Abstract

Purpose

A growing number of studies have explored the psychosocial burden experienced by cancer caregivers, but less attention has been given to the psychophysiological impact of caregiving and the impact of caregivers’ coping strategies on this association. This paper reviews existing research on the processes underlying distress experienced by cancer caregivers, with a specific focus on the role of coping strategies on psychophysiological correlates of burden.

Methods

A broad literature search was conducted in health-related databases namely MEDLINE, Science Citations Index Expanded, Scopus, and PsycINFO, using relevant search terms. All types of studies published in English were considered for inclusion.

Results

We found that cancer caregiving was related to increased blood pressure, dysregulation of autonomic nervous system, hypothalamic–pituitary–axis dysregulation, immune changes, and poor health-related behaviors. We also found that problem-focused coping was associated with decreased caregiver burden, decreased depression, and better adjustment, while emotion-focused coping was related to higher levels of posttraumatic growth and psychological distress. The way coping impacts psychophysiological correlates of burden, however, remains unexplored.

Conclusion

A better understanding of the psychophysiological elements of caregiver burden is needed. We propose a model that attends specifically to factors that may impact psychophysiological correlates of burden among cancer caregivers. Based on the proposed model, psychosocial interventions that specifically target caregivers’ coping and emotion regulation skills, family functioning, and self-care are endemic to the preservation of the health and well-being of this vulnerable population.

Background

Throughout history, the provision of informal care by family members and friends has been a critical avenue for the protection of individuals with chronic health problems.Citation1 Caregivers have always held significant socioeconomic value in society, one that will likely increase exponentially in the future as the number of individuals with chronic medical illnesses continues to rise. For example, the annual economic value of informal caregiving (i.e., providing care to a loved one with a chronic medical illness without being compensated financially to do so) in the USA was recently estimated at $375 billion.Citation2

While the negative impact of caregiving has been widely documented, much less attention has been given to ways in which such negative outcomes may be avoided.Citation3 The objective of this review was to examine the role of coping strategies on dimensions of stress and negative health outcomes, with a specific focus on psychophysiological correlates of burden among cancer caregivers. Since psychological adjustment to cancer is a dynamic process that depends in part on the meaning attributed to the illness and coping strategies employed to face emotional exhaustion and perceived lack of control, a greater understanding of caregivers’ coping strategies will directly inform the development of empirically supported interventions that attend to the unique psychological symptoms of burden experienced by cancer caregivers.Citation3,Citation4

Caregiver burden

A large body of literature suggests that providing care to a chronically ill loved one has the potential to cause caregiver burden. Specifically, cancer has the potential to significantly and negatively impact patients and their informal caregivers, for whom the disease trajectory represents a significant source of distress and burden.Citation5 According to the Oncology Nursing Society,Citation6 caregiver burden encompasses the difficulties of the caregiver role and the associated alterations in caregivers’ emotional and physical health that can occur when care demands exceed resources. Caregivers experience varying challenges during different phases of the cancer trajectory that can significantly impact their functioning and quality of life. Indeed, close to one-half of caregivers of patients with advanced cancer have some symptoms of distress (e.g., depression, anxiety, insomnia, and decreased quality of life).Citation7 Moreover, family members significantly involved in the patient’s care, and who report a significant impact of caregiving on their daily activities, often report fatigue and burden associated with the patient’s cognitive and physical dysfunction.Citation8,Citation9 Additionally, in families of patients at end of life, caregivers face the dual challenge of providing care and beginning to process anticipatory grief. These concerns are well recognized by health organizations that consider the patient and family as a unit of care, and offer support during the disease trajectory, from diagnosis to bereavement.Citation10–Citation12

Emotional burden

While rates of psychopathology are high among patients with cancer – higher than rates in the general population – new data suggest that the rates are even higher among their caregivers. For example, several reviews and meta-analyses have demonstrated a higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders, especially anxiety and depressive disorders, in caregivers when compared with individuals in the general population.Citation13–Citation17 Depression, in particular, has emerged as a primary focus of research. A literature review found that an estimated 20%–73% of cancer caregivers experience depressive symptomatology, rates that are higher than those in the general population.Citation18 Importantly, depression has been found to be associated with specific factors, including caregivers demographic characteristics (i.e., younger age, female gender, and spousal relationship with care recipient), negative appraisals of caregiving demands, and inadequate support received by the cancer caregiver.Citation5,Citation19,Citation20 Moreover, the responsibility to fulfill roles in addition to cancer care, such as employment or childcare, may lead to greater emotional or psychological distress among caregivers.Citation21 Lack of time, financial burden, and reduced income are also apparent among family members providing care to patients with cancer.Citation22–Citation24

Physical burden

While emotional aspects of caregiver burden have been thoroughly evaluated and documented, considerably less research has explored physical burden and psychophysiological correlates of such burden among caregivers. Caregivers are at risk of a range of physical health complications as a result of their role.Citation25–Citation27 These include sleep difficulties,Citation28–Citation30 fatigue,Citation8,Citation31 cardiovascular disease,Citation32,Citation33 poor immune functioning,Citation34,Citation35 and increased mortality.Citation36,Citation37 For example, Schulz and BeachCitation36 found that caregivers who reported burden had a 63% increased risk of mortality when compared with noncaregivers. In addition, these caregivers were much less likely to have time to rest when sick, time to exercise, or to secure adequate rest to allow for optimal caregiving capacity. Studies have also reported poor health-related behaviors, such as increased alcohol and tobacco use.Citation38,Citation39 In fact, some studies indicate that caregivers are less likely to undertake preventive health behaviors and generally exhibit decreased health care service utilization.Citation40

Positive outcomes of caregiving

Although a majority of studies have highlighted the negative outcomes of caregiving, some positive outcomes of caregiving have also been reported. Recent systematic reviews have identified positive aspects in informal caregiving. These include improved mood, better relationship satisfaction, personal growth, competence and mastery, better subjective well-being, and even better cognitive functioning and lower mortality.Citation41,Citation42 Using a diary methodology, Cheng et alCitation43 found that Alzheimer caregivers were capable of identifying several positive gains within this process, such as a sense of purpose, feelings of gratification, increased tolerance, or even cultivation of positive meanings. In the specific context of cancer, caregiving was also associated with positive experiences. In two recent systematic reviews, caregivers reported feelings of being rewarded, personal growth, and finding meaning, personal satisfaction and discovery of personal strength, and improved their relationship, not only with the care-receiver, but also within other relationships.Citation44,Citation45

This review

The purpose of this review was to provide an extensive overview of the state of literature in relation to the psychophysiological consequences of caregiving and the role of coping strategies on this association. To that end, we first review the status of the relationship between caregiving and psychophysiological stress responses, and the association between coping and psychophysiological correlates of burden. Based on our findings and on previous models, we propose a model to guide research within this field. We conclude by outlining potential lines of inquiry for future research.

Methodology

A broad literature search on the processes underlying distress experienced by cancer caregivers, with a specific focus on the impact of coping strategies on psychophysiological correlates of burden was conducted using several databases, namely MEDLINE, Science Citation Index Expanded, Scopus, and PsycINFO. To this end, keywords such as “cancer”, “oncology”, “caregiver”, “caregiving”, “carer”, “coping”, or “coping strategies”, “burden”, “physiology”, “distress” were used. All types of studies (e.g., quantitative, qualitative), published in English, assessing 1) psychophysiological stress responses in the context of caregiving and 2) the association between coping strategies and psychophysiological correlates of burden in samples of cancer caregivers were included.

Results

A total of 30 articles were identified. From these, four articles exploring the link between caregiving and psychophysiological stress responses and five articles exploring the association between coping strategies and psychophysiological correlates were included in this review. Study characteristics and main results are presented in and . Given the lack of studies found, results from included studies were also related to studies from other caregiving contexts and from the broad psychophysiological literature to better understand the results obtained in the context of cancer caregiving.

Table 1 Study characteristics and main results of included studies for associations between caregiving and psychophysiological stress responses (N=4)

Table 2 Study characteristics and main results of included studies for associations between coping strategies and psychophysiological correlates (N=5)

Caregiving and psychophysiological stress responses

Although certain physiological responses (e.g., increase in cardiovascular function and a release of adrenal catecholamines) are anticipated and considered adaptive during the initial reaction to an acute stressorCitation46 such as the diagnosis of cancer in oneself or a loved one,Citation39 a period of chronic stress – such as that experienced during the cancer caregiving trajectory – can lead to changes in cardiovascular and immune functioning that are no longer adaptive, but instead have the potential to compromise the physical well-being of the caregiver. In their review, Weitzner et alCitation47 found that when faced with demanding care situations, cancer caregivers present a lowered immune system functioning, an increase in blood pressure, and altered lipid profiles, leading to a state of enhanced psychological morbidity and burden. In another study, Lucini et alCitation48 evaluated the effects of caregiving as a risk factor for poor health in caregivers of cancer patients and noncaregivers. The study included the investigation of psychological and physiological (autonomic nervous system) measures. The results indicated that cancer caregivers showed dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system, which was attributed to stressors associated with caregiving. The experience of stress led to an activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–axis (HPA) and immune changes, as well as behavioral alterations such as adoption of poor health-related behaviors. The results revealed that since cancer caregivers had higher levels of stress, and an obvious autonomic imbalance, there was a reduction in cardiac vagal regulation, which significantly compromised their health status. This result, as well as others reported by Teixeira and Pereira,Citation49 suggests the need to carry out preventive strategies to improve the autonomic profile of cancer caregivers. For example, decreased immune functioning may occur as a result of diminished cytokine production (considered mediators and regulators of innate immunity), eventually compromising the body in relation to the ability to cope with a disease.Citation50,Citation51

Recent research has begun to identify mechanisms through which the caregiving experience impacts health outcomes. Previous reviewsCitation52 have identified several potential mechanisms, including the ability to regulate psychophysiological responses to environmental challenges. For example, psychophysiological stress responses prepare the body to survive physical threats by mobilizing stored energy, increasing cardiac output, and suppressing nonessential digestive, immune, and reproductive functions.Citation46 At a psychophysiological level, research also suggests that the combination of prolonged stress and physical demands of caregiving can compromise the physiological functioning of caregivers and increase the risk of health problems.Citation53,Citation54 As Luecken and Lemery’s studyCitation55 suggests, caregiving may be associated, in the long term, with dysregulated physiological stress responses and, ultimately, disease outcomes. Beyond the genetic and the psychosocial pathways, Davies and Cummings reflect on a cognitive-affective pathway, suggesting that caregiving experiences influence the development of cognitive and emotional self-regulatory abilities and threat appraisals, which can then alter subsequent responses to stress. In fact, affective self-regulation has been linked with improved coping with daily stressors,Citation56 lower levels of aggression and hostility,Citation57 and improved health-related behaviors.Citation58 Therefore, the manner in which individuals make sense of situations has the potential to impact both behavioral and physiological responses.

Coping and psychophysiological correlates of burden

Similar to the dearth of studies that systematically examine the impact of specific coping strategies on psychological outcomes, very little attention has been given to the impact of caregivers’ coping strategies on psychophysiological correlates of burden.Citation59 For example, problem-focused coping has been associated with decreased caregiver burden,Citation60 while problem-solving ability of the caregiver of a physically disabled family member has been found to predict improved adjustment and decreased depression.Citation61 Additionally, emotion-focused coping has been associated with higher levels of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and general psychological distress in parents of children with cancer and diabetes.Citation62 When coping styles were investigated longitudinally among cancer caregivers, problem-focused coping was most effective at the time of diagnosis, a point which requires learning about the illness and exploring treatment options.Citation63 The same study also revealed that coping styles shifted as treatment progressed, and that previous coping styles did not necessarily impact later level of distress. There is also evidence that coping styles can act as a buffer for depression in cancer caregivers. For example, Schumacher et alCitation64 found that caregivers’ perceptions of the efficacy of their coping strategies mediated the relationship between strain and depression. However, when compared with other dimensions of the cancer caregiving context such as stress or depression, coping has remained relatively unexplored.

Discussion

Given the vast literature documenting caregiver burden and the multiply determined nature of such burden, the field of psychooncology is increasingly turning its attention to coping and how mental health professionals may help cancer caregivers to cope with the many demands they face. Indeed, the growing recognition of the critical role that informal caregivers play in our health care systems has been met with equal attention by researchers and government agencies alike on ways in which the health and well-being of cancer caregivers can be maintained.

This integrative review provides evidence of the lack of studies exploring the association between caregiving and psychophysiological outcomes and examining the role of coping on these associations. Yet, some evidence was gathered regarding the impact of caregiving on blood pressure, HPA function, immune function, and health-related behaviors. Moreover, coping strategies used by cancer caregivers seem to influence their psychosocial adaptation and, consequently, may affect their psychophysiological outcomes.

To better understand the experience of cancer caregivers, several models have been proposed ().Citation65–Citation67

Table 3 Models for understanding the experience of cancer caregivers

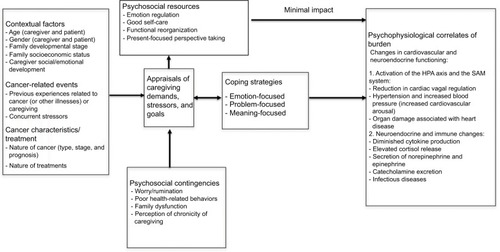

In light of the literature reviewed here and the fact that the previous modelsCitation22,Citation40,Citation69–Citation71 do not specifically attend to psychophysiological indicators of burden, we propose an explanatory model that accounts for this important element of the caregiving experience (). Contextual factors (e.g., age, gender, family variables, and emotional development), cancer-related events of the caregiver (previous caregiving experiences and other stressors), and disease characteristics and treatments (i.e., nature of the cancer and treatments) may impact the way caregivers make sense of a situation in terms of demands, stressors, and goals (i.e., cognitive reappraisal) as well as the way they think about the presence or absence of internal and external resources to meet these demands, stressors, and goals. This cognitive appraisal informs the experience of burden, as indicated via psychophysiological mechanisms. Specifically, such burden may manifest as an activation of the HPA axis and the sympathetic adrenomedullary system (i.e., reduction in cardiac vagal regulation and increased blood pressure), or neuroendocrine and immune changes, such as diminished cytokine production and elevated release of cortisol. These psychophysiological responses, however, can be modulated by caregivers’ coping strategies and specific psychosocial variables. Some authorsCitation57,Citation72,Citation73 have proposed that effectiveness of coping strategies and, specifically, cognitive appraisals, are linked to psychophysiological reactivity to stress, with negative appraisals being associated with increased cardiovascular reactivity.

Figure 1 A proposed model of the impact of coping strategies of cancer caregivers on psychophysiological indicators of burden.

For this reason, we propose that the extent of psychophysiological dysregulation experienced by caregivers is impacted by the use of targeted coping strategies (problem-, emotion-, and meaning-focused) previously described, as well as caregivers’ engagement in optimal emotion regulation strategies (vs. worry, rumination) and self-care (vs. poor health-related behaviors), the existence of family function (vs. dysfunction), and capacity to maintain a present focus (vs. becoming overwhelmed with the perception of the chronicity of the caregiving trajectory). These factors together will impact caregivers’ appraisals of the situation (in terms of perceived harm and threat and capacity to overcome these limitations) and hence, the psychophysiological outcomes experienced.

Future directions

It is clear that psychosocial interventions that target the unique needs of cancer caregivers are needed. In particular, this review highlights the potential benefits of interventions that attend not only to symptoms of burden, but also the mechanisms underlying such symptom profiles. Importantly, our proposed model suggests multiple avenues for intervention, including the facilitation of improved coping strategies, improved emotion regulation skills, self-care, and family functioning.

The present review suggests that, since coping strategies can be learned, interventions that target and provide psychoeducation about coping and adaptive strategies can be useful in preventing and/or decreasing burden, both as measured via subjective rating scales and physiological measurement tools. Drawing on the work of Lazarus and FolkmanCitation68 and Folkman,Citation74 interventions that help caregivers to identify elements of the current caregiving-related challenges that are controllable or uncontrollable, and that teach problem-focused, emotion-focused, and meaning-focused skills have the potential to promote resilience and buffer distress and burden. Indeed, two systematic reviews of psychosocial interventions for cancer caregiversCitation75,Citation76 highlighted the significant benefits of problem-solving and skills building interventions in assisting caregivers with carrying out their responsibilities and cultivating a sense of mastery and control. These reviews – in addition to the earlier reviews of Northouse et alCitation77,Citation78 – also emphasized a dearth of interventions that target specific domains of caregiver needs, such as existential distress and insomnia.

Interventions that attend to caregivers’ emotion regulation skills and ability to manage negative emotions in a healthful way are also critical in light of the expected emergence of negative emotions across the caregiving trajectory. One such intervention, Emotion Regulation Therapy (ERT), originally developed by Mennin and FrescoCitation79 to address worry and rumination in individuals in the general population is currently being adapted to address the processes that underlie anxiety and mood symptoms among cancer caregivers (Emotion Regulation Therapy for Cancer Caregivers; ERT-C). Preliminary analyses have demonstrated strong effects of the ERT-C on rumination, worry, intolerance of uncertainty, and anxious and depressive symptomatology among cancer caregivers.Citation80,Citation81

Importantly, longitudinal studies that examine the experience of caregivers across the caregiving trajectory, from diagnosis to bereavement, and through survivorship, are needed to provide a clearer understanding of the progress of psychological well-being and coping processes of caregivers. Such studies have the potential to highlight critical points, such as diagnosis or relapse, at which distress among caregivers is likely to increase, and in so doing, clearly define critical time points for optimal psychotherapeutic intervention. Studies that examine the unique needs of caregivers of patients with specific types of cancer (e.g., brain tumors) or undergoing specific treatment regimens (e.g., hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation) are also needed so that interventions may target the unique burden experienced by these groups. Work is already underwayCitation82 to develop such interventions for hematopoietic-stem-cell-transplant caregivers. Additionally, studies that examine the impact of life and developmental stage on the caregiving experience will allow for a greater understanding of the context of burden among caregivers.Citation83,Citation84 This, in turn, may highlight variable approaches to coping that are particularly consonant with certain stages in life.

Most critically, systematic study of the psychophysiological correlates of burden is needed in order to understand the broad impact of caregiving on the caregiver. As cancer caregivers themselves represent a population at risk of cancer and other chronic medical illnesses, such attention is critical in order to mitigate the impact of caregiving stress on this vulnerable population.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- LebelSTrinkausEFaureMComparative morphology and paleobiology of Middle Pleistocene human remains from the Bau de l’AubesierVaucluse, FranceProc Natl Acad Sci USA20019820110971110211553766

- ValuingAARPthe invaluable: The economic value of family caregiving Available from: http://www.aarp.org/relationships/caregiving/info-11-2008/i13_caregiving.htmlExternal2008Accessed March 30, 2014

- FitzellIAPakenhamKIApplication of a stress and coping model to positive and negative adjustment outcomes in colorectal cancer caregivingPsychooncology201019111171117820017113

- KershawTNorthouseLKritprachaCSchafenackerAMoodDCoping strategies and quality of life in women with advanced breast cancer and their family caregiversPsych Health2004192139155

- HaleyWEThe costs of family caregiving: implications for geriatric oncologyCrit Rev Oncol Hematol200348215115814607378

- Oncology Nursing SocietyCaregiver Strain and Burden Available from: http://www.ons.org/practice-resources/pep/caregiver-strain-and-burden2014Accessed March 30, 2014

- ÖstlundWWennman-LarsenAPerssonCGustavssonPWengströmYMental health in significant others of patients dying from lung cancerPsychooncology2010191293719253315

- JensenSGivenBAFatigue affecting family caregivers of cancer patientsCancer Nurs19911441811871913632

- WinninghamMLBarton-BurkeMFatigue in CancerLondonJones and Bartlett Publishers2000

- BiondiMPicardiAClinical and biological aspects of bereavement and loss induced depression: a reappraisalPsychother Psychosom19966552292458893324

- Chentsova-DuttonYShucterSHutchinSDepression and grief reactions in hospice caregivers: from pre-death to 1 year afterwardsJ Affect Disord2002691–3536012103452

- SchulzRBeachSRLindBInvolvement in caregiving and adjustment to death of a spouse. Findings from the Caregiver Health Effects StudyJAMA2001285243123312911427141

- Chentsova-DuttonYShuchterSHutchinSStrauseLBurnsKZisookSThe psychological and physical health of hospice caregiversAnn Clin Psychiatry2000121192710798822

- CochraneJJGoeringPNRogersJMThe mental health of informal caregivers in Ontario: an epidemiological surveyAm J Public Health19978712200220079431291

- KarlinNJRetzlaffPDPsychopathology in caregivers of the chronically ill: personality and clinical syndromesHosp J199510355618606052

- PruchnoRAPotashnikSLCaregiving spouses. Physical and mental health in perspectiveJ Am Geriatr Soc19893786977052754154

- SchulzRO’BrienATBookwalaJFleissnerKPsychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: prevalence, correlates, and causesGerontologist19953567717918557205

- Swore-FletcherBADoddMJSchumacherKLMiaskowskiCSymptom experience of family caregivers of patients with cancerOncol Nurs Forum2008352E23E4419405245

- NijboerCTempelaarRSandermanRTriemstraMSpruijtRJvan den BosGACancer and caregiving: the impact on the caregiver’s healthPsychooncology1998713139516646

- RaveisVHKarusDGSiegelKCorrelates of depressive symptomatology among adult daughter caregivers of a parent with cancerCancer1998838165216639781961

- Gaston-JohanssonFLachicaEMFall-DicksonJMKennedyMJPsychological distress, fatigue, burden of care, and quality of life in primary caregivers of patients with breast cancer undergoing autologous bone marrow transplantationOncol Nurs Forum20043161161116915547639

- GauglerJELinderJGivenCWKatariaRTuckerGRegineWFThe proliferation of primary cancer caregiving stress to secondary stressCancer Nurs200831211612318490887

- HanrattyBHollandPJacobyAWhiteheadMFinancial stress and strain associated with terminal cancer–a review of the evidencePalliat Med200721759560717942498

- BrazilKBainbridgeDRodriguezCThe stress process in palliative cancer care: a qualitative study on informal caregiving and its implication for the delivery of careAm J Hosp Palliat Care201027211111620008823

- BurtonLCNewsomJTSchulzRHirschCHGermanPSPreventive health behaviors among spousal caregiversPrev Med19972621621699085384

- GivenCWGivenBStommelMCollinsCKingSFranklinSThe caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairmentsRes Nurs Health19921542712831386680

- GivenBWyattGGivenCBurden and depression among caregivers of patients with cancer at the end of lifeOncol Nurs Forum20043161105111715547633

- CarterPAFamily caregivers’ sleep loss and depression over timeCancer Nurs200326425325912886115

- ChoMHDoddMJLeeKAPadillaGSlaughterRSelf-reported sleep quality in family caregivers of gastric cancer patients who are receiving chemotherapy in KoreaJ Cancer Educ200621Suppl 1S37S4117020500

- HearsonBMcClementSSleep disturbance in family caregivers of patients with advanced cancerInt J Palliat Nurs2007131049550118073709

- TeelCSPressANFatigue among elders in caregiving and noncaregiving rolesWest J Nurs Res199921449851411512167

- LeeSColditzGABerkmanLFKawachiICaregiving and risk of coronary heart disease in U.S. women: a prospective studyAm J Prev Med200324211311912568816

- von KänelRMausbachBTPattersonTLIncreased Framingham coronary heart disease risk score in dementia caregivers relative to non-caregiving controlsGerontology200854313113718204247

- Kiecolt-GlaserJKFisherLDOgrockiPStoutJCSpeicherCEGlaserRMarital quality, marital disruption, and immune functionPsychosom Med198749113343029796

- RohlederNMarinTJMaRMillerGEBiologic cost of caring for a cancer patient: dysregulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory signaling pathwaysJ Clin Oncol200927182909291519433690

- SchulzRBeachSRCaregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects StudyJAMA1999282232215221910605972

- ChristakisNAAllisonPDMortality after the hospitalization of a spouseN Engl J Med2006354771973016481639

- Riess-SherwoodPGivenBAGivenCWWho cares for the caregiver: strategies to provide supportHome Health Care Manag Pract2002142110121

- SherwoodPRGivenBADonovanHGuiding research in family care: a new approach to oncology caregivingPsychooncology2008171098699618203244

- PearlinLIMullanJTSempleSJSkaffMMCaregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measuresGerontologist19903055835942276631

- BrownRMBrownSLInformal caregiving: a reappraisal of effects on caregiversSoc Issues Policy Rev20148174102

- LloydJPattersonTMuersJThe positive aspects of caregiving in dementia: a critical review of the qualitative literatureDementia20161561534156125547208

- ChengSTMakEPLauRWNgNSLamLCVoices of Alzheimer caregivers on positive aspects of caregivingGerontologist201556345146025614608

- LiQLokeAYA systematic review of spousal couple-based intervention studies for couples coping with cancer: direction for the development of interventionsPsychooncology201423773173924723336

- StenbergUEkstedtMOlssonMRulandCMLiving close to a person with cancer: a review of the international literature and implications for social work practiceJ Gerontol Soc Work2014576–753155524611782

- JansenASNguyenXVKarpitskiyVMettenleiterTCLoewyADCentral command neurons of the sympathetic nervous system: basis of the fight-or-flight responseScience199527052366446467570024

- WeitznerMAHaleyWEChenHThe family caregiver of the older cancer patientHematol Oncol Clin North Am200014126928110680082

- LuciniDCannoneVMalacarneMEvidence of autonomic dysregulation in otherwise healthy cancer caregivers: a possible link with health hazardEur J Cancer200844162437244318804998

- TeixeiraRJPereiraMGPsychological morbidity and autonomic reactivity to emotional stimulus in parental cancer: a study with adult children caregiversEur J Cancer Care2014231129139

- DeRijkRHSchaafMde KloetERGlucocorticoid receptor variants: clinical implicationsJ Steroid Biochem Mol Biol200281210312212137800

- PadgettDAGlaserRHow stress influences the immune responseTrends Immunol200324844444812909458

- RepettiRLTaylorSESeemanTERisky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspringPsychol Bull2002128233036611931522

- Kiecolt-GlaserJKGlaserRGravensteinSMalarkeyWBSheridanJChronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adultsProc Natl Acad Sci USA1996937304330478610165

- SchulzRNewsomJMittelmarkMBurtonLHirschCJacksonSHealth effects of caregiving: the caregiver health effects study: an ancillary study of the Cardiovascular Health StudyAnn Behav Med19971921101169603685

- LueckenLJLemeryKSEarly caregiving and physiological stress responsesClin Psychol Rev200424217119115081515

- DaviesPTCummingsEMMarital conflict and child adjustment: an emotional security hypothesisPsychol Bull199411633874117809306

- TaylorSERepettiRLSeemanTHealth psychology: what is an unhealthy environment and how does it get under the skin?Annu Rev Psychol1997484114479046565

- McCubbinHINeedleRHWilsonMAdolescent health risk behaviors: family stress and adolescent coping as critical factorsFam Relat1985345162

- BucherJZaboraJBuilding problem-solving skills through COPE education of family caregiversHollandJCBreitbartWSJacobsenPBLederbergMSLoscalzoMJMcCorkleRPsychooncology2nd edLondon, UKOxford University Press2010469472

- PatrickJHHaydenJMNeuroticism, coping strategies, and negative well-being among caregiversPsychol Aging199914227328310403714

- ElliottTRShewchukRMSocial problem-solving abilities and distress among family members assuming a caregiving roleBr J Health Psychol20038Pt 214916312804330

- FuemmelerBMullinsLLVan PeltJCCarpentierMYParkhurstJPosttraumatic stress symptoms and distress among parents of children with cancerChildren’s Health Care2005344289303

- Hoekstra-WeebersJJaspersJKlipECKampsWAFactors contributing to the psychological adjustment of parents of paediatric cancer patientsBaiderLCooperCLDe-NourAKCancer and the FamilyEnglandJohn Wiley & Sons2000257272

- SchumacherKLDoddMJPaulSMThe stress process in family caregivers of persons receiving chemotherapyRes Nurs Health19931663954048248566

- SalesESchulzRBiegelDPredictors of strain in families of cancer patients: a review of the literatureJ Psychosoc Oncol1992102126

- LewisFMThe impact of breast cancer on the family: lessons learned from the children and adolescentsBaiderLCooperCLDe-NourAKCancer and the FamilyChichesterJohn Wiley & Sons1996271287

- BrownMAStetzKThe labor of caregiving: a theoretical model of caregiving during potentially fatal illnessQual Health Res19999218219710558362

- LazarusRSFolkmanSPsychological Stress and the Coping ProcessNew YorkSpringer1984

- MaesSLeventhalHDe RidderDTDCoping with chronic dieseasesZienderMEndlerNSHandbook of Coping: Theory, Research, ApplicationsNew YorkJohn Wiley & Sons, Inc1996221245

- SchumacherKLBeidlerSMBeeberASGambinoPA transactional model of cancer family caregiving skillANS Adv Nurs Sci200629327128617139208

- GauglerJELinderJGivenCWKatariaRTuckerGRegineWFFamily cancer caregiving and negative outcomes: the direct and mediational effects of psychosocial resourcesJ Fam Nurs200915441744419776210

- ChenEMatthewsKACognitive appraisal biases: an approach to understanding the relation between socioeconomic status and cardiovascular reactivity in childrenAnn Behav Med200123210111111394551

- FloryJDMatthewsKAOwensJFA social information processing approach to dispositional hostility: relationships with negative mood and blood pressure elevations at workJ Soc Clin Psychol1998174491504

- FolkmanSPersonal control and stress and coping processes: a theoretical analysisJ Pers Soc Psychol19844648398526737195

- ApplebaumJABreitbartWCare for the cancer caregiver: a systematic reviewPalliat Support Care201311323125223046977

- WaldronEAJankeEABechtelCFRamirezMCohenAA systematic review of psychosocial interventions to improve cancer caregiver quality of lifePsychooncology20132261200120722729992

- NorthouseLLWilliamsALGivenBMcCorkleRPsychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancerJ Clin Oncol201230111227123422412124

- NorthouseLLKatapodiMCSchafenackerAMWeissDThe impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family caregivers and cancer patientsSemin Oncol Nurs201228423624523107181

- MenninDSFrescoDMEmotion regulation therapyGrossJJHandbook of Emotion Regulation2nd edNew York, NYGuilford Press2013469490

- ApplebaumAJBudaKLO’TooleMSHoytMAMenninDSAdaptation of Emotion Regulation Therapy for Cancer Caregivers (ERT-C)Poster presented at: 14th Annual Conference of the American Psychosocial Oncology SocietyFebruary 15–18, 2017Orlando, FL, USA

- ApplebaumAEmotion Regulation Therapy to address distress among cancer caregiversInvited presentation for the T.J. Martell Annual Scientific Meeting 2018Nashville, TN, USA

- ApplebaumASonTBevansMHernandezMDuHamelKThe unique experience of caregivers of outpatient hematopoetic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients: lessons learned from the inpatient HSCT LiteraturePoster presented at: 11th Annual Conference of the American Psychosocial Oncology SocietyFebruary 13–15, 2014Tampa, FL, USA

- Dellmann-JenkinsMBlankemeyerMEmerging and young adulthood and caregivingShifrenKHow Caregiving Affects Development: Psychological Implications/Or Child, Adolescent, and Adult CaregiversWashington, DC, USAAmerican Psychological Association200993118

- BrodyEMWomen in the Middle: Their Parent-Care YearsNew YorkSpringer2004