Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of nonadherence in a cohort of renal transplant recipients (RTRs) and to evaluate prospectively whether more intense clinical surveillance and reduced pill number enhanced adherence.

Patients and methods

The study was carried out in 310 stable RTRs in whom adherence, life satisfaction, and transplant care were evaluated by specific questionnaires (time 0). The patients under tacrolimus (TAC; bis in die [BID]) were then shifted to once-daily TAC (D-TAC) to reduce their pill burden (Shift group) and were followed up for 6 months to reevaluate the same parameters. Patients on cyclosporin or still on BID-TAC constituted a time-control group.

Results

The prevalence of nonadherence was 23.5% and was associated with previous rejection episodes (P<0.002), and was inversely related to Life Satisfaction Index, anxiety, and low glomerular filtration rate (minimum P<0.03). Nonadherent patients were significantly less satisfied with their medical care and their relationships with the medical staff. A shift from BID-TAC to D-TAC was performed in 121 patients, and the questionnaires were repeated after 3 and 6 months. In the Shift group, a reduction in pill number was observed (P<0.01), associated with improved adherence after 3 and 6 months (+36%, P<0.05 versus basal), with no change in controls. Decreased TAC trough levels after 3 and 6 months (−9%), despite a slight increase in drug dosage (+6.5%), were observed in the Shift group, with no clinical side effects.

Conclusion

The reduced pill burden improves patients’ compliance to calcineurin-inhibitors, but major efforts in preventing nonadherence are needed.

Introduction

Ten years ago, the World Health Organization declared nonadherence to treatment as a major public health problemCitation1 that may result in disease progression, increased health care costs, and even premature death in patients with chronic diseases,Citation2 including renal transplant recipients (RTRs), especially prone to nonadherence because of the complexity and lifelong character of their immunosuppressive therapeutic regimen.Citation3

In clinical controlled trials, nonadherence to treatment ranges between 43% and 78%,Citation2 and similar results are described with immunosuppressive agents (ISAs) in RTRs (18%–68%), with such wide ranges reflecting the difficulty of correctly defining and quantifying the phenomenon.Citation4–Citation7

A recent consensus conference concluded that nonadherence to ISAs “is more prevalent than previously assumed, is difficult to measure accurately, confers worse outcomes, occurs for a variety of reasons, and is hard to change from a behavioral perspective.”Citation8 Therefore, it is not surprising that nonadherence represents the third-leading cause of graft loss after rejections and infections,Citation9 is associated with reduced 5-year graft survival,Citation10 has sevenfold-higher odds of graft loss,Citation11 and accounts for about half of the graft failures due to rejection.Citation12

Nonadherence is a complex and challenging problem, and a better knowledge of its basis and of its appropriate remedies could dramatically improve transplant outcomes, since understanding patient behaviors and their daily problems with grafts could clarify the mechanisms leading to it.

It is well documented that patients’ lack of education regarding ISAs and the frequency of drug doses are two important factors leading to nonadherence,Citation7,Citation13 as well as that the reduction of pill burden and patient education should be considered as priorities for action to improve therapeutic adherence, these being the easiest to modify.Citation14 The recent introduction to the market of a once-daily tacrolimus formulation (D-TAC) offered the opportunity to evaluate whether the shift from a double (bis in die [BID]-TAC) to a single daily administration of the drug may enhance adherence by reducing the number of pills.

A randomized trial by Kuypers et al recently showed that the switch to D-TAC significantly improved implementation by patients of the therapeutic regimen compared to patients continuing BID-TAC during a 6-month follow-up period.Citation15 Our first goal was to confirm these data and to offer further information about different factors potentially involved in determining nonadherence.

Therefore, the aims of the present study were 1) to evaluate the prevalence of nonadherence to calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) in a cohort of stable RTRs through specific questionnaires, and 2) to ascertain whether a reduction in CNI pill numbers and an “educational plan” (written and oral information associated with more intense clinical surveillance) may prospectively influence nonadherence. As a secondary end point, we also examined the pharmacokinetics of D-TAC to verify its efficacy compared to BID-TAC, since data reported in the current literature are not univocal.

Patients and methods

Study design

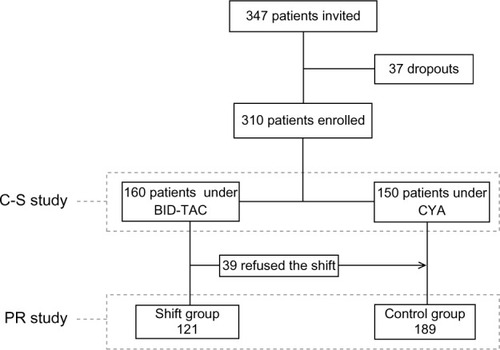

This was an observational, open-labeled, nonrandomized study. Participation in the study was proposed to 347 RTRs regularly visiting our clinic as outpatients, all first transplants from deceased donors. Inclusion criteria were: age >18 years, transplant vintage >1 year, absence of cognitive impairment, and ability to read and understand the meaning of questionnaires. Three questionnaires were proposed to all the eligible patients visited during an 8-month time frame to evaluate the prevalence of nonadherence (cross-sectional study, ). Subsequently, all the patients treated with BID-TAC were invited to take D-TAC to reduce the cumulative daily number of pills (Shift group), whereas patients on cyclosporine and those on BID-TAC refusing the shift (n=39) constituted a time-control group; follow-up of these patients lasted 6 months, in which adherence was reevaluated after 3 and 6 months (prospective study, ). Thirty-seven patients dropped out of the study: 27 patients due to the need to modify their therapies, since as a prerequisite the patients had to maintain the same daily number of pills throughout the follow-up period, and ten subjects returned to BID-TAC for clinical (gastrointestinal upset, tremors) or bureaucratic reasons; therefore, the basal data refer to 310 patients, 160 under BID-TAC and 150 under cyclosporine.

Cross-sectional study (time 0)

To analyze the prevalence of nonadherence, three short questionnaires were proposed to the patients during their medical visit (T0). The first two questionnaires were elaborated for the Transplant Learning Center Program,Citation16 aimed at improving and preserving graft function through a better knowledge of the factors affecting the life of RTRs. The sum of the single-item scores, based on a 5-point Likert scale (0–4), leads to the formulation of two indices: 1) the Life Satisfaction Index (LSI), based on eight questions (score 0–32, with higher values denoting better quality of life); and 2) the Transplant Care Index (TCI), based on six questions (score 0–24, with higher values denoting easier care). Both questionnaires were designed to serve as single composite measures to track transplant-specific quality of life and several issues related to caring for the graft (see Supplementary material).

The third questionnaire was represented by the Immunosuppressant Therapy Adherence Scale (ITAS), based on a four-item scale developed to indicate if transplant recipients were nonadherent to ISAs.Citation17 The items of ITAS are designed to explore how often in the last 3 months the patients forgot to take their ISAs, were careless about taking their ISAs, stopped taking their ISAs because they felt worse, missed taking their ISAs for any reason. For each item, the scores were: 3= perfect compliance, ie, 0% nonadherence; 2= 1%–20% nonadherence; 1= 21%–50% nonadherence; and 0= nonadherence greater than 50% of the time. Item responses are summed (range 0–12), with the highest score indicating perfect adherence to ISAs. Cukor et alCitation18 recently categorized three possibilities based on the level of patients’ compliance: perfect adherence (score 12/12), nearly perfect adherence (score 10–11/12), and less than perfect adherence (score ≤9/12); in our study, only adherence to CNIs was evaluated by ITAS, and all patients with a score ≤10 were considered nonadherent. A specific question was also made to evaluate the presence of anxiety, as previously reported.Citation19

Prospective study

For clinical and ethical reasons, the shift was proposed to all patients previously treated with BID-TAC. After basal evaluation, 121 of 160 patients accepted the conversion to D-TAC (same milligram-for-milligram total daily dose), and constituted the Shift group; patients on cyclosporine and the remaining 39 patients on BID-TAC defined the time-control group (n=189). After the basal questionnaires, the patients of both groups received a printed booklet (“Welcome in the World of Transplantation!,” written by MS, NextHealth publishers, Milan, Italy), in which the most common problems of transplant care are easily and extensively reported; the aim and the content of the booklet was explained to the patients, who were strongly encouraged to read it.

Blood samples were withdrawn 7 and 14 days after the beginning of follow-up, to ensure that similar preshift TAC trough levels were reached in the Shift group, modifying the dose of D-TAC when necessary. In control patients, blood was withdrawn to confirm the stability of CNI trough levels. No further modification in D-TAC dose was made in the following months. Three and 6 months after the basal interview (T3 and T6, respectively), the patients were administered the same questionnaires during scheduled visits.

The patients of both groups had the same number of visits and of blood withdrawals throughout the study. The study was performed in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

D-TAC pharmacokinetics

In the Shift group, the average value of the last three determinations of BID-TAC trough levels was considered as basal value of the preconversion period. After the shift to D-TAC, blood concentrations of the drug were measured after 7 and 15 days, and then after 3 and 6 months (T3 and T6, respectively).

Blood drug concentrations were measured by the Architect tacrolimus immunoassay (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA), with a lower limit of detection of 1.5 ng/mL and a standard curve range of 0–30 ng/mL.Citation20

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Continuous variables are reported as means ± standard deviation. Comparisons of continuous variables with normal distribution were performed by Student’s unpaired t-test. For variables with nonnormal distribution, we used unpaired Wilcoxon’s nonparametric test. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and were analyzed by χ2 test.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to identify baseline factors associated with a risk of non-adherence (ITAS <10) at baseline. The model was built by identifying a priori the main potential determinants of nonadherence. The model accounted for demographic (age, sex, job activity, years of school, marital status) and clinical characteristics (diabetes, body mass index, dialysis and transplantation vintage, rejection episodes, anxiety, glomerular filtration rate [GFR]) and questionnaire scores (LSI, TSI).

Doses and trough levels obtained during D-TAC treatment were compared to mean values of BID-TAC treatment by repeated-measures analysis of variance. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Cross-sectional study

reports demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients under study, and shows well-preserved renal function and satisfactory laboratory data, despite quite a long transplant vintage.

Table 1 Main data of the whole cohort of patients, and of adherent and nonadherent patients according to the ITAS score (≤10) at baseline

According to our classification, 73 patients were non-adherent (23.5%): 54 of them (71%) had an ITAS score of 10, and the remaining 19 had a score ≤9. All these patients acknowledged forgetfulness as the primary reason for their lower compliance, with some of them feeling worse after CNI administration (3.5%) or careless about taking their medications (2.9%).

LSI and TCI scores averaged 84.0% and 77.5% of their respective maximal scores, denoting a satisfactory quality of life and only minor “barriers” to adequate graft care. When the patients were divided into adherent and nonadherent groups, some differences were noted in marital status and presence of anxiety, higher in adherent patients, whereas rejection episodes were significantly higher in nonadherent patients.

Compared to compliant patients, nonadherent patients showed a reduction in both LSI (P<0.0005) and TCI (P<0.006), with interesting differences in specific items of both indices that mostly indicated difficult relationships with either their partners or the transplant team, and the presence of specific “barriers” to an adequate transplant care ().

Table 2 Main significant differences in average scores of specific items of Life Satisfaction Index and Transplant Care Index between adherent and nonadherent patients

The logistic regression analysis () showed that nonadherence to CNIs was significantly predicted by previous rejection episodes (P<0.002), whereas the presence of high LSI values and anxiety represented “protective factors”, favoring patients compliance; interestingly, GFR values below 60 mL/minute were associated with better adherence, but no relationship was observed with the cumulative number of pills, age, sex, living with a partner, or level of school education.

Table 3 Factors predictive of nonadherence at baseline in the whole cohort of patients (n=310)

Prospective study

In the prospective study, the patients were divided into two groups: the Shift group, which included patients accepting the shift to D-TAC (n=121), and the time-control group, which consisted of 150 patients on cyclosporine and 39 on BID-TAC refusing the shift (n=189) who had similar demographic characteristics. Beyond the differences in CNI use, significant differences in the controls were observed in transplant vintage, rejection episodes, and LSI score.

At T0 (), the prevalence of nonadherent patients and the cumulative daily number of pills were similar in the two groups under study. The conversion to D-TAC in the Shift group resulted in a significant and stable reduction in the daily number of pills (10.7±4.1 versus (vs) 13.3+4.7, P<0.01), which conversely did not vary throughout the study in the control group.

Table 4 Basal data (T0) of the patients of the Shift and control groups

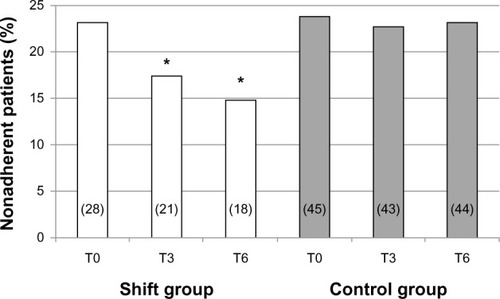

Three months after the shift (T3), adherence in the Shift group significantly improved: seven patients reached an ITAS score >10 (P<0.05 vs T0), and a further three subjects became adherent at T6 (P<0.05 vs T0); conversely, no change was observed in the time-control group ().

Figure 2 Prevalence of nonadherence in the two groups under study throughout the observation period, expressed as percentage value; the absolute number of patients is reported in columns (T0 = basal; T3 and T6 = after 3 and 6 months of follow-up, respectively).

There was a modest though significant reduction in LSI observed at T0 in the control group compared to the Shift group (), which persisted throughout the study; conversely, TCI score was similar between the two groups at baseline and did not vary thereafter.

No significant modification was observed in estimated GFR or in the main laboratory data in both groups, and no rejection episodes or infectious diseases were recorded throughout the follow-up period. Twelve patients complained of minor side effects (pruritus, tremors, gastrointestinal upset) that did not require treatment.

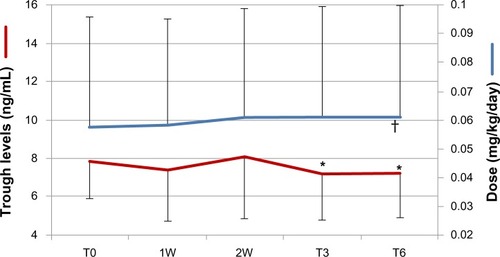

D-TAC pharmacokinetics

Data of the pharmacokinetic study are represented in . After the shift, small adjustments of D-TAC doses were necessary on days 7 and 15 (+1.7% and +6.5% vs T0, respectively; P<0.03), to bring drug concentrations back to basal values; no further change was made thereafter. After 3 and 6 months of D-TAC fixed doses, trough levels progressively declined (−8.7% and −9.2% vs T0, respectively, both P<0.03), but always remained in the recommended therapeutic range.

Figure 3 Doses (blue line) and trough levels (red line) of once-daily tacrolimus (D-TAC) throughout the observation period in patients of the Shift group. T0 represents the mean value of the last three bis in die TAC trough levels and doses before the shift; 1W and 2W represent the determinations of trough levels 1 week and 15 days after the shift and the consequent changes in D-TAC doses; T3 and T6 represent the modifications in D-TAC trough levels after 3 and 6 months of follow-up, when the doses of D-TAC were fixed.

Discussion

The results of the present study confirm the high prevalence of nonadherence to CNIs in our RTRs, and demonstrate that the pill burden represents an obstacle to patients’ compliance to CNIs. However, despite the significant improvement in patients’ adherence after the shift to D-TAC, these data prove that 64% of nonadherent patients did not change their behavior, even when the number of pills was reduced and greater clinical attention was provided.

Since nonadherence to ISAs is the leading preventable cause of graft loss, to identify noncompliant patients should represent a priority for the transplant team. There are many factors associated with nonadherence: lack of appropriate instructions from health care providers, elevated number of pills, forgetfulness, intentional failure to consume the medication, and drug adverse effects.Citation21 It seems clear that a greater effort by medical teams in offering appropriate education and the widest reduction of the “barriers” that may favor nonadherence should be combined to modify patients’ wrong habits.

A recent consensus conferenceCitation14 established three priorities of action to reduce the incidence of nonadherence to ISAs – lower pill burden, better patient education, and adequate peer support for patients – as the easiest factors to modify. This justifies our focus on these priorities, evaluated by LSI and TCI, and also psychological or practical barriers that may condition patients’ compliance.

The prevalence of nonadherence was substantially high, despite our “strict” definition of nonadherence (ITAS score ≤10); some studies, in fact, claim an adherence <80% (ITAS <10) as the minimum thresholdCitation22,Citation23; our choice takes into account that questionnaires underestimate the prevalence of nonadherence, due to the reluctance of patients to admit their mistakes or to the limits of their memory.Citation24 Nonetheless, compared to electronic devices, pharmacy records, or drug-level monitoring, questionnaires represent a reliable source in evaluating nonadherence in large cohorts of patients, despite their inherent limitations. In particular, ITAS has been validated by correlating composite item scores with refill-record adherence rates, serum ISA concentrations, and episodes of graft rejection or increased serum creatinine,Citation17 and is practical, feasible, and cost-effective.

In this study, the main predictor of nonadherence was the previous presence of rejection episodes, an obvious consequence of low compliance to immunosuppressors. Positive factors in preventing it were a better quality of life, which certainly predisposes to better care of the graft, and the presence of anxiety or lower levels of GFR, probably a consequence of the greater attention to medical prescriptions by patients who fear to lose their graft. Contrary to previous studies, no relationship was observed with sex, marital status, or level of education, which was quite low in our patients.Citation9,Citation11,Citation25

An interesting finding of the cross-sectional study was the difference in specific items of both LSI and TCI between adherent and nonadherent patients, which showed how these latter patients had difficult relationships with the transplant team, lower satisfaction with the health care they receive, or difficulties in attending the scheduled visits. These patients clearly need greater attention from medical personnel, stressing our crucial role in enhancing therapeutic compliance.

Beyond the beneficial effects of the reduced pill burden on adherence, reported in different solid-organ grafts,Citation15,Citation26,Citation27 our prospective study offers additional information about the education of patients and closer clinical surveillance.

The absolute lack of changes in patients’ adherence in our time-control group, despite considerably greater clinical attention, clearly suggests that any educational plan should start immediately after the transplant, and should be intensively maintained thereafter by dedicated personnel,Citation28 due to the refractoriness of these patients to modify consolidated habits in the long term.

Our data suggest that D-TAC may represent an option to increase patients’ compliance, despite its higher cost (+5.4%), since its pharmacokinetic profile is comparable to BID-TAC, with only minor dose adjustments and fluctuations of its plasma levels that did not expose the patients to rejection episodes or undesirable side effects. Indeed, reductions in blood TAC concentrations averaged 9.2% after 6 months of follow-up, a value quite different from the one reported in a recent retrospective study, in which the shift to D-TAC determined a 21.7% decrease in trough levels despite the concomitant rise in its doses (17.2%), during a 6-month follow-up.Citation29 Differences in patients’ demographics, in their therapeutic compliance, or in pharmacogenomics may account for this discrepancy. Our data, however, are in line with those by Guirado et al,Citation30 who found a similar decrease in TAC trough levels after the shift (–9.2%), with a small increase in dose (+1.24%).

The main limit of the study derives from its observational nature and the unavoidable selection bias of patients of the prospective study. As a consequence, differences existed at baseline between the groups in transplant time, rejection episodes, and LSI score that make any comparison difficult. It must be stressed, however, that the control group was just a time-control group, in which the pill burden did not vary, useful in understanding, although indirectly, the effects of our “educational plan”. According to this point of view, differences in transplant vintage or in rejection rate should not influence the interpretation of data, considering also that the prevalence of nonadherence was comparable between the groups at baseline.

Instead, a strength of the paper resides in the effort of maintaining the same pill burden and in providing identical clinical surveillance to all patients throughout the follow-up period. It is well known, in fact, that the frequency of visits and blood withdrawals may positively affect patients’ compliance.Citation30

In conclusion, this study confirms that therapeutic adherence is a multidimensional phenomenon determined by the interaction of different “dimensions”, of which patient-related factors represent just one variable. Our study demonstrates that pill burden helps to reduce nonadherence, but the common belief that patients are solely responsible for taking their treatment is misleading and does not consider how other factors, also related to health care providers, may affect the patients’ capability to comply with our prescriptions.

Therefore, if it is strongly advisable to consider the total number of pills when providing optimal therapy to any patient, we should not forget difficult relationships with the medical team of nonadherent patients, which represent an important factor leading to wrong behaviors.

Greater effort should be made to assure patients’ compliance to treatment, keeping in mind that adherence requires a lifelong commitment from both patients and clinicians and that we tend to overestimate patients’ understanding and consciousness. This, associated with the reduced pill burden, a careful and early “educational plan”, and an increased number of visits when nonadherence is even suspected, might lead to improved compliance and a better outcome of the graft.

Supplementary material

The transplant learning center indices

Life satisfaction index

Please rate your satisfaction with each of the following in your life within the last month:

Your overall health

Your relationship with the people who provide your medical care

The health care you have received

Your relationship with your spouse/partner

Your ability to do things for yourself

Your appearance

The amount of control you have over your life

Your life in general.

Five-item scale (0–4, very dissatisfied–very satisfied); maximum score 32, with higher scores denoting a better quality of life.

Transplant care index

Please rate the level of difficulty you have with the following:

Keeping your scheduled follow-up visits

Following a regular exercise program

Following a healthy and balanced diet

Having your tests done as scheduled

Taking all of your medicines as prescribed

Dealing with the side effects of your medicines.

Five-item scale (0–4, very difficult–very easy); maximum score 24, with higher scores denoting easier transplant care.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health OrganizationAdherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for ActionGenevaWHO2003 Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdfAccessed September 12, 2012

- PrendergastMBGastonRSOptimizing medication adherence: an ongoing opportunity to improve outcomes after kidney transplantationClin J Am Soc Nephrol201051305131120448067

- DewMADiMartiniAFDe Vito DabbsARates and risk factors for nonadherence to the medical regimen after adult solid organ transplantationTransplantation20078385887317460556

- SiegalBRGreensteinSMPostrenal transplant compliance from the perspective of African-Americans, Hispanic-Americans, and Anglo-AmericansAdv Ren Replace Ther1997446548996620

- GreensteinSSiegalBCompliance and noncompliance in patients with a functional renal transplant: a multicenter studyTransplantation199866171817269884266

- RaizLRKiltyKHenryMLFergusonRMMedication compliance following renal transplantationTransplantation199968515510428266

- VasquezEMTanziMBenedettiEPollakRMedication noncompliance after kidney transplantationAm J Health Syst Pharm20036066666912701548

- FineRNBeckerYDe GeestSEisenHEttengerRNonadherence consensus conference summary reportAm J Transplant20099354119133930

- DidlakeRHDreyfusKKermanRHvan BurenCTKahanBDPatient noncompliance: a major cause of late graft failure in cyclosporine-treated renal transplantsTransplant Proc198820Suppl 363693291299

- de GeestSBorgermansLGemoetsHIncidence, determinants, and consequences of subclinical noncompliance with immunosuppressive therapy in renal transplant recipientsTransplantation1995593403477871562

- ButlerJARoderickPMulleeMMasonJCPevelerRCFrequency and impact of nonadherence to immunosuppressants after renal transplantation: a systematic reviewTransplantation20047776977615021846

- SellaresJde FreitasDGMengelMUnderstanding the causes of kidney transplant failure: the dominant role of antibody-mediated rejection and nonadherenceAm J Transplant20121238839922081892

- WengFLIsraniAKJoffeMMHoyTGaughanCARace and electronically measured adherence to immunosuppressive medications after deceased donor renal transplantationJ Am Soc Nephrol2005161839184815800121

- O’GradyJGAsderakisABradleyRMultidisciplinary insights into optimizing adherence after solid organ transplantationTransplantation20108962763220124952

- KuypersDRPeetersPCSennesaelJJImproved adherence to tacrolimus once-daily formulation in renal recipients: a randomized controlled trial using electronic monitoringTransplantation20139533333923263559

- MatasAJHalbertRJBarrMLLife satisfaction and adverse effects in renal transplant recipients: a longitudinal analysisClin Transplant20021611312111966781

- ChisholmMALanceCEWilliamsonGMMulloyLLDevelopment and validation of the immunosuppressant therapy adherence instrument (ITAS)Patient Educ Couns200559132016198214

- CukorDRosenthalDSJindalRMBrownCDKimmelPLDepression is an important contributor to low medication adherence in hemodialyzed patients and transplant recipientsKidney Int2009751223122919242502

- SabbatiniMCrispoAPisaniASleep quality in renal transplant patients: a never investigated problemNephrol Dial Transplant20052019419815585511

- WallemacqPGoffinetJSO’MorchoeSMulti-site analytical evaluation of the Abbott ARCHITECT tacrolimus assayTher Drug Monit20093119820419258928

- ChisholmMAMulloyLLDiPiroJTComparing renal transplant patients’ adherence to free cyclosporine and free tacrolimus immunosuppressant therapyClin Transplant200519778315659138

- ChisholmMAVollenweiderLJMulloyLLRenal transplant patient compliance with free immunosuppressive medicationsTransplantation2000701240124411063348

- HilbrandsLBHoitsmaAJKoeneRAMedication compliance after renal transplantationTransplantation1995609149207491693

- Schäfer-KellerPSteigerJBockADenhaerynckKDe GeestSDiagnostic accuracy of measurement methods to assess non-adherence to immunosuppressive drugs in kidney transplant recipientsAm J Transplant2008861662618294158

- KileyDJLamCSPollakRA study of treatment compliance following kidney transplantationTransplantation19935551568420064

- BeckebaumSIacobSSweidDEfficacy, safety, and immunosuppressant adherence in stable liver transplant patients converted from a twice-daily tacrolimus-based regimen to once-daily tacrolimus extended-release formulationTranspl Int20112466667521466596

- DoeschAOMuellerSKonstandinMIncreased adherence after switch from twice daily calcineurin inhibitor based treatment to once daily modified released tacrolimus in heart transplantation: a preexperimental studyTransplant Proc2010424238424221168673

- UrstadKHØyenOAndersenMHMoumTWahlAKThe effect of an educational intervention for renal recipients: a randomized controlled trialClin Transplant201226E246E25322686948

- HougardyJMBroedersNKiandaMConversion from Prograf to Advagraf among kidney transplant recipients results in sustained decrease in tacrolimus exposureTransplantation20119156656921192316

- GuiradoLCantarellCFrancoAEfficacy and safety of conversion from twice-daily to once-daily tacrolimus in a large cohort of stable kidney transplant recipientsAm J Transplant2011111965197121668633