Abstract

Background

Previous literature has asserted that family meals are a key protective factor for certain adolescent risk behaviors. It is suggested that the frequency of eating with the family is associated with better psychological well-being and a lower risk of substance use and delinquency. However, it is unclear whether there is evidence of causal links between family meals and adolescent health-risk behaviors.

Purpose

The purpose of this article is to review the empirical literature on family meals and adolescent health behaviors and outcomes in the US.

Data sources

A search was conducted in four academic databases: Social Sciences Full Text, Sociological Abstracts, PsycINFO®, and PubMed/MEDLINE.

Study selection

We included studies that quantitatively estimated the relationship between family meals and health-risk behaviors.

Data extraction

Data were extracted on study sample, study design, family meal measurement, outcomes, empirical methods, findings, and major issues.

Data synthesis

Fourteen studies met the inclusion criteria for the review that measured the relationship between frequent family meals and various risk-behavior outcomes. The outcomes considered by most studies were alcohol use (n=10), tobacco use (n=9), and marijuana use (n=6). Other outcomes included sexual activity (n=2); depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts (n=4); violence and delinquency (n=4); school-related issues (n=2); and well-being (n=5). The associations between family meals and the outcomes of interest were most likely to be statistically significant in unadjusted models or models controlling for basic family characteristics. Associations were less likely to be statistically significant when other measures of family connectedness were included. Relatively few analyses used sophisticated empirical techniques available to control for confounders in secondary data.

Conclusion

More research is required to establish whether or not the relationship between family dinners and risky adolescent behaviors is an artifact of underlying confounders. We recommend that researchers make more frequent use of sophisticated methods to reduce the problem of confounders in secondary data, and that the scope of adolescent problem behaviors also be further widened.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

Adolescence can be a time of turbulence, and primary challenges to adolescent health in the US are the health-risk behaviors that members of this age-group choose to engage in.Citation1 Thus, there is substantial interest on the part of families, communities and policy makers in identifying effective protective factors against adolescent health-risk behaviors.

In recent years, family meals have been heralded as a key protective factor for adolescents in the popular press,Citation2,Citation3 by policy groups, and by scientific researchers. There is a substantial literature that finds that eating with the family more frequently is associated with better psychological well-beingCitation4–Citation8 and a lower risk of substance use and delinquency.Citation4,Citation5,Citation7,Citation9–Citation13 Such findings have inspired community-, state-, and national-level programs that promote the concept of regular family meals, eg, the Family Day program initiated by the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (http://www.casafamilyday.org).Citation11 Numerous mechanisms via which family meals can improve adolescent well-being have been posited. For example, family meals may give adolescents and their parents the opportunity to converse, exchange ideas, discuss feelings, and thereby reinforce familial bonds.Citation14,Citation15 Conversations at the dinner table may also give parents the opportunity to learn what is going on in their children’s lives.Citation11 Family meals might also facilitate parental monitoring and reduce time spent away from parental supervision.Citation10,Citation14–Citation16

At the same time, it must be recognized that families who select to have meals together may be different in other difficult-to-measure ways than families who do not. For example, families that eat together may have better interpersonal relationships or more vigilant parents to begin with, whereby family meals may merely serve as a proxy measure of those factors, and may not in themselves significantly impact any adolescent health or behavioral outcome. Moreover, adolescents are likely to have more autonomy than younger children in deciding whether to participate in family meals. Hence, it may be that adolescents who are well adjusted and less prone to delinquent behaviors are the ones who eat more frequently with their families. Thus, it is important to consider adjusting for these factors using the best available empirical methods, so as to better assess whether family meals, ceteris paribus, protect against adolescent risk behaviors.

For this article, we did a qualitative systematic review of the empirical literature on family meals and adolescent health behaviors and outcomes in the US. Our purpose was to inform on which risk behaviors are most frequently looked at in the literature, how rigorously potential confounders were adjusted for, and how frequently statistically significant associations were detected between family meals and the outcome of interest.

Specifically, we considered quantitative studies where the primary “treatment” of interest was family meals (including breakfast, lunch, or dinner), and the outcome of interest was an adolescent risk behavior. While the age range of adolescence often varies in definition, for this review we include studies whose participants were anywhere between the ages of 11 and 18 years.Citation17 The range of risky behaviors encompasses substance use, sexual activity, violence and delinquency, school performance, depression and suicide ideation, general risky behaviors, and well-being, but for the purposes of this review we exclude outcomes related to obesity, dieting patterns, or eating disorders. We summarize our findings, and report on the empirical methods used, with specific focus on whether available empirical methods to minimize the effects of confounders in observational data were used.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

We followed all of the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement that were applicable to our study.Citation18 Computer-based searches were conducted of the following academic databases: 1) Social Sciences Full Text (coverage: 1983 to present); 2) Sociological Abstracts (coverage: 1952 to present); 3) PsycINFO® (coverage: 1806 to present); and 4) PubMed/MEDLINE (coverage: 1946 to present). We used various combinations of keywords relating to family meals and selected risk-behavior outcomes to maximize search results. We searched each database with search terms to identify articles that suggested a family interaction (ie, “family,” “parents,” “mother,” “father” in combination with “adolescence,” “adolescent,” “teen,” “young adult,” “juvenile,” “youth”). To capture this family interaction in the context of the family meal, additional keywords were used (ie, “meals,” “breakfast,” “lunch,” “dinner,” “eating,” “dining”). In addition, outcomes were captured using variations of such keywords as “risky behaviors,” “depression,” “violence,” “delinquency,” “unintentional injury,” “suicide,” “drug use,” “substance use,” “alcohol use,” “tobacco use,” “smoking,” “drinking,” “sexual behaviors,” “unintended pregnancy,” “sexually transmitted diseases,” “school,” and “well-being.” A complete list of search terms can be found in .

Table 1 Keywords used to search the literature on family meals and adolescent risk behaviors

Study selection

We conducted a systematic search for studies that reported quantitative empirical data assessing the relationship between family meals and risk behaviors in adolescents published between January 1990 and September 2013. Additional inclusion criteria included articles published in the English language and conducted in the US. Only studies conducted in the US were included. This is because perceptions about what adolescent “risk behaviors” are may differ across countries, eg, anecdotal evidence suggests that children in France are often permitted to consume wine by their parents and guardians, and moderate alcohol consumption is not viewed as a “problem” per se.Citation19 We wanted to ensure some consistency in defining problem behaviors. Additionally, there may be certain different cultural connotations about what occurs during family meals, such as the nature of the conversation, which may differentially moderate the relationship between family meals and problem behaviors for different cultures. Hence, we took the approach of confining our studies to the US.

In order to determine study eligibility, two reviewers (SG and WT) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of all citations identified in the search for possible inclusion. Any differences between reviewers were resolved by consensus, and when necessary, discussion with the senior author (BS). For the studies that met the inclusion criteria, the full text was retrieved and obtained for independent assessment. The primary reasons for exclusion from this review were that the studies were nonempirical, conducted outside the US, or not relevant to our review. Examples of articles identified as not relevant to our review included articles that did not did not use an adolescent risk behavior as an outcome, did not capture family involvement in terms of family mealtime, and articles where family meals were the outcome rather than the main covariate of interest.

Agreement between reviewers was assessed with Cohen’s κ coefficient.Citation20 This statistic measures agreement on a scale of 0 to 1, where 0 represents agreement or disagreement simply by chance and 1 represents perfect agreement.Citation21 Cohen’s κ coefficient was calculated using GraphPad (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).Citation22 Fourteen studies were identified that met our inclusion criteria.Citation5–Citation10,Citation12,Citation23–Citation29

Data extraction

The full text of each article that met our inclusion criteria was reviewed. Data extraction and entry was performed using a serial review process. The primary reviewer (SG) extracted data from each article and entered the information into a standardized database under the major headings of Sample, Study design, Family meals measurement, Outcomes, Empirical methods, Findings, and Major issues. The extracted data were reviewed for accuracy by the second reviewer (WT).

Results

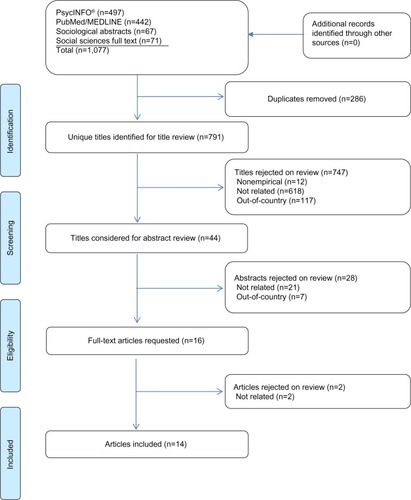

illustrates the literature review and search process used to identify the 14 studies included in this review from an initial yield of 1,077 citations. The initial search yielded 791 studies after removing duplicate citations. After applying the restrictions for inclusion, 747 studies were excluded upon title review, 28 studies were excluded upon abstract review, and two studies were excluded upon full-text article review. The two reviewers achieved good agreement in the initial review of titles for inclusion (κ=0.79, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.68–0.91), very good agreement on the review of abstracts for inclusion (κ=0.87, 95% CI: 0.73–1.00), and perfect agreement on the review of full-text articles (κ=1.00, 95% CI: 1.00–1.00).

Figure 1 Family structure and risk behaviors: the role of the family meal in assessing likelihood of adolescent risk behaviors flowchart.

We summarize the final list of studies, data sets used, measures of family meals, outcomes, empirical approaches, and significant results in .

Table 2 Study details and main effects of family meals on adolescent risk-behavior outcomes

Family meal measurement

The main covariate of interest in the final list of studies was family meals. Four studies measured the family meal variable continuously,Citation8,Citation10,Citation28,Citation29 six measured it category cally,Citation5,Citation7,Citation9,Citation12,Citation23,Citation24 two measured it both ways,Citation6,Citation25 and two measured it experimentally.Citation26,Citation27 Of these studies, eight asked about the frequency of family dinner in particular,Citation6–Citation8,Citation10,Citation12,Citation24,Citation25,Citation28 five asked about the frequency of family meals in general,Citation5,Citation9,Citation23,Citation26,Citation27 and one asked about the priority of family meals.Citation29 Of the studies that categorically recoded the family meal/dinner variable, five or more meals was typically considered to be “regular” or “frequent.”Citation6,Citation7,Citation9

Outcomes

As can be seen from , ten studies examined the relationship between frequent family meals (FFM) and adolescent alcohol use; nine studies examined the relationship between FFM and adolescent tobacco use; six studies examined the relationship between FFM and adolescent marijuana use, and two of those studies additionally examined the relationship between FFM and other illicit drug use, including cocaine products, inhalants, and other illegal drugs. Substantial variation existed in how the outcomes were measured. For example, three studies measured alcohol use in the past year, four measured use in the past month or two weeks, and two had general questions related to alcohol initiation, frequency, stage of uptake, and/or binge drinking. One longitudinal study asked about initiation and frequency of use since the last interview and in the last year. Similarly, three studies measured tobacco use in the past year, four measured use in the past month or daily, one used a general question related to tobacco initiation and frequency, and one longitudinal study asked about initiation and frequency of use since the last interview and in the past year.

Three studies measured the association between FFM and adolescent sexual activity. One examined sexual initiation, and one study examined if the respondent had engaged in frequent sexual activity (three or more times). Five studies investigated the relationship between FFM and adolescent depression and/or suicide ideation/attempts. Three studies measured depressive symptoms in the past week or month, and two measured both depressive symptoms and suicide ideation or attempts. Six studies measured the impact of family meals on measures related to adolescent well-being. Three studies measured issues related to positive identity (eg, self-esteem, sense of purpose, positive view of personal future), one measured perceived stress, and two measured several aspects of emotional well-being (eg, “positive affect” or feelings of well-being, “negative affect” or feelings of distress/stress, and “engagement” or feelings of enjoyment in activities). Four studies addressed FFM and adolescent violence and delinquency, which included acts of aggression/violence (eg, fighting, carrying a weapon, causing physical harm) and delinquency/antisocial behavior (eg, shoplifting, stealing, vandalism, trouble with law-enforcement officials). Finally, two studies considered the relationship between FFM and school-related issues, with one considering academic performance (eg, most common grade received) and the other considering school problems (eg, less than C grade point average, skipping school).

Empirical approach and significant findings

In , we summarize the frequency with which the association between FFM and each outcome of interest was analyzed. If a paper included several analyses, eg, using different measures of FFM or the outcome, included both cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis, or stratified analysis by sex or other characteristics, then each of those is counted as a separate analysis. We also summarized the number of times the relationship was estimated using unadjusted models, using models that controlled for standard demographic and family characteristics, using models that additionally controlled for other measures of family/parental connectedness, and using models that used advanced empirical techniques to minimize bias arising from confounders. The standard demographic characteristics typically included the adolescent’s sex, race/ethnicity, age and/or school grade, family structure, and one or more indicators of socioeconomic status, such as parental education, household income, or eligibility for public assistance. Models that adjusted for family/parental connectedness took various approaches, eg, Eisenberg et alCitation5,Citation9 controlled for family connectedness using four survey items on adolescent perceptions of how much each parent cared for them, and how well they could talk to each parent about problems; Pearson et alCitation28 controlled for quality of parent–child relationships, other shared family activities, and parent-reported communications with the adolescent about sex; Fulkerson et alCitation7 controlled for family support, positive family communications, parental involvement in school, family rules and boundaries, and positive adult role models. SenCitation10 controlled for other family activities, and parental awareness of the adolescent’s friends, teachers, school activities, and who the adolescent is with when not at home; Musick and MeierCitation8 controlled for global family relationship quality, parent–child family relationship quality, other activities with parents, arguments with parents, and the extent of parental control. Hoffmann and WarnickCitation25 used “balanced” control and treatment samples on parent–child relationships based on a 16-question scale, and the same parental awareness questions as Sen.Citation10

Table 3 Frequency of significant associations between family meals and outcomes of interest

Finally, with respect to more advanced techniques for minimizing the problem of confounders, Hoffmann and WarnickCitation25 used a propensity score-matching approach, and balanced their treatment and control samples by using parent–child relationship quality, parental awareness, composite scores to measure the quality of the home and neighborhood environment, and the time the adolescent spends on other activities like homework, reading for pleasure, and television viewing. SenCitation10 used the frequency of family dinners in year t + 1 as a proxy variable for the adolescent’s propensity to spend mealtimes with families. Musick and MeierCitation8 estimated “first-difference” models utilizing the difference in outcomes as well as in family dinner frequency between two waves of data for the same adolescents. Thus, essentially, both SenCitation10 and Musick and MeierCitation8 used approaches that would account for the adolescent’s unmeasured and time-invariant individual characteristics that could otherwise confound the relationship between FFM and the outcomes of interest.

Alcohol use was the outcome analyzed the largest number of times (57 times), followed by violence/delinquency (53 times), tobacco use (43 times), marijuana/illicit drug use (38 times), depression/suicide ideation (34 times), and well-being (32 times). Sexual activity and school-related issues were each analyzed only eight times. The associations between FFM and the outcome in question were most likely to be statistically significant with unadjusted models or univariate analyses. Associations were less likely to be significant in models that controlled for demographic and family characteristics or family/parental connectedness. When methods like propensity score matching were used, no significant associations were found between FFM and alcohol or tobacco use. When methods to control for time-invariant individual characteristics were used, the associations were significant about half the time for substance use, five of 16 times for violence/delinquency, and two of two times for depression/suicide ideation. Notably, no analyses were identified that applied either propensity score matching or controlling for time-invariant individual characteristics to outcomes like sexual activity, school-related issues, and well-being.

Discussion

We reviewed 14 studies to examine the relationship between family meals and adolescent risk behaviors. The most commonly measured outcomes in this literature center on adolescent substance use, well-being, depression/suicide, and violence/delinquency. Many studies found significant associations between FFM and these categories; however, results differed by sex and also by the empirical approach used.

This review was conducted with a particular emphasis on the empirical methods used in the literature. The challenge is establishing plausible causal links between family meals and adolescent health outcomes. The most widely accepted scientific approach for establishing causality, randomized controlled trials, does not seem feasible in this research area, both because any “effects” of family meals on risky behaviors are unlikely to manifest themselves in the relative short run, and because of the ethical challenges inherent in a randomized controlled trial study design if it means that the “control group” will not be permitted to participate in family meals for the study period. However, there exists a rich array of other empirical methods that can be applied to infer causality plausibly, even with observational data.Citation30,Citation31 We found that most analyses in this literature controlled for basic demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, sometimes also adding on other measures of family connectivity. Only a limited number of analyses used available empirical methods that help limit confounders like unmeasured individual-level characteristics. Moreover, there were no analyses using such approaches for outcomes like early sexual activity, school-related issues, and well-being, and only two analyses using them for depression/suicide ideation.

Other potential empirical approaches that could be explored to minimize the effect of confounders include methods like sibling fixed effects, which have been applied to control for family-level confounders in areas like socioeconomic consequences of adolescent motherhood.Citation32 Alternatively, researchers may also look for exogenous shocks that can influence the ability to eat together as families, and use the “instrumental variables” approach to control for confounders.Citation33 Yet another approach, recently utilized in a study on breastfeeding and obesity,Citation34 is randomizing families to treatment groups that are actively informed on the benefits of family meals versus control groups, and then using the randomization as an instrument.

Apart from utilizing the most sophisticated techniques available for addressing the problem of confounders in secondary data analysis, we argue that this field of research may also benefit by expanding the scope of risky adolescent behaviors considered. For example, the number of US high school adolescents who have ever tried “electronic cigarettes” or “e-cigarettes” has doubled from about one in 20 in 2011 to one in ten in 2012.Citation35 While it is assumed that e-cigarettes come without the toxic effects of tobacco smoking, there is a general lack of research and understanding about the health risks.Citation36–Citation38 There are also other, well-established adolescent risk behaviors that have not been well explored in the context of family meals, such as risky driving behavior. It is well established that adolescents frequently engage in risky driving behaviors, such as riding in a car without a seat belt on, driving under the influence, or texting while driving.Citation39–Citation41 Given that the rate of fatal motor vehicle accidents is higher among teens than other age-groups, and that many teenagers involved in fatal car crashes have been found to have been engaged in risky driving behaviors,Citation42 and given that eating together may provide an opportunity for parents to discuss these issues with their children, it is somewhat surprising that the family meal literature has not looked at the association between family meals and engaging in risky driving behaviors. Other adolescent risk-behavior outcomes worthy of further examination include abuse of prescription drugs, use of specific illicit drugs, intimate partner violence history, and specific problem behaviors in school (eg, school suspensions/expulsions, repeating a grade).

We acknowledge certain limitations in our study. Our search of the literature and selection of papers may be subject to human error. We are unable to consider whether there were other distractions accompanying family meals, such as television viewing.Citation43 Finally, the lack of homogeneity both in how the outcomes are measured and how family meals are measured precluded doing a more rigorous meta-analysis. Nonetheless, this review provides a useful overview of the state of the literature, and clearly identifies the gaps both in terms of methods used and outcomes that are not considered or rarely considered. Given the importance of identifying factors that are truly protective for adolescents, further research is called for to address these gaps.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ResnickMDBearmanPSBlumRWProtecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent HealthJAMA1997278108238329293990

- GibbsNMirandaCAThe magic of the family mealTime200616724505616792212

- HoffmanJThe guilt-trip casserole: the family dinner2009 Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/04/fashion/04dinner.htmlAccessed September 24, 2013

- Council of Economic AdvisersTeens and their parents in the 21st century: an examination of trends in teen behavior and the role of parental involvement2000 Available from: http://clinton3.nara.gov/WH/EOP/CEA/html/Teens_Paper_Final.pdfAccessed September 23, 2013

- EisenbergMEOlsonRENeumark-SztainerDStoryMBearingerLHCorrelations between family meals and psychosocial well-being among adolescentsArch Pediatr Adolesc Med2004158879279615289253

- FulkersonJAKubikMYStoryMLytleLArcanCAre there nutritional and other benefits associated with family meals among at-risk youth?J Adolesc Health200945438939519766944

- FulkersonJAStoryMMellinALeffertNNeumark-SztainerDFrenchSAFamily dinner meal frequency and adolescent development: relationships with developmental assets and high-risk behaviorsJ Adolesc Health200639333734516919794

- MusickKMeierAAssessing causality and persistence in associations between family dinners and adolescent well-beingJ Marriage Fam201274347649323794750

- EisenbergMENeumark-SztainerDFulkersonJAStoryMFamily meals and substance use: is there a long-term protective association?J Adolesc Health200843215115618639788

- SenBThe relationship between frequency of family dinner and adolescent problem behaviors after adjusting for other family characteristicsJ Adolesc201033118719619476994

- National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia UniversityThe importance of family dinners VIII: a CASAColumbia white paper2012 Available from: http://www.casacolumbia.org/upload/2012/2012924familydinnersVIII.pdfAccessed September 23, 2013

- FisherLBMilesIWAustinSBCamargoCAJrColditzGAPredictors of initiation of alcohol use among US adolescents: findings from a prospective cohort studyArch Pediatr Adolesc Med20071611095996617909139

- GriffinKWBotvinGJScheierLMDiazTMillerNLParenting practices as predictors of substance use, delinquency, and aggression among urban minority youth: Moderating effects of family structure and genderPsychol Addict Behav200014217418410860116

- FieseBHFoleyKPSpagnolaMRoutine and ritual elements in family mealtimes: contexts for child well-being and family identityNew Dir Child Adolesc Dev20062006111678916646500

- OchsEShohetMThe cultural structuring of mealtime socializationNew Dir Child Adolesc Dev2006111354916646498

- Neumark-SztainerDHannanPJStoryMCrollJPerryCFamily meal patterns: associations with sociodemographic characteristics and improved dietary intake among adolescentsJ Am Diet Assoc2003103331732212616252

- BerkLEInfantsChildrenAdolescents6th edBostonAllyn and Bacon2008

- MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJAltmanDGGroupPPreferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statementPLoS Med200967e100009719621072

- VarneySFrench lessons: why letting kids drink at home isn’t ‘tres bien.’2011 Available from: http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2011/12/12/143521104/french-lessons-why-letting-kids-drink-at-home-isn-t-tres-bienAccessed October 31, 2013

- CohenJA coefficient of agreement for nominal scalesEduc Psychol Meas19602013746

- VieraAJGarrettJMUnderstanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statisticFam Med200537536036315883903

- GraphPad SoftwareQuickCalcs2013 Available from: http://graphpad.com/quickcalcs/kappa1Accessed October 31, 2013

- FrankoDLThompsonDAffenitoSGBartonBAStriegel-MooreRHWhat mediates the relationship between family meals and adolescent health issuesHealth Psychol200827Suppl 2S109S11718377152

- GriffinKWBotvinGJScheierLMDiazTMillerNLParenting practices as predictors of substance use, delinquency, and aggression among urban minority youth: moderating effects of family structure and genderPsychol Addict Behav200014217418410860116

- HoffmannJPWarnickEDo family dinners reduce the risk for early adolescent substance use? A propensity score analysisJ Health Soc Behav201354333535223956358

- OfferSAssessing the relationship between family mealtime communication and adolescent emotional well-being using the experience sampling methodJ Adolesc201336357758523601623

- OfferSFamily time activities and adolescents’ emotional well-beingJ Marriage Fam20137512641

- PearsonJMullerCFriscoMLParental involvement, family structure, and adolescent sexual decision makingSociol Perspect20064916790

- FulkersonJAStraussJNeumark-SztainerDStoryMBoutelleKCorrelates of psychosocial well-being among overweight adolescents: the role of the familyJ Consult Clin Psychol200775118118617295578

- HeckmanJJEconometric causalityInt Stat Rev2008761127

- AntonakisJBendahanSJacquartPLaliveROn making causal claims: a review and recommendationsLeadersh Q201021610861120

- GeronimusATKorenmanSThe socioeconomic consequences of teen childbearing reconsideredQ J Econ1992107411871214

- NewhouseJPMcClellanMEconometrics in outcomes research: the use of instrumental variablesAnnu Rev Public Health199819117349611610

- MartinRMPatelRKramerMSEffects of promoting longer-term and exclusive breastfeeding on adiposity and insulin-like growth factor-I at age 11.5 years: a randomized trialJAMA2013309101005101323483175

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionE-cigarette use more than doubles among US middle and high school students from 2011–2012 [press release]AtlantaCDC2013 [September 5]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2013/p0905-ecigarette-use.htmlAccessed September 25, 2013

- GoniewiczMLZielinska-DanchWElectronic cigarette use among teenagers and young adults in PolandPediatrics20121304e879e88522987874

- ChoiKForsterJCharacteristics associated with awareness, perceptions, and use of electronic nicotine delivery systems among young US Midwestern adultsAm J Public Health2013103355656123327246

- PearsonJLRichardsonANiauraRSValloneDMAbramsDBe-Cigarette awareness, use, and harm perceptions in US adultsAm J Public Health201210291758176622813087

- SenBPatidarNThomasSA silver lining to higher prices at the pump? Gasoline prices and teen driving behaviorsAm J Health Promot Epub4262013

- CarpenterCSStehrMThe effects of mandatory seatbelt laws on seatbelt use, motor vehicle fatalities, and crash-related injuries among youthsJ Health Econ200827364266218242744

- WilliamsAWellsJLundASeat Belt Use among High School StudentsWashingtonNational Highway Traffic Safety Administration1982

- National Highway Traffic Safety AdministrationTraffic Safety Facts 2008WashingtonUS Department of Transportation2008

- EisenbergMENeumark-SztainerDFeldmanSDoes TV viewing during family meals make a difference in adolescent substance use?Prev Med200948658558719371761