Abstract

Studies have found that physician–patient relationships and communication quality are related to medication adherence and outcomes in HIV care. Few qualitative studies exist of how people living with HIV experience clinical communication about their self-care behavior. Eight focus groups with people living with HIV in two US cities were conducted. Participants responded to a detailed discussion guide and to reenactments of actual physician–patient dialogue about antiretroviral adherence. The 82 participants were diverse in age, sex, and ethnicity. Most had been living with HIV for many years and had stable relationships with providers. They appreciated providers who knew and cared about their personal lives, who were clear and direct about instructions, and who were accessible. Most had struggled to overcome addiction, emotional turmoil, and/or denial before gaining control over their lives and becoming adherent to medications. They made little or no causal attribution for their transformation to any outside agency, including their providers. They generally saw medication adherence as a function of autonomous motivation. Successful coping with HIV with its prevalent behavioral comorbidities, stigma, and other challenges requires a transformation of identity and internalization of motivation to maintain health. Effective methods for clinicians to support such development are needed.

Background

Talcott ParsonsCitation1 1950s-informed view of the patient as essentially passive and dependent, and the presumption that the physician’s technical competence and beneficence are unquestionable, came under growing criticism in later decades.Citation2 By the 1980s, “patient-centered care,” defined by Lipkin et al as treating the patient “as a unique human being with his [sic] own story to tell,”Citation3 became a widely accepted ideal. Increased interest in models called shared decision-makingCitation4 or concordanceCitation5 since the late 1990s represents an effort to truly redefine the relational goal as agreement between physicians and patients about whether, when, and how medicines are to be taken, via discussion that includes and respects the beliefs and wishes of the patient.Citation6 A related ideology of “patient empowerment” in chronic disease emerged in parallel from broader intellectual and social movements.Citation7,Citation8

Prior to 1996, there was no effective treatment for HIV, and the disease was considered inevitably progressive and ultimately fatal in all but exceptional cases. With the advent of highly active antiretroviral (ARV) therapy however, HIV has become a chronic but manageable illness.Citation9,Citation10

In this context, there is strong evidence that communication behaviors of health-care providers matter not only for patient satisfactionCitation11–Citation14 but also for adherence to medication regimens and other provider recommendationsCitation15 and health outcomes. Patients who report being treated with dignity are more satisfied and likely to receive optimal preventive care,Citation16 and those who report that their provider demonstrates “whole-person knowledge” are more likely to adhere to therapy.Citation17

Specific to HIV infection, Bakken et al reported a positive association between patient engagement with the health-care provider and adherence to therapy.Citation18 In a cross-sectional analysis of 554 patients taking ARVs for HIV in 22 outpatient practices, Schneider et al reported that six of seven patient–provider relationship-quality variables were significantly associated with adherence.Citation19 Similarly, Beach et al found that a single item measuring the essence of patient-centeredness – the patient’s perception of being “known as a person” – is significantly and independently associated with receiving ARV therapy, adhering to the therapy, and having undetectable serum HIV RNA.Citation20

Because adherence to ARV medications is such an important health-related behavior for many HIV-infected individuals, and therefore an important topic of communication in visits with health professionals, several studies have focused directly on the quality of patient–physician dialogue about medication adherence. For example, in previous work we found that physicians typically adopt a directive style in addressing nonadherence by their patients with HIV, as indicated by such measures as the use of many directive utterances, physician verbal dominance, and few patient expressive utterances.Citation21 In another observational study, Barfod et al found that physicians are reluctant to raise the issue of ARV adherence, and that discussions when they do occur in routine HIV-care visits are often cursory.Citation22 Finally, in a qualitative study, patients perceived physicians as lecturing or scolding them about adherence, reported concealing their nonadherent behavior at future visits, and in some cases reported discontinuing clinic attendance or stopping medication taking altogether as a result.Citation23

The latter study is the only one we have found that focuses on patients’ experiences and views about communication with their providers regarding HIV adherence. Therefore, as formative research for a pilot intervention study to improve provider communication skills about ARV adherence, we conducted focus groups with people living with HIV to elicit their perspectives on their own experiences with coping and adjusting to the HIV diagnosis, medication adherence, their relationships with their HIV providers, and the ways in which their HIV providers may contribute to their decisions and behavior surrounding ARV treatment.

Methods

We conducted four focus groups of people living with HIV in each of two East Coast cities – one in New England, one in the mid-Atlantic region – for a total of eight groups. This number of groups enabled us to remain within budgetary limitations while stratifying the groups according to patient characteristics we believed would be important sources of variation (see below). We developed the discussion guide based in part on interview guides the first author (MBL) had used in previous studies concerning medication adherence,Citation24,Citation25 adapted to meet the specific objectives of this study. MBL then administered the draft interview guide to three subjects recruited through flyers distributed at a local AIDS service organization. Based on this experience, we modified the guide for better flow and to incorporate some issues that we discovered to have salience in the pilot interviews.

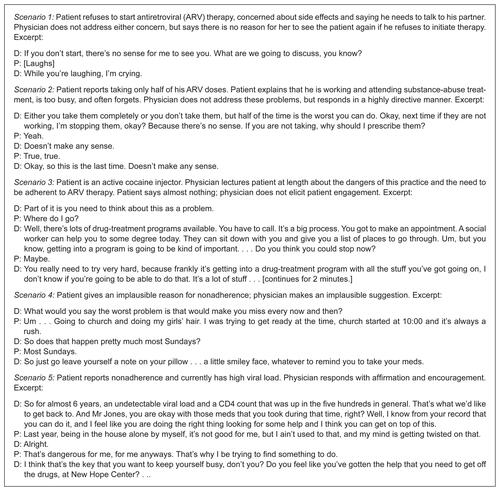

The discussion guide included psychosocial and treatment history of living with HIV, relationship with current HIV provider, and experiences discussing ARV adherence with providers. We also played re-creations by actors of portions of actual physician–patient dialogues about ARV adherence, taken from data collected for other studies (audio recordings of the scenarios can be found at http://research.brown.edu/myresearch/Michael%20Barton_Laws) and asked participants to evaluate them. We selected the audio prompts (see ) to include contrasting interaction styles, including providers who were confrontational, collaborative, and directive; and contrasting issues including refusal to initiate ARV therapy, active injection cocaine use, regular nonadherence (not taking morning doses), and reported occasional nonadherence.

We recruited participants at the New England site (Site 1) through flyers at local AIDS service organizations and at an infectious disease clinic. The groups at Site 1 were completed before we began recruitment at the mid-Atlantic Site 2. At Site 2, all participants were recruited with flyers or by a research assistant at a large academic HIV-specialty clinic. We screened potential participants by telephone to ensure that they met the eligibility criteria of being engaged in medical care and having prescriptions for ARVs. Because the volunteers were diverse in sex, age, ethnicity, and level of education, we did not have to make further efforts to achieve diversity. The groups were generally representative of the demographics of the HIV epidemic in the respective cities by sex and ethnicity (see Results).

Groups at Site 1 were stratified by education level, with participants in two of the groups selected to have some education beyond high school, and in the other two to have high school education or less. Because we recognized the importance of substance abuse and addiction history from our experience at Site 1, at Site 2 we stratified by salient substance-abuse history, and cross-stratified by recent history of recognized nonadherence or elevated viral loads. This constitutes a limited implementation of theoretical sampling, in that we modified our respondent selection criteria in response to initial observations.Citation26

MBL facilitated all the groups. We played the audio prompts in the final portion of the discussion, so as not to contaminate people’s reflections on their own interactions with providers. Discussions lasted for approximately 90 minutes. Participants were compensated $50 for their time and given lunch or snacks depending on the time of day. This study was approved by the institutional review board of each participating institution.

Audio recordings of the groups were transcribed by a professional service. Members of the research team then reviewed and corrected the transcripts prior to analysis. After we had completed the groups, MBL discussed his impressions with the other authors, and we agreed on a general approach to analysis. Another author (TT) had been present at all group discussions at Site 1, while MG was present at all group discussions at Site 2. They concurred with the overall impressions. MBL then conducted open coding of the transcripts using Atlas.ti software (Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany) to identify common narrative elements and themes. In particular, we noted the importance of substance abuse and other psychosocial problems in participants’ narratives of their treatment and adherence history, and the centrality of narratives of personal transformation as affecting their relationships with their providers. Another author (TB) then repeated the open coding, beginning with a list of the codes identified by MBL but blinded to where they had been applied. We found that the decisions were a close match and appeared exhaustive of the substantive material.

Based on these codes, we then organized the concepts into thematic categories and identified patterns and contrasts within them, through discussions among the coders and other authors. Finally, we met with a patient advisory committee, a group of six people living with HIV, recruited from Site 1 and from a clinical site in a neighboring state, and presented our preliminary results to them. This group is working with us closely on another study concerning explanatory models and treatment decision-making by people living with HIV. They reflected on our interpretations of the focus groups in light of their own experiences. This presentation incorporates their reactions and suggestions.

Results

Participants at Site 1 were ethnically diverse, comprising 14 African-American, 16 white non-Hispanic, eleven Latino, and seven “other” individuals, including Native Americans and people of mixed race. Of 34 participants at Site 2, all but three were African-American. About 40% of participants were female at both sites. Ages ranged from early 20s to 60s.

All but two participants, one at each site, reported having a physician as their primary HIV care provider. The other two principally interacted with nurse practitioners. Most participants had been living with HIV for more than 5 years, many for more than a decade. A few had been diagnosed within the past year or two. Several important themes emerged consistently at both sites; however, there were some differences with the higher-educated groups at Site 1, and participants at Site 2 were more likely to speak in religious, specifically Christian, terms.

Theme 1: qualities of satisfactory relationships with current providers

The overwhelming majority of participants reported very satisfactory relationships with their current providers, often using language of emotional attachment and friendship. Many were explicit about their provider knowing about their personal lives and struggles.

Well, my doctor, she’s brilliant. . . . She’s been really responsive to anything that would happen to me and even with my legal issues. . . . They were both [the doctor and social worker] just super. They remain the most important people. They remain very good friends of mine. (25-year-old male, immigrant from Russia)

That man will forever be a savior to me, ‘cause he saved me so many times, and I was so close so many times. We are very interactive; he wants to know . . . exactly what I do, exactly what I eat. (48-year-old male)

He’s compassionate, he’s a regular guy. He’s not intimidating, you know? You know how you get intimidated by your doctor? He just talks to you like he’s just a regular guy. (46-year-old female)

A noteworthy theme at both sites was appreciation for the provider being accessible. Some participants had a home-phone or a cell-phone number for their provider, or reported the provider being available promptly for exigent needs. People also valued broader features of accessibility, such as availability of nurses for telephone consultation.

My mother passed the 30th of last month and the only person I could talk to was my doctor. I called her at her house and she talked to me on the phone. I said damn, you the only doctor I ever had that I can call you at home and you will talk to me. (45-year-old female)

[M]e and him is great. He’s got my number. I got his number. I could call him for an emergency and talk to him, if he’s not busy. If he’s busy, he’ll call me back off his pager. I can talk to him about anything, sexual or health-wise, even some mental problems. (48-year-old male)

Subthemes included a few people who were recently diagnosed or had recently changed providers, who were still developing relationships with their providers and were not yet willing to evaluate them. Some reported less satisfactory or affirmatively unsatisfactory relationships with previous providers in other settings. There were also some complaints about hurried visits with current providers, and patients failing to get their agendas addressed on occasion.

Theme 2: stories of personal transformation

Most long-term survivors had gone through an initial period, lasting from months to years, of nonadherence, on-and-off adherence, or nonengagement in care, often but not always associated with active substance abuse. A few reported reacting to the initial diagnosis with relative equanimity, but most reported negative feelings, including anger or betrayal. An initial stage of denial or avoidance was common:

In the beginning, I was in denial. And I got it by sharing needles, that’s how. The health department also came and informed me of that. But with that I had other issues going on in my life because I take medication for major depression because just bad thing just has happened to me in my life . . . So in the beginning I ain’t wanted to believe that until I got sick. (mid-30 s male)

Okay, well, I found out in the 70s [sic], when I was young and acting crazy. . . . So after I found out, I just got real crazy, and I started taking all kinds of drugs and going on all kinds of dope and stuff. . . . And I really didn’t care. (64-year-old male)

I went through a hell of a lot of stuff, you know. . . . Of course I was a heavy drinker. And I taught school for 37 years but in the meantime was out in the street doing all – I was very promiscuous. My marriage broke – marriage went down the hole. . . . I had thought about committing suicide. (64-year-old male)

I would refuse to [take medication], ‘cause I stayed in denial. I said, I used to tell myself, “I got a different kind, . . . so I got a different strain.” You know, I can’t affect nobody ‘cause I got a different strain. (47-year-old female)

Substance abuse was commonly closely entangled with emotional distress and denial, but was sometimes described as a factor in not taking medication and not engaging in care in its own right.

I used to miss because I would drink . . . And then I found myself, say like when I was drinking heavy, real heavy I wouldn’t take no medicine and then I’d break down. . . . Only thing I wanted to do was drink, drink, and drink. (45-year-old male)

[Another participant] touched me over here when he said “a slow suicide.” That’s what I’m doing, I guess, because I stopped taking my medicine when I was using. I was dibbing and dabbing. I always thought if I dib and dab and didn’t get a habit, a heroin habit, I’d be okay, in my little mind. Well that’s not so. (55-year-old female)

I mean last year I was strung out on heroin . . . I was about 140 pounds, sweating all the time, not taking any meds, ‘cause my experience has been if I’m using I don’t take meds at all, ‘cause if you skip doses and take them sporadically then you become resistant to them, and I’ve already done that a couple of times. (50-year-old male)

Most participants who had gone through such struggles described abrupt experiences of change: decisions to start taking care of themselves and to live. Some framed these experiences in religious terms, but otherwise nearly all credited themselves with an autonomous choice, and gave little or no indication that outside influences were important.

And eventually, you know, I came to grips with myself and I – you know, I believe in God, so I had a higher power to go to – and I asked the Lord to bless me and take care of me, and He has. So my viral load is undetectable, my CD count’s over 600 too. And I’ve been taking the medication for a while. (56-year-old male)

So, I wasn’t out of the hospital 5 weeks and I was right back at it again, running wild again. And I gets locked up, every time I gets locked up I let the doctors know straight off that I’m HIV, and they give me what I have to do. I start taking my medication and everything, but every time I get released I’m out there running again. Then I fell out down here on [a street corner] and went into a coma. I was gone in the coma for two and a half days. When I fell out it Saturday when I woke up it was two in the evening, and by the grace of God that’s why I’m here today, and I’ve been clean ever since. (50-year-old male)

Then I went through acceptance, because I told myself I was not going to perish, or let this, you know, affect my accomplishments, because I still wanted a lot to do. And it reinforced my love for Jesus, because I know he loves me and I see that every day. Went back to school, went and got my GED, went through drug treatment, completed that. Now I work full-time. (45-year-old male)

And I really didn’t care until one day I went to lay down, and I started to sinking in the bed, going deeper and deeper. And I said, “Oh God, help me.” So God let me come up, and I saw I was going to hell. . . . So I got saved, and had the Lord in my life. . . . Went to cooking school, and went to clean up, janitor, got a certificate for that. . . . And life just changed. . . . and after that, I started taking the medicine and start going to doctors. (52-year-old male)

So I have been through some turmoils with my HIV, you know. I guess at one point I just didn’t want to take my medicine. I used every excuse in the world not to take it. . . . So, you know, I went as far as my T-cells down to six, and that’s a sight you don’t even want to see. So, you know, I just refused to keep living like that, and I don’t have to. (53-year-old female)

As a matter of fact I just started my medication, like, 4 months ago and I’ve been doing very well with it. You know, I used to make appointments all the time when I wouldn’t keep them. You know, and then for some reason I just started worrying more about myself. (45-year-old male)

Theme 3: relationship with the provider during times of struggle

A few participants did suggest that continued support from their providers was a factor in making or sustaining change. In any event many were appreciative that their provider stayed with them during their struggles.

[The doctor] says, “You’re changing. The longer you’re out, the more you’re changing.” I said, “Well, I’m trying to get away from that, you know that.” I still in my own prison, let’s get that straight, but I’m trying to get out of it, you know, and he sees it. I wouldn’t trade him. (50-year-old male)

That was my purpose was to keep on using until I die, but the [study] referred me to the clinic. And by me being a naive patient they got me into [an adherence support project] for people like me, naive about HIV and the lifestyle. Because I always had a thing about medicine. Gradually I got on the medicine, and got undetectable viral load. (57-year-old male)

But my medical providers, they didn’t give up on me and they wouldn’t let me give up on myself, you know? ‘Cause I had a son to bring through. I didn’t want to see his life ended at 8 years old. . . (53-year-old female)

And when I got sober, that’s when I realized I was bipolar, I was manic-depressed, I had posttraumatic stress from a lot of trauma in my life. And that’s what made me – you know, being around my doctors, being around doctors that cared, you know, that when I told that I might be – I’m feeling really down or something and they would always say, “Are you suicidal or do you feel that way?” and I’d be like, “Lock me up if I tell you.” (47-year-old female)

Theme 4: present adherence to medication regimens

All said they would disclose nonadherence to their current providers. Many noted that the provider could tell anyway from pharmacy refill records and lab tests. However, many participants said they did not necessarily disclose in the past when they had not committed to treatment. Most reported diligent current adherence. Some were adherent in spite of difficulties, because they believed it was necessary to preserve life and health:

The other day I was like, “I’m so sick of taking this shit. I’m not taking this medicine today.” And before the day was over I took it ‘cause I know it’s helping me live. (47-year-old male)

You get scared and then once you get over 40 and start turning, like almost 50 . . . you gonna take anything you can to try to live. (47-year-old female)

The very thought of missing a dose is uncomfortable because the science now says if you take medicine you’ll stay healthy, if you don’t there’s a possibility you’ll get sick. (54-year-old male)

Others reported that taking their medications was intrinsically satisfying:

R: What I like to do, I like to go dancing, right, and then I like to take my meds on a regular basis.

Moderator: You actually enjoy that?

R: I love it, yes. (52-year-old male)

I’m doing pretty good on mine too. I enjoy taking my medication. I have fun when I take it. That’s, I’m saying that’s the only way that I could really put it in. Like I be actually taking my medication and making myself be happy. I’m serious. (51-year-old female)

There were subthemes associated with current less-than-perfect adherence. In spite of their good current relationships and trust for their providers, not all respondents said they always follow the provider’s recommendations. Two said that they do not take their ARVs when they drink alcohol, even though their provider had said they should, believing that the combination is “too strong” for their bodies. Another takes days or weekends off to give his body “a break” from the medicines. Yet another had decided to stop altogether for some time, until her T-cells are depleted, with her doctor’s knowledge but disapproval.

Reaction to audio prompts

In response to the audio prompts (see for scenarios), participants overwhelmingly made statements to the effect that they appreciated clarity and directness from the providers. However, their reactions to confrontational and directive style were mixed. Positive reactions were based on the perceived accuracy of the content of the provider’s message.

She’s been there for him and she’s letting them know exactly what the consequences are. . . . And it’s up to you to change, make a change, you know to help yourself. So I think she’s right for being hard. (56-year-old male, Scenario 2)

This looks like to me that she’s been talking to her patient about this for a numerous amount of time. . . . She’s seeing that fact in the history that he’s going down below 200 and the doctor getting upset about that is very, very understandable. They’re in this business to save lives, not lose lives. . . . I don’t think she was rude, I think she was giving him tough love. (30-year-old male, Scenario 1)

If I was his doctor I would have said to him, “Well listen here young man, here’s the one side effect that not taking your medication will give you and you’re going to get that side effect no matter how you slice it. Death, imminent death. . . .” I would have went it and shocked him to the point where it’s like let me really think about what my life is and where it’s going. (57-year-old male, Scenario 1)

Several participants made it explicit that they were endorsing the accuracy of the communication, not necessarily its effectiveness in promoting behavior change:

Well, I think it’s like a decision that we have to make for our own selves, just like no matter how much the doctor nags you or persists on you need to stop using and you need to take your medication, we have to want to do it. We have to want whatever it is that we’re going to do. (47-year-old female, Scenario 1)

Your doctor can tell you to do this and the doctor can tell you that, but you have to go and do your part, too. You’re accountable for taking your medicine, taking it on time. You’re accountable for this. But if you don’t do that, then you and your doctor not going even – you wasting his time, and you’re wasting your time. (64-year-old male, Scenario 2)

Damn, I should have listened to that woman. She just was talking and it went right past my head. (Scenario 3)

In the groups stratified by level of education, these positive responses to physicians’ confrontational and directive style were characteristic of the lower-educated groups. Participants in the higher-educated groups were much more critical. In the groups stratified by substance-abuse history, we could not make a similar distinction, but did note that responses within the group with a substance-abuse history but recent good adherence were mostly supportive of the confrontational style, with the exception of a single participant.

Some participants who objected to these examples focused on the manner in which the physician spoke:

I don’t really think it was professional at all, like the way she’s talking like to that client like if she’s talking to her kid or something. (27-year-old male, Scenario 1)

Because of the way – the tone of her voice and what she was saying to him. She basically wanted to give him tough love, but she didn’t know how. (30-year-old male, Scenario 2)

I’m sorry, but that doctor just seemed really – she was informative, but I felt like she kept going on going back and around in circles, and like she was trying to get a reaction out of the patient. But I think she sounded genuinely concerned about the patient, but that she didn’t know how to actually express those feelings in a professional manner . . . She just sounded like she was pointing her finger while she was saying it. (30-year-old male, Scenario 2)

Me and my doctor, we don’t have that kind of attitude, talk like that. To see this like that, grrr. We goof, like you know what I mean? We don’t – she don’t talk down to me like that. (52-year-old male, Scenario 2)

Scenario 1 included the physician threatening not to see the patient if he didn’t start ARV therapy. Some respondents reacted strongly to this tactic:

When I started with my doctor, you know, he told me, “If you don’t think it’s doing any good, well, then you stop.” But he never say he’d stop seeing me, you know? . . . So I think a doctor should . . . be more professional, let you know what the side effects are . . . because sometimes the doctor himself, if your side effects are too strong, he’ll take you off, but you need to discuss that. (58-year-old male)

Well she wasn’t professional in that she didn’t get the guy to explain the options. She’s calling him avoidant and that’s a bit offensive. She should be encouraging and explain what good things would happen with the medicine. . . . She’s saying I don’t want to see you if you don’t start the medicine. That is threatening and it’s blackmail. (54-year-old male)

I didn’t like the ultimatum. Like the first scenario, I didn’t like the ultimatum. Doctor didn’t really discuss, help this person to understand why he needs to take the drugs. (54-year-old male)

One objected to the same physician’s tactic of accusing the patient of hurting her feelings:

You know, that she said, “While you’re laughing I’m crying,” that’s – I mean that’s kind of a stretch. I mean I know my doctors have felt that way, ‘cause I seen it in their eyes, but for somebody to say that, it’s almost like their happiness depends on you taking your meds. I’m going through enough right now. I have plenty to deal with. (48-year-old male)

Scenario 4 involved the patient saying that she missed doses on Sunday mornings because she was busy getting her children ready for church. Participants universally perceived that this was an implausible excuse that the doctor had failed to see through. In response to Scenario 1, several also felt the doctor had failed to accurately diagnose the patient’s reason for not initiating treatment. They commented on the physicians’ failure to ask open questions and understand what was really happening with the patients, or to provide essential information.

But first and foremost they should tell you what is gonna be the side effects if you don’t do it. It gives the chance first to say – when you’re silent you think, because I’ve done it. And you don’t say nothin’. So I see that as a good thing because if it seems like he’s prodding me too much, then I might get offensive and like [makes noise], you know? (68-year-old male)

I noticed many of the monologues of this doctor, they ended with these multiple questions that I personally would not be able to answer. I would feel confused like which question I would have to answer now. (25-year-old male)

Discussion

With few exceptions, these participants, most of whom had been living with HIV for many years, became adherent to medication regimens and medical appointments only after undergoing personal transformations that represented incorporation of illness identity, acceptance of the reality of their condition, and a new or renewed sense of agency, including a will to live. They offered little insight into any external factors, including personal or professional relationships, that may have contributed to these transformations, which they experienced as sudden and unexpected.

While there may be other vocabularies and theoretical frameworks for interpreting these stories, a widely employed framework is identity theory. Sociological studies of how identity is affected by and reformulated in the course of chronic illness emerged, beginning with general treatments in the early 1980s,Citation27,Citation28 and continuing with numerous studies in specific conditions. This literature is briefly summarized in a recent article that explores identity reformulation in chronic illness in relation to the concept of patient empowerment,Citation29 and in another specifically concerning identity incorporation in HIV/AIDS.Citation30 In the language of identity theory, the “self” is composed of many identities,Citation31 which correspond to various roles and relationships, eg, a person’s identities might include student, athlete, a son, and African-American. More “salient” identities are those that people are likely to present in a wider variety of contexts. Within this framework, the “self” is relatively stable, but must abandon some identities and incorporate new ones over time.

Diagnosis with a chronic disease presents several challenges to identity. It typically requires new behaviors and activities, such as regularly taking medications and seeing specialist physicians. It may force changes in work or other established roles, including sexual and romantic relationships. In the case of HIV, the diagnosis also carries stigma and presents problems of concealment or disclosure. Changes in expectation for longevity and future health also may strike at the very heart of the self-system. For many people with HIV, there are additional layers of complexity related to identity, such as substance abuse or addiction, criminal justice involvement, mental illness, and sexuality, all of which may need to be confronted in order to successfully manage living with HIV.

Studies of identity reformation in the highly active ARV therapy era generally find that while some people readily accept the diagnosis and easily enter into treatment, others experience initial reactions of shock, anger, despair, or denial, as most of our participants reported. For the latter group, accepting the new reality and undertaking the changes needed to survive in good health may take a long time.Citation30,Citation32,Citation33 Indeed, people with serious substance-abuse problems may ultimately come to see the acceptance of their diagnosis as the impetus for positive changes in their lives.Citation34 The transformation is often experienced, or at least recalled, as a sudden event, which may be interpreted as a religious experience or conversion.Citation35,Citation36

In the vernacular, people speak of “hitting bottom,” and these transformations may also be seen as simply a reaction to the fear of death. However, these are not explanations. Our respondents often had lengthy histories of marginalized and traumatic lives, including homelessness, incarceration, victimization, and poor health, including repeated hospitalizations; or else they simply lived in denial of being HIV+ for a time and tried to live as though they were not. They did not point to anything unique or dramatically different about their circumstances at the time they experienced their transformations; the one or two who had brushes with what may have been imminent death had been there before, and still returned to their old ways. Rather, people describe coming to terms with their situation and resolving to live differently: an internal change of mysterious origin. The vocabulary of identity reformation does not try to explain why it happens when it does, but rather to describe what it is: a change in both internal motivational structure, and self-presentation to the world.

While our respondents did not credit the physician–patient relationship with their epiphanies, they were appreciative that their providers appeared to care about their well-being even while they were not engaged in effective self-care. They valued clarity and directness on the part of health-care providers about the consequences of medication nonadherence as a sign of caring. Some endorsed confrontational, scolding, or coercive tactics by physicians toward people in their former state, but they did not claim that these tactics were effective. Rather, they justified them in essentially moral terms: that the physician expressed a well-deserved judgment, one that they also made about their former selves.

Presently, they view their relationship with their physicians as a partnership. Since they share the commitment to effective treatment, they are comfortable disclosing any of their failures, because they expect the physician to be helpful in achieving better adherence in the future, or alternatively to negotiate a plan which is mutually acceptable for treatment delay or interruption, or a harm-reduction approach to drug use, if need be.

We are particularly drawn to the discussion by Aujoulat and colleaguesCitation29 who conclude that the incorporation of illness identity and achievement of self-agency in chronic illness correspond to what is called intrinsic motivation in the self-determination theory (SDT) of Deci and Ryan.Citation37,Citation38 These include competence, and self-determination or autonomy: “Studies on SDT and intrinsic motivation in relation to chronic illness and adherence have shown the importance of self-determined or autonomously regulated goals on health outcomes.”

A more precise statement might refer to self-determined extrinsic motivation, since “intrinsic” motivation refers to those behaviors that are satisfying in themselves, while taking medication is normally a goal-directed behavior. SDT posits a continuum of extrinsically acquired motivation, which ranges from fully external regulation (ie, response to contingencies controlled by others, such as payment or punishment), to introjected regulation, where the person has partially internalized the contingencies (ie, feels self-esteem or shame depending on compliance), to identification, in which the person values a goal that motivates the behavior. The most self-determined, autonomous level of extrinsic regulation is integrated regulation, in which behavior is sustained because the goal is consistent with core values or goals. Intrinsically motivated or fully autonomous regulation in SDT is seen as based on intrinsic human drives for competence, autonomy, and relatedness with others. Fully autonomous behaviors are engaged in for their own sake, with no sense of coercion, as in the case of our respondents who said they actually enjoyed taking their pills.

Behaviors toward the external end of the spectrum are typically engaged in less consistently, are not inherently enjoyable, and indeed may produce conflicted or negative feelings. More autonomously motivated behaviors are engaged in consistently, sustained over time, and produce satisfaction. In our participants’ stories, we perceive an initial period during which their motivation for ARV adherence was purely external – they were warned of dire consequences if they failed to adhere, but this did not suffice to produce consistent self-care behavior. In addition, it sometimes produced a conflicted relationship with their health-care providers.

Their stories of transformation can be seen as the integration of regulation, in which people set new goals for a more rewarding life and acquired a more autonomous motivation for medication adherence in furtherance of those goals. Ultimately, for some, medication-taking becomes “identified” or even fully “autonomous,” as a demonstration of competency and self-control, and a manifestation of alliance with their health-care providers and significant others, ie, relatedness. As we have seen, some reported regular adherence because it was consistent with their goal of maintaining their health, representing identified or integrated regulation, while a small number expressed fully intrinsically motivated behavior, saying they actually enjoyed taking their pills.

Our respondents did not say that their physicians actively helped them to achieve these states. In fact, they offered little if any insight into why their motivational state changed when it did. It may be that providers who are trained in motivational interviewing – a method developed to enhance autonomous regulation – could have contributed more to these transformations.Citation39 Because we did not collect any information about participating physicians’ training in motivational interviewing, we can only speculate about such effects. In any event, their physicians’ patience and perseverance were eventually rewarded, as these patients ultimately came to autonomous treatment regulation one way or another, and appreciated their physicians having stood by them along the way.

This study has several limitations. We studied participants who were engaged in care, in urban areas of the East Coast; attitudes may differ regionally or for those not engaged in care. There is also potentially a survivor bias, as people who do not have self-care epiphanies may not be alive. Patients lacking the communications skills or self-confidence to volunteer for a focus group may be different from those who do participate, and there may be various other reasons why people would not participate, such as having demanding work or dependent care responsibilities. While our participants were men and women with a broad range of socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and clinical backgrounds, these observations only show that some people living with HIV undergo such transformations; the prevalence of such experiences is unknown.

Becoming someone who can effectively manage HIV can be a lengthy process that includes accepting the reality of an HIV diagnosis, integrating the new identity and challenges that come with it, and often overcoming substance-use disorders and difficult psychosocial circumstances that interfere with HIV treatment. Many people do not engage effectively in treatment for some time, but ultimately reform their identity so that they can. Their expressed preferences about provider communication may be informed by their current SDT stage and their memories of how they were and what they needed to hear in previous stages. Providers must take a long-term view when patients are not adherent or are not consistently engaged in treatment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a developmental award from the Lifespan/Tufts/Brown Center for AIDS Research (5P30AI042853); and by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH, award #1R34MH089279-01 A1). Dr Wilson was supported by a K24 from NIMH (2K24MH092242). The views expressed here are those of the authors, and no official endorsement by the US Department of Health and Human Services is intended or should be inferred. Thanks also to Tanita Woodson, and Renee Shield, PhD, for helpful comments.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ParsonsTThe Social SystemGlencoe (NY)The Free Press1951

- ConradPThe experience of illness: recent and new directionsRothJACPResearch in the Sociology of Health Care: The Experience and Management of Chronic IllnessGreenwich (CT)JAI Press1987

- LipkinMQuillTENapodanoRJThe medical interview: a core curriculum for residencies in internal medicineAnn Intern Med198410022772846362513

- MakoulGClaymanMLAn integrative model of shared decision making in medical encountersPatient Educ Couns200660330131216051459

- O’ConnorAMRostomAFisetVDecision aids for patients facing health treatment or screening decisions: systematic reviewBMJ1999319721273173410487995

- MarinkerMShawJNot to be taken as directedBMJ2003326738534834912586645

- CrossleyM“Sick role” or “empowerment”? The ambiguities of life with an HIV positive diagnosisSociol Health Illn1998204507531

- HolmstromIRoingMThe relation between patient-centeredness and patient empowerment: a discussion on conceptsPatient Educ Couns201079216717219748203

- PalellaFJJrDelaneyKMMoormanACDeclining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study InvestigatorsNew Engl J Med1998338138538609516219

- LedergerberBEggerMOpravilMClinical progression and virological failure on highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 patients: a prospective cohort study. Swiss HIV Cohort StudyLancet1999353915686386810093977

- KaplanSHGandekBGreenfieldSRogersWWareJEPatient and visit characteristics related to physicians’ participatory decision-making style. Results from the Medical Outcomes StudyMed Care19953312117611877500658

- RoterDLStewartMPutnamSMLipkinMJrStilesWInuiTSCommunication patterns of primary care physiciansJAMA199727743503569002500

- BertakisKDRoterDPutnamSMThe relationship of physician medical interview style to patient satisfactionJ Fam Pract19913221751811990046

- LevinsonWRoterDLMulloolyJPDullVTFrankelRMPhysician-patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeonsJAMA199727775535599032162

- HallJARoterDLKatzNRMeta-analysis of correlates of provider behavior in medical encountersMed Care19882676576753292851

- BeachMCSugarmanJJohnsonRLArbelaezJJDugganPSCooperLADo patients treated with dignity report higher satisfaction, adherence, and receipt of preventive care?Ann Fam Med20053433133816046566

- SafranDGTairaDARogersWHKosinskiMWareJETarlovARLinking primary care performance to outcomes of careJ Fam Pract19984732132209752374

- BakkenSHolzemerWLBrownMARelationships between perception of engagement with health care provider and demographic characteristics, health status, and adherence to therapeutic regimen in persons with HIV/AIDSAIDS Patient Care STDS200014418919710806637

- SchneiderJKaplanSHGreenfieldSLiWWilsonIBBetter physician-patient relationships are associated with higher reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infectionJ Gen Intern Med200419111096110315566438

- BeachMCKerulyJMooreRDIs the quality of the patient-provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV?J Gen Intern Med200621666166516808754

- WilsonIBLawsMBSafrenSAProvider focused intervention increases HIV antiretroviral adherence related dialogue, but does not improve antiretroviral therapy adherence in persons with HIVJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr201053333834720048680

- BarfodTSHechtFMRubowCGerstoftJPhysicians’ communication with patients about adherence to HIV medication in San Francisco and Copenhagen: a qualitative study using grounded theoryBMC Health Serv Res2006615417144910

- TugenbergTWareNCWyattMAParadoxical effects of clinician emphasis on adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDSAIDS Patient Care STDS200620426927416623625

- LawsMBWilsonIBBowserDMKerrSETaking antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: learning from patients’ storiesJ Gen Intern Med2000151284885811119181

- RifkinDELawsMBRaoMBalakrishnanVSSarnakMJWilsonIBMedication adherence behavior and priorities among older adults with CKD: a semistructured interview studyAm J Kidney Dis201056343944620674113

- GlaserBStraussADiscovery of Grounded TheoryChicagoAldine1967

- BuryMChronic illness as biographical disruptionSociol Health Illn19824216718210260456

- CharmazKLoss of self: a fundamental form of suffering in the chronically illSociol Health Illn19835216819510261981

- AujoulatIMarcolongoRBonadimanLDeccacheAReconsidering patient empowerment in chronic illness: a critique of models of self-efficacy and bodily controlSoc Sci Med20086651228123918155338

- BaumgartnerLMThe incorporation of the HIV/AIDS identity into the self over timeQual Health Res200717791993117724104

- SerpeRTStability and change in self: a structural symbolic interactionist explanationSoc Psychol Q19875014455

- TsarenkoYPolonskyMJ‘You can spend your life dying or you can spend your life living’: identity transition in people who are HIV-positivePsychol Health201126446548320945254

- BaumgartnerLMDavidKNAccepting being poz: the incorporation of the HIV identity into the selfQual Health Res200919121730174319949222

- MosackKEAbbottMSingerMWeeksMRRohenaLIf I didn’t have HIV, I’d be dead now: illness narratives of drug users living with HIV/AIDSQual Health Res200515558660515802537

- KremerHIronsonGEverything changed: spiritual transformation in people with HIVInt J Psychiatry Med200939324326219967898

- IronsonGKremerHSpiritual transformation, psychological well-being, health, and survival in people with HIVInt J Psychiatry Med200939326328119967899

- DeciELRyanRMA motivational approach to self: integration in personalityNebr Symp Motiv1990382372882130258

- DeciELRyanRMThe support of autonomy and the control of behaviorJ Pers Soc Psychol1987536102410373320334

- MarklandDRyanRMTobinVJRollnickSMotivational interviewing and self-determination theoryJ Soc Clin Psychol2005246811831