Abstract

Background

There is evidence that both personality traits and personal beliefs about medications affect adherence behavior. However, limited research exists on how personality and beliefs about asthma medication interact in influencing adherence behavior in people with asthma. To extend our knowledge in this area of adherence research, we aimed to determine the mediating effects of beliefs about asthma medication between personality traits and adherence behavior.

Methods

Asthmatics (n=516) selected from a population-based study called West Sweden Asthma Study completed the Neuroticism, Extraversion and Openness to Experience Five-Factor Inventory, the Medication Adherence Report Scale, and the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire. Data were analyzed using confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling.

Results

Three of the five investigated personality traits – agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism – were associated with both concerns about asthma medication and adherence behavior. Concerns functioned as a partial mediator for the influencing effects of agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism on adherence behavior.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that personality traits could be used to identify individuals with asthma who need support with their adherence behavior. Additionally, targeting concerns about asthma medication in asthmatics with low levels of agreeableness or conscientiousness or high levels of neuroticism could have a favorable effect on their adherence behavior.

Introduction

Individuals’ perceptions about medication most likely have an impact on adherence behavior.Citation1–Citation3 For instance, people who express beliefs that the prescribed medication is necessary for their health are more inclined to adhere to the prescription. In contrast, those who are concerned about side effects or becoming addicted are more likely to deviate from their prescriptions.Citation1–Citation3 It has previously been reported that people with asthma expressed more concerns about their medication than did people who had been prescribed medications for renal, cardiac, or cancer conditions.Citation1 With regard to asthma medication treatment, Menckeberg et alCitation4 stated that the lowest adherence scores were found among asthmatics who had been classified as being skeptical or indifferent toward the prescribed medication. The highest adherence scores were found among asthmatics who had been classified as having an accepting attitude toward the medication. Ponieman et alCitation5 reported that having concerns about side effects or finding it difficult to follow the treatment regimen constituted risks for poor adherence. In contrast, being confident in one’s ability to use the medication, and believing that it was important to use the medication during asymptomatic periods, reduced the risk of poor adherence.

Personality contributes to people’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior.Citation6 Consequently, personality also influences an individual’s perceptions of healthCitation7 and health outcomesCitation8–Citation10 as well as their health-related behaviors, for example, adherence behavior.Citation10–Citation16 According to the Five-Factor Model (FFM),Citation17 personality can be described using five broad and bipolar personality traits: agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, and openness to experience. The personality traits are rather stable in adulthood, they have been identified in various cultures, and are evident in both women and men.Citation17 With regard to adherence behavior, people with lower levels of agreeablenessCitation16 or conscientiousnessCitation11–Citation13,Citation16 or higher levels of neuroticismCitation15,Citation16 seem more inclined to display nonadherent behavior. People with lower levels of agreeableness are more predisposed to being skeptical, reluctant, and less cooperative. People with lower levels of conscientiousness are more disorganized and non-goal oriented in disposition. People with higher levels of neuroticism could be described as anxious, moody, and less stress tolerant.Citation18

Approximately 300 million people throughout the world have asthma; despite the variation in prevalence across countries (1%–18%), asthma is regarded as a global burden.Citation19 Asthma causes substantial consequences for both society and the individual, for instance, in terms of costs for health care, medication, work absenteeism, and reduced health-related quality of life.Citation19 Through better disease control and reduction in exacerbations, the consequences of asthma could be reduced. Inadequate adherence to a treatment regimen is regarded as one of the most common causes of poor disease control in people with asthma.Citation19 Research on adherence to asthma medication treatment has shown that approximately 50% of those who had been prescribed long-term treatment displayed nonadherence, at least part of the time.Citation20,Citation21 Such lapse in managing asthma could constitute an increased risk for unsatisfactory disease control,Citation20,Citation22 leading to individual consequences such as limitations in daily life, nighttime awakenings, exacerbations, impaired lung function,Citation19 and poor health-related quality of life.Citation23 Therefore, promotion of adherence could be regarded as a cost-cutting measure.Citation24

Both personality and beliefs about medication are factors known to influence adherence, but little is known about their interaction in relation to adherence behavior. Because personality contributes to people’s thinking, feeling, and behaving,Citation6 and because personality traits are rather stable constructs,Citation17 we hypothesized that personality would be shown to affect people’s perceptions about their medication, which in turn would have an impact on their adherence behavior. In order to extend our knowledge in this specific area of adherence research, our aim was to determine the mediating effects of beliefs about asthma medication between personality traits and adherence behavior.

Material and methods

Participants

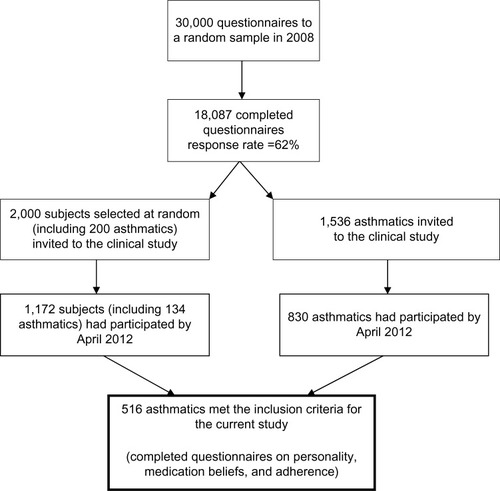

The sample was selected from a population-based study conducted in western Sweden, the West Sweden Asthma Study.Citation25 The sampling procedure is illustrated in . The participants (n=516) consisted of adults with asthma (60% women), who were born between 1933 and 1991 (mean age 47.36 years, standard deviation 15.6 years). The participants were invited to take part in the current study when they visited the research center to participate in the clinical part of the West Sweden Asthma Study between 2009 and 2012. The participants received written information combined with verbal information about the current study as well as questionnaires. Most participants completed the questionnaires at the research center, and participants who chose to bring the questionnaires home for completion received a prepaid reply envelope. Two reminders were sent to nonresponders. A completed and returned questionnaire was regarded as consent to participate. The study was approved by the regional research ethics board at the University of Gothenburg (593-08, December 18, 2008).

Measures

The data were collected using questionnaires on personality traits, beliefs about asthma medication, adherence behavior, and prescribed asthma medication treatment. Sociodemographic data were collected through structured interviews. The Neuroticism, Extraversion and Openness to Experience Five-Factor Inventory was used to assess the FFM personality traits. The inventory consists of 60 items, 12 for each personality trait, scaled 1–5.Citation18 The Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire was used to assess beliefs about prescribed asthma medications. The questionnaire consists of ten items, scaled 1–5. Five items measure concerns about the asthma medication, ie, worries about side effects, long-term effects, and becoming addicted. The remaining five items measure beliefs about the necessity of the asthma medication, ie, that both present and future health depends on the asthma medication and that medication prevents a worsening of the disease.Citation26 The Medication Adherence Report Scale consists of five items that measure adherence behavior with regard to the extent to which a person forgets to take, alters the dosage of and stops taking the asthma medication, misses out doses and takes less than instructed. The five items are scaled 1–5.Citation27 The Cronbach’s alpha scores for all scales are presented in .

Table 1 Number of items, reliability for the scales, and mean values and standard deviations (SD)

Model testing

In a mediator model, a variable functions as a mediator when it explains the association between the independent variable and the dependent variable. To qualify as a mediator in the current study, the following criteria had to be met:Citation28

The independent variable accounted for the variation in the mediator.

The mediator accounted for the variation in the dependent variable.

If the association between step 1 and step 2 were controlled for, the former significant correlation between the independent and dependent variable went to zero or decreased.

A zero is the strongest demonstration of a mediating effect. A decrease in the previous association was regarded as a partial mediating effect, which indicated that, like other phenomena, there are several factors underlying adherence, not only personality and medication beliefs. Therefore a decrease rather than a zero may be more realistic.Citation28

One path model for each personality trait was constructed. The personality traits were treated as independent variables, adherence as a dependent variable, and medication belief as a mediator. In the path model, it was first determined whether the independent variable, ie, the personality trait, had a direct effect on the dependent variable, ie, adherence. Second, whether or not the independent variable accounted for the variation in the mediator was checked. If so, the first criterion was met. Thereafter, it was determined whether the mediator accounted for the variation in the dependent variable. If so, the second criterion was met. In the next step, it was checked whether the previous significant association between the independent and the dependent variable decreased or went to zero in the path model when paths to and from the mediator were introduced. If so, the third and final criterion was met.Citation28 Finally, in order to determine the total effect on the independent variable, the effects from the different paths were summed.

Analysis

In order to investigate the mediating effects of beliefs about asthma medication between personality traits and adherence behavior, confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling technique with latent variables were used.

Latent variables reflect hypothetical constructs and are estimated based on the relations among two or more observed variables (indicators). In areas such as the assessment of traits, it is implausible to assume that the conceptual variables can be measured without appreciable error.Citation29 Measurement of traits always includes error components. The use of latent variables permits the estimation of relationships among observed variables and theoretically interesting constructs that are free from the effects of such measurement unreliability. Factor analysis divides the variance in the observed variables into three variance components: first, true score common variance related to the construct or constructs of interest; second, a component that is reliable and specific to the variable; and third, a variance component that represents measurement error. That is to say, one way to solve the problem of measurement error is to use a latent variable approach.Citation30

Goodness of fit

The analyses were carried out using the statistical modeling program Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA), version 5Citation31 under the STREAMSCitation32 environment. As measures of model fit, the χ2 goodness-of-fit test, the root mean square error of approximation, and the standardized root mean square residual assessment were used. The root mean square error of approximation is strongly recommended as a tool when evaluating model fit, as it takes into account both the number of observations and the number of free parameters. An acceptable model fit is indicated by values of less than 0.08, while values of less than 0.05 imply a good model fit. Standardized root mean square residual can range from 0–1, where 0 is indicative of a perfect model fit, and values of 0.08 or smaller indicate an acceptable model fit.Citation33 When evaluating model fit, the reasonableness of parameter estimates was also considered.

Missing data

The total amount of internal missing data for the seven scales was 1,127 (6.7%) scores distributed across the 75 items. To include all of the collected information, the missing data modeling procedure implemented in the Mplus program was used.Citation34 This modeling procedure is based on the assumption that the data is “missing at random”, which is a much less restrictive assumption than the assumption that the data is “missing completely at random.” The basic principle is that subsets of cases with a particular pattern of missing observations each have a separate covariance matrix, where the matrices are combined into one total matrix.Citation32,Citation34 That implies that the procedure yields unbiased estimates when the missing value is random, given the information in the data. The fact that there are relatively high interrelations among the observed variables provides good possibilities to satisfy the missing at random assumption.Citation35,Citation36

Results

Medication beliefs as mediators

Three of the five investigated personality traits – agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism – were associated with both adherence behavior and concerns about the asthma medication. Openness to experience was associated with concerns, but no associations were identified between this personality trait and adherence. No associations were found between extraversion and adherence and medication beliefs. The belief that the asthma medication was a necessity for present and future health was associated with adherence behavior, but not with any of the personality traits (). Consequently, the variables extraversion, openness to experience, and beliefs that the asthma medication was a necessity were excluded from further analysis. Reports on prescribed asthma medication treatment are presented in . The amount of internal missing data across the five remaining scales (agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, concerns, and adherence) and 46 items was 783 scores or 5.9%. Three path models with the personality traits as independent variables, adherence as a dependent variable, and medication concerns as a mediator were constructed. The goodness of fit was acceptable in all three models ().

Table 2 Standardized factor loadings between latent variables for personality traits, medication beliefs, and adherence

Table 3 Prescribed asthma medications

Table 4 Goodness of fit indexes for models A, B, and C

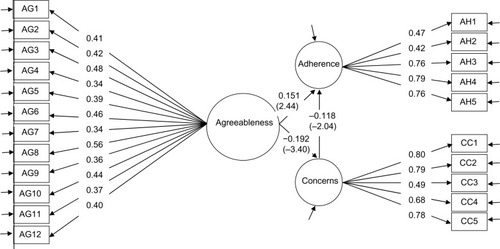

Agreeableness

The path model including agreeableness, concern, and adherence showed a significant path between agreeableness and adherence (0.151), meaning that agreeableness had a direct effect on adherence. Furthermore, the paths between agreeableness and concern (−0.192) and concern and adherence (−0.118) were also significant, which means that concern functioned as a partial mediator for the influencing effect of agreeableness on adherence (). The total effect on adherence was the direct and mediating effect together (−0.192) × (−0.118) + 0.151 = 0.174, which corresponded with the standardized correlation coefficient between agreeableness and adherence (). Therefore, concern qualified as a mediator for the influencing effect of agreeableness on adherence.

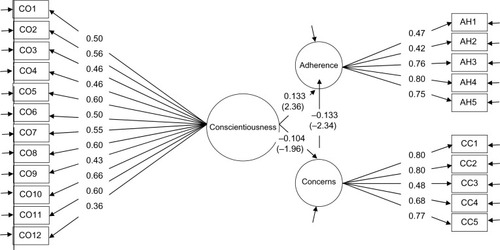

Conscientiousness

The path model with conscientiousness as the independent variable showed a significant path between conscientiousness and adherence (0.133), meaning that conscientiousness had a direct effect on adherence (). The paths between conscientiousness and concern (−0.104) and concern and adherence (−0.133) were significant as well, which means that concern partially mediated the effect of conscientiousness on adherence. The total effect on adherence consisted of the direct and mediated effect together (−0.104) × (−0.133) + 0.133 = 0.147, which corresponded with the standardized correlation coefficient between conscientiousness and adherence (). Therefore, concern qualified as a mediator for the influencing effect of conscientiousness on adherence.

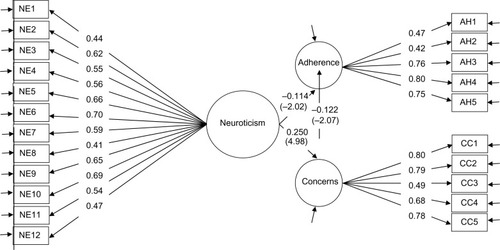

Neuroticism

The path model with neuroticism as the independent variable showed that this personality trait had a direct effect on adherence (), as there was a significant path between these two variables (−0.114). The paths between neuroticism and concern (0.250) and adherence (−0.122) were significant too, which means that concern functioned as a partial mediator for the influencing effect of neuroticism on adherence. The total influencing effect of neuroticism on adherence was the direct and mediating effect together 0.250 × (−0.122) + (−0.114) = −0.145, which corresponded with the standardized correlation coefficient between neuroticism and adherence (). Therefore, concern qualified as a mediator for the influencing effect of neuroticism on adherence.

Discussion

The current findings reinforce the significance of both personality and medication beliefs in relation to adherence behavior. However, the study is unique in that it explores the joint effect of personality and medication beliefs on adherence to asthma medication. Three of the five investigated personality traits were associated with both perceived concerns about the asthma medication and adherence behavior: agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism. Thus, medication beliefs functioned as a mediator for the influencing effects of three of the five FFM personality traits on adherence behavior.

The main focus of the present study was on evaluating the function of medication beliefs as a mediator between personality and adherence behavior. Based on the findings, it would seem reasonable to argue that personality can be used to identify individuals with asthma who are at risk for poor adherence to asthma medication therapy. In the path models, we were able to show the direct effects of three personality traits on adherence, revealing that asthmatics with low levels of agreeableness or conscientiousness or high levels of neuroticism tend to be more inclined to display poor adherence behavior. At the same time, they expressed more concerns about the medication. Therefore, the findings suggest that addressing medication concerns in people with these personality characteristics, with a view to reducing their concerns, could have a favorable effect on their adherence behavior. Previous interventions addressing beliefs about asthma medication have proved useful in increasing adherence in people with asthma.Citation37,Citation38 With the addition of personality in similar interventions, people at risk for displaying poor adherence could be identified, and assistance could be provided to those most in need. Furthermore, an awareness of the importance of patients’ individual differences could guide and inspire health care personnel in their encounters with patients with different personality characteristics when providing adherence support.

The present study confirmed previous findings in this specific area of adherence research. First, by showing that previously reported associations between the FFM personality traits and adherenceCitation11–Citation13,Citation15,Citation16 are also valid for adherence behavior in people with asthma. Second, the current study identified associations between medication beliefs and adherence to asthma medication similar to associations reported previously.Citation4,Citation5 Additionally, the study discerned associations between personality traits and beliefs about asthma medication. Participants with low levels of agreeableness or conscientiousness or high levels of neuroticism had more concerns about their prescribed asthma medication. These findings both confirm and contradict our previous studyCitation39 in which we showed that neuroticism was positively associated with medication concerns, which is in line with the current study. However, our previous studyCitation39 also identified associations between extraversion and concerns and between conscientiousness and necessity, which we did not find in the current study. These dissimilarities may be due to sample size and/or sampling procedure. The current study has its origin in a population-based study, meaning that the present sample has better representativeness than our previous study.Citation39 However, further investigation may be needed before any conclusions can be drawn.

People with low levels of agreeableness are by nature more predisposed to being skeptical and distrustingCitation18 – personality characteristics that could influence their thinking about asthma medication. Low levels of conscientiousness are associated with a low degree of motivation in goal-directed behavior, andCitation18 less conscientious persons also seem to be generally prone to living a less healthy lifestyle.Citation40 These tendencies could possibly explain these individuals’ negative attitude toward asthma medication in the current study. Moreover, participants with high levels of neuroticism were more prone to having concerns about their asthma medication. High scores on this personality trait are associated with behavioral tendencies, like being worried,Citation18 which could explain their proneness to experiencing medication-related concerns.

It is to be noted that the strongest correlation between adherence and the other investigated variables was found between necessity and adherence. This finding is in line with previous research,Citation1,Citation4 which emphasized that beliefs that the asthma medication is a necessity for the present and future health, for instance, also constitute a significant target in efforts to improve adherence. However, based on the current findings, we also need to take patients’ different personality characteristics and concerns with their asthma medication into consideration.

Methodological considerations

One strength of the current study is that the sample was selected from a population-based study, which increases the possibility of applying the present findings to individuals with asthma in general. Nevertheless, an additional strength was the use of structural equation modeling to test the theoretical relationships between personality traits, medication beliefs, and adherence behavior. Path models provide an estimation of the effects between the variables in the theoretical model.Citation41 Use of this statistical analysis enables the identification of mediators that predict the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable prior to an intervention. If a hypothesized model turns out to be correct, it can be assumed that intervening to change the mediator would in turn affect the outcome.Citation42 For that reason, it is important that the hypothesized models be designed only after careful theoretical consideration.Citation41 We used personality traits as independent variables, meaning that the other variables did not influence the traits. This assumption was made based on the theoretical consideration that, according to the FFM, personality traits have a strong biological base, leading to a high degree of stability in personality during adulthood.Citation17 Another reason for treating the personality traits as independent variables was that personality influences our thoughts, feelings, and behavior.Citation6 Treating medication beliefs as mediators was based on previous research describing beliefs about asthma medication as predictors of adherence.Citation5 As regards reliability, the Cronbach’s alpha scores for the scales were acceptable, although in two cases they were either exactly at or only slightly above the normal cut-off point (0.70) for reliability. However, because latent variables are free from sources of influence irrelevant to the hypothetical construct intended to be captured, the problem associated with a somewhat mediocre alpha estimate does not arise, provided that the model fit is acceptable. Indeed, the model fit for the three investigated hypothetic models was acceptable.Citation33 One weakness in the study was the sparse data on the socioeconomic characteristics of the participants, but all available data such as age, sex, and prescribed asthma medication were shown. Another possible limitation of the study was that adherence was measured using self-reports, which could result in overestimation of adherence. However, considering the study design, self-report was the most suitable method of assessing adherence behavior.

Conclusion

Both personality and beliefs about asthma medication play a role in adherence behavior in people with asthma. Addressing concerns about asthma medication and trying to reduce such concerns, primarily in asthmatics with low levels of agreeableness or conscientiousness or high levels of neuroticism, would most likely lead to positive effects on adherence.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by unrestricted grants from the VBG GROUP Centre for Asthma and Allergy Research, Herman Krefting Foundation against Asthma and Allergy and GlaxoSmithKline.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HorneRWeinmanJPatients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illnessJ Psychosom Res199947655556710661603

- CliffordSBarberNHorneRUnderstanding different beliefs held by adherers, unintentional nonadherers, and intentional nonadherers: application of the Necessity-Concerns FrameworkJ Psychosom Res2008641414618157998

- PhatakHMThomasJRelationships between beliefs about medications and nonadherence to prescribed chronic medicationsAnn Pharmacother200640101737174216985088

- MenckebergTTBouvyMLBrackeMBeliefs about medicines predict refill adherence to inhaled corticosteroidsJ Psychosom Res2008641475418157999

- PoniemanDWisniveskyJPLeventhalHMusumeci-SzabóTJHalmEAImpact of positive and negative beliefs about inhaled corticosteroids on adherence in inner-city asthmatic patientsAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol20091031384219663125

- PervinLACervoneDPersonality: Theory and Research10th edHoboken, NJWiley2008

- GoodwinREngstromGPersonality and the perception of health in the general populationPsychol Med200232232533211866326

- ChapmanBDubersteinPLynessJMPersonality traits, education, and health-related quality of life among older adult primary care patientsJ Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci2007626P343P35218079419

- DubayovaTNagyovaIHavlikovaENeuroticism and extra-version in association with quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s diseaseQual Life Res2009181334218989757

- AxelssonMEmilssonMBrinkELundgrenJTorénKLötvallJPersonality, adherence, asthma control and health-related quality of life in young adult asthmaticsRespir Med200910371033104019217764

- ChristensenAJSmithTWPersonality and patient adherence: correlates of the five-factor model in renal dialysisJ Behav Med19951833053137674294

- StilleyCSSereikaSMuldoonMFRyanCMDunbar-JacobJPsychological and cognitive function: predictors of adherence with cholesterol lowering treatmentAnn Behav Med200427211712415026295

- O’CleirighCIronsonGWeissACostaPTJrConscientiousness predicts disease progression (CD4 number and viral load) in people living with HIVHealth Psychol200726447348017605567

- EdigerJPWalkerJRGraffLPredictors of medication adherence in inflammatory bowel diseaseAm J Gastroenterol200710271417142617437505

- BruceJMHancockLMArnettPLynchSTreatment adherence in multiple sclerosis: association with emotional status, personality, and cognitionJ Behav Med201033321922720127401

- AxelssonMBrinkELundgrenJLötvallJThe influence of personality traits on reported adherence to medication in individuals with chronic disease: an epidemiological study in West SwedenPLoS One201163e1824121464898

- McCraeRRCostaPTJrPersonality in Adulthood: A Five-Factor Theory Perspective2nd edNew York, NYGuilford Press2003

- CostaPTJrMcCraeRRRevised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional ManualOdessa, FLPsychological Assessment Resources1992

- Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention [webpage on the Internet]Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA)2011 Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org/Accessed November 29, 2012

- ClatworthyJPriceDRyanDHaughneyJHorneRThe value of self-report assessment of adherence, rhinitis and smoking in relation to asthma controlPrim Care Respir J200918430030519562233

- LatryPPinetMLabatAAdherence to anti-inflammatory treatment for asthma in clinical practice in FranceClin Ther200830Spec No1058106818640480

- KrishnanJARiekertKAMcCoyJVCorticosteroid use after hospital discharge among high-risk adults with asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2004170121281128515374842

- LisspersKStällbergBHasselgrenMJohanssonGSvärdsuddKQuality of life and measures of asthma control in primary health careJ Asthma200744974775117994405

- BenderBGRandCMedication non-adherence and asthma treatment costCurr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol20044319119515126940

- LötvallJEkerljungLRönmarkEPWest Sweden Asthma Study: prevalence trends over the last 18 years argues no recent increase in asthmaRespir Res2009109419821983

- HorneRWeinmanJHankinsMThe beliefs about medicines questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medicationPsychol Health1999141124

- HorneRWeinmanJSelf-regulation and self-management in asthma: exploring the role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs in explaining non-adherence to preventer medicationPsychol Health20021711732

- BaronRMKennyDAThe moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerationsJ Pers Soc Psychol1986516117311823806354

- MaruyamaGMBasics of Structural Equation ModellingThousand Oaks, CASage Publications1998

- GustafssonJEStahlPASTREAMS 1.7 User’s GuideMölndal, SwedenMultivariate Ware1997

- MuthénLKMuthénBOMplus User’s GuideFifth EditionLos Angeles, CAMuthén and Muthén1998–2007

- GustafssonJEStahlPASTREAMS 3.0 User’s GuideMölndal, SwedenMultivariate Ware2005

- BrownTAConfirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied ResearchNew York, NYGuilford Press2006

- MuthénBKaplanDHollisMOn structural equation modeling with data that are not missing completely at randomPsychometrika1987523431462

- AllisonPDMissing data techniques for structural equation modelingJ Abnorm Psychol2003112454555714674868

- SchaferJLGrahamJWMissing data: our view of the state of the artPsychol Methods20027214717712090408

- ParkJJacksonJSkinnerERanghellKSaiersJCherneyBImpact of an adherence intervention program on medication adherence barriers, asthma control, and productivity/daily activities in patients with asthmaJ Asthma201047101072107721039215

- BenderBGApterABogenDKTest of an interactive voice response intervention to improve adherence to controller medications in adults with asthmaJ Am Board Fam Med201023215916520207925

- EmilssonMBerndtssonILötvallJThe influence of personality traits and beliefs about medicines on adherence to asthma treatmentPrim Care Respir J201120214114721311839

- BoggTRobertsBWConscientiousness and health-related behaviors: a meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortalityPsychol Bull2004130688791915535742

- SchumackerRELomaxRGA Beginner′s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling2nd edMahwah, NJLawrence Erlbaum Associates2004

- MackinnonDPFarichildAJFritzMSMediation analysisAnnu Rev Psychol20075859361416968208