Abstract

Background

Functional health literacy (FHL) and patient activation can impact diabetes control through enhanced diabetes self-management. Less is known about the combined effect of these characteristics on diabetes outcomes. Using brief, validated measures, we examined the interaction between FHL and patient activation in predicting glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) control among a cohort of multimorbid diabetic patients.

Methods

We administered a survey via mail to 387 diabetic patients with coexisting hypertension and ischemic heart disease who received outpatient care at one regional VA medical center between November 2010 and December 2010. We identified patients with the study conditions using the International Classification of Diseases-Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnoses codes and Current Procedure Terminology (CPT) procedures codes. Surveys were returned by 195 (50.4%) patients. We determined patient activation levels based on participant responses to the 13-item Patient Activation Measure and FHL levels using the single-item screening question, “How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?” We reviewed patient medical records to assess glycemic control. We used multiple logistic regression to examine whether activation and FHL were individually or jointly related to HbA1c control.

Results

Neither patient activation nor FHL was independently related to glycemic control in the unadjusted main effects model; however, the interaction between the two was significantly associated with glycemic control (odds ratio 1.05 [95% confidence interval 1.01–1.09], P=0.02). Controlling for age, illness burden, and number of primary care visits, the combined effect of these measures on glycemic control remained significant (odds ratio 1.05 [95% confidence interval 1.01–1.09], P=0.02).

Conclusion

The interaction between FHL and patient activation is associated with HbA1c control beyond the independent effects of these parameters alone. A personalized approach to diabetes management incorporating these characteristics may increase patient-centered care and improve outcomes for patients with diabetes.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus affects nearly 26 million adults in the United States, with 1.9 million new cases diagnosed annually.Citation1 Many patients with diabetes experience adverse vascular events, including myocardial infarction, peripheral arterial disease, and blindness.Citation2 Diabetes control, characterized by reductions in glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), blood pressure, and cholesterol levels, is directly associated with decreased morbidity and mortality associated with diabetes.Citation3 Diabetes self-management skills, including diet and exercise programs, glycemic monitoring, and adherence to complex medication regimens, contribute to diabetes control and reduction of diabetes-related morbidity.Citation4

Patient activation, ie, involvement in treatment selection, planning, and implementation, is critical for managing diabetes in primary care, as defined by national standards from the American Diabetes Association,Citation5 the Veterans Administration (VA) Department of Defense Management of Diabetes Mellitus Clinical Practice Guidelines,Citation6 and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.Citation7 Patients with lower levels of activation have poorer diabetes self-management and medication adherence than those with higher activation.Citation8,Citation9 Similarly, those with lower levels of functional health literacy (FHL), another patient characteristic associated with the capacity to perform self-management tasks, experience worse diabetes-related outcomes than those with higher FHL levels.Citation10,Citation11 Although the independent effects of FHL and patient activation are well documented, less is known about the combined effect of these two variables on diabetes outcomes. Understanding patients’ FHL and activation levels may guide collaborative goal setting,Citation12 which is an important step for improving blood pressureCitation13 and glycemic controlCitation14 in patients with diabetes. Using brief, validated screening measures, we explored the relationship between FHL, patient activation, and glycemic control in a cohort of multimorbid patients with diabetes receiving care at an established patient-centered medical home in one regional VA medical center.

Materials and methods

Study population

Using International Classification of Diseases-Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes and ICD-9-CM and Current Procedure Terminology codes, we identified patients with coexisting diabetes, hypertension, and ischemic heart disease who received outpatient care between November 10, 2010 and December 8, 2010. Patients were eligible for study participation if they had one inpatient diagnosis code or two outpatient diagnosis codes for each of the study conditions recorded in VA databases and had an identified VA patient-aligned care team, which is the VA model for the patient-centered medical home.Citation15 We also used relevant cardiovascular procedure codes to identify patients with ischemic heart disease. We reviewed each eligible patient’s VA electronic medical record to confirm their disease history. We excluded patients with a documented limited life expectancy,Citation16 those who died during the study period, and those with a diagnosis of dementia within 2 years of the beginning of the study.

Data collection

We mailed to eligible participants an introductory cover letter describing the study along with a self-administered survey that included brief measures of FHLCitation17 and patient activation,Citation18 as well as sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. We also provided a stamped envelope in which to return the survey. To increase the response rate, we remailed the materials once to those who did not return the survey within 4 weeks of the initial mailing. Patients who returned the survey received $20, and we considered them to be enrolled participants. We sent surveys to 387 patients who met the inclusion criteria. From this sample, we received 195 (50.4%) completed surveys. We collected demographic, laboratory, and clinical data from the electronic medical records of all VA patients who met our eligibility requirements and returned valid surveys. We used the Diagnostic Cost Group (DCG) relative risk score, a measure of patient burden of illness, to define clinical complexity.Citation19 The DCG relative risk score is a ratio of the patient’s predicted cost to the average actual cost of the VA population. A score of 1.00 represents the cost of an “average” patient, whereas a DCG relative risk score <1.00 represents a lower-than-average cost (and illness burden), and a score >1.00 represents a higher-than-average illness burden. To assess for nonresponse bias, we compared the sociodemographic characteristics of patients who returned completed surveys with the sociodemographic characteristics of those who did not.Citation20

Main measures

We used a brief, single-item screen for FHL developed by Chew et al.Citation21 Patients who responded “none of the time”, “a little of the time”, or “some of the time” to the question “How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?” were classified as having low FHL. This measure has been validated in patients with diabetesCitation22 and across multiple VA samples with correlations to criterion measures of FHL, including the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine and Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults, short form.Citation17,Citation21 We examined patient activation using the Patient Activation Measure (PAM), which is positively associated with future utilization and diabetes outcomes, including HbA1c levels.Citation9

We determined activation levels based on participant responses to the 13-item PAM survey.Citation18 The survey items assess patients’ skill, confidence, and knowledge with regard to managing issues related to their health care. Responses to each question range from 1 to 4, in ascending order for activation. To determine the overall patient activation score, we calculated the sum of individual responses, which ranged from 13 to 52 among study participants. Participants with a PAM score ≤38 (mean item score <3) were classified as having low activation. PAM scores were normalized, converting the maximum low activation score to 52.9 and the range of scores to 0–100.Citation18 We obtained each patient’s most recent HbA1c reading from his/her medical records. We assessed HbA1c control according to American Diabetes Association guidelines.Citation5

Statistical analyses

We examined associations between glycemic control and patient demographic and clinical characteristics using independent samples Student’s t-tests and chi-square tests. A multiple logistic regression model was used to determine whether activation and FHL (interval-level variables) were individually and/or jointly related to HbA1c control. The main-effects model included only activation and FHL as predictors; whereas the interaction model included these terms, as well as the interaction between activation and FHL. The concordance statistic (c) and the likelihood ratio chi-square value were calculated to assess discrimination and overall goodness of fit of each multivariate model. We conducted a second (adjusted) set of multiple logistic regression models, controlling for any demographic or clinical characteristics significantly associated with HbA1c control. We also included age a priori in the adjusted model, given its clinical importance in determining HbA1c goals. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Among the 195 returned surveys, we included 183 (94%) participants who had complete and valid data for all variables included in these analyses. The mean age of the study cohort was 68 years. Almost one third were nonwhite (28%). Most were married (61%), had significant illness burden (DCG relative risk score of 2.7), and had multiple (4.8 in prior year) primary care visits (). Overall, approximately half (n=90, 49.2%) of the participants had HbA1c levels <7.0%. There was no difference in sociodemographic characteristics (eg, age, sex, and race) between survey responders and nonresponders (all P>0.05, data not shown).

Table 1 Participant demographic and clinical characteristics by HbA1c control

also compares participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics by HbA1c control. Illness burden, as measured by DCG relative risk score, was associated with HbA1c control, with uncontrolled patients having higher illness burden than controlled patients (mean 3.25±3.89 and mean 2.22±2.87, respectively). Similarly, the number of primary care visits was related to HbA1c control, with uncontrolled patients having a greater number of visits than controlled patients (mean 5.75±3.93 and mean 3.88±3.24, respectively). Further, controlled patients reported greater confidence with forms than uncontrolled patients (mean 3.91±1.16 and mean 3.55±1.27, respectively).

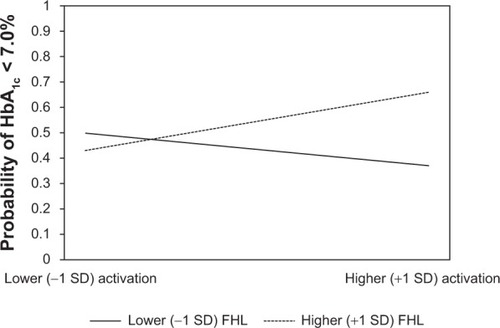

Although neither activation nor FHL was significantly related to glycemic control in the unadjusted main-effects model (likelihood ratio χ2(2)=4.37, P=0.11), the interaction between the two in the complete model was significant (odds ratio 1.05 [95% confidence interval 1.01–1.09], P=0.02; likelihood ratio χ2(3)=10.48, P=0.01), and remained significant in the adjusted model that controlled for age, illness burden, and number of primary care visits (odds ratio 1.05 [95% confidence interval 1.01–1.09], P=0.02, likelihood ratio χ2(6)=21.75, P=0.001) (see ). The interaction is graphed in according to simple slopes. Values are graphed at one standard deviation above and below activation and FHL means. Those with higher activation scores are more likely to have controlled HbA1c, but only when they also have higher FHL.

Figure 1 Simple slopes for the interaction of FHL and patient activation levels on the probability of having an HbA1c level <7%.

Abbreviations: FHL, functional health literacy; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2 Unadjusted and adjusted multiple logistic regression models predicting glycemic controlTable Footnote*

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the relationship between FHL, activation, and HbA1c control among multimorbid patients with diabetes receiving care within an established patient-centered medical home. We found that brief, validated measures of FHL and activation are feasible to obtain among patients within the context of primary care encounters. Further, we found that the combined effect of FHL and patient activation is predictive of better HbA1c control beyond the independent effects of FHL or patient activation alone. These findings persisted after adjusting for age, illness burden, and number of primary care encounters, suggesting that understanding levels of FHL and patient activation may allow better personalization of diabetes self-management interventions, offering a more patient-centered approach to diabetes care.

Self-management interventions often focus on didactic education rather than personalized treatment goals and cultivation of problem-solving skills (action plans).Citation23 Collaborative goal setting is an evidence-based method of engaging patients in diabetes self-management centered on personal goals and action plans.Citation24 We have previously demonstrated that a group-based, primary care intervention to help patients set highly effective, evidence-based diabetes goals had a positive impact on goal-setting ability, diabetes self-efficacy, and HbA1c levels.Citation25,Citation26 Patients who participated in the goal-setting intervention sustained HbA1c improvements for 9 months after the active intervention, in contrast with the typical finding of regression to baseline levels within 4 months after completing traditional diabetes education sessions.Citation27 How ever, in that study, additional improvements in goal-setting quality were not seen when participants returned to routine primary care; and the maintenance of goal-setting activities remained modest at 1 year among intervention participants, suggesting the need to further refine the collaborative goal-setting program.Citation26

Integrating patient-centered characteristics, such as FHL and activation levels, may further personalize the collaborative goal-setting process and improve its long-term effectiveness. Validated, practical measures of FHL and activation levels exist. However, they are often not integrated into routine practice or shown to impact patient outcomes longitudinally. Without brief, validated measures, health care providers frequently have difficulty identifying patients with limited FHL.Citation28,Citation29 Delivering personalized FHL and activation data during patient-clinician encounters may enhance patient-centered communication and decision-making.Citation30 In a study by Seligman et alCitation31 physicians who were notified of the limited FHL in patients with diabetes prior to a visit reported greater use of strategies to improve communication about disease management, but were less satisfied with encounters because of feelings of inadequacy about using FHL information. Importantly, participating physicians received little education about how to use FHL information to guide interactions.Citation31 Therefore, greater awareness and training on how to interpret and integrate measures of FHL and patient activation are needed.

Historically, the primary care visit has not provided an ideal setting to develop or support self-management skills through collaborative goal setting because of time constraints and multiple competing demands.Citation32 However, the transition by many medical practices and health care organizations to the patient-centered medical home model of careCitation15 offers an excellent opportunity to efficiently and effectively integrate diabetes self-management training and support into routine primary care practice.Citation33 With appropriate training, personnel in a patient-centered medical home can use information about patients’ reported FHL and activation levels to personalize goals and action plans within patients’ particular limitations and preferences for involvement.Citation8,Citation34

Despite our important findings, the current study has limitations. Participation in the study was limited to veterans receiving care at one regional VA medical center, which may limit generalizability. In addition, patients receiving care in the VA are overwhelmingly male, and male patients, in general, have been shown to have lower health literacy and patient activation levels than female patients.Citation18,Citation35 Thus, our findings may have differed in a sample with a greater proportion of women. Further, in contrast with prior studies that found independent associations between FHL and activation levels on diabetes outcomes,Citation9,Citation10 we found that only the interaction of these two characteristics was predictive of glycemic control which may reflect differences in the Veteran patient population and may not be representative of all patients with diabetes. Our survey was administered by mail; and, thus, nonresponders may have included a disproportionate number of patients who experience difficulty completing forms, possibly indicating lower levels of health literacy in this group. However, when we compared sociodemographic characteristics of responders with those of nonresponders, we found no significant differences.

Our findings suggest that a personalized approach to diabetes management incorporating patient-centered characteristics, such as FHL and activation levels, may result in more patient-centered care and improved diabetes outcomes. Future research is needed to inform how brief, valid measures of FHL and activation can be incorporated into routine diabetes self-management.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development (VA HSR&D) pilot grant PPO 09-316 (LDW) and the Houston VA HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety (CIN13-413). The authors are grateful to Sylvia Hysong for assistance with development of the survey, and to Tracy Urech and Omolola Adepoju, all of the Houston VA HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety for assistance with manuscript review.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- American Diabetes AssociationData from the 2011 National Diabetes Fact Sheet Available from: http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/statistics/Accessed May 17, 2014

- US Centers for Disease Control and PreventionNational Diabetes Fact Sheet2011 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/DIABETES/pubs/factsheet11.htmAccessed May 17, 2014

- SnowVWeissKBMottur-PilsonCClinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians. The evidence base for tight blood pressure control in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitusAnn Intern Med2003138758759212667031

- NorrisSLLauJSmithSJSchmidCHEngelgauMMSelf-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic controlDiabetes Care20022571159117112087014

- FunnellMMBrownTLChildsBPNational standards for diabetes self-management educationDiabetes Care200932Suppl 1S87S9419118294

- PogachLMBrietzkeSACowanCLDevelopment of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for diabetes: the Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense guidelines initiativeDiabetes Care200427Suppl 2B82B8915113788

- GarberAJAbrahamsonMJBarzilayJIAmerican Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ comprehensive diabetes management algorithm 2013 consensus statement – executive summaryEndocr Pract201319353655723816937

- HibbardJHGreeneJTuslerMImproving the outcomes of disease management by tailoring care to the patient’s level of activationAm J Manag Care200915635336019514801

- RemmersCHibbardJMosenDMWagenfieldMHoyeREJonesCIs patient activation associated with future health outcomes and health care utilization among patients with diabetes?J Ambul Care Manage200932432032719888008

- SchillingerDGrumbachKPietteJAssociation of health literacy with diabetes outcomesJAMA2002288447548212132978

- FransenMPvon WagnerCEssink-BotMLDiabetes self-management in patients with low health literacy: ordering findings from literature in a health literacy frameworkPatient Educ Couns2012881445322196986

- NaikADStreetRLCastilloDAbrahamNSHealth literacy and decision making styles for complex antithrombotic therapy among older multimorbid adultsPatient Educ Couns201185349950421251788

- NaikADKallenMAWalderAStreetRLImproving hypertension control in diabetes mellitus: the effects of collaborative and proactive health communicationCirculation2008117111361136818316489

- HeislerMColeIWeirDKerrEAHaywardRADoes physician communication influence older patients’ diabetes self-management and glycemic control? Results from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS)J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200762121435144218166697

- RoslandAMNelsonKSunHThe patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health AdministrationAm J Manag Care2013197e263e27223919446

- WoodardLDLandrumCRUrechTHProfitJViraniSSPetersenLATreating chronically ill people with diabetes mellitus with limited life expectancy: implications for performance measurementJ Am Geriatr Soc201260219320122260627

- ChewLDBradleyKABoykoEJBrief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacyFam Med200436858859415343421

- HibbardJHMahoneyERStockardJTuslerMDevelopment and testing of a short form of the patient activation measureHealth Serv Res2005406 Pt 11918193016336556

- PetersenLAPietzKWoodardLDByrneMComparison of the predictive validity of diagnosis-based risk adjusters for clinical outcomesMed Care2005431616715626935

- HalbeslebenJRWhitmanMVEvaluating survey quality in health services research: a decision framework for assessing nonresponse biasHealth Serv Res201348391393023046097

- ChewLDGriffinJMPartinMRValidation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient populationJ Gen Intern Med200823556156618335281

- JeppesenKMCoyleJDMiserWFScreening questions to predict limited health literacy: a cross-sectional study of patients with diabetes mellitusAnn Fam Med200971243119139446

- BrownVABartholomewLKNaikADManagement of chronic hypertension in older men: an exploration of patient goal-settingPatient Educ Couns2007691–3939917890042

- Schulman-GreenDJNaikADBradleyEHMcCorkleRBogardusSTGoal setting as a shared decision making strategy among clinicians and their older patientsPatient Educ Couns2006631–214515116406471

- TealCRHaidetPBalasubramanyamASRodriguezENaikADMeasuring the quality of patients’ goals and action plans: development and validation of a novel toolBMC Med Inform Decis Mak20121215223270422

- NaikADPalmerNPetersenNJComparative effectiveness of goal setting in diabetes mellitus group clinics: randomized clinical trialArch Intern Med2011171545345921403042

- GonzalesRHandleyMAImproving glycemic control when “usual” diabetes care is not enoughArch Intern Med2011171221999200021986349

- LindauSTBasuALeitschSAHealth literacy as a predictor of follow-up after an abnormal Pap smear: a prospective studyJ Gen Intern Med200621882983416881942

- BassPFWilsonJFGriffithCHBarnettDRResidents’ ability to identify patients with poor literacy skillsAcad Med200277101039104112377684

- NaikADOn the road to patient centerednessJAMA Intern Med2013173321821923277229

- SeligmanHKWangFFPalaciosJLPhysician notification of their diabetes patients’ limited health literacy. A randomized, controlled trialJ Gen Intern Med200520111001100716307624

- ØstbyeTYarnallKSKrauseKMPollakKIGradisonMMichenerJLIs there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care?Ann Fam Med20053320921415928223

- PietteJDHoltzBBeardAJImproving chronic illness care for veterans within the framework of the Patient-Centered Medical Home: experiences from the Ann Arbor Patient-Aligned Care Team LaboratoryTransl Behav Med20111461562324073085

- SudoreRLLandefeldCSPérez-StableEJBibbins-DomingoKWilliamsBASchillingerDUnraveling the relationship between literacy, language proficiency, and patient-physician communicationPatient Educ Couns200975339840219442478

- GreenbergEJinYUS Department of Education2003National Assessment of Adult Literacy: Public-Use Data File User’s Guide (NCES 2007-464)National Center for Education Statistics2007 Available from: http://nces.ed.gov/naal/pdf/2007464.pdfAccessed May 17, 2014