Abstract

Introduction

Changes in biological rhythm are among the various characteristics of bipolar disorder, and have long been associated with the functional impairment of the disease. There are only a few viable options of psychosocial interventions that deal with this specific topic; one of them is psychoeducation, a model that, although it has been used by practitioners for some time, only recently have studies shown its efficacy in clinical practice.

Aim

To assess if patients undergoing psychosocial intervention in addition to a pharmacological treatment have better regulation of their biological rhythm than those only using medication.

Method

This study is a randomized clinical trial that compares a standard medication intervention to an intervention combined with drugs and psychoeducation. The evaluation of the biological rhythm was made using the Biological Rhythm Interview of Assessment in Neuropsychiatry, an 18-item scale divided in four areas (sleep, activity, social rhythm, and eating pattern). The combined intervention consisted of medication and a short-term psychoeducation model summarized in a protocol of six individual sessions of 1 hour each.

Results

The sample consisted of 61 patients with bipolar II disorder, but during the study, there were 14 losses to follow-up. Therefore, the final sample consisted of 45 individuals (26 for standard intervention and 19 for combined). The results showed that, in this sample and time period evaluated, the combined treatment of medication and psychoeducation had no statistically significant impact on the regulation of biological rhythm when compared to standard pharmacological treatment.

Conclusion

Although the changes in biological rhythm were not statistically significant during the time period evaluated in this study, it is noteworthy that the trajectory of the score showed a trend towards improvement, which may indicate a positive impact on treatment, though it may take a longer time than expected.

Introduction

Changes in biological rhythm are among the various characteristics of bipolar disorder (BD) and have long been associated with the functional impairment of the disease,Citation1 with damages that may persist even during remission, such as subsyndromic symptoms and risk of relapse.Citation2 These changes occur mainly due to sleep disturbancesCitation3 (that can be related to allelic mutations on clock genesCitation4), changes in routine,Citation1 and stressful life events.Citation5 It has also been suggested that bipolar subjects secrete abnormal levels of melatonin and are hypersensitive to light, which can affect their sleep patterns.Citation6 Disruptions in the biological rhythm of subjects with BD can trigger acute episodes; for example, there are clear links between sleep disturbances and mania.Citation7 A poor repertoire of coping skills to face social rhythm disruptions may compromise the maintenance of a euthymic state of the subjects, resulting in a series of failed attempts of regulation.

Although pharmacotherapy is an indispensable primary option for the treatment of BD, it is interesting to offer viable options of psychosocial interventions in order to improve pharmacological treatment adherence, coping skills, and the patient’s quality of life.Citation8 These interventions are increasingly recognized as an essential component in the treatment of BD.Citation9,Citation10 Successful psychosocial interventions for unipolar depression such as adjunctive family therapy,Citation11,Citation12 cognitive behavioral therapy,Citation13 and interpersonal and social rhythm therapyCitation14 were adapted for BD and evaluated by trials, and are associated with greater symptom stabilization and change of habits. However, not all are equally effective, and the long-term effects do not indicate a significant improvement over conventional therapy.

Among all psychosocial interventions, psychoeducation (PE) has been one of the most used and is recommended by several guidelinesCitation15,Citation16 as a first choice for BD due to its appeal to a wider population and because of its straightforward and cost-effective profile. PE is recommended for pharmacological adherence enhancement, knowledge, and awareness of the disease.Citation17 It is particularly helpful for subjects to learn how to detect prodromal signs of the disease and, consequently, to prevent relapses.Citation18,Citation19 Although PE is an intervention model that has been used by practitioners for some time, only recently have studies with reliable methodology shown its efficacy in clinical practice.Citation20–Citation23 A recent systematic review by BatistaCitation24 identified a total of 13 randomized clinical trials evaluating PE in BD. Briefly, these studies evaluated PE in different samples (BD-only subject, relatives/caregivers, or both), both in groups and individually. The number of sessions ranged from five to 21 meetings, and the follow-ups ranged from 6 months to 5 years. The results of the review indicate that PE is an intervention particularly effective in decreasing the relapse rate (both manic and depressive) and in improving overall social functioning. However, as pointed out by the authors, the mechanism of action of PE remains unknown. Their primary hypothesis states that teaching lifestyle regularity is the main aspect and may play a role in relapse prevention due to early detection of prodromal symptoms.

BD is a neuroprogressive disease, longitudinally associated with increased severity and an accelerated disability. One of the concepts that attempts to explain why BD worsens over time is allostatic load (AL). AL discusses the cumulative effects of an overload of the adaptative systems due to the typical chronic overactivity of the disease.Citation25 The AL increases progressively as stressors and mood episodes occur over time, and is connected to the cognitive impairment of BD, which includes attention, executive function, and verbal memory.Citation26

Since the first mood episodes are happening earlier (the typical age of onset is 23 years) and severe symptoms are unfolding earlier, there is a possibility of higher severity of BD in younger generations.Citation27 We wondered whether a psychosocial intervention applied in younger patients, who have a shorter disease duration, fewer mood episodes, and reduced cognitive impairment, can have a different impact on regulating their biological rhythms. For this purpose, we carried out a study with young adults, aged between 18–29 years, diagnosed with BD, in which we compared a standard intervention (pharmacological with mood stabilizers) and a combined intervention of drugs and a short-term PE model.Citation28 Although studies that showed the effectiveness of PE for the treatment of BDCitation18,Citation29 had a similar design (randomized clinical trial), the sampling and the intervention design were significantly different. We do not know of any study that has evaluated a short-term individual PE intervention for bipolar subjects in a sample formed exclusively of young adults with no previous treatment.

Aim

The aim of this study was to assess if subjects undergoing psychosocial intervention in addition to a pharmacological treatment could have better regulation of their biological rhythms than those who were only using medication.

Method

Design and setting

This study is a randomized clinical trial that evaluated the influence of PE on regulating the biological rhythm of individuals with Bipolar II Disorder by comparing a standard medication intervention to an intervention combined with drugs and PE. The project was approved by the Ethics Committee on Research of Catholic University of Pelotas (UCPel), according to protocol No 2009/24, and all participants signed the informed consent.

In order to ensure the necessary sample size to estimate the effectiveness of the interventions, the trial was advertised in public health care units, psychosocial care centers, outpatient clinics, and city hospitals. The subjects recruited in these places were selected as follows. Those who agreed to participate were evaluated by a semi-structured clinical interview (SCID-I [Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders]) in order to ensure diagnostic reliability. This interview model is based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Edition – Text Revision, with a translation and adaptation to Portuguese that presents, in general, good reliability, with an excellent Kappa coefficient (0.87) for mood disorders.Citation30 The interviews were conducted by two PhD students, who underwent intensive training under the supervision of a senior researcher. After the bipolar II diagnosis was validated, the subjects were referred to the psychiatric services of the public health system. However, due to the difficulty in obtaining medication in the public health system in the city of Pelotas, a city in southern Brazil with a population of 350,000, a psychiatrist had to be assigned to the research team and the subjects were referred to the psychiatric outpatient clinic of the Health Campus of UCPel. The medicated subjects that matched the inclusion criteria (aged between 18–29 years, a validated clinical diagnosis of bipolar II according to SCID, and gave their informed consent) were invited to participate in the trial. Those with suicide risk and/or using illegal drugs were not included and were offered treatment at a specialized outpatient facility. The Economic Index was assessed with the National Economic Index,Citation31 based on the total of material goods and the householders’ schooling, among other items. The socioeconomic classes were divided into three levels (high, intermediate, and low) for the Brazilian population according to the 2000 Demographic Census.

Outcome measures

The severity of depressive symptoms was measured with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, a 17-item scale that enables the creation of a discrete variable, in which the higher scores correspond to a higher severity of the symptoms. The internal consistency ranges from 0.83 to 0.94. The scale reliability between raters has been consistent in several studies.Citation32 To assess the intensity of manic symptoms, we utilized the Young Mania Rating Scale, an eleven-item scale chosen for its high reliability in measuring severity levels of mania and validity coefficient. The Brazilian validated version,Citation33 which has an even better reliability level than the original, had its internal consistency assessed by Cronbach’s α, calculated using analysis of variance applied to the eleven items of the scale. From the resulting covariance matrix, α =0.67 was obtained for the scale as a whole, and α =0.72 for each standardized item (P<0.001).

The evaluation of the biological rhythm was made using the Biological Rhythm Interview of Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (BRIAN). This scale was designed to offer a reliable, validated, and standardized measure of biological rhythm, with scores clinically understandable for researchers. The 18 items are divided in four specific areas (sleep, activity, social rhythm, and eating pattern) that are rated using a four-point scale: 1 (no difficulty) to 4 (very difficult). The validity and reliability of the Portuguese BRIAN version are described by Giglio et al,Citation34 including information about its factor analysis and how the areas were selected. All the outcome measures were assessed in two different time points: baseline and postintervention.

Randomization

Participants were randomly divided into two groups using sealed envelopes: one group received a short-term PE modelCitation28 and medication (combined intervention), and the other received only medication (standard intervention). The randomization was made by a team member who did not participate in any of the previous stages of the study. Those who administered the intervention were not blind as to the absence or presence of PE associated with drug intervention. However, blinding of the baseline and postintervention evaluators was guaranteed (they were always blinded to subject allocation) by changing the team for each evaluation time point.

Interventions

The standard intervention was pharmacological treatment with mood stabilizers. The subjects assigned to the standard intervention followed the treatment prescribed by psychiatrists (from the public health system or the research team) according to their needs. The combined intervention consisted of medication and a short-term PE model adapted from the Psychoeducation Manual for Bipolar Disorder developed by Colom and Vieta.Citation28 The model was summarized in a protocol of six individual sessions of 1 hour each. Generally, the sessions occurred in the following order: the first introduced the therapist to the patient and explained the treatment guidelines, confidentiality issues, the PE protocol (“What is it” and “What it is not”), and the general concepts of BD (“What is mood?”). The second session explained the biological nature of BD, mania and hypomania concepts, and the social stigma related to the disease in order to modify inadequate understanding and feelings of guilt. The third session involved depressive symptoms, and the fourth instructed the patient to detect warning signs of recurrence (through the identification of prodromal behaviors) and the benefits of doing so (developing a predefined action plan with techniques and resources). The fifth session provided the patient with options of what to do when an episode was detected, emphasizing the importance of adherence to pharmacological treatment and contact with the psychiatrist, The sixth and final session summarized everything that was explained in the previous sessions, reinforcing aspects with which the patient had difficulty. The intervention was carried out by psychology undergraduates (in their final year) who were trained and supervised by a qualified and experienced researcher.

Regarding the pharmacological treatment in both groups, primarily only medication provided by the Brazilian Public Health System was prescribed, in order to facilitate the continuity of treatment after the end of the study. Lithium was the most commonly used medication, and was prescribed alone or in combination with other drugs such as anticonvulsants, antidepressants, neuroleptics, and benzodiazepines, according to the needs of each patient. There were no statistically significant differences between groups for the use of medication, combined or not.

Statistical analysis

After coding the baseline and postintervention assessment tools, data were entered twice in the Epi-Info 6.04d software (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA) with consistency checked using the validate command. After that, the data were transferred to SPSS 13.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for statistical analyses, which is presented in three tables. describes the characteristics of the sample (baseline) between the two intervention groups. The data are presented in absolute and relative frequencies for qualitative variables with chi-square tests for differences between groups. Quantitative variables are described as mean and standard deviation, since they were normally distributed in the Gaussian curve. The difference between means was verified by t-test. shows, by paired t-test, the difference between the mean and confidence interval of the difference in symptom scores and biological rhythm of the baseline and postintervention presented in the whole group, the standard intervention group, and the combined intervention group. We also present the effect sizes of each of the associations studied.

Table 1 Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of each group

Table 2 Outcome results for each group

In , linear regression was used to verify the difference between the remission scores of depressive and manic symptoms, as well the biological rhythm regulation between the proposed intervention groups. In the same table we can observe the coefficient of linear regression and the confidence interval of 95%, both crude and adjusted for economic index. The data shown refer to the combined intervention, using the standard intervention as reference. For all the statistical tests, significant associations were considered at a 95% significance level (P<0.05).

Table 3 Crude and adjusted linear regression for symptoms remission and biological rhythm regulation comparisons between intervention groups

Participants

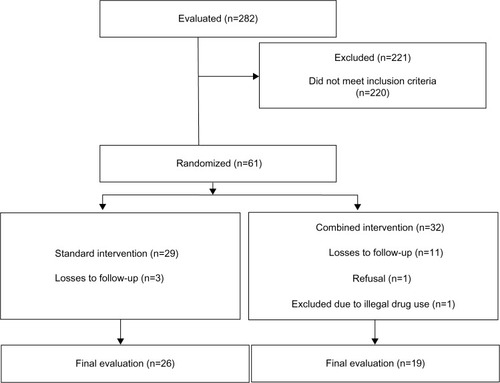

A total of 282 young adults were tested for inclusion in the trial. Among these, 220 did not meet the criteria and were referred to the Public Health System. The sample at this point consisted of 61 bipolar II subjects, 29 for standard intervention and 32 for combined intervention. During the study, there were 14 losses to follow-up (three from standard intervention and eleven from combined intervention). In addition, one patient refused to take part in the PE and another was excluded from the study due to illicit substance abuse during the PE period. Therefore, the final sample consisted of 45 individuals (26 for standard intervention and 19 for combined intervention) (). The participants were recruited between July 2010 and June 2012, and the final evaluations took place from November 2010 to September 2012.

Results

In this sample, the majority of the participants were women, with an average age of 24 years, and 12 years of schooling. Randomization was effective and the distribution was homogeneous in all respects except the economic index, which showed significant difference between groups (P=0.041). Although the groups were similar as to the presence of symptoms at baseline, the social domain (P<0.001) and the total score (P=0.040) of the BRIAN scale were different between groups. Other baseline information is described in .

Regarding the influence of the interventions on mood symptoms, according to the intention-to-treat analysis (n=61), both groups showed remission of depressive symptoms (standard P=0.006; combined P=0.041), but none showed a statistically significant reduction of manic symptoms. Unlike we expected, there was no statistically significant influence of PE on biological rhythm between the evaluations. Only the standard intervention group showed improvement in the BRIAN domains: sleep (P=0.012), activity (P<0.001), social rhythm (P=0.002) and total score (P=0.001). All significant associations presented effect sizes between moderate and strong (). There was no difference in depressive symptoms remission among intervention models after the linear regression. On the other hand, there was a tendency of manic symptoms remission in the combined intervention model after adjustment for economic index (P=0.061). However, a strong biological rhythm regulation was found in the standard intervention group (when compared to combined), regardless of the setting ().

Discussion and methodological considerations

The results showed that, in this sample and time period evaluated, the combined treatment of medication and PE had no statistically significant impact on the regulation of biological rhythm when compared to standard pharmacological treatment. As the hypothesis investigated was not confirmed, despite the methodological precision in which the study was conducted, relevant research questions emerge for future studies. The economic status, for example, which was relevant mainly in the combined intervention group, has a described negative effect on the response to PE intervention.Citation35

The sample size, a limitation of our study, reflects the struggle in finding bipolar subjects willing to enter an investigation when it was not part of a service in which they already participate. A possible reason for this is that because those subjects had only few episodes, they were not yet aware of the importance of treatment. Two other limitations of the study should be noted: the lack of control of the medication used in the standard intervention and a need for emphasis on the importance of a life routine of the subjects on the PE model. While these limitations may have influenced the study in some way, we believe, especially in the medication issue, that the success of randomization has dissipated the effects.

How PE works is worth questioning. In this particular case, when the subjects answered the questionnaires after the intervention, the PE may have helped them to become more sensitive in detecting warning signs and more self-demanding in their answers, which is common in mania and hypomania,Citation19 and consequently, lower scores were obtained. Also, the treatment duration, time period evaluated, and number of sessions probably played a key role in the results obtained. Experimental evidence shows that compact models can be effective;Citation36 however, there is a study design similar to oursCitation35 which confirms that 16 sessions (more than twice the number used in this study) did not obtain any changes. Maybe the results we obtained were not because of the number of sessions, but considering PE characteristics, that the effect happens over time and may appear in follow-up evaluations. In this sense, its longitudinal effectiveness in prophylaxis has already been proven.Citation37

Conclusion

Although the changes in biological rhythm were not statistically significant during the time period evaluated in this study, it is noteworthy that the trajectory of the score showed a trend towards improvement, which may indicate a contribution even though it may take a longer time to appear than expected. PE is an active component of successful psychosocial interventions for BD,Citation38–Citation40 but models need to be studied and adjusted pragmatically. Other strategies must be considered, such as neuropsychological rehabilitation and social skill training, in order to build a more solid treatment combination. Some interventions do not produce the expected results, perhaps due to the design chosen (possibly the topics chosen for the PE played a key role here) or to the uncontrolled variables regarding psychotherapy research. Nonetheless, we can say that PE is not only welcome in the group of psychosocial interventions offered to bipolar subjects, but is an indispensable tool in the treatment of BD.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GiglioLMMagalhãesPVKapczinskiNSWalzJCKapczinskiFFunctional impact of biological rhythm disturbance in bipolar disorderJ Psychiatr Res201044422022319758600

- KapczinskiFDiasVVKauer-Sant’AnnaMClinical implications of a staging model for bipolar disordersExpert Rev Neurother20099795796619589046

- HarveyAGTalbotLSGershonASleep disturbance in bipolar disorder across the lifespanClin Psychol (New York)200916225627722493520

- IwaseTKajimuraNUchiyamaMMutation screening of the human clock gene in circadian rhythm sleep disordersPsychiatry Res2002109212112811927136

- Malkoff-SchwartzSFrankEAndersonBPSocial rhythm disruption and stressful life events in the onset of bipolar and unipolar episodesPsychol Med20003051005101612027038

- EtainBMilhietVBellivierFLeboyerMGenetics of circadian rhythms and mood spectrum disordersEur Neuropsychopharmacol201121Suppl 4S676S68221835597

- LevensonJCNusslockRFrankELife events, sleep disturbance, and mania: an integrated modelClin Psychol Sci Pract2013202195210

- CosgroveVEAdjunctive psychotherapy for bipolar disorderFocus201149449454

- Goldner-VukovMMooreLJCupinaDBipolar disorder: from psychoeducational to existential group therapyAustralas Psychiatry2007151303417464631

- GomesBCLaferBGroup psychotherapy for bipolar disorder patientsRev Psiq Clin20073428489

- MiklowitzDJGeorgeELRichardsJASimoneauTLSuddathRLA randomized study of family-focused psychoeducation and pharmacotherapy in the outpatient management of bipolar disorderArch Gen Psychiatry200360990491212963672

- ReinaresMColomFSánchez-MorenoJImpact of caregiver group psychoeducation on the course and outcome of bipolar patients in remission: a randomized controlled trialBipolar Disord200810451151918452447

- LamDHHaywardPWatkinsERWrightKShamPRelapse prevention in patients with bipolar disorder: cognitive therapy outcome after 2 yearsAm J Psychiatry2005162232432915677598

- FrankEKupferDJThaseMETwo-year outcomes for interpersonal and social rhythm therapy in individuals with bipolar I disorderArch Gen Psychiatry2005629996100416143731

- GoodwinGMConsensus Group of the British Association for PsychopharmacologyEvidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised second edition – recommendations from the British Association for PsychopharmacologyJ Psychopharmacol200923434638819329543

- YathamLNKennedySHParikhSVCanadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013Bipolar Disord201315114423237061

- KanbaSKatoTTeraoTYamadaKCommittee for Treatment Guidelines of Mood Disorders, Japanese Society of Mood Disorders, 2012Guideline for treatment of bipolar disorder by the Japanese Society of Mood Disorders, 2012Psychiatry Clin Neurosci201367528530023773266

- PerryATarrierNMorrissRMcCarthyELimbKRandomised controlled trial of efficacy of teaching patients with bipolar disorder to identify early symptoms of relapse and obtain treatmentBMJ199931871771491539888904

- ColomFVietaEMartinez-AranAA randomized trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remissionArch Gen Psychiatry200360440240712695318

- ParikhSVZaretskyABeaulieuSA randomized controlled trial of psychoeducation or cognitive-behavioral therapy in bipolar disorder: a Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety treatments (CANMAT) study [CME]J Clin Psychiatry201273680381022795205

- HollonSDPonniahKA review of empirically supported psychological therapies for mood disorders in adultsDepress Anxiety2010271089193220830696

- MiklowitzDJAdjunctive psychotherapy for bipolar disorder: state of the evidenceAm J Psychiatry2008165111408141918794208

- ScottJColomFPsychosocial treatments for bipolar disordersPsychiatr Clin North Am200528237138415826737

- BatistaTAvon Werne BaesCJuruenaMFEfficacy of psychoeducation in bipolar patients: systematic review of randomized trialsPsychol Neurosci201143409416

- KapczinskiFVietaEAndreazzaACAllostatic load in bipolar disorder: implications for pathophysiology and treatmentNeurosci Biobehav Rev200832467569218199480

- VietaEPopovicDRosaARThe clinical implications of cognitive impairment and allostatic load in bipolar disorderEur Psychiatry2013281212922534552

- da Silva MagalhãesPVGomesFAKunzMKapczinskiFBirth-cohort and dual diagnosis effects on age-at-onset in Brazilian patients with bipolar I disorderActa Psychiatr Scand2009120649249519594482

- ColomFVietaEPsychoeducation Manual for Bipolar DisorderNew YorkThe Cambridge University Press2006

- YathamLNKauer-Sant’AnnaMBondDJLamRWTorresICourse and outcome after the first manic episode in patients with bipolar disorder: prospective 12-month data from the Systematic Treatment Optimization Program For Early Mania projectCan J Psychiatry200954210511219254441

- Del-BenCMRodriguesCRZuardiAWReliability of the Portuguese version of the structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) in a Brazilian sample of psychiatric outpatientsBraz J Med Biol Res19962912167516829222432

- BarrosAJDVictoraCGIndicador econômico para o Brasil baseado no censo demográfico de 2000 [A nationwide wealth score based on the 2000 Brazilian demographic census.]Revista de Saúde Pública2005394523529 Portuguese16113899

- MorenoRAMorenoDHEscalas de avaliação clínica em psiquiatria e psicofarmacologia: escalas de avaliação para depressão de Hamilton (HAM-D) e Montgomery-Asberg (MADRS). [Clinical evaluation scales in psychiatry and psychopharmacology: Hamilton (HAM-D) and Montgomery-Asberg (MADRS) depression scales.]Rev Psiquiatr Clín1998255117

- VilelaJACrippaJADel-BenCMLoureiroSRReliability and validity of a Portuguese version of the Young Mania Rating ScaleBraz J Med Biol Res20053891429143916138228

- GiglioLMFMagalhãesPVAndreazzaACDevelopment and use of a biological rhythm interviewJ Affect Disord20091181–316116519232743

- de Barros PellegrinelliKBde O CostaLFSilvalKIEfficacy of psychoeducation on symptomatic and functional recovery in bipolar disorderActa Psychiatr Scand2013127215315822943487

- MiklowitzDJPriceJHolmesEAFacilitated Integrated Mood Management for adults with bipolar disorderBipolar Disord201214218519722420594

- VietaEPacchiarottiIScottJSánchez-MorenoJDi MarzoSColomFEvidence-based research on the efficacy of psychologic interventions in bipolar disorders: a critical reviewCurr Psychiatry Rep20057644945516318823

- CastleDWhiteCChamberlainJGroup-based psychosocial intervention for bipolar disorder: randomised controlled trialBr J Psychiatry2010196538338820435965

- ColomFReinaresMPacchiarottiIHas number of previous episodes any effect on response to group psychoeducation in bipolar patients? A 5-year follow-up post hoc analysisActa Neuropsychiatr20102225053

- ReinaresMColomFRosaARThe impact of staging bipolar disorder on treatment outcome of family psychoeducationJ Affect Disord20101231–3818619853922