Abstract

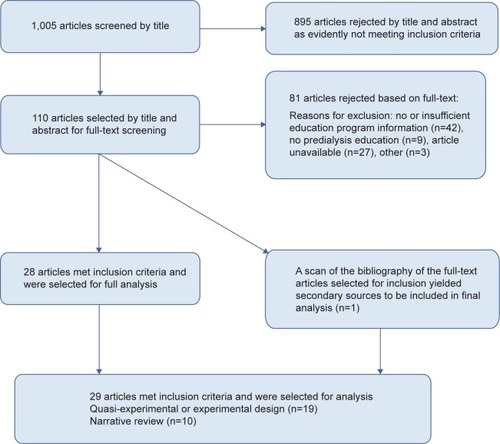

To make an informed decision on renal replacement therapy, patients should receive education about dialysis options in a structured program covering all modalities. Many patients do not receive such education, and there is disparity in the information they receive. This review aims to compile evidence on effective components of predialysis education programs as related to modality choice and outcomes. PubMed MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, and Ovid searches (from January 1, 1995 to December 31, 2013) with the main search terms of “predialysis”, “peritoneal dialysis”, “home dialysis”, “education”, “information”, and “decision” were performed. Of the 1,005 articles returned from the initial search, 110 were given full text reviews as they potentially met inclusion criteria (for example, they included adults or predialysis patients, or the details of an education program were reported). Only 29 out of the 110 studies met inclusion criteria. Ten out of 13 studies using a comparative design, showed an increase in home dialysis choice after predialysis education. Descriptions of the educational process varied and included individual and group education, multidisciplinary intervention, and varying duration and frequency of sessions. Problem-solving group sessions seem to be an effective component for enhancing the proportion of home dialysis choice. Evidence is lacking for many components, such as timing and staff competencies. There is a need for a standardized approach to evaluate the effect of predialysis educational interventions.

Introduction

While in-center hemodialysis (HD) remains the most common treatment modality of end-stage renal disease, home dialysis with peritoneal dialysis (PD), such as automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD, and home HD are treatment options that can provide improved clinical and patient-reported outcomes. In addition, they can be less resource intensive and costly to the health care system.

There are some clinical factors that affect whether an individual patient is clinically suited for PD, but the majority (80%) of end-stage renal disease patients are capable of using home dialysis as their treatment.Citation1

To date, there is no clear evidence that suggests better survival between PD and conventional three-times-per-week in-center HD, although some studies also report that PD is advantageous compared to in-center HD, with higher short-term survival rates and higher quality of life.Citation2–Citation4

All renal replacement therapies have different advantages and disadvantages, which may make them more or less appropriate for the patient depending on his or her clinical and personal situation. PD, which requires learning of technical skills by the patient, also requires a degree of responsibility and capability for self-care. However, it is advantageous in allowing the patient to remain independent, and to have more control over their own treatment and lifestyle. In-center HD is performed by trained nursing staff within a health care setting but can be inconvenient with a rigid schedule of 4 hours treatment plus travel time three times weekly. Most commonly, clinical issues do not limit the treatment selection, and patient preference should be the deciding factor in the selection of treatment modality.Citation5

A growing body of research suggests that early referral to a nephrologist and patient education are associated with increased selection of PD among patients. When patients are presented with predialysis education clearly outlining the different treatment options, they are more likely to select a home dialysis modality.Citation6 However, many patients do not receive predialysis education, and when they do, there is variation in what types of information they receive,Citation7 as well as in the educational methods and system of delivery and support. As a consequence, overall rates of PD use remain much lower than those of in-center dialysis, with a global average of only approximately 11%. In-center HD remains the dominant renal replacement therapy, but the rate of PD varies greatly between countriesCitation8 and between centers within a country.Citation9

The present review aims to review evidence on effective components of predialysis education programs as related to modality choice and selected clinical outcomes. This aids clinical teams in setting up educational processes to ensure patients make informed decisions.

Methods

Identification and screening

PubMed MEDLINE and Ovid databases as well as the Cochrane Library were used to search the academic literature. A tailored search string was defined in order to maximize the number of relevant results. As we were interested in articles specifically addressing the subject of predialysis education, we built the search string in a way that those terms needed to be in the title or abstract of the article: (predialysis[tiab] or pre-dialysis[tiab] or peritoneal dialysis[tiab] or home dialysis[tiab]) and (education[tiab] or information[tiab] or decision[tiab]).

To ensure data was relatively current, a limit was imposed on the search, with inclusion of studies from January 1, 1995 to December 31, 2013. A second limit was added; only papers available in English were accepted. After applying the filters, the total number of search hits returned amounted to 1,005.

Eligibility, inclusion, and exclusion

Regarding the patient group the following inclusion criteria applied:

Adults only (≥18 years old)

Predialysis education for renal replacement therapy for chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients stage III, IV, and V

Planned start patients, unplanned start patients, and patients on dialysis, ie, incident and prevalent patients.

With regard to the information presented on and the structure of the predialysis education programs, articles were only included if the following applied:

A relatively detailed description of the program, such as number and content of sessions, and descriptions of educators

Multiple sessions – a single session education was not considered a “program”

Preferably, a duration greater than 1 month

A multidisciplinary program involving physicians, nurses, dieticians, etc.

Regarding outcomes of the predialysis education, the scope of the literature review was broad. The following outcomes were included, if articles were available:

Dialysis modality choice and the numbers of patients choosing each modality

Any clinical outcome associated with predialysis education

Health-related quality of life

Measures associated with patient choice

Financial impact of patients choosing more home therapies

Patient satisfaction.

The literature was also reviewed for any information on processes, pathways, and organization of the predialysis education programs, such as:

Patient decision making process

Patient identification and enrolment

Content, structure, and methodology of the predialysis education program.

Studies were excluded if the following applied:

The study addressed practical dialysis technique training only (on PD for instance)

Anecdotal stories on treatment option education only

Education materials alone (ie, without process, resources, etc)

CKD patients stage I–II;

Patient support groups only (instead of education program)

Too brief or unclear description of the predialysis education program.

Web search

In addition to the literature searches, a gray literature search was performed using Google. The web search was done on October 19, 2012 with the following search string: (~predialysis and [care or program or education or treatment option]).

Searching in the first ten pages provided relevant information related to CKD educational program. Nineteen links were found to be relevant; information varied between papers, guidelines, annual reports, survey results, web information resources on CKD, web-based program descriptions, and PowerPoint presentations.Citation10–Citation28

Papers were excluded if they were already included in the literature search. An additional search on websites of nephrology and patient association was done. This included the following countries: Finland, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, UK, Canada, USA, Australia, and New Zealand. This search did not deliver data that was sufficiently detailed on the content, structure, and components of educational programs.

Results

Relevant papers

The literature searches yielded 29 relevant studies of which 19 had some sort of (quasi-) experimental design,Citation29–Citation47 and the others were mostly narrative reviews ().Citation7,Citation48–Citation56 The 19 studies were analyzed for effective components of predialysis education programs. Studies with their design and outcomes are summarized in . The Cochrane Library contained no directly relevant systematic reviews.

Table 1 Studies evaluating predialysis education programs: design, outcome, and summary of results

Predialysis education and clinical outcomes

Modality selection

While no quantitative analysis was conducted, studies reported more favorable outcomes for the patients attending a predialysis education program than those patients who did not attend a predialysis education program. Of nine studies reporting on dialysis modality selection using an intervention and control group, six noted a higher proportion of patients selecting home dialysis (PD or another home modality),Citation30,Citation35,Citation38,Citation40,Citation41 while three found no significant difference in modality choice.Citation29,Citation33,Citation36 Four studies with pre-and post- intervention (predialysis education) measurements showed higher levels of home dialysis use after the predialysis education intervention.Citation27,Citation32,Citation44,Citation45

Patient knowledge

Four of 19 quasi-experimental studies reported on measures of patient knowledge. All reported higher levels of knowledge of end-stage renal disease and of different treatment options for patients receiving predialysis education.Citation32,Citation36,Citation40

Mortality and morbidity

Two studies reported on length of hospital stay, which was lower for the education groups (6.5 versus 13.5 total hospital days; 2.2 versus 5.1 hospital days/patient per year).Citation38,Citation57 thus leading to cost savings.Citation36 Eight studies reported on mortality and morbidity (including biochemical indicators, cardiovascular incidents, infection rates, emotional status).Citation31,Citation35,Citation37,Citation46,Citation58,Citation59 All studies reported better rates for the treatment group.

Costs

WatsonCitation47 found a reduction of in-center dialysis from 87% to 33% due to the introduction of an advanced practice nurse with an educating/counseling role. They calculated a theoretical cost saving of $1,328,000 over a 2.5-year period as opposed to the situation without this reduction.

Components of predialysis education programs

The articles retrieved from the literature and gray literature search addressed a wide range of aspects of predialysis education programs.

Multidisciplinary education

Predialysis care is delivered by a multidisciplinary team including, most of the time, a nephrologist, a nurse, a dietician, and a social worker.Citation10,Citation12,Citation14,Citation16,Citation18,Citation19,Citation24,Citation25,Citation27,Citation28,Citation60 A multidisciplinary team can also include: a pharmacist who explains information on the medicines needs;Citation21,Citation22 a psychologist expert, which could be a specialized nurse for emotional support when needed;Citation10,Citation24 a case manager;Citation25 representatives from the local patient kidney support group; and other patients established on maintenance dialysis.Citation27 It is often not clear from the literature whether the members of the multidisciplinary care team are also the main educators for the patient. Of course there will be knowledge transfer during a patient’s visit to a nephrologist or dietitian. It is, however, most of the time not known whether this was in the setting of an educational program with defined cognitive and functional goals.

Seven articles retrieved from the scientific literature review described multidisciplinary education program,Citation29,Citation30,Citation35,Citation36,Citation40,Citation41 which consists of multiple education sessions where patients are educated by three or more health care professionals such as nephrologist, nurse, dietitian, social worker, home-dialysis coordinator, pharmacist, technician, or by other dialysis patients. An Australian survey revealed that although with multidisciplinary education patients are educated by three or more health care professionals, a high proportion of the education is done by the nurse specialist, as nephrologists have limited time for one-on-one education.Citation61 Others see an important role of the nurse as a case manager in planning, implementing, and evaluating educational programs.Citation22

Delivery style

The education delivery style can either be one-on-one sessions or class room teaching style. But in general, a mix of one-on-one and group sessions is advocated. Educational programs should contain individualized one-on-one counseling sessions with a member/members of the multidisciplinary team. This can be a physician, nephrologist, nurse, dietician, social worker, etc.Citation39,Citation41,Citation55 In addition to those small group discussions, peer counseling and problem-solving or “brainstorming” sessions have been described wherein patients discuss treatment modalities, as well as barriers and benefits, and troubleshooting of possible problems with other patients (or facilitators).Citation7,Citation40,Citation41 The group sessions can have a variety of formats such as group lectures, interactive workshops, or open forum sessions.

In the national Australian survey on predialysis education, most participating units combined group and one-on-one sessions. Group education sessions seemed to affect the choice of home dialysis; home dialysis rates increased from 20% to 38%.Citation19

The most ideal design for investigating the effect of certain components of a predialysis education program would be a head-to-head comparison of two programs that differ in a single aspect, while patients are randomly assigned to one of the programs. There was only one study making a head-to-head comparison of two “programs”Citation40 using randomization. In this study, standard care was compared to a group of patients who received standard care plus two-phase education. The standard care consisted of receiving teaching about kidney disease, including dietary instructions, and detailed information about the different modalities of renal replacement therapy. This occurred via an initial 3-hour one-on-one session where patients were seen by a nurse, dietician, and social worker. Patients were then followed by their nephrologist and the multidisciplinary care team every 3–6 months. The two-phase additional education consisted of phase 1, in which patients received four written manuals and a video, and phase 2, which consisted of a 90-minute problem solving group session. The small-group education (phase 2) turned out to be effective in enhancing the proportion of patients choosing self-care dialysis (including home- and self-care HD and PD) from 50% to 82%.

Frequency and duration

The number of sessions and duration per session varies by educational program. There are reports of six individual sessions of 1 hour;Citation14 four sessions, 1 night a week for 2 hours;Citation27 or at least four to five interviews.Citation10 contains a description of the educational programs retrieved from the scientific literature.

Table 2 Summary description of predialysis educational programs evaluated in (quasi-) experimental or observational studies

In the national Australian survey,Citation61 educators were asked to fill out how much time each new patient spends receiving information regarding treatment options. Thirteen percent of units (n=4) spent on average less than 1 hour providing education. Thirteen units were educating for 1–2 hours and 13 units for over 2 hours. The rate of home dialysis was 36% in the units offering the longest education hours (>3 hours) compared to 20% in the units averaging less than 1 hour’s education.

Timing

Timing of education was seen as important to the patient and health care professional, but the studies did not allow firm conclusions to be reached over timing vs dialysis start. The more time a patient has to acquire knowledge prior to commencing dialysis, the better their clinical outcomes and the more likely they are to select a home dialysis modality.Citation56 An estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 30 mL/min (stage IV CKD) has been reported as ideal for referral to CKD clinic.Citation20,Citation21 Others recommend that patients should be referred as early as possible to renal education (>6 months).Citation19

Learning theory

Basing the educational program on the principles of adult learning ensures the appropriateness of delivery of educational materials and content in a manner best understood by this patient populationCitation33 and can help expedite the process of adult learning.Citation7,Citation52 One studyCitation58 tested a new PD home training program based on adult learning theory in a quasi-experimental prospective study using a nonstandardized conventional training group as controls. The adult-learning-based program incorporated the different domains of learning and accommodated different perceptual styles (eg, visual and auditory). The new training program improved patient outcomes (eg, less exit-site infections, less dropout to HD after infection, better fluid balance scores, and better compliance scores). Although this study focused on patients who had already chosen PD, it is a good example of the benefits of a well-designed educational program.

Discussion

Weak evidence base

Unfortunately, the findings presented in the previous section are not based on a strong evidence base since there are a number of limitations found within the studies available for analysis. The study quality was often poor; experimental studies often lacked a control group, as well as pre- and postintervention measures. In some instances, data was presented in comparison to other reports or to previous findings of modality rates rather than in comparison to a control group of patients. Some studies used a quasi-experimental design but did not provide dialysis modality measures, again limiting full analysis.

Two studies reported rates of “self-care dialysis” but neglected to differentiate between home dialysis (PD or home HD) and self-care HD performed in a satellite unit.

There was only one study presenting a head-to-head comparison of educational programs showing that problem- solving group sessions were instrumental in modality choice.Citation40 There were no Cochrane Library systematic reviews that related directly to educational programs for dialysis options. One more-recent Cochrane systematic reviewCitation62 compared studies examining early or late referral to renal units in terms of clinical outcomes including initial dialysis modality. The review did not examine educational programs but did note that studies show early referral results in greater use of PD. The overall better preparation for dialysis in early-referred patients probably relates in part to the education delivered at this time, but the evidence review did not allow for that conclusion.

Need for standardization

Because of the lack of studies comparing detailed components of educational programs, this literature review employed a qualitative rather than quantitative design. The data extraction was conducted with a quasi-systematic method. Keywords and phrases describing content were compared and grouped across studies. However, there is little standardization in the description of intervention (in this case, educational content). For this reason, studies may describe the same content in very different ways or use the same terms to describe very different methods and content. For example, when a program describes a patient’s “case worker”, they could be referring to an individual who meets with the patients to offer support and counseling, but they could also be referring to the role of a health care professional who manages the patient’s interactions between members of the nephrology team (ie, ensuring that the patient is seen by the nephrologist, arranging appointments with dieticians and social workers as needed), or referring to something else entirely. Likewise, many papers do not use educational theory to describe the selection or design of the educational programs. Much of the creation and description of the educational programs and their content is left to the discretion of the study authors, with no standardized method to describe this across the field.

This lack of standardization of education programs is also acknowledged by professionals in the field of predialysis education. The Provincial PD Joint Initiative in Ontario, Canada, acknowledges that standardized predialysis education supports patients in understanding their options but notes there are no recommendations as to its components or content.Citation22

The development of effective interventions is hampered by the absence of a nomenclature to specify and report their content. This limits the possibility of replicating effective interventions, synthesizing evidence, and understanding the causal mechanisms underlying behavior change. In contrast, biomedical interventions are precisely specified (eg, the pharmacological “ingredients” of prescribed drugs, their dose and frequency of administration). For most complex interventions, the precise “ingredients” are unknown; descriptions (eg, “behavioral counseling”) can mean different things to different researchers or implementers. The lack of a method for specifying complex interventions undermines the precision of the methodology to review evidence and synthesise its effectiveness, posing a problem for secondary as well as primary research.Citation63

The UK Medical Research Council’s guidance for developing and evaluating complex interventions acknowledges the need for improved methods of specifying and reporting intervention content. The CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic interventions calls for precise details of the intervention, including a description of the different intervention components.Citation64 For example, this issue of unspecified intervention content is found in other areas of chronic disease, not only renal education programs. For example, researchers have been found to report low confidence in their ability to replicate highly effective interventions for diabetes prevention.Citation63

For the development of a taxonomy of education content and regulations for describing this taxonomy to be developed and promoted in the world of renal education, we could learn from other academic fields, such as a taxonomy of behavior change techniques and the use of theory in behavior change intervention design, which are two models that could be expanded and adapted to the field of predialysis education.Citation65,Citation66

Educating patients about dialysis options is important to allow informed decision making, but clinical evidence is lacking concerning the most effective educational methods and staff competencies to develop the education. There is a need for a standardized approach built on best evidence from CKD and also from other clinical conditions and existing knowledge on the evaluation of complex interventions to ensure formal evaluation of predialysis education programs, and their effects on clinical outcomes and modality choice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Baxter Healthcare SA, Zürich, Switzerland.

Disclosure

Peter A Rutherford was an employee of Baxter Healthcare at the time of performing this research. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MendelssohnDCMujaisSKSorokaSDA prospective evaluation of renal replacement therapy modality eligibilityNephrol Dial Transplant20092455556118755848

- HeafJGLokkegaardHMadsenMInitial survival advantage of peritoneal dialysis relative to haemodialysisNephrol Dial Transplant20021711211711773473

- FentonSSSchaubelDEDesmeulesMHemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis: a comparison of adjusted mortality ratesAm J Kidney Dis1997303343429292560

- MehrotraRMarshDVoneshEPetersVNissensonAPatient education and access of ESRD patients to renal replacement therapies beyond in-center hemodialysisKidney Int20056837839015954930

- CovicABammensBLobbedezTEducating end-stage renal disease patients on dialysis modality selection: clinical advice from the European Renal Best Practice (ERBP) Advisory BoardNephrol Dial Transplant2010251757175920392704

- LudlowMJGeorgeCRHawleyCMHow Australian nephrologists view home dialysis: results of a national surveyNephrology (Carlton)20111644645221518119

- MortonRLHowardKWebsterACSnellingPPatient INformation about Options for Treatment (PINOT): a prospective national study of information given to incident CKD Stage 5 patientsNephrol Dial Transplant2011261266127420819955

- ERA-EDTA RegistryERA-EDTA Registry Annual Report 2011AmsterdamAcademic Medical Center, Department of Medical Informatics2013

- GildJRAFogartyDChapter 1 UK Renal Replacement Therapy Incidence in 2012: UK Renal Registry 16th Annual Report: National and Centre-specific Analyses2013 Availale from: https://www.renalreg.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/01-Chap-01.pdfAccessed 7 Aug, 2015

- AlberghiniEGambirasioMCSarcinaCThe ambiguous concept of predialysis: proposal for a modelG Ital Nefrol2011285541550 Italian22028269

- MarrónBOcañaJCMSalgueiraMAnalysis of patient flow into dialysis: role of education in choice of dialysis modalityPerit Dial Int200525Suppl 3S56S5916048258

- BatesMImproving kidney health and awareness through community based education Available from: http://www.slideshare.net/Sammy17/ckd-educationAccessed 7 August, 2015

- FortnumDMathewTJohnsonKA model for home dialysis, Australia – 2012Kidney Health Australia2012 Available from: http://www.kidney.org.au/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=BfYeuFvtJcI=&tabid=811&mid=1886Accessed 7 August 2015

- GlickmanJChronic Kidney Disease Education Available from: http://ispd.org/NAC/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/CKD-Education-Glickman-April-2011-Notes.pdfAccessed 7 August 2015

- Pre Dialysis Education [webpage on the Internet]CharlestownHunter Renal Resource Centre2012 Available from: http://users.hunterlink.net.au/~mbbjan/pde.htmlAccessed 7 August 2015

- WuIWWangSYHsuKHMultidisciplinary predialysis education decreases the incidence of dialysis and reduces mortality – a controlled cohort study based on the NKF/DOQI guidelinesNephrol Dial Transplant2009243426343319491379

- BernardiniJPriceVFigueiredoAISPD Guidelines/Recommendations; Peritoneal dialysis patient training, 2006Perit Dial Int20062662563217047225

- RohKJoslandEMartinez-SmithYRenal Department Annual Report and Quality Indicators 2011AustraliaSt George Hospital2011 Available from: https://stgrenal.org.au/sites/default/files/upload/Annual-Report-2011.pdfAccessed 7 August 2015

- Kidney Healthy AustraliaTreatment options-teaching patients (including a summary of “Predialysis Education Survey”)2012 Available from: http://homedialysis.org.au/health-professional/educating-patients/treatment-options-teaching-patients/Accessed 7 August 2015

- Kimberly Renal Support Service (KRSS)The Role of Predialysis Coordinator Available from: http://www.kamsc.org.au/renal/downloads/renalpresentations/predialysis_role.pdfAccessed 7 August 2015

- GoldsteinMYassaTDacourisNMcFarlanePMultidisciplinary predialysis care and morbidity and mortality of patients on dialysisAm J Kidney Dis200444470671415384022

- Provincial Peritoneal Dialysis Coordinating CommitteeProvincial Peritoneal Dialysis Joint Initiative: Resource Manual: Detailed Strategy On Increasing Peritoneal Dialysis (PD) Use In OntarioOntarioProvincial Peritoneal Dialysis Coordinating Committee2006 Available from: http://www.renalnetwork.on.ca/common/pages/UserFile.aspx?fileId=100547Accessed 7 August 2015

- WalkerRAbelSMeyerAWhat do New Zealand pre-dialysis nurses believe to be effective care?Nurs Prax N Z2010262

- CrowleySTCKD Series: Improving the Timing and Quality of Predialysis CareWayneTurner White Communications Inc2003 Available from: http://www.turner-white.com/pdf/hp_aug03_care.pdfAccessed 7 August 2015

- Satellite HealthcareSatellite WellBound Offers Superior Patient Education Through its Better LIFE™ Wellness ClassesSan JoseSatellite Healthcare2012 Available from: http://www.satellitehealth.com/medical_community/satellite_wellbound/wellness_classes.phpAccessed 7 August 2015

- The Renal AssociationRA Guidelines – Planning, Initiating and Withdrawal of Renal Replacement TherapyUK2009 Available from: http://www.renal.org/guidelines/modules/planning-initiating-and-withdrawal-of-renal-replacement-therapy#sthash.ZpW4QQaN.dpbsAccessed 7 August 2015

- WilsonVClarkeMPre-Dialysis Education and Care – An Important Factor in ESRD ManagementFresenius Medical Care North America2004 Available from: http://www.advancedrenaleducation.com/Literature/PDServeConnectionPastArticles/PreESRDANecessity/tabid/347/Default.aspxAccessed 7 August 2015

- SpijkensYWJBerkhout-ByrneNCRabelinkTJOptimal predialysis careNDT Plus20081Suppl 4iv7iv1325983991

- AgraharkarMPatlovanyMHenrySBondsBPromoting use of home dialysisAdv Perit Dial20031916316714763055

- ChanouzasDNgKPFallouhBBaharaniJWhat influences patient choice of treatment modality at the pre-dialysis stage?Nephrol Dial Transplant2012271542154721865216

- ChoEJParkHCYoonHBEffect of multidisciplinary pre-dialysis education in advanced chronic kidney disease: Propensity score matched cohort analysisNephrology (Carlton)20121747247922435951

- GómezCGValidoPCeladillaOBernaldo de QuirósAGMojónMValidity of a standard information protocol provided to end-stage renal disease patients and its effect on treatment selectionPerit Dial Int19991947147711379861

- GoovaertsTJadoulMGoffinEInfluence of a pre-dialysis education programme (PDEP) on the mode of renal replacement therapyNephrol Dial Transplant2005201842184715919693

- KingKWittenBBrownJMWhitlockRWWatermanADThe Missouri Kidney Program’s Patient Education Program: a 12-year retrospective analysisNephrol News Issues200822444548525419105516

- KlangBBjörvellHBerglundJSundstedtCClyneNPredialysis patient education: effects on functioning and well-being in uraemic patientsJ Adv Nurs19982836449687128

- KlangBBjörvellHClyneNPredialysis education helps patients choose dialysis modality and increases disease-specific knowledgeJ Adv Nurs19992986987610215978

- LacsonEJrWangWDeVriesCEffects of a nationwide pre-dialysis educational program on modality choice, vascular access, and patient outcomesAm J Kidney Dis20115823524221664016

- LevinALewisMMortiboyPMultidisciplinary predialysis programs: quantification and limitations of their impact on patient outcomes in two Canadian settingsAm J Kidney Dis1997295335409100041

- LittleJIrwinAMarshallTRaynerHSmithSPredicting a patient’s choice of dialysis modality: experience in a United Kingdom renal departmentAm J Kidney Dis20013798198611325680

- MannsBJTaubKVanderstraetenCThe impact of education on chronic kidney disease patients’ plans to initiate dialysis with self-care dialysis: a randomized trialKidney Int2005681777178316164654

- McLaughlinKJonesHVanderstraetenCWhy do patients choose self-care dialysis?Nephrol Dial Transplant2008233972397618577531

- PagelsAAWångMWengströmYThe impact of a nurse-led clinic on self-care ability, disease-specific knowledge, and home dialysis modalityNephrol Nurs J20083524224818649584

- PiccoliGBMezzaEIadarolaAMEducation as a clinical tool for self-dialysisAdv Perit Dial20001618619011045290

- RasgonSAChemleskiBLHoSBenefits of a multidisciplinary predialysis program in maintaining employment among patients on home dialysisAdv Perit Dial1996121321358865887

- RibitschWHaditschBOttoREffects of a pre-dialysis patient education program on the relative frequencies of dialysis modalitiesPerit Dial Int20133336737123547278

- RiouxJPCheemaHBargmanJMWatsonDChanCTEffect of an in-hospital chronic kidney disease education program among patients with unplanned urgent-start dialysisClin J Am Soc Nephrol2011679980421212422

- WatsonDPost-dialysis “pre-dialysis” care: the cart before the horse – advanced practice nurse intervention and impact on modality selectionCANNT J200818303318435361

- BaillodRAHome dialysis: lessons in patient educationPatient Educ Couns19952617247494718

- BalleriniLParisVNosogogy: when the learner is a patient with chronic renal failureKidney Int Suppl2006S122S12617080103

- GolperTPatient education: can it maximize the success of therapy?Nephrol Dial Transplant200116Suppl 7202411590252

- GolperTAMehrotraRSchreiberMSIs Dorothy correct? The role of patient education in promoting home dialysisSemin Dial20132613814223520987

- KeepingLMEnglishLMInformal and incidental learning with patients who use continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysisNephrol Nurs J200128313314319322 discussion 32312143453

- KongILYipILMokGWSetting up a continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis training programPerit Dial Int200323Suppl 2S178S18217986543

- LewisALStablerKAWelchJLPerceived informational needs, problems, or concerns among patients with stage 4 chronic kidney diseaseNephrol Nurs J201037143148 quiz 14920462074

- LuongoMKennedySInterviewing prospective patients for peritoneal dialysis: a five-step approachNephrol Nurs J20043151352015518253

- OwenJEWalkerRJEdgellLImplementation of a pre-dialysis clinical pathway for patients with chronic kidney diseaseInt J Qual Health Care20061814515116396939

- DixonJBordenPKanekoTMSchoolwerthACMultidisciplinary CKD care enhances outcomes at dialysis initiationNephrol Nurs J20113816517121520695

- HallGBoganADreisSNew directions in peritoneal dialysis patient trainingNephrol Nurs J20043114915415916315114797

- SouqiyyehMZAl-WakeelJAl-HarbiAEffectiveness of a separate training center for peritoneal dialysis patientsSaudi J Kidney Dis Transpl20081957458218580016

- WautersJPLameireNDavisonARitzEWhy patients with progressing kidney disease are referred late to the nephrologist: on causes and proposals for improvementNephrol Dial Transplant20052049049615735240

- D. F. Pre-dialysis education – A National Australian Survey (Jan 2012)2012 Available from: http://www.kidney.org.au/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=4u5Qky3opAc%3D&tabid=635&mid=1590Accessed 7 August 2015

- SmartNADiebergGLadhaniMTitusTEarly referral to specialist nephrology services for preventing the progression to end-stage kidney diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20146CD00733324938824

- MichieSAbrahamCEcclesMPFrancisJJHardemanWJohnstonMStrengthening evaluation and implementation by specifying components of behaviour change interventions: a study protocolImplement Sci201161021299860

- BoutronIMoherDAltmanDGSchulzKFRavaudPCONSORT GroupExtending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaborationAnn Intern Med200814829530918283207

- MichieSPrestwichAAre interventions theory-based? Development of a theory coding schemeHealth Psychol2010291820063930

- AbrahamCMichieSA taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventionsHealth Psychol20082737938718624603

- AntonovskyAThe salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotionHealth Promotional Int19961111118