Abstract

When treating persons with schizophrenia, delaying time to relapse is a main goal. Antipsychotic medication has been the primary treatment approach, and there are a variety of different choices available. Lurasidone is a second-generation (atypical) antipsychotic agent that is approved for the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar depression. Three long-term studies of lurasidone have examined time to relapse in persons with schizophrenia, including a classic placebo-controlled randomized withdrawal study and two 12-month active comparator studies (vs risperidone and vs quetiapine extended-release). Lurasidone 40–80 mg/d evidenced superiority over placebo (number needed to treat [NNT] vs placebo for relapse, 9). Lurasidone 40–160 mg/d was noninferior to quetiapine extended-release 200–800 mg/d on the outcome of relapse, and was superior on the outcome of avoidance of hospitalization (NNT 8) and the outcome of remission (NNT 7). Lurasidone demonstrated a lower risk for long-term weight gain than the active comparators. Demonstrated differences in tolerability profiles among the different choices of antipsychotics make it possible to attempt to match up an individual patient to the best choice for such patient based on past history of tolerability, comorbidities, and personal preferences, potentially improving adherence.

Introduction

Optimal management of schizophrenia requires adequate symptom control and avoidance of exacerbation or relapse. Unfortunately, relapse is common, with an estimate of ≥80% of patients experiencing a relapse in their first 5 years of treatment.Citation1 Delaying time to relapse is a primary goal when using antipsychotic medication, and may mitigate against further decline.Citation2 Lifelong use of antipsychotic medication is thus required.Citation3 Unfortunately, antipsychotic medications are associated with a myriad of adverse effects.Citation4,Citation5 Demonstrated differences in tolerability profiles among the different choices of antipsychoticsCitation6 make it possible to attempt to match up an individual patient to the best choice for such patient based on past history of tolerability, comorbidities, and personal preferences.Citation7,Citation8

Lurasidone is a second-generation (atypical) antipsychotic agent that has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, and it is approved as such in the United States, Canada, the European Union, Switzerland, and Australia; it is also approved in the United States and Canada for the treatment of major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder as either a monotherapy or adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate.Citation9 Lurasidone’s pharmacodynamic profile is distinguished by its relatively high affinity for serotonin 5-HT7 receptors and its partial agonist activity at 5-HT1A receptors, together with being a full antagonist at dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT2A receptors.Citation9 Lurasidone’s pharmacokinetic profile permits once-daily dosing, and administration needs to be with food; it is recommended that lurasidone be taken once daily in the evening, with a meal or within 30 minutes after eating.Citation9 Metabolism is primarily via CYP3A4 and, consequently, its use is contraindicated in the presence of strong inhibitors or inducers of CYP3A4 such as ketoconazole or rifampin, respectively.Citation9 Lurasidone appears associated with minimal effects on body weight and low risk for clinically meaningful alterations in glucose, lipids, or electrocardiogram parameters.Citation9

This review examines the lurasidone data regarding relapse prevention in persons with schizophrenia, specifically appraising the results from double-blind controlled trials.

Methods

A literature search was conducted on June 14, 2016, using the following terms “lurasidone AND relapse” using the US National Library of Medicine PubMed.gov resource. A total of 22 records were found, of which three were primary reports of double-blind randomized trials,Citation10–Citation12 and one was an economic evaluationCitation13 of one of the studies reported.Citation11 One of the studies was a classic randomized withdrawal placebo-controlled relapse prevention study,Citation12 whereas the other two studies compared lurasidone with quetiapine extended-release (XR)Citation11 and risperidone.Citation10 These reports,Citation10–Citation12 together with any study results posted on the ClinicalTrials.gov registry, were the principal information sources for this review.

Results

provides an overview of the three relevant studies: Citrome et al,Citation10 Loebel et al,Citation11 and Tandon et al.Citation12 Doses of lurasidone tested were in the range of 40–160 mg/d.

Table 1 Double-blind randomized studies of lurasidone examining relapse in persons with schizophrenia

NCT00641745

The first published randomized double-blind study of lurasidone that included relapse as an outcome measure was a 12-month safety and tolerability study where 629 persons, aged between 18 and 75 years, with clinically stable schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, were allocated to receive flexibly dosed lurasidone 40–120 mg/d (n=427) or risperidone 2–6 mg/d (n=202).Citation10 The study was conducted at 68 study centers located primarily in the United States (40 sites; approximately two-thirds of all participants), but also recruited patients in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Croatia, Israel, South Africa, and Thailand. Inclusion criteria included the following: duration of illness ≥1 year; in a nonacute phase of illness for ≥8 weeks; no change in antipsychotic medications, other than minor dose adjustments for tolerability purposes, for ≥6 weeks before screening; no hospitalization for psychiatric illness for ≥8 weeks; and moderate or less severity rating on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) items of delusions, conceptual disorganization, hallucinations, and unusual thought content. Among the exclusion criteria were treatment with risperidone within 6 weeks before baseline, or a history of a poor or an inadequate response, or intolerability to risperidone. Patients who had been treated with a stable dose of antidepressants or mood stabilizers for ≥1 month before the baseline visit were allowed to continue this treatment during the study; otherwise, subjects were not permitted to begin treatment with these agents after the screening visit. Although the primary outcome measure was the number of participants with adverse events, efficacy outcomes included relapse rate, PANSS total score, and the Clinical Global Impressions-Severity (CGI-S) score. Relapse was defined as worsening of the PANSS total score by 30% from baseline and CGI-S >3; rehospitalization for worsening of psychosis; or emergence of suicidal ideation, homicidal ideation, and/or risk of harm to self or others.

Relapse

A small proportion of subjects in the study experienced a relapse (114/608, 19%). The rate of relapse among lurasidone-treated patients was 20% (82/410), and that for risperidone-treated patients, 16% (32/198), yielding a number needed to treat (NNT) value of 27 (not statistically significant [ns]) in favor of risperidone (for a brief overview of NNT, see Box 1). For both treatment groups, the Kaplan–Meier estimates of the probability of relapse were less than 0.5 at month 12; therefore, the median survival time to relapse could not be calculated for either treatment group. The relapse hazard ratio comparing lurasidone vs risperidone was 1.31 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.87–1.97; P=0.194). Because the study was powered to test the noninferiority of lurasidone relative to risperidone on the basis of the assumption of expected relapse rates of 35% for both treatment groups after 1 year, the noninferiority test was uninterpretable because the actual relapse rates were substantially lower than initially predicted.

An NNT is a measure of effect size that is clinically intuitive. NNT answers the question: “How many patients would you need to treat with Intervention A instead of Intervention B before you would expect to encounter one additional positive outcome of interest?” For the outcome of avoidance of relapse, an NNT of “x” for a test medication vs placebo would mean you would have to treat “x” number of patients with the test medication instead of with placebo before expecting to avoid one additional relapse. The lower the NNT, the more robust the intervention is when compared to the alternative. NNT is a different concept than P-value, which relates to “statistical” significance. NNT is a measure of “clinical” significance. A P-value, even as low as P<0.00001, does not necessarily mean that a result is clinically relevant. To determine possible clinical relevance (ie, clinical significance) effect size, such as NNT, needs to be evaluated.

NNT is simple to calculate:

A = frequency of outcome for Intervention A

B = frequency of outcome for Intervention B

NNT =1/(A–B), rounded up to a whole number

For example, if giving a test medication results in relapse of 25% over a 12-month period and giving placebo results in relapse of 50% over a 12-month period, NNT for avoidance of relapse for the test medication vs placebo is 1/(50%–25%)=1/(0.50–0.25)=1/(0.25)=4. Thus, for every four persons given the test medication instead of placebo, you would expect to avoid one additional relapse event.

A rule of thumb is that NNT values vs placebo <10 denote potentially useful interventions. Most psychotropic medications for most indications have NNT values between 3 and 9 for clinically relevant definitions of response or efficacy. The lower the NNT, the more often desired outcomes are encountered.

An additional tutorial for the use of NNT can be found at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4140623/ and guidance on interpretation is further available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ijcp.12142/full. Both of these resources are free to access.

Abbreviation: NNT, number needed to treat.

Other efficacy outcomes

The PANSS total score decreased from baseline to month 12 in both the lurasidone group (−4.7; 95% CI: −6.4 to −3.0) and the risperidone group −6.5; 95% CI: −8.8 to −4.3), with no significant differences between lurasidone and risperidone in the PANSS total scores at any time during the 12-month double-blind treatment period. Similarly, the CGI-S score decreased from baseline to month 12 similarly in both the lurasidone group (−0.4; 95% CI: −0.5 to −0.3) and the risperidone group (−0.4; 95% CI: −0.5 to −0.2).

Tolerability outcomes

The three most frequent adverse events among the lurasidone-treated patients (vs risperidone) were nausea (17% vs 11%), insomnia (16% vs 13%), and sedation (15% vs 14%); the three most frequent adverse events in the risperidone-treated patients (vs lurasidone) were increased weight (20% vs 9%), somnolence (18% vs 14%), and headache (15% vs 10%). The rates of akathisia reported by patients as an adverse event were 14% and 8% in the lurasidone and the risperidone groups, respectively; rates of discontinuation because of akathisia were low in both groups (1.0% of lurasidone patients and 1.5% of risperidone patients). Risperidone was more likely to result in body weight gain of ≥7%, as observed in 14% of subjects receiving risperidone vs 7% for lurasidone-treated patients. Endpoint change in prolactin was also higher with the risperidone group. All-cause discontinuation rates were higher for lurasidone vs risperidone: 269/419 (64%) for lurasidone and 105/202 (52%) for risperidone in the safety population, resulting in an NNT of 9 (95% CI: 5–26) in favor of risperidone. However, there were no significant treatment differences for the time to discontinuation because of insufficient clinical response, an adverse event, or withdrawal of consent.

NCT00789698

A second long-term study that contrasted lurasidone with an active comparator was a 12-month double-blind extensionCitation11 to a 6-week placebo-controlled acute treatment trial.Citation14 Enrolled were 292 persons with schizophrenia, aged between 18 and 75 years, who received either flexibly dosed lurasi-done 40–160 mg/d (n=207) or quetiapine XR 200–800 mg/d (n=85).Citation11 The study was conducted at 58 centers in six countries, with approximately one-quarter of all participants being from the United States. The primary relapse prevention analysis population was defined as all subjects who were randomized to either once-daily fixed doses of lurasidone (80 or 160 mg) or quetiapine XR 600 mg in the initial 6 week acute treatment study and who met clinical response criteria at the end of that study. Response was defined as ≥20% reduction in PANSS total score from acute study baseline and a CGI-S ≤4. A total of 139 subjects receiving lurasidone and 79 subjects receiving quetiapine XR were included in the primary noninferiority analysis for relapse prevention. Relapse was defined as worsening of ≥30% in the PANSS total score from day 42 of the initial acute treatment study and a CGI-S ≥3; rehospitalization for worsening of psychosis; or emergence of suicidal ideation, homicidal ideation, and/or risk of harm.

Relapse

The rate of relapse among lurasidone-treated patients was 21% (29/139), and that for quetiapine-treated patients, 27% (21/79), yielding a number NNT of 18 (not statistically significant) in favor of lurasidone. For both treatment groups, the Kaplan–Meier estimates of the probability of relapse were less than 0.5 at month 12; therefore, the median survival time to relapse could not be calculated for either treatment group. The relapse hazard ratio comparing lurasidone vs quetiapine was 0.73 (95% CI: 0.41–1.30), demonstrating noninferiority.

Other efficacy outcomes

An advantage was found for lurasidone regarding hospitalization risk. The Kaplan–Meier estimate of the probability of hospitalization at 12 months was significantly lower for lurasidone vs quetiapine XR, at 10% vs 23% (NNT 8; 95% CI: 5–37; P<0.05), resulting in a hazard ratio of 0.43 (95% CI: 0.19–1.0). More patients on lurasidone achieved remission, as defined by Andreasen et al,Citation15 compared to patients receiving quetiapine XR with rates of 62% vs 46%, respectively, resulting in an NNT of 7 (95% CI: 4–52). There was significantly greater change in the PANSS total score from the 12-month study baseline for lurasidone-treated patients than for patients treated with quetiapine XR (−5.0 vs +1.7); however, changes in CGI-S scores were similar.

Tolerability outcomes

The three most frequent adverse events in the lurasidone-treated group were akathisia (13%), headache (11%), and insomnia (8%); the three most frequent adverse events in the quetiapine XR group were worsening of schizophrenia (15%), insomnia (9%), and headache (9%). The rates of akathisia reported by patients as an adverse event were 11% and 2% in the lurasidone and the quetiapine XR groups, respectively (and 13% among those initially on placebo in the parent study and then switched to lurasidone in the 12-month study). Quetiapine XR was more likely to result in weight gain of ≥7%, with this outcome observed in 27.5% of subjects receiving quetiapine XR vs 14% for lurasidone-treated patients at 6 months, and 15% vs 11.5% at 12 months, respectively, for observed cases. Rates of discontinuation due to adverse events were similar: 7% for lurasidone-treated patients and 5% for patients receiving quetiapine XR.

Other publications

Additional publications identified in PubMed.gov by searching on the ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00789698 have reported on improved cognitive performance in patients treated with lurasidone compared to quetiapine XR.Citation16,Citation17 An economic impact study has also been published, demonstrating cost savings with lurasidone over quetiapine, driven by the lower relapse-related hospitalization rates observed with lurasidone.Citation13

NCT01435928

A classic randomized withdrawal study has been published where 285 persons with schizophrenia, aged 18–75 years, met protocol-specified stabilization criteria and were randomized to receive lurasidone 40–80 mg/d (n=144) or placebo (n=141) for up to 28 weeks.Citation12 The study was conducted at 71 sites in seven countries, with 45 of the study sites located in the United States and comprising approximately 70% of all participants. Subjects were initially enrolled in an open-label stabilization phase where 676 acutely ill patients received 12–24 weeks of treatment with lurasidone at a starting dose of 40 mg/d, with flexible dosing permitted after 3 days up until the last 4 weeks of the stabilization period, during which no dose adjustments were permitted. Treatment with antidepressant medications or mood stabilizers was allowed in patients who had been taking a stable dose for ≥30 days prior to the open-label stabilization phase baseline; however, initiation or increase in dosage of these medications during the study was prohibited. The protocol-specified stabilization criteria were that subjects maintained clinical stability for ≥12 weeks during the open-label stabilization phase and had remained on a stable dose of lurasidone for 4 weeks prior to randomization. Clinical stability was defined as a PANSS total score ≤70, with PANSS item scores ≤4 on all positive subscale items and the general psychopathology item for uncooperativeness, and a CGI-S score <4. There was some flexibility to retain subjects if they had temporary increases in their total PANSS score (up to 80), CGI-S of 4, or a PANSS positive item of 5; two such events were allowed after initial attainment of the stability criteria, except during the last 4 weeks of the open-label stabilization phase. Once randomized, lurasidone dose was the same as the final open-label dose but adjustments within the range of lurasidone 40–80 mg/d were subsequently allowed. Relapse was defined as an increase of ≥25% from double-blind baseline in PANSS total score and CGI-S worsening of ≥1 point for two consecutive visits no more than 10 days apart; at any single visit, a PANSS item score of ≥5 (moderately severe) on hostility or uncooperativeness, or a PANSS item score of ≥5 on two or more items of unusual thought content, delusions, conceptual disorganization, or hallucinatory behavior; initiation of supplemental treatment with an antipsychotic medication other than lurasidone, an increased dose of an antidepressant or mood stabilizer, an increase in lorazepam (or benzodiazepine equivalent) dose by ≥2 mg/d for at least 3 days, or electroconvulsive therapy; insufficient clinical response or exacerbation of underlying disease reported as an adverse event, as determined by the study investigator; deliberate self-injury or repeated aggressive behavior, active suicidal or homicidal ideation or attempt; or psychiatric hospitalization due to worsening schizophrenia.

Relapse

The rate of relapse among lurasidone-treated patients was 30% (43/144), and that for placebo-treated patients, 41% (58/141), yielding an NNT of 9 (95% CI: 5–426) in favor of lurasidone. The Kaplan–Meier estimates of the probability of relapse at week 28 were 42% for patients receiving lurasidone and 51% for the placebo group, with a median survival time to relapse of about 28 weeks for subjects receiving placebo, and it was not calculable for patients randomized to continue treatment with lurasidone. The relapse hazard ratio comparing lurasidone vs placebo was 0.66 (95% CI: 0.45–0.98), demonstrating superiority.

Other efficacy outcomes

Patients in the placebo-treated group evidenced worsening in PANSS total and CGI-S scores compared to patients receiving lurasidone. Of note, differences in efficacy outcomes were noted when comparing US with non-US sites; lurasidone significantly delayed time to relapse in the non-US subgroup (n=85, log-rank test, P=0.010) but not in the US subgroup (n=200, log-rank test, P=0.414).

Tolerability outcomes

In the open-label stabilization phase, the most common adverse events were akathisia (14%), headache (11%), and nausea (10%). In the double-blind phase, the three most frequent adverse events in the lurasidone-treated group were schizophrenia (8%), insomnia (6%), and anxiety or back pain (4% each); the three most frequent adverse events in the placebo group were schizophrenia (9%), insomnia (7%), and headache (3.5%). Rates of akathisia in the double-blind phase were 2.1% for subjects receiving lurasidone and 2.8% for those receiving placebo. The discontinuation rate due to adverse events (including the adverse event-related relapse criterion of worsening of schizophrenia) during the double-blind phase was 14% for lurasidone and 16% for placebo. Minimal changes in weight, lipids, glucose, and prolactin were observed. Moreover, in the patients treated with lurasidone, mean weight change was −0.6 kg as observed across the open-label and randomized phases, with weight gain ≥7% and weight loss ≥7% experienced by a similar proportion of patients (17.4% and 16.7%, respectively). All-cause discontinuation rates were 48% and 58%, for lurasidone- and placebo-treated subjects, respectively, resulting in an NNT of 10 (ns), with a Kaplan–Meier probability of all-cause discontinuation at the week 28 endpoint of 58% for the lurasidone group vs 70% for placebo (log rank test, P=0.070).

Discussion

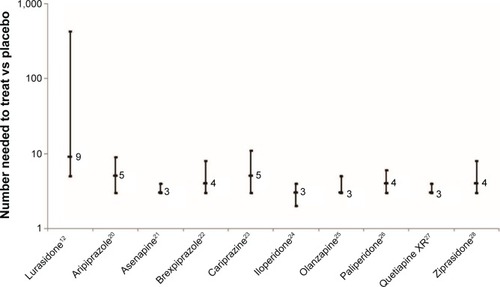

The efficacy of lurasidone for the maintenance treatment of patients with schizophrenia was tested in three multicenter, randomized, controlled trials,Citation10–Citation12 including a placebo-controlled, randomized withdrawal study.Citation12 Superiority to placebo and noninferiority to quetiapine XR has been evidenced, with an uninterpretable relapse outcome when lurasidone was compared with risperidone. Doses tested span the range of that available for lurasidone, 40–160 mg/d; however, the placebo-controlled trial was limited to 80 mg/d.Citation12 This is somewhat problematic as it is apparent that some patients may require higher doses in the face of inadequate response to 80 mg/d.Citation18,Citation19 This limitation in lurasidone dose in the placebo-controlled randomized withdrawal study, together with possible study-conduct problems at US sites (given the lack of signal detection in the United States vs outside the United States), may have led to the observed effect size that is less robust (and less precise) than reported for other similar studies with other second-generation antipsychotics (),Citation20–Citation28 and as noted in a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies of antipsychotic agents for relapse prevention in patients with schizophrenia, which found from data published from 1962 to 2010, across 24 randomized trials, that treatments reduced relapse rates at around 1 year (7–12 months) from 64% (placebo) to 27% (risk ratio: 0.40; 95% CI: 0.33–0.49; risk difference: −39%; 95% CI: −46 to −32), for an NNT of 3.Citation29,Citation30 depicts the NNT vs placebo and 95% CIs for the outcome of relapse (or impending relapse) from data that have been published (or recently presented) of pivotal placebo-controlled randomized withdrawal studies of the oral first-line second-generation antipsychotics (there is no available study for quetiapine immediate-release or risperidone). Indirect comparison reveals a degree of overlap for the 95% CIs among the agents, including lurasidone vs aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, olanzapine, paliperidone, and ziprasidone. Although there is no overlap in the 95% CIs for lurasidone vs quetiapine XR, this indirect comparison is difficult to interpret, particularly in the face of noninferiority for probability of relapse that was observed when lurasidone was directly compared with quetiapine XR.Citation11 An important caveat is that randomized withdrawal studies can differ substantially in terms of open-label stabilization periods (if any), stabilization criteria, length of observation, and relapse criteria. The efficacy profile for each alternative also needs to be considered within the context of tolerability and safety.Citation8 For example, as observed in the relapse-prevention studies of lurasidone, although lurasidone was associated with generally higher rates of akathisia, quetiapine XR and risperidone were more likely to result in weight gain.

Figure 1 NNT vs placebo and 95% CIs for the outcome of relapse (or impending relapse) from available data from the pivotal placebo-controlled randomized withdrawal studies of the oral first-line second-generation antipsychotics (there is no available study for quetiapine immediate-release or risperidone).

Table 2 Placebo-controlled randomized withdrawal studies of first-line oral second-generation antipsychotics in persons with schizophrenia

The maintenance of a therapeutic response with long-term use of lurasidone for schizophrenia is also supported by several open-label extension studies of up to 22 months in duration.Citation31–Citation33 The long-term effect of lurasidone 40–160 mg/d on body weight after 12 months of treatment in persons with schizophrenia was examined in a pooled analysis of 593 observed cases;Citation34 subjects were participants from the two 12-month randomized studies reviewed here,Citation10,Citation11 combined with data from a 22-month open-label extension study,Citation31 a 12-month extension study (NCT00088621), a Japanese 44-week open-label extension of a 8-week double-blind study, and a Japanese 12-month open-label study that enrolled acute patients. Mean baseline weight was 72.8, 80.8, and 72.4 kg in the lurasidone (n=471), risperidone (n=89), and quetiapine XR (n=33) groups, respectively. At the end of 1 year, mean weight change was −0.4 kg with lurasidone, +2.6 kg with risperidone, and +1.2 kg with quetiapine XR. Weight gain ≥7% was seen in 16%, 26%, and 15% of patients, while weight loss ≥7% was observed in 18.5%, 7%, and 9%, respectively. Lurasidone thus appears to have a lower risk for long-term weight gain than some other second-generation antipsychotics, and these data are consistent with that observed in short-term acute clinical trials for both schizophreniaCitation35 and bipolar depressionCitation36 and in the 24-week open-label extension study for bipolar depression.Citation37 Body weight is easily monitored during routine office visits, and avoiding overweight and obesity is an important strategy in managing risk for metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.Citation38 Patients with weight gain may be less likely to be adherent to their prescribed medications as observed in a nationwide survey of 876 US adults with schizophrenia and taking antipsychotic medication, where about 26% reported bothersome weight gain.Citation39

Studies examining quality-of-life improvements among persons with schizophrenia treated with lurasidone have been published.Citation40,Citation41 In a 24-week extensionCitation32 of an open-label 6-week switch study,Citation42 health-related quality of life was measured using the self-reported Personal Evaluation of Transitions in Treatment scale and Short-Form 12 questionnaire; improvements were observed on both of these measures, including components assessing adherence-related attitude and psychosocial functioning.Citation41

No singular medication is perfect for everyone.Citation8 Additional choices for antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia are also desirable to accommodate the wide range of preexisting tolerability issues that patients may have.Citation43 Consideration should also be given to other formulations, such as long-acting injectables, particularly in the maintenance phase of treatment, assuming the suitability of the currently available options for the individual person being treated.Citation44

In summary, the overall available data support the use of lurasidone for relapse prevention. Long-term safety and tolerability mirrors that observed during short-term acute trials, with advantages in terms of a more favorable weight gain profile than many other available choices,Citation6,Citation7 and consequently a lower risk for problematic alterations in lipid profile and the development of insulin resistance.

Disclosure

No writing assistance or external financial support was utilized in the production of this article. In the past 36 months, Leslie Citrome has engaged in collaborative research with, or received consulting or speaking fees, from: Acadia, Alexza, Alkermes, Allergan, AstraZeneca, Avanir, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Forum, Genentech, Janssen, Jazz, Lundbeck, Merck, Medivation, Mylan, Neurocrine, Novartis, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Reckitt Benckiser, Reviva, Shire, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, Valeant, and Vanda. The author reports no other conflicts of interests in this work.

References

- RobinsonDWoernerMGAlvirJMPredictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorderArch Gen Psychiatry199956324124710078501

- WiersmaDNienhuisFJSlooffCJGielRNatural course of schizophrenic disorders: a 15-year follow up of a Dutch incidence cohortSchizophr Bull199824175859502547

- EmsleyRChilizaBAsmalLHarveyBHThe nature of relapse in schizophreniaBMC Psychiatry2013135023394123

- MuenchJHamerAMAdverse effects of antipsychotic medicationsAm Fam Physician201081561762220187598

- BruijnzeelDSuryadevaraUTandonRAntipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia: an updateAsian J Psychiatr2014113725216917

- LeuchtSCiprianiASpineliLComparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysisLancet2013382989695196223810019

- CitromeLA review of the pharmacology, efficacy and tolerability of recently approved and upcoming oral antipsychotics: an evidence-based medicine approachCNS Drugs2013271187991124062193

- VolavkaJCitromeLOral antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia: heterogeneity in efficacy and tolerability should drive decision-makingExpert Opin Pharmacother200910121917192819558339

- LoebelACitromeLLurasidone: a novel antipsychotic agent for the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar depressionBJPsych Bull201539523724126755968

- CitromeLCucchiaroJSarmaKLong-term safety and tolerability of lurasidone in schizophrenia: a 12-month, double-blind, active-controlled studyInt Clin Psychopharmacol201227316517622395527

- LoebelACucchiaroJXuJSarmaKPikalovAKaneJMEffectiveness of lurasidone vs. quetiapine XR for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a 12-month, double-blind, noninferiority studySchizophr Res201314719510223583011

- TandonRCucchiaroJPhillipsDA double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized withdrawal study of lurasidone for the maintenance of efficacy in patients with schizophreniaJ Psychopharmacol2016301697726645209

- RajagopalanKO’DayKMeyerKPikalovALoebelAAnnual cost of relapses and relapse-related hospitalizations in adults with schizophrenia: results from a 12-month, double-blind, comparative study of lurasidone vs quetiapine extended-releaseJ Med Econ201316898799623742620

- LoebelACucchiaroJSarmaKEfficacy and safety of lurasidone 80 mg/day and 160 mg/day in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trialSchizophr Res20131451–310110923415311

- AndreasenNCCarpenterWTJrKaneJMLasserRAMarderSRWeinbergerDRRemission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensusAm J Psychiatry2005162344144915741458

- HarveyPDSiuCOOgasaMLoebelAEffect of lurasidone dose on cognition in patients with schizophrenia: post-hoc analysis of a long-term, double-blind continuation studySchizophr Res20151661–333433826117157

- HarveyPDSiuCOHsuJCucchiaroJMaruffPLoebelAEffect of lurasidone on neurocognitive performance in patients with schizophrenia: a short-term placebo- and active-controlled study followed by a 6-month double-blind extensionEur Neuropsychopharmacol201323111373138224035633

- LoebelACitromeLCorrellCUXuJCucchiaroJKaneJMTreatment of early non-response in patients with schizophrenia: assessing the efficacy of antipsychotic dose escalationBMC Psychiatry20151527126521019

- LoebelASilvaRGoldmanRLurasidone dose escalation in early nonresponding patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, placebo-controlled studyJ Clin Psychiatry2016719 Epub ahead of print

- PigottTACarsonWHSahaARAripiprazole for the prevention of relapse in stabilized patients with chronic schizophrenia: a placebo-controlled 26-week studyJ Clin Psychiatry20036491048105614628980

- KaneJMMackleMSnow-AdamiLZhaoJSzegediAPanagidesJA randomized placebo-controlled trial of asenapine for the prevention of relapse of schizophrenia after long-term treatmentJ Clin Psychiatry201172334935521367356

- FleischhackerWWHobartMOuyangJBrexpiprazole (OPC-34712) efficacy and safety as maintenance therapy in adults with schizophrenia: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyEur Neuropsychopharmacol201525Suppl 2S527

- DurgamSEarleyWLiRLong-term cariprazine treatment for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialSchizophr Res2016714 Epub ahead of print

- WeidenPJManningRWolfgangCDA randomized trial of iloperidone for prevention of relapse in schizophrenia: the REPRIEVE studyCNS Drugs Epub752016

- BeasleyCMJrSuttonVKHamiltonSHA double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine in the prevention of psychotic relapseJ Clin Psychopharmacol200323658259414624189

- KramerMSimpsonGMaciulisVPaliperidone extended-release tablets for prevention of symptom recurrence in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyJ Clin Psychopharmacol200727161417224706

- PeuskensJTrivediJMalyarovSPrevention of schizophrenia relapse with extended release quetiapine fumarate dosed once daily: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in clinically stable patientsPsychiatry (Edgmont)2007411345020428302

- AratoMO’ConnorRMeltzerHYZEUS Study GroupA 1-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ziprasidone 40, 80 and 160 mg/day in chronic schizophrenia: the Ziprasidone Extended Use in Schizophrenia (ZEUS) studyInt Clin Psychopharmacol200217520721512177583

- LeuchtSTardyMKomossaKHeresSKisslingWDavisJMMaintenance treatment with antipsychotic drugs for schizophreniaCochrane Database Syst Rev20125CD00801622592725

- LeuchtSTardyMKomossaKAntipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysisLancet201237998312063207122560607

- CorrellCUCucchiaroJSilvaRHsuJPikalovALoebelALong-term safety and effectiveness of lurasidone in schizophrenia: a 22-month, open-label extension studyCNS Spectr Epub462016

- CitromeLWeidenPJMcEvoyJPEffectiveness of lurasidone in schizophrenia or schizoaffective patients switched from other antipsychotics: a 6-month, open-label, extension studyCNS Spectr201419433033924330868

- StahlSMCucchiaroJSimonelliDHsuJPikalovALoebelAEffectiveness of lurasidone for patients with schizophrenia following 6 weeks of acute treatment with lurasidone, olanzapine, or placebo: a 6-month, open-label, extension studyJ Clin Psychiatry201374550751523541189

- MeyerJMMaoYPikalovACucchiaroJLoebelAWeight change during long-term treatment with lurasidone: pooled analysis of studies in patients with schizophreniaInt Clin Psychopharmacol201530634235026196189

- CitromeLLurasidone for the acute treatment of adults with schizophrenia: what is the number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed?Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses201262768522776634

- CitromeLKetterTACucchiaroJLoebelAClinical assessment of lurasidone benefit and risk in the treatment of bipolar I depression using number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmedJ Affect Disord2014155202724246116

- KetterTASarmaKSilvaRKrogerHCucchiaroJLoebelALurasidone in the long-term treatment of patients with bipolar disorder: a 24-week open-label extension studyDepress Anxiety201633542443426918425

- CitromeLBlondeLDamatarcaCMetabolic issues in patients with severe mental illnessSouth Med J200598771472016108240

- DibonaventuraMGabrielSDupclayLGuptaSKimEA patient perspective of the impact of medication side effects on adherence: results of a cross-sectional nationwide survey of patients with schizophreniaBMC Psychiatry2012122022433036

- AwadGHassanMLoebelAHsuJPikalovARajagopalanKHealth-related quality of life among patients treated with lurasidone: results from a switch trial in patients with schizophreniaBMC Psychiatry2014145324559217

- AwadGNg-MakDRajagopalanKHsuJPikalovALoebelALong-term health-related quality of life improvements among patients treated with lurasidone: results from the open-label extension of a switch trial in schizophreniaBMC Psychiatry20161617627245981

- McEvoyJPCitromeLHernandezDEffectiveness of lurasidone in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder switched from other antipsychotics: a randomized, 6-week, open-label studyJ Clin Psychiatry201374217017923473350

- CitromeLEramoAFrancoisCLack of tolerable treatment options for patients with schizophreniaNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2015113095310426719694

- CitromeLNew second-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophreniaExpert Rev Neurother201313776778323898849

- LoebelACucchiaroJXuJSarmaKPikalovAKaneJMEffectiveness of lurasidone vs quetiapine XR for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a 12-month, double-blind studyPoster presented at: American Psychiatric Association Annual MeetingMay 5–9, 2012Philadelphia, PA, USA