Abstract

Aim

To explore and analyze perceptions of service users and caregivers on adherence and nonadherence to medication in a mental health care context.

Background

Mental health medication adherence is considered problematic and legal coercion exists in many countries.

Design

This was a qualitative study aiming to explore perceptions of medication adherence from the perspective of the service user (and their caregiver, where possible).

Participants

Eighteen mental health service users (and six caregivers) with histories of medication nonadherence and repeated compulsory admission were recruited from voluntary sector support groups in England.

Methods

Data were collected between 2008 and 2010. Using qualitative coding techniques, the study analyzed interview and focus group data from service users, previously subjected to compulsory medication under mental health law, or their caregivers.

Results

The process of medication adherence or nonadherence is encapsulated in an explanatory narrative. This narrative constitutes participants’ struggle to negotiate acceptable and effective routes through variable quality of care. Results indicated that service users and caregivers eventually accepted the reality of their own mental illness and their need for safety and treatment. They perceived the behavior of professionals as key in their recovery process. Professionals could be enabling or disabling with regard to adherence to medication.

Conclusion

This study investigated service user and caregiver perceptions of medication adherence and compulsory treatment. Participants described a process perceived as variable and potentially doubly faceted. The behavior of professionals was seen as crucial in collaborative decision making on medication adherence.

Introduction

Health services users who experience mental disorders or distress may in certain circumstances be medicated without their consent. Concern about a lack of adherence to recommended medication is common in many countries and legal intervention has increased across most of the western world.Citation1 However, legalized compulsory treatment in the context of mental health practice is contentious and opinion is divided regarding its therapeutic value or justifiability.Citation2

Caring for people placed on compulsory treatment orders raises questions around what types of professional behavior are considered acceptable to both mental health service users and to caregivers. There exists an inherent tension in providing care within a context of surveillance and potential restraint. This represents a significant challenge for professionals and mental health service users in cases where medication adherence is an issue. Consequently, it is necessary to examine medication adherence from the perspective of service users (and their caregivers) in cases where users were previously mandatorily medicated under mental health law. Understanding service user views can help professionals deliver care sensitively and competently in cases where medication adherence may be compromised.

This paper focuses on a study of those who have been subjected to British mental health legislation and compulsory medication after their partial or complete nonadherence to medication. Using interviews and a focus group, it explores the perceptions of 24 participant service users (and their caregivers, where possible) on medication nonadherence. This was not a comparison of service user and caregiver perspectives but instead a study focused on understanding the medication adherence process of each case.

Background

Failure to take prescribed medication is a common occurrence in many long-term conditions; it has been contentious since the time of Hippocrates some 2,000 years ago.Citation3 Although many mental health service users are prone to nonadherence, most concern around nonadherence is directed at severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia.Citation4 A review of the literature concludes that the situation has not improved over the past 30 years.Citation5

Initially, compulsory medication was confined to inpatient settings. However, as community care became the norm in the developed world, the case was made for extending the mental health act in the UK beyond the hospital setting.Citation6 Since its inception, there has been anxiety about the adequacy of community care for service users. This often focuses on whether medication regimes are maintained and the potential for dangerous behavior should service users become disordered following nonadherence.

Internationally, there is concern surrounding the costs associated with nonadherence to antipsychotic medication; these include poor outcomes for individuals and problematic financial implications due to repeated hospitalization for health services.Citation4 In Britain, a succession of mental health service user homicides occurred throughout the late 1980s and 1990s.Citation7,Citation8 Recently, other cases have attracted press attention.Citation9,Citation10 The media and public perception is that poor supervision and medication nonadherence are frequently occurring events. Despite this perception, there is little evidence to support it, with the number of attacks small and continuing to decrease.Citation11,Citation12 Nevertheless, concern remains about the various problems associated with medication adherence.

Considerable evidence exists that second generation drugs can lead to weight gain, which is linked with several health problems.Citation13,Citation14 Medication may be accepted by many as necessary in mental health conditions, yet there is still much research required to understand these associations so as to achieve the most effective prescribing and condition management.Citation15 Service users have expressed concern about weight gain and subsequent effects on lifestyle and health status.Citation16

As a result of these concerns, there have been calls for more collaborative decision making with mental health service users; this would complement the legal measures in place to increase medication adherence. A recovery framework with this inclusive approach is advocated and service user involvement prioritized.Citation17 Over the past decade, professionals have been urged to develop concordance with service users regarding medication choices.Citation18 Collaborative decision making is defined as “a process of engagement in which health professionals and patients (and their loved ones) work together […] to understand clinical issues and determine the best course of action.”Citation19

Conversely, concepts of service user involvement, collaboration, and concordance do fit easily into a mental health system that holds the power to impose compulsory medication. Mental health service users and professionals find themselves in a somewhat paradoxical position. Health professionals must perform a caring and collaborative role whilst simultaneously policing and enforcing medication adherence.

Studies clearly profile a nonadherent individual as being of an ethnic minority, male, single, and under the age of 40 years.Citation20,Citation21 Studies in the 1980s and 1990s suggested that increasing compulsion resulted in improved medication adherence.Citation22 However, research exploring service user perspectives suggests anxiety at being compulsorily medicated.Citation23 Using content analysis with thematic and domain identification, they found the majority had negative feelings about their involuntary treatment.Citation24 The experience of involuntary treatment exacerbated service users’ feelings of stigma and powerlessness.

A study on supervised discharge orders with service users produced mixed views about the order. Many believed themselves to be disempowered by such orders, while others recognized the value of reciprocal benefits such as accommodation.Citation25 In other research, the opinions of patients, their caregivers, mental health professionals, and community agency representatives were sought regarding the use of Community Treatment Orders (CTOs) in Saskatchewan, Canada.Citation26 In-depth interviews and focus groups were used to collect data from service users, caregivers, mental health professionals, and community agency representatives. Again, results indicated mental health service users had contradictory feelings about CTOs.

Where collaboration decision making with service users with bipolar affective disorder was prioritized, better adherence rates were recorded.Citation27 A total of 306 participants were randomly assigned to a collaborative care program or to conventional care; they were then monitored with a 3 year follow-up period. Compared to those assigned to conventional care, those assigned to collaborative care had a 40% improvement in medication adherence at 3 years. The authors clarify that these findings are not generalizable as participants were all army veterans. In addition, the intervention was multifaceted and the authors note more work is required to examine which aspects are important. However, this study does indicate that collaborative engagement with service users is a fruitful area that is ripe for exploration.

Medication satisfaction, particularly regarding side effects, is an important aspect of adherence. Subjective satisfaction was explored in 121 stabilized, service users, using the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM).Citation14 Participants also rated their symptoms using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).Citation14 When compared to patients prescribed first generation drugs, those taking second generation antipsychotics reported better satisfaction levels but little difference in symptom ratings. The study acknowledged methodological limitations in that it was multiply centered, with small numbers for certain drugs. Nonetheless, it adds to work in the field and reflects findings on medication satisfaction available at the time. This issue is now reflected in national guidelines on the treatment and management of schizophrenia, with second generation antipsychotics now recommended.Citation28 However, as noted earlier, these are now known to be accompanied by other health problems. Obesity, diabetes, and cardiac problems and their associated early mortality rates have become issues for mental health clients.Citation15,Citation29 The subjective experience of weight gain was explored with 18 service users in a qualitative and constructivist study.Citation16 Analysis using the constant comparative method emphasized the complexity of weight management and its deleterious effect on individual lifestyle.

There is now debate over whether increased legal coercion ensures improved outcomes.Citation21,Citation30 Epidemiological research utilized a survival analysis on 265 CTO cases with matched controls and 224 consecutive controls.Citation20 Patients were studied over a 12 month period to monitor readmission rates and occurrence of any forensic episodes. The CTO group had a significantly higher readmission rate, with 72% of subjects readmitted in comparison to 59% and 52% for the respective control groups. In addition, a pilot study of CTOs and hospital utilization rates in Australia found that their effect was limited.Citation31

It is claimed that it is difficult to carry out well controlled, methodologically sound quantitative research in this area because subjects may be psychologically distressed.Citation30 Although a number of nonexperimental studies have been carried out in Australasia, Canada, and the United States, “it is problematic to generalize from findings because of variations in methodologies, legal frameworks, and the contexts.”Citation32

Mixed results therefore emanate from the empirical evidence available about the outcomes of legally enforced adherence measures, with later studies suggesting less evidence of efficacy. Existing qualitative research suggests that the experience of coercion is complex and requires further exploration. Service users generally find coercion distressing, yet there is limited evidence of effectiveness in improving outcomes. There is concern at the ethical implications of using even more coercive measures, given the existing evidence.Citation33,Citation34 It is crucial to understand more about the subjective impact on those likely to be subjected to the effects of compulsory powers.Citation32

Aims and objectives

Aims and objectives were deliberately open in accordance with qualitative coding techniques based on grounded theory.Citation35 This research aimed to explore and analyze perceptions of service users and caregivers on adherence and nonadherence to medication, in the mental health care setting. Prior to data collection, an advisory group of six individuals with a history of nonadherence and compulsory admission gave advice regarding the types of questions to ask.

The research objectives were to understand the following: (1) service user and caregiver perceptions of care when adherent to medication; (2) service user and caregiver perception of care when nonadherent to medication; (3) how service users and caregivers characterize the process of adherence and nonadherence; (4) how service users and caregivers perceive the process of detention and compulsory medication within mental health services; and (5) service users’ and caregivers’ views and opinions on whether, and how, they could be helped to adhere to medication.

Design

The initial phase of the research analyzed interview data, either individually or in pairs, the latter when the service user wished to include their caregiver. The second phase reviewed emerging findings with participants either individually or in a focus group. It was important that findings in a study on service user perspectives were recognizable to participants.Citation36 Data generation and analysis were conducted using qualitative coding based on grounded theory techniques. There is much debate about the grounded theory method originally developed in the 1960s. Many agree that adaptations to the classic method are acceptable, and even desirable, provided systematization and transparency are maintained.Citation35,Citation37,Citation38 This study used analytic techniques as recommended by Strauss and Corbin.Citation39 However, it does not adhere to the classic grounded theory of “literally ignoring the literature.” It is conducted in line with acknowledgment that the existing theoretical and experiential perspectives of researchers will influence findings socially constructed together with participants.Citation41

Participants

Sampling was initially purposeful and inclusion criteria called for adults with a history of legal compulsion to take medication due to partial or nonadherence to mental health medication (at least two compulsory admissions). Exclusion criteria were those who might be actively distressed and/or on compulsory treatment orders at that time. It was important that the study interviewed people who had time to reflect upon the process of medication adherence. Participants were recruited through local voluntary sector support groups so potential participants could feel reassured about speaking freely and with no direct connection to their treatment team.

Following presentation of the research project, participants volunteered. Only those who had previously been sectioned under mental health law on more than one occasion were selected. A number of people volunteered, despite never having been legally detained and medicated. These people explained that they had nonetheless felt coerced into taking medication. This was an interesting development and, as is noted, fits with literature on mental health service user perspectives, but unfortunately it did not fit the inclusion criteria for this study.Citation2

Although statistical representation is not the objective of qualitative research it is necessary to have some form of portrayal of the cultural group most likely to be subject to compulsory medication (as the literature demonstrates).Citation42 Therefore it was also important to ensure young black men were represented.Citation21 This was achieved (see ).

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of participants

Data generation

Initial purposeful and then theoretical sampling guided the ongoing iterative process of selecting participants for data generation. The period of data collection was 2008–2010. Data were generated through individual interviews and a focus group with 24 participants in a large English city. Originally, study design intended to focus on interview data alone; however, the design was modified in response to participant request and a focus group convened for member checking purposes.

Participants were recruited through local voluntary sector support groups. In accordance to participant preference interviews were conducted at the support group’s premises, the interviewee’s home, or a convenient local hospital.

Data were collected by IG and analyzed with AG and MC. Individual (or joint, consisting of one or more caregivers, according to service user preference) interviews were carried out with 14 service users and six caregivers. This was not a comparison of service user and caregiver perspectives but instead focused on understanding the medication adherence process in each case. The iterative process of grounded theory suggested certain areas for further exploration (one minority ethnic group family and another white English grouping). In the final respondent validation phase, in order to consider, influence, and validate emerging findings, one service user and caregiver pairing were reinterviewed, another service user was reinterviewed alongside three new caregivers nominated by him, and a focus group convened. This group constituted three service users already individually interviewed and four new participants with a similar history of nonadherence with mental health medication.

Interviews were largely unstructured, in line with the grounded theory approach. Consequently, as indicated above, areas for exploration were initially identified but the interview process followed advice to pursue information provided by participants as opposed to adhering to rigid formats.Citation37 The interviews were sound recorded and transcribed.

Data analysis

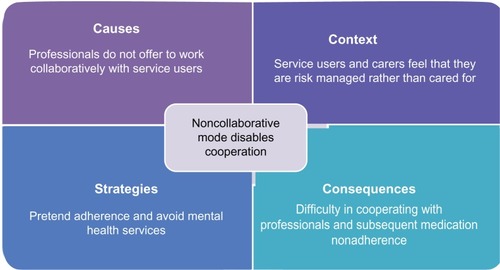

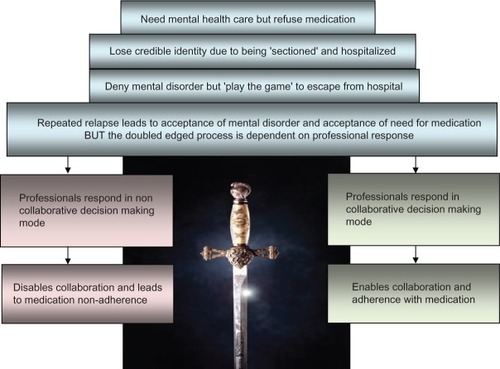

Data were analyzed using the constant comparative method. Open, axial, and selective coding took place in line with advice from Strauss and Corbin,Citation39 Charmaz,Citation37 and Dey.Citation38 Line by line scrutiny took place using MAXQDA to generate multiple open codes. The software breaks down the text into hundreds of open codes. These are generally ascribed titles reflecting the in vivo data. After generating a large number of open codes, axial coding selected those that seemed to best connect and to be most promising for further elaboration. These became categories and were further refined using the coding paradigm, as illustrated by –. Categories also are described in terms of their properties and dimensions (descriptions and degrees). Therefore categories emerged and developed from open coding by connecting similar open codes, redefining these, and subjecting them to examination in terms of causation, context, consequences, and strategies employed. Data generation and analysis were iterative however, and there were two main phases. Initially, interview data were gathered and analyzed. Emergent findings were presented to service users and caregivers and to a focus group for respondent validation. Data from this phase were then submitted to form final analysis.

Validity and reliability

Credibility and trustworthiness are necessary in terms of transparency of process in qualitative research.Citation36 The use of grounded theory coding techniques combined with the MAXQDA software package enables visibility of data generation and analytic procedures.

IG is a nursing lecturer but previously worked as a community psychiatric nurse and was involved in monitoring medication adherence. However, participants were not previously known to any of the authors. The researchers believed that despite occupational history of medication monitoring and adherence encouragement, they were open to possible alternative service user perspectives. A number of measures to reduce the possibility of existing views overly influencing findings were taken. As described above, respondent validation with participants was carried out to allow participants to consider, challenge, influence, and validate the authenticity of findings.Citation43 Their input had considerable impact on the weighting put on certain aspects of final analysis of findings, as will be highlighted later in this paper. Additionally, as noted above, codes were further subjected to examination with AG and MC. It is also argued that inclusion of caregivers’ views aids triangulation, in adding source diversity to the data.Citation36

Ethical review

The project proposal was submitted to the United Kingdom National Research Ethics Service and ethical approval was obtained from the local ethics committee. Adaptation of study design to include a focus group was also approved at a later stage by the local ethics committee. Participants were provided with information sheets explaining the rationale, risks, and potential benefits of taking part in the research. Participants were assured that they could decline or cease participation at any point, with no adverse consequences. Information regarding the standards of confidentiality and anonymity in any published findings was also explained. Arrangements were made to ensure that support would be available should they become distressed.

Results

Data were transcribed and examined line by line to produce multiple open codes.

Developing the story through axial coding

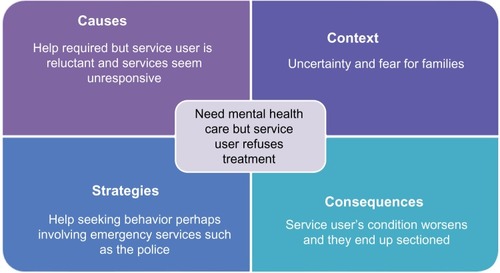

After data were open coded, they were grouped and further subsumed under more conceptual and inclusive axial codes to form categories. Category building raises theory to more abstract and conceptual levels.Citation37,Citation38,Citation41 Processes around medication and use of compulsory powers were selected as categories and subjected to scrutiny regarding causal, contextual factors, strategies employed, and resultant consequences using the coding paradigm, as recommended by Strauss and Corbin (see ).Citation39 The following string of linked categories provides the narrative of the pathway through mental health services for participants in this research.

There are two potential care pathways in a double-edged process of mental health medication adherence (see ). It commences with the category “need mental health care but service user refuses treatment”, with participants describing:

The times my husband and I begged them to come out and have a look at her so I told them and I didn’t pull any punches, they didn’t listen to us. (Caregiver D: 95-year-old Caucasian)

I had him at home for 7 months talking gibberish at the T V, no help.

(Caregiver C: 43-year-old Caucasian)

I can’t tell when I’m going wrong but my Mum can see it.

(Service user S: 28-year-old African-Caribbean male)

I’d be sitting here on the stair all night, I’d phone the doctor in the morning and say he’s not well, they say “Is he harming anyone? Is he a harm to himself?” I ’d say no, then the doctor would say to me that they can’t do anything until he hurts somebody or hurts himself. I had to phone the Samaritans in the middle of the night sometimes they told me I’d have to wait until he did something; that was my greatest fear, that he’d do something to someone. (Caregiver S: 89-year-old African-Caribbean female)

Open codes relating to this part of the process are as follows: (1) compulsory powers can be necessary; (2) the only way to get help; (3) unresponsive services; (4) crisis management involving emergency services.

Caregivers reported a distressing experience of needing help but having difficulty accessing care (see ). The service user would not accept voluntary care and mental health services seemed unresponsive. Their strategy was to gain access to treatment through the emergency route, and service users were sectioned using mental health legislation (‘sectioned’ is the common term used to describe being placed under a section of the mental health act in the UK).

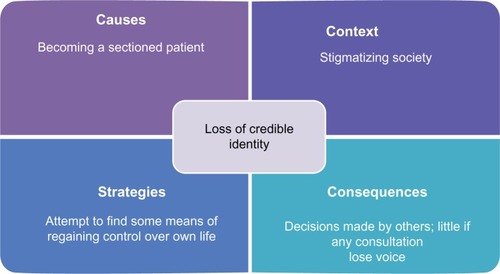

At this stage, service users found themselves “losing a credible identity” (due to being sectioned), claiming:

They make all these decisions based on I don’t know what, because they don’t listen to me well when I’ve been sectioned and I felt like my rights had been taken away from me. (Service user N: 45-year-old Caucasian female)

They talk about me behind my back, then they tell me what the team decided. (Service user C: 23-year-old Caucasian male)

I used to be someone, went to college, had a job, now I’m just a patient. (Service user P: 26-year-old African-Caribbean male)

I’m just another black woman with schizophrenia.

(Service user K: 34-year-old African-Caribbean female)

Open codes relating to this category are as follows: (1) stigmatized; (2) just a patient; (3) she used to work; (4) not worth being listened to; (5) defined by mental illness.

Becoming a sectioned patient within the context of a society that stigmatizes mental disorder results in the consequence of a loss of voice (see ). The identity of a sectioned patient is a discredited identity. Service users in this study sought means of regaining control.

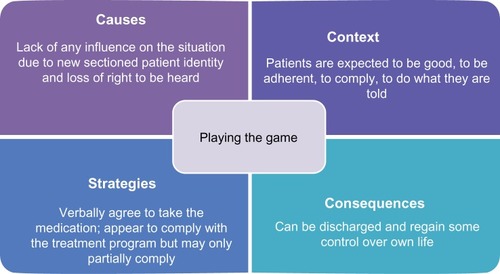

At this stage, service users still deny their mental disorder but recognize that professionals reward compliant behavior. In order to cope and regain some control they resort to the category of “playing the game” (appearing to be a compliant patient), explaining:

Well I take it [medication] because I feel it helps to keep me on an even keel and I do feel it is helpful to keep me on an even keel but I do think, I may miss a day or miss two days and I don’t always take it every single day but for them [professionals], they think it’s compliance and you must take the medication every single day. (Service user K: 34-year-old African-Caribbean female)

This next participant initially seemed to be a potential deviant case, claiming that she had not had any disagreement with professionals regarding medication issues. However, she had been detained and medicated without consent. On further exploration, she explained that she had strategies for avoiding confrontation, noting:

I’m good at being compliant, my friend got into trouble but I didn’t argue. (Service user Q: 32-year-old African-Caribbean female)

She observed that appearing to behave in a certain manner yielded results. She managed to get herself discharged as soon as possible by mimicking demeanor she believed the professionals perceived as ‘well’. She noted:

I manipulated my way out of the section I didn’t talk about the things that were hounding me, I sort of avoided subjects that were extreme. (Service user Q: 32-year-old African-Caribbean female)

Others explained how they manipulated dosages to allow them to cope with their lives while still appearing adherent.

I can’t take the full dose with two young children to bring up but you can’t tell them. (Service user B: 43-year-old African-Caribbean female)

Open codes relating to this category are as follows: (1) hospitalization is unpleasant; (2) feeling physically unwell as a result of medication; (3) try to take back some control; (4) appearing adherent; (5) complexity/partiality of adherence.

Service users described feeling powerless but recognizing that medication adherence was expected of them (see ). They described how medication could be difficult to tolerate, leaving them feeling physically unwell and overly sedated. They felt that professionals often did not fully appreciate this, and they therefore hid their partial adherence from professionals. Nonetheless, the appearance of being compliant enabled discharge as a consequence.

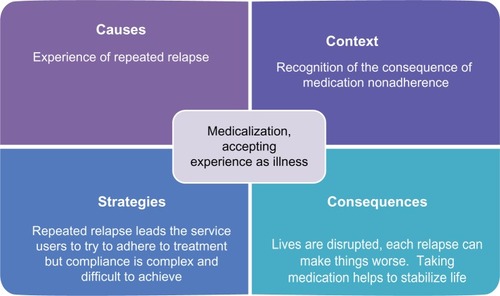

However, over time and with repeated relapse, service users reluctantly accept their experience as illness requiring treatment including medication. This resulted in the category “accepting mental disorder”, with participants explaining:

It could have been a one-off, I wouldn’t have believed I needed the medication after the first admission but now I know and I know that each relapse makes it worse. (Service user O: 38-year-old Caucasian male)

Now she knows she’s ill now and she takes her medication and she knows she has to and it actually helped her. (Caregiver D: 95-year-old Caucasian female)

I know now that I’m ill, I’ve proved it to myself now, I was in the hostel for about a year I reduced the medication with the knowledge of the people around me and after a year. They said “let’s see what happens”. After about 3 months I relapsed. (Service user S: 26-year-old African-Caribbean male)

The open codes for the category of accepting mental disorder are as follows: (1) initial denial; (2) acknowledging reality of mental illness; (3) reluctant acceptance of need for medication; (4) proved it to myself.

Having accepted their mental disorder as a reality, service users recognized they needed to take medication. An acceptable medication regime helps to prevent relapse and stabilize life (see ).

However service users found the process of obtaining effective treatment complex and adherence difficult to achieve. They described their perception of encountering two potential reactions in professionals, “collaborative decision-making mode” or “noncollaborative mode.”

Regarding how collaborative decision making enables cooperation, they reported:

I think my CPN [Community Psychiatric Nurse] takes on board what I say she’s quite good, I can like test the waters with her and then we will think about it and not just on one single answer but look for a variety of avenues to follow. Weight gain is an issue with some of the medication. (Service user N: 34-year-old African-Caribbean female)

Well they tried to help me they tried to change my medication, they tried to change it to one that didn’t give me weight gain, tried to be, at times, supportive of me when I had mental health problems and issues. (Service user Y: 36-year-old African-Caribbean female)

There was one Chinese doctor, she listened and she got me on the right medication. (Service user D: 52-year-old Caucasian female)

Open codes for this category are as follows: (1) good professional care is appreciated; (2) treating service users and caregivers with respect; (3) partnerships with patients; (4) adherence is possible but requires enabling; (5) good professional care enables adherence.

Collaborative decision making enabling cooperation results in medication adherence (see ). Where professionals listened and invited collaboration in decision making, they were perceived as more likely to understand the issues and offer acceptable medication regimes. Service users and caregivers in this study described being able to trust these professionals to hear their concerns. They wished to maintain contact and they felt they could adhere with medication where they had been involved in the process. However, the process can be double edged and service users and caregiver participants also described meeting professionals in the opposite category. In the respondent validation phase, participants challenged emerging findings, stressing the need to highlight the less collaborative elements of care, “noncollaborative mode disables cooperation”; they described their experience as follows:

I had to sort out the side effects myself, I said but they didn’t do anything. (Service user Q: 32-year-old African-Caribbean female in focus group)

My psychiatrist at present says, you know, the nurses aren’t there to speak to you, I thought that’s not very good. (Service user G: 45-year-old Caucasian female)

They treated us like the opposition. (Caregiver D: 95-year-old Caucasian female)

Seeing only the illness, not the person. (Service user O: 24-year-old African-Caribbean male in focus group)

They just risk manage and give medication. (Service user W: 55-year-old African-Caribbean male in focus group)

I could just pretend to take the medication, people could go underground. (Service user O: 33-year-old Caucasian male)

The open codes for this category are as follows: (1) lack of necessary information; (2) side effects not managed; (3) took years to get the right medication; (4) over medicated; (5) treated like a nuisance/problem, not a patient.

Participants described professionals who would not listen, would not address their side effects and did not offer to work in collaboration (see ). They described the difficulties in reaching a situation where tolerable and helpful medication regimes could be attained. Medication adherence was described as compromised when professionals seemed reluctant to listen to their genuine concerns. The possibility of cooperating with treatment was perceived as unlikely in these situations.

The story therefore involves initial resistance to intervention, followed by eventual acceptance of a mental health disorder, but only after experiencing repeated relapses when nonadherent with medication. Requests for help can meet with what feels like an inadequate response from services. When help is offered, service users and caregivers find that the service user seems to lose the right to be heard as a result of their sectioned status. They learn to pretend that they are adherent to medication so as to regain some sense of control, but they also come to accept their experience as being an illness. They want help to deal with this illness, but find that there are two potential care pathways. Whether they receive competent and therapeutic care is dependent upon the attitudes and communication styles of the professionals they meet. In turn, this influences their ability to cooperate with care. Where they have been listened to and care is provided in a collaborative manner, they can cooperate and adhere to prescribed medication. When they are not listened to, care can take the form of intolerable medication regimes. The key task is therefore working through the system to find the professionals who will listen and provide helpful care.

Core category: the double-edged process of mental health medication adherence

In grounded theory, one existing or new core category eventually emerges through selective coding as the overarching explanatory narrative.Citation39 Within this study, the tale of related categories has two potential outcomes – “collaborative decision making mode enabling cooperation,” or “noncol-laborative mode disabling cooperation.” This study suggests that the core category, “the double-edged process of mental health medication adherence,” encompasses and explains the process of reaching a situation where medication adherence becomes possible (see ). Ambiguity was a feature of mental health care and service users and caregivers could not rely on that care to be acceptable and effective. Service user feedback suggested that the researchers needed to weight this aspect more heavily. Therefore, the final category emphasizes the potential paradox of the process of medication adherence.

Discussion

As discussed in the literature, mental health services should care for service users but also fulfill a social control function.Citation2 Professionals need to be aware of their dual roles and inherent power. Neglect of the listening and caring facets of mental health provision may result in service users feeling unable to cooperate with treatment. Previous research has demonstrated that increasing coercion may not improve outcomes.Citation21

Policy and practice emphasize the need to work collaboratively with service users.Citation17 However, despite recognizing their need for treatment (including acceptable medication), service users in this study described not being able to depend on provisioning consistently helpful mental health care; it has been suggested that care can be double-edged in other areas of service provision as well. The different faces of provisioned services labeled as care for older people may differ so much as to be completely conflicting in both nature and in result.Citation44 Others also describe policies and practices that are double-edged with unintended consequences.Citation45 Although these aim to provide something beneficial, at the same time their very existence may make the experience worse for the recipients of that service.

With many groups who have chronic or long term conditions, there are implicit issues of dependency and unequal power relations in their dealings with health services. There is concern at how mutual respect is compromised in the professional/service user relationship when the threat of legal compulsion is always present.Citation46 It is important that “the patient’s objective inequality” is not “transformed into a humiliating situation.”Citation47 It is acknowledged that although the professional/service user relationship can never be one of equals, it can attain a helpful position of mutual respect.Citation48 The task of collaboration can be problematic between groups with differing perspectives.Citation49 It is therefore imperative that professionals strive to understand how medication adherence and collaboration with care is perceived by service users and caregivers. This study emphasizes the need to recognize that care combined with compulsion can be a double-edged sword. Excessive concentration on medication adherence alone can be counterproductive. Service users in this research indicated that adherence is enabled by collaborative care with professionals who listen to them and enable them to take helpful medication.

Limitations

This is a relatively small-scale study and makes no claim to generalize. Findings are substantive to the group studied. However, they do support and add detail to other research in this area. Service users were not part of the research team but were part of the advisory and feedback process.

Conclusion

Mental health law on medication adherence has been extended in many parts of the world. Therefore, mental health professionals and service users have new challenges in managing interactions around adherence. There is a need to increase awareness of factors influencing service users’ ability to tolerate and be helped by medication. This research focused on interview and focus group data from those who had experience with compulsory treatment and the impacts of mental health law. It explains the process of attempting to find effective care and tolerable medication from the service user perspective. Service users (and their caregivers) accept their need for assistance, but they too often struggle to find it offered in a satisfactory manner. Ultimately, both service users and practitioners are or should be seeking a cooperative and constructive relationship. This outcome has proved difficult to achieve as highlighted by the documented concern about medication nonadherence and compulsory treatment in most of the developed world. Service users and caregivers have very real concerns about the benefits and effects of medication and require help in managing adherence. The findings of research such as this paper should enable service users’ perspectives to be heard and practitioners to hear their feedback.

Acknowledgments

The late Professor Paul Wainwright of Kingston University must be thanked and acknowledged as his insights, wit and supervision were major contributions to the completion of this work. Data were collected as part of a PhD program, partially funded by the Faculty of Health and Social Care Sciences, Kingston University and St George’s, University of London. Acknowledgments and huge thanks are also due to the service user and caregiver participants who gave their time and experience to this project.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SjöströmSZetterbergLMarkströmUWhy community compulsion became the solution – reforming mental health law in SwedenInt J Law Psychiatry201134641942822104265

- PilgrimDKey Concepts in Mental Health2nd edLondonSage Publications Ltd2009

- BellSJAiraksinenMSLylesAChenTFAslaniPConcordance is not synonymous with compliance or adherenceBr J Clin Pharmacol200764571071317875196

- DibonaventuraMGabrielSDupclayLGuptaSKimEA patient perspective of the impact of medication side effects on adherence: results of a cross sectional nationwide survey of patients with schizophreniaBMC Psychiatry201212202822433036

- MasandPSRocaMTurnerMSKaneJMPartial adherence to antipsychotic medication impacts the course of illness in patients with schizophrenia: a reviewPrim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry200911414715419750066

- Great BritainElizabeth 11 Mental Health Act Section 17a (5)LondonThe Stationery Office2007

- SharkeyPThe Essentials of Community Care2nd edBasingstokePalgrave Macmillan2007

- ReithMCommunity Care Tragedies: a Practical Guide to Mental Health InquiriesBirminghamVenture Press1998

- OrrJHoughABexleyheath stabbing murder suspect left mental health unit an hour beforeThe Telegraph Newspaper10112011 Available at http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/crime/8819896/Bexleyheath-stabbing-murder-suspect-left-mental-health-unit-an-hour-before-attack.htmlAccessed October 13, 2011

- WalkerPPolice missed checks on woman who went on to killThe Guardian342013 Available at http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2013/mar/04/police-woman-stabbing-nicola-edgingtonAccessed March 4, 2013

- LargeMSmithGSwinsonNShawJNielssenOHomicide due to mental disorder in England and Wales over 50 yearsBr J Psych20081932130133

- ApplebyLKapurNShawJThe National Confidential Enquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness: Annual Report July 2012ManchesterManchester University2012

- BrandlEFrydrychowiczCTiwariAAssociation study of polymorphisms in leptin and leptin receptor genes with antipsychotic-induced body weight gainProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry201238213414122426215

- FujikawaMTakashiTYoshimiAEvaluation of subjective treatment satisfaction with antipsychotics in schizophrenia patientsProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry200832375576018226436

- CorrellCULenczTMalhotraAKAntipsychotic drugs and obesityTrends Mol Med20101729710721185230

- VandykADBakerCQualitative study exploring schizophrenia and the everyday effect of medication-induced weight gainInt J Ment Health Nurs201221434935722404848

- Centre for Mental Health, Department of Health, Mind, NHS Confederation Mental Health Network, Rethink Mental Illness, Turning PointNo Health Without Mental Health: Implementation FrameworkLondonDepartment of Health Publications2012

- AronsonJKTime to abandon the term ‘patient concordance’Br J Clin Pharmacol2007645711713

- O’GradyLJadadAShifting from shared to collaborative decision making: a change in thinking and doingJournal of Participatory Medicine20102e13

- KiselySRXiaoJPrestonNJImpact of compulsory community treatment on admission rates: survival analysis using linked mental health and offender databasesBr J Psychiatry200418443243815123508

- KiselySRCampbellLAPrestonNJCompulsory community and involuntary outpatient treatment for people with severe mental disordersCochrane Database Syst Rev20112CD00440821328267

- OzgulSBruneroSA pilot study of the utilisation and outcome of community orders: client, case manager and Mental Health Review Tribunal perspectiveAust Health Review19972047083

- GibbsADawsonJMullenRCommunity treatment orders for people with serious mental illness: a New Zealand studyBritish Journal of Social Work20063610851100

- OlofssonBJacobssonLA plea for respect: involuntarily hospitalized psychiatric patients’ narratives about being subjected to coercionJ Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs20018435736611882148

- CanvinKBartlettAPinfoldVA ‘bittersweet pill to swallow’: learning from mental health service users’ responses to compulsory community care in EnglandHealth Soc Care Community200210536136912390222

- O’ReillyRLKeeganDLCorringDShrikhandeSNatarajanDA qualitative analysis of the use of community treatment orders in SaskatchewanInt J Law Psychiatry200629651652417083974

- BauerMSBiswasKKilbourneAMEnhancing multiyear guideline concordance for Bipolar Disorder through collaborative careAm J Psychiatry2009166111244125019797436

- National Institute for Health and Clinical ExcellenceSchizophrenia: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Adults in Primary and Secondary CareLondon (UK)National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence2009

- KusumiIItoKUemuraKScreening for diabetes using monitoring guidance in schizophrenia patients treated with second generation antipsychotics: a 1 year follow-up studyProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry20113581922192621807061

- ChurchillROwenGSinghSHotopfMInternational Experiences of using Community Treatment OrdersLondon (UK)Department of Health Services Research, Institute of Psychiatry, Kings College2007

- KallapiranKSankaranarayananALewinTA pilot investigation of the relationship between community treatment orders and hospital utilization ratesAustralas Psychiatry201018650350521117836

- BurnsTRugkasaJMolodynskiAThe Oxford community treatment order evaluation trial (OCTET)The Psychiatrist200932400

- O’BrienAJMcKennaBGKyddRRCompulsory mental health legislation; a literature reviewInternational Journal of Nursing Studies20094691245125519296950

- RynorBValue of community treatment orders remains at issueCMAJ20101828337338

- RivasCCoding and analysing qualitative dataSealeCResearching Society and Culture3rd edLondonPublications Ltd2012366392

- SealeCResearching Society and Culture3nd edLondonSage Publications Ltd2012

- CharmazKConstructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative AnalysisLondonSage Publications Ltd2006

- DeyIMiddle aged grounded theorySealeCGiampietroGGubriumGFSilvermanDQualitative Research PracticeLondonPublications Ltd20048093

- StraussACorbinJMBasics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing GroundedLondonSage Publications Ltd1998

- GlaserBStraussAThe Discovery of Grounded TheoryChicagoAldine Publishing Co1967

- KelleUThe development of categories: different approaches in grounded theoryBryantACharmazKThe Sage Handbook of Grounded TheoryLondonSage Publications Ltd2007191213

- GoboGSampling, representativeness and generalisabilitySealeCGoboGGubriumJFSilvermanDQualitative Research PracticeLondonSage Publications Ltd2004435456

- FlickUAn Introduction to Qualitative Research4th edLondonSage Publications Ltd2009

- SimmsMOpening the black opening the black box of rationing care in later life: the case of ‘community care’ in BritainJ Aging Health200315471373714594025

- VeridrameGHarrel-BondBRights in Exile: Janus-Faced HumanitarianismNew YorkBergahan Books2005

- WarneTKeelingJMcAndrewSMental health law in EnglandBarkerPMental Health Ethics: The Human ContextLondonRoutledge2011275285

- GirardMTechnical expertise as an ethical form: towards an ethics of distanceJ Med Ethics199814125303351879

- SennettRRespect in a World of InequalityNew YorkWW Norton and Company2003

- SennettRTogether: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of CooperationLondonAllen Lane2012