Abstract

Background

Older patients often experience the burden of multiple health problems. Physicians need to consider them to arrive at a holistic treatment plan. Yet, it has not been systematically investigated as to which personal burdens ensue from certain health conditions.

Objective

The objective of this study is to examine older patients’ perceived burden of their health problems.

Patients and methods

The study presents a cross-sectional analysis in 74 German general practices; 836 patients, 72 years and older (mean 79±4.4), rated the burden of each health problem disclosed by a comprehensive geriatric assessment. Patients rated each burden using three components: importance, emotional impact, and impact on daily activities. Cluster analyses were performed to define patterns in the rating of these components of burden. In a multilevel logistic regression analysis, independent factors that predict high and low burden were explored.

Results

Patients had a median of eleven health problems and rated the burden of altogether 8,900 health problems. Four clusters provided a good clustering structure. Two clusters describe a high burden, and a further two, a low burden. Patients attributed a high burden to social and psychological health problems (especially being a caregiver: odds ratio [OR] 10.4, 95% confidence interval [CI] 4.4–24.4), to specific symptoms (eg, claudication: OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.3–4.0; pain: OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.6–3.1), and physical disabilities. Patients rated a comparatively low burden for most of their medical findings, for cognitive impairment, and lifestyle issues (eg, hypertension: OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.2–0.3).

Conclusion

The patients experienced a relatively greater burden for physical disabilities, mood, or social issues than for diseases themselves. Physicians should interpret these burdens in the individual context and consider them in their treatment planning.

Introduction

Patients’ perceived burdens of their health problems play an important role in the consultation. Information gathering of these perceptions is considered as part of the “groundwork for explanation and treatment planning”.Citation1 Older patients, however, often do not present with just one but multiple morbidities. Rather than deciding upon treatment for a single condition, doctors need to factor multiple health problems into one holistic treatment plan.Citation2 In these circumstances, patients’ views on their disease-specific burdens need to be simultaneously collected and weighed in relation to one another.Citation3,Citation4 In practice, however, physicians gather views on single diseases in a subsequent way,Citation5 and there is no clear strategy on how to strike a balance between different health-related burdens.

The phrase “burden” is introduced in this context to depict illness perceptions associated with negative impacts of a health problem. The underlying concept of illness perceptions used here is Leventhal’s common-sense model of illness representation. In this model, the individual is seen as a problem solver, who evaluates a health problem on the cognitive and emotional level. The cognitive themes center around the disease label, its perceived timeframe, causal attributes, controllability, and consequences. In parallel, emotional responses gain momentum with feelings such as depression, annoyance, anger, or anxiety.Citation6 Hence, the perceived burden of a health problem is influenced by personal emotional and cognitive appraisals, both of which need to be represented in an assessment of burden.

Perceived burden is usually assessed using two common approaches: generic measures across diseases or measures for specific conditions. An example of a generic measure is self-rated health. Population studies demonstrate a general decrease in self-rated health with advanced age and the presence of diseases.Citation7 Other instruments measure burden for a specific condition or context, such as claudication or the caregiver’s burden.Citation8,Citation9 Both approaches cannot be applied to assess burdens of multiple health problems within a person, and instruments that measure or rank multiple burdens are not yet established. A good platform to develop such an assessment of multiple burdens seems to be the Duke/WONCA Severity of Illness Checklist. The original version assesses the severity of health problems for a patient from a professional point of view. A modified version was developed later to capture the patient’s perspectives on his or her health problems.Citation10 We chose this patient version to measure perceived burden, and pilot tested and revised it in an earlier study.Citation11

The negative impact of multiple morbidities on health-related quality of life has implications for clinical practice.Citation12 Care decisions cannot be solely justified by guidelines for single diseases. Rather, patient-related burdens and treatment preferences need to be factored into the complex decision-making process.Citation13 However, there appears to be a research gap in surveying and understanding the differential burden for patients with multimorbidity. The current study aims to examine perceived burdens of older patients of their different health problems.

Methods

Research setting and ethics approval

Data were derived from a subproject of the prerequisites for a new health care model for elderly people with multimorbidity (PRISCUS) consortium, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. The subproject is a multicenter-controlled intervention trial in German general practices that took place between 2008 and 2010 (DRKS 00000575).Citation14 The aim was to examine whether a doctor–patient consultation following a geriatric assessment improves the perceived burden of health problems in older patients. In this paper, we utilize the baseline data only. At baseline, all study participants received a comprehensive geriatric assessment (STEP, see “Data collection on patients’ health problems and their perceived burden for each problem”) and rated the perceived burden for each disclosed health problem. The type of health problem was then associated with its perceived burden. The ethics committee of Hannover Medical School approved of the study (number 4991).

Recruitment

For the PRISCUS project, we recruited 56 family physicians and added these to 18 family physicians from an existing epidemiological cohort (get-abi-cohort).Citation15 The 56 family physicians were enrolled by accessing regional lists of the Association of Statutory Health Insurance Registered Doctors and of the teaching family practices. The practices covered altogether five regions in Germany (Hannover, Marburg, Munich, Leipzig, and Witten-Herdecke). Patients were enrolled in the practices if they fulfilled the inclusion criteria and consented to the study procedures. Inclusion criteria were the following: age 72 years and older (minimum age of the get-abi patient cohort), should be able to visit the practice, and should be contactable by telephone. Exclusion criteria were inability to consent, severe hearing or understanding difficulty, and simultaneous participation in another study.

Data collection on patients’ health problems and their perceived burden for each problem

Participants received a comprehensive geriatric assessment “STEP” performed by study nurses in the practices. STEP is an assessment used in primary care studies in Germany and neighboring countries.Citation16 It addresses health problems, risks, and health behaviors of seven different health domains: functional health, social circumstances, somatic symptoms, medical findings, mood, preventive lifestyle issues, and cognition. It contains 44 items, in the form of questions and a few simple examinations, such as taking the pulse and blood pressure, a clock-drawing test to screen cognition, a timed-up-and-go test for mobility and risk of falls, and a foot examination.Citation17 Immediately after the assessment, patients received a list of their individual health problems. Our study nurses then collected ratings of the perceived burden for each listed problem.

Operationalization of patient-rated burden

The assessment of the perceived burden for each problem was based on the Duke Severity of Illness Checklist modified by Okkes et al for patient self-assessment.Citation10 Results from our pilot study led us to determine three items, which best capture different aspects of burden using the cognitive component of significance, a disabling, and an emotional component.Citation11

“How important is this problem to you?”

“How much are you emotionally affected by the problem?”

“How much does this problem limit you in your daily activities?”

Responses were on a four-point Likert scale: “not at all”, “a little”, “fairly”, and “very”. This even-numbered scale is used to produce a forced choice with no indifferent option available. Such a scale decreases social desirability bias and makes it easier to dichotomize responses for analysis.Citation18

The three questions were applied to 34 out of 44 health problems in the STEP assessment (triple ratings). For nine STEP problems, however, it did not make sense to inquire about resulting limitations in daily activities. In these cases, patients only responded to the remaining two burden components (dual ratings). For example, it is meaningless to ask “How much are you limited in your daily activities?” for a health problem like “I have no person to trust”. For the same reason, patients were asked to rate “unknown or no vaccination coverage” just according to its perceived importance. In , the 44 health problems are presented together with the type of burden rating (34 triple, nine dual, one single rating).

Table 1 Health problems disclosed by the STEP assessment: prevalence of problems and type of patient burden ratings

Data analyses

The data of 826 patients were analyzed. Altogether, they had 9,572 health problems disclosed by the assessment, of which they rated 8,900 according to the perceived burden.

We first determined the prevalence of health problems () and the separate relative frequencies of perceived importance, emotional affection, and limitation in daily activities for each health problem. In a next step, we considered the combined burden components of a health problem (dual or rather triple ratings) and explored their response combinations. For this reason, the robust clustering method, partitioning around medoids, from Kaufman and Rousseeuw was applied to the response items to identify groups of similar patterns (clusters).Citation19 The term medoid refers to a representative data object within a cluster for which the distance to all the other members of the cluster is minimum. The average silhouette width provides a measure of cluster goodness and shows how close each data object is to its medoid and how distant to the neighboring medoid. A large average silhouette width (approximating 1) means that the entered data objects are well clustered; a value of −1 means that data are poorly clustered.

Two cluster analyses were performed, one for the triple ratings of burden and one for the dual ratings. For health problems with triple ratings, four clusters provided the best average silhouette width (clusters A0, A1, A2, A3); for health problems with dual ratings, it was three clusters (clusters B0, B1, B2; ). The clusters A0 and B0, A1 and B1, and A2 and B2 turned out to convey the same message (as shown in ). Therefore, we felt it was justified to merge the clusters for further analysis: A0 and B0→0, A1 and B1→1, A2 and B2→2, and A3→3.

Table 2 Assignment of patient ratings into clusters

To further evaluate the influence of different covariates (eg, age, sex, type of health problem) on these clusters, a multilevel (mixed-effect) logistic regression was applied. As several health problems belong to one patient, the patient entered as random effect into this model. The clusters were used as the outcome variable in the regression model. Clusters “2” and “3” were defined as presenting a high burden because they reveal a negative impact on emotions and/or on daily activities. Clusters “0” and “1” express a lower burden with no such consequences. As predictor variables we used patient’s characteristics (age ≥80/<80 years, sex, education status [low: elementary school or less]), number of health problems [having ≥11/<11, 11 being the median for this population], and type of health problem. There were 44 types of health problems for which sleeplessness was used as the reference value. Sleeplessness was chosen as a reference because it holds the middle position in the cluster ratings of burden (49% of affected patients rated a high burden, 51% a low burden).

We used the following statistical programs for our analyses: SPSS Version 22 for the descriptive analyses, R package “cluster” for the cluster analyses, and STATA Version 12 for the multilevel logistic regression analysis.

Results

Participants

Seventy-four physicians from five German regions took part in the study. In their practices, a total of 836 patients agreed to participate. Four patients did not match entry criteria. Another six patients had participated in the assessment but not in the burden ratings and were excluded. The remaining 826 patients were on average 79 (±4.4) years old, 61% were female, and 41% lived alone, 56% with a partner, 2% with their children, and less than 1% in institutional care. The 826 patients had altogether 9,572 health problems disclosed by the STEP assessment with a median of eleven problems (interquartile range 8–15). Participants rated the burden for 8,900 of the problems, and 672 problems (7%) were not rated. presents the prevalence of the 44 health problems and the burden ratings disclosed by the assessment.

Clusters of burden

Two cluster analyses (one for the triple ratings and one for the dual ratings) were performed to identify groups of cases, which are similar with regard to their response patterns. Results are shown in . An optimal clustering structure was reached with four clusters for the triple ratings (A0–A3), and with three clusters for the dual ratings (B0–B2) as determined by silhouette width.

Of practical significance is a common hierarchy of patient perceptions: whenever patients perceived a problem as limiting in daily activities, they also felt emotionally affected and considered it important. Likewise, whenever patients perceived a problem as emotionally affecting but not limiting in activities, they also considered it important. Important health problems could also stand for themselves. These dependencies were responsible for the confined set of clusters and the good clustering structure.

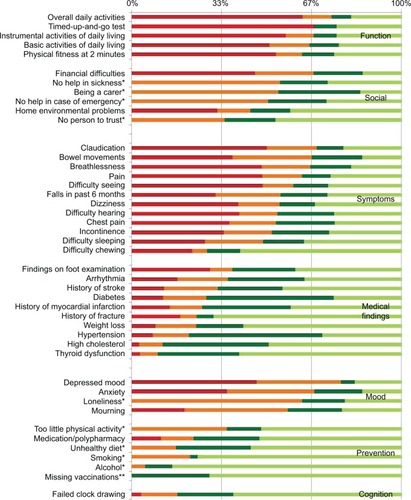

Health problems and their assignment to burden clusters

depicts the 44 health problems with their associated perceived burden clusters. They are listed within the seven health domains. The stacked bars for each health problem represent the proportion of patients, whose associated burden was allocated to clusters 3, 2, 1, and 0.

Figure 1 Proportions of burden clusters (“0”, “1”, “2”, “3”) for each health problem.

Cluster “3”: high burden, which is important, emotionally affecting, and limiting in daily activities.

More than half of the patients within the domain of functional health problems, such as difficulties with basic and instrumental activities of daily living or with a slow walk (failed timed-up-and-go test), perceived such a high burden. Also, patients who suffered from symptoms of claudication, shortness of breath, pain, and difficulty seeing perceived these problems as burdensome in this way.

Cluster “2”: high burden, which is important and emotionally affecting with no impact on daily activities.

Social problems, such as being a caregiver, the absence of a close person, and problems with mood, predominately fell into this category.

Cluster “1”: low burden, which is important with no impact on emotions or daily activities.

This was the case for some medical findings, such as hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol levels, thyroid dysfunction, and history of myocardial infarction.

Cluster “0”: low burden, which is unimportant with no impact on emotions or on daily activities.

Patients predominately considered their unhealthy lifestyles in the preventive health domain as not burdensome but also history of a fracture and a failed clock-drawing test used for dementia screening.

Influence of patient characteristics and specific health problems on high-burden clusters

The multilevel logistic regression analysis enabled us to explore the independent effect of different health problems on the perceived burden (outcome variable represented by high-burden clusters “2 and 3”; ). In this prediction model, adjustments were made for patient characteristics and burden ratings within a patient (level 1) and burden ratings between patients (level 2). Patients with greater than or equal to eleven health problems (median in this population) had a greater chance of experiencing a high burden for any of their problems as compared to patients with fewer health problems.

Table 3 Multilevel logistic regression model: predictors of a perceived high burden

The 44 specific health problems were also taken into account with sleeplessness used as the reference. Compared to patients who suffered from sleeplessness, most of the functional and social health problems predicted a higher burden; this also applied to some symptoms, such as pain, claudication, shortness of breath, and difficulty with bowel movements. Additionally, depression and loneliness were considered to be highly burdensome. By far, the greatest chance of being rated as a high burden was the caregiving role.

By contrast, a relatively low burden was present for all medical findings with the exception of history of falls. Patients also considered problems with chewing, vaccination, the clock-drawing test, and some preventive lifestyle issues, such as problems with medication, smoking, and alcohol abuse, as hardly burdensome (). High cholesterol levels and thyroid dysfunction had by far the greatest chance of receiving a low burden.

Discussion

In this study, older patients rated the burden for each of their health problems. Three components were used to portray burden: importance, emotional impact, and impact on daily activities. The study generates three main findings. Firstly, the clusters obtained from the three components indicate a hierarchy of burden, in that “impact on daily activities” is always accompanied by “emotional impact”, and “emotional impact” is always accompanied by “importance”. “Importance”, however, can appear alone. Secondly, the perceived burden differs in its nature and extent depending on the underlying health problem: “non-diseases”, such as functional health problems, psychological issues, social circumstances, and some symptoms are related to a high burden with an impact on daily living and on emotions. Other problems, in particular, chronic diseases and preventive lifestyle issues, are associated with a lower burden. Thirdly, the multilevel regression analysis shows that additional factors such as the presence of many health problems and financial difficulties independently predict high burden.

Attributes of the burden components (limitations on daily living, affection, and importance)

Patients rating clusters of burden demonstrated a hierarchy. The component “limitations in daily activities” always also involved negative affections and an appreciation of importance. Previous studies have shown that the experience of functional limitations has an independent negative effect on self-rated health.Citation20,Citation21 This indicates that it is an own entity within the patient perception of health. What the experience of being limited in daily activities actually entails remains fairly unclear. However, it has been previously shown that it is linked to negative emotions, such as distress and depression, but aspects such as experiencing dependence or losing autonomy also play a role.Citation22–Citation24

Another component of burden is emotion. In the current study, a large proportion of patients felt emotionally burdened if they were affected by mood disorders or by social stressors, such as lack of support or isolation. A recent study has shown that little social participation has a direct effect on psychological distress.Citation25

The third burden component deals with the notion of importance. In our study, patients frequently perceived medical findings (eg, high cholesterol levels, diabetes, and hypertension) important but rarely disabling or emotionally affecting. Similar observations have been made in previous quality-of-life studies for hypertension and diabetes.Citation26,Citation27 Possible explanations are that older patients may not be fully aware of the diagnosis and its consequences and are less likely to take control.Citation28 They may perceive those diseases just as labels and not relate them to disease-specific symptoms and experiences, or patients blindly trust their doctors’ treatment and risk management.Citation29 It may be exactly these aspects of dissociation and handing control over to professionals that move responsibilities to the physicians. This, in turn, relieves patients from their perceived burden.Citation30

Single health problems and their perceived burden in relation to each other

Previous research dealt with subjective health and related concepts either using a holistic measure across diseases or focusing on a single disease. We deliberately wanted patients with multiple health problems to self-assess their burden for each problem in the context of all their problems.

The majority of our study patients associate problems in the health domains of mood and function with a high burden (with an emotional and/or disabling impact). These links have been previously made in studies of self-rated health, yet they have found insufficient attention in practice.Citation31,Citation32 Disease-specific recommendations giving guidance on controlling the underlying disorder take center stage, while professional attention on the resultant disability or handicap falls behind.Citation33,Citation34 Presently, studies are underway to determine effects of new health care programs to assess and prevent disability in older patients in general practices.Citation35,Citation36

In our study, patients also rated several symptoms as highly burdensome, in particular pain, problems with bowel movements, and shortness of breath. Despite their perceived burden, these often remain underdiagnosed in practice, and in the case of problems with bowel movements, patients do not experience sufficient treatment relief.Citation16,Citation37–Citation39

A comparatively low burden was connected with health problems, such as chronic diseases and especially preventive lifestyle issues (eg, unhealthy diet or lack of physical activity). Patients may have found lifestyle issues relatively insignificant in the light of other health problems; they may also have considered the additional burden that comes with efforts toward behavioral change. Interestingly, also the failed clock-drawing test had little effect on the perceived burden. Patients may have felt awkward with their test performance and may have denied any personal implications.

Additional findings from the multilevel regression analysis

In the regression model, being a caregiver turned out to be the most relevant predictor of a high burden. It is well known that caring interferes with many health and life domains,Citation40 and the risk of hospitalization and mortality rises with an increasing burden of caregiving.Citation41 Family physicians tend to underrate the impaired health of caregivers and often feel unable to provide services tailored toward their special needs.Citation42

The regression model also reveals a significant association of a high burden with a low income but not with sex, age, and education. Recent regression models on older people’s or patients’ self-rated health also found no association between burden and sex, and differing effects for income, education, and age.Citation43–Citation45 In accordance with the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam, our model demonstrates that the presence of multiple health problems has an independent effect on burden.Citation46

Strengths and limitations

Our study moves to the fore the subjective perceptions of older patients on their multiple health problems facilitating a differentiated picture on the associated burdens. We have also tested a practical and easy method that assesses the burden of health problems in patients with multimorbidity.

There are some limitations in the measurement and interpretation of burden. The perceived burden as such is not an established concept, and we do not presume to provide a comprehensive understanding of burden. It is possible that through the structured nature of the study instrument, we did not capture all meanings of burden. We also assigned a “high” or “low” burden to the response combinations, which is an interpretative statement. Hence, further theoretical and empirical research is needed as well as a formal validation of instruments. The findings may not be representative for the general population. As patients were directly recruited from practices, they may have perceived their health problems more severely. Our data on burden result from a cross-sectional study. This “snapshot” cannot capture different perception stages that patients may adopt in the course of their diseases.

The STEP assessment does not deal with all health problems that older people encounter. However, it has been specially developed to give a comprehensive overview of typical old-age problems representing symptoms, disabilities, and health-related environmental factors that are often excluded in studies examining subjective health perceptions.

Conclusion

Older patients have a wide spectrum of health problems and rate the burden associated with these quite differently. Functional and psychological problems, adverse social circumstances, and some specific symptoms induce a great and comprehensive burden. Also, the presence of multiple health problems and financial difficulties add to this burden. Other health problems, such as lifestyle issues and chronic diseases, generate a relatively low burden. Underlying reasons are hypothetical and need to be investigated further.

It has been commented that with an emphasis on disease-specific evidence-based medicine, “the relief of suffering as a goal of medicine” moves into the background.Citation47 Family physicians are the primary contacts for older patients who suffer in particular from functional, psychological, and social health problems. Our findings may encourage physicians to actively inquire into older patients’ perceived burdens and use this information as an additional factor in weighing up treatment decisions in the presence of multimorbidity.Citation48

Author contributions

UJW initiated this study, analyzed the results, and wrote the paper. RKM was responsible for data management. BW conducted the data analyses. GT und CM oversaw the fieldwork and data collection. EHP oversaw the whole project. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the family physicians who participated in this study. They also thank Prof Dr med Stefan Wilm and his team from the Institute of General Practice, Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf, who recruited general practices in the Witten-Herdecke region. Further participating partners in the PRISCUS project are HJ Trampisch, L Pientka, U Thiem, P Thürmann, P Platen, K Berger, and W Greiner. The project was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research [01ET0722].

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SilvermanJKurtzSDraperJSkills for Communicating with PatientsOxfordRadcliffe Publishing200466

- TinettiMEMcAvayGJChangSSContribution of multiple chronic conditions to universal health outcomesJ Am Geriatr Soc2011591686169121883118

- BaylissEBosworthHNoelPWolffJLDamushTMMciverLSupporting self-management for patients with complex medical needsChronic Illn2007316717518083671

- FraenkelLMcGrawSParticipation in medical decision making: the patients’ perspectiveMed Decis Making20072753353817873253

- AnthierensSTansensAPetrovicMChristiaensTQualitative insights into general practitioners views on polypharmacyBMC Fam Pract2010116520840795

- DiefenbachMLeventhalHThe common-sense model of illness representation: theoretical and practical considerationsJ Soc Distress Homel199651137

- IdlerEBenyaminiYSelf-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studiesJ Health Soc Behav19973821379097506

- NordanstigJKarlssonJPetterssonMWann-HanssonCPsychometric properties of the disease-specific health-related quality of life instrument VascuQoL in a Swedish settingHealth Qual Life Out20121045

- DeekenJFTaylorKLManganPYabroffKRInghamJMCare for the caregivers: a review of self-report instruments developed to measure the burden, needs, and quality of life of informal caregiversJ Pain Symptom Manage20032692295314527761

- OkkesIMVeldhuisMLambertsHSeverity of episodes of care assessed by family physicians and patients: the DUSOI/WONDA as an extension of the international classification of primary care (ICPC)Fam Pract20021935035612110553

- Junius-WalkerUStolbergDSteinkePTheileGHummers-PradierEDierksMLHealth and treatment priorities of older patients and their general practitioners: a cross-sectional studyQual Prim Care201119677621575329

- BrettschneiderCLeichtHBickelHMultiCare Study GroupRelative impact of multimorbid chronic conditions on health-related quality of life – results from the MultiCare Cohort StudyPLoS One20138e6674223826124

- BoydCMFortinMFuture of multimorbidity research: how should understanding of multimorbidity inform health system design?Public Health Rev201032451474

- ThiemUHinrichsTMüllerCAPrerequisites for a new health care model for elderly people with multiple morbidities: results and conclusions from 3 years of research in the PRISCUS consortiumZ Gerontol Geriat201144suppl 2101112

- The getABI Study GroupThe German epidemiological trial on Ankle Brachial Index (getABI): rationale, design and methodsVASA20024241248

- PiccolioriGGerolimonEAbholzHGeriatric assessment in general practice using a screening instrument: is it worth the effort? Results of a South Tyrol StudyAge Ageing20083764765218703519

- SandholzerHHellenbrandWv Renteln-KruseWvan WeelCWalkerPThe Step-PanelAn evidence-based approach to assessing older people in primary careOcc Paper R Coll Gen Pract200282153

- GarlandRThe mid-point on a rating scale: is it desirable?Mark Bull199126670 Research Note 3

- KaufmanLRousseeuwPJFinding Groups in DataNew JerseyWiley and Sons2005

- ArnadottirSAGunnarsdottirEDStenlundHLundin-OlssonLDeterminants of self-rated health in old age: a population-based, cross-sectional study using the international classification of functioningBMC Public Health20111167021867517

- GalenkampHBraamAWHuismanMDeegDJSeventeen-year time trend in poor self-rated health in older adults: changing contributions of chronic diseases and disabilityEur J Public Health20132351151722490472

- CairneyJFaulknerGVeldhuizeSWadeTChanges over time in physical activity and psychological distress among older adultsCan J Psychiatry20095416016919321020

- van den BrinkCLTijhuisMvan den BosGAGiampaoliSNissinenAKromhoutDThe contribution of self-rated health and depressive symptoms to disability severity as a predictor of 10-year mortality in European elderly menAm J Pub Health2005952029203416195527

- BretonÉBeloinFFortinCGender-specific associations between functional autonomy and physical capacities in independent older adults: results from the NuAge studyArch Gerontol Geriatr201458566223978329

- BoenHDalgardOBjertnessEThe importance of social support in the associations between psychological distress and somatic health problems and socio-economic factors among older adults living at home: a cross-sectional studyBMC Geriatr2012122722682023

- AlonsoJFerrerMGandekBIQOLA Project GroupHealth-related quality of life associated with chronic conditions in eight countries: results from the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) ProjectQual Life Res20041328329815085901

- WangHMBeyerMGensichenJGerlachFMHealth-related quality of life among general practice patients with differing chronic diseases in Germany: cross sectional surveyBMC Public Health2008824618638419

- OstchegaYDillonCFHughesJPCarrollMYoonSTrends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in older U.S. adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1988 and 2004J Am Geriatr Soc2007551056106517608879

- Perret-GuillaumeCGenetCHerrmannFBenetosAHurstSAVischerUMAttitudes and approaches to decision making about antihypertensive treatment in elderly patientsJ Am Med Dir Assoc20111212112821266288

- Junius-WalkerUWredeJSchleefTWhat is important, what needs treating? How GPs perceive older patients’ multiple health problems: a mixed method research studyBMC Res Notes2012544322897907

- MulsantBAnguliMSeabergEThe relationship between self-rated health and depressive symptoms in an epidemiological sample of community-dwelling older adultsJ Am Geriatr Soc1997459549589256848

- SchüzBWurmSSchöllgenITesch-RömerCWhat do people include when they self-rate their health? Differential associations according to health status in community-dwelling older adultsQual Life Res2011201573158021528378

- SmithSO’DowdTChronic diseases: what happens when they come in multiples?Br J Gen Pract20075726827017394728

- BounthavongMLawAVIdentifying health-related quality of life (HRQL) domains for multiple chronic conditions (diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia): patient and provider perspectivesJ Eval Clin Pract2008141002101118759755

- SuijkerJJBuurmanBMter RietGComprehensive geriatric assessment, multifactorial interventions and nurse-led care coordination to prevent functional decline in community-dwelling older persons: protocol of a cluster randomized trialBMC Health Serv Res2012128522462516

- StijnenMMDuimel-PeetersIGJansenMWVrijhoefHJEarly detection of health problems in potentially frail community-dwelling older people by general practices – project [G]OLD: design of a longitudinal, quasi-experimental studyBMC Geriatr201313723331486

- WatkinsEWollanPCMeltonLJ3rdYawnBPSilent pain sufferersMayo Clin Proced200681167171

- NellesenDYeeKChawlaALewisBECarsonRTA systematic review of the economic and humanistic burden of illness in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic constipationJ Manage Care Pharm201319674755

- JohansonJFKralsteinJChronic constipation: a survey of the patient perspectiveAliment Pharmacol Therapeut200725599608

- CarreteroSGarcésJRódenasFSanjoséVThe informal caregiver’s burden of dependent people: theory and empirical reviewArch Gerontol Geriatr200949747918597866

- KuzuyaMEnokiHHasegawaJImpact of caregiver burden on adverse health outcomes in community-dwelling dependent older care recipientsAm J Geriatr Psychiatry20111938239120808120

- GreenwoodNMackenzieAHabibiRAtkinsCJonesRGeneral practitioners and carers: a questionnaire survey of attitudes, awareness of issues, barriers and enablers to provision of servicesBMC Fam Pract20101110021172001

- KönigHHHeiderDLehnertTESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 investigatorsHealth status of the advanced elderly in six European countries: results from a representative survey using EQ-5D and SF-12Health Qual Life Out20108143

- NützelADahlhausAFuchsASelf-rated health in multimorbid older general practice patients: a cross-sectional study in GermanyBMC Fam Pract201415124387712

- PerrucioAKatzJLosinaEHealth burden in chronic disease: multimorbidity is associated with self-rated health more than medical comorbidity aloneJ Clin Epidemiol20126510010621835591

- GalenkampHBraamAWHuismanMDeegDJSomatic multimorbidity and self-rated health in the older populationJ Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci201166B38038621441387

- CasselEDiagnosing suffering: a perspectiveAnn Intern Med199913153153410507963

- FriedTRMcGrawSAgostiniJVTinettiMEViews of older persons with multiple morbidities on competing outcomes and clinical decision-makingJ Am Geriatr Soc2008561839184418771453