Abstract

Anxiety disorders are the most common mental health problems experienced by young people, and even mild anxiety can significantly limit social, emotional, and cognitive development into adulthood. It is, therefore, essential that anxiety is treated as early and effectively as possible. Young people are unlikely, however, to seek professional treatment for their problems, increasing their chance of serious long-term problems such as impaired peer relations and low self-esteem. The barriers young people face to accessing services are well documented, and self-help resources may provide an alternative option to respond to early manifestations of anxiety disorders. This article reviews the potential benefits of self-help treatments for anxiety and the evidence for their effectiveness. Despite using inclusive review criteria, only six relevant studies were found. The results of these studies show that there is some evidence for the use of self-help interventions for anxiety in young people, but like the research with adult populations, the overall quality of the studies is poor and there is need for further and more rigorous research.

Introduction

Young people have high rates of mental disorder, with the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) finding that 22.2% of young people aged 13–18 years in the United States suffer from a mental health problem that causes them severe distress.Citation1 The most common mental health problems are anxiety disorders, and the median age of onset is prior to adolescence. Consequently, the preadolescent and adolescent years are critical for implementing preventive and early interventions, yet young people are reluctant to seek professional mental health care. Self-help therapies may, therefore, be critical to effectively intervening to address young people’s anxiety without the need for professional service use. This paper reviews the development and current evidence base for such self-help therapies for use by young people with mild anxiety disorders.

Mild anxiety disorder

Anxiety disorders comprise a number of specific mental disorders including: generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder (SAD), panic disorder without agoraphobia, panic disorder with agoraphobia, specific/isolated phobia, separation anxiety disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety disorder due to a medical condition, and anxiety disorder not specified.Citation2 Anxiety disorders have been identified as being the most common mental health problem, with 18.1% of the adult population in the United States meeting the criteria as described in the DSM-IV.Citation3 The most common of the anxiety disorders are generalized anxiety disorder and SAD. Anxiety disorders are of particular concern for young people with the median age of onset for all anxiety disorders being 11 years of age. Estimates for the median age of onset for specific anxiety disorders, such as separation anxiety disorder, are as low as 7 years.Citation4

Each of the anxiety disorders can be classified as being severe, moderate, or mild and such classifications depend upon the criteria of the particular measure used. However, the main distinctions between mild disorders and those that are moderate or severe tend to be suicide risk and role impairment, which are used to distinguish clinically significant from clinically non-significant (mild) disorder.Citation5 For example, Kessler et alCitation3 describe the components for severe anxiety disorders as including: a 12-month suicide attempt with serious lethality intent; work disability or substantial limitation due to the anxiety disorder; or 30 or more days out of a role in a year due to the anxiety disorder. Anxiety disorders were “moderate” if they did not fit into the “severe” category and had: suicide gesture, plan or ideation; concurrent substance dependence without serious role impairment; moderate work limitation; or moderate role impairment.Citation6 Anxiety disorders which did not fit into either the “severe” or “moderate” category were described as mild.

Anxiety disorders are highly debilitating in childhood and adolescence and if left untreated can lead to other mental health problems, suicidal behavior, teenage parenthood, early marriage, and unemployment.Citation7–Citation11 Anxious children are less likely to complete schooling, with their teachers stating that they have problems with attention, deficits in academic performance, and are significantly more immature than their non-anxious peers.Citation12 Anxious children face social disadvantages as they are often less liked by their peers who find them socially withdrawn and shy.Citation12 The social pressure faced by young people with anxiety disorders can result in many turning to inefficient and harmful coping strategies such as overeating or harmful alcohol use.Citation13 Serious longterm effects that impact throughout adulthood can occur even for young people with relatively mild problems,Citation14 and it is imperative that effective preventive and early interventions are developed for young people with anxiety.

Treating anxiety

The accepted evidence-based approach in the treatment of anxiety disorders is cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which challenges and tries to change negative or irrational thinking and behavior patterns.Citation15,Citation16 CBT involves identifying components of the disorder and applying specific treatments to those components. For anxiety disorders, these components may include physiological arousal, muscle tension, cognitive worries, and avoidance behaviors.Citation17 Specific treatments include relaxation techniques, cognitive restructuring, targeting irrational fears through education, and graded exposure therapy.Citation17

Anxiety treatments for children generally comprise five components: psychoeducation, somatic management skills training, cognitive restructuring, exposure, and relapse prevention.Citation18 Psychoeducation involves teaching information about anxiety and feared stimuli. Somatic management skills training involves targeting automatic arousal responses. Cognitive restructuring focuses on changing maladaptive thoughts. Exposure comprises graduated, systematic, and controlled exposure to feared stimuli and situations. Relapse prevention consolidates learning and supports generalization of treatment to other situations.Citation18 Even relatively brief CBT, based on these components, effectively reduces anxiety symptoms and distress and improves psychosocial functioning in children and adolescents, and can be delivered in individual therapy or group sessions.Citation19,Citation20

Barriers to young people accessing service-based treatment

Despite high rates of mental disorder and the availability of effective treatments, most young people do not access mental health treatment services. Studies from many countries show that only 10%–30% of young people will seek professional help for their mental health problems.Citation21–Citation27 For example, a study conducted in Germany of young people aged 12–17 years who had anxiety, found that only 18.2% had sought help for their problem.Citation28 Within this study, young people with post-traumatic stress disorder were most likely to seek help (47.1%), and young people with a non-specific phobia were least likely to seek treatment (0.22%).

Several barriers have been consistently identified as reasons why young people fail to seek professional help.Citation29 One of these reasons is the strong belief held by young people that they should cope alone.Citation30 This is reflected in their high admiration of peers who do not require help from others for their personal problems.Citation31 Other factors include negative beliefs or attitudes about mental illnesses or the available treatments,Citation32,Citation33 being male,Citation34–Citation37 low mental health literacy,Citation38–Citation40 and inadequate social or interpersonal skills.Citation14,Citation41 Young people who have had negative past experiences with mental health professionals have also been shown to be less likely to seek treatment in the future.Citation42

The pathways to care for younger children are also complex. Children need to rely on their parents or caregivers to first identify that a problem exists and then seek out appropriate support.Citation43 Commonly reported reasons why parents do not seek help for their children are because of cost, not knowing where to seek help, and long waiting lists.Citation44 Other identified reasons include a lack of knowledge about the consequences of untreated child mental disorders, lack of knowledge of effective treatments, and difficulty in getting their child to regular appointments.Citation45

Self-help interventions

Self-help approaches avoid many of the barriers that affect access to traditional face-to-face treatment services, and provide an important alternative that can increase access to effective interventions. Self-help is likely to be particularly attractive for adolescents as it allows young people to seek help independently from their parents, supporting their natural developmental trend towards independence.Citation30,Citation46 The anonymity of self-help interventions is likely to be valued by young people who fear the stigma associated with service use and negative attitudes towards mental health care. Self-help approaches also allow for flexibility in time and place of delivery, and can be especially beneficial for those who cannot easily access face-to-face services.Citation47–Citation49

There are many variations of self-help, which means that as a category of interventions they are not easy to define. Self-help ranges from non-interactive information and psychoeducation to interactive intervention programs based on empirically supported treatments with individualized feedback.Citation50,Citation51 A comprehensive definition is provided by Bower, Richards, and Lovell who state that self-help is:

a therapeutic intervention administered through text, audio, video, or computer text, or through group meetings or individualized exercises such as “therapeutic writing,” and

designed to be conducted predominantly independently of professional contact.Citation52

Self-help interventions can be classified into one of three categories: general self-help; problem-focused self-help; and technique-focused self-help.Citation53 General self-help approaches are those that address broad-spectrum emotional and relational problems, and provide guidelines for general well-being.Citation53 These may also involve various social support interventions. Citation54 Problem-focused approaches are those that target a specific disorder, such as anxiety.Citation53 Technique-focused approaches teach users how to use a specific technique that may be useful in multiple situations, such as CBT or relaxation.Citation53 Problem and technique-focused approaches are generally informed by theory and have been empirically tested and specifically designed to create positive cognitive, behavioral, and emotional changes.Citation17,Citation50 Interventions that use problem-focused or technique-focused methods are usually delivered through modules with moderate to high interactivity, automated or human-generated feedback, and automated tailoring.Citation50

Self-help books for anxiety have been widely available for many years and are frequently amongst the top 100 best sellers.Citation55 These are available for both adults and children and some well-known titles include: Calming Your Anxious Mind: How Mindfulness and Compassion Can Free You From Anxiety, Fear and Panic;Citation56 Helping Your Anxious Child: A Step-by-step Guide for Parents;Citation57,Citation58 Freeing Your Child From Anxiety: Powerful, Practical Solutions to Overcome Your Child’s Fears, Worries, and Phobias;Citation59 and Anxiety in Childhood and Adolescence.Citation60 Although such books are popular, and they are often developed by experienced clinicians and based on strong conceptual frameworks, they are rarely supported by direct evidence of their effectiveness.Citation61

Over the past decade or so, self-help treatments have moved from being based mostly on self-help books and bibliotherapy to use of new technologies.Citation62 Self-help approaches have been quick to adopt new technologies, and recent interventions have been developed to use on internet sites, through email or chatrooms, on palmtops, with virtual reality technology, and on CD-ROM programs.Citation45 Some of these interventions are highly advanced and offer multiple sessions using specific therapeutic techniques, as well as containing non-specific features that affect important therapeutic processes, such as the therapeutic alliance, engagement, motivation, and trust.Citation63 Online self-help approaches have grown rapidly in recent years, responding to the increase in house-holds that have access to the internet and, in particular, the high level of uptake of new technologies by young people. Citation64 The majority of these interventions have undergone only initial trials to aid their development, however, and quality evidence of effectiveness is lagging.

Although self-help interventions are by definition devised to be undertaken without the support of a professional, in practice they are often implemented with varying degrees of professional support. They span the entire spectrum – from being entirely self-administered without even professional recommendation to being integrated within traditional face-to-face therapy as homework, a component of therapy or recommended self-management resources.Citation16,Citation55,Citation65 Self-help options are also often used to treat important comorbidities that are not the main focus of therapy, freeing valuable therapy session time to focus on the primary issue.

Current evidence

To date, the majority of research on self-help treatments for anxiety disorders has been undertaken with adult samples, and the results are mixed. A recent systematic review identified 13 studies meeting the inclusion criteria for a review of the clinical effectiveness of CBT-based guided self-help for anxiety and depressive disorders.Citation66 A subsequent meta-analysis indicated moderate effectiveness at post-treatment for anxiety, although limited effectiveness at follow-up was found among more clinically representative samples. Studies that reported greater effectiveness tended to be of lower methodological quality and generally involved participants who were self-selected rather than recruited through clinical referrals.

Other meta-analytic reviews also show that self-help interventions in the treatment of anxiety disorders for adults produce improvements with a medium effect size, but with poor-to-moderate quality evidence.Citation17,Citation47,Citation48,Citation52,Citation61,Citation65,Citation67–Citation73 Some trials have failed to show significant improvements in symptoms when compared to control groups,Citation74,Citation75 while others indicate significant improvements, comparable to that of traditional face-to-face therapy interventions.Citation76–Citation81 Most studies, however, have significant methodological limitations, such as small sample sizes, high attrition rates, no control group, and limited control over whether participants were also seeking additional psychological treatments or were taking medications.Citation52,Citation65 The best outcomes have been demonstrated in the treatment of panic disorder and specific phobias.Citation61,Citation70 Overall, as stated by Bower et al,Citation52 based on the Cochrane collaboration classification, self-help strategies for anxiety “appear promising but require further investigation.”

A review of self-help interventions for anxiety specifically for young people has not been undertaken. The current study aimed to redress this gap by conducting a systematic review of the literature on self-help interventions for anxiety disorders in young people to determine the state and nature of the current evidence base.

Methodology

A systematic review of the literature was undertaken by reviewing all studies that met the selection criteria for self- help interventions for anxiety for young people. Self- help interventions were defined as those that claimed to be self- help or self-administered, and did not involve a service or therapist-based therapy component or be based primarily on a parent-focused intervention. All anxiety disorders referred to as anxiety were included. Young people were defined as those aged 6–25 years. While the term “young people” usually denotes those aged 12–25 years,Citation82 interventions aimed at those in the preadolescent years were also included because anxiety disorders are highly likely to first emerge in young people aged 6–11 years.Citation4

Initially, a broad search strategy was implemented covering all studies published in English between January 1, 1970 and October 20, 2011 from the following EBSCO databases: Academic Search Complete, CINAHL Plus, Computers and Applied Sciences Complete, Education Research Complete, Health Source – Consumer Edition, Health Source – Nursing/Academic Edition, Humanities International Complete, MasterFILE Premier, MEDLINE, PsychArticles, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, Psych INFO, and Teacher Reference Center. The search terms used were: “anxiety” AND “self-help” OR “self help” OR “bibliotherapy” OR “self-administered” OR “therapist guided” OR “young people”; “anxiety” AND “children” AND “self-help”; “mental disorder” AND “self-help”; “self-help” AND “young people” OR “adolesc*”; “anxiety” AND “prevention” OR “early intervention.” Further studies were identified through hand searching the references of relevant studies and reviews.

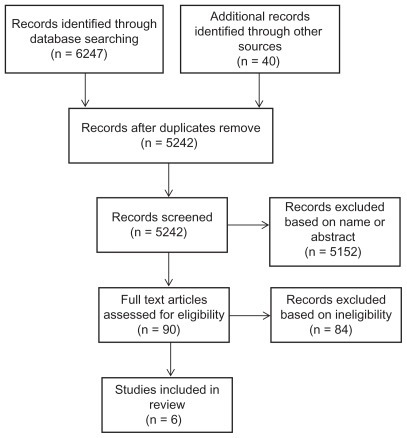

Following the database search, abstracts and titles were scanned independently by both authors and irrelevant studies were removed; the remaining full text articles were assessed for eligibility. The final eligibility criteria were that the study: examined a type of self-help intervention for an anxiety disorder; was published after 1995; involved participants aged between 6–25 years; had little or no parental involvement; was published in English; had more than one participant (ie, not single case studies); and comprised an outcome study with a focus on change in a measure of anxiety. Acceptable designs included randomized controlled trials (RCT), quasi-experimental trials, pre-post test case series, and longitudinal designs all able to be included. shows the Prisma flow diagram for study inclusion.

Results

A total of six studies met the inclusion criteria and a summary of each is provided in . These studies involved three interventions that are available to the general public – MoodGym,Citation83 CoolTeens CD-ROM,Citation15 the Online Anxiety Prevention Program,Citation84,Citation85 and three interventions that are not publicly available – an internet-based CBT program,Citation86 a computer-based Cognitive-Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP),Citation87 and a series of self-administered interventions for worry.Citation88 Four of the studies were RCTs,Citation83–Citation86,Citation88 comparing the intervention group(s) with a wait-list control (WLC) group and one was a small sample case series design.Citation15

Table 1 Study characteristics

Cognitive-behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy

Cukrowicz and JoinerCitation87 adapted CBASP into a computer-based program to determine whether it could be used as a self-help approach to reducing mild symptoms of anxiety and depression. CBASP asks participants to analyze specific incidents to determine and change patterns of maladaptive thinking and behaving. It involves five steps: description of the situation; interpretation of the situation; behaviors during the situation; actual outcome of the situation; and desired outcome of the situation. In the study, 231 young adults were randomly assigned to CBASP or an education program control group. The intervention comprised six, 20 minute sessions which were all completed in one 2-hour time frame undertaken in a computer laboratory at the university. Following the intervention, participants were sent weekly emails for 8 weeks reminding them to practice the skills they had learnt. The control group completed a program of similar length that focused on educational material around anxiety disorders. At the 8-week follow-up, participants in the intervention group had significantly lower scores on the measures of anxiety when compared to the control group. The effect size for the reduction in anxiety was moderate; on average, anxiety levels of participants in the intervention group reduced by half a standard deviation point following the intervention.

Although the sample size was large in this study, and there was a low attrition rate of 10%, it is difficult to generalize these completion rates to the wider population. The sample was predominately female, and obtained from an introductory psychology course where participants received course credit for completion. In addition, although the program was conducted independently, it was completed at a specified time with researchers and other participants present. This is likely to have greatly increased the completion rates and does not indicate how many young people are likely to independently complete this program at home.

Online anxiety prevention program

Studies by Kenardy et alCitation84,Citation85 investigated the Online Anxiety Prevention Program, which is a computer assisted CBT-based intervention comprising six sessions that incorporate psychoeducation about anxiety, relaxation training, interoceptive exposure, cognitive restructuring, and relapse prevention. Each session required participants to cover the program material, practice a set of skills, and record their progress daily. The study used 83 first year university students high on a measure of anxiety sensitivity who were randomly assigned to an intervention or WLC group. At 6-week follow-up, those in the intervention group showed improvements in some outcome measures, but not the Anxiety Sensitivity Index measure.Citation84 At 6 months, 53% of the intervention group and 61% of the control group were followed up.Citation85 Significant decreases in anxiety sensitivity were evident for both the control and intervention group participants. The study was significantly limited by its mostly adult and university population sample group, small sample size, and lack of significant findings.

MoodGYM

MoodGYM is a free internet-based CBT intervention developed by researchers at the Australian National University and designed to treat anxiety and depression.Citation89 The program was originally developed for adults, is accessible 24 hours a day and is self-paced. It consists of five CBT modules that take approximately 30–45 minutes each to complete, a personal workbook that records and updates user’s responses, an interactive game, and a feedback evaluation form.

The study by Sethi et alCitation83 was an RCT using 38 first year undergraduate psychology students (aged 18–23 years) randomized into four conditions: MoodGYM as a pure self-help intervention; MoodGYM in conjunction with face-to-face therapy; a traditional face-to-face therapy group; and a control group. At 5-week post-test, there was no change in anxiety for participants in the control group, and those in the MoodGYM only condition had significantly decreased anxiety scores with a medium effect size compared with the control group. A similar decrease was evident for those in the traditional face-to-face therapy group. However, the greatest reduction in anxiety was achieved in the combined condition where MoodGYM was provided in conjunction with face-to-face therapy. The study authors suggest that meeting with a therapist first and then using MoodGYM motivates the user to do well on the self-help program and allows for skills to be practiced, leading to superior outcomes.

There were considerable limitations to this study, however. Foremost, the sample was made up of university students undertaking the study for credit points. Participants undertook the self-help component in group sessions at the university. Furthermore, no follow-up data were obtained to determine whether treatment gains were maintained.

Internet CBT

Tillfors et alCitation86 examined the effectiveness of an internet-based CBT program for social anxiety that was developed for use with adult university students and adapted for use with high school students. There were nine weekly modules that each consisted of information, exercises, and essay questions. Each week, participants were also asked to summarize in their own words a section of the module, describe the outcome of the exercises, and answer an interactive multiple-choice quiz. In the study, 19 speech-anxious high school students with SAD were randomly assigned to the intervention or a WLC group. Participants received a weekly email with therapist feedback. Significant improvements were found on measures of social anxiety, general anxiety, and depression, with a large effect size, and these were maintained at 1-year follow-up. No improvements were evident for social avoidance or quality of life measures.

Although large effects were evident in this study, it comprised a small sample of highly selected high school students, who were mostly females. Furthermore, only four participants completed more than two modules and none completed all nine modules during the study period. The authors argue that components central to obtaining therapeutic effects, such as cognitive restructuring, behavior experiments, exposure, modifying safety behaviors, and shifting of focus are provided early in the treatment, and that working on these components could lead to improvements despite limited exposure to the program.

Self-administered approaches for worry

Three self-administered approaches to treating pathological worry among college students were investigated in the study by Wolitzky-Taylor and Telch.Citation88 The study evaluated the efficacy of worry exposure, expressive writing, and relaxation consisting of pulsed audio-photic stimulation. There were 113 college students randomly assigned to one of the three interventions, which were practiced three times per week for 1 month, compared with a WLC. Academic worry and general anxiety were assessed at baseline, post-test, and at a 3-month follow-up. The pre- to post-treatment effect sizes for the primary outcome measure of academic worry were large for each of the three interventions and significantly larger than that observed for the WLC group. Each intervention led to significant reductions in general worry, with a large effect size for worry exposure and moderate effects for expressive writing group and audio-photic stimulation. Improvements in all three treatments continued at 3-month follow-up, with greater improvement from post-test to follow-up for the expressive writing group.

Treatment compliance was a concern in this study, with those in the audio-photic stimulation condition completing about two-thirds of the twelve assigned home practice sessions, whereas those assigned to worry exposure or expressive writing completed on average only about half of the sessions. The sample was primarily female and all college students.

CoolTeens

Only one trial was not an RCT, and this was a case series study investigating the CoolTeens CD-ROM,Citation15 which is a computerized self-help program adapted from previously validated bibliotherapy and group therapy programs.Citation15,Citation90 It has eight modules which each take 30–60 minutes to complete. Modules are designed to be completed on a weekly or fortnightly basis over an 8- to 12-week period. The trial was a very small sample study of only five participants diagnosed with anxiety, using a pre-post design. Significant positive outcomes were found for two of the participants, who were identified as having anxiety levels that had dropped to sub-clinical level at post-treatment. Two other participants showed positive gains in some areas, and one showed no change. Two participants no longer met the criteria for an anxiety disorder at the 3-month follow-up.

Excluded interventions

Some interventions that were excluded by the selection criteria are worth mention. The BRAVE interventions were excluded because of the high level of parental and trainer involvement. BRAVE for Children-ONLINE (8–12 year olds) and BRAVE for Teenagers-ONLINE (13–17 year olds), are anxiety treatment programs designed to treat SAD, generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, and specific anxiety disorders using CBT.Citation91 BRAVE for Children-ONLINE consists of 10 weekly sessions in the initial treatment schedule, backed up by a booster session at 1 and 3 months post intervention. There are also six sessions to be completed by parents. BRAVE for Teenagers-ONLINE consists of 13 weekly sessions, two booster sessions and seven parent sessions. In both interventions users are supported by a BRAVE trainer who helps guide and motivate users through the intervention by providing weekly contact via email and/or over the phone.Citation92 Specific techniques used within the program include relaxation training, identification of emotions and thoughts, positive self-talk, coping skills, problem solving, and approaching feared situations. A randomized-control study of BRAVE for Children-ONLINE found that the treatment had moderate levels of consumer satisfaction and high levels of credibility.Citation93 At post-treatment 30% of children in the trial group no longer met the criteria for an anxiety disorder, compared to 10% of children in the control group. At a 6-month follow-up, the number of children in the treatment group no longer meeting the diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder had risen to 75%, however the control group was not tested at this time so it is unclear exactly how much of this improvement can be attributed to the treatment program. Notably, at post-treatment only 60% of parents and one-third of children had completed the entire intervention. Initial studies of the teen program using case samples indicate that it can successfully be used to treat young people with anxiety.Citation92

The “Camp Cope-a-lot: The Coping Cat” CD-ROM is designed for children aged 7–12 years, and was excluded because it is designed to be used in conjunction with a mental health professional. It uses “Flash” animation and interactive activities with an inbuilt reward system to deliver CBT.Citation94 The guide character, “Charlie,” teaches users about anxiety, physiological symptoms, relaxation techniques, coping, and problem solving strategies, as well as walking users through step-by-step exposure tasks. The professional does not need to be trained or experienced in CBT, however. Initial case studies of the program have had positive outcomes.Citation95

Discussion

Surprisingly, the literature search revealed very little research evidence currently available regarding the effectiveness of self-help interventions to treat mild anxiety in young people. Although initially a large number of published papers were extracted from the database search, most of these did not meet the search criteria. In particular, very few studies were undertaken with young people specifically, and those that did focus on children or youth generally included considerable therapist involvement and could not be considered self-help. The six studies that remained showed mixed results, although most reported medium sized effects. These studies comprise a very poor evidence base for self-help for young people with anxiety; the outcomes were based mostly on findings with young adult female university students and had low treatment compliance and high attrition rates.

Similar methodological issues have been identified in reviews of self-help for anxiety with adults.Citation52,Citation55,Citation65,Citation74 Sample sizes were small, attrition rates were high, and little to no control was taken to prevent participants seeking outside treatment or medication. Whilst small to moderate improvements in anxiety symptoms were identified, the overall quality of the studies was poor. Consequently, all the evidence must be interpreted with caution.

Nevertheless, some important aspects of self-help interventions have been identified from the adult literature. Motivation of the user appears to be a very important aspect, with interventions that incorporate motivating tools, such as therapist or automatic reminders, having better outcomes than those that rely solely on the user.Citation71,Citation72,Citation80,Citation96 In particular, self-help programs that incorporate some form of therapist contact result in increased completion rates and improved outcomes when compared to pure self-help treatments,Citation96–Citation98 and traditional face-to-face interventions.Citation70,Citation76,Citation99–Citation103 It is possible that the improved outcomes occur because the user is more likely to be using a treatment that is appropriate for their individual issue.Citation72 Only minimal therapeutic input appears to be required, however, to provide appropriate advice and encouragement,Citation96 and this does not require the resources of highly skilled mental health professionals such as clinical psychologists.Citation68,Citation88,Citation90 Little to no improvements in anxiety symptoms have been noted by increasing therapist support to more than once weekly contact.Citation70,Citation104 Furthermore, fewer, shorter, more frequent modules appear to produce better outcomes as rewards may occur more frequently.Citation17,Citation80

Reviews with adults generally conclude that the best outcomes appear to be achieved by combining self-help treatments with some form of face-to-face therapy.Citation98,Citation105 Self-help interventions might be best utilized in stepped-care plans with some form of face-to-face interaction as a source of motivation, and initial assessment by a mental health professional.

Finally, it is important to note that the self-help interventions available to the public are unlikely to have undergone rigorous research testing, and those that have undergone testing are unlikely to be widely available for public use. The current review showed that self-help books and commercially available self-help resources for young people had not been the subject of research evaluation. The best research evidence was for university-designed and administered interventions that are not widely available to the public.

Recommendations

There is an urgent need for effective prevention and early intervention for anxiety disorders in children, adolescents, and young adults to prevent the widespread debilitating effects of such mental health problems and progression to more serious illness. A great deal of further research is needed, however, and attention needs to focus on reasons for the lack of rigorous research in the field and high attrition rates in the few research studies. Foremost, the many self-help interventions that are already available to the public need to be the subject of good quality outcome-based research. Furthermore, self-help interventions that are developed through university research trials need to be able to be publicly available if they are shown to be efficacious. The role of support in the use of self-help interventions also needs to be examined. Using self-help as an adjunct to therapy, or in a guided manner with the support of skilled or semi-skilled mental health professionals, is beginning to receive research attention. The role of parents in self-help for young people also needs to be investigated, however, particularly for children and younger adolescents, but also in relation to encouraging older adolescents to effectively use self-help interventions. Receiving appropriate and effective treatment as early as possible in the development of anxiety disorders is essential to improving the mental health and well-being of young people as they grow into adulthood. Ways to encourage research attention to this important area of early intervention need to be found.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MerikangasKRHeJPBursteinMLifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication – Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A)J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry2010491098098920855043

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th edWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association2000

- KesslerRCChiuWTDemlerOWaltersEEPrevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-Month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replicationArch Gen Psychiatry200562661762715939839

- KesslerRCBerglundPDemlerOJinRMerikangasKRWaltersEELifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replicationArch Gen Psychiatry200562659360215939837

- KesslerRCMerikangasKRBerglundPEatonWWKoretzDSWaltersEEMild disorders should not be eliminated from the DSM-VArch Gen Psychiatry200360111117112214609887

- LeonACOlfsonMPorteraLFarberLSheehanDVAssessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability ScaleInt J Psychiatry Med1997272931059565717

- DuchesneSVitaroFLaroseSTremblayRTrajectories of anxiety during elementary-school years and the prediction of high school noncompletionJ Youth Adolesc200837911341146

- Flannery-SchroederECReducing anxiety to prevent depressionAm J Prev Med2006316 Suppl 1136142

- KesslerRCBerglundPAFosterCLSaundersWBStangPEWaltersEESocial consequences of psychiatric disorders, II: Teenage parenthoodAm J Psychiatry199715410140514119326823

- KesslerRCFosterCLSaundersWBStangPESocial consequences of psychiatric disorders, I: Educational attainmentAm J Psychiatry19951527102610327793438

- FergussonDMWoodwardLJMental health, educational, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depressionArch Gen Psychiatry200259322523111879160

- StraussCCFrameCLForehandRPsychosocial impairment associated with anxiety in childrenJ Clin Child Psychol1987163235239

- FrydenbergELewisRTeaching coping to adolescents: When and to whom?Am Educ Res J2000373727745

- RickwoodDDeaneFPWilsonCJCiarrochiJYoung people’s help-seeking for mental health problemsAeJAMH200543 Suppl218251

- CunninghamMWuthrichVMRapeeRMLynehamHJSchnieringCAHudsonJLThe Cool Teens CD-ROM for anxiety disorders in adolescents: a pilot case seriesEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry200918212512918563472

- CampbellLFSmithTPIntegrating self-help books into psychotherapyJ Clin Psychol200359217718612552626

- HiraiMClumGASelf-help therapies for anxiety disordersWatkinsKEClumGAHandbook of Self-Help TherapiesNew York, NYRoutledge200877108

- AlbanoAMKendallPCCognitive behavioural therapy for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders: clinical research advancesInt Rev Psychiatry200214129134

- HerbertJDGaudianoBARheingoldAACognitive behavior therapy for generalized social anxiety disorder in adolescents: a randomized controlled trialJ Anxiety Disord200923216717718653310

- Cartwright-HattonSRobertsCChitsabesanPFothergillCHarringtonRSystematic review of the efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapies for childhood and adolescent anxiety disordersBr J Clin Psychol200443Pt 442143615530212

- TanielianTJaycoxLHPaddockSMChandraAMeredithLSBurnamMAImproving treatment seeking among adolescents with depression: understanding readiness for treatmentJ Adolesc Health200945549049819837356

- SladeTJohnstonATeessonMThe Mental Health of Australians 2: Report on the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and WellbeingCanberra AustraliaDepartment of Health and Ageing2009

- CheungAHDewaCSMental health service use among adolescents and young adults with major depressive disorder and suicidalityCan J Psychiatry200752422823217500303

- Oakley BrowneMAWellsJEScottKMMcGeeMALifetime prevalence and projected lifetime risk of DSM-IV disorders in Te Rau Hinengaro: the New Zealand Mental Health SurveyAust N Z J Psychiatry2006401086587416959012

- Australian Bureau of StatisticsNational Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of FindingsCanberra, AustraliaAustralian Bureau of Statistics2007

- US Surgeon GeneralMental Health: Culture, Race and Ethnicity – A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon GeneralRockville, MDUS Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services2001

- ZhangAYSnowdenLRSueSDifferences between Asian and White Americans’ help seeking and utilization patterns in the Los Angeles areaJ Community Psychol1998264317326

- EssauCAFrequency and patterns of mental health services utilization among adolescents with anxiety and depressive disordersDepress Anxiety200522313013716175563

- GulliverAGriffithsKMChristensenHPerceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic reviewBMC Psychiatry20101011321192795

- GouldMSVeltingDKleinmanMLucusCThomasJGChungMTeenager’s attitudes about coping strategies and help-seeking behavior for suicidalityJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiarty200443911241133

- WilsonCJDeaneFPCiarrochiJCan hopelessness and adolescents’ beliefs and attitudes about seeking help account for help negation?J Clin Psychol200561121525153916173086

- EisenbergDDownsMFGolbersteinEZivinKStigma and help seeking for mental health among college studentsMed Care Res Rev200966552254119454625

- CorriganPHow stigma interferes with mental health careAm Psychol200459761462515491256

- DeaneFPWilsonCJCiarrochiJSuicidal ideation and help-negation: Not just hopelessness or prior helpJ Clin Psychol200157790191411406803

- FallonBJBowlesTAdolescent help-seeking for major and minor problemsAust J Psychol19995111218

- ValkenburgPMSumterSRPeterJGender differences in online and offline self-disclosure in pre-adolescence and adolescenceBr J Dev Psychol201129225326921199497

- AngstJGammaAGastparMLepineJPMendlewiczJTyleeAGender differences in depression. Epidemiological findings from the European DEPRES I and II studiesEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci200225220120912451460

- KorpPHealth on the internet: implications for health promotionHealth Educ Res2006211788615994845

- KellyCMJormAFWrightAImproving mental health literacy as a strategy to facilitate early intervention for mental disordersMed J Aust20071877S26S3017908021

- RickwoodDDeaneFPWilsonCJWhen and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems?Med J Aust20071877S35S3917908023

- CiarrochiJHeavenPCSupavadeeprasitSThe link between emotion identification skills and socio-emotional functioning in early adolescence: a 1-year longitudinal studyJ Adolesc200831556558218083221

- BustonKAdolescents with mental health problems: what do they say about health services?J Adolesc200225223124212069437

- SayalKAnnotation: Pathways to care for children with mental health problemsJ Child Psychol Psychiatry200647764965916790000

- SawyerMGArneyFMBaghurstPAThe mental health of young people in Australia: key findings from the child and adolescent component of the national survey of mental health and well-beingAust N Z J Psychiatry200135680681411990891

- HolmesJMMarchSSpenceSHUse of the internet in the treatment of anxiety disorders with children and adolescentsCounselling, Psychotherapy, and Health200951187231

- SteinbergLSilverbergSBThe vicissitudes of autonomy in early adolescenceChild Dev19865748418513757604

- GriffithsKMChristensenHInternet-based mental health programs: a powerful tool in the rural medical kitAust J Rural Health2007152818717441815

- MoritzSWittekindCEHauschildtMTimpanoKRDo it yourself? Self-help and online therapy for people with obsessive-compulsive disorderCurr Opin Psychiatry201124654154821897252

- CalearALChristensenHReview of internet-based prevention and treatment programs for anxiety and depression in children and adolescentsMed J Aust201019211 SupplS12S1420528700

- BarakAKleinBProudfootJGDefining internet-supported therapeutic interventionsAnn Behav Med200938141719787305

- TateDFZabinskiMFComputer and Internet applications for psychological treatment: update for cliniciansJ Clin Psychol200460220922014724928

- BowerPRichardsDLovellKThe clinical and cost-effectiveness of self-help treatments for anxiety and depressive disorders in primary care: a systematic reviewBr J Gen Pract20015147183884511677710

- PantalonMVUse of self-help books in the practice of clinical psychologySalkovskisPAdults: Clinical Formulation and Treatment6New York, NYElsevier Science1998265276

- ElgarFJMcGrathPJSelf-administered psychosocial treatments for children and familiesJ Clin Psychol200359332112579548

- LewisGAndersonLArayaRSelf-help interventions for mental health problemsReport to the Department of Health R&D ProgrammeLondon, UK2004

- BrantleyJCalming Your Anxious Mind: How Mindfulness and Compassion Can Free You From Anxiety, Fear and PanicOakland, CANew Harbinger Publications2003

- RapeeRMWignallASpenceSHCobhamVLynehamHJHelping Your Anxious Child: A Step-by-Step Guide for Parents2nd edOakland, CANew Harbinger Publications2008

- RapeeRMAbbottMJLynehamHJBibliotherapy for children with anxiety disorders using written materials for parents: A randomized controlled trialJ Consult Clin Psychol200674343644416822101

- ChanskyTEFreeing Your Child From Anxiety: Powerful, Practical Solutions to Overcome Your Child’s Fears, Worries, and PhobiasNew York, NYBroadway Books2004

- CarterFCheesmanPAnxiety in Childhood and AdolescenceNew York, NYCroom Helm1988

- HiraiMClumGAA meta-analytic study of self-help interventions for anxiety problemsBehav Ther20063729911116942965

- MarksICavanaghKComputer-aided psychological treatments: evolving issuesAnn Rev Clin Psychol2009512114119327027

- CavanaghKShapiroDAComputer treatment for common mental health problemsJ Clin Psychol200460323925114981789

- Edwards-HartTChesterAOnline mental health resources for adolescents: overview of research and theoryAust Psychol2010453223230

- KaltenthalerEShackleyPStevensKBeverleyCParryGChilcottJA systematic review and economic evaluation of computerised cognitive behaviour therapy for depression and anxietyHealth Technol Assess20036221100

- CoullGMorrisPGThe clinical effectiveness of CBT-based guided self-help interventions for anxiety and depressive disorders: a systematic reviewPsychol Med201141112239225221672297

- MarrsRA meta-analysis of bibliotherapy studiesAm J Community Psychol19952368438708638553

- MencholaMArkowitzHSBurkeBLEfficacy of self-administered treatments for depression and anxietyProf Psychol Res Pr2007384421429

- ScoginFBynumJStephensGCalhoonSEfficacy of self-administered treatment programs: meta-analytic reviewProf Psychol Res Pr19902114247

- NewmanMGEricksonTPrzeworskiADzusESelf-help and minimal-contact therapies for anxiety disorders: Is human contact necessary for therapeutic efficacy?J Clin Psychol200359325127412579544

- MainsJAScoginFRThe effectiveness of self-administered treatments: a practice-friendly review of the researchJ Clin Psychol200359223724612552632

- BarakAHenLBoniel-NissimMShapiraNA comprehensive review and a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of internet-based psychotherapeutic inteventionsJ Technol Human Serv2008262–4109160

- CuijpersPMarksIMvan StratenACavanaghKGegaLAnderssonGComputer-aided psychotherapy for anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic reviewCogn Behav Ther2009382668220183688

- FletcherJLovellKBowerPCampbellMDickensCProcess and outcome of a non-guided self-help manual for anxiety and depression in primary care: a pilot studyBehav Cogn Psychother2005333319331

- HoldsworthNPaxtonRSeidelSThomsonDParallel evaluations of new guidance materials for anxiety and depression in primary careJ Ment Health199652195207

- CarrACGhoshAMarksIMComputer-supervised exposure treatment for phobiasCan J Psychiatry19883321121173365636

- NordinSCarlbringPCuijpersPAnderssonGExpanding the limits of bibliotherapy for panic disorder: randomized trial of self-help without support but with a clear deadlineBehav Ther201041326727620569776

- FebbraroGAAn investigation into the effectiveness of bibliotherapy and minimal contact interventions in the treatment of panic attacksJ Clin Psychol200561676377915546141

- WatkinsPLManualized treatment of panic disorder in a medical setting: two illustrative case studiesJ Clin Psychol Med Settings199964353372

- CarlbringPEkseliusLAnderssonGTreatment of panic disorder via the Internet: a randomized trial of CBT vs applied relaxationJ Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry200334212914012899896

- LidrenDMWatkinsPLGouldRAClumGAAsterinoMTullochHLA comparison of bibliotherapy and group therapy in the treatment of panic disorderJ Consult Clin Psychol19946248658697962893

- National Collaborative on Workforce and Disability (NCWD) For Youth2002 Available from: http://www.ncwd-youth.info/taxonomy/term/865Accessed November 11, 2011

- SethiSCampbellAJEllisLAThe use of computerized self-help packages to treat adolescent depression and anxietyJ Technol Human Serv2010283144160

- KenardyJMcCaffertyKRosaVInternet-delivered indicated prevention for anxiety disorders: a randomized controlled trialBehav Cogn Psychother2003313279289

- KenardyJMcCaffertyKRosaVInternet-delivered indicated prevention for anxiety disorders: six-month follow-upClin Psychol20061013942

- TillforsMAnderssonGEkseliusLA randomized trial of internet-delivered treatment for social anxiety disorder in high school studentsCogn Behav Ther2011402147157

- CukrowiczKCJoinerTEJrComputer-based intervention for anxious and depressive symptoms in a non-clinical populationCogn Ther Res2007315677693

- Wolitzky-TaylorKBTelchMJEfficacy of self-administered treatments for pathological academic worry: a randomized controlled trialBehav Res Ther201048984085020663491

- ChristensenHGriffithsKMKortenAWeb-based cognitive behavior therapy: analysis of site usage and changes in depression and anxiety scoresJ Med Internet Res200241e311956035

- CunninghamMWuthrichVExamination of barriers to treatment and user preferences with computer-based therapy using the Cool Teens CD for adolescent anxietyE J Appl Psychol2008421217

- SearsHAAdolescents in rural communities seeking help: who reports problems and who sees professionals?J Child Psychol Psychiatry200445239640414982252

- SpenceSHDonovanCLMarchSOnline CBT in the treatment of child and adolescent anxiety disorders: Issues in the development of BRAVE-ONLINE and two case illustrationsBehav Cogn Psychother2008364411430

- MarchSSpenceSHDonovanCLThe efficacy of an internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention for child anxiety disordersJ Pediatr Psychol200934547448718794187

- KhannaMAschenbrandSGKendallPCNew frontiers: computer technology in the treatment of anxious youthBehav Ther20073012225

- KhannaMSKendallPCComputer-assisted CBT for child anxiety: the coping cat CD-ROMCogn Behav Pract2008152159165

- GhoshAMarksIMCarrACTherapist contact and outcome of self-exposure treatment for phobias. A controlled studyBr J Psychiatry19881522342383048523

- SpekVCuijpersPNyklicekIRiperHKeyzerJPopVInternet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysisPsychol Med200737331932817112400

- KleinBRichardsJCAustinDWEfficacy of internet therapy for panic disorderJ Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry200637321323816126161

- CarlbringPNilsson-IhrfeltEWaaraJTreatment of panic disorder: live therapy vs. self-help via the InternetBehav Res Ther200543101321133316086983

- RichardsABarkhamMCahillJRichardsDWilliamsCHeywoodPPHASE: A randomised, controlled trial of supervised self-help cognitive behavioural therapy in primary careBr J Gen Pract20035376477014601351

- KiropoulosLAKleinBAustinDWIs internet-based CBT for panic disorder and agoraphobia as effective as face-to-face CBT?J Anxiety Disord20082281273128418289829

- KenwrightMLinessSMarksIReducing demands on clinicians by offering computer-aided self-help for phobia/panicBr J Psychiatry2001179545645911689405

- GreistJHMarksIMBaerLBehavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder guided by a computer or by a clinician compared with relaxation as a controlJ Clin Psychiatry200263213814511874215

- KleinBAustinDPierCInternet-based treatment for panic disorder: does frequency of therapist contact make a difference?Cogn Behav Ther200938210011319306149

- FarrandPDevelopment of a supported self-help book prescription scheme in primary carePrimary Care Mental Health2005316166