Abstract

Background

The learning preferences of ophthalmology patients were examined.

Methods

Results from a voluntary survey of ophthalmology patients were analyzed for education preferences and for correlation with race, age, and ophthalmic topic.

Results

To learn about eye disease, patients preferred one-on-one sessions with providers as well as printed materials and websites recommended by providers. Patients currently learning from the provider were older (average age 59 years), and patients learning from the Internet (average age 49 years) and family and friends (average age 51 years) were younger. Patients interested in cataracts, glaucoma, macular degeneration, and dry eye were older; patients interested in double vision and glasses were younger. There were racial differences regarding topic preferences, with Black patients most interested in glaucoma (46%), diabetic retinopathy (31%), and cataracts (28%) and White patients most interested in cataracts (22%), glaucoma (22%), and macular degeneration (19%).

Conclusion

Most ophthalmology patients preferred personalized education: one-on-one with their provider or a health educator and materials (printed and electronic) recommended by their provider. Age-related topics were more popular with older patients, and diseases with racial risk factors were more popular with high risk racial groups.

Introduction

Patient-centered care, one of the six domains identified by the Institute of Medicine, includes an informed patient who is an integral member of the care team.Citation1,Citation2 Educating patients about their diagnosis and plan of care is essential in all fields of medicine, including ophthalmology, where lack of patient engagement could result in irreversible blindness. The most common blinding diseases in the United States are macular degeneration, glaucoma, and diabetic eye disease.Citation3 Cataracts are also common but can be cured with surgery.

A Cochrane Review of adherence for glaucoma medicationsCitation4 concluded that education combined with behavioral interventions may improve adherence. Studies that solicited input from patients identified the importance of education in the care of glaucoma and diabetic retinopathyCitation5,Citation6 as well as partnership with patients.Citation7 Not all patient education interventions are useful and effective for individual patients, particularly with respect to health literacy.Citation8

Patient-centered education involves the patient as an adult learner. Principles of adult learning include framing new information on the foundation of the patient’s life experiences and prior knowledge and accommodating diverse learning styles.Citation9 To develop effective patient education interventions and materials and maximally involve the patients in the learning process, we need to understand their learning preferences, specifically in the ophthalmology population of older, possibly visually impaired, adults.

This study examines survey results from ophthalmology patients at a tertiary eye care center. The goal is to better understand the education preferences with respect to learning practices and topics of interest in this population and to guide the development of patient-centered educational interventions and materials targeted to older adults with eye diseases.

Materials and methods

A voluntary two-page survey () was distributed to patients at a tertiary eye care center and satellite clinics during 1 month (May 2012) as part of a quality improvement project to offer patient education lectures to the community on ophthalmology topics. Duke University Institutional Review Board permission was granted to analyze the de identified survey results. The age and racial demographics of the eye center patient population were obtained by querying the Duke University Health SystemCitation10 for comparison with the survey respondents.

The first page included questions about interest in patient education lectures, preferred times and locations, and preferred ophthalmic topics: cataracts, macular degeneration, glaucoma, diabetic eye disease, dry eye, double vision and lazy eye, glasses and contact lenses, low vision rehabilitation, laser vision corrective surgery, droopy eyelids and other cosmetic procedures of the face, and a section to write in other topics. The second page consisted of three questions about learning preferences and a space to write in race and age. The questions were, “What are some of the ways you currently learn about eye health and disease?” “Which of the following would help you to learn about eye health and disease?” “Where do you prefer to learn about eye health and disease?”

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics were summarized with percentages for groups and using means with percentages for ages. A Student’s t-test was used to assess the significance of differences between means. A Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the significance of differences among proportions. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

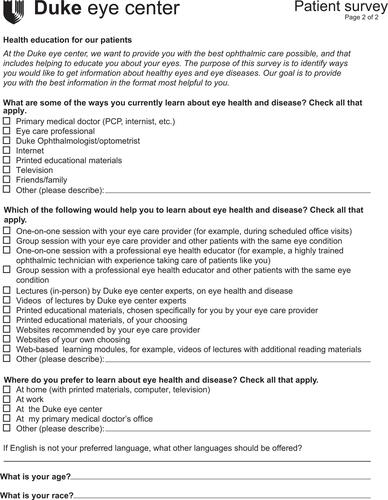

A total of 7,715 patients were seen during the month of survey distribution; 611 surveys (8%) were completed, and 450 respondents indicated their race. There was no significant difference between the sample population and the total population of the patients seen at the eye center with regard to race (). The respondents were younger (average age of 55 years) compared to the total patient population (average age of 59 years, P<0.05).

Figure 1 Racial distribution of the eye center population and the survey respondents.

Preferred learning practices

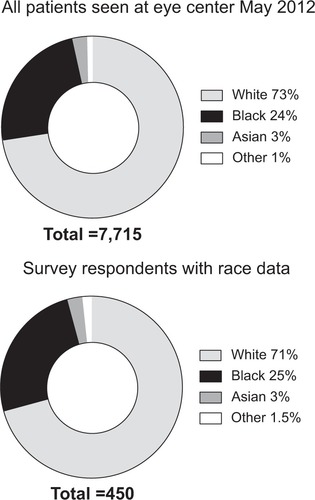

Fifty-five percent of respondents overall preferred one-on-one sessions with eye care providers for learning about eye disease (). Websites (38% of respondents) and printed materials (36%) recommended by the provider were preferred; 29% of respondents like one-on-one sessions with an eye health educator. Respondents noted interest in videos of lectures (14%), web-based modules (12%), in-person lectures (12%), group sessions with providers (12%), self-selected websites (11%), self-selected printed materials (11%), and group sessions with eye health educators (10%).

Figure 2 Preferred learning practices.

One-on-one sessions were favored by older patients (average age of 56 years for those who preferred one-on-one sessions with eye care provider compared with average age 53 for those who did not, P=0.047) (). Web-based learning modules were favored by younger patients (average age 48 years for those who preferred web-based learning modules compared with average age 56 years for those who did not, P=0.001).

Table 1 Preferred learning practice with age and race

Different learning practices were associated with ophthalmic topics of interest and are summarized in . Of note, self-selected websites were not associated with any individual ophthalmic topic.

Table 2 Ophthalmic topics and preferred learning practice

Age and racial demographics of patients interested in ophthalmic topics

Patients with interest in cataracts (average age 61 years), macular degeneration (average age 63 years), glaucoma (average age 59 years), and dry eye (average age 60 years) were older than patients who were not interested in those topics (average age 54 years) (). An interest in double vision (average age 46 years) and glasses and contact lenses (average age 50 years) was associated with younger age.

Table 3 Ophthalmic topics of interest and age

Black patients were more likely to be interested in glaucoma (46% of Black respondents) and diabetic eye disease (31%) compared with other races (). White patients were more likely to be interested in macular degeneration (19% of White respondents, compared with 9% of Black respondents). A higher proportion of Black patients were more likely to be interested in low vision and glasses compared to Whites.

Table 4 Ophthalmic topics of interest and race

Current learning practices

Patients who responded that they learn about eye disease from an eye care professional were older (average age 58, compared to 51 for those not learning from an eye care professional, P<0.001) (). Patients who responded that they use the Internet to learn about eye disease were younger (average age 49, compared to 59 for those not using the Internet, P<0.001). Survey respondents who learn from family and friends were younger (average age 51 compared to 56 for those not learning from family and friends, P=0.012).

Table 5 Current route of eye health information: age and racial characterization

There were racial differences in responses. The majority of White patients (66%) and majority of Black patients (64%) noted that they were currently learning about eye disease from an eye care professional. The numbers of Hispanic and Asian respondents were much lower (ten and eleven respondents, respectively), consistent with the local population.

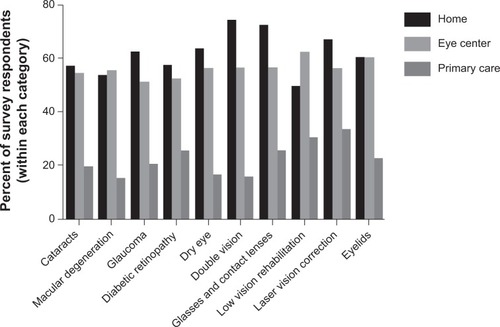

Preferred learning location

Most patients preferred to learn about eye disease either at home or the eye center (). Overall, however, one in five preferred the primary care provider, particularly for learning about low vision rehabilitation and laser vision corrective surgery.

Figure 3 Preferred locations for learning about ophthalmic topics.

Discussion

This study adds to our understanding of educational preferences with respect to learning practices and topics of interest for ophthalmology patients at a tertiary care center.

The survey was voluntary and no compensation was offered; 8% of patients filled out the survey. The demographic comparison with the total patient population suggests that the survey respondents are representative of the ophthalmology patient population with regard to race and age (average age in the sixth decade).

The survey, designed for a quality improvement project, is not a validated research tool. The demographic answers were not verified, nor was it possible to verify whether a diagnosis of interest recorded on the survey corresponded to a patient’s diagnosis. Another limitation of this retrospective study is that patients could select more than one answer for each question; a survey allowing only one answer or a ranking of multiple answers would allow for a more accurate indication of patient preferences. The survey was only offered in English, thus excluding non-English-speaking patients. Patients unable to read due to low vision or low literacy were unlikely to fill out the survey, although accommodations were made for low vision (yellow paper, large font). The education level of the patients was not assessed, limiting the generaliz-ability of the results. The patient population was a tertiary eye care population at a single institution, thus the results may not apply to populations at other types of practices. Also, the low numbers of non-White, non-Black patients were consistent with the local population but suggest that the results may not reflect the preferences of all races.

In this study, we found an association between interest in cataracts and preferred learning practices of eye provider and educator teaching sessions, lectures, videos, and printed materials. This correlation is supported by a study in a Veterans Affairs Health System population of cataract surgery patients. Shukla et alCitation11 found that interventions that included conventional verbal information plus either printed materials at eighth-grade reading levels or a videotape presentation optimized patient understanding of cataract surgery risks/benefits/alternatives. Conversely, we found an association with a preference for lectures and the topics of diabetic retinopathy and cataracts, two common indications for dilated eye exams in older adults. When Owsley et alCitation12 examined the effect of health education sessions on the importance of dilated eye exams for older African American participants, they found no change in dilated eye exam rates before and after the education event. However, they did not assess participant comprehension and learning.

In conclusion, most ophthalmology patients surveyed preferred personalized education interventions, such as one-on-one education sessions, and materials (printed and electronic) recommended by their provider. Age-related topics were more popular with older patients, and diseases with racial risk factors were more popular with high risk racial groups. An enhanced understanding of education preferences could help to develop more effective education interventions and materials for this population of adult learners with eye disease.

With regards to implications for practice, patients with eye disease value printed materials and websites recommended for them by their providers. Primary care locations may consider offering information about low vision rehabilitation and laser vision corrective surgery, as these topics were preferred at primary care locations.

Supplementary material

Disclosure

JAR receives salary support from a K12 career development award from the National Eye Institute. KWM receives salary support from a VA HSR & D career development award. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, Institute of Medicine32001National Academy Press Available from: http://www.nap.edu/books/0309072808/htmlAccessed April 10, 2014

- HahnSRPatient-centered communication to assess and enhance patient adherence to glaucoma medicationOphthalmology200911611 SupplS37S4219837259

- Vision Problems in the US: Prevalence of Adult Vision Impairment and Age-related Eye Disease in AmericaPrevent Blindness America2002 Available from: http://www.usvisionproblems.orgAccessed January 7, 2014

- WatermanHEvansJRGrayTAHensonDHarperRInterventions for improving adherence to ocular hypotensive therapyCochrane Database Syst Rev20134CD00613223633333

- YanXLiuTGruberLHeMCongdonNAttitudes of physicians, patients, and village health workers toward glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy in rural China: a focus group studyArch Ophthalmol2012130676177022801838

- AbueleinenKGEl-MekaweyHSaifYSKhafagyARizkHIEltahlawyEMSociodemographic factors responsible for blindness in diabetic Egyptian patientsClin Ophthalmol201151593159822125407

- KoutroumanosNFolkardAMattocksRBringing together patient and specialists: the first Birdshot DayBr J Ophthalmol201397564865223471821

- MuirKWLeePPHealth literacy and ophthalmic patient educationSurv Ophthalmol201055545445920650503

- CollinsJEducation techniques for lifelong learning: principles of adult learningRadiographics20042451483148915371622

- HorvathMMWinfieldSEvansSSlopekSShangHFerrantiJThe DEDUCE Guided Query tool: providing simplified access to clinical data for research and quality improvementJ Biomed Inform201144226627621130181

- ShuklaANDalyMKLegutkoPInformed consent for cataract surgery: patient understanding of verbal, written, and videotaped informationJ Cataract Refract Surg2012381808422062774

- OwsleyCMcGwinGSearceyKEffect of an eye health education program on older African Americans’ eye care utilization and attitudes about eye careJ Natl Med Assoc20131051697623862298