Abstract

Research has studied family functioning in families of patients suffering from eating disorders (EDs), particularly investigating the associations between mothers’ and daughters’ psychopathological symptoms, but limited studies have examined whether there are specific maladaptive psychological profiles characterizing the family as a whole when it includes adolescents with anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and binge eating disorder (BED). Through the collaboration of a network of public and private consultants, we recruited n=181 adolescents diagnosed for EDs (n=61 with AN, n=60 with BN, and n=60 with BEDs) and their parents. Mothers, fathers, and youths were assessed through a self-report measure evaluating family functioning, and adolescents completed a self-report questionnaire assessing psycho-pathological symptoms. Results showed specific family functioning and psychopathological profiles based on adolescents’ diagnosis. Regression analyses also showed that family functioning characterized by rigidity predicted higher psychopathological symptoms. Our study underlines the importance of involving all members of the family in assessment and intervention programs when adolescent offspring suffer from EDs.

Introduction

Research has shown that eating disorders (EDs) and psychopathological symptoms among female adolescents are associated with problematic family functioning.Citation1–Citation4 EDs are common and serious mental disorders characterized by abnormal eating habits and severe subjective concern about body weight or shape, which typically occur at the beginning of puberty or in late adolescence.Citation5 In fact, early adolescence and puberty (11–14 years of life) represent transitional phases of life characterized by physical, psychological, and social modifications.Citation6–Citation8 In these stages, teenagers experience major and fast body changes, such that puberty could become a period of concern for body size and shape.Citation9 Moreover, the brain and the cognitive functions mature, there is an increased awareness of societal pressures for thinness and an increased concern about peer acceptance.Citation10,Citation11 For these reasons, although EDs can occur in individuals of all ages, adolescence represents a peak period for their onset.Citation12 Recent epidemiological research has shown that prevalence of EDs among adolescents is estimated to be 0.3% for anorexia nervosa (AN), 0.9% for bulimia nervosa (BN), and 1.6% for binge eating disorder (BED).Citation13,Citation14 Notwithstanding an increase of incidence of EDs in adolescent males over the last few decades,Citation15 EDs predominantly affect female adolescents, with a rate of 5.7% for girls versus 1.2% for boys;Citation16 moreover, adolescent girls usually show more severe symptoms of AN, BN, and BED if compared to same-age boys.Citation17

As suggested by many studies, based on a transactional theoretical framework, diagnosis of EDs in early adolescence is associated with both specific maladaptive family functioning and individual vulnerability.Citation1,Citation18 In particular, with regard to individual characteristics, although most studies have demonstrated a possible comorbidity between EDs and other psychiatric disorders (e.g., borderline personality disorders, avoidant personality disorders and depression [DEP]),Citation19,Citation20 other studies have shown significant associations also with various subclinical forms of psychological difficulties.Citation21–Citation23 Research has widely demonstrated that eating pathology in adolescent females is associated with emotional regulation difficulties, which are in turn correlated with obsessive–compulsive/perfectionistic and impulsive personality traits.Citation24–Citation26 Furthermore, empirical studies have evidenced that emotional disturbance can be a predisposing factor for internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescents affected by EDs.Citation27 In this regard, genetic and epigenetic research have shown that EDs are associated with both internalizing problems (e.g., anxiety [ANX], withdrawal, and depressive symptoms) and externalizing difficulties, including under-controlled, impulsive, and disinhibited cognitions and behaviors.Citation28–Citation30 With regard to family factors, recent studies have found associations between the difficulties of adolescents with EDs and family functioning, but no study, to our best knowledge, has investigated the impact of family psychopathological profiles on the adolescents’ psychopathological symptoms, differentiating for different types of EDs, during adolescence.

Indeed, increased demand for autonomy, which characterized the adolescence phase,Citation31 fosters a reorganization of family functioning,Citation32 and in particular, empirical studies have shown that various characteristics of family functioning (e.g., the presence of excessive dependence on other family members, low flexibility, poor communication, and avoidance of conflict) are associated with unhealthy weight-related behaviors, disordered eating behaviors,Citation33 and higher ED psychopathology,Citation34,Citation35 especially among daughters.Citation36,Citation37 It must be acknowledged that family pathology may be a result of the offspring disorder rather than its cause.Citation38 Within family system theory, Minuchin et alCitation39,Citation40 have defined these families as “psychosomatic families”,Citation41 highlighting that they are characterized by high levels of overprotectiveness, enmeshment, rigidity, and lack of conflict resolution, although efforts to empirically identify the psychosomatic family have generally been unsuccessful.Citation42 Furthermore, according to Olson’s Circumplex Model, these families may show unbalanced levels of cohesion (enmeshed families) and flexibility (rigid families).Citation43 The experience of unsatisfying family relationships has been suggested to be associated in offspring with many psychological dimensions, such as significant body dissatisfaction, the beauty ideal, maturity fears, interpersonal safety, perfectionism, and self-awareness.Citation34,Citation44 Moreover, Kivisto et alCitation45 found that adolescents who perceived higher family enmeshment also demonstrated greater emotional dysregulation in several domains, such as negative global appraisals of distress tolerance and a stronger increase in subjective negative mood. In a recent study, we investigated the differences in perceptions of family functioning of adolescents with EDs and their parents in a developmental psychopathology framework.Citation46 This study found that different perceptions of family functioning and peculiar psychopathological vulnerabilities were associated with the diagnosis of ED of adolescents.Citation47–Citation49

Based on the abovementioned premises and on our previous results, but building on a systemic-relational framework and assessing a new sample of adolescents and parents, in the present study, we aimed to assess the functioning of families with adolescents with EDs and to verify whether the characteristics of family functioning are associated with a specific form of ED in their offspring and with adolescents’ psychopathological profiles.

Methods

Participants

Among the total number of female adolescents (N=551; age range: 14–17 years) who visited a network of public and private consultants in central Italy, requesting clinical support for disordered eating, over a 1-year period (from January 2014 to February 2015), 329 adolescents were diagnosed by a group of trained psychologists for EDs according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria and recruited for this study.Citation50 From this sample, n=86 adolescents were diagnosed in comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders (n=42 with ANX disorders, n=31 with borderline personality disorder, and n=13 with DEP) and were excluded from the present study to remain focused on specific features of EDs. The sample fitting the inclusion criteria (n=239) was balanced for age and diagnosis, resulting in n=181 female adolescents (average age=14.09 years), diagnosed with AN (n=61), BN (n=60) and BED (n=60).

The families were 93.92% Caucasian, and most of the families (88.95%) had a middle–middle/middle–high socioeconomic level according to the Hollingshead’s social status index.Citation51 A large majority (92.82%) of families were intact family groups and lived with both parents. In all, 87% of adolescents were first-born children for both parents.

Procedure

The research described here was approved by the ethics committee of the Psychology Faculty at Sapienza, University of Rome, before the start of the study and was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. After the first assessment interview and before starting the treatment plan, all adolescents and their families agreed to participate in the study (no attrition was found). All parents signed informed consents, and adolescents gave their assent. Researchers in person administered the self-report questionnaires (described later), and adolescents and their parents filled out the questionnaires independently. Parents and adolescents filled out the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale (FACES), and adolescents also completed the Symptom Checklist-90 Items-Revised (SCL-90-R). All measures were completed at the time of distribution.

Measures

The SCL-90-R is a 90-item self-report symptom inventory designed to measure psychological symptoms and psychological distress.Citation52 The SCL-90-R is rated on a Likert scale of 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) and asks participants to report whether they have suffered in the past week from symptoms that are scored and interpreted in terms of nine dimensions: somatization (SOM; e.g., headaches), obsessive-compulsivity (O-C; e.g., unwanted thoughts, words, or ideas that would not leave your mind), interpersonal sensitivity (I-S; e.g., feeling critical of others), DEP (e.g., loss of sexual interest or pleasure), ANX (e.g., nervousness or shakiness inside), hostility (HOS; e.g., feeling easily annoyed or irritated), phobic anxiety (PHOB; e.g., feeling afraid in open spaces or on the streets), paranoid ideation (PAR; e.g., feeling others are to blame for most of your troubles), and psychoticism (PSY; e.g., the idea that someone else can control your thoughts). Furthermore, it is scored on three global indices of distress, Global Severity Index (GSI), Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI), and Positive Symptom Total (PST). Prunas et alCitation53 demonstrated a satisfactory internal consistency of the Italian version of the SCL-90-R in adolescents and adults (α coefficient, 0.70–0.96). Scores higher than the clinical cut-off (≥1 in GSI) indicate psychopathological risk.

The FACES-IV is a self-report questionnaire that assesses adolescents’ and parents’ perceived family functioning.Citation54 It is composed of 42 items rated on a Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The FACES-IV is scored on six scales: two balanced scales, cohesion and flexibility, assessing central–moderate areas and four unbalanced scales, enmeshed, disengaged, chaotic, and rigidity, assessing the lower and the upper ends of cohesion and flexibility. Higher scores on the balanced scales are linked with higher levels of adaptive family functioning, while higher scores on the unbalanced scales indicate more problematic family functioning. In the present study, reliability of the six FACES-IV scales was as follows: enmeshed=0.78, disengaged=0.86, balanced cohesion=0.87, chaotic=0.85, balanced flexibility=0.84, and rigid=0.85. The α reliability was very good for all six scales.Citation54 In addition, two additional scales within the FACES-IV battery have been included: Family Satisfaction Scale (FSS) and Family Communication Scale (FCS). The FCS is a 10-item scale developed to measure communication in families with an adolescent, which can be used with a variety of family forms, and families at various life-cycle stages related to the Circumplex Model. The internal consistency reliability of the FCS is 0.90 and the test–retest reliability is 0.86. In this study, internal consistency reliability is 0.84. The FSS is a 10-item scale, developed by OlsonCitation55 in relation to the Circumplex Model, and it is intended as a part of FACES-IV. The scale assesses the degree of satisfaction with aspects related to family cohesion and flexibility. The FSS has an alpha reliability of 0.93 and test–retest reliability of 0.85. In this study, internal consistency reliability is 0.91 and we used the normative scores of the Italian version of FACES-IV and family members’ scores were averaged to yield an overall family score.Citation54–Citation56

Statistical analysis

The statistical package SPSS 23.0 was used for all analyses. Adolescents’, mothers’, and fathers’ scores on FACES-IV were coded in accordance with the author’s instructions.Citation54

In order to assess family functioning, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted identifying the groups (Group A: subjects with AN, Group B: subjects with BN, and Group C: subjects with BED) as the independent variables, and all of the dimensions of the FACES-IV were identified as the dependent variables. Families’ scores were compared with the mean scores of the Italian population.

ANOVAs were conducted to verify possible significant differences between the three study groups on adolescents’ psychopathological risk. The post hoc analyses were conducted using the Scheffè’s method. To evaluate the clinical relevance of the scores identified, cutoff values for the Italian population were used. Finally, to evaluate the possible predictive power of family functioning on adolescents’ psychopathological risk in the different groups, a series of hierarchical regressions were conducted, also assessing the possible effects of interaction. Missing data (2% for each instrument) for all applicable analyses were corrected using multiple imputations in the SPSS software (Version 23.0).

Results

Assessment of family functioning

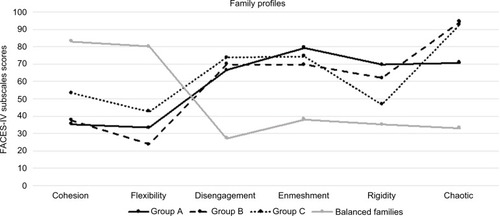

To verify a possible significant difference on family functioning in families with adolescents diagnosed with AN, BN, and BED, an ANOVA was conducted considering the mean scores in the perception of family functioning of fathers, mothers, and adolescents on FACES-IV in Groups A, B, and C. shows family functioning profiles of families with adolescents diagnosed with different EDs.

Figure 1 Family profiles of families with adolescents affected by AN (Group A), BN (Group B), and BED (Group C).

As it is possible to see, there are differences in family profiles between the three diagnostic groups. Furthermore, all family profiles diverge from the profile identified by OlsonCitation55 for balanced families. lists significant differences between the mean scores of the three groups and those of balanced families.

Table 1 Differences between the mean scores of the three groups (Group A: AN, Group B: BN, and Group C: BED) and those of balanced families

Results of ANOVA showed that families with adolescents diagnosed with AN (Group A) showed higher scores than other groups on FACES-IV subscales enmeshment (p<0.001) and rigidity (p<0.001 compared to Group C; p<0.05 compared to Group B) and lower scores on subscales cohesion (p<0.001, compared to Group C), communication (p<0.001, compared to Group C), and chaotic (p<0.001, compared to other groups). Families with adolescents diagnosed with BN (Group B), instead, had higher scores on chaotic (p<0.001) than Group A and lower scores on cohesion (p<0.001, compared to Group C) and flexibility (p<0.001) compared to other groups. Furthermore, families with adolescents diagnosed with BEDs (Group C) had higher scores on cohesion (p<0.001), flexibility (p<0.001), and communication (p<0.001) than Groups A and B.

Assessment of adolescents’ psychopathological risk

To verify a possible significant difference in the scores of adolescents’ psychopathological risk in the three study groups, an ANOVA was conducted. Group factor (Group A: subjects with Z, Group B: subjects with BN, and Group C: subjects with BED) was identified as the independent variable and all SCL-90-R subscales were identified as the dependent variables. Results showed significant differences between groups on psychopathological profiles ().

Table 2 Means, standard deviations, and cutoff values of adolescents’ scores on SCL-90-R (Group A: adolescents with AN, Group B: adolescents with BN, and Group C: adolescents with BED)

Results showed that adolescents of Groups A, B, and C had specific characteristics in their psychopathological profiles. In particular, adolescents diagnosed with AN had the highest psychopathological risk. Moreover, adolescents of Group A showed mean scores that exceeded the clinical cutoff in all SCL-90-R subscales and had higher scores on subscales ANX (p<0.001, compared to Group C), O-C (p<0.001), DEP (p<0.001), HOS (p<0.001), and GSI (p<0.01) if compared to other groups. On the other hand, adolescents of Group B showed higher scores on SOM (p<0.001), PAR (p<0.001), and PHOB (p<0.001) than other groups and exceeded clinical cutoff in these subscales. Furthermore, adolescents of Group C showed higher scores on I-S (p<0.001) and PSY (p<0.001) compared to Groups A and B and exceeded clinical cutoff in these subscales.

Associations between family functioning and adolescents’ psychopathology

A series of hierarchical regressions were conducted to evaluate the possible associations between family functioning and adolescents’ psychopathology. Results showed that family functioning is associated with adolescents’ psychopathological risk, differently in the three groups. Regression analysis on Group A showed that higher scores on the FACES-IV subscale rigidity predicted higher scores on adolescents’ SOM (R2=0.224; β=0.303; t=2.24; p<0.05), and higher scores on FACES-IV subscale enmeshment predicted higher scores on adolescents’ ANX (R2=0.29; β =0.37; t=2.57; p<0.05). Furthermore, regression analysis on Group B showed that higher scores on FACES-IV subscale rigidity predicted higher scores on adolescents’ DEP (R2=0.202; β =0.45; t=2.64; p<0.05) and that lower scores on communication predicted higher scores on I-S (R2=0.26; β =−0.45; t=−3.04; p<0.01) and lower scores on satisfaction predicted higher scores on HOS (R2=0.26; β =−0.32; t=−2.21; p<0.05). Finally, the regression analysis on Group C showed that higher scores on FACES-IV subscale rigidity predicted higher scores on I-S (R2=0.19; β =0.34; t=2.21; p<0.05).

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the possible associations between family functioning and psychopathological symptoms in adolescents with EDs. We aimed to verify the existence of specific profiles of family functioning and specific psychopathological symptoms in adolescents diagnosed with AN, BN, and BED. Our results showed that families of female adolescents with EDs are characterized by specific problematic profiles of family functioning. As shown in , all family profiles diverge from the profile identified by OlsonCitation57 for balanced families, which showed higher levels of cohesion and flexibility and lower scores on the subdimensions of disengagement, enmeshment, rigidity, and chaotic. Moreover, there are significant differences between family profiles in the three diagnostic groups. In particular, families with adolescents diagnosed with AN tend to report interpersonal boundary problems, poor tolerance of conflicts, and low levels of general satisfaction in their family. Specifically, they showed significantly higher scores of enmeshment and rigidity and lower scores of cohesion, chaotic, and communication quality. These results are consistent with previous studies that indicated the presence of excessive dependence on other family members, low flexibility, poor communication, and overprotectiveness in these families.Citation18,Citation58 These features seem to be coherent with conflict avoidance, which generally characterizes familial relationship of families with daughters diagnosed with AN.Citation59

Parents of adolescents diagnosed with BN described their families as more chaotic than parents in families with adolescents diagnosed with AN, with lower levels of flexibility and cohesion than all other groups. In addition, Vidović et alCitation60 suggested that families of adolescents with bulimic diagnosis have a significantly more dysfunctional family background compared to patients diagnosed with AN. The families of bulimic adolescents represented their families as less cohesive, poorly coherent, and badly organized and reported the presence of high levels of family conflict and distress.Citation46,Citation61 Finally, families of adolescents diagnosed with BED showed higher scores of cohesion and flexibility, and similar to families with daughters suffering from AN, they described their family as enmeshed and characterized by poor communication. These findings are coherent with the study of Tetzlaff et alCitation37 that has suggested that families of female adolescents with BED showed significantly low emotional and affective involvement; other studies also underlined that they tend to report nonaffective communication and low adaptability.Citation62

With regard to adolescents’ psychopathological risk, our study found that Groups A, B, and C presented specific psychopathological profiles. In particular, adolescents with AN reported the highest levels of psychopathological risk, exceeding the clinical cutoffs for the Italian population in all SCL-90-R subscales, and they reported greater obsessive–compulsive symptomatology, DEP, HOS, and ANX. Adolescents with BN (Group B) showed more difficulties on SOM and PHOB. On the other hand, adolescents suffering from BED had higher scores of I-S and PSY. Our results are in line with international scientific literature that underlines that adolescents suffering from an ED can present a wide range of subclinical forms of psychological problems, specifically in the internalizing area.Citation21,Citation22,Citation63 Results also showed that families with adolescents diagnosed with AN, BN, and BED had different profiles of family functioning and that their daughters showed psychopathological risk in different problematic areas. Thus, we aimed to verify the possible association of family functioning with adolescents’ psychopathological risk. Regression analysis confirmed this association. In particular, as previously found by Allen et al,Citation64 in adolescents with AN, higher rigidity in familial relationship predicts higher levels of SOM, whereas higher enmeshment is predictive of higher ANX. In adolescents with BN, higher levels of rigidity are associated with higher scores of DEP, poorer quality of communication predicts higher scores of I-S, and lower levels of satisfaction are associated with higher scores of I-S. Finally, higher scores of rigidity in families with adolescents with BED are predictive of higher levels of I-S. These results are consistent with the findings of one previous study that have suggested that dysfunctional family functioning is associated with a higher psychopathological risk in adolescents with EDs.Citation65 Interestingly, our results also showed that rigidity, which characterizes family functioning in families with daughters with EDs, predicts higher psychopathological symptoms, but with different configurations in the three diagnostic groups. Everri et alCitation66 underlined that when rigidity is associated with disengagement, low cohesion and flexibility could be considered as maladaptive. Furthermore, Lampis et alCitation67 have shown that high levels of cohesion and family adaptability were protection factors for EDs.

The present study has several strengths. First, the study took into consideration three groups of adolescents diagnosed with different EDs, assessing adolescents’ psychopathological risk and family functioning. Second, the measures used are well validated and are widely used.Citation52,Citation54 Third, our research assesses parents’ and adolescents’ perceived quality of family functioning, considering mean scores aggregating the scores of family members, which may constitute a strong stimulus for further clinical studies. Studies addressing specific forms of EDs and their associations with psychopathological profiles and family functioning are scarce. The present study may add to previous literature and supports clinical work in the treatment of adolescents diagnosed with EDs, as suggested by Jewell et al.Citation68 In fact, clinicians could organize different interventions depending on the particular ED the adolescent is manifesting and the specific familial functioning (represented for instance by their members’ capacity to adaptively communicate, support each other, and be flexible).

Our study has some limitations. We did not recruit a control sample, and it has not been possible to compare subjects’ scores to a nonclinical group. On the other hand, we used the normative scores for the Italian population for both measures. Furthermore, we did not assess parental psychopathological risk, which could give important information on the development of adolescents’ EDs.Citation46,Citation69–Citation71 In addition, the homogeneity of the sample, in terms of cultural, geographical, and socioeconomic status, limits replication of the study in other countries or cultures. Finally, the present study did not take into consideration social support, which several studies underline to be important in the adolescent phase,Citation72,Citation73 and longitudinal studies are needed that can clarify the many dynamics.Citation74,Citation75

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- LevineMSmolakLToward a model of the developmental psychopathology of eating disorders: the example of early adolescenceCrowterJHHobfollSEStephensMATennenbaumDLThe Etiology of Bulimia Nervosa: The Individual and Familial ContextWashingtonTaylor and Francis20135980

- TafàMBaioccoRAddictive behavior and family functioning during adolescenceJ Fam Ther200937388395

- AmiantoFErcoleRMarzolaEAbbate DagaGFassinoSParents’ personality clusters and eating disordered daughters’ personality and psychopathologyPsychiatry Res20152301192726315665

- VisaniEStudi sul funzionamento familiare: osservazioni complessiveVisaniEDi NuovoSLoriedoCFaces IV Il ModelloCirconflesso di Olson nella clinica e nella ricercaMilanoFranco Angeli2014148152

- KlumpKLPuberty as a critical risk period for eating disorders: a review of human and animal studiesHorm Behav201364239941023998681

- Brooks-GunnJPubertal processes and girls’ psychological adaptationLernerRFochTTBiological-Psychosocial Interactions in Early Adolescence: A Life-Span PerspectiveHillsdale, NJLawrence Erlbaum Associates1987123153

- PacielloMFidaRTramontanoCColeECernigliaLMoral dilemma in adolescence: the role of values, prosocial moral reasoning and moral disengagement in helping decision makingEur J Dev Psychol2013102190205

- MonacisLde PaloVGriffithsMDSinatraMExploring individual differences in online addictions: the role of identity and attachmentInt J Ment Health Addict201715485386828798553

- PatelPWheatcroftRParkRJSteinAThe children of mothers with eating disordersClin Child Fam Psychol Rev2002511911993543

- SteinbergLDAdolescence5th edNew YorkMcGraw-Hill1999

- CernigliaLCiminoSBallarottoGMotor vehicle accidents and adolescents: an empirical study on their emotional and behavioral profiles, defense strategies and parental supportTransp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav2015352836

- PoppeISimonsAGlazemakersIVan WestDEarly-onset eating disorders: a review of the literatureTijdschr Psychiatr2015571180581426552927

- SwansonSACrowSJLe GrangeDSwendsenJMerikangasKRPrevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents: results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplementArch Gen Psychiatry201168771472321383252

- HayPGirosiFMondJPrevalence and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-5 eating disorders in the Australian populationJ Eat Disord201531925914826

- SepulvedaARCarroblesJAGandarillasAMGender, school and academic year differences among Spanish University students at high-risk for developing an eating disorder: an epidemiologic studyBMC Public Health2008288102

- SminkFRvan HoekenDOldehinkelAJHoekHWPrevalence and severity of DSM-5 eating disorders in a community cohort of adolescentsInt J Eat Disord201447661061924903034

- SidorABabaCOMarton-VasarhelyiECherechesRMGender differences in the magnitude of the associations between eating disorders symptoms and depression and anxiety symptoms. Results from a com-munity sample of adolescentsJ Ment Health201524529429826288326

- BergeJMLothKHansonCCroll-LampertJNeumark-SztainerDFamily life cycle transitions and the onset of eating disorders: a retrospective grounded theory approachJ Clin Nurs2012219–101355136321749510

- StroberMKatzJLDepression in the eating disorders: a review and analysis of descriptive, family and biological findings Diagnostic issues in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosaGarnerDMGarfinkelPEDiagnostic Issues in Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia NervosaNew YorkBrunner/Mazel198880111

- PopeHGHudsonJIAre eating disorders associated with borderline personality disorder? A critical reviewInt J Eat Disord1989819

- SticeEMartiCNDurantSRisk factors for onset of eating disorders: evidence of multiple risk pathways from an 8-year prospective studyBehav Res Ther2011491062262721764035

- LucarelliLCiminoSD’OlimpioFAmmanitiMFeeding disorders of early childhood: an empirical study of diagnostic subtypesInt J Eat Disord201346214715523015314

- TambelliRCernigliaLCiminoSAn exploratory study on the influence of psychopathological risk and impulsivity on BMI and perceived quality of life in obese patientsNutrients20179511

- Thompson-BrennerHEddyKTSatirDABoisseauCLWestenDPersonality subtypes in adolescents with eating disorders: validation of a classification approachJ Child Psychol Psychiatry200849217018018093115

- MonellEHögdahlLForsén MantillaEBirgegårdAEmotion dysregulation, self-image and eating disorder symptoms in University WomenJ Eat Disord201534426629343

- ParolinMSimonelliACristofaloPDrug addiction and emotional dysregulation in young adultsHeroin Addict Relat Clin Probl20171933748

- Gilboa-SchechtmanEAvnonLZuberyEJeczmienPEmotional processing in eating disorders: specific impairment or general distress related deficiency?Depress Anxiety200623633133916688732

- KendlerKSAggenSHKnudsenGPRøysambENealeMCReich-born-KjennerudTThe structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for syndromal and subsyndromal common DSM-IV axis I and all axis II disordersAm J Psychiatry20111681293920952461

- BaboreATrumelloCCandeloriCPacielloMCernigliaLDepressive symptoms, self-esteem and perceived parent-child relationship in early adolescenceFront Psychol2016798227445941

- CernigliaLZorattoFCiminoSLaviolaGAmmanitiMAdrianiWInternet addiction in adolescence: neurobiological, psychosocial and clinical issuesNeurosci Biobehav Rev201776pt A17418428027952

- EcclesJSMidgleyCWigfieldADevelopment during adolescence: the impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in familiesAm Psychol1993482901018442578

- O’ConnellMEBoatTWarnerKEPreventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders among Young People: Progress and PossibilitiesWashington, DCThe National Academic Press2009

- BergeJMWallMLarsonNEisenbergMELothKANeumark-SztainerDThe unique and additive associations of family functioning and parenting practices with disordered eating behaviors in diverse adolescentsJ Behav Med201437220521723196919

- WisotskyWDancygerIFornariVKatzJWisotskyWLSwencionisCThe relationship between eating pathology and perceived family functioning in eating disorder patients in a day treatment programEat Disord2003112899916864512

- le GrangeDLockJLoebKNichollsDAcademy for Eating Disorders position paper: the role of the family in eating disordersInt J Eat Disord20104311519728372

- LykeJMatsenJFamily functioning and risk factors for disordered eatingEat Behav201314449749924183144

- TetzlaffASchmidtRBrauhardtAHilbertAFamily functioning in adolescents with binge-eating disorderEur Eat Disord Rev20162443043327426991

- EislerIThe empirical and theoretical base of family therapy and multiple family day therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosaJ Fam Ther2005272104131

- MinuchinSFishmanHCPsychosomatic family in child psychiatryJ Am Acad Child Psychiatry19801817690

- MinuchinSRosmanBLBakerLPsychosomatic Families: Anorexia Nervosa in ContextCambridge, MAHarward University Press1978

- WoodBWatkinsJBBoyleJTNogueiraJZimandECarrollLThe “Psychosomatic Family” Model: an empirical and theoretical analysisFam Process1989283994172599066

- DareCGrangeDLEislerIRutherfordJRedefining the psychosomatic family: family process of 26 eating disorder familiesInt J Eat Disord19941632112267833955

- OlsonDHFamily assessment and intervention: the Circumplex Model of family systemsChild Youth Serv198811948

- FrankoDLThompsonDAffenitoSGBartonBAStriegel-MooreRHWhat mediates the relationship between family meals and adolescent health issuesHealth Psychol2008272S109S11718377152

- KivistoKLWelshDPDarlingNCulpepperCLFamily enmeshment, adolescent emotional dysregulation, and the moderating role of genderJ Fam Psychol201529460461326374939

- TafàMCiminoSBallarottoGBracagliaFBottoneCCernigliaLFemale adolescents with eating disorders, parental psychopathological risk and family functioningJ Child Fam Stud20162612839

- FeethamSLFeetham Family Functioning SurveyWashington, DCChildren’s Hospital National Medical Center1988

- LanzMRosnatiRMetodologia della ricerca sulla famigliaMilanoLed2002

- MazzoniSTafàMMethodological problems for the study of family realtionships [Problemi metodologici nello studio delle relazioni familiari]MazzoniSTafàMIntersubjectivity in the family Multimethod procedures for the observation and assessment of family relationships [L’intersoggettività nella famiglia Procedure multimetodo per l’osservazione e la valutazione delle relazioni familiari]MilanoFranco Angeli20075366

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)Arlington, VAAmerican Psychiatric Publishing2013

- HollingsheadABFour Factor Index of Social StatusNew Haven, CTYale University1975

- DerogatisLRSymptom Checklist-90-Revised: Administration, Scoring and Procedures ManualMinneapolis, MNNational Computer Systems1994

- PrunasASarnoIPretiEMadedduFPeruginiMPsychometric properties of the Italian version of the SCL-90-R: a study on a large community sampleEur Psychiatry201227859159721334861

- OlsonDHFACES IV and the Circumplex Model: validation studyJ Marital Fam Ther2011371648021198689

- OlsonDHFamily Satisfaction ScaleMinneapolis, MNLife Innovations1995

- BaioccoRCacioppoMLaghiFTafàMFactorial and construct validity of FACES IV among Italian adolescentsJ Child Fam Stud201322962970

- OlsonDHData Analysis Using FACES IV ScoresMinneapolis, MNLife Innovations2010

- ErolAYaziciFToprakGFamily functioning of patients with an eating disorder compared with that of patients with obsessive compulsive disorderCompr Psychiatry2007481475017145281

- Holtom-VieselAAllanSA systematic review of the literature on family functioning across all eating disorder diagnoses in comparison to control familiesClin Psychol Rev2014341294324321132

- VidovićVJurešaVBegovacIMahnikMTociljGPerceived family cohesion, adaptability and communication in eating disordersEur Eat Disord Rev20051311928

- JohnsonCFlachAFamily characteristics of 105 patients with bulimia nervosaAm J Psychiatry1985142132113243864383

- MenoCAHannumJWEspelageDEDouglas LowKDFamilial and individual variables as predictors of dieting concerns and binge eating in college femalesEat Behav2008919110118167327

- CernigliaLMuratoriPMiloneAPaternal psychopathological risk and psychological functioning in children with eating disorders and Disruptive Behavior DisorderPsychiatry Res2017254606628456023

- AllenKLGibsonLYMcLeanNJDavisEAByrneSMMaternal and family factors and child eating pathology: risk and protective relationshipsJ Eat Disord201429211

- WisotskyWDancygerIFornariVIs perceived family dysfunction related to comorbid psychopathology? A study at an eating disorder day treatment programInt J Adolesc Med Health200618223524416894862

- EverriMManciniTFruggeriLThe role of rigidity in adaptive and maladaptive families assessed by FACES IV: the points of view of adolescentsJ Child Fam Stud201625102987299727656088

- LampisJAgusMCacciarruBQuality of family relationships as protective factors of eating disorders: an investigation amongst Italian teenagersAppl Res Qual Life20149309324

- JewellTBlessittEStewartCSimicMEislerIFamily therapy for child and adolescent eating disorders: a critical reviewFam Process20165557759427543373

- CernigliaLCiminoSBallarottoGMother-child and father-child interaction with their 24-month-old children during feeding, considering paternal involvement and the child’s temperament in a community sampleInfant Ment Health J201435547348125798497

- TambelliRCiminoSCernigliaLBallarottoGEarly maternal relational traumatic experiences and psychopathological symptoms: a longitudinal study on mother-infant and father-infant interactionsSci Rep201551398426354733

- TambelliRCernigliaLCiminoSBallarottoGParent-infant interactions in families with women diagnosed with postnatal depression: a longitudinal study on the effects of a psychodynamic treatmentFront Psychol2015621025767458

- CernigliaLCiminoSBallarottoGMonnielloGParental loss during childhood and outcomes on adolescents’ psychological profiles: a longitudinal studyCurr Psychol2014334545556

- CernigliaLCiminoSBallarottoGTambelliRErratum to: do parental traumatic experiences have a role in the psychological functioning of early adolescents with binge eating disorder?Eat Weight Disord201722237728244032

- CapobiancoMPizzutoEADevescoviAGesture speech combinations and early verbale abilities. New longitudinal data during the second year of ageInteract Stud20171815475

- CiminoSCernigliaLPorrecaASimonelliARonconiLBallarottoGMothers and fathers with binge eating disorder and their 18–36 months old children: a longitudinal study on parent–infant interactions and offspring’s emotional–behavioral profilesFront Psychol2016758027199815