Abstract

Objectives

Several cross-sectional studies suggest that psychosocial factors are associated with non-adherence to chronic preventive maintenance medication (CPMM); however, results from longitudinal associations have not yet been systematically summarized. Therefore, the objective of this study was to systematically synthesize evidence of longitudinal associations between psychosocial predictors and CPMM non-adherence.

Materials and methods

PUBMED, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsychINFO databases were searched for studies meeting our inclusion criteria. The reference lists and the ISI Web of Knowledge of the included studies were checked. Studies were included if they had an English abstract, involved adult populations using CPMM living in Western countries, and if they investigated associations between psychosocial predictors and medication non-adherence using longitudinal designs. Data were extracted according to a literature-based extraction form. Study quality was independently judged by two researchers using a framework comprising six bias domains. Studies were considered to be of high quality if ≥four domains were free of bias. Psychosocial predictors for non-adherence were categorized into five pre-defined categories: beliefs/cognitions; coping styles; social influences and social support; personality traits; and psychosocial well-being. A qualitative best evidence synthesis was performed to synthesize evidence of longitudinal associations between psychosocial predictors and CPMM non-adherence.

Results

Of 4,732 initially-identified studies, 30 (low-quality) studies were included in the systematic review. The qualitative best evidence synthesis demonstrated limited evidence for absence of a longitudinal association between CPMM non-adherence and the psychosocial categories. The strength of evidence for the review’s findings is limited by the low quality of included studies.

Conclusion

The results do not provide psychosocial targets for the development of new interventions in clinical practice. This review clearly demonstrates the need for high-quality, longitudinal research to identify psychosocial predictors of medication non-adherence.

Introduction

In conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and hypertension, long-term therapy with chronic preventive maintenance medication (CPMM) is essential for reducing risks of disease progression, comorbidity, and mortality. However, sufficient medication adherence to CPMM is a prerequisite for reducing these risks.Citation1

Medication non-adherence, or the extent to which patients do not take their medications as agreed with their health care provider, averages 50% among patients suffering from chronic diseases in developed countries.Citation2 Non-adherence can result in poorer health outcomes and a lower quality of life in patients.Citation3 For example, patients who did not adhere to beta-blocker therapy were four and a half times more likely to have complications from coronary heart disease than those who adhered to therapy.Citation4 Non-adherence also affects health care utilization. For instance, poorer adherence among elderly patients with moderate-to-severe asthma was associated with a 5% increase in annual physician visits, whereas better adherence was associated with a 20% decrease in annual hospitalization.Citation5

Considering the undesired consequences of non-adherence to CPMM, interventions are needed to improve medication non-adherence. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), possible targets for these interventions can be divided into five domains:Citation2 socio-economic factors, health care system factors, condition-related factors, therapy-related factors, and patient-related factors. Although none of the factors within these domains are consistently associated with non-adherence across conditions, some tend to be better predictors of non-adherence than others (like poverty, the nature of the disease, and side-effects).Citation1,Citation2 Also, psychosocial factors like beliefs about medication, self-efficacy, and social support can be promising intervention targets. These are mostly modifiable (in contrast to factors like poverty or side-effects), and according to reviews of cross-sectional studies, they appear to be associated with non-adherence in various somatic, chronic conditions.Citation6–Citation13 Beliefs about medication were the most powerful predictors of adherence (among demographic and medical factors) in one cross-sectional study,Citation9 while another cross-sectional study identified low-self-efficacy as a significant predictor of non-adherence across different countries, for example.Citation11 However, there is no insight into psychosocial factors predicting non-adherence in longitudinal studies with a longer follow-up period (≥3 months). Such knowledge would be helpful in designing effective adherence interventions in clinical practice.

This is the first review which aims to systematically synthesize evidence of longitudinal associations between psychosocial predictors and CPMM non-adherence across adult patients living in Western countries. Since non- adherence literature is scattered across diseases,Citation14 we combined studies from various somatic, chronic conditions to increase the robustness of our findings.

Methods

PRISMA-guidelines were followed in performing this systematic review.Citation15 The steps taken regarding data searches, study selection, data extraction, study quality assessment, data synthesis, and data analyses are elaborated below.

Data sources and searches

In March 2011, according to a pre-defined search strategy, four electronic databases (PUBMED, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsychINFO) were searched for studies up to February 2011. With this search, a first set of studies was included, the reference lists of these studies were hand searched to find additional studies. The studies were also entered into the ISI Web of Knowledge citation index (August 2011). The resulting list of studies, citing one of the initial included studies in our review, was also searched.

The search strategy (see Supplementary Materials) contains key words on medication adherence, chronic, somatic diseases, adults, longitudinal designs, and Western countries. Countries in Africa, Latin-America, South-America, Asia (excluding Indonesia and Japan), and Turkey were considered as non-Western according to Statistics Netherlands.Citation16 Non-Western countries were excluded because underlying mechanisms of medication non-adherence could differ from those in Western countries due to socio-economic and cultural differences.Citation17

In this review, we focused on two of the three components of adherence (ie, on initiation and implementation adherence, thus the extent to which a patient’s actual medication dosing regimen corresponds with the prescribed dosing regimen from initiation to last dose). We did not include discontinuation of medication.Citation1

As using CPMM terms in the search strategy was unfeasible, we used the corresponding diseases for which the CPMMs were prescribed as search terms instead. The disease terms were selected as follows:

Chronic preventive maintenance medications were defined. CPMMs were regarded as drugs that 1) are intended to be used chronically to prevent the occurrence or worsening of a disease or its complications; and 2) may have an immediate effect, but must also have a long-term effect (>3 months).

From the full November 2010 Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (ATC)-7 medication list of drugs available in the Netherlands, 246 CPMMs (Supplementary Materials) were independently selected by two pharmacists (BvdB and VH). There was an initial agreement of 96% on medications being CPMM. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the pharmacists.

Disease indications for the 246 CPMMs were subsequently clustered by BvdB according to the International Classification of Diseases (WHO). Finally, 20 disease terms were used in the search strategy.

Study selection

Studies were selected based on the criteria in .

Table 1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies exclusively recruiting subpopulations in special conditions (like prisoners, pregnant women) were excluded. Their results only pertain to a specific group of patients, therefore, including them might have introduced bias into this systematic review.

Two reviewers (BvdB and HZ) independently assessed studies for eligibility in two phases: 1) screening based on title and abstract; and 2) screening based on full text. Disagreements between BvdB and HZ were resolved by discussion; a third reviewer (CvdE) made decisions in case disagreements could not be resolved. Studies in Spanish or Portuguese were judged by LvdA. During the study selection process, three authors were contacted about statistics, outcome measure, or study design to determine eligibility for this review.Citation20–Citation22

Data extraction and quality assessment

For data extraction, a literature-based, standard form was developed.Citation23,Citation24 Information regarding study setting, design, descriptive statistics, measures, and analysis were extracted by HZ; BvdB arbitrarily selected 15% of the included studies to check appropriateness of all extracted data of these studies, and also checked all doubts indicated on the form by HZ.

If multiple adherence measures were presented in one study (eg, about dosing, timing, or taking medication)Citation25, we only extracted data about taking medication. Two authors were contacted during the extraction process to check the duration of a follow-up period of ≥3 monthsCitation26 or to explain ambiguities.Citation19

We adapted the framework developed by Hayden et alCitation27 to judge methodologic study quality. Our framework contained 23 items divided into six bias domains: study participation, study attrition, prognostic, outcome and confounding measurement, and analyses. Each item was scored as ‘yes’ (no unacceptable amount of bias introduced), ‘partly’ (/unsure), and ‘no’ (unacceptable amount of bias introduced). For every bias domain, a transparent method was used to reach overall judgment about the presence or absence of bias (see ). Studies with ≥four domains judged as ‘yes’ were considered high-quality studies; studies with <four domains were considered low-quality studies.

Using three randomly selected studies not included in the review, the framework was piloted by BvdB and HZ, who also performed the actual quality assessment. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and, when necessary, a third reviewer (CvdE) made final decisions. On the domain level, a weighted extent of agreement between BvdB and HZ (quadratic weighting scheme) was calculated due to the ordinal nature of the scores.Citation28,Citation29

Data synthesis and analysis

Because over 70 non-identical psychosocial predictors (non-identical by name and/or measurement instrument) were studied in this review, and because of the variety of instruments used to measure non-adherence, a qualitative instead of a quantitative analysis was considered to be appropriate.Citation30 Therefore, the results regarding associations between psychosocial predictors and medication non-adherence were qualitatively synthesized in four steps.

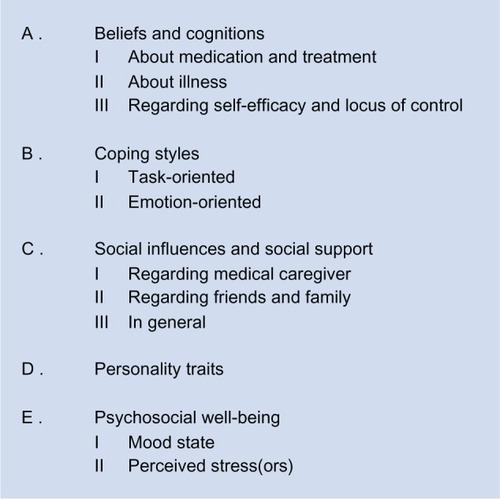

In step 1, psychosocial categories were formulated. Initially, all psychosocial elements as mentioned in general health behavior models and theoriesCitation31,Citation32 were listed (HZ). Subsequently, based on consensus, the elements were clustered by HZ and three psychologists (SvD, JV, and LK) resulting in the categories of .

Next, the psychosocial predictors within the studies of the review were assigned to one of the categories in (HZ and the psychologists). In this way, the considerable number of single, non-identical predictors was dealt with.

In step 2, for each psychosocial predictor within a category and within a study, the presence of a significant univariate and multivariate association with medication non-adherence was determined (see ). Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

In step 3, results within studies were synthesized per psychosocial category. When ≥75% of variables within a single psychosocial category were significantly and consistently (ie, same predictors in same direction) associated with non-adherence, a ‘yes’ was assigned (ie, association present). When ≥75% of variables were significantly, but inconsistently, associated (eg, four of five predictors in category about depressive symptoms, of which two are positively related to non-adherence and two are negatively related), the term ‘conflicting’ was assigned. When <75% of variables were significantly and consistently associated, a ‘no’ was assigned. Multivariate results were preferably used to synthesize results in this step. When multivariate results were not reported, univariate results were used.

In the fourth and final step, a best evidence synthesis (BES) per psychosocial category between studies was performed to summarize evidence of longitudinal associations between the predictors in the psychosocial categories and medication non-adherence. We defined four levels of evidence as used in previous reviews of longitudinal studies:Citation60 –Citation62

Strong evidence: consistent findings (≥75% of studies within psychosocial category report same conclusion about association; ie, ‘yes, present’ or ‘no, not present’) in at least two high-quality studies.

Moderate evidence: consistent findings in one high-quality study AND at least two low-quality studies.

Limited evidence: findings in one high-quality study OR consistent findings in at least two low-quality studies.

Conflicting evidence: inconsistent findings in at least two studies irrespective of study quality (ie, <75% of studies report same conclusion about association). Note that this level of evidence was checked first before assigning strong, moderate or limited evidence level to a category.

The level of evidence was undeterminable when ≤one study of low quality was available for a psychosocial category.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to examine the robustness of findings, regarding the cut-off point for methodological quality, diseases, adherence measurement, and statistical analyses (ie, focusing on univariate analyses only). Also, an additional analysis on single predictors was carried out, since associations between single predictors like ‘avoidance coping’ and non-adherence could be overshadowed by combining them into a single category with generally non-significant psychosocial predictors, such as hopelessness and confusion. Three steps were taken: 1) all significant predictors (P≤0.05) were listed; 2) each of these predictors was grouped with identically named, significant and non-significant predictors; and 3) when at least two studies were available for those predictors, the BES rules were applied.

Results

Study inclusion

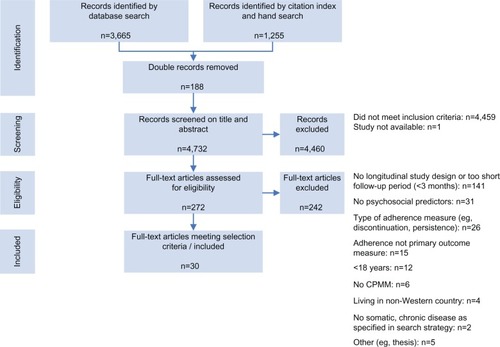

Of 4,732 non-duplicate references, 30 met our inclusion criteria ().Citation19,Citation25,Citation26,Citation33–Citation59 In all, 1,255 records were identified by screening the reference lists and the ISI Web of Knowledge citation index of the initial included studies.

Figure 2 Flowchart of study inclusion process.

Initially, the percentage of agreement regarding the eligibility of studies was 86% (of the 272 studies selected on title and abstract, agreement was obtained in about 235 studies after reading the full-text). Disagreements were mainly due to misconceptions about psychosocial predictors (eg, clinically diagnosed depression versus symptoms of depression), study design, and adherence measure (ie, discontinuation or execution adherence). For one study,Citation52 disagreement could not be resolved by discussion and thus a final decision was made by CvdE.

Study characteristics and quality assessment

displays study characteristics, measures, and results. A comprehensive table of measures and results is presented in .

Table 2 Study characteristics and resultsTable Footnote*

The included studies (all based on different data sets) covered CPMMs for asthma, diabetes, heart diseases/hypertension, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and organ transplants. Medication type was not explicitly mentioned in four studies,Citation37,Citation38,Citation45,Citation59 but we assumed CPMM was used since CPMM is the standard medical treatment for the 20 selected diseases in this review. In most studies, patients were recruited from medical clinics or hospitals and the sample size ranged from 50–1,911. Attrition rates varied from 0%–71%. Participants were predominantly men and often ≥37 years of age and a disease duration of >2 years. The observation period between baseline and last adherence measurement was ≥3 and <12 months in ten studies and ≥12 months in 20 studies, with a maximum of 60 months. Medication adherence was mostly measured by self-report (18 studies, predominantly questionnaires); seven studies used a validated adherence questionnaire.Citation33,Citation36,Citation43,Citation46,Citation49–Citation51 Other adherence measurements were carried out by reviewing medical records or the medication event monitoring system (MEMS). In 15 studies, both univariate and multivariate analyses were reported.

All 30 included studies were judged to be ‘low-quality’ (). This was mainly due to poor descriptions and/or bias regarding the study sample, the use of non-validated questionnaires, the lack of accounting for confounding variables, and a poor description of the data analyses. Most studies, moreover, did not appropriately describe actions taken in case of missing data.

A total of 180 bias domains were judged (30 studies by six domains). Initially, BvdB and HZ fully agreed on 78 domains, partially agreed (ie, ‘partly’ versus ‘no’ or ‘partly’ versus ‘yes’) on 79 domains and fully disagreed (eg, ‘yes’ versus ‘no’) on 23 domains, resulting in a weighted agreement of 76%. Disagreements were caused by poor description of methods, different interpretations of missing data, differences in calculating study attrition rates, and different interpretations regarding the appropriateness of study sample descriptions. On this latter point, disagreements about three studiesCitation35,Citation48,Citation52 could not be resolved by discussion between BvdB and HZ and, thus, CvdE made the final decision.

Best evidence synthesis

shows there is limited evidence for the absence of a longitudinal association with medication non-adherence in all of the eleven psychosocial subcategories.

Table 3 Level of evidence for longitudinal associations between psychosocial categories and medication non-adherence

Beliefs and cognitions

Regarding category AI (beliefs and cognitions about medication and treatment), two of nine studies found a longitudinal, multivariate association between having a positive attitude towards taking medication and adherence (odds ratio [OR] =1.56, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.18, 2.06),Citation43 and between necessity beliefs and concern beliefs about medication and adherence (OR =2.19, 95% CI 1.02, 4.71 and OR =0.45, 95% CI 0.22, 0.96, respectively).Citation49 One other studyCitation33 found univariate associations between necessity and concern beliefs about medication and adherence, but these associations did not hold in the multivariate analysis.

One study demonstrated a longitudinal, multivariate association between low self-efficacy and medication non-adherence;Citation53 however, the effect size was small. Univariate, but not multivariate associations between self-efficacy and adherence were demonstrated in two studies.Citation55,Citation57

Coping styles

No univariate and multivariate associations were found between the task-oriented coping style category and medication adherence.

Regarding emotion-oriented coping styles, one of six studies revealed a multivariate association with non-adherence (eg, OR of 9.71 for avoidance coping).Citation56 Furthermore, avoidance coping as a single predictor was associated with non-adherence in three of four studies measuring this construct.Citation25,Citation40,Citation56

Social influences and social support

Two of the 25 studies demonstrated significant associations between predictors within the category social influences and social support and (non-)adherence, but only one of these studies reported on a multivariate association between having support from a partner and non-adherence (regression coefficient =−0.15, 95% CI −0.25, −0.05).Citation51 Receiving practical social support was associated with better adherence as a single predictor.Citation38,Citation41

Personality traits

One of eight studies showed a multivariate, longitudinal association between the category of personality traits and medication non-adherence:Citation26 a lower sense of coherence (a global life orientation in which life is perceived as comprehensible, manageable and meaningful)Citation63 was associated with greater non-adherence (OR=0.55, CI 0.31–0.96). Associations between other predictors within the personality traits category and non-adherence were lacking.

Psychological well-being

Regarding categories EI (mood state) and EII (perceived stress/stressors), no associations between predictors in those categories and medication non-adherence could be established for the vast majority of studies (24 out of 29). Two of the five studies which did show significant associations reported on multivariate analyses: the regression coefficient for depressive symptoms was 0.18 (95% CI 0.07, 0.29) in predicting non-adherence;Citation51 the standardized beta for health distress was −0.22 (CI not reported) for predicting adherence.Citation59

can be consulted for detailed information about associations between single psychosocial predictors and medication adherence/non-adherence.

Sensitivity analyses

The sensitivity analyses confirmed that, generally, no association was found between the psychosocial categories and medication non-adherence ().

The additional analysis on single predictors showed no association between most single, psychosocial predictors and medication non-adherence. However, conflicting evidence was found for having a positive attitude towards taking medication,Citation37,Citation43 necessity beliefs and concern beliefs about medication,Citation33,Citation49 self-efficacy in medication-taking,Citation25,Citation33,Citation43,Citation47,Citation53,Citation54 the coping style “planful problem solving”,Citation25,Citation41 and (the number of) stressful (life) events.Citation38,Citation42,Citation46 Limited evidence was found for an association between escape-avoidance coping and medication non-adherence,Citation25,Citation41,Citation56,Citation59 and for an association between receiving practical, social support and medication adherence.Citation38,Citation41

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review summarizing evidence of longitudinal associations between psychosocial factors and non-adherence to CPMM, irrespective of somatic disease. Due to the low quality of the included studies, limited evidence was found for absence of longitudinal associations between categories of psychosocial predictors and medication non-adherence. In general, findings were robust according to sensitivity analyses.

Our findings of longitudinal associations between psychosocial factors and medication non-adherence are in line with the few conducted cross-sectional studies about associations between medication adherence, coping styles, personality traits, and psychosocial well-being (except depressive symptoms) in somatic conditions. The findings in these cross-sectional studies are ambiguous at best.Citation8,Citation64–Citation68 For example, an active coping style was associated with medication adherence in some studiesCitation8,Citation68 but not in others,Citation64,Citation66 and stress was associated with lesser adherence in a study of Holt et al,Citation67 but was unrelated to non-adherence in a study of Ediger et al.Citation65

In contrast to coping styles and personality traits, depression is often studied as possible predictor of medication non-adherence. Here, our results are not in line with results from other reviews, reporting depression to be a predictor of medication non-adherence.Citation6,Citation69–Citation74 Initially, this discrepancy might be explained by the fact that clinical depression is within the scope of most other studies, but beyond the scope of our systematic review since we did not study morbidity as a predictor of non-adherence; instead, we studied depressive symptoms. Second, an explanation might be that those other reviews included studies with mainly cross-sectional designs. Feelings of depression might increase and decrease over the course of a disease. A high degree of depressive feelings might correlate well with non-adherent behavior at that same time, but just might not be predictive of non-adherent behavior in the future due to this changeability. Thus, longitudinal associations between depressive feelings and non-adherence might not be applicable.

This thought might also apply to discrepancies in findings between our review and other reviews on associations between beliefs about medication/treatment, poor social support, and non-adherence. These other reviews underline the importance of beliefs about medication/treatment and poor social support in predicting medication non-adherenceCitation6,Citation10,Citation69–Citation76 in contrast to our review findings, but again, those other reviews are mainly based on studies with cross-sectional designs.

In terms of internal validity, a strength of this review is that we, in contrast to others, systematically defined and categorized psychosocial factors. By doing so, we were able to 1) draw a concise number of conclusions about associations between psychosocial predictors and medication non-adherence in a reproducible manner; 2) address the heterogeneity between single, psychosocial predictors; and 3) address an important goal of a systematic review: converging information. The pitfall of categorization (eg, the possibility of overlooking significant associations between certain, single predictors and non-adherence, by pooling them with other types of [non-significant] predictors), was avoided by performing an extended sensitivity analysis on single predictors. This analysis revealed our conclusions to be robust for almost all single, psychosocial predictors included in this review.

Another strength of this review is that we systematically synthesized results using a best evidence synthesis in contrast to most other reviews, which tend to be characterized by narrative designs.Citation6,Citation10,Citation69,Citation70,Citation73,Citation74,Citation76 Narrative designs often do not rely on systematic methods to assign weight of evidence; eg, by incorporating methodological quality of included studies.Citation77 Although no review procedure eliminates the chance that reviewers’ biases will affect the conclusions drawn,Citation77 the application of a best evidence synthesis makes a review procedure transparent and reproducible.

A limitation of this systematic review is that we used chronic disease terms instead of medication terms in the search strategy and, consequently, we may have missed relevant studies about chronic preventive maintenance medication. However, we assume that the number of missed studies is minimal, since diseases are usually mentioned in medication adherence studies.

Another limitation could be the use of results of univariate analyses to draw conclusions about associations in the absence of multivariate analysis data, as univariate analyses could lead to an overestimating of the strength of associations. However, our sensitivity analyses on data from univariate analyses confirmed the robustness of our findings.

Concerning external validity, a strong feature of this review is that it focused exclusively on longitudinal associations between psychosocial predictors and medication non-adherence, thereby providing insight into the temporality and robustness of associations. However, only 5 of the 30 studies included in our review corrected for baseline non-adherence.Citation34,Citation50,Citation53,Citation58,Citation59 Failure to account for baseline non-adherence when suggesting predictive longitudinal associations is considered a liberal approach,Citation78 since baseline non-adherence is likely to explain a substantial part of the variance in non-adherence over time. Because we did not find any associations using a liberal approach, however, we believe it is unlikely that handling a strict longitudinal approach in this review would have altered our findings.

Another limitation concerning external validity is that the poor quality of the included studies prevented us from drawing firm conclusions about the lack of associations between psychosocial predictors and medication adherence The lack of a gold standard for adherence measurementCitation73 also restricts the validity of our findings. The adherence measures used in the included studies of this review (self-report, refill data, and electronic monitoring) do not measure actual ingestion, and the use of self-report and electronic monitoring might have introduced response bias because of participants’ awareness of the measurements. However, all medication adherence related research has to deal with the limitations of adherence measurements. For now, our review provides the best evidence currently available, and clearly demonstrates the need for more high-quality, longitudinal research into associations between psychosocial predictors and medication non-adherence.

Two recommendations for future research can be made. First, future longitudinal research into psychosocial predictors of medication non-adherence should be of high quality. Researchers should, for example, use valid measures of psychosocial predictors and medication non-adherence and should thoroughly describe which steps were performed in the study, especially those relating to handling missing data and avoiding bias.

Second, the research gap in longitudinal studies into associations between psychosocial predictors and medication non- adherence in patients with conditions such as rheumatic diseases, migraine disorders, gout, glaucoma, and stomach ulcers (see Supplementary Materials) should be complemented. Although we assume that review findings will also apply to these diseases, this assumption needs to be confirmed.

The conclusion of this systematic review is that there is limited evidence for absence of longitudinal associations between psychosocial predictors and medication non-adherence. Consequently, our results do not provide psychosocial targets for the development of new interventions in clinical practice. However, the usefulness of psychosocial predictors in improving medication adherence should not be ruled out, as more high-quality research is needed to confirm or refute the conclusion of this review. Such future research could also further explore the associations found in this review between escape-avoidance coping and medication non-adherence, and between receiving practical, social support and medication adherence.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Linda Kwakkenbos for her contribution in defining the psychosocial categories, Lieke van der Aa for translating studies of the Spanish/Portuguese language and Victor Huiskes for selecting chronic preventive maintenance medication.

Supplementary materials

Pubmed search strategy

(((adult[MeSH Terms] OR mature[tw] OR adult[tw])

AND

((Ischaemic heart diseases[TW] OR angina pectoris[TW] OR Myocardial Ischemia[TW] OR asthma[TW] OR Diabetes mellitus[TW] OR diabetes mellitus[TW] OR hypercholesterolaemia[TW] OR hyperlipidaemia[TW] OR Dyslipidemias[TW] OR Gastric ulcer[TW] OR Duodenal ulcer[TW] OR Stomach Ulcer[TW] OR glaucoma[TW] OR glaucoma[TW] OR heart failure[TW] OR Heart failure[TW] OR arrhythmias[TW] OR Arrhythmias, Cardiac[TW] OR “Human immunodeficiency virus” OR HIV disease[TW] OR HIV-disease[TW] OR HIV infections[TW] OR HIV-infections[TW] OR Hypertensive diseases[TW] OR Hypertension[TW] OR Ulcerative colitis[TW] OR Crohn’s disease[TW] OR Inflammatory Bowel Diseases[TW] OR Arthropathies[TW] OR gout[TW] OR Malignant neoplasm of breast[TW] OR Breast Neoplasms[TW] OR Hereditary angioedema[TW] OR Angioedemas, Hereditary[TW] OR transplantation[TW] OR Organ Transplantation[TW] OR migraine[TW] OR Migraine Disorders[TW] OR osteoporosis[TW] OR arthropathy[TW] OR Systemic connective tissue disorders[TW] OR psoriatic arthropathy[TW] OR rheumatoid arthritis[TW] OR Systemic lupus erythematosus[TW] OR Systemic sclerosis[TW] OR Arthritis, Psoriatic[TW] OR Arthritis, Rheumatoid[TW] OR Lupus Erythematosus, Systemic[TW] OR Scleroderma, Systemic[TW] OR Arterial embolism[TW] OR thrombosis[TW] OR venous embolism[TW] OR Embolism and Thrombosis[TW] OR Paget Disease[TW] OR Osteitis Deformans[TW]) OR (Myocardial Ischemia[MH] OR asthma[MH] OR diabetes mellitus[MH] OR Dyslipidemias[MH] OR Stomach Ulcer[MH] OR glaucoma[MH] OR Heart failure[MH] OR Arrhythmias, Cardiac[MH] OR HIV infections[MH] OR Hypertension[MH] OR Inflammatory Bowel Diseases[MH] OR gout[MH] OR Breast Neoplasms[MH] OR Angioedemas, Hereditary[MH] OR Organ Transplantation[MH] OR Migraine Disorders[MH] OR osteoporosis[MH] OR Arthritis, Psoriatic[MH] OR Arthritis, Rheumatoid[MH] OR Lupus Erythematosus, Systemic[MH] OR Scleroderma, Systemic[MH] OR Embolism and Thrombosis[MH] OR Osteitis Deformans[MH]))

AND

((medication adherence[MH] OR patient compliance[MH]) OR (medication compliance[TW] OR medication noncompliance[TW] OR medication non compliance[TW] OR medication noncompliance[TW] OR medication adherence[TW] OR medication non-adherence[TW] OR medication non adherence[TW] OR medication nonadherence[TW] OR medication adherance[TW] OR medication non-adherance[TW] OR medication non adherance[TW] OR medication nonadherance[TW] OR medication persistence[TW] OR medication non-persistence[TW] OR medication non persistence[TW] OR medication nonpersistence[TW] OR medication persistance[TW] OR medication non-persistance[TW] OR medication non persistance[TW] OR medication nonpersistance[TW] OR medicine compliance[TW] OR medicine non-compliance[TW] OR medicine non compliance[TW] OR medicine noncompliance[TW] OR medicine adherence[TW] OR medicine non-adherence[TW] OR medicine non adherence[TW] OR medicine nonadherence[TW] OR medicine adherance[TW] OR medicine non-adherance[TW] OR medicine non adherance[TW] OR medicine nonadherance[TW] OR medicine persistence[TW] OR medicine non-persistence[TW] OR medicine non persistence[TW] OR medicine nonpersistence[TW] OR medicine persistance[TW] OR medicine non-persistance[TW] OR medicine non persistance[TW] OR medicine nonpersistance[TW] OR medical compliance[TW] OR medical non-compliance[TW] OR medical non compliance[TW] OR medical noncompliance[TW] OR medical adherence[TW] OR medical non-adherence[TW] OR medical non adherence[TW] OR medical nonadherence[TW] OR medical adherance[TW] OR medical non-adherance[TW] OR medical non adherance[TW] OR medical nonadherance[TW] OR medical persistence[TW] OR medical non-persistence[TW] OR medical non persistence[TW] OR medical nonpersistence[TW] OR medical persistance[TW] OR medical non-persistance[TW] OR medical non persistance[TW] OR medical nonpersistance[TW] OR drug compliance[TW] OR drug non-compliance[TW] OR drug non compliance[TW] OR drug noncompliance[TW] OR drug adherence[TW] OR drug non-adherence[TW] OR drug non adherence[TW] OR drug nonadherence[TW] OR drug adherance[TW] OR drug non-adherance[TW] OR drug non adherance[TW] OR drug nonadherance[TW] OR drug persistence[TW] OR drug non-persistence[TW] OR drug non persistence[TW] OR drug nonpersistence[TW] OR drug persistance[TW] OR drug non-persistance[TW] OR drug non persistance[TW] OR drug nonpersistance[TW] OR drugs compliance[TW] OR drugs non-compliance[TW] OR drugs non compliance[TW] OR drugs noncompliance[TW] OR drugs adherence[TW] OR drugs non-adherence[TW] OR drugs non adherence[TW] OR drugs nonadherence[TW] OR drugs adherance[TW] OR drugs non-adherance[TW] OR drugs non adherance[TW] OR drugs nonadherance[TW] OR drugs persistence[TW] OR drugs non-persistence[TW] OR drugs non persistence[TW] OR drugs nonpersistence[TW] OR drugs persistance[TW] OR drugs non-persistance[TW] OR drugs non persistance[TW] OR drugs nonpersistance[TW]))

AND

(Prospective Studies[MH] OR Longitudinal Studies[MH] OR Cohort Studies[MH] OR Follow-up Studies[MH] OR Retrospective Studies[MH] OR Prospective Studies[TIAB] OR Longitudinal Studies[TIAB] OR Cohort Studies[TIAB] OR Follow-up Studies[TIAB] OR Retrospective Studies[TIAB] OR observational stud*[TIAB] OR predict*[TW] OR prognos*[TW] OR prognostic factor*[TW] OR course[TW] OR determinant*[TW]))

NOT

“Africa”[Mesh] OR “Latin America”[Mesh] OR “Asia, Central”[Mesh] OR “Borneo”[Mesh] OR “Brunei”[Mesh] OR “Cambodia”[Mesh] OR “East Timor”[Mesh] OR “Laos”[Mesh] OR “Malaysia”[Mesh] OR “Mekong Valley”[Mesh] OR “Myanmar”[Mesh] OR “Philippines”[Mesh] OR “Singapore”[Mesh] OR “Thailand”[Mesh] OR “Vietnam”[Mesh] OR “Bangladesh”[Mesh] OR “Bhutan”[Mesh] OR “India”[Mesh] OR “Afghanistan”[Mesh] OR “Bahrain”[Mesh] OR “Iran”[Mesh] OR “Egypt”[Mesh] OR “Iraq”[Mesh] OR “Israel”[Mesh] OR “Jordan”[Mesh] OR “Kuwait”[Mesh] OR “Lebanon”[Mesh] OR “Oman”[Mesh] OR “Qatar”[Mesh] OR “Saudi Arabia”[Mesh] OR “Syria”[Mesh] OR “United Arab Emirates”[Mesh] OR “Yemen”[Mesh] OR “Nepal”[Mesh] OR “Pakistan”[Mesh] OR “Sri Lanka”[Mesh] OR “China”[Mesh] OR “Korea”[Mesh] OR “Mongolia”[Mesh] OR “Taiwan”[Mesh]

NOT

(youth[TIAB] OR child*[TIAB])

NOT

(Clinical Trial[MH] OR case reports[PT] OR review[PT] OR meta-analysis[MH] OR Cross-sectional Studies[MH] OR Case-control Studies[MesH:NoExp] OR Clinical Trial*[PT] OR case report*[PT] OR review*[PT] OR meta-analys*[PT] OR case report*[TIAB] OR case-report*[TIAB] OR review*[TIAB] OR systematic review*[TIAB] OR meta-analys*[TIAB] OR randomized controlled trial*[TIAB] OR randomised controlled trial*[TIAB] OR clinical trial*[TIAB] OR controlled clinical trial*[TIAB] OR cross-sectional*[TIAB] OR cross sectional*[TIAB] OR Case-control Studies[TIAB] OR case-control[TIAB] OR case control[TIAB] OR Editorial[ptyp] OR Letter[ptyp] OR Comment[ptyp] OR Interview[ptyp] OR Newspaper Article[ptyp])

Chronic preventive maintenance medication

Table S1 Framework for judging methodological quality

Table S2 explanation of measures and resultsTable Footnote*

Table S3 Results of judging methodologic quality

Table S4 Sensitivity analyses: methodological quality, disease, adherence measures, and statistical analyses

References

- PoniemanDWisniveskyJPLeventhalHMusumeci-SzabóTJHalmEAImpact of positive and negative beliefs about inhaled corticosteroids on adherence in inner-city asthmatic patientsAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol20091031384219663125

- VenturiniFNicholMBSungJCBaileyKLCodyMMcCombsJSCompliance with sulfonylureas in a health maintenance organization: a pharmacy record-based studyAnn Pharmacother199933328128810200850

- GazmararianJAKripalaniSMillerMJEchtKVRenJRaskKFactors associated with medication refill adherence in cardiovascular-related diseases: a focus on health literacyJ Gen Intern Med200621121215122117105519

- NabiHVahteraJSingh-ManouxADo psychological attributes matter for adherence to antihypertensive medication? The Finnish Public Sector Cohort StudyJ Hypertens200826112236224318854766

- GrégoireJMoisanJGuibertRCiampiAMilotAPredictors of self-reported noncompliance with antihypertensive drug treatment: a prospective cohort studyCan J Cardiol200622432332916568157

- MillerPWikoffRLMcMahonMGarrettMJRingelKIndicators of medical regimen adherence for myocardial infarction patientsNurs Res19853452682723850486

- MolloyGJPerkins-PorrasLBhattacharyyaMRStrikePCSteptoeAPractical support predicts medication adherence and attendance at cardiac rehabilitation following acute coronary syndromeJ Psychosom Res200865658158619027448

- DeschampsAEGraeveVDvan WijngaerdenEPrevalence and correlates of nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy in a population of HIV patients using Medication Event Monitoring SystemAIDS Patient Care STDS2004181164465715633262

- HolmesWCBilkerWBWangHChapmanJGrossRHIV/AIDS-specific quality of life and adherence to antiretroviral therapy over timeJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200746332332717846560

- DelgadoJHeathKVYipBHighly active antiretroviral therapy: physician experience and enhanced adherence to prescription refillAntivir Ther20038547147814640395

- SinghNSquierCSivekCWagenerMNguyenMHYuVLDeterminants of compliance with antiretroviral therapy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus: prospective assessment with implications for enhancing complianceAIDS Care1996832612698827119

- SinghNBermanSMSwindellsSAdherence of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients to antiretroviral therapyClin Infect Dis199929482483010589897

- BottonariKARobertsJECieslaJAHewittRGLife stress and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive individuals: a preliminary investigationAIDS Patient Care STDS2005191171972716283832

- GodinGCôtéJNaccacheHLambertLDTrottierSPrediction of adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a one-year longitudinal studyAIDS Care200517449350416036235

- KacanekDJacobsonDLSpiegelmanDWankeCIsaacRWilsonIBIncident depression symptoms are associated with poorer HAART adherence: a longitudinal analysis from the Nutrition for Healthy Living studyJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr201053226627220104122

- MartiniMD’EliaSPaolettiFAdherence to HIV treatment: results from a 1-year follow-up studyHIV Med200231626412059953

- MellinsCAKangELeuCSHavensJFChesneyMALongitudinal study of mental health and psychosocial predictors of medical treatment adherence in mothers living with HIV diseaseAIDS Patient Care STDS200317840741613678542

- Nilsson SchönnessonLDiamondPMRossMWWilliamsMBrattGBaseline predictors of three types of antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence: A 2-year follow-upAIDS Care200618440741416809121

- ThrasherADEarpJAGolinCEZimmerCRDiscrimination, distrust, and racial/ethnic disparities in antiretroviral therapy adherence among a national sample of HIV-infected patientsJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr2008491849318667919

- HorneRCooperVGellaitryGDateHLFisherMPatients’ perceptions of highly active antiretroviral therapy in relation to treatment uptake and adherence: the utility of the necessity-concerns frameworkJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200745333434117514019

- MugaveroMJRaperJLReifSOverload: impact of incident stressful events on antiretroviral medication adherence and virologic failure in a longitudinal, multisite human immunodeficiency virus cohort studyPsychosom Med200971992092619875634

- CarrieriMPLeportCProtopopescuCFactors associated with nonadherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: a 5-year follow-up analysis with correction for the bias induced by missing data in the treatment maintenance phaseJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200641447748516652057

- StilleyCSDiMartiniAFde VeraMEIndividual and environmental correlates and predictors of early adherence and outcomes after liver transplantationProg Transplant20102015866 quiz 6720397348

- De GeestSAbrahamIMoonsPLate acute rejection and subclinical noncompliance with cyclosporine therapy in heart transplant recipientsJ Heart Lung Transplant19981798548639773856

- RussellCLCetingokMHamburgerKQMedication adherence in older renal transplant recipientsClin Nurs Res20101929511220185804

- WengFLIsraniAKJoffeMMRace and electronically measured adherence to immunosuppressive medications after deceased donor renal transplantationJ Am Soc Nephrol20051661839184815800121

- DewMARothLHThompsonMEKormosRLGriffithBPMedical compliance and its predictors in the first year after heart transplantationJ Heart Lung Transplant19961566316458794030

- DewMADimartiniAFDe VitoDabbsAAdherence to the medical regimen during the first two years after lung transplantationTransplantation200885219320218212623

- DobbelsFVanhaeckeJDupontLPretransplant predictors of posttransplant adherence and clinical outcome: an evidence base for pretransplant psychosocial screeningTransplantation200987101497150419461486

- DiMatteoMRSherbourneCDHaysRDPhysicians’ characteristics influence patients’ adherence to medical treatment: results from the Medical Outcomes StudyHealth Psychol1993122931028500445

- PearlinLILiebermanMAMenaghanEGMullanJTThe stress processJ Health Soc Behav19812243373567320473

- BerkmanLFLeo-SummersLHorwitzRIEmotional support and survival after myocardial infarction. A prospective, population-based study of the elderlyAnn Intern Med199211712100310091443968

- SeemanTEBerkmanLFStructural characteristics of social networks and their relationship with social support in the elderly: who provides supportSoc Sci Med19882677377493358145

- ChesneyMAIckovicsJRChambersDBSelf-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. Patient Care Committee and Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG)AIDS Care200012325526610928201

- SpanierGBMeasuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyadsJ Marriage Fam19763811528

- PearlinLISchoolerCThe structure of copingJ Health Soc Behav1978191221649936

- MoosRHEvaluating correctional and community settingsAhmedICoelhoGVToward a New Definition of Health: Psychosocial DimensionsNew YorkPlenum Press1979337360

- SherbourneCDHaysRDOrdwayLDiMatteoMRKravitzRLAntecedents of adherence to medical recommendations: results from the Medical Outcomes StudyJ Behav Med19921554474681447757

- SherbourneCDStewartALThe MOS social support surveySoc Sci Med19913267057142035047

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ABC project teamAscertaining barriers for compliance: policies for save, effective and cost-effective use of medicines in Europe. Final report of the ABC-ProjectLodz, PolandABC Project2012 Available from: http://abcproject.eu/index.php?page=publicationsAccessed September 14, 2012

- World Health OrganizationAdherence to long-term therapies. Evidence for actionGenevaWorld Health Organization2003 Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241545992.pdfAccessed August 1, 2012

- van DulmenSSluijsEvan DijkLde RidderDHeerdinkRBensingJPatient adherence to medical treatment: a review of reviewsBMC Health Serv Res200775517439645

- PsatyBMKoepsellTDWagnerEHLoGerfoJPInuiTSThe relative risk of incident coronary heart disease associated with recently stopping the use of beta-blockersJAMA199026312165316571968518

- BalkrishnanRChristensenDBInhaled corticosteroid use and associated outcomes in elderly patients with moderate to severe chronic pulmonary diseaseClin Ther200022445246910823366

- ElliottRAPoor adherence to medication in adults with rheumatoid arthritis: reasons and solutionsDis Manag Health Outcome20081611329

- GauchetATarquinioCFischerGPsychosocial predictors of medication adherence among persons living with HIVInt J Behav Med200714314115018062057

- GremigniPBacchiFTurriniCCappelliGAlbertazziABittiPEPsychological factors associated with medication adherence following renal transplantationClin Transplant200721671071517988263

- HorneRWeinmanJPatients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illnessJ Psychosom Res199947655556710661603

- KaneSVRobinsonAReview article: understanding adherence to medication in ulcerative colitis – innovative thinking and evolving conceptsAliment Pharmacol Ther20103291051105820815833

- MorrisonVFargherEParveenSDeterminants of Patient Adherence to Antihypertensive Medication: A Multi-national Cross-sectional StudyLodz, PolandABC Project2012 Available from: http://abcproject.eu/index.php?page=publicationsAccessed July 10, 2013

- OsterbergLBlaschkeTAdherence to medicationN Engl J Med2005353548749716079372

- UnniEFarrisKBDeterminants of different types of medication non-adherence in cholesterol lowering and asthma maintenance medications: a theoretical approachPatient Educ Couns201183338239021454030

- HaynesRBAcklooESahotaNMcDonaldHPYaoXInterventions for enhancing medication adherence [review]Cochrane Database Syst Rev20082CD00001118425859

- LiberatiAAltmanDGTetzlaffJThe PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaborationBMJ2009339b270019622552

- http://www.cbs.nl [homepage on the Internet]Definitions. Someone with a Western backgroundCentraal Bureau voor de Statistiek2012 Available from: http://www.cbs.nl/en-GB/menu/methoden/begrippen/default.htm?Languageswitch=on&ConceptID=1057Accessed November 11, 2012

- OsamorPEOwumiBEFactors associated with treatment compliance in hypertension in southwest NigeriaJ Health Popul Nutr201129661962822283036

- MartikainenPBartleyMLahelmaEPsychosocial determinants of health in social epidemiologyInt J Epidemiol20023161091109312540696

- HolmesWCBilkerWBWangHChapmanJGrossRHIV/AIDS-specific quality of life and adherence to antiretroviral therapy over timeJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200746332332717846560

- KuoYFRajiMAMarkidesKSRayLAEspinoDVGoodwinJSInconsistent use of diabetes medications, diabetes complications, and mortality in older mexican americans over a 7-year period: data from the Hispanic established population for the epidemiologic study of the elderlyDiabetes Care200326113054306014578239

- MizunoRFujimotoSUesugiAInfluence of living style and situation on the compliance of taking antihypertensive agents in patients with essential hypertensionIntern Med200847191655166118827412

- MurriRAmmassariADe LucaASelf-reported nonadherence with antiretroviral drugs predicts persistent conditionHIV Clin Trials20012432332911590535

- ElaminMBFlynnDNBasslerDChoice of data extraction tools for systematic reviews depends on resources and review complexityJ Clin Epidemiol200962550651019348977

- ZazaSWright-De AgüeroLKBrissPAData collection instrument and procedure for systematic reviews in the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Task Force on Community Preventive ServicesAm J Prev Med200018Suppl 1447410806979

- DeschampsAEGraeveVDvan WijngaerdenEPrevalence and correlates of nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy in a population of HIV patients using Medication Event Monitoring SystemAIDS Patient Care STDS2004181164465715633262

- NabiHVahteraJSingh-ManouxADo psychological attributes matter for adherence to antihypertensive medication? The Finnish Public Sector Cohort StudyJ Hypertens200826112236224318854766

- HaydenJACôtéPBombardierCEvaluation of the quality of prognosis studies in systematic reviewsAnn Intern Med2006144642743716549855

- de VetHCMokkinkLBTerweeCBHoekstraOSKnolDLClinicians are right not to like Cohen’s κBMJ2013346f212523585065

- StreinerDLNormanGRHealth Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use4th edNew YorkOxford University Press2008

- VerbeekJRuotsalainenJHovingJLSynthesizing study results in a systematic reviewScand J Work Environ Health201238328229022015561

- NewmanSMulliganKThe psychology of rheumatic diseasesBaillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol200014477378611092801

- OgdenJHealth Psychology: A Textbook3rd edEnglandOpen University Press2004

- PoniemanDWisniveskyJPLeventhalHMusumeci-SzabóTJHalmEAImpact of positive and negative beliefs about inhaled corticosteroids on adherence in inner-city asthmatic patientsAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol20091031384219663125

- VenturiniFNicholMBSungJCBaileyKLCodyMMcCombsJSCompliance with sulfonylureas in a health maintenance organization: a pharmacy record-based studyAnn Pharmacother199933328128810200850

- GazmararianJAKripalaniSMillerMJEchtKVRenJRaskKFactors associated with medication refill adherence in cardiovascular-related diseases: a focus on health literacyJ Gen Intern Med200621121215122117105519

- GrégoireJMoisanJGuibertRCiampiAMilotAPredictors of self-reported noncompliance with antihypertensive drug treatment: a prospective cohort studyCan J Cardiol200622432332916568157

- MillerPWikoffRLMcMahonMGarrettMJRingelKIndicators of medical regimen adherence for myocardial infarction patientsNurs Res19853452682723850486

- MolloyGJPerkins-PorrasLBhattacharyyaMRStrikePCSteptoeAPractical support predicts medication adherence and attendance at cardiac rehabilitation following acute coronary syndromeJ Psychosom Res200865658158619027448

- DelgadoJHeathKVYipBHighly active antiretroviral therapy: physician experience and enhanced adherence to prescription refillAntivir Ther20038547147814640395

- SinghNSquierCSivekCWagenerMNguyenMHYuVLDeterminants of compliance with antiretroviral therapy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus: prospective assessment with implications for enhancing complianceAIDS Care1996832612698827119

- SinghNBermanSMSwindellsSAdherence of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients to antiretroviral therapyClin Infect Dis199929482483010589897

- BottonariKARobertsJECieslaJAHewittRGLife stress and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive individuals: a preliminary investigationAIDS Patient Care STDS2005191171972716283832

- GodinGCôtéJNaccacheHLambertLDTrottierSPrediction of adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a one-year longitudinal studyAIDS Care200517449350416036235

- KacanekDJacobsonDLSpiegelmanDWankeCIsaacRWilsonIBIncident depression symptoms are associated with poorer HAART adherence: a longitudinal analysis from the Nutrition for Healthy Living studyJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr201053226627220104122

- MartiniMD’EliaSPaolettiFAdherence to HIV treatment: results from a 1-year follow-up studyHIV Med200231626412059953

- MellinsCAKangELeuCSHavensJFChesneyMALongitudinal study of mental health and psychosocial predictors of medical treatment adherence in mothers living with HIV diseaseAIDS Patient Care STDS200317840741613678542

- Nilsson SchönnessonLDiamondPMRossMWWilliamsMBrattGBaseline predictors of three types of antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence: A 2-year follow-upAIDS Care200618440741416809121

- ThrasherADEarpJAGolinCEZimmerCRDiscrimination, distrust, and racial/ethnic disparities in antiretroviral therapy adherence among a national sample of HIV-infected patientsJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr2008491849318667919

- HorneRCooperVGellaitryGDateHLFisherMPatients’ perceptions of highly active antiretroviral therapy in relation to treatment uptake and adherence: the utility of the necessity-concerns frameworkJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200745333434117514019

- MugaveroMJRaperJLReifSOverload: impact of incident stressful events on antiretroviral medication adherence and virologic failure in a longitudinal, multisite human immunodeficiency virus cohort studyPsychosom Med200971992092619875634

- CarrieriMPLeportCProtopopescuCFactors associated with nonadherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: a 5-year follow-up analysis with correction for the bias induced by missing data in the treatment maintenance phaseJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200641447748516652057

- StilleyCSDiMartiniAFde VeraMEIndividual and environmental correlates and predictors of early adherence and outcomes after liver transplantationProg Transplant20102015866 quiz 6720397348

- De GeestSAbrahamIMoonsPLate acute rejection and subclinical noncompliance with cyclosporine therapy in heart transplant recipientsJ Heart Lung Transplant19981798548639773856

- RussellCLCetingokMHamburgerKQMedication adherence in older renal transplant recipientsClin Nurs Res20101929511220185804

- WengFLIsraniAKJoffeMMRace and electronically measured adherence to immunosuppressive medications after deceased donor renal transplantationJ Am Soc Nephrol20051661839184815800121

- DewMARothLHThompsonMEKormosRLGriffithBPMedical compliance and its predictors in the first year after heart transplantationJ Heart Lung Transplant19961566316458794030

- DewMADimartiniAFDe Vito DabbsAAdherence to the medical regimen during the first two years after lung transplantationTransplantation200885219320218212623

- DobbelsFVanhaeckeJDupontLPretransplant predictors of posttransplant adherence and clinical outcome: an evidence base for pretransplant psychosocial screeningTransplantation200987101497150419461486

- DiMatteoMRSherbourneCDHaysRDPhysicians’ characteristics influence patients’ adherence to medical treatment: results from the Medical Outcomes StudyHealth Psychol1993122931028500445

- HoogendoornWEvan PoppelMNBongersPMKoesBWBouterLMSystematic review of psychosocial factors at work and private life as risk factors for back painSpine (Phila Pa 1976)200025162114212510954644

- ProperKISinghASvan MechelenWChinapawMJSedentary behaviors and health outcomes among adults: a systematic review of prospective studiesAm J Prev Med201140217418221238866

- VriezekolkJEvan LankveldWGGeenenRvan den EndeCHLongitudinal association between coping and psychological distress in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic reviewAnn Rheum Dis20117071243125021474486

- WrześniewskiKWłodarczykDSense of coherence as a personality predictor of the quality of life in men and women after myocardial infarctionKardiol Pol201270215716322427082

- CholowskiKCantwellRPredictors of medication compliance among older heart failure patientsInt J Older People Nurs20072425026220925839

- EdigerJPWalkerJRGraffLPredictors of medication adherence in inflammatory bowel diseaseAm J Gastroenterol200710271417142617437505

- FrazierPADavis-AliSHDahlKECorrelates of noncompliance among renal transplant recipientsClin Transplant1994865505577865918

- HoltEWMuntnerPJoyceCMoriskyDEWebberLSKrousel- WoodMLife events, coping, and antihypertensive medication adherence among older adults: the cohort study of medication adherence among older adultsAm J Epidemiol2012176Suppl 7S64S7123035146

- SmallsBLWalkerRJHernandez-TejadaMACampbellJADavisKSEgedeLEAssociations between coping, diabetes knowledge, medication adherence and self-care behaviors in adults with type 2 diabetesGen Hosp Psychiatry201234438538922554428

- BaileyCJKodackMPatient adherence to medication requirements for therapy of type 2 diabetesInt J Clin Pract201165331432221314869

- HawthorneABRubinGGhoshSReview article: medication non-adherence in ulcerative colitis – strategies to improve adherence with mesalazine and other maintenance therapiesAliment Pharmacol Ther200827121157116618384664

- JacksonCAClatworthyJRobinsonAHorneRFactors associated with non-adherence to oral medication for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic reviewAm J Gastroenterol2010105352553919997092

- OdegardPSCapocciaKMedication taking and diabetes: a systematic review of the literatureDiabetes Educ200733610141029 discussion 1030–103118057270

- van den BemtBJZwikkerHEvan den EndeCHMedication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a critical appraisal of the existing literatureExpert Rev Clin Immunol20128433735122607180

- WuJRMoserDKLennieTABurkhartPVMedication adherence in patients who have heart failure: a review of the literatureNurs Clin North Am2008431133153vii18249229

- AmmassariATrottaMPMurriRAdICoNA Study GroupCorrelates and predictors of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: overview of published literatureJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200231Suppl 3S123S12712562034

- RestrepoRDAlvarezMTWittnebelLDMedication adherence issues in patients treated for COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20083337138418990964

- SlavinREBest evidence synthesis: an intelligent alternative to meta-analysisJ Clin Epidemiol19954819187853053

- OvermanCLBossemaERvan MiddendorpHThe prospective association between psychological distress and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: a multilevel regression analysisAnn Rheum Dis201271219219721917827