Abstract

A day treatment program was developed for patients suffering with severe work-related complaints who were unable to function at work because of this. The program consisted of a number of treatment modalities, including Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, protocolized nonverbal therapies, and activation. The main objective of all these therapies was to analyze participants’ personal qualities and vulnerabilities when functioning at work and to teach them new coping strategies and social skills to reduce their vulnerability in stressful situations. The results of the program were assessed in terms of scores on a number of self-rating questionnaires and hours spent at work. In a follow-up assessment one year after the original program had finished, we found a significant reduction in complaints and an increase in the number of hours spent on the job. At the start of the program, patients worked 25.2% of their contracted hours; a year later, this had increased to 77.3%. Even though this natural field study has its limitations, the results of the day treatment program seem very promising.

Keywords:

Introduction

Work is known to play an important role in psychological health and well-being.Citation1 Job dissatisfaction may lead to work-related stress and psychological and physical dysfunction. In The Netherlands, absence due to sickness caused by work-related psychological problems is a serious problem. About one third of cases where people are unable to work are the result of mental problems. In 36% of these cases, work pressure and work-related stress are the initial reasons for being absent from work, and 10% are caused by conflicts with colleagues, management, or both.Citation2

In The Netherlands, employees with health problems who are unable to continue working because of mental or physical complaints or both see their company physician. This physician either refers the patient elsewhere, orders sick leave, or does both. In the Dutch health care system, both the sick employee and the employer have to do everything in their power to improve the employee’s health. The employee’s wages (sometimes reduced) continue to be paid by the employer for a maximum period of 2 years. Treatment is paid for by the health care insurance system, as all Dutch inhabitants have obligatory health insurance.

Not only do stress and emotional exhaustion lead to impaired functioning on the job, but also to other problems, such as a significant increase in sickness-related absences.Citation3–Citation5 The most common work-related complaint is burnout, which has become a serious social problem from which approximately 4% of the Dutch working population suffer.Citation6

The term burnout is introduced as a metaphor for the work-related state of being emotionally exhausted and over-stressed. By definition, burnout complaints are associated with job dysfunction. People who complain of severe burnout are often unable to continue their normal work routines. Burnout is a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job, and is characterized by three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment.Citation7 The symptoms of burnout syndrome overlap with those of a number of other psychiatric syndromes, particularly depression and emotional exhaustion.Citation8 In a meta-analysis, Glass and McKnight concluded that burnout and depressive symptoms were not just synonyms for the same dysphoric state; nor were they mutually exclusive conceptsCitation9 (see alsoCitation8,Citation10–Citation12). Also, recent electroencephalography results for burnout patients have suggested burnout is a clinical syndrome in its own right.Citation13

Although severe burnout constitutes an emotional state with serious consequences for the individual, this syndrome has not – so far – been included in any psychiatric classification system. For this reason, professional staff members at mental health care institutions are often confused about accepting and understanding the diagnosis of burnout syndrome. Therefore, they are pragmatic in their choice of psychiatric diagnoses from a classification system and choose the syndrome that has the largest overlap of symptoms with burnout complaints. A commonly used definition in the diagnosis of burnout syndrome is the International Classification of Diseases (Tenth Revision) diagnosis of work-related neurasthenia,Citation8,Citation10,Citation14,Citation15 or alternatively that of undifferentiated somatoform disorder from the Fourth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), because all share the major problem of exhaustion.Citation16,Citation10

Although there is little empirical evidence of successful treatment of burnout, activation and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) are common treatment strategies.Citation8,Citation10 These are administered in outpatient clinics or in protocolized programs offered by specialized therapists. Patient benefits from this type of program vary greatly.

We developed a day treatment program for patients with severe work-related psychological complaints who were not expected to derive adequate benefit from an outpatient program or who desired a more intensive type of treatment. We included patients with different types of work-related psychological problems, not just people suffering from burnout.

The goal of the treatment was to analyze participants’ personal qualities and vulnerabilities when functioning on the job and to teach patients new coping strategies and social skills that would make them less vulnerable in stressful situations. In this paper, we will describe the program, its participants, and the first treatment results.

Questions

In this natural field study, we wanted to find answers to the following questions. First, is the program effective when measured with self-rating scales at three different assessment times, but also when expressed in terms of the number of hours spent on the job? Second, what patient characteristics, if any, are related to treatment outcome?

We investigated the duration of sick leave, the presence or absence of psychiatric disorders according to the DSM-IV, sex, age, education level, and method of referral to the hospital.

Treatment

A day treatment program was developed based on the principles of CBT combined with protocolized nonverbal therapies and activation. After referral, patients were included in the program by an experienced clinical psychologist. Patients were allowed to take part if they had a job to return to. Patients with severe psychiatric disorders (for example, suicidal tendencies or psychoses) were excluded from the study.

After an intake session, patients were individually assessed in three ways. First, they were interviewed by a medical resident using a standardized semistructured psychiatric interview, the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), to obtain a diagnosis according to the DSM-IV criteria.Citation16,Citation17 Second, a vocational rehabilitation worker interviewed the patients about their work-related history and work situation using a semistructured interview schedule. Finally, patients filled out a battery of psychological questionnaires aided by a computer program.

The treatment program was offered to groups of 5–8 participants and consisted of nine 8-hour days over 13 weeks. Treatment was offered in two 4-week periods, during which time the entire group spent a whole day on the treatment once every week. Between the two periods, one or two individual sessions were scheduled in another 4-week period. In these individual sessions, the first steps of the reintegration process were taken. After this intermezzo, participants were expected to be actively involved in their reintegration process and group treatment continued with the second period. The program finished by the end of the second period. Four weeks after the program ended, a booster day with cognitive therapy, a reintegration session, and psychological assessments completed the program. A follow-up session was scheduled to assess the effects of the treatment one year later. Patients filled out computer tests and participated in group sessions in which they reported about their work-related functioning.

The day program consisted of four 90-minute sessions. Between sessions, group members had coffee, tea, or lunch together without the therapists being present, making the total length of the treatment day 8 hours.

The first period

The program started with an introduction and psychoeducation, followed by psychomotor therapy, which was included for several reasons. Activation is known to be an effective treatment modality for people with burnout complaints.Citation10 For this reason, a protocol was developed in which different aspects of working situations were practiced, such as cooperating with other people, coping with limited energy levels, and dealing with work pressure. These sessions were videotaped for feedback in the next session.

Cognitive therapy is an important part of the treatment, as is stress management (including time management and lifestyle aspects). In the first period, both strategies were included in the treatment every day.Citation10 The qualities and limitations of patients’ functioning on the job were investigated and discussed in two additional sessions. Role playing was frequently used, together with videotaped feedback. One reintegration session was also scheduled to prepare patients for the reintegration steps that were to follow the next period.

Between periods

After the first 4-week treatment period, a 4-week period without a group program was scheduled, in which participants took the first steps toward their reintegration process. One or two individual therapeutic sessions supported these steps.

The second period

After this intermezzo, the second part of the group program focused on aspects of the participants’ personalities that influence their functioning on the job. In additional sessions, interpersonal strategies related to coping with conflicts were employed using role play and videotaped feedback. Cognitive therapy continued during the second period. Art therapy was used as a nonverbal treatment procedure to gain insight into different aspects of functioning in a job (cooperating with other people, working with a dominant colleague, protecting their position, etc). Finally, sessions were held concerning the actual reintegration process and developing a relapse prevention plan, which was designed to protect participants from future relapses. Participants were also encouraged to look for a “job coach” from their own social circle who would be able to support them in their reintegration process during the following months.

Assessment procedures

In addition to the standardized interview used to assess a diagnosis from the DSM-IV, the following questionnaires were filled out.

UBOS

The Utrechtse Burnout Schaal (UBOS) is the Dutch version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory, which assesses job-related burnout complaints using three subscales: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and lack of professional accomplishment. These items all refer to the work situation.Citation18,Citation19

SFQ

The Shortened Fatigue Questionnaire (SFQ) is a short, reliable, and easy-to-use instrument to determine the intensity of patients’ bodily fatigue.Citation20

BDI-II-NL

The BDI-II-NL, the Dutch version of the Beck Depression Inventory, was used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms.Citation21,Citation22

SCL-90-R

The Symptom Checklist-90 Revised version is a self-report inventory designed to screen subjects for psychological distress and global psychopathology during the previous week.Citation23,Citation24 In addition to an overall score, this instrument contains eight subscales: anxiety, agoraphobia, depression, somatization, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, paranoid ideation, hostility, and sleeping problems.

IOA

The Inventarisatielijst Omgang met Anderen (IOA) is a self-rating questionnaire used to assess social skills in two ways:Citation25 (1) the frequencies with which social skills are used in different social situations and (2) tensions experienced by the patient when social skills are used.

UCL

The Utrechtse Coping Lijst (UCL) is a self-report questionnaire that assesses the way people generally react if confronted with problems or unpleasant situations.Citation26 It contains seven independent subscales: active problem focusing (analyzing problems, acting confidently and in a purposeful way), palliative reaction pattern (looking for distraction, relaxation, seeking diversions), avoidance (avoiding involvement, adopting a waiting attitude), support-seeking (seeking comfort and sympathy), worrying (being preoccupied with problems, brooding, feeling unable to act), emotional expression (showing frustration), and comforting cognition (self-encouragement, creating soothing thoughts).

These psychological self-report questionnaires were filled out three times – before the start of the program, at the booster session at the end of the program, and during the follow-up procedure 1 year after the program had finished.

The actual hours participants went to work were registered at these assessment moments.

Participants

One hundred and seventy patients with severe work-related complaints started the program (83 males, average age 43.7 (±8.5) years; 87 females, average age 42.4 (±9.5) years); 14 dropped out and did not complete the program. Seven patients failed to attend the booster session and also missed the second psychological assessments. Thus, 149 patients completed both the program and the second assessment. Ninety-nine patients participated in the follow-up session. Twenty-seven patients failed to participate in this evaluation and 23 patients finished the program less than a year ago and were therefore excluded from the present study.

In the results section, we present data from all 170 patients who started the program. The calculations shown are from the 99 participants who were assessed three times (52 males, average age 44.4 (±8.2) years; 47 females, average age 42.9 (±9.3) years). Of these, 48.7% met the criteria of one or more DSM-IV diagnoses, as assessed using the MINICitation16 depression, 12.8%; dysthymia, 10.3%; panic disorder, 3.8%; post-traumatic stress disorder, 1.32%; alcoholism, 2.6%; agoraphobia, 6.4%; social phobia, 5.1%; obsessive compulsive disorder, 6.4%; bulimia, 1.3%; and general anxiety disorder, 21.8%).

Sick leave varied from 0–110 weeks, with a mean of 30.4 weeks (±27.5) and a median of 21 weeks. Education levels were: low, 18.2%; middle, 32.3%; and high, 49.5%. Marital status was: married, 53.5%; divorced, 9.1%; living alone, 26.3%; living with a partner, 26.3%; living with a partner and child(ren), 41.4%; living with child(ren), 5.1%; and living with another person, 1%. Referral method was: occupational physicians, 34.3%; psychiatrist or psychologist, 29.3%; general practitioners, 29.3%; and others, 7.2%.

Most, but not all, participants suffered from burnout. Of the participants, 85% showed symptoms of emotional exhaustion, according to their UBOS scores, which differed from the scores in a normal population.Citation18

Statistics

Mean and median scores and effect sizes d, were calculated and a repeated measures ANOVA was used to calculate significance levels.Citation27

Results

We found a statistically significant reduction of complaints over time. The effect sizes of mood and energy scores on the questionnaires in particular are large (see ). An effect size of 0.5 is considered to be a medium effect, and 0.8 or higher is a large effect.Citation27 Social skills and behavior were also seen to improve over time. Coping strategies improved only very slightly to moderately.

Table 1 Results of the day treatment program for people with severe work-related complaints based on three assessments during and after the program

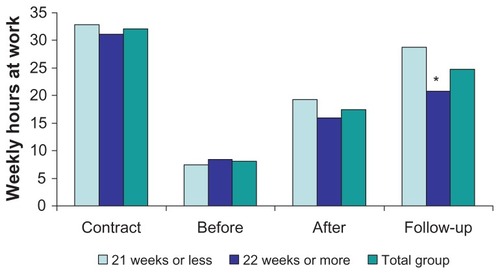

Of the participants, 77.3% had reintegrated into their jobs and kept the original contract hours a year after finishing the program (see ).

Figure 1 Duration of sick leave: short versus long.

Participants whose sick leave does not exceed 21 weeks’ duration show significantly better reintegration results after a year than those whose sick leave lasts more than 21 weeks. Patients with a combination of work-related problems and a psychiatric disorder show the same results as participants without psychiatric disorders. Sex, age, education level, and the method of referral did not influence the results in any way.

Discussion

This report describes a short but intensive day treatment program and its results for patients suffering from severe work-related psychological problems. Although all patients’ complaints were work-related, their symptoms were heterogeneous. Emotional exhaustion was common, but patients complaining of difficulties in conflict management without fatigue were also included. This protocolized program had as its main objective to reduce patients’ complaints and to teach patients new and more effective coping strategies. Besides the lack of homogeneity in complaints, it is also unclear whether one single intervention is responsible for treatment outcome. The program contained different training strategies and social skills exercises designed to reduce patients’ vulnerability in future stressful situations, such as CBT interventions, nonverbal therapeutic interventions, and activation. All these interventions highlighted different aspects of stress on the job and offered ways how to deal with this, which resulted in a personal relapse prevention plan at the end of the program. De Vente et al concluded that CBT-based interventions are unsuccessful in the treatment of patients suffering from clinical levels of work-related stress.Citation28 These findings are in line with those of Blonk et al, who compared an extensive CBT therapy, a treatment with brief CBT-derived interventions combined with individual-focused and workplace interventions, and a control group of people with severe work-related psychological complaints.Citation29 The combination treatment was found to be superior to both CBT and the control group in that it shortened the duration of sick leave. This last finding is probably in line with our own results since, in our program, it is not possible to discriminate between the effects of the different elements of the treatment. In our program, the total package of interventions may be responsible for the therapeutic outcome. However, it is not possible to identify a single element of the program that causes the effect.

Patient preferences for the distinctive elements differed, but they were satisfied with the treatment as a whole and with the opportunity to share their experiences in a group setting.

When looking at the figures relating to the follow-up assessment that was held a year after the program had ended and comparing these to the initial figures, a significant reduction of symptoms was found and patients’ job performance amounted to 77.3% of the hours specified in their contracts. Before the start of the program, patients had been absent from their jobs for approximately 30 weeks on average. We therefore conclude that the effects of this program seem promising.

Coping strategies hardly improved at all or only very slightly. Van Rhenen et al showed that active coping strategies are related to the duration of the sick leave.Citation30 We were unable to confirm these findings. However, there are some differences between our study and that of Van Rhenen et al. In our study, participants mainly suffered from burnout, whereas in the Van Rhenen study, the whole population of a major company was investigated. In our study, the initial mean scores of coping strategies did not differ from the mean scores of a normal population, according to the manual of the UCL.Citation26 Therefore, the possibility of significantly improving coping strategies is not very realistic. Nevertheless, the changes we found are in the desired direction.

There are some limitations to this study. As previously mentioned, this is a natural field study with a lack of homogeneity in the population and without a single intervention technique that is responsible for the effects. Since we did not use a placebo condition, it is still possible that the therapeutic results are not superior to any effects over time without treatment. Therefore, it is impossible to draw conclusions about the working mechanisms of the program.

This program was developed for and used with patients in a regular mental health care situation instead of in a randomized, controlled laboratory situation. This might increase its chance of being implemented in everyday mental health care practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Josie Borger for improving the English and to Harry Blijleven, Ludi de Wolff, Roos den Held, Tineke Demmer, and Marco Bluming for their participation and input in the project.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BlusteinDLThe role of work in psychological health and well-beingAm Psychol20086322824018473608

- Bakhuys RoozeboomMGouwPHooftmanWHoutmanIKlein HesselinkJArbobalans 2007/2008. Kwaliteit van de arbeid, effecten en maatregelen in Nederland [Arbobalans 2007/2008. Quality of Labour, Effects and Measures in the Netherlands.]HoofddorpTNO Kwaliteit van Leven2009

- MaslachCSchaufeliWBHistorical and conceptual development of burnoutSchaufeliWBMaslachCMarekTProfessional burnout: recent developments in theory and researchWashington DCTaylor and Francis1993116

- TarisTWIs there a relationship between burnout and objective performance? A critical review of 16 studiesWork & Stress200620316334

- BekkerMHJCroonMABressersBChildcare involvement, job characteristics, gender and work attitudes as predictors of emotional exhaustion and sickness absenceWork & Stress200519221237

- BakkerABSchaufeliWBDemeroutiEJanssenPPMVan der HulstRBrouwerJUsing equity theory to examine the difference between burnout and depressionAnxiety Stress Coping200013247268

- MaslachCSchaufeliWBLeiterMPJob BurnoutAnnu Rev Psychol20015239742211148311

- SchaufeliWEnzmannDThe Burnout Companion To Study And PracticeA Critical AnalysisLondonTaylor and Francis Ltd1998

- GlassDCMcKnightJDPerceived control, depressive symptomatology, and professional burnout: a review of the evidencePsychol Health1996112348

- SchaapCPDRKeijsersGPJVossenCJCBoelaarsVAJMHoogduinCALBehandeling van burnoutHoogduinCALSchaufeliWBSchaapCPDRBakkerABBehandelstrategieën bij burnoutHouten/DiegemBohn Stafleu Van Loghum2001

- BakkerASchaufeliWVan DierendonkDBurnout: prevalentie, risicogroepen en risicofactorenHoutmanIDSchaufeliWBTarisTPsychische vermoeidheid en werkAlphen aan den RijnSamsom2000

- AholaKHonkonenTIsometsäEThe relationship between job-related burnout and depressive disorders – results from the Finnish 2000 StudyJ Affect Disord200588556216038984

- van LuijtelaarGverbraakMVan den BuntMKeijsersGArnsMEEG findings in burnout patientsJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci20102220821720463115

- World Health Organisation De ICD-10Classificatie van Psychische Stoornissen en GedragsstoornissenKlinische beschrijvingen en diagnostische richtlijnen Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie, Hengeveld MHLisseSwets en Zeitlinger1994

- SchaufeliWBBakkerABHoogduinKSchaapCKladlerAOn the clinical validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory and the burnout measurePsychol Health200116565582

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th edWashington DCAmerican Psychiatric Association1994

- SheehanDVLecrubierYSheehanKHThe Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10J Clin Psychiatry199859Suppl 2022339881538

- SchaufeliWBVan DierendonckDUBOS: Utrechtse Burnout SchaalManual [Utrecht BurnOut Scale]LisseSwets and Zeitlinger BV2000

- MaslachCJacksonSEThe measurement of experienced burnoutJournal of Occupational Behaviour1981299113

- AlbertsMSmetsEMAVercoulenJHMMGarssenBBleijenbergGVerkorte vermoeidheidsvragenlijst: een praktisch hulpmiddel bij het scoren van vermoeidheidNederlands Tijdschrift voor de Geneeskunde199714115261530

- BeckATSteerRABrownGKManual for the Beck Depression Inventory-IISan Antonio, TXPsychological Corporation1996

- BeckATSteerRABrownGKBeck Depression Inventory-IIDutch version: Van der Does AJWLisseSwets Test Publishers2002

- DerogatisLRSCL-90: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual-I for the R(evised) VersionBaltimore, MDJohns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Clinical Psychometrics Research Unit1977

- ArrindelWAEttemaJHMSymptom Checklist SCL-90ManualLisseSwets and Zeitlinger BV2003

- Van Dam-BaggenCMJKraaimaatFWInventarisatielijst Omgaan met Anderen IOAManual [Inventory of Interpersonal Situations]LisseSwets and Zeitlinger BV1987

- SchreursPJGVan de WilligeGBrosschotJFTellegenBGrausGMHDe Utrechtse CopingLijst: UCLManual [Utrecht Coping List]LisseSwets and Zeitlinger BV1993

- CohenJStatistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural SciencesHillsdale, NJLawrence Erlbaum1988

- De VenteWKamphuisJHEmmelkampPMGBlonkRWBIndividual and Group cognitive-behavioral treatment for work-related stress complaints and sickness absence: a randomized controlled trialJ Occu Health Psychol200813214231

- BlonkRWBrennikmeijerSLagerveldSHoutmanILDReturn to work: a comparison of two cognitive behavioural interventions in cases of work-related psychological complaints among the self-employedWork & Stress200620129144

- Van RhenenWSchaufeliWBVan DijkFJHBlonkRWBCoping and sickness absenceInt Arch Occup Environ Health20088146147217701200