Abstract

Purpose

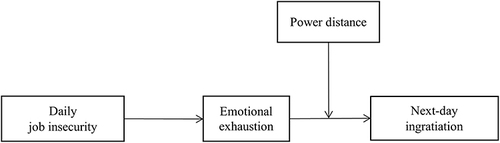

Numerous empirical studies consistently support the detrimental impact of job insecurity (JI) on employees. However, a new perspective suggests that individuals perceiving JI may proactively take measures to protect their positions. Drawing from the conservation of resources theory, this study argues that perceived resource loss due to JI motivates employees to engage in ingratiating behaviors for expanding their social capital. Additionally, this study empirically establishes the mediating role of emotional exhaustion and the moderating effect of power distance.

Methods

A daily diary design was used to examine the relationship between daily JI and next-day ingratiation. Our analyses of data collected from 134 full‐time employees across 10 consecutive working days using multi-level model.

Results

Our results showed that daily JI was found to affect next-day ingratiation (γ = 0.14, p < 0.01), and this relationship was mediated by emotional exhaustion (indirect effect = 0.07, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.01, 0.13]). Power distance moderated the relationship between emotional exhaustion and ingratiation (γ = 0.25, p < 0.001), and further moderated the indirect effect of JI on ingratiation via emotional exhaustion.

Conclusion

Our study has revealed that JI serves as a catalyst for employees to engage in resource creation behavior, thereby contributing to a deeper understanding of the implications of JI as an independent variable for both scholars and businesses.

Introduction

Job insecurity (JI) concerns a perceived threat to the continuity of employment as it is currently experienced.Citation1 The advancement of technology and the globalization of markets have undeniably yielded numerous advantages for the general public; however, they have concurrently imposed heightened expectations on employees.Citation2 Simultaneously, the emergence of artificial intelligence has facilitated the potential replacement of various conventional occupations. Unsurprisingly, the issue of JI has garnered increasing scholarly and public attention. Given its inevitable presence to some extent, it is imperative to comprehend the potential consequences associated with this phenomenon. Such understanding will enhance scholars’ comprehension of JI while aiding enterprises in recognizing its detrimental effects.

In previous research, JI has predominantly been viewed as a detrimental stressor with numerous adverse consequences for employees. However, the specific behaviors that continue to be influenced by JI remain an unresolved inquiry.Citation3 For instance, prior research has demonstrated that JI can influence negative behaviors such as retaliatory conduct and counterproductive work behavior, while also diminishing positive behaviors like job performance and organizational citizenship behavior.Citation4 On the other hand, some studies describe employees who perceive JI as “proactive actors”,Citation3 who may work hard to prove their importance in the organization, try to improve their relationships with superiors, and even compete with colleagues to keep their jobs. Simultaneously, employees perceiving JI are motivated to exhibit exemplary work behavior and minimize absenteeism.Citation5,Citation6 The available evidence suggests that the perception of JI can serve as a motivating factor for employees to proactively engage in actions aimed at securing their employment.

At the same time, the conservation of resources (COR) theory posits that individuals have a tendency to preserve and acquire their own resources.Citation7 Work is the primary source of income for individuals and is crucially important. From the perspective of COR theory, JI represents a state where a resource is about to be lost, and individuals will strive to maintain and defend their resources while also seeking ways to create more resources in order to avoid entering a “loss spiral”.Citation8 Based on the aforementioned considerations, we assert that employees’ aspiration for resources constitutes a pivotal determinant influencing their own behavioral patterns. In order to counteract JI and mitigate further resource depletion, employees resort to ingratiation as a means of expanding their work-related resources.

Following an examination of the association between JI and ingratiation, our research endeavors to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and boundary conditions governing this relationship. Primarily, JI acts as a detrimental stressor that depletes individuals’ resources, particularly their emotional reserves. Emotional exhaustion represents a crucial facet of job burnout, denoting a state characterized by the depletion of emotional and physiological resources.Citation9 Consequently, it is reasonable to posit that the perception of resource loss resulting from JI will heighten employees’ levels of emotional exhaustion. On the other hand, employees experiencing emotional exhaustion may proactively engage in preventive measures to mitigate further resource loss and seek to generate new resources.Citation10 In this context, ingratiation serves as a cost-effective strategy for resource craft, requiring employees to exhibit specific verbal expressions and actions aimed at gaining favor from both leaders and colleagues. The acquisition of such favor holds significant value as a social resource for employees. Thus, we posit that emotional exhaustion plays a crucial mediating role in transmitting the impact of JI on ingratiating behavior.

In addition, we posit that the impact of emotional exhaustion on ingratiation is contingent upon individual differences rather than being universally applicable. It is plausible that individuals with diverse cultural values exhibit varying levels of sensitivity towards this detrimental stressor, consequently leading to disparate psychological perceptions.Citation11 Power distance, as a significant cultural value orientation, signifies the extent to which individuals embrace disparities in power distribution within a society or organization. The higher the power distance, the stronger an individual’s acceptance of unequal power distribution.Citation12 Therefore, individuals with a high power distance will acknowledge the leader’s elevated status and naturally adopt a strategy of ingratiation as an additional resource upon perceiving emotional exhaustion. Conversely, individuals with a low power distance do not recognize the authority and high status of leaders, and even when they perceive inadequate resources, they will not embrace a strategy of ingratiation that contradicts their own volition. Hence, we hypothesize that power distance serves as a crucial boundary condition moderating the impact of emotional exhaustion on ingratiation.

Although numerous studies have been conducted to explore the consequences of JI, most of them primarily focus on its negative outcomes, suggesting that JI can have detrimental effects on both organizations and employees.Citation4 However, this study posits that individuals who experience JI may not necessarily become demoralized or retaliate against their organization; instead, they might strive to retain their jobs.Citation3 Furthermore, previous research tends to treat job insecurity as a relatively stable variable and investigates its long-term impact on emotions or behaviors. In contrast, the objective of this study is to examine the influence of short-term job insecurity on daily work behaviors. The work presented here makes three specific novel contributions to the literature. First, the daily diary method was employed to explore the relationship between daily JI and next-day ingratiation. Relevant research has seldom delved into the daily manifestation of JI and ingratiation.Citation3 A daily diary-based design is useful not only to capture the dynamic changes of JI and ingratiation, but also to indicate the direction of JI-ingratiation relationships. Second, we investigated the specific mechanism by which JI influences employee ingratiation, specifically examining the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Drawing upon COR theory, we posit that the scarcity of resources resulting from JI plays a pivotal role in driving employees to engage in ingratiating behaviors. Therefore, we selected emotional exhaustion as a variable representing employees’ state of resource scarcity and measured it separately from the independent and dependent variables to ascertain its mediating effect within this process. Third, despite the extensive research on power distance and workplace behavior, there has been a relative neglect in investigating how power distance influences employees’ coping strategies following their perception of JI. This study incorporates power distance as a between-individual variable to potentially moderate the relationship between JI and ingratiation. By doing so, this research contributes to the existing body of knowledge on power distance within the workplace and explores its potential role as an effective boundary condition for determining resource crafting behaviors.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Daily JI and Next-Day Ingratiation

We explore the consequences of daily JI because it possesses dynamism, which can be discussed from two perspectives. Firstly, for this study, Shoss’ (2017) definition of JI as “a perceived threat to the continuity and stability of employment as it is currently experienced” (p. 4) was adopted.Citation1 This definition underscores the subjective nature of JI, distinct from the actual risk of unemployment or objective depletion of job resources.Citation13 Consequently, this suggests that JI will not remain stable in the long term.Citation14

Secondly, empirical research indicates that JI can be influenced by immediate factors. For instance, the negative behaviors exhibited by leaders have been found to impact employees’ levels of JI,Citation15 Additionally, studies have demonstrated a link between negative affect and employees’ perceptions of JI.Citation16 Based on these empirical investigations, Schreurs et al observed that employees’ perception of JI exhibits weekly fluctuations.Citation17 Furthermore, Garrido Vásquez et al demonstrated that daily workplace events can induce fluctuations in employees’ perception of JI.Citation14 They also found that 23% of the observed variance in JI was attributable to individual differences, underscoring the significance of investigating JI within studies employing within-person designs.

COR theory focuses on the acquisition, management, and response to resources by individuals, encompassing conditions (such as employment) and energy (such as effort).Citation7,Citation18 Previous research has predominantly examined the emotional experiences following resource loss but has given limited attention to post-loss behaviors. According to COR theory, in situations where resources are depleted, acquiring new resources becomes increasingly vital. Individuals tend to invest their remaining resources in order to obtain fresh ones, facilitating a swift recovery from resource loss.Citation19 These findings suggest that individuals engage in resource creation behaviors in response to unemployment threats while mitigating its impact. Shoss et al revealed that JI stimulates individuals’ motivation for work retention.Citation3

The concept of ingratiation was advanced to describe an impression management strategy taken by employees to improve their image and status in the eyes of others.Citation20 Specifically, employees can acquire crucial resources, such as enhanced leader-subordinate exchange relationships, elevated social status, and increased opportunities for career progression through the mere act of expressing complimentary remarks or benevolent words.Citation21 Employees who engage in ingratiation behavior may be seeking to obtain significant benefits through these seemingly simple means. Thus, the primary purpose of ingratiation may have been to secure resource advantages rather than for impression management. Based on the aforementioned inference, we have grounds to posit that the perception of resource depletion induced by JI will prompt employees to engage in ingratiation behaviors as a means of replenishing their resources.

The study employed a daily diary method to investigate the relationship between JI and ingratiation behavior by matching each day’s JI with the subsequent day’s ingratiation behavior, thereby separating the measurement time of independent and dependent variables for each individual. This approach not only facilitates capturing daily ingratiation behaviors and mitigating recall bias,Citation22 but also enhances the ability to elucidate the directionality of the relationship between JI and employee ingratiation. We thus hypothesized the following:

H1: Daily JI is positively related to next-day employee ingratiation.

The Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion

According to the COR theory, JI leads to the depletion of individual resources, thereby prompting individuals to engage in more ingratiation behaviors. Therefore, it is crucial to have an indicator that can effectively represent the state of resource depletion in individuals. Emotional exhaustion refers to a state of fatigue that occurs after excessive utilization of psychological and emotional resources and is a stress reaction caused by workplace stressors.Citation23 Emotional exhaustion is a facet of job burnout, encompassing the state of depletion and fatigue in emotional and physiological resources, leading to a sense of personal depletion in emotional and related physiological reserves.Citation24 Previous research has established the association between emotional exhaustion and JI. For instance, Zhang et al revealed that JI influences employees’ experience of emotional exhaustion through their engagement in emotional labor.Citation9 Drawing on social exchange theory, Piccoli and De Witte (2015) examined the link between JI and emotional exhaustion.Citation25 Nauman et al discovered that JI impacts work-family conflict by means of its effect on emotional exhaustion.Citation26 As a crucial element of job burnout, emotional exhaustion refers to the state in which individuals deplete their emotional resources. These resources encompass the positive emotions necessary for maintaining employees’ well-being, known as vitality-based emotional resources.Citation27 The alteration in emotional resources, such as an escalation in anger and a decline in joy, contributes to the experience of emotional exhaustion. Simultaneously, JI originates from employees’ subjective perception and inevitably leads to a depletion of their emotional resources. In line with the COR theory, it is posited that perceiving JI as a threat to personal resources can deplete employees’ energy reserves, resulting in the experience of negative emotions and emotional exhaustion.Citation25 Consequently, it can be inferred that JI acts as a detrimental stressor leading to emotional exhaustion among employees.

Emotional exhaustion is perceived by employees as a depletion of available resources. According to the COR theory, when employees perceive scarcity in their resource pool, they will actively strive to acquire or generate additional resources in order to alleviate the state of resource loss and replenish their cognitive and energetic reserves.Citation7 For instance, Breevaart & Tims (2019) observed that daily experiences of emotional exhaustion prompt employees to strategically develop social resources.Citation19 The overwhelming body of research indicates that ingratiation confers benefits upon employees. For example, Koopman et al demonstrated that employees who engage in ingratiation behaviors are able to cultivate high-quality leader-member exchange, consequently increasing the likelihood of fair treatment by their supervisors.Citation28 Kim et al founded that employees who exhibit more ingratiating behavior than their colleagues have better social exchange quality with their supervisors.Citation29 Therefore, for employees, engaging in ingratiation represents a highly cost-effective strategy for resource creation. By seeking recognition from both superiors and colleagues and fostering positive social relationships through simple verbal expressions and actions, employees can effectively replenish their depleted social resources when experiencing emotional exhaustion.

In summary, this study concludes that perceiving JI leads to increased emotional exhaustion and resource scarcity among employees. To address these challenges, employees adopt various strategies to supplement existing resources and generate new ones, thereby promoting ingratiation. We thus hypothesized the following:

H2: Daily emotional exhaustion mediates the relationship of daily JI with next-day ingratiation.

The Moderating Role of Power Distance

After investigating the mediating role of emotional exhaustion, we further explore the boundary conditions of how JI influences ingratiation through emotional exhaustion. Power distance is an individual’s acceptance level of unequal power distribution in institutions and organizations,Citation30 which serves as a moderating variable influencing leader-subordinate behavior.Citation31 Individuals with high power distance readily accept the unequal distribution of power and perceive power disparities as inherent and anticipated, whereas individuals with low power distance exhibit a greater concern for the equitable allocation of power and are intolerant towards instances of unfair treatment.Citation32 This indicates that despite individuals experiencing comparable levels of emotional exhaustion and encountering resource scarcity, their behaviors may diverge due to variances in power distance.

Specifically, individuals with a high power distance orientation acknowledge the distinction between themselves and their leaders, perceiving ingratiation as an anticipated norm. Consequently, following experiences of emotional exhaustion, they are more inclined to naturally adopt this approach for resource generation. Conversely, individuals with a low power distance orientation perceive equality between leaders and subordinates without any discernible disparities in power or status.Citation12 The conflict between ingratiating behavior and their individual values will lead to the rejection of this resource-creating behavior, even in situations involving potential loss of resources. Considering a moderating effect of power distance together with the indirect effect from Hypothesis 2, we posit that indirect effects from daily JI to next-day ingratiation via emotional exhaustion will be especially strong for individuals with high levels of power distance.

H3: Power distance moderates the relationship between daily JI and ingratiation such that this relationship is stronger for high-power distance individuals than for low-power distance individuals.

H4: Power distance moderates the indirect effect in Hypothesis 2 such that it is stronger for high- power distance individuals than for low-power distance individuals.

A theoretical model encompassing the presently hypothesized relationships is presented in .

Method

Participants

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Academic Board of East China Normal University (HR1-1060-2020) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. We collected data from a total of 160 participants recruited through word-of-mouth and research recruitment ads in China. These recruitment methods, which have been used successfully in prior diary-based research,Citation33 enabled a diverse pool of potential participants to be contacted. Since our daily diary method requires collecting employee data at a fixed time to measure their daily work behavior, we need to exclude night shift workers. Additionally, considering the adaptation period for new employees, they will also be excluded. The inclusion criteria were being 18 years or older, working full-time during normal business hours (ie, not working night shifts), and having a work history of at least 3 months in one’s current jobs. We invited potential participants to read a consent letter that provides complete information about the study, after which they could decide to participate or not. The informed consent form was signed by each participant prior to the commencement of the study.

Twenty-six participants did not have at least three observation days and were therefore excluded. Thus, the final study sample consisted of 134 participants, of which 55 (41.0%) were female. The cohort had a mean age (±standard deviation, SD) of 37.13 (±9.85) years and a mean organizational tenure of 15.09 (±11.23) years. Participants each received 35 yuan in compensation.

Procedure

Data were collected in two phases. In the first phase, participants completed a baseline survey that included questions about demographics and power distance. Commencing a week later, in the second phase, participants completed twice-daily surveys for 10 working days (ie, Monday-Friday for two weeks). We adopted an interval-contingent design such that there was a specific time window during which participants were expected to complete their daily surveys.Citation34 The research team sent out an Email at 7:00 a.m. with a link to the morning survey, which consisted of questions about participants’ emotional exhaustion the night before, and asked participants to complete the survey within the next three hours. Those who had not completed the survey received a 9:00 a.m. reminder. The morning survey was closed at 10:00 a.m. At 5:00 p.m., participants received their evening survey email, which asked them to complete that survey after work. The evening survey consisted of questions about JI, ingratiation, and workload during the workday. Around 8:00 p.m., a reminder was sent to those who had not completed the evening survey yet. The evening survey was closed at 11:00 p.m. All surveys were administered in Chinese. We followed Brislin’s (1980) translation-back translation procedure to ensure the accuracy of translation.Citation35

Our study hypotheses involve the independent variables of JI on day t, and the dependent variables of nighttime emotional exhaustion and ingratiation, surveyed on Day t + 1. Emotional exhaustion and ingratiation were also assessed on Day t to serve as control variables. Therefore, a complete daily observation required that the participant took both the morning and evening surveys on Day t and Day t + 1. We received 1037 of 1280 possible daily observations (160 people × 8 days), resulting in an overall participation rate of 81.02%.

Measures

All measurements are presented in Chinese, and participants answered all survey items on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Job insecurity (Day t evening survey)

Similar to Garrido Vásquez et al (2019),Citation14 we assessed daily JI with a single-item query “Today I have been worrying about the future of my job”.

Emotional exhaustion (Day t + 1 morning survey)

Emotional exhaustion was assessed in the Day t + 1 morning survey with a three-item scale produced by Watkins et alCitation36 An example item is “Last night, I feel emotionally drained from my work”. The mean Cronbach’s alpha value for this scale was 0.93 (±.01) (range = 0.91–0.95).

Ingratiation (Day t + 1 evening survey)

Ingratiation was assessed with a four-item scale developed by Ingold et al.Citation37 We adjusted the time frame so that the items referred specifically to the particular day. An example item is “Today, I have praised the idea of my supervisor/colleague”. The mean Cronbach’s alpha value for this scale was 0.92 (±.02) (range = 0.90–0.95).

Power distance (baseline survey)

Power distance is an individual’s acceptance level of unequal power distribution in institutions and organizations. Individuals with a high power distance believe that their superiors are superior to them and do not need to take the opinions of subordinates into account when making decisions.We assessed power distance in a baseline survey with a six-item measure developed by Dorfman and Howell (1988).Citation38 An example item is “Managers should make most decisions without consulting subordinates”. The Cronbach’s alpha value for this scale was 0.77.

Control variable

Given the established impact of workload on emotional exhaustion,Citation39 and the influence of positive emotions on employees’ daily workplace behavior,Citation40 we will incorporate workload and positive emotions as covariates in our model. We assessed daily workload (Day t evening survey) with a single-item query “Today, my workload is heavy”. At the same time, we measured positive affect (Day t + 1 morning survey) with the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS).Citation41 Participants rated their current experience of 10 emotions on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The mean Cronbach’s alpha value for this scale was 0.98 (±.01) (range = 0.96–0.98).

Analytic Strategy

Means, within-person SDs, and between-person SDs of the study variables were determined. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs), and inter-class (Pearson) correlations among the variables were calculated. Multilevel confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to examine the factor structure of study variables. These preliminary analyses were conducted in SPSS (IBM, USA).

We subjected our nested data to multilevel modeling in Mplus 8.6. Days (level 1) were nested within individuals (level 2). Three models were tested. In Model 1, we examined the effect of daily JI on next-day ingratiation while controlling for positive affect and prior-day ingratiation at level 1. In Model 2, we examined our mediation hypotheses by estimating the effect of JI on emotional exhaustion, while controlling for workload and prior-day emotional exhaustion, and analyzed the effect of exhaustion on next-day ingratiation while controlling for positive affect and prior-day ingratiation. In Model 3, we added level-2 power distance to the factors included in Model 2 and we specified the cross-level effect of power distance on the random slope between emotional exhaustion and ingratiation measurement results. To prevent the within-person level analyses from being confounded by between-person level relationships, within-person predictors were mean centered such that variable deviations were related to each individual’s own 2-week average. Between-person predictors were grand-mean centered. Model fitness was determined based on χ2, comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) values. Simple slope test results are reported as γ variables and indirect effect analysis results are reported as conditional indirect effect values with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In all cases, p < 0.05 was considered significant; otherwise, analysis results are indicated as not significant (n.s.).

Results

Preliminary Analysis

Descriptive statistics (means and SDs) and Pearson correlations among study variables are reported in . One-way analyses of variance showed that there were significant between-person variances in emotional exhaustion [(ICC1) = 0.62, F133, 903 = 13.85, p < 0.001] and ingratiation (ICC1 = 0.63, F133, 903 = 14.33, p < 0.001), thus supporting the use of multilevel modeling for incorporation of the nested nature of the data.Citation42,Citation43

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Study Variables

For our multilevel confirmatory factor analysis conducted to examine factor structure, we first fit the data to a four-factor (JI, emotional exhaustion, positive affect, and power distance) model, in which each item was loaded on its respective latent variable. This four‐factor model fitted well with our data [χ2 (340) = 943.85, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.04]. Subsequently, an alternative three-factor model wherein items from emotional exhaustion and positive affect were loaded on one latent variable was tested. This model provided a worse fit than the four-factor model [χ2 (345) = 1859.83, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.76, RMSEA = 0.07]. These results support maintaining a distinction among the daily constructs.

Hypothesis Testing

Our multilevel modeling results are reported in with unstandardized coefficients and standard errors. In Model 1, daily JI was found to affect next-day ingratiation (γ = 0.14, p < 0.01), thus supporting Hypothesis 1. In Model 2, daily JI affected emotional exhaustion (γ = 0.18, p < 0.001), emotional exhaustion affected next‐day ingratiation (γ = 0.12, p < 0.05), and an indirect effect of daily JI on next-day ingratiation via emotional exhaustion was observed (indirect effect = 0.07, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.01, 0.13]), thus supporting Hypothesis 2.

Table 2 Multilevel Modeling Results

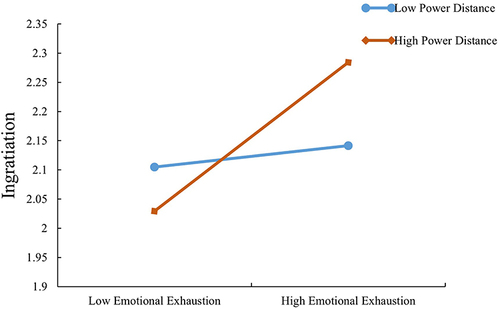

In Model 3, there was a significant interaction between emotional exhaustion and power distance (γ = 0.25, p < 0.001), indicating that power distance moderated the relationship between emotional exhaustion and ingratiation. The pattern () indicates that the positive relationship between emotional exhaustion and ingratiation was stronger in high-power distance participants than in low-power distance participants, thus supporting Hypothesis 3.

Figure 2 Moderating effect of power distance on the relationship between emotional exhaustion and ingratiation.

Simple slope tests showed that the effect of emotional exhaustion on ingratiation was significant when power distance was high (γ = 0.30, p < 0.001) but not when power distance was low (γ = −0.02, n.s.). Further, a conditional indirect effect of daily JI, via emotional exhaustion, on next-day ingratiation was significant for high-power distance participants (conditional indirect effect = 0.09, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.02, 0.15]), but not for low-power distance participants (conditional indirect effect = −0.01, n.s., 95% CI [−.04, 0.03]). The difference between these indirect effects for the two power distance-tendency groups was significant (difference = 0.09, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.01, 0.17]). Thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Discussion

Theoretical and Practical Implications

Our two-week twice-daily survey suggests that JI as a subjective perception that can improve next-day ingratiation. As predicted, emotional exhaustion mediates this relationship. Our findings have important theoretical implications. Firstly, according to the COR theory, we posit that the experience of resource depletion resulting from JI will augment employees’ inclination towards ingratiating behavior, thereby enhancing our comprehension of this phenomenon. In the present study’s hypothesis, ingratiating behavior is conceptualized not only as an impression management strategy but also as a proactive means for resource craft. The experience of JI leading to resource depletion can engender a profound sense of crisis among employees, compelling them to proactively generate additional resources.Citation3 When individuals perceive uncertainty regarding their employment, they may employ various strategies aimed at safeguarding or replenishing their resources, such as seeking organizational or leadership support and expanding their interpersonal networks.Citation44 Ingratiating behavior encompasses deliberate attitudes and actions displayed by employees in order to align with others’ perspectives or preferences, thereby seeking favor or advantages—a social influence tactic.Citation29 Consequently, in an effort to secure their positions, employees are likely to exhibit heightened levels of ingratiating behaviors as a means of preserving their social capital.

Secondly, we have expanded the scope of outcome variables in our study on JI. Shoss et al has demonstrated that JI influences job preservation motivation and ingratiating behavior as a form of impression management, while providing an explanation based on COR theory.Citation3 Building upon this foundation, we specifically selected ingratiating behavior as a representative resource-crafting behavior to investigate whether individuals engage in such behavior after experiencing JI in order to expand their own resources, thereby further exploring its underlying mechanisms. Currently, the majority of studies examining JI and workplace behavior are cross-sectional in nature, potentially implying that an individual’s behavior is the cause rather than the consequence of JI.Citation3 To address this limitation, we conducted a daily diary study to investigate ingratiation dynamics at a micro level while maintaining ecological validity,Citation45 thereby overcoming challenges associated with capturing and manipulating ingratiation in controlled settings. Meanwhile, our assessment of the indirect and direct variables at different time points enables us to infer their causal direction to some extent. In addition, there is limited understanding regarding the strategies employees may employ to secure their positions. Drawing upon the COR theory, our findings indicate that individuals who have encountered JI tend to proactively engage in resource-crafting behaviors, thus necessitating further investigation in future research.

Thirdly, our findings demonstrate that emotional exhaustion serves as a mediator in the relationship between JI and ingratiation. Studies have been conducted to explore the relationship between JI and emotional exhaustion, which have confirmed a positive association between JI and emotional exhaustion.Citation25,Citation46 Recently, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, it has also been found that COVID-19-related JI is positively correlated with emotional exhaustion.Citation47 Our research findings are consistent with these studies. Additionally, we used a daily diary method to verify that daily JI can impact daily emotional exhaustion. This indicates that the influence of JI on exhaustion is not only formed through long-term accumulation but can also have immediate effects within a short period of time.

Fourthly, our results also revealing the moderating influence of power distance. This not only enhances our understanding of the specific mechanisms and boundary conditions through which JI impacts ingratiation but also provides partial validation for the impact of power distance on such behavior. Power distance is frequently employed as a moderating variable due to its reflection of individual values.Citation48 Individuals with lower power distance exhibit heightened sensitivity towards organizational justice and promptly respond with corresponding behaviors upon perceiving any degree of unfairness.Citation49 Our study reveals that an individual’s subsequent actions following perceived resource inadequacy are contingent upon their level of power distance. For individuals with high power distance, ingratiating may be a strategy they frequently employ in their daily lives. Therefore, in situations of resource scarcity, they will actively use ingratiation to expand their social resources. However, for individuals with low power distance, ingratiation represents lowering their status to cater to others, which is unacceptable to them. This study combines the framework of COR theory with power distance to explore why employees choose different strategies when creating resources, providing new directions for future research.

Simultaneously, this study holds practical significance as it reveals that employees with JI experience are inclined to perceive resource loss and proactively seek opportunities to expand their resources, which also entails a certain level of organizational responsibility. Therefore, organizations should prioritize the support and assistance provided to resource-poor employees by monitoring their behaviors for signs of anxiety stemming from resource scarcity. By facilitating the recovery and development of available resources, enterprises can enable employees to channel greater energy into their work, thereby contributing to overall enterprise growth.Citation50

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations exist in our study. Firstly, the utilization of self-reported variables in our analyses may introduce common method variance issues,Citation51 as individuals tend to respond to questions in a socially desirable manner.Citation45,Citation52 To address this concern, future research could consider incorporating multi-source data collection methods for obtaining more objective information.

Second, our daily diary-based design involved data collection of different variables at different timepoints. Although this approach had the benefit of enabling us to analyze a delayed effect of daily JI on next‐day ingratiation via emotional exhaustion and the results obtained via this approach can be strongly indicative of causal directionality, causal conclusions cannot be made. Future studies may verify the presently suggested causal relationship between daily JI and ingratiation by employing experimental methods that manipulate employees’ perceptions of JI and by exploring the consequent effects on ingratiation.

Third, further verification is needed regarding the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. JI can be influenced by various life events, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, which may render individuals more susceptible to experiencing emotional exhaustion. This necessitates considering additional control variables to determine whether the mediating effect of emotional exhaustion between JI and ingratiation remains stable Moreover, due to the volatility of emotional exhaustion, there may also exist other moderating variables that need further examination in future research on the impact of JI on emotional exhaustion.

Disclosure

We have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Shoss MK. Job insecurity: an integrative review and agenda for future research. J Manage. 2017;43(6):1911–1939. doi:10.1177/0149206317691574

- Lee S, Kim SL, Yun S. A moderated mediation model of the relationship between abusive supervision and knowledge sharing. Leadersh Q. 2018;29(3):403–413. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.09.001

- Shoss MK, Su S, Schlotzhauer AE, Carusone N. Working hard or hardly working? An examination of job preservation responses to job insecurity. J Manage. 2022;01492063221107877. doi:10.1177/01492063221107877

- Chirumbolo A. The impact of job insecurity on counterproductive work behaviors: The moderating role of honesty–humility personality trait. J Psychol. 2015;149(6):554–569. doi:10.1080/00223980.2014.916250

- Hewlin PF, Kim SS, Song YH. Creating facades of conformity in the face of job insecurity: a study of consequences and conditions. J Occup Organ Psych. 2016;89(3):539–567. doi:10.1111/joop.12140

- Miraglia M, Johns G. Going to work ill: a meta-analysis of the correlates of presenteeism and a dual-path model. J Occup Health Psychol. 2016;21(3):261–283. doi:10.1037/ocp0000015

- Hobfoll SE, Halbesleben J, Neveu JP, Westman M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2018;5:103–128. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

- Jiang L, Xu X, Wang HJ. A resources–demands approach to sources of job insecurity: a multilevel meta-analytic investigation. J Occup Health Psychol. 2021;26(2):108–126. doi:10.1037/ocp0000267

- Zhang L, Lin Y, Zhang L. Job insecurity and emotional exhaustion: the mediating effects of emotional labor. J Manag Sci. 2013;26(3):1–8. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672-0334.2013.03.001

- He Y, Yu J. The effect of electronic communication during non-work time on employees’ time banditry behavior: a conservation of resources theory perspective. Hum Resour Dev China. 2020;37(1):54–67. doi:10.16471/j.cnki.11-2822/c.2020.1.004

- Zheng X, Liu X. The effect of interactional justice on employee well-being: the mediating role of psychological empowerment and the moderating role of power distance. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2016;48(6):693. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2016.00693

- Zhong L, Meng J, Gao L. Ethical leadership and employee creative performance: the mediating role of social exchange and the moderating role of power distance orientation. J Manag World. 2019;35(5):149–160. doi:10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2019.0072

- Sverke M, Hellgren J, Näswall K. No security: a meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. J Occup Health Psychol. 2002;7(3):242. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.7.3.242

- Garrido Vásquez ME, Kälin W, Otto K, Sadlowski J, Kottwitz MU. Do co‐worker conflicts enhance daily worries about job insecurity: a diary study. Appl Psychol. 2019;68(1):26–52. doi:10.1111/apps.12157

- Wang D, Li X, Zhou M, Maguire P, Zong Z, Hu Y. Effects of abusive supervision on employees’ innovative behavior: the role of job insecurity and locus of control. Scand J Psychol. 2019;60(2):152–159. doi:10.1111/sjop.12510

- Debus ME, König CJ, Kleinmann M. The building blocks of job insecurity: the impact of environmental and person-related variables on job insecurity perceptions. J Occup Organ Psych. 2014;87(2):329–351. doi:10.1111/joop.12049

- Schreurs BH, van Emmerik IJ H, Günter H, Germeys F. A weekly diary study on the buffering role of social support in the relationship between job insecurity and employee performance. Hum Resour Manage. 2012;51(2):259–279. doi:10.1002/hrm.21465

- Duan J, Yang J, Zhu Y. Conservation of resources theory: content, theoretical comparisons and prospects. Psychol Res. 2020;13(1):49–57.

- Breevaart K, Tims M. Crafting social resources on days when you are emotionally exhausted: the role of job insecurity. J Occup Organ Psych. 2019;92(4):806–824. doi:10.1111/joop.12261

- Liu C, Ke X, Liu J, Wang Y. The scene selection of the upwards ingratiation by the employees: an indigenous research. Nankai Bus Rev. 2015;18(5):54–64.

- Sibunruang H, Garcia PRJM, Tolentino LR. Ingratiation as an adapting strategy: its relationship with career adaptability, career sponsorship, and promotability. J Vocat Behav. 2016;92:135–144. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2015.11.011

- Schwarz N, Sudman S Autobiographical Memory and the Validity of Retrospective Reports. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012.

- Barling J, Macintyre AT. Daily work role stressors, mood and emotional exhaustion. Work Stress. 1993;7(4):315–325. doi:10.1080/02678379308257071

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):397–422. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

- Piccoli B, De Witte H. Job insecurity and emotional exhaustion: Testing psychological contract breach versus distributive injustice as indicators of lack of reciprocity. Work Stress. 2015;29(3):246–263. doi:10.1080/02678373.2015.1075624

- Nauman S, Zheng C, Naseer S. Job insecurity and work–family conflict: a moderated mediation model of perceived organizational justice, emotional exhaustion and work withdrawal. Int J Confl Manage. 2020;31(5):729–751. doi:10.1108/IJCMA-09-2019-0159

- Ito JK, Brotheridge CM. Resources, coping strategies, and emotional exhaustion: a conservation of resources perspective. J Vocat Behav. 2003;63(3):490–509. doi:10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00033-7

- Koopman J, Matta FK, Scott BA, Conlon DE. Ingratiation and popularity as antecedents of justice: a social exchange and social capital perspective. Organ Behav Hum Decis Pro. 2015;131:132–148. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2015.09.001

- Kim Y, Kramer A, Pak S. Job insecurity and subjective sleep quality: The role of spillover and gender. Stress Health. 2021;37(1):72–92. doi:10.1002/smi.2974

- Khatri N. Consequences of power distance orientation in organisations. Vision. 2009;13(1):1–9. doi:10.1177/097226290901300101

- Mao C, Guo L. Power distance orientation in organization and management research: concept, measurement, and outcomes. Hum Resour Dev China. 2020;1:21–34. doi:10.16471/j.cnki.11-2822/c.2020.1.002

- Liu C, Yang LQ, Nauta MM. Examining the mediating effect of supervisor conflict on procedural injustice–job strain relations: the function of power distance. J Occup Health Psychol. 2013;18(1):64–74. doi:10.1037/a0030889

- Butts MM, Becker WJ, Boswell WR. Hot buttons and time sinks: The effects of electronic communication during nonwork time on emotions and work-nonwork conflict. Acad Manage J. 2015;58(3):763–788. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.0170

- Fisher CD, To ML. Using experience sampling methodology in organizational behavior. J Organ Behav. 2012;33(7):865–877. doi:10.1002/job.1803

- Brislin RW. Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In: Triandis HC, Berry JW, editors. Handbook of Crosscultural Psychology. Vol. 2. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1980:349–444.

- Watkins MB, Ren R, Umphress EE, Boswell WR, Del C TM, Zardkoohi A. Compassion organizing: employees’ satisfaction with corporate philanthropic disaster response and reduced job strain. J Occup Organ Psych. 2015;88(2):436–458. doi:10.1111/joop.12088

- Ingold PV, Kleinmann M, König CJ, Melchers KG. Transparency of assessment Centers: lower criterion-related validity but greater opportunity to perform? Pers Psychol. 2016;69(2):467–497. doi:10.1111/peps.12105

- Dorfman PW, Howell JP. Dimensions of National Culture and Effective Leadership Patterns: Hofstede Revisited. Vol. 3. Greenwich, CT: JAI press; 1988.

- Baeriswyl S, Krause A, Elfering A, Berset M. How workload and coworker support relate to emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of sickness presenteeism. Int J Stress Manag. 2017;24(S1):52–73. doi:10.1037/str0000018

- Fritz C, Sonnentag S. Antecedents of day-level proactive behavior: a look at job stressors and positive affect during the workday†. J Manage. 2009;35(1):94–111. doi:10.1177/0149206307308911

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

- Bartko JJ. On various intraclass correlation reliability coefficients. Psychol Bull. 1976;83(5):762–765. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.83.5.762

- James LR. Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement. J Appl Psychol. 1982;67(2):219–229. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.67.2.219

- Klehe UC, Zikic J, van Vianen AE, Koen J, Buyken M. Coping proactively with economic stress: Career adaptability in the face of job insecurity, job loss, unemployment, and underemployment. In: The Role of the Economic Crisis on Occupational Stress and Well Being. Vol. 10. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2012:131–176.

- Cangiano F, Parker SK, Yeo GB. Does daily proactivity affect well-being? The moderating role of punitive supervision. J Organ Behav. 2019;40(1):59–72. doi:10.1002/job.2321

- Kerse G, Koçak D, Özdemir Ş. Does the perception of job insecurity bring emotional exhaustion? The relationship between job insecurity, affective commitment and emotional exhaustion. Busi Eco Res J. 2018;9(3):651–663. doi:10.20409/berj.2018.129

- Khan AK, Khalid M, Abbas N, Khalid S. COVID-19-related job insecurity and employees’ behavioral outcomes: mediating role of emotional exhaustion and moderating role of symmetrical internal communication. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2022;34(7):2496–2515. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-05-2021-0639

- Lin W, Wang L, Chen S. Abusive Supervision and Employee Well-Being: The Moderating Effect of Power Distance Orientation. Appl Psychol Int Rev. 2013;62(2):308–329. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00520.x

- Park HS, Hoobler JM, Wu J, Hu J, Wilson M. Abusive supervision, justice, power distance, and employee deviance: a meta-analysis. Acad Manage Proceed. 2015;vol2015:12462. doi:10.5465/ambpp.2015.73

- Alnaimi AMM, Rjoub H. Perceived organizational support, psychological entitlement, and extra-role behavior: The mediating role of knowledge hiding behavior. J Manag Organ. 2021;27(3):507–522. doi:10.1017/jmo.2019.1

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Wehrt W, Casper A, Sonnentag S. Beyond depletion: Daily self‐control motivation as an explanation of self‐control failure at work. J Organ Behav. 2020;41(9):931–947.