Abstract

Delusional infestation (DI), a debilitating psychocutaneous condition, featured as a false fixed belief of being infested accompanied by somatosensory abnormality, behavior alteration, and cognitive impairment. Although management of primary causes and pharmacotherapy with antipsychotics and/or antidepressants can help to alleviate symptoms in most patients, the underlying etiology of DI still remains unclear. Morgellons disease (MD), characterized by the presence of cutaneous filaments projected from or embedded in skin, is also a polemic issue because of its relationship with spirochetal infection. This review aims to discuss the following topics that currently confuse our understandings of DI: 1) the relationship of real/sham “infestation” with DI/MD; 2) behavior alterations, such as self-inflicted trauma; 3) neuroimaging abnormality and disturbance in neurotransmitter systems; and 4) impaired insight in patients with this disease. In discussion, we try to propose a multifactorial approach to the final diagnosis of DI/MD. Future studies exploring the neurobiological etiology of DI/MD are warranted.

Introduction

Delusional infestation (DI) is an uncommon, intricate psychocutaneous condition.Citation1 Against available medical evidence, patients with DI have a strong conviction that they are infested with little animals or less frequently inanimate matter.Citation1,Citation2 Meanwhile, patients always complain of abnormal skin sensations, such as stinging, biting, and crawling, which were ascribed to the “infestation”. The symptoms of DI can occur as primary, or more commonly, secondary to diverse medical conditions, such as neuropsychiatric diseases, nutrient deficiency, psychotropic medications, infections, intoxication, tumors, and metabolic disturbance.Citation3 Etiology-dependent management and antipsychotics/antidepressants have been reported to be therapeutically effective.Citation1,Citation3,Citation4

Worldwide retrospective researches and case reports have painted an inexplicit epidemiological picture of DI.Citation5–Citation7 In clinical practice, DI might be underdiagnosed as patients are always reluctant to psychiatric referral and prefer to visit dermatologists, microbiologists, and general practitioners. The prevalence of appropriately 80 cases per million was reported in private practices, while much less cases were presented and identified in public health services (appropriately 5.5 cases per million).Citation8 Middle-aged to elderly women, especially those with inadequate social contact, are more likely to be afflicted.Citation5–Citation8 The duration of illness can be less than 1 year or as long as three decades.Citation3 However, the final diagnosis and proper management of DI are always delayed.

To date, there are still many puzzles hindering our in-depth understanding of somatosensory abnormality, behavior alteration, and cognitive impairment in DI. 1) Are symptoms associated with DI simply delusional? Can real infestation cause DI-like symptoms? 2) How to unscramble the behavior pattern in DI patients, such as self-inflicted skin trauma? 3) Antipsychotics and/or antidepressants are generally effective in managing symptoms of DI. This phenomenon indicates disturbance in neurotransmitter systems according to the pharmacological actions of agents. Moreover, recent advances in neuroimaging researches of DI patients need to be updated, including brain anatomical and functional abnormalities. 4) Patients with DI commonly lost their insight of disease nature. Whether their insight can be restored after improvement in symptoms? A better characterizing of aforementioned puzzles is of significant importance in clinical practice and fundamental research.

Herein, we start with expounding the current knowledge of above puzzles. In the “Discussion” section, we try to propose a multifactorial approach, which helps to facilitate the diagnosis of DI/Morgellons disease (MD).

Sham or real infestation

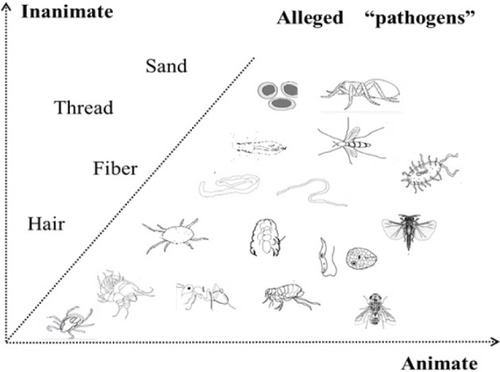

This question should be prudently answered, as it directly determines the nature of DI. To date, a great many of animate pathogens have been blamed, including all kinds of arthropods, worms, bacteria, and fungi.Citation8 These pathogens are always described as small and vivid. In contrast, inanimate matter, long and thin, such as fibers, threads, hair, and the like, is less frequently reported.Citation9 A comprehensive review of different “pathogens” is listed in .Citation10–Citation23 The specific type of alleged pathogen by certain patient could be affected by one’s own knowledge, life experience, and living environment. These pathogens might be wrapped with containers, referred to as the “specimen” or “matchbox” sign,Citation3 and taken to clinic or hospital as an evidence of infestation. For most of the time, however, microscopy or even skin biopsy fails to find out the alleged pathogenic agent. In addition, the abnormal skin sensations, such as stinging, crawling, biting, and pinching, intensify patients’ belief of infestation. In DI patients, abnormal activation of an itch pathway from the skin to the central nervous system is suspected.Citation16 Dysfunction of interoception, improper processing, and misinterpretation of perceived sensations contribute to the formation of tactile or even visual hallucinations. Of note, it seems that delusions are always infestation oriented and, apart from infestation, the individuals’ function well in other life scenes.

Figure 1 An atlas of alleged pathogens in patients with delusional infestation.

The closest diagnosis to DI in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the fifth edition (DSM-5), is somatic-type delusional disorder.Citation24 However, the diagnosis of delusional disorder should be exclusive, that is, the disturbance cannot be better explained by any substance, underlying mental comorbidities and psychical conditions.Citation24 Within this framework, most DI cases reported in literatures are secondary, not primary, and therefore could not be diagnosed as somatic-type delusional disorder. Whatever, we should first determine whether the belief is delusional or not.

MD, characterized as embedded or protruding filaments in skin lesions, was once considered as a variation of DI by some researchers.Citation3,Citation9 However, other researchers have claimed an infectious process underlying this disease. The presentation of specimen, which is further confirmed as cutaneous filaments, may not be delusional in some cases. They reported positive tests of Borrelia spirochetes in patients with MD.Citation22,Citation23 In these studies, the researchers found that patients with MD shared similar systematic symptoms (eg, skin irritation, fatigue, joint pain, cardiac complications, and cognitive deficits) to those with tick-borne illnesses, for example, Lyme disease.Citation25 They reported that the major components of MD cutaneous filaments were keratin and collagen, which were produced by keratinocytes and fibroblasts.Citation25 The formation of these filaments could be resulted from skin proliferation in underlying infectious process. Treatment of MD patients seems to be more challenging than those with DI patients.Citation26,Citation27 Therefore, MD seems more likely to be a discrete entity, rather than a variation of DI. Some studies against the infectious cause of MD have also been published. In the Pearson study, for instance, researchers did not found any link between MD and Lyme disease.Citation28 The histopathologic abnormality of skin samples was most likely to be solar elastosis, and most of the materials presented by the patients were composed of cellulose, compatible with cotton fibers.Citation28 However, the Pearson study selected patients via a retrospective review of medical records. The inclusion criteria in this study did not strictly require the presentation of embedded or protruding skin fibers. The patients were a heterogeneous group, and the fiber analysis was conducted in a small number of patients.Citation25,Citation28

Notably, neither MD nor DI is listed in DSM-5. Tests for Lyme disease are insensitive, which complicate the diagnosis. The use of techniques, such as immunostaining and PCR, to directly detect spirochetal pathogens in skin is needed. Moreover, the skin lesions caused by self-mutilation behaviors may result in secondary infection, which further complicates this condition. Based on current findings, MD is not a subtype of DI and its interplay with spirochetal infection needs further investigations.

Alterations in behavioral characteristics

Health-related quality of life was significantly reduced in DI patients. Individuals without this condition can hardly imagine the encounters of afflicted patients. These patients always isolate themselves and present altered behavioral characteristics, which can be typically classified into two patterns, outward and inward. A common explanation for these behaviors is to find out and eradicate the putative pathogens. Another reason could be a way to release anxiety and stress. However, negative medical findings and vain self-inflicted attempts, eventually result in a vicious circle, which promotes the persistence of disease and increases the severity of symptoms.

The outward pattern

1) Patients repetitively seek help from many doctors of different specialties and are prescribed with antibiotic, virucide, pesticide, or other anti-infectives.Citation15,Citation29 The effect of these medications is always unsatisfactory and sometimes detrimental, causing skin irritation and abnormal sensations similar to skin complaints of DI, as well as nausea, headache, diarrhea, fatigue, and even elevated liver enzymes.Citation15 2) In cases of DI by proxy, especially patients with children living together, precautionary protection of children from excessive cleansing is particularly important.Citation30 Similar condition is that pet owners hold a fixed, but false belief that their pets have been infested and need veterinary treatments.Citation31,Citation32 3) A increased risk of drug abuse was observed in DI patients, which would worsen their conditions.Citation5 However, the causes for this phenomenon is unclear and may relate to physical or psychiatric comorbidities. In the outward pattern, patients focus on the surroundings rather than their own body.

The inward pattern

1) Self-inflicted skin trauma caused by mechanical force or fingernails is thought to target the causative pathogen and relieve skin discomfort.Citation12,Citation33 2) Self-therapy with different chemicals or physical strategies aims to kill or flush away the pathogens from the body.Citation3,Citation34 3) Repetitive and intensive self-cleaning with an obsessive trait, such as frequent changing of clothes and hair washing, reflects excessive fear of contamination.Citation35 4) In addition, comorbidity with psychiatric diseases or depression, secondary to DI, is associated with increased proneness to suicidal ideations and attempts.Citation36 These inward behaviors are exhaustive, frustrated, and even detrimental and are generally more convenient to be implemented than outward behaviors.

The abnormal behaviors in DI patients are associated with their loss of disease insight. The skin lesions secondary to self-mutilation, eg, ulcerations, erosions, and pigmentations, can worsen the condition and sometimes were perceived as evidence of infestation.Citation3,Citation35 Apparently, these patients have difficulties in decision making and risk evaluation of their behaviors.Citation37 In general, abnormal behavioral patterns, accompanied with personality alteration, are adaptive to the anxiety and fear caused by uncomfortable skin sensations and hallucinations. Alterations in behaviors, in turn, may also consolidate the skin discomfort.

Updates on the neural correlates of DI

To date, the neural mechanisms of DI remain largely unknown. Many DI cases are secondary to various medical conditions, which make the issue more complicated. The role of genetic vulnerability and neurodevelopmental or neuroimmune aberration has been inadequately investigated. However, disturbance in brain neurotransmitter systems is evident since many cases of DI respond well to antipsychotic or antidepressant treatment. Recent neuroimaging findings of DI also need to be updated.

Imbalance in neurotransmitter systems

A comprehensive review of drugs that can elicit or otherwise treat DI is presented in .Citation13,Citation38–Citation60 Accordingly, several lines of dysfunction in neurotransmitter systems are revealed. Except for the well-known hyperactivity in dopamine system, dysfunction in serotonergic neurotransmission and adrenergic neurotransmission, as well as the histamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid circuits, should also be noted. These findings indicate a complicated biological underpinning of DI. First, different neurotransmitter pathways are involved and provide possible explanations for the diverse symptom spectrums of DI, eg, tactile hallucination, delusion, behavior, affect, and cognitive alterations. Second, these neurotransmitter pathways are interconnected and their interactions may contribute to the onset of DI. Third, not only neurotransmitter receptors but also their transporters and various enzymes appear to be neuropharmacological targets of drugs listed in . Therefore, the pharmacotherapy for DI patients should be established on the symptomatic features, past treatment responses, and adverse effects of medications.

Table 1 Drugs potential to elicit or treat DI

Advances in neuroimaging studies

Early studies have demonstrated cortical and subcortical atrophy in DI patients, including thalamus, striatum/putamen, and fronto-temporo-parietal network.Citation3,Citation61 Using surface-based analysis, DI patients were reported to have increased cortical thickness in the right medial orbitofrontal cortex, reduced surface area in the left inferior temporal gyrus, the pars orbitalis of the right frontal gyrus, the lingual gyrus, and the precuneus, and lower local gyrification index in the left postcentral, bilateral precentral, right middle temporal, inferior parietal, and superior parietal gyri.Citation62 These brain areas are associated with sensory perception, visuospatial control, and self-awareness. A recent multimodal study has confirmed the fronto-temporo-parietal network in mediating the core DI symptoms and revealed the possible functional pathway of antipsychotics on DI by blocking striatum D2 receptors.Citation63 Regardless of their etiology, different cases of DI seem to share similar pattern of gray matter volume change in brain regions, such as frontal, temporal, parietal, insular lobes, thalamus, and striatum.Citation64 With a combination of functional MRI and an infestation-relevant visual task, a more recent study has highlighted fronto-limbic dysfunction within insula, amygdala, and prefrontal lobe, which is associated with differences in self-representation.Citation65 The findings were overlapped in these studies, and neuroimaging abnormalities in brain regions, such as thalamus, striatum/putamen, and insula, have been repetitively documented.Citation66 The dysfunction in sensorimotor and peripersonal networks may possibly explain the somatic delusions in DI patients.Citation66

However, the alterations in certain brain regions may result from infections, such as spirochetal infection, either via direct cerebral invasion or via immune pathways in susceptible individuals. Moreover, it is still unknown that the neurological changes in DI patients are reversible or persistent after symptom remission.

Insight

Insight of disease nature is an important indicator of disease severity. Self-destructive behaviors in DI patients are considered to correlate with a loss of disease insight. Indeed, many patients are reluctant to psychiatric referrals and antipsychotics/antidepressants. It is the satisfactory efficacy of psychotropic agents that make them to believe it might be the right way to solve their problems. However, little attention has been paid to the restoration of insight after symptom remission.

According to an observational study, symptom recurrence is common in DI patients when treatment is discontinued.Citation67 This phenomenon reflects that at least a subgroup of DI population is intractable and their temporal response to pharmacotherapy does not equal to full restoration of disease insight. In fact, despite the salient treatment efficacy, some patients may spontaneously stop taking psychotropic agents. It has been reported that the side effects of these drugs are the main reason for their nonadherence to medications.Citation68 However, similar to other studies, this study also neglected the role of impaired insight on this issue.

Herein, we believe that the insight deficits in DI patients merit more attention. Partial or complete lack of insight will delay the diagnosis and impair treatment outcome, adherence to medications, and long-term functioning improvement. Physicians should focus not only on the remission in clinical symptoms but also on the patients’ understanding of their sufferings and medications. Therefore, long-term follow-up is of great importance for DI patients after symptom remission.

Discussion

In this article, we put forward some unresolved puzzles and debates of DI/MD and discuss them based on the recent findings. The etiology of DI is possibly multifactorial as many DI cases are secondary to various medical conditions. The closest diagnosis to DI in DSM-5 is somatic-type delusional disorder. However, only the primary type of DI met the diagnostic criteria of this delusional disorder. MD is a similar condition to DI, but its relationship with tick-borne illnesses has been supported by a series of studies. DI patients have characteristic alterations in behavior pattern that could result from abnormal skin sensations, emotional anxiety, and stress. The disrupted behaviors are enhanced in a vicious circle because of failure to eliminate the alleged pathogens. Herein, for the first time, we put forward the concepts of inward and outward patterns of behaviors. Different case reports have demonstrated that a series of psychotropic agents are effective for treating DI. However, no well-designed clinical studies have ever verified the efficacy of these agents. The disturbance of various neurotransmitter systems again indicates the complexity of DI. Neuroimaging findings are in part consistent among different studies with different designs. The abnormal brain areas are involved in neural circuits associated with self-awareness, self-representation, visuospatial control, and sensory perception. The relationship between neurological changes and spirochetal infection needs more investigation. Patients with DI have deficits in disease insight, and their insight may fail to be fully restored after remission in symptoms. The insight in DI patients calls for more attention because it affects the timely diagnosis, treatment adherence, and long-term outcome.

The onset of DI depends on various factors, including genetic susceptibility, personality traits, life experience, and primary medical conditions. The intensification and maintenance of DI symptoms are influenced by unquenched environment stimuli, brain structural and functional alterations, and untreated primary diseases. The diagnosis and treatment of DI patients should be individualized and evidence based. As for a specific patient, the diagnosis of primary DI could be made only after ruling out other possible causes. However, the definition or inclusion criteria for DI/MD vary among previous studies. To facilitate the diagnosis of DI/MD in clinical practice, we herein try to propose a multifactorial approach as follows.

The first step needs to determine whether delusion exists or not. A delusion is defined as a firmly, but false belief held with strong conviction and contrary to the superior evidence. It is distinct from beliefs based on an unusual perception, such as formication. The beliefs that patients hold could be delusion, true observations, or overvalued ideas. This must be determined on a case-by-case basis. The presentation of a specimen is not a delusional behavior. Patients with DI/MD with animate or inanimate objects can exist, but the belief of cutaneous fibers may or may not be delusional. A physician is required to perform fiber analysis to identify the nature of fibers. If fibers are present and biofilaments of human origin, then they are a true observation. It is also possible that patients might observe fibers and mistake them for worms in which case the idea of infestation could be an overvalued idea. Real infestation with arthropods such as mites can also occur. Additionally, some patients could have lesions with adhering textile fibers that are accidental contaminants and could mistakenly believe that they have MD, in which case they do not have a delusional belief, but a mistaken belief. In summary, if a physician cannot differentiate between true observations, delusions, and overvalued ideas, they should not immediately make a diagnosis of delusional mental illness.

The next procedure would be screening the causes of the symptoms. If a delusional belief is present, then various medical conditions need to be ruled out, including psychiatric disorders (eg, schizophrenia and depression), neurological illnesses (eg, dementia), metabolic illnesses (eg, diabetes), vitamin deficiencies, substance intoxication, tumor, dermatological illnesses (eg, pruritus senilis), and infection. History taking, physical examination, laboratory tests, and even skin biopsy should be carried out. The diagnosis of DI could be classified as primary and secondary. If there are cutaneous fibers present and the belief is not delusional, the underlying cause of the symptoms, such as potential infection, should be examined. A diagnosis of MD is more convincing when spirochetal infection is identified. If a patient has delusional beliefs and has cutaneous fibers, then testing of an underlying infection that can result in neuropathy is needed.

Conclusion

The relationship between DI/MD and infestation, the abnormal behavior pattern, the disrupted brain function and structure, and disease insight have been discussed in this article. Clinical diagnosis of DI/MD should be stepwise, and interdisciplinary examinations of underlying causes are needed. Future studies on DI/MD, especially the neurobiological mechanisms, are warranted.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants of the National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFC1307100 and 2016YFC1307102), the Public Welfare Project of Science Technology Department of Zhejiang Province (2015C33133), the National Science and Technology Program (2015BAI13B02), and the Key Research Project of Zhejiang Province (2015C03040).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KooJLeeCSDelusions of parasitosis. A dermatologist’s guide to diagnosis and treatmentAm J Clin Dermatol20012528529011721647

- BewleyAPLeppingPFreudenmannRWFreundenmannRWTaylorRDelusional parasitosis: time to call it delusional infestationBr J Dermatol2010163112

- FreudenmannRWLeppingPDelusional infestationClin Microbiol Rev200922469073219822895

- HellerMMWongJWLeeESDelusional infestations: clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatmentInt J Dermatol201352777578323789596

- FosterAAHylwaSABuryJEDelusional infestation: clinical presentation in 147 patients seen at Mayo ClinicJ Am Acad Dermatol2012674673.e11022264448

- FreudenmannRWLeppingPHuberMDelusional infestation and the specimen sign: a European multicentre study in 148 consecutive casesBr J Dermatol2012167224725122583072

- BaileyCHAndersenLKLoweGCA population-based study of the incidence of delusional infestation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976-2010Br J Dermatol201417051130113524472115

- TrabertWDelusional parasitosis. Studies on frequency, classification and prognosis [Dissertation]Universita¨t des SaarlandesHomburg/Saar, Germany1993

- HarthWHermesBFreudenmannRWMorgellons in dermatologyJ Dtsch Dermatol Ges20108423424219878403

- LewisASOldhamMADelusional Infestation With Black Mold Presenting to the General HospitalPrim Care Companion CNS Disord2015172

- SawantNSVisputeCDDelusional parasitosis with folie à deux: A case seriesInd Psychiatry J2015241979826257494

- BeachSRKroshinskyDKontosNCase records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 37-2014. A 35-year-old woman with suspected mite infestationN Engl J Med2014371222115212325427115

- StanciuCNPendersTMOxentineHNDelusional infestation following misuse of prescription stimulantsPsychosomatics201556221021225262039

- Battistelli-LuxCBuccal infection with Gongylonema pulchrum: an indigenous case in FranceAnn Dermatol Venereol20131401062362724090893

- TranMMIredellJRPackhamDRO’SullivanMVHudsonBJDelusional infestation: an Australian multicentre study of 23 consecutive casesIntern Med J201545445445625827513

- KimseyLSDelusional Infestation and Chronic Pruritus: A ReviewActa Derm Venereol201696329830226337109

- HopkinsonGDelusions of infestationActa Psychiatr Scand19704621111195478538

- WilhelmiJUngezieferwahnMed Welt19359351354

- SchwarzDrH. Zirkumskripte HypochondrienEur Neurol1929722-3150164

- FreudenmannRWA case of delusional parasitosis in severe heart failure. Olanzapine within the framework of a multimodal therapyNervenarzt200374759159512861369

- HarbauerHDas Syndrom des “Dermatozoenwahns” (Ekbom)Nervenarzt194920254258

- MiddelveenMJBuruguDPoruriAAssociation of spirochetal infection with Morgellons diseaseF1000Res201322524715950

- MiddelveenMJBandoskiCBurkeJExploring the association between Morgellons disease and Lyme disease: identification of Borrelia burgdorferi in Morgellons disease patientsBMC Dermatol201515125879673

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders5th edSt LouisAPA2016

- MiddelveenMJFeslerMCStrickerRBHistory of Morgellons disease: from delusion to definitionClin Cosmet Investig Dermatol2018117190

- DewanPMillerJMustersCTaylorREBewleyAPDelusional infestation with unusual pathogens: a report of three casesClin Exp Dermatol201136774574821933231

- SandhuRKSteeleEAMorgellons Disease Presenting As an Eyelid LesionOphthal Plast Reconstr Surg2014 Epub ahead of print

- PearsonMLSelbyJVKatzKAClinical, epidemiologic, histopathologic and molecular features of an unexplained dermopathyPLoS One201271e2990822295070

- FreudenmannRWDelusions of parasitosis: an up-to-date reviewFortschr Neurol Psychiatr20027010531541 German [with English abstract]12376915

- AhmedHBlakewayEATaylorREBewleyAPChildren with a mother with delusional infestation--implications for child protection and managementPediatr Dermatol201532339740025641024

- LeppingPRishniwMFreudenmannRWFrequency of delusional infestation by proxy and double delusional infestation in veterinary practice: observational studyBr J Psychiatry2015206216016325497298

- RishniwMLeppingPFreudenmannRWDelusional infestation by proxy--what should veterinarians do?Can Vet J201455988789125183897

- BhatiaMSJhanjeeASrivastavaSDelusional infestation: a clinical profileAsian J Psychiatr20136212412723466108

- AltunayIKAtesBMercanSDemirciGTKayaogluSVariable clinical presentations of secondary delusional infestation: an experience of six cases from a psychodermatology clinicInt J Psychiatry Med201244433535023885516

- HinkleNCEkbom syndrome: the challenge of “invisible bug” infestationsAnnu Rev Entomol201055779419961324

- MunroAMonosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosisBr J Psychiatry Suppl198823740

- GlimcherPWRustichiniANeuroeconomics: the consilience of brain and decisionScience2004306569544745215486291

- Gross-TsurVJosephAShalevRSHallucinations during methylphenidate therapyNeurology200463475375415326264

- KrauseneckTSoykaMDelusional parasitosis associated with pemolinePsychopathology200538210310415855835

- YehT-CLinY-CChenL-FAripiprazole treatment in a case of amphetamine-induced delusional infestationAust N Z J Psychiatry201448768168224563196

- SpensleyJRockwellDAPsychosis during methylphenidate abuseN Engl J Med1972286168808815061074

- RosenzweigIRamachandraPFreerJWongMPietersTDelusional parasitosis associated with donepezilJ Clin Psychopharmacol201131678178222051921

- KölleMLeppingPKassubekJSchönfeldt-LecuonaCFreudenmannRWDelusional infestation induced by piribedil add-on in Parkinson’s diseasePharmacopsychiatry201043624024220614418

- AizenbergDSchwartzBZemishlanyZDelusional parasitosis associated with phenelzineBr J Psychiatry19911597167171756352

- ReillyTMJoplingWHBeardAWSuccessful treatment with pimozide of delusional parasitosisBr J Dermatol1978984457459638052

- AndrewsEBellardJWalter-RyanWGMonosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis manifesting as delusions of infestation: case studies of treatment with haloperidolJ Clin Psychiatry19864741881903957878

- SrinivasanTNSureshTRJayaramVFernandezMPNature and treatment of delusional parasitosis: a different experience in IndiaInt J Dermatol199433128518557883408

- CupinaDBoultonMSecondary delusional parasitosis treated successfully with a combination of clozapine and citalopramPsychosomatics201253330130222560648

- KansalNKChawlaOSinghGPTreatment of delusional infestation with olanzapineIndian J Psychol Med201234329729823436955

- FreudenmannRWLeppingPSecond-generation antipsychotics in primary and secondary delusional parasitosis: outcome and efficacyJ Clin Psychopharmacol200828550050818794644

- BhatiaMSRathiAJhanjeeADelusional infestation responding to blonanserinJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci2013254E54

- PonsonLAnderssonFEl-HageWNeural correlates of delusional infestation responding to aripiprazole monotherapy: a case reportNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat20151125726125673993

- YehTCLinYCChenLFAripiprazole treatment in a case of amphetamine-induced delusional infestationAust N Z J Psychiatry201448768168224563196

- AltınözAETosunAltınöz ŞKüçükkarapınarMCoşarBPaliperidone: another treatment option for delusional parasitosisAustralas Psychiatry201422657657825147315

- FreudenmannRWKühnleinPLeppingPSchönfeldt-LecuonaCSecondary delusional parasitosis treated with paliperidoneClin Exp Dermatol200934337537719040517

- de BerardisDSerroniNMariniSSuccessful ziprasidone monotherapy in a case of delusional parasitosis: a one-year followupCase Rep Psychiatry2013201391324823762722

- HayashiHAkahaneTSuzukiHSuccessful treatment by paroxetine of delusional disorder, somatic type, accompanied by severe secondary depressionClin Neuropharmacol2010331484919935408

- DelacerdaAReichenbergJSMagidMSuccessful treatment of patients previously labeled as having “delusions of parasitosis” with antidepressant therapyJ Drugs Dermatol201211121506150723377524

- OtaniKMiuraYSuzukiAKinoshitaOEffectiveness and safety of milnacipran treatment for a patient with delusional disorder, somatic type taking multiple medications for concomitant physical diseasesClin Neuropharmacol201033421221320386103

- BoggildAKNicksBAYenLDelusional parasitosis: six-year experience with 23 consecutive cases at an academic medical centerInt J Infect Dis2010144e317e321

- HuberMKarnerMKirchlerELeppingPFreudenmannRWStriatal lesions in delusional parasitosis revealed by magnetic resonance imagingProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry20083281967197118930778

- HirjakDHuberMKirchlerECortical features of distinct developmental trajectories in patients with delusional infestationProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry201776727928257853

- FreudenmannRWKölleMHuweADelusional infestation: neural correlates and antipsychotic therapy investigated by multi-modal neuroimagingProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry20103471215122220600460

- WolfRchHuberMLeppingPSource-based morphometry reveals distinct patterns of aberrant brain volume in delusional infestationProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry20144811211624120443

- EcclesJAGarfinkelSNHarrisonNASensations of skin infestation linked to abnormal frontolimbic brain reactivity and differences in self-representationNeuropsychologia201577909626260311

- HuberMWolfRCLeppingPRegional gray matter volume and structural network strength in somatic vs. non-somatic delusional disordersProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry20188211512229180231

- WongSBewleyAPatients with delusional infestation (delusional parasitosis) often require prolonged treatment as recurrence of symptoms after cessation of treatment is common: an observational studyBr J Dermatol2011165489389621605110

- AhmedABewleyADelusional infestation and patient adherence to treatment: an observational studyBr J Dermatol2013169360761023600661