Abstract

Background

Intergenerational solidarity between parents and emerging adult offspring requires more substantial attention at the present time. Changing demographic structures and transformations in family dynamics over recent decades have increased both opportunities and the need for parent-child interactions and exchanges of support and affection during emerging adulthood.

Purpose

The study had two aims: first, to explore patterns in intergenerational solidarity in accordance with different sociodemographic characteristics of emerging adults; and second, to analyse associations between intergenerational solidarity and emerging adults’ psychological distress and satisfaction with life.

Methods

Participants were 644 emerging adult university students from Southern Europe (Spain and Portugal), aged between 18 and 29 years, who completed a self-report questionnaire designed to assess variables linked to sociodemographic aspects (gender, country of residence, sexual orientation, living status, family income), intergenerational solidarity, psychological distress and satisfaction with life.

Results

The results indicated some differences in intergenerational solidarity patterns in accordance with a range of sociodemographic characteristics. They also revealed significant associations between intergenerational solidarity dimensions and emerging adults’ satisfaction with life and psychological distress. Moreover, affective solidarity was found to fully mediate the relationship between associational, functional and normative solidarity and emerging adults’ adjustment. In the case of conflictual solidarity, affective solidarity was found to partially mediate the relationship between this dimension of intergenerational solidarity and emerging adults’ distress and to fully mediate the relationship between this same dimension and emerging adults’ satisfaction with life.

Conclusion

The results indicate that it is important to take sociodemographic diversity into account when exploring relationships between emerging adults and their parents. They also suggest that affective solidarity acts as a protective factor in promoting emerging adults’ adjustment.

Introduction

Interest in intergenerational relationships, in particular intergenerational family solidarity between parents and their adult children, is increasing.Citation1,Citation2 This is largely due to the significant changes in economic, cultural and demographic trends that have occurred in Western post-industrial societies over recent years. These changes have a considerable impact, amongst others, on young people’s lives, the dynamics of their relationships with their parents and the interactions that take place between them. In general, these changes have increased the level and duration of young people’s dependency on their parents, particularly in countries such as Spain and Portugal.Citation3

One major consequence of the aforementioned changes is a delay in young people’s transition to typical adult roles, a circumstance that has given rise to a new developmental stage known as emerging adulthood (18 to 29 years). Emerging adulthood is a period defined by many characteristics of the sociocultural context, but, in general, is associated with identity exploration, instability in love, work and place of residence, and a wide range of choices and possibilities about the future.Citation4 During this new period, emerging adults try to invest in gaining educational qualifications in order to find a job and establish themselves in an increasingly competitive and highly-skilled labour market, often characterised by high unemployment rates among this age group. In Spain, university students represent 32.3% of all young people aged between 18 and 24 years.Citation5 In Portugal, in 2022, 47.5% of young people aged between 24 and 30 held a university degree.Citation6 Despite a sustained increase in academic qualifications in both countries, however, the unemployment rate in 2021 for those aged between 20 and 24 years was around 32% and 22% in Spain and Portugal, respectively.Citation7 Consequently, most emerging adults do not have enough stability to afford independent housing, and postpone leaving the parental home or live in a state of semi-autonomy, an intermediate living arrangement half way between co-residence with parents and full residential independence. According to the latest data from 2021, the mean age at which young people left the parental home was 28.9 and 33.6 years in Spain and Portugal, respectively.Citation8 Moving out of the parental home later means that at least two generations of adults often live under the same roof for a more prolonged period than in previous generations. It also means that marriage and parenthood are also delayed, with the mean age at first marriage being 37.2 and 34 years in Spain and Portugal, respectively, in 2021,Citation9 and the mean age for women at the birth of their first child being 32.6 and 31.8 years, in Spain and Portugal respectively, in that same year.Citation10

As a result of these changing demographic structures and family dynamics, both parents and their emerging adult offspring have more opportunities and an increased need for interaction, exchanges of support and affection, and mutual influence. The theoretical model of intergenerational solidarityCitation11 has been widely used in research to describe social cohesion and interactions between adult relatives from different generations. Within this framework, which was initially conceived for elderly people and their adult children, intergenerational solidarity is conceptualised as a multidimensional construct comprising behavioural and emotional dimensions of interaction, cohesion, affection and support between parents and adult children in the course of long-term relationships. The construct initially comprised six dimensions: affectual solidarity, referring to having positive feelings about family members; associational solidarity, referring to the type and frequency of contact between intergenerational family members; consensual solidarity, referring to agreement in opinions, values, and attitudes between generations; functional solidarity, referring to help and resources exchanged across generations; normative solidarity, or commitment regarding the performance of family roles and obligations; and finally, structural solidarity, or geographical proximity between family members.Citation11,Citation12 Because intergenerational solidarity is a construct open to revision, the model was later re-theorised to include conflictual solidarity as a new dimension reflecting a normal facet of family relationships, which differs from the absence of affection and does not usually jeopardise willingness to engage in the exchange of intergenerational support.Citation13

Research into intergenerational solidarity during emerging adulthood is still scarce. Very few studies have focused on emerging adults or have included this age range in their samples, and fewer still have striven to include sociodemographically diverse samples. Nonetheless, several sociodemographic aspects (eg, gender and socioeconomic status) seem to have an impact on intergenerational exchanges within the family system.Citation14 For example, it seems that women provide their parents with more help -functional solidarity-Citation15,Citation16 and emotional support - affective solidarity- than men.Citation15 Moreover, as expected, co-residing with parents is positively associated with face-to face and non-face-to face contact -associational solidarity-, support (financial or instrumental) -functional solidarity- and affective solidarity.Citation17 Regarding socioeconomic status (SES), the results are, in general, contradictory.Citation14 However, Timonen et alCitation18 found that, in general, intergenerational solidarity towards parents is particularly strong among young people from low and middle SES groups. Other studies focusing on diversity in terms of sexual orientation found that lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) emerging adults perceived lower levels of affective and normative solidarity and higher levels of conflictual solidarity than their heterosexual counterparts.Citation19

As the type of ties present in parent-child relationships differ across sociocultural contexts, this aspect is also relevant for understanding intergenerational solidarity within the family. Southern European countries are characterised by strong family ties, a persistence of close parent-child relationships, and offspring remaining in the parental home until later in life, usually until they have a stable job or long-term romantic relationship. Northern European countries and the United States of America, on the other hand, are characterised by weaker family ties and offspring leaving the parental home and gaining economic independence at a younger age.Citation20 Given this, it is hardly surprising that intergenerational care (by adult children of their parents) is higher in Southern than in Northern European countries, with people in Southern Europe perceiving and responding more to their family members’ need for supportCitation21 and reporting more frequent contact between family members.Citation22

Research also suggests that intergenerational solidarity (eg, parent-child closeness or family support) between family members contributes to children’s positive development throughout adolescence and adulthood.Citation23–25 However, here again, research has paid far less attention to the influence of intergenerational solidarity on the psychological development of emerging adult offspring. Some researchers have suggested that emerging adults who feel closer to and get along better with their parents have a better sense of mutual understanding with them, and perceptions of greater support from family (eg, emotional support, advice, help with decision making) have been associated with low levels of psychological distress (eg, depressive symptoms or loneliness).Citation26 Other authors found that high levels of family values and a strong sense of family obligation were associated with high levels of well-being among offspring.Citation27 Likewise, high levels of received, given and anticipated functional and normative solidarity have been linked to high levels of life satisfaction among that same group.Citation28 In a similar vein, another study found that affective, functional and associational solidarity were also related to life satisfaction during emerging adulthood.Citation17 Consequently, despite possible constraints regarding autonomy, intergenerational solidarity between parents and emerging adult children seems, in general, to have a positive impact on the healthy development of offspring during this life stage.

It should be noted that affection has traditionally been considered a key variable for understanding the relationships established between parents and adult childrenCitation29 and, specifically, affective solidarity has been repeatedly analysed alongside other family dimensions. In this sense, previous studies report that affective solidarity is associated with greater associational, functional and normative solidarity,Citation26 as well as with fewer situations of conflict among family members.Citation30 Likewise, some empirical studies have found that affective solidarity is associated with greater well-beingCitation17 and mediates the association between other intergenerational solidarity dimensions (eg, normative solidarity) and maladjustment.Citation26 It therefore seems that affective solidarity has positive implications in parent-child relationships and helps foster healthy psychological development among offspring.

The Present Study

The present study aimed to explore patterns in intergenerational solidarity in accordance with different sociodemographic characteristics among emerging adults from Southern Europe. Based on the results of previous research, we expected to find some differences in intergenerational solidarity in accordance with sociodemographic variables. However, no hypotheses were formulated regarding the nature of these differences due to the scarcity of studies carried out with sociodemographically diverse samples. The second aim of the study was to analyse associations between intergenerational solidarity and emerging adults’ psychological distress and satisfaction with life. We expected intergenerational solidarity to be negatively associated with psychological distress and positively associated with satisfaction with life. We also expected affective solidarity to mediate the relationship between the other intergenerational solidarity dimensions assessed (conflictual, associational, functional and normative solidarity) and emerging adults’ psychological distress and satisfaction with life.

The present study seeks, firstly, to contribute to the existing body of knowledge regarding intergenerational solidarity during emerging adulthood, since although this construct has been widely studied among older adults, very little research to date has focused on earlier stages of development. Emerging adulthood is a distinct developmental period with singular characteristics in which young people, who are mature in many aspects, continue to depend on their families and live in the parental home.Citation3 This new family situation necessitates a more in-depth examination of the processes that take place in it, one of which is intergenerational solidarity. The study also aims to help advance research into family relationships during emerging adulthood in Southern Europe. To date, most research focusing on the family environment during this life stage has been conducted in Northern European and North America, and since the nature of parent-child ties differs across sociocultural contexts,Citation20 there is a need to address the dynamics of interactions, cohesion and support within the family beyond the borders of these geographical regions. The present study therefore seeks to fill a gap in the extant literature by focusing on emerging adulthood in two Southern European countries, namely Spain and Portugal.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The total sample comprised 644 emerging adults (81.8% women) recruited from two universities in Spain (Universidad de Sevilla) and Portugal (Universidade do Porto). The Spanish sample comprised 318 emerging adults (77.7% women) and the Portuguese sample contained 326 (85.9% women). All Participants were recruited within the project Relações familiares em Portugal e ajustamento psicológico: investigação intercultural entre Espanha e Portugal (Family relations in Portugal and psychological adjustment: intercultural research between Spain and Portugal). The age range of the total sample was 18 to 30 years (Mage = 20.37, SD = 2.50). presents the distribution of the sample in accordance with participants’ sociodemographic characteristics.

Table 1 Sample Characteristics

Data Collection

A formal request to explain the aims of the study and ask students for their permission to gather information was sent by Email to faculty members. After they had agreed, participants anonymously and voluntarily completed the self-report Measures in the form of an online survey that took roughly 20 minutes. Measures were completed in participants’ classrooms in the presence of a member of the research team. Data were collected between the autumn of 2022 and the spring of 2023 and participants’ consent was obtained on the first page of the online survey. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciencias da Educação da Universidade do Porto in Portugal (Refª 2017/10-2c) and complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

Sociodemographic Variables

Sociodemographic variables included country (0 = Portugal, 1 = Spain), gender (0 = female, 1 = male), sexual orientation (0 = heterosexual, 1 = LGB-gay, lesbian or bisexual) and residence status (0 = co-resident with parents, 1 = non co-resident with parents). Moreover, socioeconomic status (SES) was measured using an ad hoc scale developed by the research team, on which participants were asked to rate the income level of their family unit on a 3-point scale ranging from 1 (low-perception of serious economic difficulties) to 3 (high-perception of having a high enough income to live comfortably).

Intergenerational Solidarity

To assess intergenerational solidarity, all participants completed five subscales (affective, conflictual, associational, functional and normative solidarity) of the Intergenerational Solidarity Index.Citation12 All subscales on this instrument are rated on Likert-type response scales, but with different ranges and meanings. The affective solidarity subscale comprises 5 items ranging from 1 (Not at all close or Not at all good) to 6 (Extremely close or Extremely Good or Extremely well) and assesses respondents’ level of emotional closeness to their parents (eg, “Overall, how well do you and your parents get along together at this point in your life?”). The conflictual solidarity subscale comprises 3 items ranging from 1 (None at all) to 6 (A great deal) and assesses the frequency of conflict between parents and children (eg, “How much do your parents argue with you?”). The associational solidarity subscale comprises 5 items ranging from 1 (Daily) to 8 (Not at all) and assesses the frequency of in-person, telephone, letter, Email or social media contact with parents by asking participants: “During the past year, how often were you in contact with your parents?”. The functional solidarity subscale comprises 8 items ranging from 1 (Daily) to 8 (Not at all), and assesses the instrumental (eg, household chores, transportation/shopping) and emotional support (eg, information and advice, discussing important life decisions) provided by children to parents by asking participants, “For each type of help and support listed below, put a check in the box beneath each person to whom you provide that kind of assistance or support”. The normative solidarity subscale comprises 6 items ranging from 1 (Strongly agree) to 4 (Strongly disagree) and assesses respondents’ expectations about their obligations and the importance of family values (eg, “Family members should give more weight to each other”s opinions than to the opinions of outsiders’). Mean scores are calculated for all subscales except the associational solidarity subscale, for which maximum frequency of contact is calculated. Higher scores indicate higher levels of intergenerational solidarity. Adequate levels of internal reliability were found in this study (αPortugal= 0.92, αSpain= 0.90, αTotal= 0.91 for affective solidarity; αPortugal= 0.85, αSpain= 0.80, αTotal= 0.83 for conflictual solidarity; αPortugal= 0.81, αSpain= 0.82, αTotal= 0.82 for functional solidarity; and αPortugal= 0.72, αSpain= 0.78, αTotal= 0.75 for normative solidarity).

Psychological Distress

To assess psychological distress, all participants completed the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21).Citation31 This instrument includes 21-items rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much, or most of the time), which measure three subscales: depression, anxiety and stress, grouped into a second-order factor labelled psychological distress (eg, “I felt sad and depressed”). Response scores are summed to generate a mean score for the data analyses. Higher scores indicate higher levels of psychological distress (αPortugal= 0.92, αSpain= 0.89, αTotal= 0.91).

Satisfaction with Life

To assess satisfaction with life, all participants completed the Satisfaction with Life Scale.Citation32 This scale comprises 5 items (eg, “The conditions of my life are excellent”) rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). Response scores are summed to generate a mean score for the data analyses. Higher scores indicate higher levels of satisfaction with life (αPortugal= 0.80, αSpain= 0.86, αTotal= 0.83).

Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 and MedGraph programs.Citation33 First, descriptive statistics were obtained, including a summary of participants’ sociodemographic data, as well as means and standard deviations (SDs) of each intergenerational solidarity dimension. Second, independent sample t-tests, one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and Bonferroni post hoc tests were conducted to test the significance of means differences in intergenerational solidarity in accordance with sociodemographic variables (country, gender, sexual orientation, co-residence status, age and SES). Third, to explore associations between intergenerational solidarity and psychological distress and satisfaction with life, inter-correlations between the study variables were calculated using the Pearson correlation. Moreover, mediation analyses were conducted to determine whether affective solidarity mediated the relationship between the remaining intergenerational solidarity dimensions (conflictual, associational, functional and normative solidarity) and psychological distress and satisfaction with life. These analyses were conducted for psychological distress and satisfaction with life separately. Furthermore, country, gender, co-residence/non co-residence with parents, sexual orientation and SES were included as control variables in the analyses. Thus, in each mediation analysis, two linear regression models were considered, one for the relationship between the independent (conflictual, associational, functional or normative solidarity) and the mediating variable, and another for the relationship between the mediating variable and each of the dependent variables (psychological distress and satisfaction with life). The online MedGraph programCitation33 was used to graph the results, calculate the Sobel z-value and test the significance of the mediating effect of affective solidarity on the association between the rest of the intergenerational solidarity dimensions (conflictual, associational, functional and normative solidarity) and psychological distress and satisfaction with life. The models generated 95% bias-corrected and adjusted confidence intervals for the indirect effect. Sobel’s methodCitation34,Citation35 was used as a widely-employed test of the simple mediation effect (indirect effect) in large samples, which allows researchers to determine whether the strength of the relationship between the independent variable (in our case, conflictual, associational, functional or normative solidarity) and the dependent variable (in our case, psychological distress or satisfaction with life) is significantly reduced (partial mediation) or annulled (full mediation) following the addition of a mediating variable (in our case, affective solidarity).

Results

Differences in Accordance with Sociodemographic Characteristics

The Results of the t-tests for independent samples revealed significant differences for some dimensions of intergenerational solidarity in accordance with country, gender, residence status (whether or not participants lived with their parents) and sexual orientation (see ). Specifically, Portuguese emerging adults perceived higher levels of conflictual solidarity than their Spanish counterparts, whereas Spanish emerging adults perceived higher levels of associational, functional and normative solidarity than their Portuguese peers. Moreover, emerging adult men perceived higher levels of normative solidarity than their female counterparts, and emerging adults who did not co-reside with their parents perceived higher levels of affective solidarity than those who did. In contrast, emerging adults who lived under the same roof as their parents perceived higher levels of conflictual, associational and functional solidarity than their independent-living counterparts. Finally, heterosexual participants perceived higher levels of affective, functional and normative solidarity than gay, lesbian or bisexual emerging adults, who in turn perceived higher levels of conflictual solidarity than their heterosexual counterparts (see ).

Table 2 Independent Sample t-Tests for Intergenerational Solidarity

One-way ANOVAs revealed that the three SES groups analysed differed in terms of affective solidarity, F(2, 633) = 5.44, p = 0.005, conflictual solidarity, F(2, 631) = 3.35, p = 0.036 and associational solidarity F(2, 633) = 3.27, p = 0.039. With regard to affective solidarity, the Bonferroni post hoc test revealed differences between the low SES and high SES groups (Mean Difference = −0.53; p = 0.003), with a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = −0.55), with emerging adults from the high SES group scoring higher in this dimension. With regard to conflictual solidarity, the post hoc test revealed differences between the low SES and medium SES groups (Mean Difference = 0.30; p = 0.032), with a small effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.33), with emerging adults from the low SES group scoring higher. Finally, regarding associational solidarity, the post hoc test also revealed differences between the low SES and medium SES groups (Mean Difference = −0.12; p = 0.045), with a small effect size (Cohen’s d = −0.34). In this case, emerging adults from the medium SES group scored higher for associational solidarity.

Inter-Correlations Between Study Variables

shows the inter-correlations between the different intergenerational solidarity dimensions, satisfaction with life and psychological distress. The results indicated that only conflictual solidarity was negatively and significantly associated with satisfaction with life. In contrast, the remaining intergenerational solidarity dimensions (affective, associational, functional and normative solidarity) were positively and significantly associated with satisfaction with life. In terms of psychological distress, conflictual solidarity was the only dimension that was positively and significantly associated with this variable. In contrast, the affective, associational, and normative dimensions were negatively and significantly associated with psychological distress. Functional solidarity was not significantly associated with this variable.

Table 3 Inter-Correlations Between Study Variables

The Mediating Role of Affective Solidarity in the Relationship Between Solidarity Dimensions and Psychological Distress and Satisfaction with Life

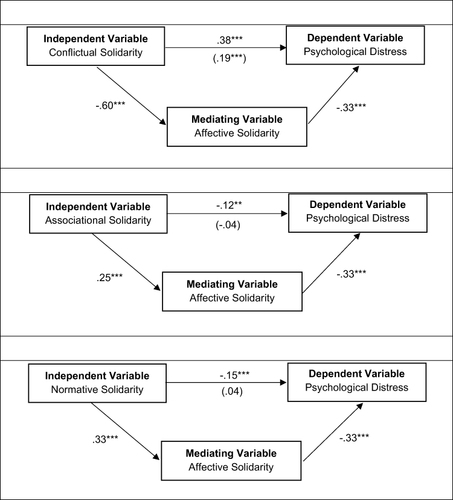

, and summarise the results pertaining to the mediating role of affective solidarity. Affective solidarity was found to partially mediate the relationship between conflictual solidarity and psychological distress, as the direct effect of the former on the latter variable decreased when the mediating role of affective solidarity was analysed. Specifically, emotional closeness to parents helped mitigate the positive association between conflictual solidarity and psychological distress. Furthermore, affective solidarity was found to fully mediate the relationship between associational and normative solidarity and psychological distress. High frequency of contact with parents (associational solidarity), strong family values and a strong sense of family obligation (normative solidarity) were found to lead to more emotional closeness to parents, which in turn mitigated the psychological distress suffered by emerging adult offspring. In relation to functional solidarity, affective solidarity was not found to mediate the relationship between this dimension of intergenerational solidarity and psychological distress.

Table 4 Mediating Effect of Affective Solidarity Between Conflictual, Associational, Functional and Normative Solidarity and Psychological Distress and Satisfaction with Life

Figure 1 MedGraph showing the mediating effect of affective solidarity in the association between conflictual, associational and normative solidarity and psychological distress.

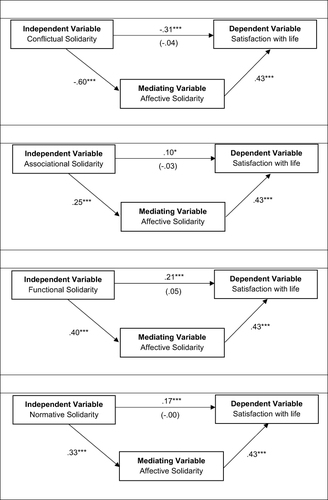

Figure 2 MedGraph showing the mediating effect of affective solidarity in the association between conflictual, associational, functional and normative solidarity and satisfaction with life.

With regard to satisfaction with life, affective solidarity was found to fully mediate the impact of conflictual, associational, functional and normative solidarity on this adjustment variable. The results indicated that emotional closeness to parents helped mitigate the (in this case negative) association between conflictual solidarity and satisfaction with life. Furthermore, frequent contact with parents (associational solidarity), the provision of instrumental and emotional support (functional solidarity), having a strong sense of family obligation and attaching greater weight to family values (normative solidarity) were found to contribute to greater emotional closeness to parents, which in turn enhanced satisfaction with life.

Discussion

The present study aimed to explore patterns in intergenerational solidarity among emerging adults and their parents in two Southern European countries. Firstly, differences in accordance with country and other sociodemographic characteristics were explored. Next, associations between the different dimensions of intergenerational solidarity and emerging adults’ psychological adjustment were analysed, exploring the mediating effect of affective solidarity.

Our results suggest some differences in intergenerational solidarity patterns in accordance with country. Specifically, Spanish emerging adults perceived higher levels of associational, functional and normative solidarity than their Portuguese counterparts, who in turn perceived higher levels of conflictual solidarity. As noted previously, as Southern European countries, Spain and Portugal have very similar parent-child relationship patterns within the family system, which is characterised by strong, close family ties and offspring remaining in the parental home for longer.Citation20 However, previous research has already found differences between these two Southern European countries in other family variables, with Spanish emerging adults, for example, reporting higher levels of parental involvement than their Portuguese counterparts.Citation36 One possible explanation for the higher levels of conflictual solidarity perceived by Portuguese than Spanish emerging adults may be linked to the average age at which young people leave the parental home, which is higher in Portugal than in Spain (33.6 vs 28.9, respectively).Citation8 The fact that adult children spend or anticipate spending more years living under the same roof as their parents makes it more likely for conflicts to arise in those families than in those in which offspring leave home at an earlier (although still late) age, as is the case in Spain. Our results seem to support this idea, since emerging adults who do not live with their parents perceive higher levels of affective solidarity and lower levels of conflictual, associational and functional solidarity than their counterparts who continue to live in the parental home. Indeed, the results of previous studies indicate that parent-child relationships improve after offspring leave the family home.Citation37

Regarding gender differences, emerging adult men reported higher levels of normative solidarity than their female counterparts. This finding can be explained in terms of the general traditional male role that is particularly prevalent in Southern European countries, and is mostly focused on a sense of family duty. In this context, men usually assume more responsibility in relation to family values and perceive their role within the family as being linked to the provision of financial and instrumental aid. Everyday chores involving care and support for those who are most in need and/or least autonomous (eg, children and the elderly) are, in general, perceived as pertaining to the traditional female role.Citation14 This may be why men usually perceive higher levels of this intergenerational dimension, which is defined by strength of commitment to performing family roles and meeting family obligations, often as a means of maintaining status and power within families and society.Citation12 Although traditional gender roles and stereotypes are less prevalent today than in previous decades, they continue to be present.Citation14 Indeed, research has found that these traditional, normative gender roles can still discourage men from providing certain types of support that are traditionally attributed to womenCitation38 and may pose a challenge to their work-family-personal life balance. Regarding sexual orientation, LGB emerging adults reported lower levels of affective, functional and normative solidarity and higher levels of conflictual solidarity than their heterosexual counterparts. These findings are consistent with recent research focused on this life stage in Portugal.Citation19 Indeed, some authors suggest that, at least during adolescence, members of sexual minorities continue to have poorer family relationships (eg, less parental support, less family connectedness, more strained parent–child relationships) than heterosexual children.Citation39–41 Finally, our results show that emerging adults from families with a high SES perceived the highest levels of affective solidarity, those from families with a low SES perceived the highest levels of conflictual solidarity, and those from families with a medium SES perceived the highest levels of associational solidarity. These findings are partially consistent with those reported by studies carried out in Northern Europe,Citation18 which found stronger and more positive intergenerational solidarity during this life stage among those from families with a low and middle SES. It is often assumed that, in general, a higher SES is linked to closeness in family relationships, more frequent contact and less frequent conflict between family members.Citation42 Accordingly, our results also corroborate others found in Southern European countriesCitation43 that suggest that, in general, emerging adults who perceive a better financial situation in their families also perceived more positive family relationships. However, it is also true that studies do not always take into account how financial difficulties in the family may lead to intergenerational ambivalence (irreconcilable contradictions in the relationship between parents and their adult offspring).Citation14 In this regard, families’ financial resources may vary in accordance with sociocultural context. Southern European countries are characterised by low levels of youth employment and low social expenditure.Citation44 This in turn may lead to individuals having fewer resources to guarantee an autonomous life, rendering them more vulnerable to stress linked to the scarcity of economic resources, a circumstance that may affect family dynamics.

Overall, our findings indicate that emerging adults who report higher levels of conflictual solidarity have lower levels of satisfaction with life and higher levels of psychological distress. In contrast, emerging adults who report higher levels of affective, associational, functional and normative solidarity have higher levels of satisfaction with life and (with the exception of functional solidarity) lower levels of psychological distress. These findings were expected, particularly given that previous studies have already suggested that intergenerational solidarity may be a valuable construct for exploring psychological development and adjustment during emerging adulthood.Citation26,Citation28 In this sense, our results suggest that enjoying positive and healthy family relationships, characterised by closeness, high frequency of contact, mutual support and high levels of family values, is linked to positive development among emerging adult offspring; whereas, strained and conflictive relationships between generations are linked to negative development during this life stage, at least in Southern European countries such as Portugal and Spain.

As hypothesised, affective solidarity significantly mediated the relationship between the other intergenerational dimensions and emerging adults’ adjustment. Interestingly, our findings extend the existing body of knowledge by specifically demonstrating that not only are conflictive, associational, functional and normative solidarity significantly associated (positively or negatively) with emerging adults’ satisfaction with life and (with the exception of functional solidarity) psychological distress, but that these associations may be weakened or even annulled altogether by the inclusion of affective solidarity as a mediating variable. This suggests that this intergenerational solidarity dimension (affective solidarity) plays an essential role in these relationships. Higher levels of interactions and shared activities, greater provision of instrumental and emotional support, more exchanges of assistance, and stronger endorsement of family roles and obligations between family members are reflected in higher levels of satisfaction with life and (with the exception of emotional support) lower levels of psychological distress. It is important to highlight the fact that most of these effects are mediated by affective solidarity: associative, functional and normative solidarity generate affective solidarity, which in turn results in better adjustment. In other words, positive emotions towards family members generate an atmosphere that is more conducive to healthy psychological development. In the case of conflictual solidarity, conflict with parents decreases emerging adults’ satisfaction with life and increases their psychological distress. In contrast, and similarly to the other dimensions of intergenerational solidarity (associative, functional and normative), warmth, closeness, understanding, trust and respect from family members generate a better setting for offspring’s psychological development, resulting in a weakening of the direct relationship between conflictual solidarity and psychological distress (partial mediation) and the elimination of the direct relationship between this same dimension and satisfaction with life (full mediation). This latter effect implies that conflictive solidarity only influences satisfaction with life through affective solidarity. Our findings are, in general, consistent those reported by studies carried out previously in the United States of America that observed the mediating effect of affective solidarity between some intergenerational solidarity dimensions, such as normative solidarity, and some predictors of emerging adults’ psychological maladjustment.Citation26 However, going one step further, our results highlight the importance of the affective dimension within intergenerational solidarity in Southern European countries during emerging adulthood. Our findings therefore expand on the scarce extant literature by specifically demonstrating the mediating role of affective solidarity in the relationship between the other intergenerational solidarity dimensions and emerging adults’ satisfaction with life and (with the exception of functional solidarity) psychological distress. It is worth noting that, in order to offer a possible explanation for the particular importance of affective solidarity among family members suggested by our results, we must again refer to the sociocultural context of Southern Europe. It is hardly surprising that, in a context in which two adult generations spend several years under the same roof and family constitutes the main source of instrumental and emotional support,Citation45 it is especially important for offspring’s positive development that parent-child relationships be defined by affection, closeness and mutual respect. Furthermore, it seems that parents and emerging adult offspring from Southern Europe, and more specifically from Spain and Portugal, perceive low levels of conflict between family members. Specifically, previous research conducted in this region found a low-medium level of conflictual solidarityCitation19 and a decrease in conflictual parent-child relationshipsCitation46 during this stage in comparison with previous years. This may help explain why, as a mediating variable, affective solidarity exerts a weaker effect (partial mediation) on the association between conflictual solidarity (a dimension that starts from already low levels) and psychological distress.

The present study has some limitations, the first being the use of an emerging adult sample comprised exclusively of university students. Although university students constitute a large segment of the emerging adult population, there are several important differences in the experience of university students and non-university-attending individuals in a number of key demographic, socioeconomic and psychosocial variables.Citation47 It is therefore important to include both types of emerging adult in future studies. A second limitation is that the sample was predominately made up of young emerging adults (Mage = 20.37). Further research is required to examine the entire age range of this developmental stage. Third, the majority of participants were women (80.2% females). Although there are currently more women than men attending university in both Spain and Portugal,Citation5,Citation48 future research should make an effort to ensure balanced samples in terms of gender.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, the present study contributes to the literature on intergenerational solidarity theoryCitation11,Citation12 during emerging adulthood in several ways. Different patterns of intergenerational solidarity were found in accordance with a range of sociodemographic characteristics, indicating that it is important to take sociodemographic diversity into account when analysing the relationships that exist between emerging adults and their parents. Moreover, the present study also highlights the fact that there are significant associations between the different dimensions of intergenerational solidarity and emerging adult’s adjustment, and that these associations are mediated by affective solidarity. It therefore seems that, in general, intergenerational solidarity, which has traditionally been used to study the relationship between elderly people and their adult children, is also an important multidimensional construct for exploring relationships between emerging adults and their parents. Family intergenerational solidarity, and particularly the affective dimension of this construct, acts as a protective factor in promoting emerging adults’ adjustment. The present study helps deepen our understanding of the sociocultural specificities of the transition to adulthood in societies in which family values are high and state support is low, a situation that has implications not only for individual and family well-being, but also for the country’s medium-term economic sustainability, through the renovation of generations. Southern European countries such as Spain and Portugal rely mostly on families to compensate for the structural obstacles faced by young people during their transition to adulthood. It is therefore important to consider the power imbalances suggested by the differences observed in terms of socioeconomic status, gender and sexual identity and/or orientation. Our findings may also have important implications for practice, helping inform policy recommendations. It is important to facilitate and, if possible, strengthen positive and close emotional ties between parents and their emerging adult offspring, as well as to offer public support for those who do not enjoy such ties and may be in a situation of vulnerability, exposed to the adversities of youth unemployment, precariousness, and the housing crisis.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Acknowledgments

This research study was funded by a Margarita Salas postdoctoral fellowship grant from the Ministerio de Universidades (Spanish Ministry of Universities), the Spanish Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan and European Union – NextGenerationEU. The study was also funded by the Centre for Psychology at the University of Porto, the Portuguese Science Foundation (FCT UID/PSI/00050/2019) and the Conserjería de Transformación Económica, Industria, Conocimiento y Universidades de la Junta de Andalucía (Andalusian Regional Ministry for Economic Transformation, Industry, Knowledge and Universities (PROYEXCEL_00766).

References

- Suitor JJ, Gilligan M, Pillemer K, et al. Applying within-family differences approaches to enhance understanding of the complexity of intergenerational relations. J Gerontol B. 2018;73(1):40–53. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbx037

- Bengtson VL, Oyama PS. Intergenerational solidarity and conflict: what does it mean and what are the big issues? Intergenerat Solid. 2010;2010:35–52.

- Moreno L, Marí-Klose P. Youth, family change and welfare arrangements: is the South still so different? Europ Soc. 2013;15(4):493–513. doi:10.1080/14616696.2013.836400

- Arnett JJ. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties. 3nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2023. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197695937.001.0001

- Ministerio de Universidades. Gobierno de España. Datos y cifras del Sistema Universitario Español. Publicación 2022–2023 [Data and figures of the Spanish University System. 2022–2023 publication]. Madrid: Ministerio de Universidades. Spainsh; 2023. Available from: https://www.universidades.gob.es/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/DyC_2023_web_v2.pdf. Accessed June 05, 2024.

- Eurostat. Labour force survey; 2022. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-labour-force-survey. Accessed June 05, 2024.

- Statistical Office of the European Union (Eurostat). Youth unemployment by sex, age and educational attainment level. Products Datasets. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2023a. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/yth_empl_090/default/table?lang=en. Accessed June 05, 2024.

- Statistical Office of the European Union (Eurostat). Estimated average age of young people leaving the parental household by sex. Products Datasets. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2023b. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/yth_demo_030/default/table?lang=en. Accessed June 05, 2024.

- Statistical Office of the European Union (Eurostat). Mean age at first marriage by sex. Products Datasets. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2023c. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/TPS00014/default/table?lang=en. Accessed June 05, 2024.

- Statistical Office of the European Union (Eurostat). Mean age of women at childbirth and at birth of first child. Products Datasets. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2023d. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/TPS00017/default/table?lang=en. Accessed June 05, 2024.

- Bengtson VL. Beyond the nuclear family: the increasing importance of multigenerational bonds: the burgess award lecture. J Marr Family. 2001;63(1):1–16. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00001.x

- Bengtson VL, Roberts RE. Intergenerational solidarity in aging families: an example of formal theory construction. J Marriage Family. 1991;53:856–870. doi:10.2307/352993

- Bengtson V, Giarrusso R, Mabry JB, Silverstein M. Solidarity, conflict, and ambivalence: complementary or competing perspectives on intergenerational relationships? J Marriage Family. 2002;64:568–576. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00568.x

- Coimbra S, Ribeiro L, Fontaine AM. Intergenerational solidarity in an ageing society: sociodemographic determinants of intergenerational support to elderly parents. In: Albert I, Ferring D, editors. Intergenerational Relations: European Perspectives on Family and Society. Bristol: The Policy Press; 2013:pp. 205e222. doi:10.1332/policypress/9781447300984.003.0013

- Komter AE, Vollebergh WA. Solidarity in Dutch families: family ties under strain? J Family Issues. 2002;23(2):171–188. doi:10.1177/0192513X02023002001

- Stein CH, Wemmerus VA, Ward M, Gaines ME, Freeberg AL, Jewell TC. Because they’re my parents”: an intergenerational study of felt obligation and parental caregiving. J Marriage Family. 1998;60:611–622. doi:10.2307/353532

- Lee J, Park J, Kim H, Oh S, Kwon S. Typology of young Korean adults’ relationships with their parents from an intergenerational solidarity lens. Fam Environ Res. 2020;58(1):43–60. doi:10.6115/fer.2020.004

- Timonen V, Conlon C, Scharf T, Carney G. Family, state, class and solidarity: re-conceptualising intergenerational solidarity through the grounded theory approach. Europ J Age. 2013;10:171–179. doi:10.1007/s10433-013-0272-x

- Leal D, Gato J, Coimbra S. How does sexual orientation influence intergenerational family solidarity? An exploratory study. J Prev Intervent Comm. 2019;48(4):382–393. doi:10.1080/10852352.2019.1627081

- Alesina A, Giuliano P. Family Ties. In: Aghion P, Durlauf S, editors. Handbook of Economic Growth. The Netherlands: North Holland; 2014:177–215.

- Haberkern K, Szydlik M. State care provision, societal opinion and children’s care of older parents in 11 European countries. Ageing Soc. 2010;30(2):299–323. doi:10.1017/S0144686X09990316

- Montoro-Gurich C, Garcia-Vivar C. The family in Europe: structure, intergenerational solidarity, and new challenges to family health. J Fam Nurs. 2019;25(2):170–189. doi:10.1177/1074840719841404

- Ge X, Natsuaki MN, Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D. The longitudinal effects of stressful life events on adolescent depression are buffered by parent–child closeness. Develop Psychopathol. 2009;21:621–635. doi:10.1017/S0954579409000339

- Hazer O, Öztürk MS, Gürsoy N. Effects of intergenerational solidarity on the satisfaction with life. Internat J Arts Sci. 2015;8(1):213.

- Szcześniak M, Tułecka M. Family functioning and life satisfaction: the mediatory role of emotional intelligence. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;223–232. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S240898

- Lee CYS, Dik BJ, Barbara LA. Intergenerational solidarity and individual adjustment during emerging adulthood. J Family Issues. 2016;37(10):1412–1432. doi:10.1177/0192513X14567957

- Fuligni AJ, Pedersen S. Family obligation and the transition to young adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(5):856. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.38.5.856

- Coimbra S, Mendonça MG. Intergenerational solidarity and satisfaction with life: mediation effects with emerging adults. Paidéia. 2013;23:161–169. doi:10.1590/1982-43272355201303

- Kenny ME. The extent and function of parental attachment among first-year college students. J Youth Adolesc. 1987;16(1):17–29. doi:10.1007/BF02141544

- Birditt KS, Miller LM, Fingerman KL, Lefkowitz ES. Tensions in the parent and adult child relationship: links to solidarity and ambivalence. Psychol Aging. 2009;24(2):287. doi:10.1037/a0015196

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav Res Therap. 1995;33(3):335–343. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

- Diener ED, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Personal Assessm. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Jose PE. Doing Statistical Mediation and Moderation. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013.

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Person Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Sobel ME. Effect analysis and causation in linear structural equation models. Psychometrika. 1990;55:495–515. doi:10.1007/BF02294763

- García-Mendoza MC, Parra A, Sánchez-Queija I, Oliveira JE, Coimbra S. Gender differences in perceived family involvement and perceived family control during emerging adulthood: a cross-country comparison in Southern Europe. J Child Family Stud. 2021;31(4):1007–1018. doi:10.1007/s10826-021-02122-y

- Whiteman SD, McHale SM, Crouter AC. Family relationships from adolescence to early adulthood: changes in the family system following firstborns’ leaving home. J Res Adolescence. 2011;21(2):461–474. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00683.x

- Campbell LD, Martin-Matthews A. Primary and proximate: the importance of coresidence and being primary provider of care for men’s filial care involvement. J Family Issues. 2000;21(8):1006–1030. doi:10.1177/019251300021008004

- Darby-Mullins P, Murdock TB. The influence of family environment factors on self-acceptance and emotional adjustment among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents. J GLBT Family Stud. 2007;3(1):75–91. doi:10.1300/J461v03n01_04

- Eisenberg ME, Resnick MD. Suicidality among gay, lesbian and bisexual youth: the role of protective factors. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(5):662–668. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.024

- Needham BL, Austin EL. Sexual orientation, parental support, and health during the transition to young adulthood. J Youth Adolesce. 2010;39:1189–1198. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9533-6

- Szydlik M. Intergenerational solidarity and conflict. J Comp Family Stud. 2008;39(1):97–114. doi:10.3138/jcfs.39.1.97

- García-Mendoza MC, Sánchez Queija I, Parra Jiménez Á. The role of parents in emerging adults’ psychological well‐being: a person‐oriented approach. Family Process. 2019;58(4):954–971. doi:10.1111/famp.12388

- Vogel J. European welfare regimes and the transition to adulthood: a comparative and longitudinal perspective. Soc Indic Res. 2002;59(3):275–299. doi:10.1023/A:1019627604669

- Lee C-YS, Goldstein SE. Loneliness, stress, and social support in young adulthood: does the source of support matter? J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45(3):568–580. doi:10.1007/s10964-015-0395-9

- Parra A, Oliva A, Reina MC. Family relationships from adolescence to emerging adulthood: a longitudinal study. J Family Issues. 2015;36(14):2002–2020. doi:10.1177/0192513X13507570

- Schwartz SJ. Turning point for a turning point: advancing emerging adulthood theory and research. Emerging Adulthood. 2016;4(5):307–317. doi:10.1177/2167696815624640

- Pordata. Estatísticas sobre Portugal e Europa. Alunos do sexo feminino em % dos matriculados no ensino superior: total e por área de educação e formação [Statistics about Portugal and Europe. Female students in % of those enrolled in higher education: total and by area of education and training]. Portuguese; 2022. Available from: https://www.pordata.pt/portugal/alunos+do+sexo+feminino+em+percentagem+dos+matriculados+no+ensino+superior+total+e+por+area+de+educacao+e+formacao+-1051. Accessed June 05, 2024.