?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objective

To determine the adherence status to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) among epilepsy patients; to observe the association between adherence status and age, sex, active ingredient prescribed, treatment period, and number of comorbidities; and to determine the effect of nonadherence on direct medicine treatment cost of AEDs.

Methods

A retrospective study analyzing medicine claims data obtained from a South African pharmaceutical benefit management company was performed. Patients of all ages (N=19,168), who received more than one prescription for an AED, were observed from 2008 to 2013. The modified medicine possession ratio (MPRm) was used as proxy to determine the adherence status to AED treatment. The MPRm was considered acceptable (adherent) if the calculated value was ≥80%, but ≤110%, whereas an MPRm of <80% (unacceptably low) or >110% (unacceptably high) was considered nonadherent. Direct medicine treatment cost was calculated by summing the medical scheme contribution and patient co-payment associated with each AED prescription.

Results

Only 55% of AEDs prescribed to 19,168 patients during the study period had an acceptable MPRm. MPRm categories depended on the treatment period (P>0.0001; Cramer’s V=0.208) but were independent of sex (P<0.182; Cramer’s V=0.009). Age group (P<0.0001; Cramer’s V=0.067), active ingredient (P<0.0001; Cramer’s V=0.071), and number of comor-bidities (P<0.0001; Cramer’s V=0.050) were statistically but not practically significantly associated with MPRm categories. AEDs with an unacceptably high MPRm contributed to 3.74% (US$736,376.23) of the total direct cost of all AEDs included in the study, whereas those with an unacceptably low MPRm amounted to US$3,227,894.85 (16.38%).

Conclusion

Nonadherence to antiepileptic treatment is a major problem, encompassing ~20% of cost in our study. Adherence, however, is likely to improve with the treatment period. Further research is needed to determine the factors influencing epileptic patients’ prescription refill adherence.

Introduction

Approximately 50 million people globally suffer from epilepsy, of whom ~85% live in developing countries.Citation1 According to the World Health Organization, the annual incidence in developed countries is ~50 per 100,000 of the general population, whereas in developing countries the incidence is nearly 100 per 100,000.Citation1 The most recent prevalence studies conducted in South Africa in 2000 and 2014 reported a lifetime prevalence of 7.3/1,000 in children of a rural district and a crude adjusted prevalence of 7.0/1,000 in children of a rural northeast district.Citation2,Citation3

Epilepsy has a major impact on the general health of patients and influences the quality of life, performance at work and school, and everyday social life.Citation4 Furthermore, epilepsy carries an increased risk for seizure-related injuries and mortality compared with the general population.Citation5–Citation8

Although antiepileptic drug (AED) therapy does not offer a permanent cure to epilepsy, successful therapy can eliminate or reduce symptoms. Adherence to AEDs (defined as the extent to which patients are able to follow the recommendations for prescribed treatments) is subsequently a key to treatment success.

Nonadherence with medication is a complex problem that has many determinants. According to the World Health Organization,Citation9 the factors affecting adherence can be grouped into the following five dimensions: socioeconomic-related factors, health care team/health system-related factors, condition-related factors, treatment-related factors, and patient-related factors. Patients may be nonadherent at any time during their treatment,Citation10 eg, they may use more or less than the prescribed treatment or discontinue treatment prematurely.Citation11 Insufficient monthly supply (undersupply) of medication leads to inadequate treatment with subsequent uncontrolled seizures and poor quality of life,Citation12–Citation18 morbidity, and mortality,Citation19,Citation20 whereas the oversupply of medication may lead to potential toxicitiesCitation21 and increased health care costsCitation22–Citation27 or wasted resources.Citation28 Both undersupply and oversupply of medicine are considered to be forms of nonadherence.Citation23,Citation29 The prevalence of nonadherence to AEDs in patients with epilepsy generally tend to be high,Citation9 ranging from 20% to 80%Citation13,Citation15,Citation30–Citation34 depending on the populations studied, definition used for nonadherence, and research methods.Citation35 The assessment of adherence should be a routine action in the management of epilepsy – not only to improve patients’ health, but also as a cost-saving initiative.

There is paucity of information on the prevalence and economic consequences of nonadherence in South Africa. The aim of this study was 1) to determine the adherence status to AEDs among epilepsy patients in the private health sector of South Africa and observe whether there is an association between the adherence status (modified medicine possession ratio [MPRm] categories) and age, sex, active ingredient prescribed, treatment period, and number of comorbidities, and 2) to determine the effect of nonadherence on the direct medicine treatment cost of AEDs.

Methods

Patients and study design

We conducted a retrospective, longitudinal study analyzing medicine claims data obtained from a South African pharmaceutical benefit management company. Continuously enrolled patients of all ages, who were prescribed one or more AEDs over a 6-year period from January 1, 2008 to December 31, 2013, were eligible for the analysis.

We extracted data regarding patient demographics (sex and date of birth) and pertinent prescription information (such as drug trade name, days supplied, dispensing date, quantity of medicine prescribed, and the Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases [ICD-10] code per claim). The quality of the data was ascertained by means of several automated validation processes applied by the pharmaceutical benefit management company, such as data integrity validation and eligibility management.

This study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of the North-West University (NWU-00179-14-A1). Permission for the use of the data was granted by the board of directors of the pharmaceutical benefit management company. The data were analyzed anonymously. Privacy and confidentiality of the data were maintained at all times, and therefore no patient or medical scheme could be traced.

Inclusion criteria

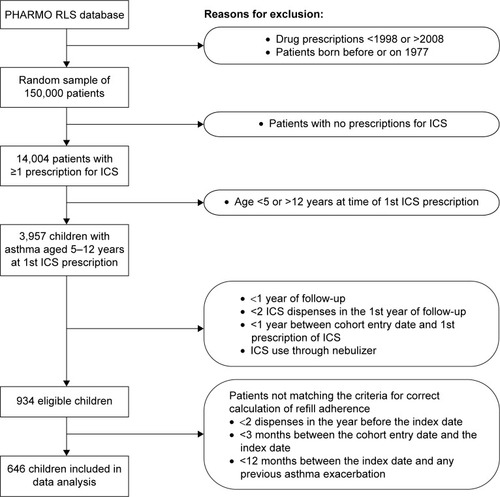

Patients were included in the study if they 1) had a recorded diagnosis of epilepsy (ICD-10 code G40) during the study period in conjunction with a paid claim reimbursed through the prescribed minimum benefit (PMB) as part of the chronic disease list (CDL) for antiepileptic medicine; and 2) filled a prescription for single or multiple AEDs more than once during the study period ().

Study population

A total of 45,250,902 prescriptions were analyzed. The study population was narrowed down to 20,210 patients receiving antiepileptic medication (defined as drugs from the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification group: N03AA, N03AB, N03AE, N03AD, N03AF, N03AG, and N03AX) during the study period, by applying the inclusion criteria. Of these patients, 19,168 patients received more than one prescription for an AED over the study period ().

Adherence measure

The MPRm measure was used as a proxy to determine adherence. The MPRm is an adherence percentage value that is an internationally accepted and well-documented method to calculate drug adherence in pharmacoepidemiological studies and chronic diseases.Citation36–Citation39 The MPRm measure is calculated from the medicine claims data by using the following formula:Citation40

Adherence measures based on the MPRm provide an indication of the possession of the medicine by the patient; however, the consumption of the medication by the patient can only be assumed to follow from the possession.Citation41 On the basis of pharmacy refill data, patients with medications available 80% of the time have generally been categorized as adherent in the literature.Citation25,Citation42 The MPRm was thus considered acceptable if the calculated value is ≥80%, but ≤110%. An MPRm of less than 80% indicates undersupply of medication or the presence of refill gaps, so that possession is considered unacceptably low and nonadherent, whereas an MPRm greater than 110% (oversupply) was deemed unacceptably high and thus also nonadherent. Oversupply represents possible waste and exhaustion of resources, whereas undersupply represents opportunity cost.Citation28

Measurement of direct medicine treatment cost

Direct medicine treatment cost of AEDs was calculated by summing the medical scheme contribution and patient co-payment associated with each AED. The direct cost of oversupply was calculated by multiplying the average direct medicine cost per day with the total number of days supplied, subtracting the number of days the patient was supposed to receive the medication. Opportunity cost (cost of undersupply) was determined by calculating the average direct medicine cost per day with the number of days the patient was supposed to have received the medication, subtracting the total number of days supplied. Medicine cost was calculated in South African rand and converted to US dollars (average conversion rate 2008–2013: 0.1238).Citation43

Study variables

Variables (age, sex, treatment period, active ingredients, and other comorbidities) were expressed using frequencies, percentages, mean, standard deviation (SD), and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Patient age was calculated at the date of the first dispensing on the database in relation to his/her date of birth, and was used to categorize patients into five age groups: 0≤12 years, >12 to ≤18 years, >18 to ≤40 years, >40 to ≤65 years, and >65 years and older.

Treatment duration was calculated as the days from the first prescription for AEDs up to the date of the last prescription, and divided into three groups: ≤30 days; >30 to ≤120 days, and >120 days. The treatment period can be described as the number of days the patient was supposed to receive medication.

The comorbid conditions were considered to be those chronic conditions registered on the South African PMB CDL. By definition, the PMB CDL, as a feature of the Medical Schemes Act 131 of 1998, is a regulated compilation of 25 conditions requiring treatment for over 12 months that are most common to the country, are considered to be life-threatening, and conditions where cost-effective treatment will sustain and improve the quality of the member’s life. Medical aid schemes are obliged to cover the costs related to the diagnosis, treatment, and ongoing care of these conditions, to the extent that this is provided for by way of a therapeutic algorithm for the specified condition.Citation44,Citation45 The CDL conditions were identified based on the presence of the following ICD-10 codes on claims reimbursed from patients’ PMB benefits: Addison’s disease (ICD-10 code E27.1), asthma (J45, J45.8), bronchiectasis (J47, Q33.4), cardiac failure (I50, I50.0, I50.1), cardiomyopathy (I42, I42.0, I25.5), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (J43, J44), chronic renal disease (N03, N11, N18), coronary artery disease (I20, I20.0, I25), Crohn’s disease (K50, K50.8), diabetes insipidus (E23.2), diabetes mellitus type 1 and 2 (E11.0–E11.9), dysrhythmias (I47, I47.2, I48), epilepsy (G40, G40.8), glaucoma (H40, Q15.0), hemophilia (D66, D67), dyslipidemia (E78.0–E78.5), hypertension (I10.0, I11.0, I12.0, I13.0, I15.0), hypothyroidism (E02, E03, E03.8), multiple sclerosis (G35), Parkinson’s disease (G20, G21), rheumatoid arthritis (M05, M06, M08.0), schizophrenia (F20), systemic lupus erythematous (M32, L93, L93.2), and ulcerative colitis (K51, K51.9).

Statistical analysis

Data management and analysis were performed by the SAS program version 9.3® (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A probability of P<0.0001 was considered statistically significant. The practical significance of the results was computed when the P-value was statistically significant.

The chi-square test was used to compare the statistically significant associations between two categorical variables. Cramer’s V value was used to test the strength for any association or practical significance from the chi-square analysis. It could be interpreted as follows: effect size of 0.1 is small, effect size of 0.3 is medium, and an effect size of 0.5 is large.Citation46

Results

displays the basic characteristics of the study population. The mean age of the 19,168 patients in the study population was 45.61 (SD =21.96) years, with more than half of these patients being women ().

Table 1 Patient demographics

Of the total 47,407 AEDs claimed during the study period (), only 55.14% were associated with an acceptable MPRm. A further 30.58% of AEDs had an unacceptably low MPRm, whereas 14.27% had an unacceptably high MPRm. A chi-square test of independence was furthermore performed to examine the association between MPRm categories and age, sex, active ingredient prescribed, treatment period, number of comorbidities, and direct AED cost. Based on this analysis, the relationship between MPRm categories and sex was independent (P<0.018; Cramer’s V=0.009), whereas the relationship between MPRm categories and age was statistically but not practically significant (P<0.0001; Cramer’s V=0.067). Analysis within the acceptable MPRm category, however, showed that the percentage of AEDs increased by age from 46.41% in patients aged 0 to ≤12 years to 61.50% (N=26,142) in those aged >65 years.

Table 2 Modified medicine possession ratio (MPRm) for antiepileptic drugs

The top ten most dispensed active ingredients (N=43,133) accounted for 90.98% of all AEDs (). These included valproate (22.55%), lamotrigine (21.96%), carbamazepine (15.62%), topiramate (8.21%), phenytoin (8.05%), clonazepam (5.33%), levetiracetam (3.79%), gabapentin (2.27%), valproic acid (2.25%), and oxcarbazepine (0.96%). A statistically significant association was observed between the type of active ingredient and MPRm categories; however, this association was not practically significant (Cramer’s V=0.071) (). Analysis within each active ingredient group showed that the AED with the highest acceptable MPRm was oxcarbazepine (64.5%), followed by valproic acid (63.7%) and phenytoin (58.7%). The AEDs with the highest unacceptably low MPRm included gabapentin (38.07%, N=1,077) and clonazepam (32.87%, N=2,528), whereas levetiracetam (19.55%, N=1,795) and topirimate (16.32%, N=3,892) had the highest unacceptably high MPRm ().

Treatment period was statistically and practically significantly associated with MPRm categories (P>0.0001; Cramer’s V=0.208). AEDs prescribed for longer than 120 days were more likely to be associated with an acceptable MPRm than were AEDs prescribed for less than 30 days ().

In the majority of cases where AEDs (58.41%, N=47,407) were prescribed, the patients did not present with other comorbidities. Furthermore, the number of comorbid conditions were statistically but not practically significantly associated with MPRm categories (P≤0.0001; Cramer’s V=0.05) ().

shows the direct AED cost associated with the different MPRm categories. Medical aid schemes contributed 75.97% (US$14,972,164.61) toward the cost over the study period. AEDs with an unacceptably high MPRm amounted to US$736,376.23 (3.74%) of the total cost of AEDs over the 6-year period. One-third of AEDs had an unacceptably low MPRm, representing an opportunity cost of US$3,227,894.85 (16.38%) ().

Table 3 Direct medicine cost associated with MPRm categories

Discussion

Nonadherence in patients taking AEDs is a major concern, not only in developed countries but also in middle-income countries such as South Africa. Although the 55.14% adherence rate described in this study was in range with findings from studies conducted on medical care claims databasesCitation13,Citation15,Citation30–Citation34 and studies conducted in the public health sector of South Africa (eg, 54.6% and 42.9%, respectively),Citation47,Citation48 it is still relatively poor compared to the advocated 80%.Citation25,Citation42 These findings underscore the importance of assessing adherence to AEDs in the South African health sector.

According to Garnett,Citation49 there are generally three types of factors that may influence medication adherence to AEDs in particular: 1) patient-related factors such as forgetfulness and stigmatization; 2) medication-related factors such as cost, side effects, number of medications prescribed, and dosing frequency; and 3) disease-related factors including seizure type and severity and duration of illness. Other factors that may also influence adherence to AEDs include not having enough medication on hand,Citation18 poor understanding and low health literary,Citation50,Citation51 impairment (eg, poor eye sight),Citation50 lack of counseling and/or communication skills, time and appropriate knowledge among health care workers,Citation48 changes to a new regime or a new formulation,Citation52 and socioeconomic status.Citation53 In this study, we identified a longer treatment period as potential predictor of adherence to AEDs, similar to several other studies.Citation31,Citation34,Citation54 According to Sweileh et al,Citation31 this may be due to the patients’ realization of the benefits of adherence through time, or because they are willing to tolerate side effects of AEDs and adhere to their medication regimens as long as they are satisfied with the effectiveness of these regimens.

In our study, the relation between adherence status and age was statistically but not practically significant. The available literature is conflicting in its findings with regard to the association between age and adherence to AEDs, with some studies showing that younger patients were less adherent with AEDs,Citation55,Citation56 whereas others suggested otherwise,Citation31,Citation32 or no association.Citation57,Citation58 Explanations raised for these findings included that older patients may realize the importance and benefits of adherence and therefore be more adherent.Citation31,Citation32 On the other hand, studies that have shown that adherence decreases with increasing ageCitation59,Citation60 indicated cost, medical insurance, or forgetfulness as main reasons for nonadherence. According to Cooper et al,Citation61 however, age by itself is not the determining factor in medication nonadherence. Many factors may combine to render a person less able to adhere to their medication regimens; these include the specific illness, the treatment time frame, medication regimen, and the cognitive/affective status of the patient.

AED adherence was independent of sex in the present study. Women are generally less likely than men to be adherent in their use of chronic medicationsCitation60,Citation62 and to receive medication treatment and monitoring recommended by clinical guidelines.Citation62 According to Harden et al,Citation63 this may be ascribed to the stigma associated with epilepsy; however, this usually depends on the patient’s situation and attitude.Citation64

Similar to findings by Baker et alCitation65 and Zeber et al,Citation66 the top three active ingredients that represented the highest adherence rate were oxcarbazepine, valproic acid, and phenytoin. These AEDs are given as first-line treatment, have available generics and the extended release formsCitation67 that make once-a-day dosing possible,Citation68,Citation69 which may be the reason for the high adherence rates observed in our study. Gabapentin and clonazepam, on the other hand, were more likely to be undersupplied, and topirimate and levetiracetam oversupplied, supporting results by Zeber et al showing that gapapentin use may significantly less likely to be adherent, whereas levetiracetam was positively associated with adherence. Drugs that cause cognitive difficulty or weight gain normally affect adherence, particularly if the patient has not been on treatment for long periods.Citation66 Weight gain and cognitive difficulty are commonly associated with the mood stabilizers such as valproic acid (sodium valproate) and to a lesser extent with carbamazepine, and some of the newer anticonvulsants such as vigabatrin and gabapentin.Citation70

Only ~40% of patients from our study population receiving AEDs presented with other comorbidities. There was also no practically significant association between the number of comorbidities and adherence as measured using the MPRm. Current literature studies report conflicting results, with some of these studies reporting a lower adherence with multiple comorbid conditions,Citation60,Citation71,Citation72 whereas others indicated a better adherence rate as the number of coexisting conditions increased.Citation30 Reasons cited for a lower adherence rate in patients with coexisting conditions include that they may require complex treatment regimens. As treatment complexity increases, patients’ understanding of the treatment regimen may decrease, leading to failure to take medications as prescribed.Citation73 Treatment complexity may also interfere with symptom control.Citation56

Nonadherence to medication does not only have a negative impact on clinical outcomes, but also on the economic consequences. Undersupply of medication contributed to 16.38% of the total direct costs associated with AEDs in our study. These patients who were undersupplied in terms of medicine (30.58%) possibly did not receive adequate treatment and did not reach optimal therapeutic effect. On the other hand, oversupply of medication contributed to 3.74% of the total direct costs associated with AEDs on the database over the study period. Nonadherence to antiepileptic treatment therefore encompassed ~20% of cost in our study. South Africa spent ~8.9% of its Gross Domestic Product on health sector financing in 2013, way more than the 5% recommended by the World Health Organization.Citation74 One of the primary cost drivers of medical expenditure in the private health sector during this time has been medicines, accounting for 15.8% of the total spent by medical aid schemes during the 2012/2013 financial year. Other main contributors to medical scheme costs were hospitals and specialists, accounting for 36.4% and 23.3% of expenditure, respectively.Citation75 This underscores the importance of assessing prescription refill adherence to AEDs in the South African health sector, enabling prompt response to potential health concerns and avoiding unnecessary costs.

Finally, our study adds to the limited literature on nonadherence to AEDs and associated cost implications in epilepsy patients in the private health sector of South Africa. The MPRm, albeit based on the assumption that patients take all medications for which they have prescriptions filled, allows for evaluation of adherence levels using pharmaceutical claims data. Limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results include that patients may also have acquired prescription medications from sources other than the pharmacies included in the database, or paid out-of-pocket for medicines, in which case the prevalence of nonadherence may be overestimated. The number of comorbidities investigated in the epileptic patients was a special group of diagnoses covered by the CDL in the PMB. These conditions were chosen due to the fact that they are covered by medical aid schemes (doctor’s consultations, tests related to condition and medication cover), even if a member’s benefits for the year have run out. The prevalence of comorbidities and their influence on adherence could therefore also be underestimated. Because we analyzed pharmaceutical claims data, we could not assess the pertinent reasons for patient’s prescription refill adherence in our study.

Conclusion

We showed that the adherence with AEDs for epileptic patients in the South African private health sector as determined on the claims database was relatively poor. We furthermore established that the poor adherence with AED treatment contributed significantly to an added cost in the treatment of epilepsy in a middle-income country such as South Africa.

The responsibility for adherence must be shared by health professionals, the health care system, the community, and patients.Citation9 Awareness should therefore be created among health professionals with regard to current prescribing patterns of AEDs, the level of nonadherence, and the subsequent cost implications thereof. Further studies to determine the factors influencing epileptic patients’ prescription refill adherence would be a logical next step in this field of research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Anne-Marie Bekker for administrative support regarding the database.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WHO (World Health Organization)EpilepsyGenevaWorld Health Organization2015 Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs999/en/index.htmlAccessed August 19, 2015

- ChristainsonALZwaneMEMangaPRosenEVenterAKrombergJGEpilepsy in rural South African children: prevalence, associated disability and managementS Afr Med J200090326226610853404

- WagnerRGNgugiAKTwineRPrevalence and risk factors for active convulsive epilepsy in rural northeast South AfricaEpilepsy Res2014108478279124582322

- BirbeckGLHaysRDCuiXVickreyBGSeizure reduction and quality of life improvements in people with epilepsyEpilepsia200243553553812027916

- TiamkaoSKaewkiowNPranbulSfor Integrated Epilepsy Research GroupValidation of a seizure-related injury modelJ Neurol Sci20143361–211311524209899

- NeiMBaglaRSeizure-related injury and deathCurr Neurol Neurosci Rep20077433534117618541

- BellonMWalkerCPetersonCSeizure-related injuries and hospitalizations: self-report data from the 2010 Australian Epilepsy Longitudinal SurveyEpilepsy Behav201326171023201608

- CamfieldCCamfieldPInjuries from seizures are a serious, persistent problem in childhood onset epilepsy: a population-based studySeizure201527808325891933

- SabatéEAdherence to Long-term Therapies: Evidence for ActionGenevaWorld Health Organization2003

- VrijensBDe GeestSHughesDAfor ABC Project TeamA new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medicationsBr J Clin Pharmacol201273569170522486599

- HugtenburgJGTimmersLEldersPJVervloetMvan DijkLDefinitions, variants, and causes of nonadherence with medication: a challenge for tailored interventionsPatient Prefer Adherence2013767568223874088

- HednaKHäggSAndersson SundellKPetzoldMHakkarainenKMRefill adherence and self-reported adverse drug reactions and sub-therapeutic effects: a population-based studyPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf201322121317132524127242

- HovingaCAAsatoMRManjunathRAssociation of non-adherence to antiepileptic drugs and seizures, quality of life, and productivity: survey of patients with epilepsy and physiciansEpilepsy Behav200813231632218472303

- JonesRMButlerJAThomasVAPevelerRCPrevettMAdherence to treatment in patients with epilepsy: associations with seizure control and illness beliefsSeizure200615750450816861012

- CramerJAGlassmanMGRienziVThe relationship between poor medication compliance and seizuresEpilepsy Behav20023433834212609331

- SamsonsenCReimersABråthenGHeldeGBrodtkorbENonadherence to treatment causing acute hospitalizations in people with epilepsy: an observational, prospective studyEpilepsia20145511e125e12825252007

- LadnerTRMorganCDPomerantzDJDoes adherence to epilepsy quality measures correlate with reduced epilepsy-related adverse hospitalization: a retrospective experienceEpilepsia2015565e63e6725809720

- ManjunathRDavisKLCandrilliSDEttingerABAssociation of antiepileptic drug nonadherence with risk of seizures in adults with epilepsyEpilepsy Behav200914237237819126436

- SanderJWBellGSReducing mortality: an important aim of epilepsy managementJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr200475334935114966142

- FaughtEDuhMSWeinerJRGuérinACunningtonMCNonadherence to antiepileptic drugs and increased mortality: findings from the RANSOM studyNeurology200871201572157818565827

- FredianiFCannatàAPMagnoniAPeccarisiCBussoneGThe patient with medication overuse: clinical management problemsNeurol Sci200324Suppl 2s108s11112811605

- StroupeKTMurrayMDStumpTECallahanCMAssociation between medication supplies and healthcare costs in older adults from an urban healthcare systemJ Am Geriatr Soc200048776076810894314

- KingsmanKMelanderACarlstenAEkedahlANilssonJLRefill non-adherence to repeat prescriptions leads to treatment gaps or to high extra costsPharm World Sci2007291192417268941

- DavisKLCandrilliSDEdinHMPrevalence and cost of nonadherence with antiepileptic drugs in an adult managed care populationEpilepsia200849344645418031549

- EttingerABManjunathRCandrilliSDDavisKLPrevalence and cost of non-adherence to anti-epileptic drugs in elderly patients with epilepsyEpilepsy Behav200914232432919028602

- IugaAOMcGuireMJAdherence and health care costsRisk Manag Healthc Policy20147354424591853

- FaughtREWeinerJRGuérinACunningtonMCDuhMSImpact of nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs on health care utilization and costs: findings from the RANSOM studyEpilepsia200950350150919183224

- YHEC/School of PharmacyUniversity of London2010Evaluation of the Scale, Causes and Costs of Waste Medicines Available from: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1350234/1/Evaluation_of_NHS_Medicines_Waste_web_publication_version.pdfAccessed January 10, 2016

- ChenCCBlankRHChengSHMedication supply, healthcare outcomes and healthcare expenses: longitudinal analysis of patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertensionHealth policy2014117337438124795290

- BriesacherBAAndradeSEFouayziHChanKAComparison of drug adherence rates among patients with seven different medical conditionsPharmacotherapy200828443744318363527

- SweilehWMIhbeshehMSJararISSelf-reported medication adherence and treatment satisfaction in patients with epilepsyEpilepsy Behav201121330130521576040

- LusićITitlićMEterovićDEpileptic patient compliance with prescribed medical treatment [abstract]Acta Med Croatica2005591131815813351

- AsawavichienjindaTSitthi-AmornCTanyanontWCompliance with treatment of adult epileptics in a rural district of ThailandJ Med Assoc Thai2003861465112678138

- HodgesJCTreadwellJMalphrusADTranXGGiardinoAPIdentification and prevention of antiepileptic drug noncompliance: the collaborative use of state-supplied pharmaceutical dataISRN Pediatr2014201473468924693446

- MantriPMedication adherence in adults with epilepsyPract Nurs2015264179184

- AndradeSEKahlerKHFrechFChanKAMethods for evaluation of medication adherence and persistence using automated databasesPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf200615856557416514590

- MarcumZAGurwitzJHColόn-EmericCHanlonJTPills and ills: methodologic issues in pharmacologic researchJ Am Geriatr Soc201563482983025900504

- ParkHRascatiKLLawsonKABarnerJCRichardsKMMaloneDCAdherence and persistence to prescribed medication therapy among Medicare part D beneficiaries on dialysis: comparisons of benefit type and benefit phasesJ Manag Care Spec Pharm201420886287625062080

- ThierSLYu-IsenbergKSLeasBEIn chronic disease, nationwide data show poor adherence by patients to medication and by physicians to guidelinesManag Care2008172485718361259

- KarveSClevesMAHelmMHudsonTJWestDSMartinBCProspective validation of eight different adherence measures for use with administrative claims data among patients with schizophreniaValue Health200912698999519402852

- SikkaRXiaFAubertREEstimating medication persistency using administrative claims dataAm J Manag Care200511744945716044982

- OsterbergLBlaschkeTAdherence to medicationN Engl J Med2005353548749716079372

- OANDA Corporationc1996–c2015Currency converter Available from: http://www.oanda.com/currency/converter/Accessed August 27, 2015

- Council for Medical Schemes, South Africa2010Prescribed minimum benefits (PMB’s) aim to provide you with continuous care Available from: http://www.medicalschemes.com/ReadNews.aspx?2Accessed February 01, 2015

- Council for Medical Schemes, South Africa1998Medical Schemes Act, 131 of 1998 Available from: https://www.medicalschemes.com/Content.aspx?130Accessed February 01, 2015

- EllisSMSteynHSPractical significance (effect sizes) versus or in combination with statistical significance (p-values)Manag Dynam20031245153

- EgenasiaCSteinbergaWJRaubenheimerJEBeliefs about medication, medication adherence and seizure control among adult epilepsy patients in Kimberley, South AfricaSA Fam Pract2015575326332

- KrauseSRVan RooyenFCVan VuurenMVJJenkinsLNon-compliance with treatment by epileptic patients at George Provincial HospitalSA Fam Pract200749914a14d

- GarnettWRAntiepileptic drug treatment: outcomes and adherencePharmacotherapy2000208 Pt 2191S199S10937819

- MbubaCKNguguAKFeganGRisk factors associated with the epilepsy treatment gap in Kilifi, Kenya: a cross-sectional studyLancet Neurol201111868869622770914

- KeikelameMJSwartzLLost opportunities to improve health literacy: observations in a chronic illness clinic providing care for patients with epilepsy in Cape Town South AfricaEpilepsy Behav2013261364123207515

- BuckDJacobyABakerGAChadwickDWFactors influencing compliance with antiepileptic drug regimesSeizure19976287939153719

- PaschalAMRushSESadlerTFactors associated with medication adherence in patients with epilepsy and recommendations for improvementEpilepsy Behav20143134635024257314

- ShettyJKirkpatrickMGreeneSAdherence to anti-epileptic medication in children with epilepsy from a Scottish population cohortArch Dis Child201297Suppl 1A135

- TanXCMakmor-BakryMLauCLTajarudinFWRaymondAAFactors affecting adherence to antiepileptic drugs therapy in MalaysiaNeurol Asia2015203235241

- FerrariCMMde SousaRMCastroLHMFactors associated with treatment non-adherence in patients with epilepsy in BrazilSeizure201322538438923478508

- GurumurthyRChandaKSarmaGAn evaluation of factors affecting adherence to anti-epileptic drugs in patients with epilepsy: a cross-sectional studySingapore Med J Epub2016125

- GabrWMShamsMEAdherence to medication among outpatient adolescents with epilepsySaudi Pharm J2015231334025685041

- BautistaREDRundle-GonzalezVEffects of antiepileptic drug characteristics on medication adherenceEpilepsy Behav201223443744122405862

- RolnickSJPawloskiPAHedblomBDAscheSEBruzekRJPatient characteristics associated with medication adherenceClin Med Res2013112546523580788

- CooperJKLoveDWRaffoulPRIntentional prescription nonadherence (noncompliance) by the elderlyJ Am Geriatr Soc19823053293337077010

- ManteuffelMWilliamsSChenWVerbruggeRRPittmanDGSteinkellnerAInfluence of patient sex and gender on medication use, adherence, and prescribing alignment with guidelinesJ Womens Health (Larchmt)201423211211924206025

- HardenCThomasSVTomsonTEpilepsy in WomenOxfordJohn Wiley & Sons2013

- AhmedRAslaniPImpact of gender on adherence to therapyJ Malta College Pharm Pract2014202123

- BakerGAJacobyABuckDStalgisCMonnetDQuality of life of people with epilepsy: a European studyEpilepsia19973833533629070599

- ZeberJECopelandLAPughMJVariation in antiepileptic drug adherence among older patients with new-onset epilepsyAnn Pharmacother201044121896190421045168

- PeruccaETomsonTThe pharmacological treatment of epilepsy in adultsLancet Neurol201110544645621511198

- UthmanBMExtended-release antiepilepsy drugs: review of the effects of once-daily dosing on tolerability, effectiveness, adherence, quality of life, and patient preferenceUS Neurol20141013037

- Council for Medical Schemes, South AfricaMedical Schemes Act, 1998 (Act 131 of 1998). Regulations made in terms of the Medical Scheme Act, 1998 therapeutic algorithms for chronic conditions. (Notice 1402)Government Gazette20032553753111

- JallonPPicardFBodyweight gain and anticonvulsants: a comparative reviewDrug Saf2001241396997811735653

- MarcumZAGelladWFMedication adherence to multi-drug regimensClin Geriatr Med201228228730022500544

- SaadatZNikdoustFAerab-SheibaniHAdherence to antihypertensives in patients with comorbid conditionNephrourol Mon20157416

- McAuleyJWMcFaddenLSElliottJOShnekerBFAn evaluation of self-management behaviors and medication adherence in patients with epilepsyEpilepsy Behav200813463764118656553

- WHO (World Health Organization)2016Global Health Expenditure Database Available from: http://apps.who.int/nha/database/ViewData/Indicators/enAccessed January 28, 2016

- Council for Medical Schemes, South Africa2013 Available from: https://www.medicalschemes.com/files/Annual%20Reports/f0868c30e186Z.htmlAccessed January 28, 2016