs if taken after meals. On the other hand, drug administration independent of meals was clearly preferred. For many patients, the preferred method of drug intake is linked to characteristics that best fit into their daily life and do not inflict any constraints on them,Citation35–Citation37 and developing routines for self-management of medication is very challenging for patients.Citation38 If drugs can be taken independent of meals, no special considerations are required.

In our patient population, only 26.4% indicated clear preferences for most medication-related characteristics. The results for this subgroup mostly reflect the results of the overall study population, but in a more distinct way. Divergent rankings occasionally occurred, eg, regarding preferences for drug intake, in that while the study population overall preferred drug intake during meals, patients with preferences ranked drug intake half an hour before meals equally high. Because patient preferences may modulate adherence to drug treatment,Citation33,Citation39 patients should be encouraged to express their preferences based on different factors concerning lifestyle and physical skills. For example, it may be critical to adapt drug intake as much as possible to their daily habits and to select the most convenient medication regimen, application technique, or dosage forms, but must also consider relevant limitations, such as dysphagia.Citation40

Furthermore, in addition to modification by patient preferences, patient adherence is determined by a multiplicity of factors alone or in combination, including the patient-provider relationship, patient characteristics, the clinical setting, or the disease itself.Citation41 Therefore, assessment of patient preferences and incorporation of drug therapy in the daily routine is only one method of optimizing patient adherence and should be repeatedly evaluated to detect and consider changes in daily routine or behavior.

This study has several limitations. Because of our anonymized study design, we did not document patient characteristics, including age, gender, or comorbidities. Therefore, we could not evaluate the impact of patient-related characteristics on preferences for different medication-related issues. Furthermore, we interviewed only a small albeit unselected population of primary care patients. Therefore, some medication-related characteristics applied only to a small group of patients and, consequently, preferences and prevalence could have been overestimated or underestimated. Further, we only included patients with at least one long-term treatment. Therefore, patients who stopped medication therapy due to dislike of certain medication regimen characteristics would not have been captured by this approach. Finally, in our survey, we combined creams and ointments because patients are often not familiar with the difference. Obviously, the properties of these dosage forms differ, so patient preferences may also differ. For these reasons, our study provides only preliminary evidence on these dosage forms.

Conclusion

Only a small proportion of ambulatory patients are able to indicate clear preferences with regard to medication-related characteristics. Therefore, patients should be encouraged and empowered to express their preferences as a prerequisite for shared decision-making and active participation in the treatment process. In this study, patients who were able to indicate their preferences clearly opted for regimens that had been associated with better adherence in earlier studies. Therefore, these results suggest that adaptation of drug regimens to individual preferences might be a promising strategy to improve adherence. Because the German health care system may differ from other systems in relevant aspects, our findings should be confirmed by evaluation of patient preferences in other health care systems. Once generalizability of the study results is shown, these findings could be a promising basis to promote patient adherence right from the beginning of drug therapy.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported in part by a grant from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research of Germany (BMBF 01GK0801).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- Al-QazazHSulaimanSAHassaliMADiabetes knowledge, medication adherence and glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetesInt J Clin Pharm20113361028103522083724

- DragomirACoteRRoyLImpact of adherence to antihypertensive agents on clinical outcomes and hospitalization costsMed Care201048541842520393367

- KaiserRMSchmaderKEPieperCFLindbladCIRubyCMHanlonJTTherapeutic failure-related hospitalisations in the frail elderlyDrugs Aging200623757958616930086

- OsterbergLBlaschkeTAdherence to medicationN Engl J Med2005353548749716079372

- IckovicsJRMeadeCSAdherence to HAART among patients with HIV: breakthroughs and barriersAIDS Care200214330931812042076

- GelladWFGrenardJLMarcumZAA systematic review of barriers to medication adherence in the elderly: looking beyond cost and regimen complexityAm J Geriatr Pharmacother201191112321459305

- HuasDDebiaisFBlotmanFCompliance and treatment satisfaction of post menopausal women treated for osteoporosis. Compliance with osteoporosis treatmentBMC Womens Health2010102620727140

- InselKMorrowDBrewerBFigueredoAExecutive function, working memory, and medication adherence among older adultsJ Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci2006612P102P10716497953

- KripalaniSGattiMEJacobsonTAAssociation of age, health literacy, and medication management strategies with cardiovascular medication adherencePatient Educ Couns201081217718120684870

- PaesAHBakkerASoe-AgnieCJImpact of dosage frequency on patient complianceDiabetes Care19972010151215179314626

- ChesneyMAFactors affecting adherence to antiretroviral therapyClin Infect Dis200030Suppl 2S171S17610860902

- StoneVEHoganJWSchumanPAntiretroviral regimen complexity, self-reported adherence, and HIV patients’ understanding of their regimens: survey of women in the her studyJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200128212413111588505

- CorsonelloAPedoneCLattanzioFRegimen complexity and medication nonadherence in elderly patientsTher Clin Risk Manag20095120921619436625

- AmmassariATrottaMPMurriRCorrelates and predictors of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: overview of published literatureJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200231Suppl 3S123S12712562034

- EisenSAMillerDKWoodwardRSSpitznagelEPrzybeckTRThe effect of prescribed daily dose frequency on patient medication complianceArch Intern Med19901509188118842102668

- ClaxtonAJCramerJPierceCA systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication complianceClin Ther20012381296131011558866

- MaitlandDJacksonAOsorioJMandaliaSGazzardBGMoyleGJSwitching from twice-daily abacavir and lamivudine to the once-daily fixed-dose combination tablet of abacavir and lamivudine improves patient adherence and satisfaction with therapyHIV Med20089866767218631255

- CramerJAMattsonRHPreveyMLScheyerRDOuelletteVLHow often is medication taken as prescribed? A novel assessment techniqueJAMA198926122327332772716163

- McDonaldHPGargAXHaynesRBInterventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: scientific reviewJAMA2002288222868287912472329

- KardasPCompliance, clinical outcome, and quality of life of patients with stable angina pectoris receiving once-daily betaxolol versus twice daily metoprolol: a randomized controlled trialVasc Health Risk Manag20073223524217580734

- SainiSDSchoenfeldPKaulbackKDubinskyMCEffect of medication dosing frequency on adherence in chronic diseasesAm J Manag Care2009156e22e3319514806

- LamPWLumCMLeungMFDrug non-adherence and associated risk factors among Chinese geriatric patients in Hong KongHong Kong Med J200713428429217664533

- BuysmanEConnerCAagrenMBouchardJLiuFAdherence and persistence to a regimen of basal insulin in a pre-filled pen compared to vial/syringe in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetesCurr Med Res Opin20112791709171721740289

- Hixson-WallaceJADotsonJBBlakeySAEffect of regimen complexity on patient satisfaction and compliance with warfarin therapyClin Appl Thromb Hemost200171333711190902

- WittickeDSeidlingHMLohmannKSendAFJHaefeliWEOpportunities to reduce medication regimen complexity: a retrospective analysis of 500 patients at discharge from internal medicine of a university hospitalDrug Saf2012In press.

- GiffordALBormannJEShivelyMJWrightBCRichmanDDBozzetteSAPredictors of self-reported adherence and plasma HIV concentrations in patients on multidrug antiretroviral regimensJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200023538639510866231

- FriedTRBradleyEHTowleVRAssessment of patient preferences: integrating treatments and outcomesJ Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci2002576S348S35412426443

- HauberABMohamedAFJohnsonFRFalveyHTreatment preferences and medication adherence of people with Type 2 diabetes using oral glucose-lowering agentsDiabet Med200926441642419388973

- Van BruntKMatzaLSClassiPMJohnstonJAPreferences related to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and its treatmentPatient Prefer Adherence20115334321311700

- SayREThomsonRThe importance of patient preferences in treatment decisions – challenges for doctorsBMJ2003327741454254512958116

- LohASimonDWillsCEKristonLNieblingWHarterMThe effects of a shared decision-making intervention in primary care of depression: a cluster-randomized controlled trialPatient Educ Couns200767332433217509808

- JoostenEADeFuentes-MerillasLde WeertGHSenskyTvan der StaakCPde JongCASystematic review of the effects of shared decision-making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health statusPsychother Psychosom200877421922618418028

- GrangerALFehnelSEHogueSLBennettLEdinHMAn assessment of patient preference and adherence to treatment with Wellbutrin SR: a web-based surveyJ Affect Disord2006902–321722116360216

- GillissenALechelerJBronchial asthma: a comparison of the doctor’s assessment and the patient’s opinionDtsch Med Wochenschr200412910484489 German.14986236

- EmkeyRKoltunWBeusterienKPatient preference for once-monthly ibandronate versus once-weekly alendronate in a randomized, open-label, cross-over trial: the Boniva Alendronate Trial in Osteoporosis (BALTO)Curr Med Res Opin200521121895190316368038

- HaynesRBSackettDLGibsonESImprovement of medication compliance in uncontrolled hypertensionLancet1976179721265126873694

- LoganAGMilneBJAchberCCampbellWPHaynesRBWork-site treatment of hypertension by specially trained nurses. A controlled trialLancet1979281531175117891901

- HaslbeckJWSchaefferDRoutines in medication management: the perspective of people with chronic conditionsChronic Illn20095318419619656813

- ReginsterJYRabendaVNeuprezAAdherence, patient preference and dosing frequency: understanding the relationshipBone2006384 Suppl 1S2S616520104

- Carnaby-MannGCraryMPill swallowing by adults with dysphagiaArch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg20051311197097516301368

- IckovicsJRMeislerAWAdherence in AIDS clinical trials: a framework for clinical research and clinical careJ Clin Epidemiol19975043853919179096