Abstract

Parenting style experienced during childhood has profound effects on children’s futures. Scales developed in other countries have never been validated in the Tibetan context. The present study aimed to examine the construct validity and reliability of a Tibetan translation of the 23-item short form of the Egna Minnen Beträffande Uppfostran [One’s Memories of Upbringing] (s-EMBU) and to test the correlation between the parenting styles of fathers and mothers. A cross-sectional study was conducted in a sample of 847 students aged 12–21 years from Lhasa, Tibet, during September and October 2015 with a participation rate of 97.7%. The Tibetan translation of self-completed s-EMBU was administered. Confirmatory factor analysis was employed to test the scale’s validity on the first half of the sample and was then cross-validated with the second half of the sample. The final model consisted of six factors: three (rejection, emotional warmth, and overprotection) for each parent, equality constrained on factor loadings, factor correlations, and error variance between father and mother. Father–mother correlation coefficients ranged from 0.81 to 0.86, and the level of consistency ranged from 0.62 to 0.82. Thus, the slightly modified s-EMBU is suitable for use in the Tibetan culture where both the father and the mother have consistent parenting styles.

Background

Parenting style reflects parents’ attitudes toward their children which are then communicated to them, and the emotional climate in which these attitudes are expressed. Negative parenting style is one cause of early maladaptive schemas which can increase the risk of emotional problems such as anxiety and depression.Citation1–Citation5 Parenting style also has profound effects on cognitive outcomes reflected by academic achievement.Citation6–Citation9 Over the past 50 years, there have been a number of theories about the dimensions of parenting style. For example, Barber described a dimension of parental psychological control.Citation10

Parenting style is known to be culturally dependent. Loter found distinct parenting styles of mothers among three ethnic groups in Germany.Citation11 German mothers had a more permissive style, Vietnamese mothers displayed a more authoritarian style, whereas the prevailing parenting style for Turkish mothers was neglectful. In another study conducted in the US and the People’s Republic of China, Chinese parents tended to be more controlling than their Western counterparts.Citation12

In the People’s Republic of China, Tibetans are an ethnic minority group with a distinct culture, and most live in a relatively remote area with little social competition. Parents are relatively calm and communicative and rarely hit their children.Citation13 Although there have been a few studies looking at parenting styles of Tibetans, the scales were in Chinese or without validation.Citation14,Citation15 The use of these scales cannot overcome the cultural barriers.

The Egna Minnen Beträffande Uppfostran [One’s Memories of Upbringing] (EMBU) developed by Perris et alCitation16 in 1980 is among the most frequently used parenting style assessment scales.Citation17 Originally, EMBU had 81 items,Citation18 but the more commonly used short form (s-EMBU) has 23 items,Citation17,Citation19–Citation21 which has been proven to be practical in adults, adolescents, and psychiatric patients.Citation17,Citation21,Citation22

Agreement in parenting styles of the father and mother was shown to contribute to the social competence of children.Citation23–Citation27 Thus, correlation between the parenting styles of the father and mother was also tested in our study.

Our study objectives were to examine the construct validity and reliability of a Tibetan translation of the s-EMBU and to test the correlation between the parenting styles of father and mother.

Methods

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Lhasa, the capital city of Tibet Autonomous Region of China, during September and October 2015. In the 2010 National census, the population of Lhasa was ~559,000, of which 76% were Tibetans. To increase the variation of age, the subjects were recruited from one middle school, one high school, and one university, all of which were public schools.

Sample size and sampling

To yield a stable factor solution in factor analysis, a sample of at least 300 is generally required.Citation28 To validate and cross-validate the s-EMBU using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on two split halves of the data set, a sample size of at least 600 was required. Assuming a nonresponse rate of 25%, the sample size was increased to 800.

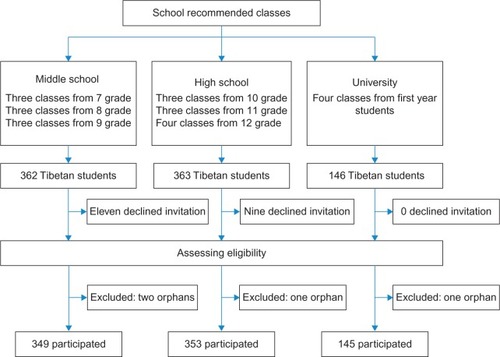

The detailed subject recruitment procedure is summarized in . Classes were chosen by the schools based on their readiness to participate. Inclusion criterion for the students was being Tibetan adolescents. Orphans and those with mental problems were excluded from the study. Of 871 students invited, 20 refused (response rate =97.7%) to participate in the study. Unwillingness in releasing certain personal information was the main reason for nonparticipation. After excluding four orphans, 847 Tibetan adolescents voluntarily participated in the study and no payment was given for participation.

Instruments

The original s-EMBU scaleCitation20,Citation21 has been used to assess three dimensions of parenting style, including rejection (seven items), emotional warmth (six items), and overprotection (ten items). Rejection is characterized by a critical and judgmental approach to parenting. Emotional warmth is shown through parenting attitudes of acceptance, support, and value; whereas, overprotection is characterized by being fearful for a child’s safety and having a high degree of control over them.

The scale includes father and mother forms with 23 items in each form. The items are scored on a four-point Likert scale (1: never; 2: yes, but seldom; 3: yes, often; 4: yes, always). The items of the original s-EMBU scale were randomly mixed and for the purposes of this study, the items were named as RF1_1-RF7_21, EF1_2-EF6_23, and OF1_3-OF10_22 for the father’s domain of rejection, emotional warmth, and overprotection, respectively. The mother’s domain of rejection, emotional warmth, and overprotection were renamed as RM1_1-RM7_21, EM1_2-EM6_23, and OM1_3-OM10 _22, respectively. The corresponding meaning of all items in the original questionnaire is described in .

Table 1 Names of the 23 items in the Tibetan version s-EMBU and corresponding items from original questionnaire

Procedures

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Hat Yai, Songkhla Province, Thailand (reference number: 57-187-18-5) before the research was conducted.

The English version of the s-EMBU was translated into the Tibetan language by one expert and back translated by another expert. After comparison, dissimilarities between the original English version and the back-translated English version were resolved by a third expert. All these three experts were Tibetans residing in Tibet Autonomous Region and had studied in an English speaking county for more than 5 years. The scale was further pretested on ten students from Tibet University whose opinions were incorporated into the final version.

For the students aged under 18 years, permission to be enrolled in the study was obtained from the student’s parents and school authorities. Otherwise, the permission was obtained by written informed consent from participants. The participants completed the s-EMBU (Tibetan version) and the questionnaire containing items on sociodemographic characteristics in their classrooms with necessary facilitation by a research assistant.

Analysis

The data set was randomly split into two groups of almost equal size (424:423). Since a three-factor structure of s-EMBU had already been established from a number of countries and cultures, CFA was employed to test the validity of the three-factor structure for each parent in the first data set and refined to obtain the most appropriate model. This model was then tested for fitness with the second half of the data set. In CFA, a maximum likelihood estimation method was used and the covariance matrix was analyzed to assess the fit of the model. LISREL version 8.8 was used to do the factor analysis and R version 3.2.2 was used for all other statistical analyses.

The following measures and cut points were employed to assess the fit of the CFA models: root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) <0.05 (good fit), <0.06 (acceptable);Citation29,Citation30 standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) <0.08 (good fit);Citation29,Citation30 comparative fit index (CFI) ≥0.90 (acceptable), ≥0.95 (good fit);Citation29,Citation30 and Tucker–Lewis index ≥0.90 (acceptable), ≥0.95 (good fit).Citation29,Citation30 In terms of factor loadings, the generally accepted cut point of 0.3, indicating medium loading, was used to include the items from the CFA.Citation29 A Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which is used to determine the internal consistencies of subscales, higher than 0.6 is considered acceptable.Citation31

A two-factor model with one factor for each parent, which indicates that all items in each of the parent’s forms represent only one domain, was fitted first. The main model was a six-factor model with three factors representing three parts for the father’s parenting style and another three factors for the mother’s parenting style. Previous studies reported findings on cross-loadings of item OF4_9/OM4_9 on emotional warmth and overprotection.Citation19,Citation21 These cross-loadings were also specified in the tested models. Since the items in the father and mother forms were identical and answered by the same participants, the covariance between residuals of the same item in father and mother forms was specified in all computations.

The initial main model was computed with different loadings for the father and mother. It was then simplified with constraints allowing parents to have the same loadings, same correlation coefficient between factors, and same variance in the error. To compare the nested models with and without equality constraints of factors loadings, factor correlations, and error variance in father and mother, the change in CFI (ΔCFI) <0.01 was used to identify the most efficient model.Citation29

Results

Demographic characteristics

The detailed characteristics of the students, their parents, and their families are presented in . The age of students ranged from 12.2 to 20.8 years (median =15.9, interquartile range =14.3–17.8), and females predominated the sample (53.0%). Regarding the education level of parents, around three-quarters of the mothers and two-thirds of the fathers had never been to school, or had attended primary school only.

Table 2 Sociodemographic characteristics of students and their parents

Construct validity of the s-EMBU

There were no significant differences between the two split data sets with respect to the children’s age and sex and the marital status and education level of parents.

summarizes the results of model selection. The null model with two factors (Model 1, one factor for each parent) was not valid by any criteria. Model 2 followed the methodology proposed by Arrindell et al,Citation21 that is, containing three factors for each parent, with a cross-loading of OF4_9/OM4_9 on emotional warmth and overprotection. This model fit the data well except that loadings for OF7_17/OM7_17 and OF4_9/OM4_9 on overprotection were low (<0.2). Model 3 was an improvement over Model 2, where the low loading items and path of OF4_9/OM4_9 on overprotection were removed. This improvement was evidenced by a slight increase in CFI and TLI. The good fit of Model 3 meant that the number of factors in the father and mother forms were the same. Model 4 was a further improvement over Model 3, where constraints on the factor loadings for the father and mother were equal, and the fit was acceptable. The fit of Model 4 was similar to Model 3 (ΔCFI =0.006). The equality of factor loadings in the father and mother forms denoted that the children perceived the parenting styles of their fathers and mothers in the same way. Model 5 was a further refinement of Model 4, where equal factor correlations were allowed between the mother and father with a minor reduction in CFI. In Model 6, for the aforementioned reason, the error variance of items was constrained to be equal and the model was still acceptable with ΔCFI =0.001. The equal error variance between father and mother indicates that the reliability of the two forms is similar. Although Model 6 included the fewest number of parameters, it showed only a small change in CFI, and thus was chosen as the final model. Fitting the model to the second half of the data set gave an acceptable fit – RMSEA (90% confidence interval) of 0.44 (0.041–0.048), SRMR of 0.074, Tucker–Lewis index of 0.940, and CFI of 0.942.

Table 3 Results from CFA of the s-EMBU on the first random subset of records

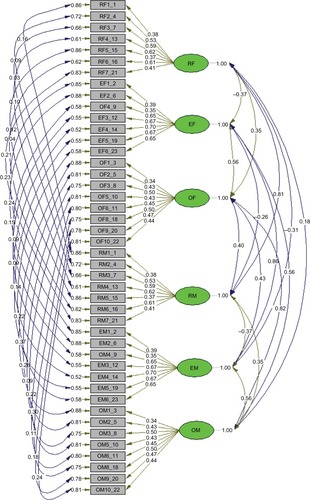

A path diagram of Model 6 with equality constraints on factor loadings, factor correlation, and error variance is shown in . All factor loadings were acceptable (being above 0.30).Citation29 A high factor loading of an item on a given construct indicates convergent validity of that item, implying it is a good measure for the construct. Four of seven items on rejection and five of seven items on emotional warmth had factor loadings greater than 0.5. However, factor loadings on all eight items of overprotection were between 0.34 and 0.50. Therefore, items on rejection and emotional warmth showed stronger evidence on convergent validity compared to those on overprotection.

Figure 2 Standardized solution from CFA of the s-EMBU for fathers and mothers (N=423).

Abbreviations: RF, father rejection; RM, mother rejection; EF, father emotional warmth; EM, mother emotional warmth; OF, father overprotection; OM, mother overprotection; s-EMBU, short form of the Egna Minnen Beträffande Uppfostran [One’s Memories of Upbringing]; CFA, confirmatory factor analysis.

The correlations among three types of parenting styles in father and mother ranged from −0.37 to 0.56 (), implying that each style was distinct. Rejection was negatively correlated with emotional warmth, while overprotection was positively correlated with both rejection and emotional warmth.

Reliability of the s-EMBU scale

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each subscale of parenting style are presented in . The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.62 to 0.82.

Table 4 Reliability of the s-EMBU subscales

Discussion

Our sample included Tibetan adolescents with a slightly higher proportion of females. A model with six factors, three for each parent, that is, equality constrained on factor loadings, factor correlations, and error variance between the father and mother forms, was found to be the most efficient one. The level of consistency was acceptable. Except for one item which needed to be removed and another item that needed to be transferred across to another domain, CFA suggested that the three factors underlying the scales are valid. The parenting styles of Tibetan fathers and mothers were highly correlated.

In this study, Tibetan children perceived the parenting styles of their fathers and mothers in the same way. The high correlation between the same factors in the father and mother models also indicated that their parenting styles were similar. The correlation in parenting style of the father and mother found in this population may reflect that marital conflict was not common. The consistent parenting style prevents confusion in the children, and thus is beneficial to them.Citation32

Since rearing behavior is culturally dependent on activities,Citation11 some items which were a good measure in the Western culture might not be suitable in a Tibetan context. The CFA in this study revealed that items OF7_17 and OM7_17 (I was allowed to go where I liked without my parents caring too much) had low loadings. This may indicate that this item is not suitable for the Tibetan children. However, the culturally specific reason for this is not clear. Furthermore, items OF4_9 and OM4_9 (My parents tried to spur me to become the best), originally designed to measure overprotection, was found to be a measure of emotional warmth in this study. This finding is consistent with those from studies in Australia, Venezuela, and Guatemala.Citation19,Citation21 Our finding in Tibetan children is understandable since parental control, especially on learning in school, may be perceived as an expression of care or concern and being acceptable by Asian children.Citation33 Thus, transfer of this item from the overprotection subscale to the emotional warmth subscale needs to be considered.

The reliability of all subscales in this study was acceptable. However, since the reliability of overprotection in the father form was rather low, further studies are needed to confirm this.

Strengths and limitations

The sample size of current study was big enough to yield a stable solution in CFA and confirm it. The homogenous culture of the study sample ensured the homogeneity of the study sample.

Since nonrandom sampling was employed, generalization of the results is limited. Convergent and discriminant validity was not tested thoroughly in relation to other scales.

Conclusion and implications

The revised Tibetan version of the s-EMBU could be used in the future for both research and clinical patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr Edward McNeil for helping edit the final manuscript. This study is part of the first author’s thesis to fulfill the requirements for a PhD degree in Epidemiology at Prince of Songkla University.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MousaviSLowWHashimAThe relationships between perceived parental rearing style and anxiety symptoms in Malaysian adolescents: the mediating role of early maladaptive schemasJ Depress Anxiety2016221671044

- KoernerNTallonKKusecAMaladaptive core beliefs and their relation to generalized anxiety disorderCogn Behav Ther201544644145526029983

- ShoreyRCElmquistJAndersonSStuartGLThe relationship between early maladaptive schemas, depression, and generalized anxiety among adults seeking residential treatment for substance use disordersJ Psychoactive Drugs201547323023826099037

- YoungBJWallaceDPImigMBorgerdingLBrown-JacobsenAMWhitesideSPParenting behaviors and childhood anxiety: a psychometric investigation of the EMBU-CJ Child Fam Stud201322811381146

- ChorpitaBFBarlowDHThe development of anxiety: the role of control in the early environmentPsychol Bull199812413219670819

- IshakZLowSFLauPLParenting style as a moderator for students’ academic achievementJ Sci Educ Technol2012214487493

- HueyELSaylerMFRinnANEffects of family functioning and parenting style on early entrants’ academic performance and program completionJ Educ Gift2013364418

- KarbachJGottschlingJSpenglerMHegewaldKSpinathFMParental involvement and general cognitive ability as predictors of domain-specific academic achievement in early adolescenceLearn Instr2013234351

- JabagchourianJJSorkhabiNQuachWStrageAParenting styles and practices of Latino parents and Latino fifth graders’ academic, cognitive, social, and behavioral outcomesHisp J Behav Sci2014362175194

- BarberBKParental psychological control: revisiting a neglected constructChild Dev1996676329633199071782

- LotterVParenting styles and perceived instrumentality of schooling in native, Turkish, and Vietnamese families in GermanyZ Erziehwiss2015184845869

- QinLPomerantzEMWangQAre gains in decision-making autonomy during early adolescence beneficial for emotional functioning? The case of the United States and ChinaChild Dev20098061705172119930347

- LiuMLongQInvestigation on parenting style status of college freshman of Tibet Autonomous RegionChina J Health Psychol2010181113621364

- YangPzFJHLJRelationship between parenting style and self-congruence in Tibetan middle school studentsChin Mental Health J2015294284289

- YangPZHLJThe relationship between parenting style and learning engagement of Tibet junior middle school studentsChina J Health Psychol201523710711074

- PerrisCJacobssonLLinndströmHKnorringLvPerrisHDevelopment of a new inventory for assessing memories of parental rearing behaviourActa Psychiatr Scand19806142652747446184

- LiZWangLZhangLExploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of a short-form of the EMBU among Chinese adolescentsPsychol Rep2012110126327522489392

- AlujaADel BarrioVGarciaLFComparison of several shortened versions of the EMBU: exploratory and confirmatory factor analysesScand J Psychol2006471233116433659

- ArrindellWAkkermanABagésNZaldivarFThe short-EMBU in Australia, Spain, and VenezuelaEur J Psychol Assess20052115666

- ArrindellWARichterJEisemannMThe short-EMBU in East-Germany and Sweden: a cross-national factorial validity extensionScand J Psychol200142215716011321639

- ArrindellWASanavioEAguilarGThe development of a short form of the EMBU: its appraisal with students in Greece, Guatemala, Hungary and ItalyPers Individ Dif1999274613628

- JonesCHarrisGLeungNParental rearing behaviours and eating disorders: the moderating role of core beliefsEat Behav20056435536416257809

- RyanRMMartinABrooks-GunnJIs one good parent good enough? Patterns of mother and father parenting and child cognitive outcomes at 24 and 36 monthsParent Sci Pract200662–3211228

- SimonsLGCongerRDLinking mother–father differences in parenting to a typology of family parenting styles and adolescent outcomesJ Fam Issues2007282212241

- LindseyEWMizeJInterparental agreement, parent–child responsiveness, and children’s peer competenceFam Relat2001504348354

- GambleWCRamakumarSDiazAMaternal and paternal similarities and differences in parenting: an examination of Mexican-American parents of young childrenEarly Child Res Q20072217288

- WinslerAMadiganALAquilinoSACorrespondence between maternal and paternal parenting styles in early childhoodEarly Child Res Q2005201112

- FieldAMilesJFieldZDiscovering Statistics Using RLondonSage2012769770

- BrownTAConfirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research2nd edNew YorkGuilford Publications201527284

- HuLtBentlerPMCutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternativesStruct Equ Modeling199961155

- AronACoupsEJAronENStatistics for Psychology6New York, NYPearson Education, Inc2012625627

- TavassolieTDuddingSMadiganAThorvardarsonEWinslerADifferences in perceived parenting style between mothers and fathers: implications for child outcomes and marital conflictJ Child Fam Stud201625620552068

- PomerantzEMWangQThe role of parental control in children’s development in Western and East Asian countriesCurr Dir Psychol2009185285289