Abstract

Background:

Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) may suffer from concomitant pain symptoms. The aim of this study is to determine whether the presence of painful physical symptoms (PPS) influences quality of life when taking into account baseline depression severity.

Methods:

Patients with a new or first episode of MDD (n = 909) were enrolled in a 3-month prospective observational study in East Asia. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Clinical Global Impression-Severity score, Somatic Symptom Inventory, and EuroQoL questionnaire-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) and EQ-Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS) were assessed at baseline and 3 months’ follow-up. The presence of PPS was defined as a mean score of ≥2 on the Somatic Symptom Inventory pain-related items. Regression analyses determined predictors of quality of life at 3 months, adjusting for age, sex, depressive symptoms, overall severity, and quality of life at baseline.

Results:

PPS were present (PPS+) at baseline in 52% of patients. During the 3-month follow-up, EQ-VAS scores improved from 47.7 (standard deviation [SD] 20.6) to 72.5 (SD 20.4), and EQ-5D improved from 0.48 (SD 0.34) to 0.80 (SD 0.26). At 3 months, mean EQ-VAS was 66.4 (SD 21.2) for baseline PPS+ patients versus 78.5 (SD 17.6) for baseline PPS− patients, and mean EQ-5D was 0.71 (SD 0.29) versus 0.89 (SD 0.18). PPS+ at baseline was a significant predictor of quality of life at 3 months after adjusting for sociodemographic and baseline clinical variables.

Conclusion:

The presence of painful physical symptoms is associated with less improvement in quality of life in patients receiving treatment for major depression, even when adjusting for depression severity.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common and debilitating condition that rates among the highest causes of disability in the world.Citation1 The average 12-month prevalence of MDD has been estimated to be around 5.5% in ten high-income countries, and 5.9% in eight low- to middle-income countries.Citation2 The diagnostic criteria for MDD is mainly based in psychological and vegetative symptoms. However, other somatic and pain symptoms are frequent in these patients.Citation3 Moreover, somatic or pain symptoms are usually the main reason for a depressed patient’s initial visit to the primary care physician.Citation4

Painful physical symptoms (PPS), including headaches, stomach pain, back pain, and vague, poorly localized pain, are frequent in patients with depression.Citation4–Citation8 The presence of pain predicts a longer time to remission,Citation9 and the resolution of these physical symptoms is a strong predictor of full remission.Citation10 Failure to address the physical symptoms associated with depression may compromise the overall remission rate.Citation7,Citation11,Citation12 Also, patients who achieve remission but continue to suffer from residual physical symptoms may have a greater risk of clinical relapse.Citation13

Patients with depression rate their quality of life (QoL) lower than the general population or lower than patients with other chronic diseases, such as diabetes, arthritis, or cardiovascular disease.Citation14–Citation17 Although QoL improves after starting antidepressant medication, it remains low compared to healthy controls,Citation18 and several depression-related variables, including initial severity of depression, have been associated with worse QoL outcomes in depressed patients.Citation19 Coexisting pain symptoms are also known to be associated with poorer outcomes, including worse patient-reported QoL, lower productivity, and increased health care utilization.Citation20

The association between depression and pain is complex, and the underlying mechanisms are not yet fully understood, but they are known to share a common neurochemical pathway such that both pain and depression are influenced by serotonin and norepinephrine.Citation20,Citation22–Citation24 It has been suggested that the differential clinical phenomenology in depression is caused by dysfunction of specific neural pathways modulated by serotonin and norepinephrine.Citation25 This seems to be true for both psychological and somatic symptoms of depression.Citation24 A key clinical question is whether physicians need to take into account pain symptoms when diagnosing or treating a patient with major depression. If both pain and mood symptoms in depression have a common mechanism, then treating mood symptoms alone would be sufficient and pain would have a negligible impact on outcomes. Conversely, if pain and mood symptoms have different underlying mechanisms, pain symptoms may not impact outcomes through depression severity, hence, this should be taken into account in the treatment of the patient.

The aim of this observational study of Asian patients treated for an acute episode of MDD is to examine whether the presence of PPS influences patient self-reported QoL even when adjusting for the severity of depression.

Methods

Study design and participants

This 3-month, prospective, observational study in the psychiatric care setting enrolled 909 patients from 30 study sites across six East Asian countries and regions: China (Mainland), Hong Kong, Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, and Taiwan. Patients were recruited from June 14, 2006 to February 15, 2007, and then they were followed for a period of 3 months. The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional or ethical review board of at least one site in each participating country/region. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legal representative prior to enrolment.

Patients included in the study were inpatients and outpatients at least 18 years of age, who presented with a new or first episode of MDD, as defined by the diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition Text Revision,Citation26 or the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10).Citation27 Additional inclusion criteria were: Clinical Global Impressions Severity of Illness (CGI-S) score ≥ 4 (moderate) at study entry;Citation28 at least 2 months free of depression symptoms prior to the onset of the present episode; and consent to participate. Patients were excluded if their current depressive episode had persisted for more than 6 continuous months; if they had a previous or current diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or dementia; if they were experiencing chronic treatment-resistant pain or pain of an inflammatory origin related to an identified medical condition; or were simultaneously participating in another study that included a treatment intervention and/or an investigational drug.

All treatment decisions and provision of care to study participants with MDD were based solely on each health care provider’s usual practice and was independent of participation in the study. Adverse events were reported to the corresponding health authorities as per each country’s local rules, regulations, and legislation. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki and are consistent with the International Conference on Harmonization good clinical practice guidelines.

Measures

A full description of the data collected at baseline and during the study, including demographic and clinical data, has been reported previously.Citation21,Citation29

The severity of depression was assessed at baseline and at 3 months using the CGI-S and the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17).Citation30 The HAMD-17 total score ranges from 0–52, with a higher score indicating more severe depression. Response was defined as a decrease of at least 50% in the HAMD-17 total score from baseline to endpoint. Remission was defined as a HAMD-17 total score of ≤7 at the study endpoint.

Patients were assessed at baseline for either the presence or absence of PPS (PPS+ and PPS−, respectively). PPS+ was defined as a mean score of ≥2 for the seven pain-related items of the Somatic Symptom Inventory (SSI), which included abdominal pain, lower back pain, joint pain, neck pain, pain in heart or chest, headaches, and muscular soreness.Citation31 Patients rated the degree to which each symptom bothered them over the past week on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great deal).

Patient perception of QoL was assessed using the EuroQoL Questionnaire-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D).Citation32 This instrument has five items (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression), each of which is scored on a scale from 1 (no problems) to 3 (extreme problems). The responses are converted to a “utility” score that ranges from 0–1, where 0 represents deceased and 1 represents perfect health. The UK tariff was applied to the EQ-5D data of the Asian patients to calculate the utility score.Citation33 The EQ-5D questionnaire also includes a visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS), on which patients are asked to rate their current overall health that day on a scale from 0 (worst imaginable health state) to 100 (best imaginable health state), thus providing an overall “health state” score.

Data involving treatment patterns, including antidepressants and other prescribed medications and treatments for MDD and pain, were collected at baseline and during the study period, as reported previously.Citation21,Citation29

Statistical analysis

Data are summarized descriptively, with means and standard deviations (SD) for numerical variables and percentages for categorical variables.

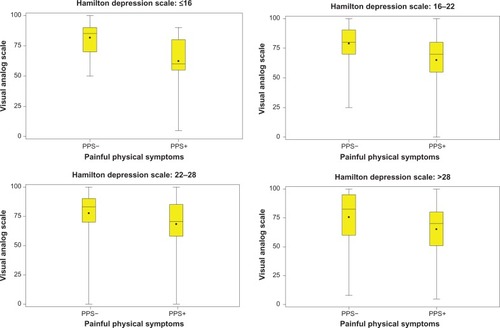

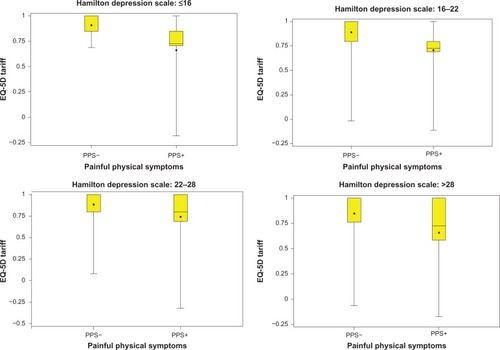

The distribution of QoL scores (EQ-5D and EQ-VAS) at the study endpoint was identified by the presence or absence of PPS at baseline, and four different levels of baseline depression severity were described using box and whisker plots. The HAMD-17 total scores used for the different depression severity levels at baseline were: ≤16, 16–22, 22–28, and >28.

Bivariate analysis examined the association between baseline variables and QoL outcomes (EQ-5D and EQ-VAS) at the study endpoint. The association between severity of depression at baseline (CGI-S, HAMD-17) and QoL at both baseline and endpoint (EQ-5D, EQ-VAS) was described using Pearson correlation coefficients.

Multivariable linear regression modeling was used to identify baseline variables (including the presence of PPS) associated with QoL outcomes at 3 months. Dependent variables were the EQ-5D score or EQ-VAS, and the independent variables were the patient demographics (age, sex, marital status, and employment status) and baseline clinical characteristics (depressive symptoms, overall severity, and QoL). Data are presented as parameter estimates and 95% confidence intervals, with P-values.

All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS statistical package version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The mean age of the total study sample of 909 patients was 45.2 years (SD 14.2) and 69% were females. Of these patients, 68.5% were married or had a de facto spouse, while 16.3% were single, and the remaining 15.2% were divorced, widowed, or separated. At baseline, 37.5% of the patients were unemployed, 35.3% were working full-time, and the remaining 14.6%, 7.2%, and 5.4%, respectively, were retired, part-time workers, and students.

Of the 909 patients in the total sample, 471 (51.8%) had PPS at baseline (PPS+). For the total sample, the baseline mean HAMD-17 total score was 23.7 (SD 5.8) and the baseline mean CGI-S score was 4.7 (SD 0.8), indicating moderate to severe baseline depression symptoms.

Bivariate analysis showed significant correlations between baseline severity of depression (HAMD-17, CGI-S) and QoL (EQ-5D and EQ-VAS) at baseline and at 3 months ().

Table 1 Bivariate correlations between depression severity (HAMD-17, CGI-S) at baseline and quality of life (EQ-5D, EQ-VAS) at baseline and at the study endpoint

Impact of pain on quality of life

The mean EQ-VAS score improved from 47.7 (SD 20.6) at baseline (n = 907) to 72.5 (SD 20.4) at endpoint (n = 715), and the mean EQ-5D score improved from 0.48 (SD 0.34) at baseline (n = 907) to 0.80 (0.26) at endpoint (n = 716).

and show that QoL (EQ-VAS and EQ-5D score) at the study endpoint differed between patients with and without PPS at baseline (PPS+, PPS−), irrespective of the baseline severity of depression based on different HAMD-17 total scores. At all depression severity levels, PPS+ patients had lower QoL scores than PPS− patients.

Figure 1 Influence of baseline PPS on endpoint EQ-VAS is consistent at different severity levels of the HAMD-17 score at baseline.

Figure 2 Influence of baseline PPS on endpoint EQ-5D score is consistent at different severity levels of the HAMD-17 score at baseline.

Bivariate analysis showed that the presence of PPS (PPS+) at baseline was a significant predictor of worse patient-rated QoL at 3 months; PPS+ patients had a mean EQ-VAS score of 66.4 (SD 21.2) versus 78.5 (SD 17.6) for PPS− (P < 0.001). Likewise, the EQ-5D scores at 3 months were 0.71 (SD 0.29) versus 0.89 (SD 0.18), for the PPS+ and PPS− groups, respectively (P < 0.001).

summarizes the results of the linear regression models and shows that the presence of PPS at baseline was a significant predictor of QoL at 3 months after adjusting for sociodemographic variables, baseline QoL, and baseline depression severity; PPS+ patients had an EQ-5D score at 3 months that was 0.12 points lower than that of PPS− patients, and an EQ-VAS score that was 9.5 points lower than PPS− patients.

Table 2 Baseline variables associated with quality of life scores (EQ-5D and EQ-VAS) at 3 months (linear regression analysis)

Discussion

This study of Asian patients treated for an episode of major depression shows that the presence of PPS negatively influences patient QoL even when the severity of depression is taken into account. Specifically, we found that patients with pain symptoms (PPS+) had a lower QoL at baseline and less improvement in their QoL after 3 months of treatment, whether measured by EQ-VAS or EQ-5D score, and when compared with MDD patients without pain symptoms (PPS−). Moreover, after adjusting for baseline covariates (including depression severity), PPS+ was a predictor of QoL at 3 months. Our findings suggest that pain has a greater impact on QoL in patients with MDD than the impact of the severity of depression.

Patients with MDD have a diminished QoL compared with healthy controls, even when in remission.Citation17,Citation18 The EQ-5D is a well established and widely used generic instrument for measuring health-related QoL.Citation34 The mean EQ-5D utility score at baseline in our sample of patients with an acute episode of MDD (0.48) was similar to that reported in previous studies of depressed patients.Citation14 Likewise, the improvement in EQ-5D seen after 3 months of treatment has also been observed in other studies of patients treated with antidepressants.Citation14,Citation17,Citation35

The most important finding of our study is that the presence of PPS at baseline has a substantial impact on patient QoL after 3 months of treatment. After adjusting for covariates, the differences in EQ-5D and EQ-VAS scores at 3 months between patients with and without PPS (0.12 and 9.5 points, respectively) can be considered to be clinically relevant, as they are above the threshold for an important difference reported by some researchers (0.05 or 0.07 for the EQ-5D utility score).Citation35,Citation36

Our results are consistent with the findings from previous studies showing that it is the intensity and extent of pain symptoms at baseline that contribute significantly to a less favorable response to depression medication, and to the need for a longer duration of treatment to obtain a satisfying result, if at all.Citation7,Citation9,Citation37 QoL is an important measure of treatment success in depression.Citation18 Previous studies have shown that QoL is decreased in patients with depression and somatic symptoms,Citation38 and that greater severity of pain is associated with worse depression, a lower QoL, and a poorer treatment response.Citation7,Citation8 The European FINDER study revealed that having fewer somatic symptoms at baseline was associated with better QoL outcomes, whereas more severe pain at baseline (higher pain VAS) was associated with a worse EQ-5D score at 6 months.Citation19

The impact of depression severity on QoL in depressed patients with somatic symptoms has not been reported previously, but a few studies have examined the influence of depression severity on QoL. Primary care patients with MDD had significantly lower EQ-5D scores at baseline and during treatment in patients with increasing disease severity, as measured using the CGI-S.Citation35 This French study also showed that QoL at 8 weeks’ follow-up differed according to patient response to treatment, with responders having a higher EQ-5D score at the study endpoint than nonresponders (0.85 versus 0.58, respectively).Citation35 Among elderly patients with recurrent MDD, an improvement in depression symptoms after 6 weeks of treatment correlated with an improvement in QoL (as measured using the Short Form-36 Health Survey Questionnaire, SF-36), especially in patients who achieved full remission compared with partial responders and nonresponders.Citation38 A study of 103 MDD patients in China reported that increasing severity of depression (higher HAMD total score) was significantly associated with a worse QoL at baseline (SF-36).Citation39 Also, after 6 weeks of antidepressant treatment, less improvement in QoL was significantly associated with a higher HAMD score at baseline.Citation39 However, another study reported few differences in QoL (as measured by SF-36 scores) between patients with different levels of depression severity (based on ICD-10 classifications).Citation40

The present results from this large-scale observational study in Asian patients with MDD extend upon the findings that have been reported previously. Lee et alCitation21 showed that PPS+ patients (51.8% of the total sample) were more significantly depressed and had a lower QoL than PPS− patients. Moreover, the PPS+ patients have less improvement than the PPS− patients on depression, pain, and QoL measures during 3 months of treatment.Citation29 Consistent with our results, a recent study of 414 Korean outpatients with MDD found that 30.4% had PPS present, and that this PPS+ group had significantly greater depression severity and a lower QoL (EQ-VAS) than the group without PPS.Citation41 Thus, there is growing evidence that emphasizes the importance of assessing PPS in patients with depression so that treatments can be targeted to improve outcomes, including patient QoL. Scales commonly used in depression, such as the HAMD-17, have few pain items and, therefore, may underestimate the effect of pain symptoms on both depression and QoL.Citation42

Pain and depression have complex pathophysiological mechanisms that are similar, but not yet fully understood.Citation20,Citation22–Citation25 The neurochemicals serotonin and norepinephrine are involved in both phenomena, showing that pain and depression are interrelated.Citation43 Studies have shown that brain regions involved in the generation of emotion (eg, the medial prefrontal cortex, insular and anterior prefrontal cortex, hypothalamus, and amygdala), send many projections to brainstem structures involved in pain modulation, such as the periaqueductal gray and the rostral–ventromedial medulla.Citation20 Despite an overlap in the underlying neurobiological processes of pain and depression, there must be differences because they both contribute to patient QoL.

The clinical implications of this study may be that in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with depression, we should pay close attention to pain symptoms. Epidemiologic studies have found that about 50% of patients with depression who consult primary care doctors are not appropriately diagnosed. The main reason for the lack of detection of many patients is the reason for consultation. When patients present simultaneously with mood and pain symptoms, they frequently usually complain of the pain symptoms, and the physician may overlook the presence of mood symptoms in these patients.Citation20

Besides, when selecting treatment for patients with depression, physicians must determine whether somatic symptoms (especially pain) are present, and they must use treatments that target both the emotional and physical symptoms of depression; this approach should lead to better depression and QoL outcomes for depressed patients who present with PPS.Citation43

Some limitations of the present study should be considered when interpreting the results. First, given the observational design of the study, our findings should be interpreted conservatively. Second, somatic symptoms were collected using a specific questionnaire (Somatic Symptom Inventory); however, we do not know how many of the somatic symptoms the patients would have reported of their own accord if not prompted by the questionnaire. Third, patients from primary care were not included in this study; only patients from psychiatric care settings were included. Therefore, our sample is not representative of the total MDD population in these Asian countries and limits the generalizability of our findings to primary care patients with major depression. Fourth, comorbidity with anxiety disorders was not assessed, and could be a factor contributing to patient QoL. Fifth, the analyses were based on depression severity and it is unknown whether the same findings would be observed if pain severity had also been taken into account. Additional limitations are that the analysis did not take into account the antidepressant prescribed, which may influence patient QoL ratings at 3 months. Also, we did not assess use of pain relief medication. Finally, because there is no Asian EQ-5D questionnaire, we applied the commonly-used UK version to the EQ-5D data of the Asian patients to calculate the utility scores.Citation33 However, there is evidence that different populations value health states differently, including racial/ethnic differences.Citation44–Citation46 Nevertheless, the EQ-5D has been shown to be useful for assessing QoL in patients with MDD,Citation35 and to have acceptable validity and reliability in Asian populations.Citation47 In addition, both the EQ-VAS and the EQ-5D utility scores have been shown to be responsive to change in patients with depression.Citation48,Citation49

Despite these potential limitations, the results of our study indicate that the presence of PPS is associated with a lower QoL in patients receiving treatment for major depression, and this is not dependent on the severity of depressive symptoms. Our findings imply that clinicians need to take into account the presence of pain symptoms when diagnosing a patient with major depression and when deciding on a treatment strategy for such patients.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. Diego Novick, William Montgomery, Zbigniew Kadziola, and Xiaomei Peng are employees of Eli Lilly and Company. Jaume Aguado has conducted the statistical analysis under a contract of Fundació Sant Joan de Déu with Eli Lilly and Company. Roberto Brugnoli has acted as a consultant, received grants, and acted as a speaker in activities sponsored by the following companies: BMS, Eli Lilly, and Innovapharma, Sigma-Tau. Josep Maria Haro has acted as consultant or speaker for Astra-Zeneca, Eli Lilly and Company, Lundbeck, and Roche.

References

- World Health OrganizationThe Global Burden of Disease: 2004 UpdateGenevaWorld Health Organization2008

- BrometEAndradeLHHwangICross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episodeBMC Med201199021791035

- NovickDMontgomeryWAguadoJKadziolaZPengXBrugnoliRHaroJMWhich somatic symptoms are associated with an unfavorable course in Asian patients with major depressive disorder?J Affect Disord Epub 2013 Mar 19.

- KirmayerLJRobbinsJMDworkindMYaffeMJSomatization and the recognition of depression and anxiety in primary careAm J Psychiatry199315057347418480818

- LeeMin SooYumSun YoungHongJin PyoAssociation between Painful Physical Symptoms and Clinical Outcomes in Korean Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: A Three-Month Observational StudyPsychiatry Investig200964255263

- CorrubleEGuelfiJDPain complaints in depressed inpatientsPsychopathology200033630730911060514

- BairMJRobinsonRLEckertGJStangPECroghanTWKroenkeKImpact of pain on depression treatment response in primary carePsychosom Med2004661172214747633

- MuñozRAMcBrideMEBrnabicAJMajor depressive disorder in Latin America: the relationship between depression severity, painful somatic symptoms, and quality of lifeJ Affect Disord2005861939815820276

- KarpJFScottJHouckPReynoldsCF3rdKupferDJFrankEPain predicts longer time to remission during treatment of recurrent depressionJ Clin Psychiatry200566559159715889945

- PaykelESRamanaRCooperZHayhurstHKerrJBarockaAResidual symptoms after partial remission: an important outcome in depressionPsychol Med1995256117111808637947

- BurtVKPlotting the course to remission: the search for better outcomes in the treatment of depressionJ Clin Psychiatry200465Suppl 12202515315474

- GrecoTEckertGKroenkeKThe outcome of physical symptoms with treatment of depressionJ Gen Intern Med200419881381815242465

- PaykelESScottJTeasdaleJDPrevention of relapse in residual depression by cognitive therapy: a controlled trialArch Gen Psychiatry199956982983512884889

- HaysRDWellsKBSherbourneCDRogersWSpritzerKFunctioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnessesArch Gen Psychiatry199552111197811158

- WellsKBStewartAHaysRDThe functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the Medical Outcomes StudyJAMA198926279149192754791

- SobockiPEkmanMAgrenHHealth-related quality of life measured with EQ-5D in patients treated for depression in primary careValue Health200710215316017391424

- ten DoesschateMCKoeterMWBocktingCLScheneAHfor DELTA Study GroupHealth related quality of life in recurrent depression: a comparison with a general population sampleJ Affect Disord20101201–312613219446342

- IsHakWWGreenbergJMBalayanKQuality of life: the ultimate outcome measure of interventions in major depressive disorderHarv Rev Psychiatry201119522923921916825

- ReedCMonzBUPerahiaDGQuality of life outcomes among patients with depression after 6 months of starting treatment: results from FINDERJ Affect Disord2009113329630218603303

- BairMJRobinsonRLKatonWKroenkeWDepression and pain comorbidity: a literature reviewArch Intern Med2003163202433244514609780

- LeePZhangMHongJPFrequency of painful physical symptoms with major depressive disorder in Asia: relationship with disease severity and quality of lifeJ Clin Psychiatry2009701839119192462

- BasbaumAIFieldsHLEndogenous pain control mechanisms: review and hypothesisAnn Neurol197845451462216303

- WilliamsLJJackaFNPascoeJADoddSBerkMDepression and pain: an overviewActa Neuropsychiatr20061827987

- KapfhammerHPSomatic symptoms in depressionDialogues Clin Neurosci20068222723916889108

- StahlSMThe psychopharmacology of painful physical symptoms in depressionJ Clin Psychiatry200263538238312019660

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Text Revision: DSM-IV-TR4th edWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association2000

- World Health OrganizationInternational Classification of Diseases and Related World Health ProblemsGenevaWorld Health Organization2007

- GuyWECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, RevisedBethesda, MDUS Department of Health, Education, and Welfare1976

- AngQQWingYKHeYAssociation between painful physical symptoms and clinical outcomes in East Asian patients with major depressive disorder: a 3-month prospective observational studyInt J Clin Pract20096371041104919570122

- HamiltonMA rating scale for depressionJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry196023566214399272

- KroenkeKSpitzerRLWilliamsJBPhysical symptoms in primary care. Predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairmentArch Fam Med1994397747797987511

- EuroQoL – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of lifeHealth Policy199016319920810109801

- BrooksRRabinRde CharroFThe Measurement and Valuation of Health Status Using EQ-5D: A European PerspectiveDordrecht, The NetherlandsKluwer Academic Publishers2003

- RabinRde CharroFEQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol GroupAnn Med200133533734311491192

- SapinCFantinoBNowickiMLKindPUsefulness of EQ-5D in assessing health status in primary care patients with major depressive disorderHealth Qual Life Outcomes200422015128456

- WaltersSJBrazierJEComparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6DQual Life Res20051461523153216110932

- SimonGEvon KorffMLinEClinical and functional outcomes of depression treatment in patients with and without chronic medical illnessPsychol Med200535227127915841684

- DoraiswamyPMKhanZMDonahueRMRichardNEQuality of life in geriatric depression: a comparison of remitters, partial responders, and nonrespondersAm J Geriatr Psychiatry20019442342811739069

- CaoYLiWShenJZhangYAssociation between health related quality of life and severity of depression in patients with major depressive disorderZhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban2011362143148 Chinese.21368424

- NuevoRLeightonCDunnGImpact of severity and type of depression on quality of life in cases identified in the communityPsychol Med201040122069207720146833

- BahkWMParkSJonDIYoonBHMinKJHongJPRelationship between painful physical symptoms and severity of depressive symptomatology and suicidalityPsychiatry Res2011189335736721329990

- HungCIWengLJSuYJLiuCYDepression and somatic symptoms scale: a new scale with both depression and somatic symptoms emphasizedPsychiatry Clin Neurosci200660670070817109704

- TrivediMHThe link between depression and physical symptomsPrim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry20046Suppl 1121616001092

- JohnsonJALuoNShawJWKindPCoonsSJValuations of EQ-5D health states: are the United States and United Kingdom different?Med Care200543322122815725978

- FuAZKattanMWRacial and ethnic differences in preference-based health status measureCurr Med Res Opin200622122439244817257458

- NormanRCroninPVineyRKingMStreetDRatcliffeJInternational comparisons in valuing EQ-5D health states: a review and analysisValue Health20091281194120019695009

- WangHMPatrickDLEdwardsTCSkalickyAMZengHYGuWWValidation of the EQ-5D in a general population sample in urban ChinaQual Life Res201221115516021505881

- GüntherOHRoickCAngermeyerMCKönigHHThe responsiveness of EQ-5D utility scores in patients with depression: A comparison with instruments measuring quality of life, psychopathology and social functioningJ Affect Disord20081051–3819117532051

- GerhardsSAHuibersMJTheunissenKAde GraafLEWiddershovenGAEversSMThe responsiveness of quality of life utilities to change in depression: a comparison of instruments (SF-6D, EQ-5D, and DFD)Value Health201114573273921839412